Robert H. Edwards's Blog: Great 20th century mysteries

January 17, 2025

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: WanderLearn Part 3/3

On the WanderLearn channel, D. B. Cooper and Flight 305, Part 3/3, is now live with Francis Tapon and myself, at https://youtube.com/watch?v=UFNQ-i6xCPM

Image credit: Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

In this episode, we consider what the hijacker's actions and words tell us about his prior life experience; whether that experience included military service; and what kind of occupation might have given him the necessary and sufficient knowledge to pull off the hijacking.

We go on to consider the only irrefutable trace of the hijacker's passage: the three bundles of ransom money, once worth about $5,800, found in 1980 at Tena Bar on the Columbia River. Keeping Occam's Razor in mind, we reflect on the simplest hypotheses that might account for the money's journey to Tena Bar.

Finally we look to draw together the strands, and to construct a picture, not of the hijacker's identity which is not our concern, but of the possible next steps that could be taken to shed light on this 53-year old mystery.

Image credit: Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

In this episode, we consider what the hijacker's actions and words tell us about his prior life experience; whether that experience included military service; and what kind of occupation might have given him the necessary and sufficient knowledge to pull off the hijacking.

We go on to consider the only irrefutable trace of the hijacker's passage: the three bundles of ransom money, once worth about $5,800, found in 1980 at Tena Bar on the Columbia River. Keeping Occam's Razor in mind, we reflect on the simplest hypotheses that might account for the money's journey to Tena Bar.

Finally we look to draw together the strands, and to construct a picture, not of the hijacker's identity which is not our concern, but of the possible next steps that could be taken to shed light on this 53-year old mystery.

Published on January 17, 2025 08:44

•

Tags:

dbcooper, flight305, francistapon, tenabar, wanderlearn

January 11, 2025

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: on WanderLearn

The second of three episodes of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305, with Francis Tapon and myself, is live on the WanderLearn channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BsXtD... (video file) and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gR86... (audio only).

We start with an outline of some elements of the hijacker's planning process, and the criteria that led to his choice of Northwest Flight 305.

We go on to discuss the precursor flights, by Boeing out of Hoquiam and Boeing Field, and by Southern Air Transport (fronting for the CIA) out of Takhli, which demonstrated that it was possible and safe to parachute from a Boeing 727.

Image credit: Robert H Edwards and Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

We start with an outline of some elements of the hijacker's planning process, and the criteria that led to his choice of Northwest Flight 305.

We go on to discuss the precursor flights, by Boeing out of Hoquiam and Boeing Field, and by Southern Air Transport (fronting for the CIA) out of Takhli, which demonstrated that it was possible and safe to parachute from a Boeing 727.

Image credit: Robert H Edwards and Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

December 28, 2024

Mallory, Irvine, Everest: on Medium

Belated thanks to author Peter Miller for his extensive quotations from Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One in Medium of June 24, 2024.

https://medium.com/@tgof137/the-hundr...

Screenshot from Peter Miller's article on medium.com of June 24, 2024. Image credit: Peter Miller / Robert H Edwards.

https://medium.com/@tgof137/the-hundr...

Screenshot from Peter Miller's article on medium.com of June 24, 2024. Image credit: Peter Miller / Robert H Edwards.

Published on December 28, 2024 01:02

•

Tags:

everest, irvine, mallory, peter-miller-medium-com

December 24, 2024

Mallory, Irvine, Everest: Everest Mystery

Many thanks to Thom Dharma Pollard for his kind words on Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, 2024), on the Everest Mystery channel.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=gxhDXeqZMRE

Image credits: Thom Dharma Pollard / Everest Mystery.

Mr Pollard says:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=gxhDXeqZMRE

Image credits: Thom Dharma Pollard / Everest Mystery.

Mr Pollard says:

"Some are starting to believe that the body [of Andrew Irvine] probably was thrown down as early as 1975: which would support the research of a great Everest historian. His name is Bob Edwards.To set the record straight: I have not proposed any form of human agency for the descent of Irvine’s remains to the Central Rongbuk Glacier.

He wrote this book Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One; and in a series of blog posts which I'm showing you on the screen now, he does mathematical calculations of how far that boot or the body of Irvine would have traveled had it been thrown down the mountain in any given year.

So, for any sleuths out there who are fascinated with the minutia of the mystery of Mallory and Irvine, this is a good book, because it goes into all the details, and it also lists the key elevations and locations of all the different clues of the mystery."

Published on December 24, 2024 00:18

•

Tags:

everest, irvine, mallory, thom-pollard

December 22, 2024

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: WanderLearn Part 1/3

The first of three episodes of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305, with Francis Tapon and myself, is live on the WanderLearn channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTJXq... (video file) and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1V9ow... (audio only).

Despite the provocative headline on YouTube, I do not fault the FBI's handling of the case of Flight 305. Some aspects, for example the concept of the "sled test" flight, were brilliant.

I think that the FBI relied on outside experts who did not provide a full picture of the uncertainties in the data, especially with regard to the flight timing, wind speeds and directions, and the distinction between the "oscillations" and the "pressure bump".

Part 2 will be on December 27, 2024, and Part 3 on January 10, 2025.

Image credit: Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

Despite the provocative headline on YouTube, I do not fault the FBI's handling of the case of Flight 305. Some aspects, for example the concept of the "sled test" flight, were brilliant.

I think that the FBI relied on outside experts who did not provide a full picture of the uncertainties in the data, especially with regard to the flight timing, wind speeds and directions, and the distinction between the "oscillations" and the "pressure bump".

Part 2 will be on December 27, 2024, and Part 3 on January 10, 2025.

Image credit: Francis Tapon / WanderLearn.

Published on December 22, 2024 13:07

•

Tags:

dbcooper, fbi, francis-tapon, wanderlearn

September 30, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: doubled letters

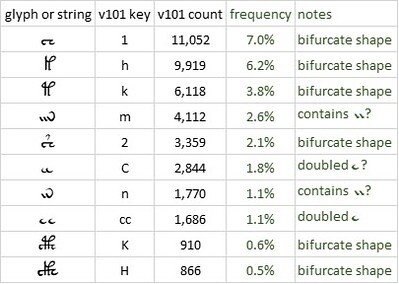

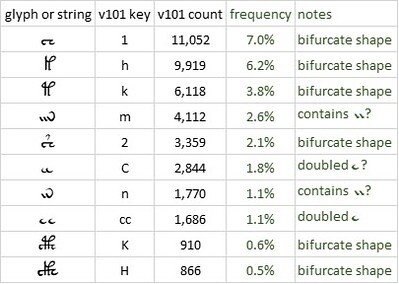

In Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript, there are very few glyphs that are repeated, in the sense that, for example, the letter e is repeated in the English word "see".

The only frequent instance is {cc}, which occurs 1,686 times; after that, {oo} occurs just 55 times.

There are a few glyphs that visually resemble doubles of other glyphs, notably {C} which resembles {cc}; but Claston chose to give them separate keys. There are several common glyphs, especially {m} and {n}, that could be interpreted as having an embedded double {i}. And there are some common glyphs, notably {1}, {h} and {k}, which have a bifurcate structure and look like they might represent doubled letters or bigrams in the presumed precursor languages.

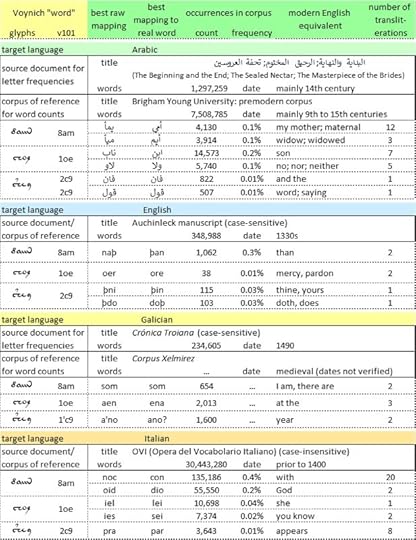

Below is a selection of common glyphs which look as if they might represent or contain doubled glyphs, together with the {cc} string.

This is a subjective selection of glyphs which have the visual appearance of representing or containing doubled glyphs or bigrams. Author's analysis, based on v101 transliteration. Frequency is calculated as count of glyph or string in v101, divided by total glyph count in v101. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjLwVA

Much of my research on the Voynich manuscript has been based on the following working assumptions:

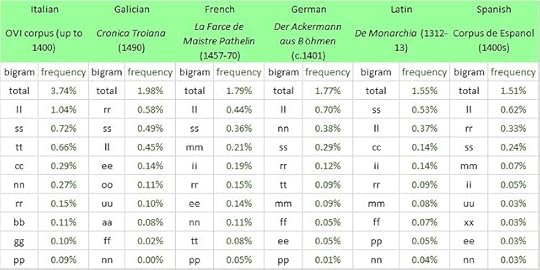

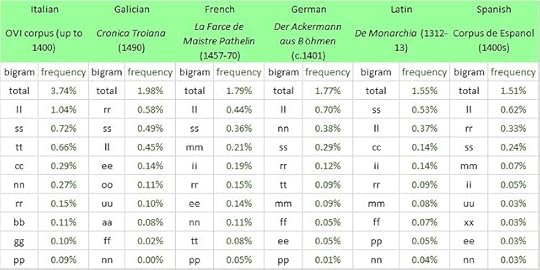

Most European natural languages have some doubled letters. I calculated the frequencies of doubled letters in several medieval European languages, with the results shown in the table below. In these languages, there was no doubled letter whose frequency was more than 1.04 per cent of the total letter count.

The frequencies of the most common doubled letters in selected medieval European languages. Frequencies are calculated as counts of bigrams, divided by total counts of letters in the respective corpora. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjL4yF

If we stick with the assumption that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping from the precursor documents, it seems a necessary inference that glyphs such as {1}, {h}, {k} and {m} cannot represent or contain representations of doubled letters. These glyphs are simply too frequent.

To my mind, the Voynich producer might have instructed at least two possible treatments of doubled letters:

Could doubled letters be distinguished?

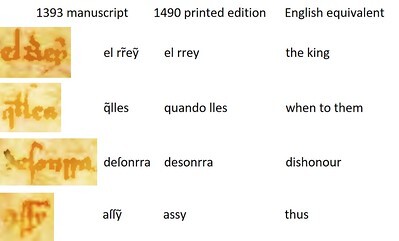

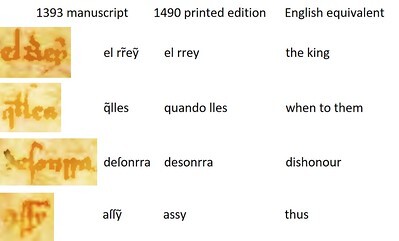

In passing we might observe that if the Voynich scribes were working from manuscripts in the precursor languages, the doubled letters might not have been readily distinguishable from single letters. Below are some examples from the 1373 manuscript of Cronica Troiana. I conjecture that the Voynich scribes were working men who were paid by the page, and that the Voynich producer did not instruct or encourage them to make editorial or creative decisions. Faced with a symbol that might or might not be a doubled letter, I conjecture that the scribes might have used a different glyph from that for a clearly defined single letter.

Some examples of doubled letters in the 1373 manuscript of Crónica Troiana by Fernán Martis; with their representations in the printed edition of 1490, and their equivalents in modern English. Author's analysis.

Re-ordering glyphs within “words”

The above tests would make sense if the glyphs in the Voynich “words” followed the same order as the letters in the precursor words. However, as I have observed in several articles on this platform, it is conceivable that they do not. Mary D'Imperio's concept of "the five states", and Massimiliano Zattera's identification of a "slot alphabet", permit us to imagine that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes, after mapping from letters to glyphs, to re-order the glyphs in each “word”.

We can see how this might work by re-ordering a hypothetical source document. Let us say that the document is the manuscript of Cronica Troiana in Galician, published by Fernan Martis in 1373. The first line reads:

This example should demonstrate that some form of re-ordering, whether based on an existing alphabet or on some system invented by the Voynich producer, will create doubled and tripled glyphs where doubled letters were not originally present. To take a simple example: the Voynich “word” {8am}, which appears to have three glyphs, could be interpreted as a five-glyph “word”, namely {8aiiN]. This “word” in turn could be a re-ordering of a prior ”word”, for example {i8aNi} or {iNa8i}, which retained the order of the precursor letters.

To test this hypothesis, again we would need to create variants of our source corpora. For example, with various online tools we can easily reproduce a variant of the full text of Cronica Troiana in which the letters of each word follow the order of the Latin alphabet. On its own, this process will not change the letter frequencies, and therefore will not change the reverse-engineered mapping from letters to glyphs. However, we could then apply one of the treatments that we imagined on the part of the Voynich scribes, namely:

In either case, the letter frequencies would change; therefore the ranking of letters by frequency would change; and therefore the mappings between glyphs and letters would change. We could then map some common Voynich “words”, such as {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}, to Galician. In comparison with our earlier mappings, this might yield more real words, and better still, more common real words, in Galician. If so, we might suspect that we were onto something. Again, I will investigate tests of this nature, and post on this platform.

Few doubled letters?

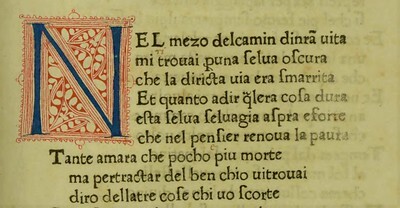

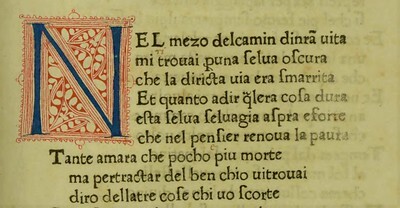

There remains the possibility that the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from documents in languages which had few doubled letters. Italian, as represented by the 1472 edition of La Divina Commedia would fit for this description.

The first nine lines of the first printed edition of La Divina Commedia (dated 1472), which contain just two instances of doubled letters: "smarrita" and "dellatre".

The only frequent instance is {cc}, which occurs 1,686 times; after that, {oo} occurs just 55 times.

There are a few glyphs that visually resemble doubles of other glyphs, notably {C} which resembles {cc}; but Claston chose to give them separate keys. There are several common glyphs, especially {m} and {n}, that could be interpreted as having an embedded double {i}. And there are some common glyphs, notably {1}, {h} and {k}, which have a bifurcate structure and look like they might represent doubled letters or bigrams in the presumed precursor languages.

Below is a selection of common glyphs which look as if they might represent or contain doubled glyphs, together with the {cc} string.

This is a subjective selection of glyphs which have the visual appearance of representing or containing doubled glyphs or bigrams. Author's analysis, based on v101 transliteration. Frequency is calculated as count of glyph or string in v101, divided by total glyph count in v101. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjLwVA

Much of my research on the Voynich manuscript has been based on the following working assumptions:

• that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes to made a one-to-one transcription from documents in natural languages,Since evidence exists that Voynich purchased the manuscript in Frascati, Italy, I chose to prioritise the medieval languages used within some delimited geographical radius of Italy: for example, French, Italian or Latin.

• and that those languages were more likely to be European than not.

Most European natural languages have some doubled letters. I calculated the frequencies of doubled letters in several medieval European languages, with the results shown in the table below. In these languages, there was no doubled letter whose frequency was more than 1.04 per cent of the total letter count.

The frequencies of the most common doubled letters in selected medieval European languages. Frequencies are calculated as counts of bigrams, divided by total counts of letters in the respective corpora. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjL4yF

If we stick with the assumption that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping from the precursor documents, it seems a necessary inference that glyphs such as {1}, {h}, {k} and {m} cannot represent or contain representations of doubled letters. These glyphs are simply too frequent.

To my mind, the Voynich producer might have instructed at least two possible treatments of doubled letters:

• to ignore them: that is, to treat any doubled letter as a single letterTo test these hypotheses, it would be necessary to take each source corpus and create two variants, reflecting the above processes respectively; to recalculate the letter frequencies; and to try some mappings of selected Voynich “words” to the language in question. I will explore these tests and post the results on this platform.

• to treat them as distinct from their single counterparts: that is; to assign one glyph to the single letter and another to the doubled letter.

Could doubled letters be distinguished?

In passing we might observe that if the Voynich scribes were working from manuscripts in the precursor languages, the doubled letters might not have been readily distinguishable from single letters. Below are some examples from the 1373 manuscript of Cronica Troiana. I conjecture that the Voynich scribes were working men who were paid by the page, and that the Voynich producer did not instruct or encourage them to make editorial or creative decisions. Faced with a symbol that might or might not be a doubled letter, I conjecture that the scribes might have used a different glyph from that for a clearly defined single letter.

Some examples of doubled letters in the 1373 manuscript of Crónica Troiana by Fernán Martis; with their representations in the printed edition of 1490, and their equivalents in modern English. Author's analysis.

Re-ordering glyphs within “words”

The above tests would make sense if the glyphs in the Voynich “words” followed the same order as the letters in the precursor words. However, as I have observed in several articles on this platform, it is conceivable that they do not. Mary D'Imperio's concept of "the five states", and Massimiliano Zattera's identification of a "slot alphabet", permit us to imagine that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes, after mapping from letters to glyphs, to re-order the glyphs in each “word”.

We can see how this might work by re-ordering a hypothetical source document. Let us say that the document is the manuscript of Cronica Troiana in Galician, published by Fernan Martis in 1373. The first line reads:

“Agora diz oconto q̃ os gregos oūūerō grā peſar q̃ndolles ercoɫs + jāāſon contarō agrā”which contains three instances of doubled letters: “ūū”, “ll” and “āā”. Suppose that we re-order the letters in each word, on the basis of the Latin alphabet. The result is:

“aAgor diz cnooot q̃ os eggros eoōrūū grā aeprſ dellnoq̃s ceɫors + āājnoſ acnoōrt aāgr”Now there are at least seven and potentially ten instances of doubled letters, depending on whether we treat accented letters as different from unaccented letters, and upper case as different from lower case.

This example should demonstrate that some form of re-ordering, whether based on an existing alphabet or on some system invented by the Voynich producer, will create doubled and tripled glyphs where doubled letters were not originally present. To take a simple example: the Voynich “word” {8am}, which appears to have three glyphs, could be interpreted as a five-glyph “word”, namely {8aiiN]. This “word” in turn could be a re-ordering of a prior ”word”, for example {i8aNi} or {iNa8i}, which retained the order of the precursor letters.

To test this hypothesis, again we would need to create variants of our source corpora. For example, with various online tools we can easily reproduce a variant of the full text of Cronica Troiana in which the letters of each word follow the order of the Latin alphabet. On its own, this process will not change the letter frequencies, and therefore will not change the reverse-engineered mapping from letters to glyphs. However, we could then apply one of the treatments that we imagined on the part of the Voynich scribes, namely:

• replace each doubled or tripled letter with a single letter; so that, for example “cnooot” becomes “cnot”These kinds of treatment might help to address both the rarity of doubled glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, and also the relatively low average length of the Voynich “words”, in comparison with words in most natural languages.

• replace each doubled letter with a unique but different Unicode symbol: so that for example, “cnooot” becomes “cnoôt” or “cnôot”.

In either case, the letter frequencies would change; therefore the ranking of letters by frequency would change; and therefore the mappings between glyphs and letters would change. We could then map some common Voynich “words”, such as {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}, to Galician. In comparison with our earlier mappings, this might yield more real words, and better still, more common real words, in Galician. If so, we might suspect that we were onto something. Again, I will investigate tests of this nature, and post on this platform.

Few doubled letters?

There remains the possibility that the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from documents in languages which had few doubled letters. Italian, as represented by the 1472 edition of La Divina Commedia would fit for this description.

The first nine lines of the first printed edition of La Divina Commedia (dated 1472), which contain just two instances of doubled letters: "smarrita" and "dellatre".

Published on September 30, 2024 12:48

•

Tags:

cronica-troiana, divina-commedia, voynich

September 27, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: manuscripts and printed documents

As I observed in my new book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), the Voynich manuscript was written on a vellum based on calfskin. Samples from four pages have been analysed for their radiocarbon content. These analyses established that, with a high probability, these pages were produced in the first half of the fifteenth century.

Around 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the first movable-type printing press in Europe. In 1455, he published the celebrated Gutenberg Bible.

In the light of these dates, and with regard to the nature of the presumed source documents of the Voynich manuscript, it seems to me that at least two hypotheses are permissible

There is a prior manuscript edition of Crónica Troiana, dated 1373, written by Fernán Martis as a prose translation from the French Roman de Troie by Benoît de Sainte-Maure. I have a scanned pdf of the Martis manuscript; it has OCR text but the OCR is not usable. From a comparison of the first pages of the 1373 and 1490 editions, it's clear that the printed edition expanded the earlier abbreviations and concatenations, for example:

The first six lines of Crónica Troiana, in the 1373 manuscript by Fernán Martis and in the first printed edition of 1490. Image credits: Fernán Martis, additional graphics by author. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qijED9

I have provisionally reconstructed a digital text of the Martis manuscript by identifying some of the most common abbreviations and concatenations, and reverse-engineering them from the 1490 text. The resulting digitised text of the manuscript should permit an alternative calculation of the Galician letter frequencies, and thereby an alternative mapping from Voynich glyphs to Galician letters.

Around 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the first movable-type printing press in Europe. In 1455, he published the celebrated Gutenberg Bible.

In the light of these dates, and with regard to the nature of the presumed source documents of the Voynich manuscript, it seems to me that at least two hypotheses are permissible

• that the text was written in the second half of the fifteenth century: in which case, printed documents would have been available in many cities in Europe (and I conjecture that the Voynich producer might have preferred to use printed documents, for their low cost, uniformity and ease of distribution)In an earlier article on this platform, I reported on my provisional mappings of selected Voynich "words" to words in medieval Galician, as represented by the first printed edition of Crónica Troiana, published in 1490.

• that the text was written in the first half of the fifteenth century, in which case the Voynich producer would probably have had only manuscripts as source documents.

There is a prior manuscript edition of Crónica Troiana, dated 1373, written by Fernán Martis as a prose translation from the French Roman de Troie by Benoît de Sainte-Maure. I have a scanned pdf of the Martis manuscript; it has OCR text but the OCR is not usable. From a comparison of the first pages of the 1373 and 1490 editions, it's clear that the printed edition expanded the earlier abbreviations and concatenations, for example:

• "oconto" in 1373 became "o conto" ("the story") in 1490

• "q̃ndolles" in 1373 became "quando lles" ("when to them") in 1490.

The first six lines of Crónica Troiana, in the 1373 manuscript by Fernán Martis and in the first printed edition of 1490. Image credits: Fernán Martis, additional graphics by author. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qijED9

I have provisionally reconstructed a digital text of the Martis manuscript by identifying some of the most common abbreviations and concatenations, and reverse-engineering them from the 1490 text. The resulting digitised text of the manuscript should permit an alternative calculation of the Galician letter frequencies, and thereby an alternative mapping from Voynich glyphs to Galician letters.

Published on September 27, 2024 12:47

•

Tags:

crónica-troiana, galician, voynich

September 23, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: filtering the languages

In my new book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), I have outlined a strategy whereby the interested reader could pursue his or her own ideas as to the underlying meaning of the mysterious Voynich manuscript. In recent articles on this platform, I reported some results of a specific strategy for identifying the precursor languages of the manuscript, or at least filtering the more probable ones. I called it the [8am} strategy.

The strategy is based on a process of mapping selected common “words” in the Voynich manuscript, to text strings in selected medieval languages.

I started with the "word" represented by {8am} in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. This is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript, occurring 739 times.

The first trial mappings yielded some reason to think that {8am} might map to real words in at least four medieval languages, as follows:

The Voynich “words” {8am}, {1oe) and {2c9},

rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image

credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

The {8am} process

For each Voynich "word" to be tested, the process involves the following steps:

As in the first trial mappings, I tested up to thirty-seven different transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all of my own devising but derived from Claston’s v101. The target medieval languages were those that I had selected for reasonable geographical proximity to Italy, where Wilfrid Voynich was said to have rediscovered the manuscript. Initially I focused on Arabic, English, Galician and Italian, which had yielded encouraging results for the “word” {8am}. My team is currently working on other languages.

Mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}

To cut to the chase: these tests in most cases yielded mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to real and relatively common words in all four languages:

Selected mappings of the "words" [8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to words in selected medieval languages. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q72NkY

In most cases, it was necessary to re-order the letters in the raw text strings: sometimes, to reverse the order. I felt that this was to be expected, given that, as D’Imperio and Zattera observed, the glyphs follow a rather rigid sequence within “words”. Since I do not know of any such sequencing in natural languages, I was inclined to one of the following views:

Next steps

To my mind, the next steps should be as follows:

The strategy is based on a process of mapping selected common “words” in the Voynich manuscript, to text strings in selected medieval languages.

I started with the "word" represented by {8am} in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. This is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript, occurring 739 times.

The first trial mappings yielded some reason to think that {8am} might map to real words in at least four medieval languages, as follows:

• Arabic as written in the fourteenth century, represented mainly by Ibn Kathir’s البداية والنهاية (The Beginning and the End), a text which I received by courtesy of Dr Mohsen MadiThe next step was to attempt mappings of other common Voynich “words”. For this purpose, I selected the following “words”, which have no glyphs in common with {8am}:

• English as written in the 1330s, represented by the Auchinleck manuscript

• Galician as written in the 1490s, represented by the first printed edition of Crónica Troiana

• Italian as written prior to 1400, represented by the OVI corpus, or Opera del Vocabolario Italiano.

• {1oe}: the seventh most common “word” in the manuscript, occurring 400 times

• {2c9}: the 22nd most common “word” in the manuscript, occurring 209 times.

The Voynich “words” {8am}, {1oe) and {2c9},

rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image

credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

The {8am} process

For each Voynich "word" to be tested, the process involves the following steps:

• testing multiple transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, in permutations with multiple precursor languages;As I reported earlier: my transliterations allow for varying definitions of the glyphs. For example, I have considered the possibilities that:

• for each permutation, mapping the “word” to a text string in the target language, using frequency rankings as the basis for the mapping;

• and for each such string, searching a suitable corpus of the target language for that string as a real word.

• {m} might be not one glyph but two or three, possibly equivalent to {in} or {IN} or {iiN} in the v101 transliteration;Mary D'Imperio's "five states" and Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet" had suggested that the Voynich scribes might have re-ordered the glyphs within "words". In cases where the raw mapping yielded a text string which was not a meaningful word in the target language, I allowed for the possibility of re-ordering or reversing the letters in the text string.

• {1} might be two glyphs, possibly equivalent to {Ec};

• {2} might be a variant of {1}, with a diacritic of unknown significance: possibly a vowel analogous to the dammah (ـــُــ) in Arabic; or a wild card with multiple meanings.

As in the first trial mappings, I tested up to thirty-seven different transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all of my own devising but derived from Claston’s v101. The target medieval languages were those that I had selected for reasonable geographical proximity to Italy, where Wilfrid Voynich was said to have rediscovered the manuscript. Initially I focused on Arabic, English, Galician and Italian, which had yielded encouraging results for the “word” {8am}. My team is currently working on other languages.

Mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}

To cut to the chase: these tests in most cases yielded mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to real and relatively common words in all four languages:

Selected mappings of the "words" [8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to words in selected medieval languages. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q72NkY

In most cases, it was necessary to re-order the letters in the raw text strings: sometimes, to reverse the order. I felt that this was to be expected, given that, as D’Imperio and Zattera observed, the glyphs follow a rather rigid sequence within “words”. Since I do not know of any such sequencing in natural languages, I was inclined to one of the following views:

• that the Voynich producer had given the scribes not only a mapping from letters to glyphs, but also an “alphabet” as a basis for re-ordering glyphs within “words”: perhaps something along the lines of Zattera’s “slot alphabet”;In most cases, there were multiple transliterations which yielded the same raw mapping.

• or that, if the precursor language was Arabic, the scribes were unaware (or were instructed to ignore) that Arabic was written from right to left, and had taken the leftmost letter to be the first;

• or that the producer had simply instructed the scribes to reverse the order of the letters within words: possibly as a form of simple encipherment.

Next steps

To my mind, the next steps should be as follows:

• to map some other common “words” in the Voynich manuscript: preferably “words” with some different glyphs from those in the first three, such as {4ohan}, which I am inclined to read as {④han}If this process yields encouraging results, we can contemplate mappings of whole lines.

• to identify, if possible, those transliterations which consistently map the common Voynich “words” to real and common words in one target language or another.

Published on September 23, 2024 00:13

•

Tags:

arabic, auchinleck, cronica-troiana, fernan-martis, galician, ibn-kathir, voynich

August 28, 2024

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: review

Kind comment from a reader in the UK:

An extract from one of my early designs for the cover of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021). Image credit: author.

"For enthusiasts of the DB Cooper mystery, I cannot recommend more highly Dr Bob Edward's thoroughly researched and beautifully presented 'Flight 305'."

An extract from one of my early designs for the cover of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021). Image credit: author.

August 19, 2024

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: review

Kind review of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 from a reader in Ohio:

An extract from one of my early designs for the cover of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021). Image credit: author.

"Keep up the good work--I loved your Flight 305 book and I find the more focused, rational, and science minded posts you are making to be much more compelling than almost everything out there in the Vortex."

An extract from one of my early designs for the cover of D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021). Image credit: author.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers