Harry S. Dent Jr.'s Blog, page 165

February 11, 2015

Government Debt: Now You See It, Now You Don’t

Ron Popeil is the late-night marketer who brought us cool things like the Veg-O-Matic and the Pocket Fisherman. He also marketed a hairspray that would help to cover bald spots.

In the commercial for that one, Mr. Popeil would walk up to people with bald spots in airports and offer to spray on some of the hairy glue. Now that was entertainment!

But it was his more mainstream product that came to mind when I read the latest McKinsey & Company report on global debt. As I flipped through the pages, I kept hearing Ron as he hawked the Showtime Rotisserie: “Just set it, and forget it!”

The gist of the report is that since the financial crisis few countries have managed to reduce their overall outstanding debt, even though there’s been widespread reduction in the amount of credit offered or used by businesses and consumers. In developed countries, there’s been some deleveraging on the private side, but this has been dwarfed by the amount of debt issued by governments.

The authors note that rising government debt can be a drag on policy and growth, so they outline possible ways of reducing the burden.

Governments could adjust their budgets (raise taxes and cut spending) so as to run surpluses which could be used to pay down their debt, or they could count on GDP to grow faster than their debt. Considering the position of most governments and their aging populations, there is little chance that either of these will occur…

Governments could restructure their debt, which is a euphemism for defaulting on some of what they owe. This is considered bad form (unless you are Greece or Argentina) and is not a likely solution.

But the report does mention one more path to decreasing government debt, although it’s not very prominent in the document. This approach calls for central banks to write off all the government debt they own. As radical as this might sound, I think the step is unnecessary.

Once a central bank buys the debt of its government, effectively the debt has already been forgiven. To paraphrase Ron Popeil, they can just set it… and forget it.

Central banks buy bonds with newly printed money. They don’t use credit or existing assets; they simply create money out of thin air and ship it to the seller of the bonds. In return, the banks receive in assets like government bonds. What happens after that is where we find the magic of debt forgiveness.

Central banks can rid themselves of assets in one of two ways — either sell the securities in the public market, or wait for fixed income products to mature. Either way, the banks end up with cash on the books.

Keep in mind that this cash came from selling securities or being paid on securities that were originally purchased with newly printed money. Once the central banks have the liquid cash in their accounts, they hand it over to their respective government treasury departments.

Reread that last sentence.

This is the step that most people find incomprehensible… when a central bank ends up with cash, it hands the money over to the government, even though the money originated by printing it out of thin air to buy securities.

This is why, from my point of view, taking the step of “forgiving” government debt that resides on the books of central banks is unnecessary. In essence, once the purchase of the bonds is complete, the whole affair from printing new money to transmitting the funds to the government is nothing but an operational sideshow.

And it doesn’t stop with government bonds. Effectively, any asset purchased by a central bank will eventually provide cash to the government, because the process remains the same — money is created, used for purchasing securities, and when those assets are disposed of, the funds are sent to the government.

The McKinsey & Company report shows that if central bank holdings of government debt were forgiven or simply not considered, then U.S. debt outstanding as a percentage of GDP would fall by 20%, whereas the Japanese government’s debt would fall by 140%.

These are not trivial amounts, but they don’t tell the whole story.

The Federal Reserve owns more than $1 trillion of mortgage-backed bonds in addition to its holdings of U.S. government bonds, and the Bank of Japan regularly buys corporate bonds and even ETFs on the Japanese stock market. When these additional assets are considered, the amount of “forgiveness” is even larger.

All of this might sound like bookkeeping mumbo jumbo, but remember one thing — when the central bank first prints a new dollar, they are effectively stealing value from everyone who currently holds dollars. This means that when the Fed creates new cash and uses it to buy anything, the theft of value happens to all of us… in that instance.

Everything else… selling the securities, remitting funds to the government, etc…. is all just noise.

It would be nice if, after stealing the money from us in the first place, the Fed would give us the money back at the end, instead of shipping it to the U.S. Treasury as a gift.

By the way… last year’s gift was a whopping $98.7 billion.

Rodney

P.S. Adam takes on another issue today… what’s fueling the commodity market. Supply or demand? Find out in today’s Ahead of the Curve.

Supply or Demand: Which Is the Culprit?

Recent morning headlines include: “Stocks are Higher and Oil is Lower.”

Which begs the question: So what the heck is an investor to do?

Commentary on the price of oil has flowed… err, gushed… since West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices peaked last summer and began spiraling lower in October. And most of the analysis you’ll read on Yahoo! Finance, and the like, is fraught with information that is flat-out confusing investors.

Last fall, I decided to wait — patiently and quietly — before making any bold predictions or recommendations in the oil/energy complex. The most I shared on the topic was in a November 4 note to Cycle 9 subscribers, in which I outlined my rationale for avoiding the sector and also urged to resist the temptation to, as I said then: “buy this falling knife.”

That ended up being a good call. Since then, oil (USO) prices have lost a further 35%. And the energy (XLE) sector was down a further 13% before bouncing a bit higher in the last two weeks.

Just yesterday, though… I told Cycle 9 subscribers that it’s time to make a play!

Energy markets are still volatile, as they seek “new normal” equilibrium prices. And while I shared last week my reasons for maintaining a bullish bias, there isn’t a crystal-clear uptrend in stocks yet. As such, it’s important to be tactically cautious in how you implement an energy sector trade.

But I’m pretty sure I’ve found the perfect way to play it.

There are two potential culprits for oil’s epic decline: excess supply or weak demand.

Of course, both factors are in play. But the brunt of the blame must be assigned to one factor or the other if we’re to figure out just how low oil prices can go… and what affect oil prices will have on other, non-crude commodity markets.

My sense is that a glut of supply is to blame.

Yes, global growth is waning. And so we aren’t guzzling quite as many gallons of gas as we were when China’s economy was growing at a rate in excess of 10% a year. But that’s a relatively long-term trend that most investors have long ago priced in.

Meanwhile, U.S. oil production has gone gangbusters in the last decade. Take a look…

Which begs the question: So what the heck is an investor to do?

Commentary on the price of oil has flowed… err, gushed… since West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices peaked last summer and began spiraling lower in October. And most of the analysis you’ll read on Yahoo! Finance, and the like, is fraught with information that is flat-out confusing investors.

Last fall, I decided to wait — patiently and quietly — before making any bold predictions or recommendations in the oil/energy complex. The most I shared on the topic was in a November 4 note to Cycle 9 subscribers, in which I outlined my rationale for avoiding the sector and also urged to resist the temptation to, as I said then: “buy this falling knife.”

That ended up being a good call. Since then, oil (USO) prices have lost a further 35%. And the energy (XLE) sector was down a further 13% before bouncing a bit higher in the last two weeks.

Just yesterday, though… I told Cycle 9 subscribers that it’s time to make a play!

Energy markets are still volatile, as they seek “new normal” equilibrium prices. And while I shared last week my reasons for maintaining a bullish bias, there isn’t a crystal-clear uptrend in stocks yet. As such, it’s important to be tactically cautious in how you implement an energy sector trade.

But I’m pretty sure I’ve found the perfect way to play it.

There are two potential culprits for oil’s epic decline: excess supply or weak demand.

Of course, both factors are in play. But the brunt of the blame must be assigned to one factor or the other if we’re to figure out just how low oil prices can go… and what affect oil prices will have on other, non-crude commodity markets.

My sense is that a glut of supply is to blame.

Yes, global growth is waning. And so we aren’t guzzling quite as many gallons of gas as we were when China’s economy was growing at a rate in excess of 10% a year. But that’s a relatively long-term trend that most investors have long ago priced in.

Meanwhile, U.S. oil production has gone gangbusters in the last decade. Take a look…

So while global demand is slowing, it isn’t slowing as much as U.S. oil production is growing. And that means there’s a glut of oil on the global market.

There’s still time to get into the trade I recommended to Cycle 9 subscribers yesterday… you can check it out here.

Best,

Adam

February 10, 2015

Bubble in the Heartland

When I give speeches and talk about the real estate bubble, a lot of people get it.

But it’s harder to argue against real estate falling, or gold, as these are more emotionally charged financial assets than stocks or other commodities that we’ve all seen rise and fall in bull and bear markets.

Real estate is an asset that is tangible, useable and rentable. Gold is intrinsically valuable and the only real money throughout most of history, along with silver.

But I keep arguing that after a debt-driven bubble, all these financial assets have been overinflated. Debt and financial asset bubbles go hand in hand throughout history… and they always burst together.

But what is more tangible than farmland?

Farmland gives the ability to grow the most fundamental commodity for human survival in an era of exponential population growth — the greatest bubble of all since the late 1700s? Down the road this has to be a good thing.

A recent study showed which investments have had the best returns adjusted for risk/volatility from 1994 to 2013: U.S. farmland, British farmland, U.S. property and U.S. forestry — in that order. The S&P 500 is next, then gold in the mid-range. International stocks and then commodities have fared the worst.

I have a friend, Doug Bell, who has raised money for farms in Uruguay with some of the most fertile soils in the western hemisphere. He sees growing population and middle-class sectors in the emerging world as putting ever more pressure on the needs for food, while farmland keeps getting eclipsed by rapid urbanization in almost all countries, especially now the emerging ones.

How can this not drive agricultural prices upward and farmland with it?

In the long term, I have to agree with that concept… but there is a short-term issue in our bubble economy that we have to examine.

When I look at the commodity price spiral downward (that we predicted many years ago), I tend to separate industrial and energy commodities from agricultural. Industrial commodities peaked on our 30-year cycle between mid-2008 and early 2011.

They continue to spiral down, likely into around the early 2020s or so, as they did from 1980 into the late 1990s before bubbling again into 2008 to 2011.

These industrial-based commodities have been crashing in recent years from oil to iron ore to copper and even the precious metals like gold. And more recently, lumber prices have been declining due to the slowdown in homebuilding trends and it’s panned out just as we expected and should continue to do so much more ahead.

But agricultural commodities have been more varied and often countercyclical. They tend to spike up more so than down — things like corn, soybeans, wheat, cattle and hogs.

In Uruguay, Doug has learned that you have to diversify with different crops and feedstock to survive the volatility in this agricultural sector.

What Will Bring the Change?A slowing global economy, which we see in spades, would generally disfavor most commodities, just the industrial much more than food. The last thing anyone cuts back on in a downturn is basic food, and of course, water.

But the emerging wild card in agriculture is climate change. Forget global warming for now. More variable climate is clearly here and is likely to continue into the future and it threatens food production as any extreme between droughts and flooding is bad for production.

Doug and I agree that the climate is likely to get colder for the next decade or more, despite CO2 levels rising for decades at unprecedented rates which have been associated with global warming.

And taking from my disciplined long-term research that is just one cycle that has been rising since the late 1700s.

Keep in mind that this is a man-made cycle. Long-term scientifically proven cycles for warming would have peaked 5,000 to 8,000 years ago at the height of the emergence of the agricultural revolution. Yet, temperatures are still high and trending toward warming in the last century. This proves that something else is going on.

However, sunspot cycles dominate intermediate-term cycles in solar radiation and rainfall and are currently declining in intensity since the late 1950s. They affect sunshine and rainfall by 20% at the top.

This is a real and proven factor for agriculture and for the global economy. These types of alternating cycles generally pointed down in intensity and did so radically from the mid-1600s to the early 1700s causing a mini-ice age.

So far, we aren’t seeing the near-zero intensity of that rare period… but the lowest levels since the early 1800s will continue to weaken in the current down cycle and are likely to continue into 2020 at a minimum and likely into 2030 or longer.

That means more restrictions on agricultural production, especially in colder, more affluent areas as global population continues to march forward toward a peak in 2060 to 2100 at 9 to 10 billion!

But here’s my short-term problem with farmland prices:

A global downturn will only put some downward pressure on food prices, although it is less than on industrial commodities.Farmland has seen its own extreme bubble since around 2002 (on a lag to home prices) as the next chart shows in the Midwest in the U.S.It’s mind-blowing.

In Iowa, it’s gone up 7.7 times since 1990 and 4.6 times since 2000. In Indiana, it’s up 12.3 times since 1987 and in Illinois it’s seen an increase of 6.8 times since 1987.

This bubble that has been driven, like all bubbles, by super cheap money and speculation!

I see this bubble bursting in the next few years just like all the rest of the debt bubbles and speculation unwind around the world.

However, I’d rather own farmland over much higher-priced urban land if I had to make a choice.

By the early 2020s, a global boom dominated once again by emerging countries will accelerate demand for agriculture (and industrial commodities) more than ever. Then a few decades down the road, rising pollution, CO2 and methane levels — which are cumulative in nature and don’t dissipate for a long time — will likely cause another period of warming again, but beyond most of our lifetimes.

Both cooling in the next few decades and warming over the next century will cause havoc and continued unprecedented climate change over the rest of our lifetimes. That will likely make agricultural commodities the most interesting sector for investments in the long term.

The farmland bubble will very likely burst in the next several years, and more in developed countries with limited land than in emerging countries. Couple that with cooling trends against expectations and agricultural commodities could end up seeing the greatest bubble from the early 2020s forward, along with industrial commodities and gold again.

Farmland around the world, like India and emerging country stocks, are likely to be the best long-term investments after the next great crash and deflation cycle — and likely well ahead of the bottom in industrial commodities due more in the early 2020s — possibly in the next year or two. Get hip on both and do your research because the knowledge you gain will be an asset.

For our March issue of Boom & Bust, I’m looking at giving you an illuminating and more in-depth analysis of climate cycles from a more hierarchical and proven approach.

You’ll have a clearer view of climate cycles than most scientific experts! If you want to dig deeper, consider subscribing to Boom & Bust.

I agree with most scientists on climate change longer term, but like Doug Bell, I believe that over the next few decades a critical shift will continue. Cooling is the trend ahead, not warming.

What an opportunity if you see it coming!

Harry

P.S. Lance explores the ongoing bond bubble in today’s Ahead of the Curve. Read up on it because we all know what happens to bubbles!

The Fed and Bonds

Harry Dent has extensively researched cycles in stocks, real estate, business, politics and even sunspots! He mentioned that cycles that drive debt higher, like the one we’re in now, tend to overinflate all financial assets. These types of bubbles are more likely to pop simultaneously.

Like the real estate bubble Harry predicted 20 years ago that has since burst, we seem to exist in a “bubble economy.” The most recent real estate bubble burst in 2006 is now reinflating. The commodity bubble is in the process of popping with oil prices down more than 50% in a few short months. And the stock market is in a bubble that is seemingly “unpoppable.”

I’ve been keeping my eye on another bubble that seems to be getting out of control… interest rates. More specifically, U.S. Treasury bond prices. We don’t usually think of dropping interest rates as a bubble but when rates drop, prices go up and do so because investors see too much risk elsewhere or a future economic outlook that is bleak.

There are many factors that influence the price of bonds — one being policy decisions by the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed). The fact that the Fed only sets the interest rate policy in the Federal Funds Rate or the Interbank borrowing rate, affects rates all the way out the yield curve (short- to long-term).

In a healthy, growing economy, yields go up the further out over time. When the yield curve gets flat, the interest rates paid to long-term investors (30-year bond) is not much more than is paid to short-term investors (2-year note).

The long-term investor assume more risk the longer the duration of investment. Why would anyone risk more for less? A couple weeks ago I wrote about U.S. bond yields compared to others around the world and our rates are competitive, to say the least!

U.S. bonds are regarded as the safest so the demand remains high.

Why do I believe there is a bond bubble? The yield on the 30-year bond is down 35% in the last year while prices are up more than 25% on actual bonds. The Dow is up just under 12% in that time and the S&P 500 is up about 14%.

I’m not going to speculate as to what could be the trigger that causes the bond bubble to pop but the Fed has done much to create the bond bubble (among others) and the Fed could ultimately crash the market. The primary reasons behind the current false sense of stability have been keeping rates artificially low and feeding the markets liquidity with quantitative easing (QE).

The Fed’s credibility in adhering to its congressional mandates could fuel the fire. They are mandated to “promote maximum employment, production and price stability” and seem to have done a wonderful job of stabilizing and increasing stock prices.

On the other hand, they’ve done little to maximize employment wage growth. Consumer prices have increased unevenly as a result of the Fed tinkering over the last six years but wage growth has not followed.

The Fed has indicated their intentions to start raising interest rates sometime after the April FOMC meeting but investors don’t believe it and are still buying U.S. Treasurys. Many market observers (including Harry Dent) believe it’s more likely the Fed will re-engage in QE rather than raising rates.

Either way, I believe the Fed is backed into a corner and either move could be disastrous. If the markets believe the Fed has completely lost credibility, look out!

Lance

February 9, 2015

The Currency That Would Be King

Dollar haters have a new love.

It’s a currency that’s been a dark horse contender in the race to replace the greenback for years now, and according to some analysts it recently surged ahead to become the most likely challenger.

The latest data point supporting this argument is the country-in-question’s growing role in the world of global payments. The use of the currency in global payments has increased substantially over the past two years. However, the percentage change — up 266% — masks the distance between it and the leaders.

Sure, it has moved from No. 13, where it accounted for 0.6% of global payments as measured by the Bank for International Settlements, to fifth, where 2.2% of payments were made with the currency. But at the end of 2014, 40.2% of global payments were in euros while 33.5% of payments were in U.S. dollars.

To catch these two front-runners, use of this dark horse would have to increase by 1,827.3% or 1,522.7%, respectively.

That’s not likely to happen anytime soon, and chances are that its issuing government doesn’t want this to occur anyway.

Of course I’m talking about the yuan.

If demand for it suddenly ballooned, it would kill the Chinese economy, not help it grow.

According to World Bank, exports comprised 26.40% of Chinese GDP in 2013, which is just a fraction less than the 26.72% of GDP attributed to exports five years ago. While Chinese government officials have made a lot of noise about weaning the country off of its addiction to exports, the reality is that selling stuff to other countries remains very important. A rising demand for yuan would dent trade.

When demand for a currency increases, the value of the currency also goes up. This is great for consumers who live in the country with the rising currency because they can now buy foreign goods at a cheaper price. Unfortunately, businesses in the country with the stronger currency now sell less of their goods to other countries, since their goods cost more when priced in other currencies.

This double-edged sword makes the issue of a strong or weak currency something of a political hot potato. And it’s the basic debate going on in central banks around the world today… but it takes on special meaning in China, where the government pegs its currency to the U.S. dollar.

Pegging ItIn an effort to stabilize its exchange rate, everyday China sets the official rate at which yuan can be traded for dollars. However, in a nod to changing conditions, the yuan is allowed to fluctuate within a 2% band around the official exchange rate.

This combination of a peg and a floating rate is meant to allow market forces to work, but not go overboard. The Chinese allow flexibility, but only on their terms. And that takes us back to the issue of a rising currency.

If Chinese leaders wanted more global payments to be made in yuan, then they would have to make yuan more available to foreign entities. Rising demand for Chinese currency on the world markets would lead to upward pressure on the exchange rate for yuan, which the Chinese government controls.

If the government kept the yuan artificially low to assist Chinese exports, then the country would face the charge of being a currency manipulator, which carries penalties from the World Trade Organization. If the value of the yuan were to rise, then exports, which account for a quarter of GDP, would be hurt.

To make matters worse, once sufficient amounts of yuan were available away from China, more of the currency would trade outside of the government’s control. Offshore yuan trading already occurs. In this unpegged environment, the yuan is free to move against other currencies based on market conditions without constraints.

If offshore trading overshadowed mainland trading, the Chinese government would lose control over the exchange rate, and thereby lose the ability to set one of the most important components of its very large export business.

So while the Chinese might rail against the U.S. dollar from time to time, and might even talk about how the yuan should occupy a more prestigious place among world currencies, it makes little sense for a country that uses a command economy to turn control of its currency over to international forces.

In other words, don’t buy into the “end of the dollar” arguments you hear from time to time. For better or worse, the dollar’s status as the reserve currency appears to be safe for years to come.

Rodney

P.S.

Charles talks about an interesting demographic trend in China that will have a significant impact. Keep reading…

China’s Baby Bust

Shifting gears from money to love, here’s a little something to think about with Valentine’s Day on Saturday…

Chinese couples will be making a lot fewer babies in the years ahead.

And this has major implications for the country’s future growth.

A baby bust might sound counterintuitive to anyone who follows China. After all, the government announced in 2013 that it would be relaxing its One Child Policy. Most China watchers assumed this would lead to a Chinese baby boom. But they’re ignoring the large demographic elephant in the room: babies require mothers. And after three decades of the One Child Policy, China is about to have a major shortage on that front.

Take a look at the chart below. It forecasts the population of Chinese women by age using demographic data from the United Nations.

As you can see, China’s population of women of prime childbearing age (25 to 29) goes into steep decline this year and doesn’t significantly recover… ever.

Average age of marriage and first childbirth are rising worldwide, and as a general rule the more developed a country becomes, and the more educated its women become, the higher the age the women get married and have their first child.

So let’s assume that China’s women, like many Western women, are postponing motherhood until their early 30s. Even then, China has a major problem. Its population of women aged 30 to 34 goes into steep decline starting in 2020.

Conception is still possible into the late 30s and 40s, of course. But it gets far more difficult and, realistically, it limits family size. You can’t have a large family if you’re getting started in your late 30s. And in any event, the population of women aged 35 to 39 goes into steep decline 10 years from now as well.

Let’s say that Chinese women, aided by new technology, somehow rewrite the laws of human anatomy and make large families possible into early middle age. Even then, China has a major problem: the country has evolved with small families as the norm and costs have risen accordingly.

Living costs have risen in the cities to the point that large families aren’t economically viable for the vast majority of Chinese households, and urban apartments are not big enough to accommodate them.

This is a major problem for China and for any Western company that has made large investments in Chinese growth. Children are the future. You need them to pay the taxes and man the factories of tomorrow.

More critically, in the age of modern consumer capitalism, you need them swiping the credit cards and buying the homes of tomorrow. This is particularly critical for China given its government’s stated goal of reorienting its economy away from exports and toward domestic consumption.

Is mass immigration of young women the answer? Well, that sounds good, at least to the red-blooded young men in the room. But the math doesn’t quite work out. China’s population of 20- to 24-year-old women shrinks by about 30 million over the next 10 years.

Where, exactly, would China find 30 million blushing brides willing to immigrate?

To put that number in perspective, that’s bigger than the entire female population of South Korea, including everyone from newborn baby girls to elderly women.

Let’s just say that Chinese wedding planners and pediatricians are looking at lean times ahead.

Charles

February 6, 2015

Precision Biotech: New Developments in Human Genome Sequencing

President Obama released his 2016 budget on Monday, and much to both the Republicans’ and Democrats’ pleasure, he’s allocated $215 million to his “Precision Medicine Initiative.”

Bipartisan support?!

Sounds impossible, I know. But it’s true. Both Republicans and Democrats see value in the initiative because it’s designed to provide physicians better tools to diagnose and treat patients. Ultimately this will save more lives while also saving health care costs…. making everyone happy.

And this couldn’t happen fast enough.

Despite all the advances in modern medicine, the health care community still wastes billions of dollars by running patients through “one-size-fits-all” diagnosis and treatment approaches (never mind the other huge issues making the industry a nightmare that patients must stumble through, as Rodney explained yesterday).

Precision medicine takes a different approach. It first accounts for differences in each patient’s genes, environment, and lifestyle. Then it custom tailors medicine to a patient’s genome (sum of all of your DNA), resulting in more effective treatments. This is stuff right out of science fiction books. It’s never been done before.

But why not?

Quite simply: this form of disruptive technology was not economical until now, like farmers not having the resources to leverage machines before the industrial revolution. Thankfully, we’re now going through another society- and life-changing revolution in supercomputing, machine learning, and biotechnology hardware.

Thanks to advances in technology, the cost of sequencing a single human genome has fallen from $100 million in 2001 to about $1,000 today, and will probably cost as much as a simple blood test by 2020.

This advanced analysis capability, combined with the fact that we’re all turning into big walking sensors with our smart phones, smart watches, and fitness trackers, gives the medical community a custom tailored, real-time diagnosis and treatment reporting capability like never before.

In turn, that gives us opportunities to invest in and profit from such amazing developments. And that’s what I do for my Biotech Intel Trader subscribers. I follow the industry trends and advancements (and yes, even setbacks) and then I give readers specific trade details so they can take advantage.

You should give it a try. But before you do, look out for my Ahead of the Curve article next Friday. I’ll show you what will happen next in the precision medicine initiative and how I can use that to help you make profitable investments.

Ben

A Message to Central Banks: Let the Economy Run Its Course!

OK, so you know that I don’t think governments should go too far to counter the natural cycles of the economy.

Those cycles have their own innate logic as they meander toward creating greater innovations, income and wealth. Markets and economies need the polar opposite of boom and bust, inflation and deflation, innovation and creative destruction.

When governments go too far trying to counter those realities, they end up doing more harm than good. They can’t accept that growth isn’t possible without pain, so they do everything in their power to keep the hurt at bay. Only, doing that simply prolongs the inevitable… and always makes the outcome worse than if they’d just let the free market run its course.

And you know that I think government and central banks the world over have gone too far in their efforts to fight the natural winter season our economy is embroiled in until 2023. They’ve created more than $10 trillion — $3.5 trillion in the U.S. alone — out of thin air, all in the vain and delusional attempt to keep the tide at bay and the bubble going!

That’s just crazy.

Unfortunately, it gets crazier still… and this next part really makes me mad…

All of that money “created” has gone straight to financial institutions, where it’s been used to speculate and create an even greater bubble in debt and financial assets, and that only works to the advantage of the ultra-rich! I’m talking about the top 10% to 0.1%-plus here.

And we have special interest groups and lobbying in the areas of health care, military financial and education (in that order) to thank for that. They drive our political system. “Save the big banks, save AIG, save GM,” they chant.

But why not save the average household that has been suffering from one financial blow after another since 2000. Real wages have declined by more than 10% since then. Many are still living in homes that have less value than what they owe on the mortgage. Their standard of living hasn’t improved one iota, even with all the stimulus central banks have pumped into the system.

I think quantitative easing was the biggest mistake central banks could have made. Not only has it created yet another bubble that will crush millions more people when it bursts ahead, but such programs have done nothing to help the average household and even less to solve the underlying problems.

What those in charge should have done is actively work to restructure the massive debt build-up in the private sector, which outweighed government debt by three times at the crescendo of the bubble in 2008.

They could have done this through a collective Chapter 11 debt restructure, requiring banks to write down loans to fair value, while giving liquidity to the banks to avert a total meltdown. That $3.5 trillion could have gone into orchestrating as much as a $22 trillion write down in the 2000 U.S. bubble debt!

That would have helped the average citizen and the small or medium-sized businesses as much of their debt would have been written down.

Or… they could have just sent a check to every household (proportionate to the number of people in the house, of course). With that $3.5 trillion newly “printed” money, each household could have received about $30,000 each.

That would have stimulated demand where it could be of most value to the economy and have tilted the gains to the middle class, not the 1%.

But no! The foxes were brought into fix the henhouse and now we face possibly the biggest economic and market crisis in the last 90 years!

And with every day that passes, we hear new warnings and see new triggers that could be the one to bring the whole damn thing down.

There’s falling inflation and commodity prices, despite unprecedented stimulus.

China is slowing, even after the greatest over-stimulated government-driven bubble in history.

Southern Europe and Germany are being lead downhill by declining demographic trends.

Terror is growing around the globe, as expected when we consider the current Geopolitical cycle.

And falling oil prices have and will continue to burst the fracking bubble that developed over the last six years of QE.

All it will take is just one of those things to break the camel’s back… to be the last grain of sand that starts the avalanche.

Sadly, there’s nothing we can do about the missed opportunities. There’s nothing we can do to prevent central banks and governments from continuing to make foolish and damaging decisions.

What we can do is be prepared. As those citizens who didn’t see the benefits of all of the stimulus money, we can now put ourselves in a position where we can improve our financial situation… or, at the very least, prevent it from getting worse.

All it takes is the right research… powerful, reality-based insights, and a plan of action, all of which we aim to provide you daily, weekly and monthly.

Get ready.

Harry

Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr

February 5, 2015

The Health Care Scam Continues

$51,720.77.

That’s how much my health insurance company boasted I’d saved through their efforts in 2014. Right.

According to my Health Statement, my medical bills totaled $66,564.88 last year. However, my incredible, superhero health insurance company swooped in and rescued me from such high costs by “negotiating” my expenses down to a manageable $14,844.11.

Seriously? Who believes this sort of fiction?

If the actual “cost” of medical care for my family last year — which involved two minor outpatient surgeries — was anywhere close to $66,000, then the medical providers would go broke by accepting a measly $14,800.

The fact that the medical providers agreed to the significantly lower compensation means that they’re still profitable at that level. The $66,000 figure is nothing more than a fantasy number that no one pays, but health care providers and insurance companies hang their hats on to make it look like they’re actually working for consumers.

When I do the math on actual dollars and cents, it shows that my insurance company is still rolling in profits.

As I said, my insurance company shows that it squeezed my health care providers until they agreed to accept more than $50,000 less than what they billed. What is not clearly spelled out is that, of the $14,844.11 of allowable costs, $2,227.40 came from me in the form of deductibles. The insurance company only forked over $12,616.71.

That might seem like a hefty sum, but I paid $20,148 in premiums last year, which means the insurance company made a gross profit of $7,531.29 off of my account alone. That’s more than 37%.

What did I get in return for this fabulous contribution to the well-being of my insurance company?

A premium increase!

To keep my stellar policy that “saved” me 78% of the billed cost of care, I was informed that I would have to increase my monthly payments by 23%. I guess a gross margin of only 37% was just too thin of a spread for them. They had no choice, really. My premiums just had to go up to keep the whole enterprise afloat!

When I received the premium notice last year, I did what anyone would do. I went shopping. Using the handy HealthCare.gov website, I found a policy that would fit my needs and would cost a little less than my old policy. Granted, I was moving down from a “gold” plan to a “silver” plan, but that seemed OK.

Only, it wasn’t OK, which is something I didn’t find out until I went to the doctor.

In early January, I went to my family physician and proudly handed them my new insurance card. They proudly handed it right back and said: “We don’t accept this one.”

I was dumbfounded.

It was the same company as my old plan, and still the same type of plan (PPO), it just had different co-pays and deductibles. I explained to the administrator that I checked for my doctor on their website before I accepted the plan. She told me that while they do accept many PPO’s from that insurance company, they don’t accept my new one.

Fabulous.

By happenstance, my insurance company has a physical location in town, so I drove straight from the doctor’s office to their office. The service representative asked what I needed. I explained that I needed a plan that covered my doctor and I showed her my new card. She looked at it and said: “Oh, yeah, that’s a great plan! But it doesn’t have many doctors in it.”

As a client who’d spent time on HealthCare.gov, time in the insurance company’s office, and time at my doctor’s office where I couldn’t see the doctor, I failed to see how this was a “great plan.”

Unfortunately, this story has no end. I switched around some coverage and, since it was still within the enrollment period, I was able to set up a different plan. But that meant canceling the existing plan that had been in effect for five days, and verifying cancellation of the plan from 2014, as well as paying for and securing the new plan.

If this sounds confusing to you, imagine how it sounds when I explain it for the fifth time to yet another representative on the phone because the insurance company can’t get it right.

All of this makes me wonder: “What do regular people do?” When I say “regular,” I mean people who don’t have a flexible schedule like I do, so they can’t choose to spend 90 minutes on the phone arguing with customer service, or can’t shoot over to the local insurance office in the middle of the day, and don’t have the time to peruse HealthCare.gov and other sites collecting information.

Can regular people be expected to jump through all of these hoops and fight with their insurance providers to drive down costs? Is it likely they will even try, or just simply roll their existing plan to the new year and hope for the best?

The entire industry is filled with incentives that drive everyone to crazy extremes.

Doctors are motivated to slice their care into smaller and smaller pieces, where something as simple as a shot is billed as the supplies (syringe, needle, gauze, etc.), the medicine, and the act of the injection. While they’re at it, why not charge for the “prep,” which would be swabbing the area with alcohol, and “post-injection services,” where they could charge for the Band-Aid as well as the act of affixing it to your arm?

Meanwhile, physician groups are encouraged to jack up the list price of everything so that their negotiated rates look better, even though the entire planet knows that the list prices are meaningless.

The problems I’ve highlighted here weren’t caused by the Affordable Care Act, but they weren’t solved by it either.

By subsidizing care for many millions of people, we’ve just added more customers to an industry that was already dysfunctional. We keep working on the cost of the outcomes (patients paying for care) without addressing the cost of the care in the first place.

This is just like another system we keep addressing backward: student loan debt. Instead of focusing on lowering the cost of college (as Harry talked about yesterday), we keep trying to find ways to ease the pain of loan payments.

Until we strip away all of the crazy things that go into pricing in the health care industry, we’ll never get a true reckoning of the costs of care. Without that, we won’t be able to make sensible changes before the boomers crowd the door at the doctor’s office complaining of all the ailments that hit when you’re in your 60s or 70s. If we don’t fix our system before then, there’s no telling how expensive the cure will be.

Rodney

P.S. Sticking with a discussion of headwinds buffeting us, you’re going to want to read what John has to say…

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

Ahead of the Curve with John Del Vecchio 3 Gales Ripping Across the Market Will Hit U.S. Companies3 Gales Ripping Across the Market Will Hit U.S. Companies

Aside from the health care headwinds that Rodney was telling you about, there are three gales blowing in the markets in particular. Each one is making it increasingly difficult to expand the market’s price/earnings multiple and drive the major indices to fresh all-time highs. As a result, I think things are getting riskier by the minute, so be careful about how much new capital you invest right now.

The first gale is a strong U.S. dollar, which is pressuring companies with a large portion of foreign revenues. We’ve seen bellwethers as diverse as Caterpillar and Microsoft warn investors that a strong dollar has crimped their opportunities overseas. Their comments led to an intra-day swoon of more than 340 points in the Dow Jones on January 28.

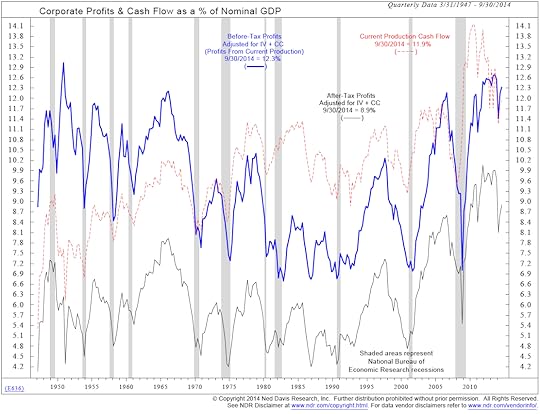

The second gale of concern is corporate profit margins and cash flows. They’re at 50-year highs. As such, it will be increasingly hard to move the needle much more. Companies have already cut a lot of costs of operations through layoffs, consolidations, and reducing excess capacity so there’s no wiggle room left.

The third gale is mean reversion. History shows that profit margins always revert to the mean. This makes perfect sense in the real world while the Wall Street casino struggles with the idea.

Wall Street analysts get seduced into extrapolating trends that simply cannot continue, but Main Street operates from a more rational set of rules. If margins are too high and unsustainable, competition can enter the space, undercut the price, and grab market share.

At 12.3%, profit margins are in nosebleed territory. They aren’t going to 14%.

Take a look at this chart…

No, it’s not a heart rate monitor, but a closer examination will certainly get your blood pressure spiking.

The line I want you to pay attention to is the thick blue one. At 12.3%, profit margins are at a level last seen around 1965. The high for the entire period going back to the late 1940s is about 13%. So, unless “it’s different this time” and economic principles are going to be tossed aside, we’re pretty much at the top.

I assure you: it’s never different “this time.”

Price/earnings expansion through an improvement in profit margins is virtually impossible from here.

There’s another important point to note from that chart. The shaded vertical areas represent recessions. See just how quickly margins come crashing to earth?

Events between 2000 and 2008 should be fresh in our minds. But, the prior recessions in the 1980s and 1990s saw significant margin contracts as well. Margins, like stock prices, tend to overshoot. The higher the climb on the upside, the greater they fall when the tide turns.

So be cautious with your large-cap holdings and tighten stops. Also, be slow to allocate fresh funds to large caps that are at historically high valuations.

And be ready to short small-cap stocks before it’s apparent that a bear market has started. I’ll alert you to the excellent opportunities out there when the time comes.

John