Voynich Reconsidered: the second name?

In a previous article on this platform, I examined the first of three short strings of glyphs on the first page of the Voynich manuscript. Each of these strings, unlike most of the Voynich text, is approximately right-justified. My idea, inspired by a recent debate on the voynich.ninja forum, was to see whether, among these strings, one might detect a proper name.

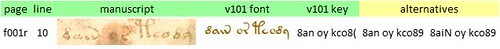

The second string, and its representation in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 10 of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

As with the first string, this sequence is open to some differences of interpretation. The v101 glyph {n} could be read as {iN}; and the glyph {(} looks like a hastily drawn {9}. If we accept that the first “word” is {8an}, and allow the last “word” to read {kco89}, all three “words” in the sequence are common in the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, the most probable reading is {8an oy kco89}. But the three "words" in this sequence occur nowhere else in the manuscript.

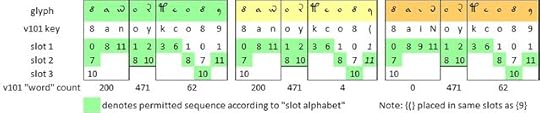

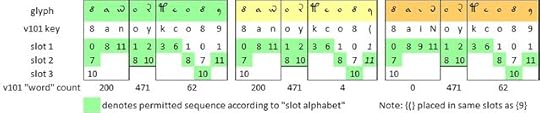

All three “words” confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimilano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera's work expanded and quantified the earlier study of Mary D'Imperio on rules which she had called the "five states".

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 10: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s alphabet. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

I attempted mappings of the sequence {8an oy kco89} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to some potential precursor languages. As before, I used frequency analysis as a tool for matching glyphs with letters (recognising that there should be some flexibility in the matching). As a priority language, again I started with medieval Italian, for the reasons that I outlined in the previous article.

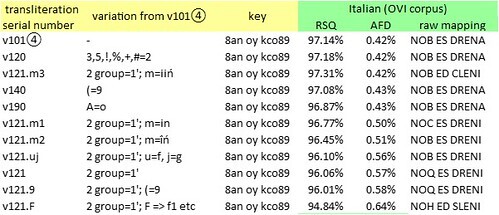

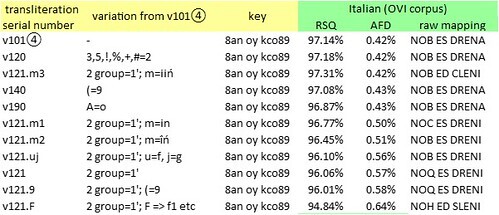

Below are selected mappings that seemed to yield pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {8an oy kco89} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

Of these text strings, only ES (a form of “is”) and ED (“and”) are words in medieval Italian.

To my mind, other possible mappings include the following:

The second string, and its representation in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration, is as follows:

A right-justified sequence of glyphs on page f1r, line 10 of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

As with the first string, this sequence is open to some differences of interpretation. The v101 glyph {n} could be read as {iN}; and the glyph {(} looks like a hastily drawn {9}. If we accept that the first “word” is {8an}, and allow the last “word” to read {kco89}, all three “words” in the sequence are common in the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, the most probable reading is {8an oy kco89}. But the three "words" in this sequence occur nowhere else in the manuscript.

All three “words” confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words” which Massimilano Zattera has called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera's work expanded and quantified the earlier study of Mary D'Imperio on rules which she had called the "five states".

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 10: three interpretations of the glyphs, and the permitted "slots” in Zattera’s alphabet. Author’s analysis.

Mappings

I attempted mappings of the sequence {8an oy kco89} from various alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, to some potential precursor languages. As before, I used frequency analysis as a tool for matching glyphs with letters (recognising that there should be some flexibility in the matching). As a priority language, again I started with medieval Italian, for the reasons that I outlined in the previous article.

Below are selected mappings that seemed to yield pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {8an oy kco89} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

Of these text strings, only ES (a form of “is”) and ED (“and”) are words in medieval Italian.

To my mind, other possible mappings include the following:

• mappings based on other transliterations: for example, with the final {(} or {9} treated as wild cards, or as abbreviation signs

• flexible mapping of the glyph {k), which has a frequency of 4.2 percent in the v101 transliteration, and could plausibly map to C: in which case {kco89} could map to CRENA ("notch" or "furrow")

• re-ordering of the letters within the strings: for example, we could re-order NOB as BON (“good”), a very common word in medieval Italian; ES as SE (“if”), an extremely common word; and CRENA as CARNE ("meat" or "flesh")

• mappings based on other languages.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers