Robert H. Edwards's Blog: Great 20th century mysteries, page 3

June 19, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: the {M} conundrum

In a previous article on this platform, I proposed a strategy for discovering meaning in the text of the Voynich manuscript. I called it the {8am} strategy. My idea was to focus on the glyph string {8am}, which is the most frequent “word” in the v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. My proposed process was to test some alternative transliterations of the manuscript, and some target languages, and to see whether in one combination or another, {8am} would map to a recognizable word.

This research is ongoing. So far, it has yielded encouraging results for several transliterations, and for medieval Italian, represented by the OVI corpus, as the precursor language.

In these tests, I am dealing only with mappings of the glyphs {8}, {a} and {m}, which are common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript.

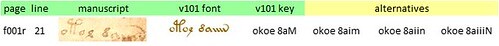

In a parallel research effort, as I reported in other articles, I have looked at mappings of the three right-justified sequences of glyphs on page f1r, the first page of the manuscript as currently bound. The hypothesis to be tested is that one or more of these sequences might represent a proper name. The third sequence is {okoe 8aM}. The glyph {M} is infrequent, and therefore presents a conundrum (of which, more below).

I have in mind to attempt mappings of the sequence {okoe 8aM} from various transliterations to a selection of medieval languages. The target languages include Albanian, Arabic, Bohemian, English, Finnish, French, Galician-Portuguese, German, Latin, Persian, Turkish and Welsh. This is a massive manual exercise and requires some objective criteria whereby one might prioritise the languages.

One such criterion is related to the rarity of the glyph {M}. In the v101 transliteration, {M} occurs just 45 times; its frequency is 0.1 percent; it is the 35th most frequent glyph. In most of the natural languages that I have examined, if we ignore punctuation, make no distinction between upper and lower case, and count only the letters with a frequency of at least 0.1 percent, the alphabet has between 24 and 30 letters.

If {M} is to map to any letter in a natural language, we have at least three possible strategies.

Alphabets with accents

If we retain all the glyphs in the v101 transliteration, then the alphabet of the target language must contain at least 35 letters. Mapping of the glyph {M} seems to require a language which has several accented letters in addition to the normal letters of the alphabet, or has at least 35 normal letters. However, as shown in the table below, of the languages that I have examined, the only one that meets this criterion is Ottoman Turkish.

Counts of letters in the alphabets of selected medieval languages. Author's analysis.

Upper and lower case

The Voynich manuscript shows no sign of a distinction between upper and lower case. That is to say, there are no pairs of glyphs in which one appears like a larger version of the other. This is so even we allow for differences in the shapes of upper and lower case letters, such as we see in the Latin script where “A” is not a magnified “a”.

However, to my mind we cannot exclude the idea that the Voynich producer provided the scribes with source documents that contained both upper and lower case letters; that he or she instructed them to map upper and lower case differently; even that the scribes did not know the precursor languages, and therefore could only map the shapes that they saw.

In that case, for each of the target languages (except Arabic, Persian and Turkish which have no upper and lower case), we could significantly increase the number of letters in the alphabet. Then, as shown in the table above, in several European languages we could find a mapping for a glyph as infrequent as {M}.

Combining groups of glyphs

Alternatively, or additionally, we could look for ways to move {M} upwards in the frequency rankings. The higher the ranking of {M}, the better its chance of mapping to a letter, even if an infrequent one, in some natural language.

One way to do so is to combine groups of visually similar glyphs, as I have done in many of my variants of the v101 transliteration.

For example, we can merge the v101 glyphs {6}, {7} and {&} with {8}; {3}, {5} and several variants with {2}; {j} with {g}; {u} with {f}; and {(} with {9}. This has the effect of moving the glyph {M} up to about 30th place. We can also redefine {m} as {iiN}, {n} as {iN}, and {M} as {iiiN}: in which case the sequence to be mapped becomes {okoe 8aiiiN}, and in place of {M}, we try to map {i} and {N} which are more frequent than {M}.

To my mind, all of these possibilities are worth a try. I will report in another article.

This research is ongoing. So far, it has yielded encouraging results for several transliterations, and for medieval Italian, represented by the OVI corpus, as the precursor language.

In these tests, I am dealing only with mappings of the glyphs {8}, {a} and {m}, which are common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript.

In a parallel research effort, as I reported in other articles, I have looked at mappings of the three right-justified sequences of glyphs on page f1r, the first page of the manuscript as currently bound. The hypothesis to be tested is that one or more of these sequences might represent a proper name. The third sequence is {okoe 8aM}. The glyph {M} is infrequent, and therefore presents a conundrum (of which, more below).

I have in mind to attempt mappings of the sequence {okoe 8aM} from various transliterations to a selection of medieval languages. The target languages include Albanian, Arabic, Bohemian, English, Finnish, French, Galician-Portuguese, German, Latin, Persian, Turkish and Welsh. This is a massive manual exercise and requires some objective criteria whereby one might prioritise the languages.

One such criterion is related to the rarity of the glyph {M}. In the v101 transliteration, {M} occurs just 45 times; its frequency is 0.1 percent; it is the 35th most frequent glyph. In most of the natural languages that I have examined, if we ignore punctuation, make no distinction between upper and lower case, and count only the letters with a frequency of at least 0.1 percent, the alphabet has between 24 and 30 letters.

If {M} is to map to any letter in a natural language, we have at least three possible strategies.

Alphabets with accents

If we retain all the glyphs in the v101 transliteration, then the alphabet of the target language must contain at least 35 letters. Mapping of the glyph {M} seems to require a language which has several accented letters in addition to the normal letters of the alphabet, or has at least 35 normal letters. However, as shown in the table below, of the languages that I have examined, the only one that meets this criterion is Ottoman Turkish.

Counts of letters in the alphabets of selected medieval languages. Author's analysis.

Upper and lower case

The Voynich manuscript shows no sign of a distinction between upper and lower case. That is to say, there are no pairs of glyphs in which one appears like a larger version of the other. This is so even we allow for differences in the shapes of upper and lower case letters, such as we see in the Latin script where “A” is not a magnified “a”.

However, to my mind we cannot exclude the idea that the Voynich producer provided the scribes with source documents that contained both upper and lower case letters; that he or she instructed them to map upper and lower case differently; even that the scribes did not know the precursor languages, and therefore could only map the shapes that they saw.

In that case, for each of the target languages (except Arabic, Persian and Turkish which have no upper and lower case), we could significantly increase the number of letters in the alphabet. Then, as shown in the table above, in several European languages we could find a mapping for a glyph as infrequent as {M}.

Combining groups of glyphs

Alternatively, or additionally, we could look for ways to move {M} upwards in the frequency rankings. The higher the ranking of {M}, the better its chance of mapping to a letter, even if an infrequent one, in some natural language.

One way to do so is to combine groups of visually similar glyphs, as I have done in many of my variants of the v101 transliteration.

For example, we can merge the v101 glyphs {6}, {7} and {&} with {8}; {3}, {5} and several variants with {2}; {j} with {g}; {u} with {f}; and {(} with {9}. This has the effect of moving the glyph {M} up to about 30th place. We can also redefine {m} as {iiN}, {n} as {iN}, and {M} as {iiiN}: in which case the sequence to be mapped becomes {okoe 8aiiiN}, and in place of {M}, we try to map {i} and {N} which are more frequent than {M}.

To my mind, all of these possibilities are worth a try. I will report in another article.

Published on June 19, 2024 12:05

•

Tags:

voynich

June 18, 2024

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: GhostBox Radio

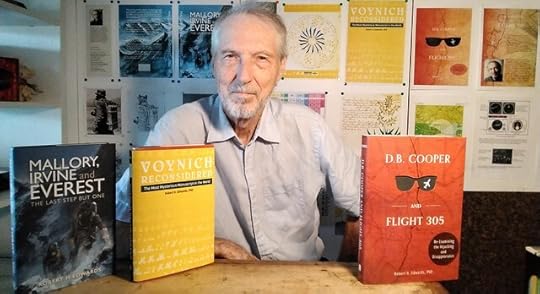

On June 17, 2024, GhostBox Radio in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis - St Paul) aired an episode on D.B. Cooper and Flight 305, with host Greg Bakun and myself.

AM950: https://am950radio.com/ghostbox-radio...

Youtube: https//www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEpa2aRz2v4

Image credit: GhostBox Radio.

In 1971, Minneapolis was the home of Northwest Airlines, and on November 24, 1971, was the base from which Northwest executive Paul Soderlind and his colleagues tracked the hijacking of Flight 305.

Subsequently, Soderlind and Dan Sowa conceptualised a search area in the vicinity of Ariel, Washington State. The FBI combed that area in the hope of finding traces of the hijacker’s passage. As history records, they found nothing.

AM950: https://am950radio.com/ghostbox-radio...

Youtube: https//www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEpa2aRz2v4

Image credit: GhostBox Radio.

In 1971, Minneapolis was the home of Northwest Airlines, and on November 24, 1971, was the base from which Northwest executive Paul Soderlind and his colleagues tracked the hijacking of Flight 305.

Subsequently, Soderlind and Dan Sowa conceptualised a search area in the vicinity of Ariel, Washington State. The FBI combed that area in the hope of finding traces of the hijacker’s passage. As history records, they found nothing.

Published on June 18, 2024 00:22

•

Tags:

dbcooper, fbi, ghostboxradio, gregbakun

June 16, 2024

Mallory, Irvine, Everest: review

I received this kind comment on Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One on Jake Norton’s Undefined Community:

This photograph, taken at Base Camp in 1922, is possibly the only image from the British expeditions to Everest in which Mallory and Finch both appear. (Left) George Mallory, (right) George Ingle Finch. Image credit: (probably) John Noel.

"Robert, I just wanted to say, after having recently purchased your new book, reading it I am intrigued by your perspective of the last climb by the group of climbers including Mallory & Irvine in 1924. If only Finch had been invited and had gone on that last fatal expedition perhaps things would have turned out less fatal? Anyway it is truly a fantastic book thank you!"I replied on the Undefined Community as follows:

"Indeed one must wonder what might have happened if George Finch had been a member of the 1924 expedition. In that case, surely he would have been designated as the oxygen officer, with Odell and possibly Irvine supporting. If Norton had planned or permitted even one climb with oxygen, and if it had been up to Norton, Finch would surely have been the leader of that climb. I hazard a guess that Finch would have chosen Odell as his climbing partner.

The agreed final plan in 1924, given the weather and the perceived availability of porters, was to make no climbs with oxygen. By this time Mallory was the climbing leader and as such, the principal decision-maker on the climbing parties. So we might conjecture that, even with Finch available, the first two climbing parties would have been the same: that is, Mallory and Bruce, followed by Norton and Somervell.

The third climb was not part of the plan: it was Mallory’s unexpected decision. Whether he would have chosen Finch over Irvine, I guess we have no way to know."

This photograph, taken at Base Camp in 1922, is possibly the only image from the British expeditions to Everest in which Mallory and Finch both appear. (Left) George Mallory, (right) George Ingle Finch. Image credit: (probably) John Noel.

June 15, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: the third name?

On the first page of the Voynich manuscript (folio f1r), there are three short strings of glyphs, in which one might suspect the representation of a proper name. In previous articles on this platform, I examined the first and second of these strings.

The third string, with its keyboard assignments in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

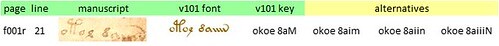

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 21 of the Voynich manuscript. Author’s analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

This sequence of glyphs is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the Voynich manuscript. We might therefore conjecture that it represents a proper name.

To my mind, the main uncertainty of interpretation is in the second “word”, in which there is a string that looks like {iii}, and what appears to be a final {N}. However, the string {8aiiiN} does not figure as a “word” in the Voynich manuscript; neither do the alternatives {8aim}, {8aiin}, {8aIn}, {8aIiN} or {8aiIN} On the basis of “word” counts, the most probable reading appears to be {okoe 8aM}.

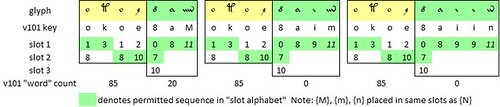

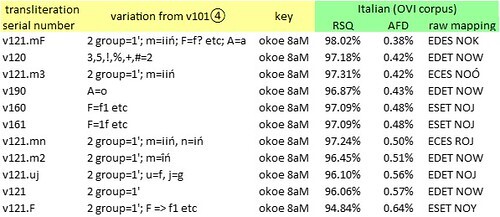

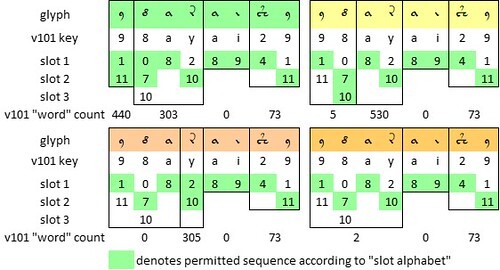

On this reading, both “words” exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript. Both conform to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimiliano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”.

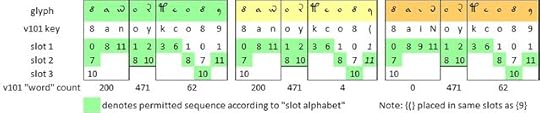

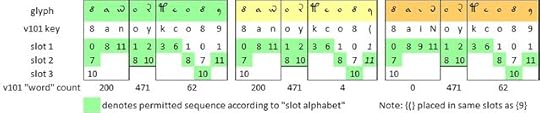

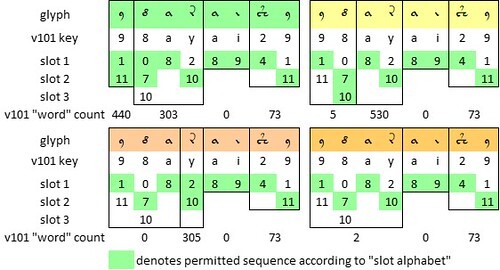

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 21: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s “slot alphabet”. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

As with the first and second glyph sequences on page f1r, I attempted mappings of the sequence {okoe 8aM} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to medieval Italian. My corpus of reference is OVI (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano).

In all of these exercises, I could see great uncertainty in the mapping of the glyph {M}, which (if it is a single glyph) occurs only 45 times in the whole of the v101 transliteration. Therefore, if it maps to any letter in Italian, it must be a relatively rare letter.

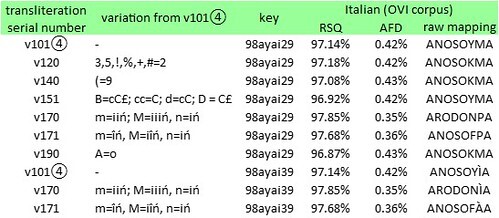

Below are selected mappings that, to my mind, seemed more plausible than others:

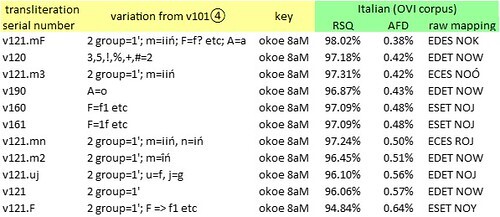

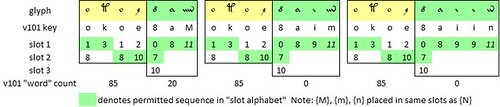

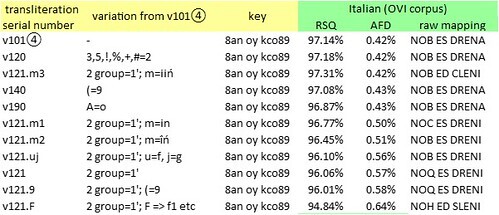

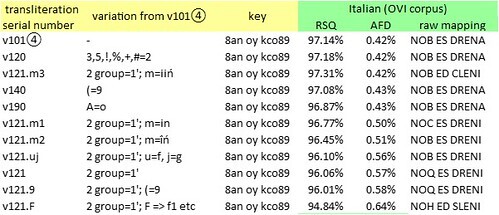

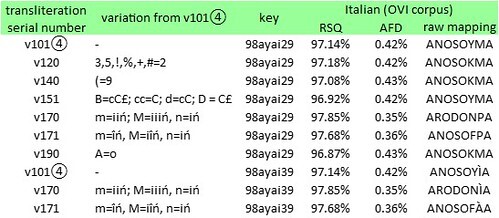

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {okoe 8aM} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

As far as the OVI corpus shows, only the text strings NOY and NOJ (both archaic forms of "we") are words in medieval Italian.

As with the first and second strings on page f1r, I can imagine other possible mappings, including the following:

The third string, with its keyboard assignments in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 21 of the Voynich manuscript. Author’s analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

This sequence of glyphs is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the Voynich manuscript. We might therefore conjecture that it represents a proper name.

To my mind, the main uncertainty of interpretation is in the second “word”, in which there is a string that looks like {iii}, and what appears to be a final {N}. However, the string {8aiiiN} does not figure as a “word” in the Voynich manuscript; neither do the alternatives {8aim}, {8aiin}, {8aIn}, {8aIiN} or {8aiIN} On the basis of “word” counts, the most probable reading appears to be {okoe 8aM}.

On this reading, both “words” exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript. Both conform to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimiliano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 21: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s “slot alphabet”. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

As with the first and second glyph sequences on page f1r, I attempted mappings of the sequence {okoe 8aM} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to medieval Italian. My corpus of reference is OVI (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano).

In all of these exercises, I could see great uncertainty in the mapping of the glyph {M}, which (if it is a single glyph) occurs only 45 times in the whole of the v101 transliteration. Therefore, if it maps to any letter in Italian, it must be a relatively rare letter.

Below are selected mappings that, to my mind, seemed more plausible than others:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {okoe 8aM} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

As far as the OVI corpus shows, only the text strings NOY and NOJ (both archaic forms of "we") are words in medieval Italian.

As with the first and second strings on page f1r, I can imagine other possible mappings, including the following:

• mappings based on other transliterations: for example, with the initial {o} treated as a wild card, or as an abbreviation sign

• a flexible mapping of the glyph {M), which has the right frequency to map to any of the Italian letters É, Ù, X, or K, or (less probably) the rare Y, J, Ó or W

• or a re-interpretation of the glyph {M} as {im} or {iin} or {iiiN}; and in turn, we can create permutations with {ii} re-interpreted as {I}

• re-ordering of the letters within the text strings: for example, we could re-order EDES as SEDE (“seats”, or “sees” in the sense of seats of the church); and NOK as KON (archaic "with")

• and of course, mappings based on other languages than Italian.

June 14, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: the second name?

In a previous article on this platform, I examined the first of three short strings of glyphs on the first page of the Voynich manuscript. Each of these strings, unlike most of the Voynich text, is approximately right-justified. My idea, inspired by a recent debate on the voynich.ninja forum, was to see whether, among these strings, one might detect a proper name.

The second string, and its representation in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 10 of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

As with the first string, this sequence is open to some differences of interpretation. The v101 glyph {n} could be read as {iN}; and the glyph {(} looks like a hastily drawn {9}. If we accept that the first “word” is {8an}, and allow the last “word” to read {kco89}, all three “words” in the sequence are common in the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, the most probable reading is {8an oy kco89}. But the three "words" in this sequence occur nowhere else in the manuscript.

All three “words” confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimilano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera's work expanded and quantified the earlier study of Mary D'Imperio on rules which she had called the "five states".

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 10: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s alphabet. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

I attempted mappings of the sequence {8an oy kco89} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to some potential precursor languages. As before, I used frequency analysis as a tool for matching glyphs with letters (recognising that there should be some flexibility in the matching). As a priority language, again I started with medieval Italian, for the reasons that I outlined in the previous article.

Below are selected mappings that seemed to yield pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {8an oy kco89} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

Of these text strings, only ES (a form of “is”) and ED (“and”) are words in medieval Italian.

To my mind, other possible mappings include the following:

The second string, and its representation in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 10 of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

As with the first string, this sequence is open to some differences of interpretation. The v101 glyph {n} could be read as {iN}; and the glyph {(} looks like a hastily drawn {9}. If we accept that the first “word” is {8an}, and allow the last “word” to read {kco89}, all three “words” in the sequence are common in the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, the most probable reading is {8an oy kco89}. But the three "words" in this sequence occur nowhere else in the manuscript.

All three “words” confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimilano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera's work expanded and quantified the earlier study of Mary D'Imperio on rules which she had called the "five states".

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 10: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s alphabet. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

I attempted mappings of the sequence {8an oy kco89} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to some potential precursor languages. As before, I used frequency analysis as a tool for matching glyphs with letters (recognising that there should be some flexibility in the matching). As a priority language, again I started with medieval Italian, for the reasons that I outlined in the previous article.

Below are selected mappings that seemed to yield pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {8an oy kco89} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

Of these text strings, only ES (a form of “is”) and ED (“and”) are words in medieval Italian.

To my mind, other possible mappings include the following:

• mappings based on other transliterations: for example, with the final {(} or {9} treated as wild cards, or as abbreviation signs

• flexible mapping of the glyph {k), which has a frequency of 4.2 percent in the v101 transliteration, and could plausibly map to C: in which case {kco89} could map to CRENA ("notch" or "furrow")

• re-ordering of the letters within the strings: for example, we could re-order NOB as BON (“good”), a very common word in medieval Italian; ES as SE (“if”), an extremely common word; and CRENA as CARNE ("meat" or "flesh")

• mappings based on other languages.

June 10, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: the author’s name?

On the voynich.ninja forum, I read a proposal that somewhere on the first page of the Voynich manuscript, we might detect the name of the author.

There is no doubt that on page f1r (that is, folio 1 recto), there are three short strings of glyphs which, unlike most of the text, are approximately right-justified. They are as follows:

Three right-justified strings of glyphs on page f1r of the Voynich manuscript; and their representations in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. Author's analysis. Image credits: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

We should observe that f1r is not necessarily the original first page. There is evidence that the manuscript has been re-bound, and that the pages are not in their original order. In the upper right corner of page f1r, we see the Arabic numeral 1 (which gives the page its modern numbering); but we are not obliged to assume that it was there when the manuscript was written.

However, if f1r is indeed the original first page, it seems to me a reasonable hypothesis that the three right-justified strings of glyphs have some special significance. We might conjecture that they represent names: for example, of patrons, producers, authors, or scribes. We have no way of knowing how many people were involved in the conception of the manuscript. But Dr Lisa Fagin Davis has identified five scribes: of whom Scribes 1, 2 and 3 contributed 188 of the 227 pages.

{98ayai29}

With that preamble: I propose here to examine the first string of glyphs, on line 6, represented in the v101 transliteration by {98ayai29}. Referring to the manuscript as it appears on the website of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I could also read this string as {98ayai39} or {98ayai59}, although the glyphs {3} and {5} are much less common than {2}. I could also accept the possibility that the glyph {2} is a {1} with an accent of unknown significance, and if so, I could read the string as {98ayai1’9}.

This glyph string has some unusual properties.

Firstly, the string is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the manuscript: neither as a “word”, nor as a string within a “word”. It is, in linguists’ terminology, a hapax legomenon. That might permit us to suspect that it represents a proper name.

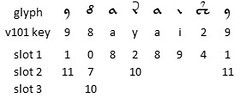

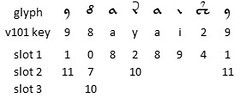

Secondly, the string does not confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words”, which Mary D’Imperio called the “five states”, and which Massimilano Zattera, in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera demonstrated that over 98 percent of the “words” in the Voynich manuscript conform to rules of this nature, or can be disaggregated into chunks which so conform. But this string does not. Below are the glyphs which make up the string, and the permitted slots which, according to Zattera, they may occupy.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 6: glyphs and permitted Zattera "slots”. Author’s analysis.

We can see that, even allowing for the flexibility of the glyphs {8}, {9} and {y}, we cannot allocate glyphs to slots in such a way that each glyph is followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

We therefore have to conjecture that the string is not a “word”, but may consist of several “words”, with the word breaks omitted or suppressed. This conjecture is easy to test. We can parse the string {98ayai29} in various ways. For each parsing, we can see whether it produces “words” that exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript, and that conform to the slot sequence.

Below is a summary of the tests that I have conducted so far.

Four ways of parsing the v101 glyph string {98ayai29}; the permitted slots in Zattera's "slot alphabet"; and the “word” counts of each parsed segment in the v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

From these results, it seems to me that, if the Voynich scribes intended the string {98ayai29} to conform to the slot sequence, we might infer the following:

Thus, to my mind, if the string is part of the Voynich vocabulary, the most plausible parsing is {9 8ay ai 29}. However, that would still leave {ai} as a non-existent “word”; and we cannot break it further, since {i} never occurs as a single-glyph “word”.

A proper name?

Alternatively, we might conjecture that the string {98ayai29} is not part of the Voynich vocabulary: that is to say, it is not a normal word in the (presumed) precursor language or languages of the manuscript. For the Voynich scribes, it might have been a proper name, or even a foreign word.

In previous articles on this platform, I have advanced the hypothesis that the producer of the Voynich manuscript provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages; a set of mappings from letters to glyphs; and also a set of rules, applied after mapping, for re-ordering the glyphs within “words”. To my mind, these are plausible mechanisms to explain the sequencing of glyphs within “words”, which to my knowledge, does not occur in any natural language.

We might now imagine the scribes faced with an unusual word (that is, either a proper name, or a word from a language other than the primary precursor languages). In such a case, perhaps they would not, or could not, apply their normal rules. For example, they might apply the mapping from letters to glyphs, but omit the re-ordering of glyphs.

In any case, we have nothing to lose by attempting a mapping from the string {98ayai29} to some potential source languages.

In any such mapping, I prefer to avoid or at least to minimise the element of subjectivity, and to examine a range of possible languages, as well as a range of possible transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. For each language and for each transliteration, frequency analysis can be a guide as to how we map a glyph to a letter.

I started with medieval Italian, if only because in previous work, this language had shown promise as a possible precursor of the Voynich text. For example, as I reported in a previous article, several of my variant transliterations yielded mappings of the glyph string {8am} to the Italian words CON (“with”) or alternatively DIO (“God”). Against Italian, it might be argued that if the main text were in Italian, then the right-justified strings on page f1r could be in another language. Anyway, I thought it worth a try.

Below are selected mappings that came closest to yielding pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {98ayai29} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

I have to admit that none of these text strings is, to my knowledge, a word or a proper name in medieval Italian. But it seems to me that there are possibilities to be explored, along the following lines:

I invite any readers who may be interested to explore this approach. If any reader should favor a specific language as the precursor of the glyph string {98ayai29}, and if I have a sufficiently large corpus of text in that language, I will be happy to supply a proposed mapping from glyphs to letters.

There is no doubt that on page f1r (that is, folio 1 recto), there are three short strings of glyphs which, unlike most of the text, are approximately right-justified. They are as follows:

Three right-justified strings of glyphs on page f1r of the Voynich manuscript; and their representations in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. Author's analysis. Image credits: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

We should observe that f1r is not necessarily the original first page. There is evidence that the manuscript has been re-bound, and that the pages are not in their original order. In the upper right corner of page f1r, we see the Arabic numeral 1 (which gives the page its modern numbering); but we are not obliged to assume that it was there when the manuscript was written.

However, if f1r is indeed the original first page, it seems to me a reasonable hypothesis that the three right-justified strings of glyphs have some special significance. We might conjecture that they represent names: for example, of patrons, producers, authors, or scribes. We have no way of knowing how many people were involved in the conception of the manuscript. But Dr Lisa Fagin Davis has identified five scribes: of whom Scribes 1, 2 and 3 contributed 188 of the 227 pages.

{98ayai29}

With that preamble: I propose here to examine the first string of glyphs, on line 6, represented in the v101 transliteration by {98ayai29}. Referring to the manuscript as it appears on the website of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I could also read this string as {98ayai39} or {98ayai59}, although the glyphs {3} and {5} are much less common than {2}. I could also accept the possibility that the glyph {2} is a {1} with an accent of unknown significance, and if so, I could read the string as {98ayai1’9}.

This glyph string has some unusual properties.

Firstly, the string is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the manuscript: neither as a “word”, nor as a string within a “word”. It is, in linguists’ terminology, a hapax legomenon. That might permit us to suspect that it represents a proper name.

Secondly, the string does not confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words”, which Mary D’Imperio called the “five states”, and which Massimilano Zattera, in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera demonstrated that over 98 percent of the “words” in the Voynich manuscript conform to rules of this nature, or can be disaggregated into chunks which so conform. But this string does not. Below are the glyphs which make up the string, and the permitted slots which, according to Zattera, they may occupy.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 6: glyphs and permitted Zattera "slots”. Author’s analysis.

We can see that, even allowing for the flexibility of the glyphs {8}, {9} and {y}, we cannot allocate glyphs to slots in such a way that each glyph is followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

We therefore have to conjecture that the string is not a “word”, but may consist of several “words”, with the word breaks omitted or suppressed. This conjecture is easy to test. We can parse the string {98ayai29} in various ways. For each parsing, we can see whether it produces “words” that exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript, and that conform to the slot sequence.

Below is a summary of the tests that I have conducted so far.

Four ways of parsing the v101 glyph string {98ayai29}; the permitted slots in Zattera's "slot alphabet"; and the “word” counts of each parsed segment in the v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

From these results, it seems to me that, if the Voynich scribes intended the string {98ayai29} to conform to the slot sequence, we might infer the following:

• the final {29} must be a separate “word”;Here we may note that the “word” {8ay} is part of a family of common Voynich “words” which includes the ubiquitous [8am} as well as {8an}, {8aM} and {8ae}.

• as for the rest of the string, the parsing which yields the most real “words” has {9} as a single-glyph “word”, and {8ay} as another “word”.

Thus, to my mind, if the string is part of the Voynich vocabulary, the most plausible parsing is {9 8ay ai 29}. However, that would still leave {ai} as a non-existent “word”; and we cannot break it further, since {i} never occurs as a single-glyph “word”.

A proper name?

Alternatively, we might conjecture that the string {98ayai29} is not part of the Voynich vocabulary: that is to say, it is not a normal word in the (presumed) precursor language or languages of the manuscript. For the Voynich scribes, it might have been a proper name, or even a foreign word.

In previous articles on this platform, I have advanced the hypothesis that the producer of the Voynich manuscript provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages; a set of mappings from letters to glyphs; and also a set of rules, applied after mapping, for re-ordering the glyphs within “words”. To my mind, these are plausible mechanisms to explain the sequencing of glyphs within “words”, which to my knowledge, does not occur in any natural language.

We might now imagine the scribes faced with an unusual word (that is, either a proper name, or a word from a language other than the primary precursor languages). In such a case, perhaps they would not, or could not, apply their normal rules. For example, they might apply the mapping from letters to glyphs, but omit the re-ordering of glyphs.

In any case, we have nothing to lose by attempting a mapping from the string {98ayai29} to some potential source languages.

In any such mapping, I prefer to avoid or at least to minimise the element of subjectivity, and to examine a range of possible languages, as well as a range of possible transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. For each language and for each transliteration, frequency analysis can be a guide as to how we map a glyph to a letter.

I started with medieval Italian, if only because in previous work, this language had shown promise as a possible precursor of the Voynich text. For example, as I reported in a previous article, several of my variant transliterations yielded mappings of the glyph string {8am} to the Italian words CON (“with”) or alternatively DIO (“God”). Against Italian, it might be argued that if the main text were in Italian, then the right-justified strings on page f1r could be in another language. Anyway, I thought it worth a try.

Below are selected mappings that came closest to yielding pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {98ayai29} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

I have to admit that none of these text strings is, to my knowledge, a word or a proper name in medieval Italian. But it seems to me that there are possibilities to be explored, along the following lines:

• other variants of the transliteration of the Voynich manuscript (which will have slightly different glyph frequencies, therefore slightly different rankings of the glyphs, therefore slightly different mappings between glyphs and the Italian letters)Next steps

• parsing the glyph string as implied by the “slot alphabet”; for example, in the v151 transliteration, the parsed sequence (9 8ay ai 29} maps to A NOS OY MA; and we could consider re-ordering NOS as SON, and so on;

• and of course, there are other languages to be tried: as I have suggested in other articles, I am inclined to give priority to languages used in or near medieval Italy, for example, Latin, French or Albanian.

I invite any readers who may be interested to explore this approach. If any reader should favor a specific language as the precursor of the glyph string {98ayai29}, and if I have a sufficiently large corpus of text in that language, I will be happy to supply a proposed mapping from glyphs to letters.

June 2, 2024

Great 20th Century Mysteries

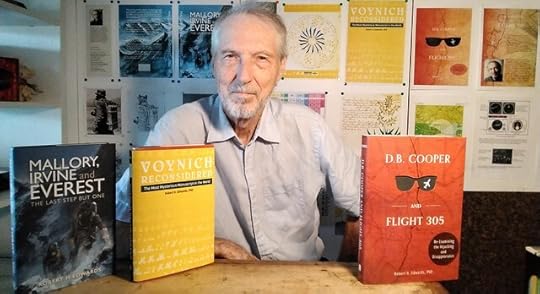

Author Bob Edwards and three "Great 20th Century Mysteries":

Image credit: author. Cover credits: Schiffer (D. B. Cooper and Flight 305, Voynich Reconsidered); Pen And Sword and Balázs Petheő (Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One)

* D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer, 24 November 2021);

* Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword, 4 April 2024);

* Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer, August 2024).

Image credit: author. Cover credits: Schiffer (D. B. Cooper and Flight 305, Voynich Reconsidered); Pen And Sword and Balázs Petheő (Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One)

Published on June 02, 2024 05:29

•

Tags:

balázs-petheő, dbcooper, everest, irvine, mallory, penandsword, schiffer, voynich

June 1, 2024

Mallory, Irvine, Everest: reviews and comments

Some recent reviews and comments on Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, 2024, https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Mallo...

Image credit: Pen And Sword. Cover painting: Balázs Petheő.

from Judy Glaser: "Just finished this book. Really liked the format, attention to details, and writing style."

https://www.facebook.com/groups/11837...

from Bob George: "Just listened to the [WanderLearn] video Bob and I now won't hesitate to purchase the book. Well done Sir and hats off to you."

https://www.facebook.com/groups/11837...

from KI Double: "I think they made it bob. Awesome video also!"

https://www.facebook.com/groups/69158...

[Video podcast with Francis Tapon of WanderLearn at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_alNn... ]

Image credit: Pen And Sword. Cover painting: Balázs Petheő.

Published on June 01, 2024 22:04

•

Tags:

balázs-petheő, everest, irvine, mallory

Mallory, Irvine, Everest: WanderLearn

Here is my video podcast with Francis Tapon of the Wanderlearn YouTube channel, discussing Mallory, Irvine and Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, 2024).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_alNn...

This is a photo published by Merton College, Oxford University, depicting the position of Mallory and Irvine at 12.50pm on June 8, 1924. The same image appeared in John Noel's book "Through Tibet to Everest", with slightly different annotations. Image credit: John Noel; author of annotations unknown.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_alNn...

This is a photo published by Merton College, Oxford University, depicting the position of Mallory and Irvine at 12.50pm on June 8, 1924. The same image appeared in John Noel's book "Through Tibet to Everest", with slightly different annotations. Image credit: John Noel; author of annotations unknown.

Published on June 01, 2024 10:09

•

Tags:

everest, francis-tapon, irvine, john-noel, mallory, noel-odell, wanderlearn

May 25, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: wild cards

In the course of my ongoing research on the Voynich manuscript, I selected some of the most common “words” in the manuscript - "words" like {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}. I mapped them these "words" to text strings in selected medieval languages. As a basis for the mappings, I used frequency analysis - that is, the juxtaposition of glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. My objective was to see whether any of the resulting text strings were common words in the target languages.

My working assumptions, as I mentioned in those articles, included the following:

However, frequency analysis would not work very well on abbreviated text, for example on abbreviation symbols for prefixes, suffixes or whole words. As Adriano Cappelli illustrated in his landmark work Lexicon Abbreviaturarum, medieval scribes used such symbols routinely and extensively, at least in Latin and in Italian. I therefore saw a need to allow for what we might call wild cards.

(From here on, I will refer to the glyphs by their keyboard assignments in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, or in my variants of that transliteration.)

For example, the glyph {9}, in the initial and final position, is far too frequent to correspond to any single prefix, suffix or case ending in Latin or Italian. In these positions, it might represent an abbreviation sign. As Cappelli showed, and as many Voynich researchers have observed, there were medieval abbreviation symbols that resembled the number 9. Therefore, if we suspect that the precursor documents were abbreviated, it might be advisable to use a mapping in which the initial and final {9} are not assigned to any specific letter. That is, we could designate the initial and final {9} as wild cards.

Wild cards

To test this hypothesis, it seemed to me that we would need additional transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, in which, for {9} and certain other glyphs, we made a distinction between the glyphs in the initial, final and other positions.

I therefore developed several variant transliterations incorporating glyphs as wild cards, not mapped to any specific letter in a natural language, as follows:

My first test was on medieval Italian, which in other mappings had shown promise as a potential precursor language of the Voynich manuscript. As a corpus of reference, I used OVI (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano), which consists of texts written prior to the year 1400, and is the largest online database of its kind. As of April 4, 2024, it contained 3,512 texts, with 30,443,280 words.

As a test case I selected the “word” {8am}, which is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. My thinking is that if {8am} maps to a real word in any natural language, it is worthwhile to proceed with other Voynich “words”; but if not, we have probably chosen the wrong precursor languages, or the wrong transliteration of the Voynich manuscript.

My procedure for each transliteration, in essence, was as follows:

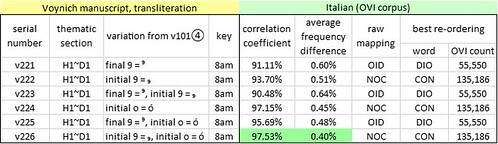

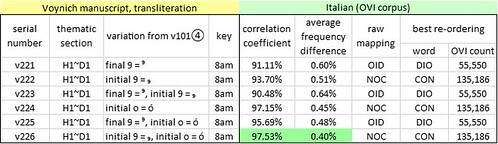

The ten most frequent letters in medieval Italian (as represented by the OVI corpus); and the ten most frequent glyphs in the v221 through v226 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

The resulting mapping of the “word” {8am} to Italian is summarised as follows:

Mappings of the Voynich "word" {8am} to medieval Italian, on the basis of the Italian letter frequencies and the glyph frequencies in the v221 through v226 transliterations. Author's analysis.

We see that in three of these transliterations, the “word” {8am} can be mapped to the Italian word “CON” (in English, “with”); and in three transliterations, to the Italian word “DIO” (“God”). In both cases the raw mapping has to be re-ordered, with the glyphs read from right to left. Here we may suspect a simple process of encipherment, in which the Voynich producer instructed the scribes to write from left to right, but to reverse the order of the glyphs in each “word”.

Next steps

This process can and should be applied to other common Voynich “words”, such as {oe}, {1oe) and {1c9}. In some cases, some of the glyphs may have to be treated as wild cards: for example {oe) may become {óe}, and {1c9} may become {1c⁹}.

What I hope this approach may demonstrate is that someone with a good knowledge of any candidate language, and access to a suitable corpus of reference, can apply frequency analysis to a mapping of any word, line or page of the Voynich manuscript. I think that in any such mapping, it will be necessary to designate some Voynich glyphs as “wild cards”, but a limited number, and in specific positions within the “word”.

My working assumptions, as I mentioned in those articles, included the following:

• that the producer of the Voynich manuscript had provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages;A consequence of these assumptions was that, whether the producer and the scribes knew it or not, the frequencies of the Voynich glyphs would match the frequencies of the letters in the source documents. Therefore, frequency analysis could be a tool with which to map Voynich “words” to words in real languages. If that worked, it could lead to at least a partial mapping of whole lines or pages from the Voynich text.

• that those languages were more likely to be European than not, and more likely to be medieval than modern;

• that the producer had instructed the scribes to map from letters in the original script (for example, Latin, Greek, Glagolitic or Cyrillic) to what we now call Voynich glyphs;

• and that the mapping was, at least for the most part, one-to-one; that is, in general a given letter would correspond uniquely to a Voynich glyph.

However, frequency analysis would not work very well on abbreviated text, for example on abbreviation symbols for prefixes, suffixes or whole words. As Adriano Cappelli illustrated in his landmark work Lexicon Abbreviaturarum, medieval scribes used such symbols routinely and extensively, at least in Latin and in Italian. I therefore saw a need to allow for what we might call wild cards.

(From here on, I will refer to the glyphs by their keyboard assignments in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, or in my variants of that transliteration.)

For example, the glyph {9}, in the initial and final position, is far too frequent to correspond to any single prefix, suffix or case ending in Latin or Italian. In these positions, it might represent an abbreviation sign. As Cappelli showed, and as many Voynich researchers have observed, there were medieval abbreviation symbols that resembled the number 9. Therefore, if we suspect that the precursor documents were abbreviated, it might be advisable to use a mapping in which the initial and final {9} are not assigned to any specific letter. That is, we could designate the initial and final {9} as wild cards.

Wild cards

To test this hypothesis, it seemed to me that we would need additional transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, in which, for {9} and certain other glyphs, we made a distinction between the glyphs in the initial, final and other positions.

I therefore developed several variant transliterations incorporating glyphs as wild cards, not mapped to any specific letter in a natural language, as follows:

• v221: a final {9} was represented by the Unicode symbol ⁹ (superscript 9); in all other positions remaining as {9}Corpora of reference

• v222: an initial {9} was represented by the Unicode symbol ₉ (subscript 9); in all other positions remaining as {9}

• v223: an initial {9} was represented by ₉; a final {9} represented by ⁹; in all other positions remaining as {9}.

• v224: an initial {o} was represented by the Unicode symbol ó (o with acute accent); in all other positions remaining as {o}.

• v225: an initial {o} was represented by ó (o with acute accent); a final 9 was represented by ⁹; in all other positions, {9} and {o} were unchanged

• v226: an initial {o} was represented by ó (o with acute accent); an initial 9 was represented by ₉; in all other positions, {9} and {o} were unchanged.

My first test was on medieval Italian, which in other mappings had shown promise as a potential precursor language of the Voynich manuscript. As a corpus of reference, I used OVI (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano), which consists of texts written prior to the year 1400, and is the largest online database of its kind. As of April 4, 2024, it contained 3,512 texts, with 30,443,280 words.

As a test case I selected the “word” {8am}, which is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. My thinking is that if {8am} maps to a real word in any natural language, it is worthwhile to proceed with other Voynich “words”; but if not, we have probably chosen the wrong precursor languages, or the wrong transliteration of the Voynich manuscript.

My procedure for each transliteration, in essence, was as follows:

• to calculate the frequencies of the glyphs (excluding the “wild card” glyphs)The matching of the top ten letter frequencies with the top ten glyph frequencies is summarised as follows:

• to match the rankings of the glyphs with the rankings of the letters in Italian (for example, the most frequent glyph matched the most frequent letter, and so on)

• to map the “word” {8am} to the corresponding text string in Italian

• to search the OVI corpus for occurrences of that text string as a word

• if no or few such occurrences were found: to search the OVI corpus for occurrences of the text string with letters re-ordered (this step being inspired by the work of Mary D’Imperio and Massimiliano Zattera on the apparent rules for sequencing glyphs within Voynich “words”).

The ten most frequent letters in medieval Italian (as represented by the OVI corpus); and the ten most frequent glyphs in the v221 through v226 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

The resulting mapping of the “word” {8am} to Italian is summarised as follows:

Mappings of the Voynich "word" {8am} to medieval Italian, on the basis of the Italian letter frequencies and the glyph frequencies in the v221 through v226 transliterations. Author's analysis.

We see that in three of these transliterations, the “word” {8am} can be mapped to the Italian word “CON” (in English, “with”); and in three transliterations, to the Italian word “DIO” (“God”). In both cases the raw mapping has to be re-ordered, with the glyphs read from right to left. Here we may suspect a simple process of encipherment, in which the Voynich producer instructed the scribes to write from left to right, but to reverse the order of the glyphs in each “word”.

Next steps

This process can and should be applied to other common Voynich “words”, such as {oe}, {1oe) and {1c9}. In some cases, some of the glyphs may have to be treated as wild cards: for example {oe) may become {óe}, and {1c9} may become {1c⁹}.

What I hope this approach may demonstrate is that someone with a good knowledge of any candidate language, and access to a suitable corpus of reference, can apply frequency analysis to a mapping of any word, line or page of the Voynich manuscript. I think that in any such mapping, it will be necessary to designate some Voynich glyphs as “wild cards”, but a limited number, and in specific positions within the “word”.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers