Harry S. Dent Jr.'s Blog, page 164

February 19, 2015

Retirement Planning: How Much Money Do We Really Need?

I want to win the lottery. As I write this, the Powerball lottery is at $450 million. The cash value option is $304 million. I know the odds aren’t exactly in my favor, but if I win, I’ll rest easy that I can retire in comfort.

Short of winning the lottery or some similar event, I worry about having enough money to last the rest of my life. Even though I save and invest, and I have many years before I check out of the workforce, I’m still concerned.

I think most people share this worry.

A few years ago a popular book, The Number, set about finding the answer to the question of how much we need to retire, but it never really solved the puzzle. Like so many financial advisors (who are good at their jobs, don’t get me wrong), books on this subject start by asking consumers to outline their anticipated expenses in retirement, as well as their assets.

Then it becomes a game of math.

If you invest for X years and earn Y% return, then you’ll have Z amount to meet your expected obligations. But what if I can’t work for all of X years, or my return falls short of Y%? Then Z is sure to suffer.

At some point we all realize that if we do this wrong and end up short of funds, then our quality of life in retirement will go down the drain. By that time we’re past our working years, so there’s not much we can do about it. We don’t get a second chance to build our retirement savings.

Those are scary thoughts, indeed.

Think about the craziness of preparing for retirement. We are told to put away enough money so that it can grow to meet our needs. OK, so start with an easy question like, “How long will we be in retirement?” No one knows (hopefully!), so we have to guess.

How much will we earn on our investments? Again, no one knows. The long-run average return on large-cap stocks is about 9%, but the actual return in any given year can be wildly different. And don’t forget that once we reach retirement, we have to decide the rate at which we take money from our accounts, which is another guess.

With something as important as the quality of our lives during our retirement years hanging in the balance, we have to guess at major components of our planning – the time frame, the returns, and the rate of distribution. Somehow this doesn’t give me a warm fuzzy feeling.

The anxiety I feel, which is shared by so many, is leading to some interesting outcomes. Robert Shiller wrote in the New York Times that this anxiety is driving investors to chase assets, buying them at almost any price simply to have their money invested. Fearful of losing the value of time in the markets, we rush to buy stocks and bonds that have already moved up in price. Shiller’s point is that, through our anxiety, we drive asset prices to lofty levels.

These same concerns could lead us to consume less and save more, which only makes matters worse by increasing the amount of cash chasing investments.

This all might be true, but what’s the alternative? We know Social Security won’t meet our needs, and there aren’t many parents just rushing to move in with their adult kids.

As I started thinking about this the other day it struck me that what many of us crave is the defined benefit plan that so many of our parents enjoyed. We want guaranteed income for the rest of our lives with no hassles and no worries. We want to put the risk of investment loss or tortured planning over time horizons onto someone else.

With that in mind, I went looking in the area that I figured had already solved the issue – annuities. Sure enough, something like this exists.

Before you roll your eyes or click away, understand that I’m not pushing anything here; I’m just noting what I found. And nothing is without drawbacks.

The classification I came across was deferred immediate annuities, or DIA’s. These contracts allow consumers to pay a premium today and defer starting their guaranteed payments until sometime in the future. I called my friend Terry Reid who works with MassMutual for more details.

She told me their product allows the investor to put down $10,000 and choose any time from just over a year to 40 years in the future to begin receiving payments. In between the initial investment and starting the payments (but not less than 13 months before payments begin), investors can kick in more money in increments of $500.

There are many variations on this basic structure, but they all come with risks.

The money is not accessible before the payment stream begins. Unlike my portfolio of stocks and bonds, I can’t access these funds if the need arises. Also, the guaranteed payments are only as good as the company behind them. What if something happens to the insurance company?

At the end of the day, it all comes back to the same thing — there is no simple solution to preparing for retirement. The workbooks and quizzes that help us estimate expenses have their place, as do stock and bond portfolios, but we shouldn’t overlook some less traditional avenues like DIA’s , which can provide stability and continuity in a world filled with uncertainty.

The answer to the question of “How much do I need?” is simple: more than I have today. And I need it spread among different types of investments and opportunities, so that if any one thing fails, it doesn’t sink the whole ship.

Unless I win the lottery… then it’s all T-bills and tequila!

Rodney

February 18, 2015

Systematic Investing: Strategy Versus Tactics

You’ll probably laugh at me… but on Monday, while most people enjoyed a day off from work, I got engrossed in a book about value investing through a “systematic” lens.

Systematic investing is often misunderstood.

By whatever name — quantitative, algorithmic, non-discretionary or rules-based — the idea of systematic investing sometimes conjures images of “black box” computer programs driven only by electrical impulses… instead of fundamentally robust investment philosophies.

But that’s a misnomer. Computers, databases and statistically sound algorithms can only refine the discovery and implementation of a fundamentally sound investment strategy. At the end of the day, computer algorithms or not, you still need a rock-solid investment strategy.

Case in point is the book I was reading…

Basically, the author was using time-honored value investing strategies – those preached and practiced by none other than Warren Buffett and Benjamin Graham – with systematic, rules-based implementation.

To use a war analogy, value investing was the strategy, while a mechanical rules-based system was the tactic. Taken together, the approach showed its ability to outperform passive index investing over the course of many decades and through various market conditions (i.e. bull markets and bear markets alike).

The point is, it wasn’t some esoteric and complex algorithm that allowed for market-beating returns… it was a fundamentally sound investment strategy: “value.”

The “systematic” implementation only contributed additional, icing-on-the-cake type of benefits, namely efficiency of data processing and mechanisms that prevent emotions-driven decision-making.

More so than ever, I believe that a rules-based approach to investing is a must-have for any serious go-it-alone investor. And, of course, that’s exactly what I aim to provide in Cycle 9 Alert.

Adam

Are Central Banks Killing The Golden Goose?

Are central banks a good thing, or a bad thing? The truth is both!

Let’s go back in history to see the truth about this matter.

The Industrial Revolution was clearly led by Great Britain from the late 1700s. That country industrialized faster and urbanized first before all other nations.

It was a highly innovative island country (centuries later, Japan would follow in their footsteps) and it had high resources of coal and iron ore — the key raw material for the up-and-coming industrial revolution that was accelerated by the steam engine.

But it also saw major innovations in agriculture. That forward movement freed up its workforce and made it possible to expand into the industry due to the higher productivity in farming. It was the advent of things like the four-crop system of rotation; radically better seeding development and techniques, as well as major improvements in animal breeding.

But there was more to Britain’s early success that made them the greatest and most powerful nation going into World War I… they developed the financial infrastructures needed for massive investment and urbanization.

In 1601, England established maritime insurance (later evolving into Lloyd’s of London) and not a century later, they created the London Stock Exchange in 1698. Limited liability corporations emerged to make investment less risky. But there was something else…

The Bank of England was chartered in 1694. It was to be the banker’s banker, like the Federal Reserve of today.

It became the byword for safety and stability in Europe. This allowed for a great market for its bonds so that capital was easier and more efficient to raise at lower rates. It was yet, another advantage for the capitalistic and industrial revolution that was just ahead.

During the same time frame, John Law brought the first central bank to France. But this major advantage soon turned into a secret flaw.

Both central banks not only used their power to lower short-term volatility in interest rates and economic cycles – as the Fed does today – but they created greater volatility down the road by manipulating their economies and not allowing shorter-term resets in the boom and bust and inflation/deflation cycles.

Even worse, France and England had massive debts from decades of war between the two countries. The Bank of England chose to market the South Sea Company to investors to raise money to pay off those debts.

John Law in France chose to market some newly acquired swamp land in the Mississippi territory to investors in order to raise money… both at attractive prices and low government-guaranteed interest rates to finance.

These first central banks financed speculation at low government-backed interest rates loans from money created out of thin air! Does that sound familiar?

What was the result? It was the first great stock crash in modern history from 1720 to 1722 in the chart below from the South Sea Bubble in England.

Since this was the first major stock bubble, it was most extreme, as investors had never experienced such a thing! Not since the great tulip bubble that came about in a narrower scheme in the mid-1600s.

Stocks didn’t recover from this bubble and didn’t begin climbing up again until the late 1780s – a 67-year bear market – and it happened just as the first efficient steam engine hit and the great Industrial Revolution took off, led by Great Britain, followed by France and the rest of Western Europe.

The Fed was chartered in 1913 in order to combat the volatility in the economy and in the interest rates. This move led to a lessening in volatility until the early 1920s and 1930s when two great deflationary bubbles burst and the subsequent crashes occurred.

The lessons here can be brought up in two points:

Central banks almost always increase longer-term volatility, as they tend to stimulate so they can counter downturns. This move prevents the natural rebalancing in the short-term picture. This only creates greater imbalances from the debt and financial asset bubbles that lead to even greater depressions and financial crises when things finally go wrong… i.e., the 1720s, 1930s and the one on our horizon.Central banks are necessary to provide credibility for any nation and its currency. It allows for the necessary short-term liquidity in financial crises and brings much-needed confidence and… an even greater stability, just as Great Britain first demonstrated.The key to all of this is central bank policy that promotes point No. 2 above and not No. 1.

Today, central banks are, more than any time in history, preventing the natural cycles and rebalancing of the free market system, while simultaneously eroding the confidence that they’re supposed to provide for stability and short-term liquidity.

When a crisis first sets in, it’s OK to flood the economy with free money for a short period of time… it keeps it under control. And you don’t get the kind of crisis that makes a mountain out of a molehill, right?

On the other hand, it’s not OK to have an endless policy of printing such a colossal amount of free money that it only creates profitable and irresponsible speculation versus productive investment. It also prevents the restructuring of debt and financial asset prices for future prosperity again – and a much needed and necessary great reset!

This is what I call “killing the golden goose” and David Stockman calls it “the corruption of capitalism.”

There is no way that six years of unprecedented money printing will work out well. In fact, it can only end in an even greater depression and financial crisis… so be forewarned!

Harry

P.S. Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr.

February 17, 2015

Too Big To Fail? Big Banks Up to Old Tricks

Big U.S. banks are hopping mad that they might suffer more than their European brethren under capital rules. The problem is that the new rules were written in Europe and the currency chosen for judging compliance is the euro.

The strong U.S. dollar makes U.S.-based bank activities look much bigger when they’re converted to the cheaper euro, so the U.S.-based banks would be required to hold more capital in reserve. The more capital these companies are required to hold in reserve, the less that can be used for investing or other financing activities.

Cry me a river.

I’ve little sympathy for the people that run these “banks.” They are companies like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. The names should conjure up some vague memories of how these venerable Wall Street firms came to be known as “banks” in the first place.

They were bailed out by the Fed when the financial system imploded…

The causes of the financial crisis have been beaten to death. I’ve no interest in rehashing subprime, the Community Reinvestment Act, or the ratings agencies. But… there is one piece that often gets left out of such discussions — the Merrill Exemption of 2004.

In the early 2000s, the big investment houses were annoyed that they were required to hold so much capital in reserve. While Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers and other American companies could only borrow at a leverage of 12-to-1, their counterparts in Europe regularly borrowed at 20-to-1 or more.

Since the competitors across the pond could put more money to work, they clearly enjoyed a competitive advantage. The investment banks petitioned their governing agency, the SEC, to change the ruling and therefore level the playing field with the Europeans.

In 2004, the SEC caved and provided what was called the “Merrill Exemption.” Investment banks with $5 billion or more in capital were basically allowed to police themselves, coming up with their own guidelines for risk control.

It’s not surprising that the companies in this category felt 12-to-1 leverage was way too conservative, so they levered up. And therein lies the problem. These companies were allowed to use whatever leverage they saw fit, which proved disastrous.

By the time it failed, Lehman Brothers had a leverage ratio of 35-to-1. For every $1 of capital, the company had invested $35. So if Lehman lost more than 2.86% of its capital, the company would be doomed. At the original 12-to-1 funding ratio, Lehman would have had to lose more than 8.33% of its capital before it got into trouble.

While Lehman was allowed to go into bankruptcy, the other investment banks were not. The only problem was that the Fed had no authority to “rescue” or lend to investment banks that were regulated by the SEC.

The Fed oversees banks. So each of these companies went through a conversion to become a traditional bank so that they could tap the bailout bucks from the Fed.

Now the same group — the very ones that took on so much leverage last time that they helped to sink the system and had to change into traditional banks to access bailout funds — is complaining that their capital restrictions will be too high if they’re required to follow the new rules.

They shouldn’t worry. I’ve got the solution.

Instead of fretting about increased capital requirements because they’re deemed big enough to be a systemic risk if they failed, each of these behemoths could simply break themselves up into a number of smaller companies. As smaller entities, the subsequent firms would be under the threshold of “too big to fail,” and therefore the higher capital limits would no longer apply.

I think I can hear a pin drop.

There’s no way any of these companies will voluntarily break themselves up. If they did, then management would no longer get bonuses based on the earnings of really big companies, they’d have to settle for the pittance paid at smaller enterprises.

They’d also no longer have the clout and market-moving ability they enjoy today.

Of course, the financial system of the country would be better off because we’d no longer have just a few firms controlling so much wealth. With the concentration broken up, there would be no need to backstop any company because any one failure would not be a catastrophic blow to the system.

But we’re not talking about what’s good for the health of the financial system and the economy, we’re talking about what’s good for the “too big to fail” banks that think they’re getting a raw deal when it comes to higher reserve requirements.

The Fed is currently taking comments on the system. What are the odds that the Fed will introduce some compromise that allows these banks to cut their reserve requirements?

What’s the worst that could happen?

Rodney

P.S. Lance gives you some behind-the-scenes information about quantitative easing and what the Fed does to stimulate our economy… It’s really not all it’s cracked up to be. Read on below.

Want Financial Prosperity? Then Don’t Fight the Fed!

Don’t fight the Fed! I’m sure you’ve heard that at some point in the past, especially if you’ve been trading the markets or even studying them.

The Federal Reserve Bank has several tools it uses to help with its congressional mandates on price stability and maximum employment. When the Fed changes course on monetary policy by tightening or loosening money supply, investors should understand how it could affect their investments.

The Fed can lower or raise the Federal Funds rate and it can affect interest rates across the spectrum (short- to long-term rates). The Fed Funds rate is simply the overnight rate banking institutions pay to borrow money needed for their reserve requirements.

This is just one tool the Fed uses but it encourages banks to lend more… and invest more freely when the rate is lowered.

Raising or lowering the Fed Funds rate has been effective in helping stabilize prices in an inflationary environment. Since we’ve been at a zero rate for the past six years, the effectiveness on deflation has been suspect.

For that reason, the Fed instituted quantitative easing (QE) which, in essence, was a creation of money supply fueled by buying U.S. Treasury bonds created out of thin air and the purchasing agency guaranteed mortgage-backed securities. Those asset purchases injected about $85 billion per month into the money supply in an effort to create inflation. QE finally ended in October of last year after nearly six years.

And so, the Fed’s target inflation rate has been 2% per year and after six years and trillions of dollars that were created on the Fed’s balance sheet, we still sit under the 2% target inflation rate.

The main beneficiary of the Fed’s easy money policy has been the stock markets, otherwise known as “risk” assets, to gain acceptable investment returns in this environment. When the Fed finally reverses course and starts to tighten the money supply, make sure your investments move to safer assets like cash.

Please, don’t fight the Fed!

Lance

February 16, 2015

Iran’s Western Ideals: But Not For the Reasons You Think

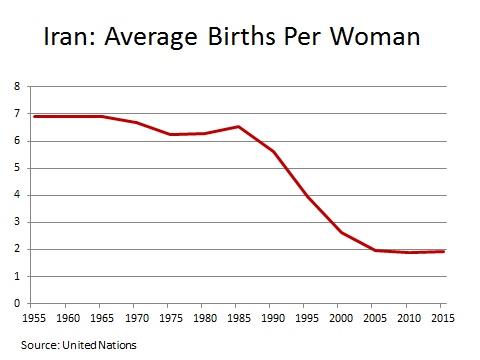

Last week, I wrote about China’s pending mother shortage and what it means for China’s economy in the decades ahead. Along those same lines, today I’m going to turn a popular misconception about Iran on its head.

There’s a widespread belief in the West that we’re being “outbred” by unstable countries that are hotbeds for terrorism, particularly in the Islamic world. To an extent, this is true. The average woman in Afghanistan, Iraq and Yemen, to pick three high-profile examples, can expect to have 5.1, 4.1 and 4.2 children in their respective lifetimes.

Iran had similarly high birthrates… before the Islamic revolution of 1979.

Ironically, Iran had much higher birthrates before the revolution, when it was officially a western-allied nation and women walked the streets freely with their heads uncovered. But just six years after the mullahs took over, the fertility rate collapsed. By 2005, it had fallen below the population replacement rate.

Today, at 1.9 children per women, the Iranian fertility rate is equal to that of the U.S. and actually lower than that of France!

Iran is changing. Women make up more than 60% of college students. With higher levels of female education, the average age of marriage and first childbirth rises and the smaller the average family size gets. According to the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies, the average age of marriage today is between 25 and 35 among men, and between 24 and 30 among women.

Divorce has a way of putting the brakes on family size, and about one out of three marriages in Tehran now end in divorce. For better or worse, Iran is starting to look a lot more “Western,” at least when it comes to family life.

What’s the takeaway here?

Iran won’t be a rogue state forever. We probably won’t see real political change while Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, is alive and kicking. But he’s also 75 years old and won’t be around forever. Change will come, and a lot sooner than most people realize.

Will the mullahs give up power without a fight? It’s doubtful… and Iran may never have a full-blown revolution and regime change. But as Iranian society changes, we should expect the government to, at the very least, subtly tone down its anti-western rants and start behaving accordingly..

Charles

The Power of the Cycle In Predicting Global Economic Trends

A few years ago, I was reading a sidebar in Barron’s by PIMCO director Paul McCulley. He was discussing an upcoming stock market peak for later that year… and interestingly enough, it was at the same time that sunspot cycles were predicted to peak.

This wasn’t the first time I’d heard respected analysts connect market activity to sunspot activity. Charles Nenner, a prominent cycle analyst believes there’s a plausible connection. So does Richard Mogey, founder of the Foundation for the Study of Cycles. By the way, that’s the caliber of speakers at our conferences and we were lucky to get him to present at our Irrational Economic Summit last year in Miami.

With McCulley joining the growing ranks of believers, it got me thinking… I thought that there had to be something to this theory. Do sunspot cycles affect the stock markets in any way?

I know it sounds crazy. First of all, I’m no stranger to being called crazy and second, success isn’t found inside the box…

As you know, NASA tracks and projects sunspot activity — that makes it more projectable. It’s discovered that movement on the sun’s surface ebbs and flows in cycles… just like everything else in life. As the cycle unfolds, the earth is bombarded by varying amounts of solar radiation. The high cycles can knock out satellites and communication systems. They also raise temperatures and rainfall. I explain this concept in more detail in my latest book, The demographic cliff.

I also recently wrote about how it’s affecting the farmland bubble, and as you know, I love to dig around and do my research. If I have a question, I dig in and find the answer.

Of course, rising and falling energy cycles certainly could have some impact on human behavior…

What was more interesting to me though was that this sunspot cycle is reputed to peak every 11 years — that’s why I first rejected it as I saw no correlations on 11-year cycles. So I went back and documented the peaks back over a hundred years only to discover that the real average is 10.3 years.

That’s when I got really interested.

You see there’s another cycle we follow closely, one first documented by Ned Davis. It actually has been one of the critical cycles in our research for decades. It’s called the Decennial Cycle and it tends to peak around the end of each decade and bottom in the second year of the next decade. And in the last cycle, there was a peak in early 2000 and a bottom in late 2002, right on cue.

The cycle then remains sideways to moderately up for stocks until the middle of the decade (i.e., late 2004 or late 2014), and then rises the most sharply again into the end of the decade.

Whether such cycles bottom earlier or later in the first few years of every decade has been related to when the four-year presidential cycle bottoms. That’s why we had major bottoms in 1962, 1970, 1982, 1990 and 2002.

These two cycles together — the 10-year Decennial Cycle and the four-year Presidential Cycle — created our best intermediate patterns for decades. The last time these two cycles should have bottomed together was late 2010 and a major crash and recession would have been expected more broadly between 2010 and 2012. But that didn’t happen…

When the economy weakened in 2010 to near zero growth, the Fed stepped in with QE2. It did it again in mid-to-late 2012 forward with two phases of QE3. All of which, I assumed at first, threw the otherwise reliable cycles out of kilter.

Or is there another explanation?

As I said before, the average sunspot cycle is 10 years. The last top was in early 2000… right at the top of the tech stock bubble. But that sunspot cycle bottomed years later than normal… and would you believe what happened next?

The stock market crash bottomed in early 2009… at exactly the same time the sunspot cycle bottomed.

NASA predicted a later than usual sunspot cycle to peak around mid-to-late 2013. And guess what? That’s when our analysis of stock patterns suggested that we could see a top in the markets.

We thought the Decennial Cycle failed for the first time in 50 years, but if sunspots are the cause, we just got an eccentric cycle that pointed down from late 2013 into late 2019, just as our spending wave and Geopolitical Cycles were also pointing down.

Subsequently, months of research into this sunspot cycle has shown that 88% of the major crashes, recessions, depressions and financial crises came in the down cycle, and most of the rest came close on either side. This is clearly no coincidence!

But here’s the important rub to note, this cycle peaked a little later than the scientists forecast… in February 2014.

Here’s the bottom line: this cycle, the most powerful I have discovered since the spending wave, looks like it peaked in early February of last year and now points down into late 2019 or early 2020.

The worst crashes come in the first 2.5 years after a peak just as Ned Davis’ Decennial Cycle suggested — so the greatest should be coming between mid-2015 and late 2016.

Harry

P.S. We consistently stress that demographic trends are key to an economy. And it is key in both developed and emerging nations. Charles explores that topic in a part of the world that may surprise you. Read on…

Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr.

February 13, 2015

Tread Carefully With Your Money, We Are Almost There!

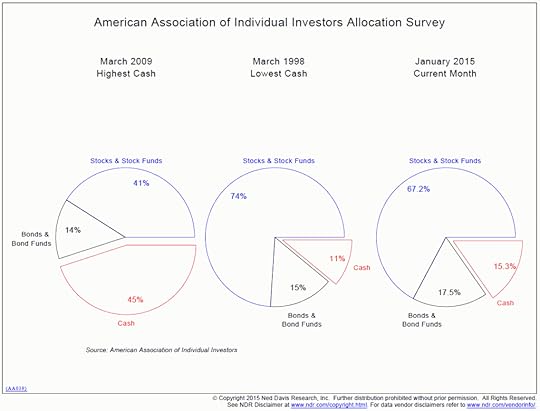

It’s a commonly held belief that many investors have missed the dramatic move higher that stocks have made since the bottom of 2009. I don’t buy it and statistics from the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) show I’m right. I’ll explain by way of this chart, which comes from a recent survey from the AAII and shows just how poorly, as a group, individual investors allocate capital to the markets…

The pie chart on the left represents the best buying opportunity in the stock market in the last generation. Yet, individual investors held the most cash during that period, while the equity allocation was the lowest. Of course, in the teeth of a crisis it’s difficult, emotionally and even physically, to push the button on the buy order and purchase stocks hand over fist. However, that’s exactly what you should be doing. In 2009, most people missed a huge opportunity!

The second pie chart represents March 1998, when individual investors had their equity allocations at 74% and a cash allocation of just 11%, giving them less firepower to buy stocks in the ensuing market collapse.

Today, we are not at either extreme. That’s why I think it’s important to be very careful how you allocate money in the market right now. For one thing, the cash position at 15% is at its lowest level since March 2008. So we’re at 16-year lows. For another, the equity allocation, at 67%, is the second-highest level since the 2009 market low. Typically, a 70% allocation to equities is met with intermediate market tops. That means we’re almost there.

Could we go higher? Yes, for sure! But not by much because there’s little ammunition left that individuals can throw at the market at this point.

So, like I said last week, tread carefully in the markets right now. Things are very toppy.

And keep reading. I have my eye on several short-selling opportunities that are growing increasingly attractive. The more the market rallies, and the less cash there is to allocate to equities, the more vulnerable this bubble becomes. This means that if any bad news filters out on individual companies, the downside will be greater, setting us up for more profitable shorts.

I’ll have more details soon.

John Del Vecchio

Contributing Editor

The Jimmy Buffett Approach to Pensions and Fiscal Policy

In South Florida there is a constant background theme of everything Jimmy Buffett. His music emanates from stores and restaurants while land shark and parrot-head references abound.

This doesn’t bother me, because I’m a fan of his music, most of which is concerned with sunshine, beach drinks, and enjoying yourself in everyday life. But there’s one line from an old song that haunts me as I read daily financial headlines… “I keep laughing so they don’t pick me.”

It’s not a happy sentiment.

Every time a politician stands up and claims that his proposal is going to help “us,” I have the sneaking suspicion that I am considered one of “them.” I pay federal income and capital gains taxes.

Just those two facts alone put me in a minority and make it more likely that I’ll keep less of my earnings in the years ahead as the cost of running our national government goes up

While this is always a general concern, I really get nervous when I see big fiscal problems looming and no one is offering solutions. The latest thing on my radar is pensions, or more specifically, the unfunded pensions of cities and states.

This topic isn’t new, which is the problem. I covered it extensively eight years ago in our special report, The Death of Pensions, and little has changed since then. Some states and cities have worked on the issue half-heartedly, raising some employee contribution levels and appointing commissions to find solutions.

But few have done the hard work of raising pension sponsor contributions (what the cities and states must pay) or working with current and future retirees to set these plans on sustainable paths. Meanwhile, the pension plans in the most trouble keep falling further behind.

Bloomberg — as well as many other information organizations — ranks the states by their pension funding level. Anything at 70% or below is considered at risk of not being able to meet its obligations.

Based on 2013 funding levels (the last year available), 26 states fall under the 70% threshold. The winner in this category is Illinois, which has a mere 39.3% of the assets it needs to meet its obligations. That’s down from 43.4% in 2011, and 50.6% in 2009.

This is an ugly trend, but you might be wondering what it has to do with me, as I listen to Jimmy Buffett in the Sunshine State. When financial problems get too big, everyone looks for the deepest pockets, which, of course, exist at the federal government.

The last governor of Illinois at least tried to address some of the issues facing the pension system, but his proposals were deemed unconstitutional at the state level. Do we have to wait for a state to declare bankruptcy over these issues before we put some sort of structure in place to deal with the problems?

Oddly enough, the answer is probably, “Yes.” State constitutions govern how cities, counties, and states deal with their pensions. For those states with a constitutional guarantee of their contracts, any vested pension is ironclad… up to a point.

A judge in California ruled that the city of Stockton could adjust pensions for current and future retirees because the city was in bankruptcy, which is a federal statute. The city backed down, not wanting a protracted legal fight with the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), but the ruling is still out there.

But if it comes to pass that Illinois, or any other state for that matter, declares it can’t pay its pensions, would the federal government allow the pensions to be cut? Or would our elected officials come up with some way to backstop the payments? It turns out that just last month a little light was shed on the subject.

U.S. Congressman Jason Chaffetz from Utah offered up House Resolution 41 last month, wanting to shine a bright light on the looming public pension issue and the role of the federal government.

The resolution, which doesn’t have the force of law but is meant to frame debates in session, called for recognizing that the federal government operates with huge debt and deficits of its own, and that federal legislators have no intention of bailing out state and city pension plans or retirement health care systems.

As several government tracking websites have put it, this resolution has zero chance of passing. Our elected officials have zero interest in reminding cities and states that their obligations are exactly that… theirs.

Hmm.

It could be that no one wants to think about it right now. It could also be that because there is no easy solution, talking about it seems pointless. But… not talking about it only leaves the problem for another day, and it’s getting bigger, not smaller.

At the low end, using very rosy estimates of future returns and state contributions, the size of the gap in funding for public pensions is $1 trillion. Only 15 of the states are making their required pension contributions.

It’s true that none of the state pension funds will go broke this year or next, but do we have to wait until all the assets are gone before we work on solutions?

It could be that 2015 brings us all some answers. Next year, the city of Chicago will have to increase its pension contributions from roughly $430 million to $1 billion, which is almost impossible.

This leaves the city in a quandary. They cannot afford to make their payments, but workers and retirees have signaled they aren’t willing to negotiate. What’s a city to do?

It won’t take unionized city workers long to figure out that the U.S. government rode to the rescue of United Auto Workers (UAW) in 2009, guaranteeing their gold-plated pensions at 100% while selling white-collar workers and non-UAW members down the river. These union dues-paying employees and retirees will ring up their local Congressmen and demand some sort of federal bailout as well.

When Congress looks around for how to pay for all of this, I’ll be the one in the back, singing old Jimmy Buffett songs.

Seriously though… if all of this causes your eyes to glaze over and makes you a little angry, there is one way to stop the money grab from reaching too far into your wallet — shrink your taxable footprint.

I know that I say this about once a quarter, but there simply is no substitute for getting Uncle Sam — or any other taxing authority — out of your financial planning. I don’t try to push my taxes to zero, but I do try to be efficient with my household finances and investments.

Every penny counts!

Rodney

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

February 12, 2015

The Future of Health Care: Cut Out the Insurance Middleman

We’re used to random health care insurance increases of 10% to 20% every year or so. But in December my policy was simply terminated without anything changing on my part.

When I applied for a new policy I found out the reason. It was too affordable. The lowest price I got was 44% higher. Is this due to Obamacare or just continued insanity in health care costs?

It’s likely that it’s both.

Just a few weeks ago, I read an interesting article in Time magazine “What I Learned From My $190,000 Open-Heart Surgery,” by Steven Brill on January 19.

To make a long story short, the main point was to align the interests of quality care and low costs by having the large care provider systems become their own insurance company. The two-pronged approach of prescribing the care and paying the bill cuts out a layer of bureaucracy and eliminates that incentive that the U.S. is famous for…

Over prescribing!

I’ve often suggested that the insurance system should revolve around catastrophic care and then people use their saved premiums to pay for their recurring and routine care so the patient becomes more accountable for the costs vs. the benefits. In the typical system where insurance covers 80% or more, the patient has the incentive to ask for more care, not less — and of course, the doctors and specialist providers love that.

Do you know that only 12% of health care costs are paid out of pocket? It was 50% in 1960. No wonder there’s no accountability!

I also favor a one-payer system for the most routine and basic services, which would save massive overhead and create greater economies of scale. Households that want more can always pay for it through insurance or directly.

You think it’ll happen? No. It just isn’t going to happen in this country… even though it’s been proven efficient and effective in many others.

What I like about this approach is that it levers the free market system that we already favor and it brings in a new angle. Have the care providers be responsible for both the quality and the costs.

They are, after all, the sophisticated party in a complex arena of knowledge — more so than most patients that are biased by the extreme fear that accompanies any health threat.

As patients, we just aren’t rational most of the time, even perhaps with the right incentives, and that’s why we overspend and do so many things that aren’t proven to be effective and can be very expensive. We’ll pay anything when our life is threatened, or to keep a loved one alive for a few extra months.

And again, the doctors and providers only benefit while our insurance costs keep going through the roof.

It’s well-known now that our costs per capita of health care are roughly double that of other western countries. We spend $3 trillion each year and it’s constantly increasing. That is more than the next 10 countries combined: Japan, Germany, France, China, the U.K., Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain and Australia.

Can you believe that?

We overuse care and expensive machinery. We have 31.5 MRI machines per 1 million people vs. 5.9 in the U.K. It is the largest industry and employs 1/6 of the workforce. And not surprisingly, it spends twice as much on lobbying as the next largest military-industrial complex.

In his article, Brill uses the examples of some of the up-and-coming industry leaders in quality and in costs.

He starts with the Cleveland Clinic whose heart program dominates his region while attracting clients from all over the world. Toby Cosgrove runs this $6 billion franchise, but claims he can’t grow too much or the FTC would be all over him. Brill suggests that we should encourage the dominance of specialty firms like this instead of restrict them. Such specialists are the answer to quality care.

He got his best insights from Jeffrey Romoff, CEO of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). After growing to dominate his market, he’s starting his own insurance company and looking to divorce from Highmark Insurance. His in-house company will provide insurance that provides full access to his broad range of facilities.

The promise is local, high-quality care — and UPMC foots the bill… so there is finally an incentive against inflating costs or overtreating! There would also be substantial savings in overheads and bureaucracy, more like the single-payer approach.

In fact, this is more like a decentralized and free market version of single payer.

There would need to be some simple regulations if such a system was encouraged: self-insuring regional health care providers who get sanctioned as such an oligopoly would have to make concessions for the benefits of greater market dominance:

There would have to be a minimum of two such dominant providers in each region, no monopolies, only oligopolies. Larger markets like New York or L.A. should have four or more.Cap the operating profits at 8% vs. 12% on average currently.Cap the professional salaries at something like 60 times the lowest paid workers.A streamlined process for appeals by patients who believe they were denied appropriate care.The CEO must be a licensed physician, not just a bean counter, to ensure quality of care is paramount.Such sanctioned oligopolies would be required to insure a certain percentage of Medicaid patients at a stipulated discount and charge no more to uninsured patients than they would charge the competing insurance companies that they accept. Brill estimates these changes should save at least 20% of health care costs, or $400 billion a year.

All of this won’t get us to where most western systems are at, but that sounds like a pretty good start to me. It’s about making the free market system both more consolidated for scale and more accountable for care and costs.

Harry

P.S. Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr.