Robert H. Edwards's Blog: Great 20th century mysteries, page 7

February 11, 2024

Voynich Reconsidered: abjad languages

The Voynich manuscript contains, by my count, 158,943 glyphs. They are arranged in 40,699 strings which have the appearance of words. Thus the average length of a Voynich "word" is 3.91 glyphs. This is relatively short by comparison with the average length of words in most European languages.

The issue therefore arises as to whether the text of the Voynich manuscript is derived from an abjad language, in which the long vowels are written but the short vowels usually are not. The abjad languages typically have shorter words than fully phonetic languages (as are most European languages). Therefore, as a precursor of Voynich, any abjad language looks promising.

Examples of abjad languages include Arabic, Hebrew, Ottoman Turkish and Persian.

Recently I had the opportunity to correspond with Dr Jiří Milička of the Faculty of Comparative Linguistics at Charles University in Czechia. In my research on Arabic as a possible precursor language of the Voynich manuscript, I drew upon Dr Jiří Milička’s article “Average word length from the diachronic perspective: the case of Arabic”.

Our correspondence prompted me to set down some thoughts about abjad languages and Voynich.

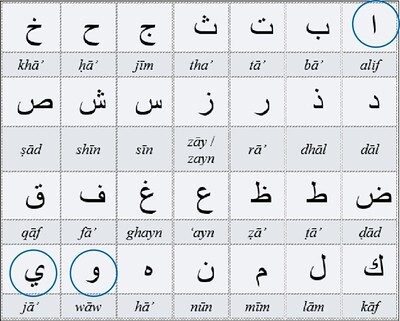

The Arabic alphabet, with the three long vowels circled. Image credit: Mohamed Jaafari

If we could identify an abjad language which underlay the Voynich manuscript, we could probably narrow down the era in which it was written. As Dr Milička has demonstrated, Arabic words have gradually become longer over time, from the eighth century to the present day. The average length of an Arabic word in the fifteenth century was 4.12 letters; in the twentieth century, 4.30 letters.

I can think of two downsides of abjad languages, as I have written in my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024).

One is that in modern times, the major abjad languages - at least Arabic, Hebrew and Persian - are written from right to left. To the best of my knowledge, that was so in medieval times. The text of the Voynich manuscript, when it occurs in horizontal lines, is left-justified, and gives the overwhelming impression of having been written from left to right. That does not exclude precursor documents written from right to left; but the transposition would have vastly increased the workload for the scribes, and therefore the cost to the producer.

The other danger with the hypothesis of an abjad language is that any short string of letters has a sporting chance of making a word. In 2016, Bradley Hauer and Grzegorz Kondrak proposed Hebrew as the precursor language, and suggested a Hebrew translation of the first line of page f1r. I tested their mapping against longer chunks of Voynich text, and it did not produce sensible narrative.

Having spent some years in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, I am familiar with the Arabic alphabet. I have tested various correspondences between Voynich glyph frequencies and Arabic letter frequencies, and they yielded some short Arabic words, but they did not work for strings longer than three glyphs.

Likewise with Persian: the mappings produced some Persian words from strings up to three glyphs, but broke down at the four-glyph level.

In another post on this platform, I have proposed that in any proposed mapping from Voynich glyphs to a natural language, one needs to work with a sufficiently large chunk of Voynich text (at least a paragraph, or a page, or longer). In the case of abjad languages, I think it would be doubly important to work with reasonably long extracts from the Voynich text, in order to avoid producing apparently meaningful words by chance.

The issue therefore arises as to whether the text of the Voynich manuscript is derived from an abjad language, in which the long vowels are written but the short vowels usually are not. The abjad languages typically have shorter words than fully phonetic languages (as are most European languages). Therefore, as a precursor of Voynich, any abjad language looks promising.

Examples of abjad languages include Arabic, Hebrew, Ottoman Turkish and Persian.

Recently I had the opportunity to correspond with Dr Jiří Milička of the Faculty of Comparative Linguistics at Charles University in Czechia. In my research on Arabic as a possible precursor language of the Voynich manuscript, I drew upon Dr Jiří Milička’s article “Average word length from the diachronic perspective: the case of Arabic”.

Our correspondence prompted me to set down some thoughts about abjad languages and Voynich.

The Arabic alphabet, with the three long vowels circled. Image credit: Mohamed Jaafari

If we could identify an abjad language which underlay the Voynich manuscript, we could probably narrow down the era in which it was written. As Dr Milička has demonstrated, Arabic words have gradually become longer over time, from the eighth century to the present day. The average length of an Arabic word in the fifteenth century was 4.12 letters; in the twentieth century, 4.30 letters.

I can think of two downsides of abjad languages, as I have written in my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024).

One is that in modern times, the major abjad languages - at least Arabic, Hebrew and Persian - are written from right to left. To the best of my knowledge, that was so in medieval times. The text of the Voynich manuscript, when it occurs in horizontal lines, is left-justified, and gives the overwhelming impression of having been written from left to right. That does not exclude precursor documents written from right to left; but the transposition would have vastly increased the workload for the scribes, and therefore the cost to the producer.

The other danger with the hypothesis of an abjad language is that any short string of letters has a sporting chance of making a word. In 2016, Bradley Hauer and Grzegorz Kondrak proposed Hebrew as the precursor language, and suggested a Hebrew translation of the first line of page f1r. I tested their mapping against longer chunks of Voynich text, and it did not produce sensible narrative.

Having spent some years in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, I am familiar with the Arabic alphabet. I have tested various correspondences between Voynich glyph frequencies and Arabic letter frequencies, and they yielded some short Arabic words, but they did not work for strings longer than three glyphs.

Likewise with Persian: the mappings produced some Persian words from strings up to three glyphs, but broke down at the four-glyph level.

In another post on this platform, I have proposed that in any proposed mapping from Voynich glyphs to a natural language, one needs to work with a sufficiently large chunk of Voynich text (at least a paragraph, or a page, or longer). In the case of abjad languages, I think it would be doubly important to work with reasonably long extracts from the Voynich text, in order to avoid producing apparently meaningful words by chance.

November 29, 2023

Voynich Reconsidered: mapping glyphs to letters

In previous articles om this platform, I reported on my experiments with the application of the Sukhotin algorithm to the Voynich manuscript. Boris V Sukhotin conceived the algorithm as a means of identifying the vowels in an unknown text, presuming only that the text was phonetic.

In these tests, I used Dr Mans Hulden's Python code for implementation of the algorithm.

The transliteration of the Voynich manuscript was one of my own devising, which I designated v211. It is one of the latest in a series, each of which is based on Glen Claston's v101 transliteration. It differs from v101 in the following principal respects:

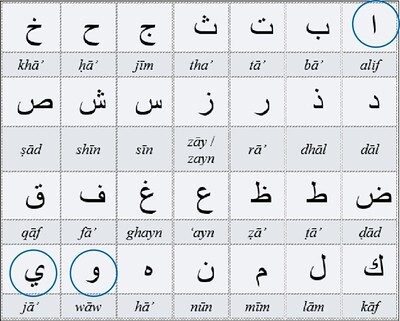

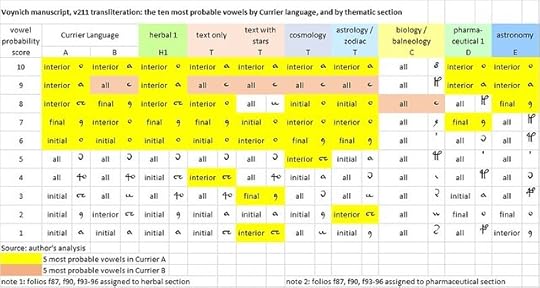

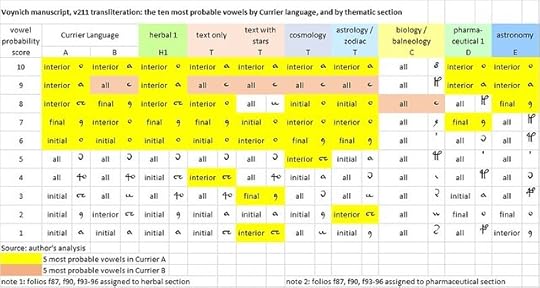

Applications of the Sukhotin algorithm for the identification of vowels, to my v211 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. Source: author's analysis.

I provisionally designated the language of the herbal section as Language H (which is very similar to Currier’s Language A); and that of the text, cosmology and zodiac sections as Language T (which has several probable vowels in common with Currier’s Language B). The biology, pharmaceutical and astronomy sections seem to be in different languages from either A or B.

Vocabularies

Different languages have different vocabularies. But European languages, even if not closely related, have some words in common. Below is a compilation of the ten most frequent words in selected medieval European languages. We see that there are five common Latin words - de, et, in, non and per - which reappear as common words in other European languages, although pronounced differently.

The ten most frequent words in medieval Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, German, Italian and Latin. Source: author's analysis.

If the Voynich manuscript has European precursor languages, and if we have evidence of different precursors for Currier A and B, and for the thematic sections, then we should expect to see some differences and some commonalities in the vocabulary between A and B, and from one section to another.

Accordingly, we assembled data on the counts of the 20 most frequent "words" in Currier Language A and B, and in each of the thematic sections.

In terms of commonality of vocabulary, Language H seems to be very close to Currier Language A. Language T (except for the "zodiac" section) is similar to Currier Language B. Languages D and E look like hybrids of A and B; C looks like a different language altogether.

The ten most frequent “words” in Currier’s Languages A and B: and in each of the thematic sections. Source: author's analysis.

Correlations and mappings

My idea of the next step is to correlate the frequencies of the glyphs in Languages H and T with the frequencies of the letters in some presumed precursor languages (for example, medieval Italian and medieval Latin). Then it should be possible to match vowel-glyphs with vowels, and consonant-glyphs with consonants, and thereby transliterate selected pages of the Voynich manuscript into the precursor languages.

If this process yields some recognisable words in, say, Latin or Italian, we might be on the right track. If not, there are several permutations of the approach, for example:

In these tests, I used Dr Mans Hulden's Python code for implementation of the algorithm.

The transliteration of the Voynich manuscript was one of my own devising, which I designated v211. It is one of the latest in a series, each of which is based on Glen Claston's v101 transliteration. It differs from v101 in the following principal respects:

* I used exclusively lower-case letters and Unicode characters.As illustrated below, these experiments seemed to identify a consistent set of vowels for the herbal section, and another broadly consistent set of vowels for the text-only, text-with-stars, cosmology and zodiac sections.

* I introduced the concept of position-dependency: specifically, for glyphs 1, 9, a and o, I used different Unicode characters depending on whether the glyph was in the initial, interior, final or isolated position.

* I combined groups of glyphs which are visually similar, for example the v101 glyphs 6, 7, 8 and &.

* I assumed that the v101 glyph 2, and its variants, were equivalent to the v101 glyph 1 with various accents (which may have several meanings, but which I have provisionally lumped together).

* I disaggregated several v101 glyphs which seemed to me to be strings of glyphs, notably m, M and n which seemed to contain embedded instances of the glyphs i or I.

Applications of the Sukhotin algorithm for the identification of vowels, to my v211 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. Source: author's analysis.

I provisionally designated the language of the herbal section as Language H (which is very similar to Currier’s Language A); and that of the text, cosmology and zodiac sections as Language T (which has several probable vowels in common with Currier’s Language B). The biology, pharmaceutical and astronomy sections seem to be in different languages from either A or B.

Vocabularies

Different languages have different vocabularies. But European languages, even if not closely related, have some words in common. Below is a compilation of the ten most frequent words in selected medieval European languages. We see that there are five common Latin words - de, et, in, non and per - which reappear as common words in other European languages, although pronounced differently.

The ten most frequent words in medieval Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, German, Italian and Latin. Source: author's analysis.

If the Voynich manuscript has European precursor languages, and if we have evidence of different precursors for Currier A and B, and for the thematic sections, then we should expect to see some differences and some commonalities in the vocabulary between A and B, and from one section to another.

Accordingly, we assembled data on the counts of the 20 most frequent "words" in Currier Language A and B, and in each of the thematic sections.

In terms of commonality of vocabulary, Language H seems to be very close to Currier Language A. Language T (except for the "zodiac" section) is similar to Currier Language B. Languages D and E look like hybrids of A and B; C looks like a different language altogether.

The ten most frequent “words” in Currier’s Languages A and B: and in each of the thematic sections. Source: author's analysis.

Correlations and mappings

My idea of the next step is to correlate the frequencies of the glyphs in Languages H and T with the frequencies of the letters in some presumed precursor languages (for example, medieval Italian and medieval Latin). Then it should be possible to match vowel-glyphs with vowels, and consonant-glyphs with consonants, and thereby transliterate selected pages of the Voynich manuscript into the precursor languages.

If this process yields some recognisable words in, say, Latin or Italian, we might be on the right track. If not, there are several permutations of the approach, for example:

• To use a different transliteration: that is, to redefine the glyphs. For example, in v211 I assumed that initial o, interior o and final o were different glyphs (or, more precisely, represented different precursor letters). We can recombine them.One further permutation which I am exploring is to consider that the precursor documents were in abbreviated languages. Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon Abbreviaturarum encourages us to conjecture that the Voynich initial 9 and final 9 are abbreviation symbols (and with different functions). To this end, I developed an abbreviated version of Dante’s Monarchia (1313-14), with the following substitutions:

• To swap some pairs of glyphs which have similar frequencies. For example in the herbal section, interior o is the most common glyph, accounting for 8.9 percent of all the glyphs, followed by final 9 with 8.6 percent of the glyphs. That might encourage us to map interior o to the most common letter in the precursor language (E in Italian, I in Latin). But within a given language, the letter frequencies differ from one document to another. Dante’s La Divina Commedia does not have exactly the same letter frequencies as the OVI corpus. So we have to allow ourselves flexibility in the glyph-to-letter mapping.

• To try other precursor languages. (So far, I have looked at Albanian, Bohemian, English, Finnish, French, Galician, German, Hungarian, Icelandic, Portuguese, Slovenian, Spanish, Turkish, Welsh and other languages, and in each case calculated the letter frequency distributions in selected medieval documents.)

• initial 9 (₉) for the prefixes co-, com-, con-, cum-, cun-This transforms, for example, the following line of Monarchia:

• final 9 (⁹) for the Latin suffixes -is, -os, -us, -um, -em, -am.

• from: “non tam de propria virtute confidens, quam de lumine largitoris”I have calculated the symbol frequencies in the abbreviated Monarchia and will see how they match up with the Voynich glyphs. More later.

• to: “non t⁹ de propria virtute ₉fidens qu⁹ de lumine largitor⁹”

October 23, 2023

Voynich Reconsidered: the Sukhotin algorithm

To my mind, the greatest mystery of the Voynich manuscript is the possibility that its inscrutable glyphs are a representation of a meaningful text in a natural human language or several such languages. As a corollary, I see the greatest challenge as the identification of that language or those languages.

In my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I set out my approach to a possible identification of precursor languages. In particular, in several chapters, I examined the application of frequency analysis.

I use the term "frequency analysis" to refer to the well-documented phenomenon that in most phonetic languages, the frequencies of the letters have a signature distribution. If a text is sufficiently long, even if we do not know the script, we can identify the most frequent symbols; indeed, we can rank every symbol, from most frequent to least frequent. In modern Italian, for example, the most frequent letters are E, A, I, O, N and T; in medieval Italian, as per the OVI corpus, the most frequent letters are E, A, I, O, N and R.

In the case of the Voynich manuscript, not only do we not know the script; but we do not know definitively where a glyph begins and ends. There are many visual forms in the manuscript which could be interpreted as one glyph or two, or even three. Furthermore, we do not know whether strings of glyphs, that look like words, really represent words in the presumed precursor languages. To address such uncertainties, we must be prepared to work with multiple transliterations of the manuscript: what I have called permutations of the text.

Likewise, we do not know the precursor languages. But we can work with multiple languages. We can assign a provisional ranking to languages, in terms of their probability. Here I have proposed that the medieval languages associated with a series of concentric circles, centered on Italy where Wilfrid Voynich rediscovered the manuscript, are more probable than others.

In Voynich Reconsidered,/i>, I wrote that frequency analysis, if applied systematically to a large number of permutations of text and languages, might be a basis for identifying meaning within the text. I added that this was a task for programmers with plenty of computing power: more than I possess.

Sukhotin

However, if we could classify the glyphs into those that represent vowels, and those that represent consonants, our task would be simpler by an order of magnitude. The number of permutations, at least, would be greatly reduced. In that case, we would only need to map vowel-glyphs to vowels, and consonant-glyphs to consonants. Most medieval European languages have about five vowels, and about twenty consonants (in both cases, for the moment, leaving aside accents and diacritics). In the Voynich manuscript, there are at most twenty-five distinct glyphs that account for over 95 percent of the text.

The question is therefore: if we have before us an unknown script, and we make the heroic assumption that the individual glyphs have been mapped from letters in a natural language, is there an algorithm for identifying the vowels and the consonants?

Thanks to the work of the French linguist Jacques Guy, I learned that such an algorithm existed. It was published in 1962 by Boris V. Sukhotin in his article “Экспериментальное видение буквенных классов с помощью EBM” (“Experimental Vision of Letter Classes Using EVM”), in Проблемы Структурной Лингвистики (Problems of structural linguistics).

Jacques Guy, writing in Cryptologia of July 1991, described Sukhotin’s algorithm as follows:

An extract from a cartoon in Jacques Guy's article "Vowel identification: an old (but good) algorithm" in Cryptologia of July 1991. The caption reads: “The artisan hit his thumb”. Image credit: JD.

Goldsmith and Xanthos, in their article "Learning Phonological Categories" (Language, March 2009), observed that Sukhotin had made another basic assumption. They wrote:

I infer that the way the Sukhotin algorithm works is as follows:

Sukhotin was evidently working in the tradition of the Russian mathematician Andrey Andreyevich Markov, who created the concept now known as Markov chains, or Markov processes. One of Markov’s earliest works was a study, in 1913, of the frequencies of vowels and consonants in Pushkin’s novel Eugene Onegin. This pathbreaking analysis was, in part, the inspiration for the chapter in Voynich Reconsidered on mathematical approaches to the Voynich manuscript, which I titled, simply, "Markov".

In my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I set out my approach to a possible identification of precursor languages. In particular, in several chapters, I examined the application of frequency analysis.

I use the term "frequency analysis" to refer to the well-documented phenomenon that in most phonetic languages, the frequencies of the letters have a signature distribution. If a text is sufficiently long, even if we do not know the script, we can identify the most frequent symbols; indeed, we can rank every symbol, from most frequent to least frequent. In modern Italian, for example, the most frequent letters are E, A, I, O, N and T; in medieval Italian, as per the OVI corpus, the most frequent letters are E, A, I, O, N and R.

In the case of the Voynich manuscript, not only do we not know the script; but we do not know definitively where a glyph begins and ends. There are many visual forms in the manuscript which could be interpreted as one glyph or two, or even three. Furthermore, we do not know whether strings of glyphs, that look like words, really represent words in the presumed precursor languages. To address such uncertainties, we must be prepared to work with multiple transliterations of the manuscript: what I have called permutations of the text.

Likewise, we do not know the precursor languages. But we can work with multiple languages. We can assign a provisional ranking to languages, in terms of their probability. Here I have proposed that the medieval languages associated with a series of concentric circles, centered on Italy where Wilfrid Voynich rediscovered the manuscript, are more probable than others.

In Voynich Reconsidered,/i>, I wrote that frequency analysis, if applied systematically to a large number of permutations of text and languages, might be a basis for identifying meaning within the text. I added that this was a task for programmers with plenty of computing power: more than I possess.

Sukhotin

However, if we could classify the glyphs into those that represent vowels, and those that represent consonants, our task would be simpler by an order of magnitude. The number of permutations, at least, would be greatly reduced. In that case, we would only need to map vowel-glyphs to vowels, and consonant-glyphs to consonants. Most medieval European languages have about five vowels, and about twenty consonants (in both cases, for the moment, leaving aside accents and diacritics). In the Voynich manuscript, there are at most twenty-five distinct glyphs that account for over 95 percent of the text.

The question is therefore: if we have before us an unknown script, and we make the heroic assumption that the individual glyphs have been mapped from letters in a natural language, is there an algorithm for identifying the vowels and the consonants?

Thanks to the work of the French linguist Jacques Guy, I learned that such an algorithm existed. It was published in 1962 by Boris V. Sukhotin in his article “Экспериментальное видение буквенных классов с помощью EBM” (“Experimental Vision of Letter Classes Using EVM”), in Проблемы Структурной Лингвистики (Problems of structural linguistics).

Jacques Guy, writing in Cryptologia of July 1991, described Sukhotin’s algorithm as follows:

“Sukhotin … assume[s] a state of complete ignorance about the language, except that the writing system is alphabetical. … Sukhotin had observed that vowels tend to occur next to consonants rather than next to vowels.”Guy then worked through a manual example of Sukhotin’s algorithm, applied to the word SAGITTA, and found that the algorithm correctly identified the vowels as A and I, and the consonants as G, S and T.

An extract from a cartoon in Jacques Guy's article "Vowel identification: an old (but good) algorithm" in Cryptologia of July 1991. The caption reads: “The artisan hit his thumb”. Image credit: JD.

Goldsmith and Xanthos, in their article "Learning Phonological Categories" (Language, March 2009), observed that Sukhotin had made another basic assumption. They wrote:

"Sukhotin's algorithm ... relies on two fundamental assumptions: first, that the most frequent symbol in a transcription is always a vowel, and second, that vowels and consonants tend to alternate more often than not."Member MarcoP of the Voynich Ninja forum has alerted me that Goldsmith's and Xanthos's interpretation is not quite correct. Sukhotin assumed that the most probable vowel was the symbol that most often occurred adjacent to another symbol. A symbol which is interior to a word has two neighbors; an initial or final symbol has only one; an isolated symbol has none.

I infer that the way the Sukhotin algorithm works is as follows:

• Find the symbol with the most occurrences adjacent to another; this is most probably a vowel.This is of course a statistical approach, based on probabilities. It does not exclude pairs of vowels. Most phonetic languages have a few relatively common vowel pairs. For example, as we see from Stefan Trost's excellent website, in modern Italian the most frequent vowel pair is "IO", with a frequency of 1.1 percent; in classical Latin, "AE" (1.0 percent); in modern French, "AI" (1.9 percent).

• The immediately preceding and following symbols (if any) are probably consonants.

• If those symbols occur elsewhere in the text, the immediately preceding and following symbols (if any) are probably vowels.

• And so on, iteratively, until each symbol has been identified as either a probable vowel or a probable consonant.

Sukhotin was evidently working in the tradition of the Russian mathematician Andrey Andreyevich Markov, who created the concept now known as Markov chains, or Markov processes. One of Markov’s earliest works was a study, in 1913, of the frequencies of vowels and consonants in Pushkin’s novel Eugene Onegin. This pathbreaking analysis was, in part, the inspiration for the chapter in Voynich Reconsidered on mathematical approaches to the Voynich manuscript, which I titled, simply, "Markov".

Published on October 23, 2023 14:35

•

Tags:

boris-sukhotin, goldsmith-xanthos, jacques-guy, massimiliano-zattera, stefan-trost, voynich

September 22, 2023

Voynich Reconsidered: a research philosophy

Voynich Reconsidered is my second book in the series that I like to call “Great 20th Century Mysteries”. The publisher is Schiffer Books of Atglen, Pennsylvania.

I have taken this opportunity to set out some of the ideas that underlay my philosophy in writing this book.

Image credit: Schiffer Books.

It is universally acknowledged that the Voynich manuscript is a mystery. I believe it was Brigadier John H. Tiltman, writing in 1967 for the US National Security Agency, who first gave it the sobriquet “the most mysterious manuscript in the world". For some researchers, the mystery lies chiefly in the bizarre drawings of plants, cosmic objects, signs of the zodiac, steampunk receptacles, and little naked ladies in pools of blue or green water. For others (and for myself), the mystery resides in the hundreds of thousands of elegant glyphs, arranged in strings that have the appearance of words.

By some interpretations, there are over two hundred distinct glyphs, though only about twenty are used extensively. A handful of these glyphs resemble letters in Latin script, or Arabic numerals; one or two resemble the ornamental flourishes in a monastic letter dated 1172 from San Savino, Italy; the majority resemble nothing on this earth, and have never been seen anywhere else.

In calling the manuscript a twentieth century mystery, I was inclined to date the birth of the mystery either to 1912 when, according to Wilfrid Voynich, he rediscovered the manuscript which later bore his name; or to 1921 when Voynich made his first presentation on the manuscript, to an audience in Philadelphia.

The calfskin vellum, on which the drawings and glyphs were inscribed, has been sampled for radiocarbon analysis. The five samples yielded dates predominantly between the mid-fourteenth and the mid-fifteenth century. The inks are inorganic, and no extant technology permits us to date them.

We are therefore to conjecture any date we like (after about 1450, and no later than 1921) for the creation of the manuscript. However, to my mind the probabilities favor the fifteenth century. I think that, the more time we allow between the vellum and the writing, the less the chances for the creators to find a stock of unused material.

In approaching the mystery, I made a decision to focus on what, for want of a better word, I called the text. I use the term “text” to refer to the strings of glyphs that look like words. The strings are, for the most part, arranged in horizontal lines, that appear to have been written from left to right. The lines are often arranged in groups that we might call paragraphs. There is nothing resembling punctuation, and therefore there is no sequence of glyph strings that we could call a sentence. There is no indication that the text wraps from one line to the next, nor from one page to the next.

The search for meaning

The central element of the mystery appeared to me to be whether or not the text contained meaning.

In my research for Voynich Reconsidered, I became aware of an argument that the text had no meaning. On this view, the scribes of the Voynich manuscript generated the text by means of an algorithm. Some authors have proposed that a suitable algorithm can produce text which emulates some of the statistical properties of the Voynich manuscript.

I believe that the hypothesis of the absence of meaning is not amenable to proof. In any case, to my mind it was more interesting to assume that the text contained some meaning, and to see where that assumption might lead.

As my work progressed, I began to imagine the workplace where the manuscript was created. There must have been a producer: a person who conceptualised the project and paid for it. There was a team of scribes: at least two and possibly up to eight, according to the pathbreaking researcher Prescott Currier. One can easily imagine assistants: furnishing, cleaning, catering, refreshing the artistic supplies. The work must have taken at least several months, maybe years. No matter in what century this took place, the producer must have been wealthy, to afford the materials and manpower for such a project.

We can imagine the producer also as director. He or she had a vision for what was to be produced: a manuscript of over two hundred pages, bursting with illustrations in color, and crammed with text in a script sui generis. He or she had to convey that vision to the scribes, and to set down the instructions whereby they would execute it. It seemed to me, mindful of Occam’s Razor, that those instructions should be sufficiently simple that the scribes could follow them without continual recourse to the director. Likewise, it seemed probable that a single set of instructions prevailed over a period of months or years.

This brought me to the idea of an author: more specifically, a source document or documents.

Precursors

It seemed to be a logical and simple assumption that the text of the Voynich manuscript had a precursor. This document (or set of documents) contained all the meaningful text that would be entered in the Voynich manuscript. If these documents were meaningful, they had to be written in natural human languages: ones that were spoken and written, or at least understood, in the place where the manuscript was created.

These considerations led me to think about where that place might be.

In 1921, Voynich told his American audience that he had found the manuscript in southern Europe. After his death, his widow Ethel Lilian Voynich disclosed that the place, more precisely, had been Frascati in Italy. The languages spoken in Italy in the fifteenth century were Latin and a variety of vernacular languages, among which Tuscan would become the foundation of modern Italian. I recalled that Dante Alighieri had written La Divina Commedia in Tuscan, in 1308-1321, and Monarchia in Latin around 1312-1313. If the manuscript had been produced in Italy, Occam’s Razor would direct us towards Latin and Tuscan-Italian as the most probable precursor languages.

Nevertheless, it would be prudent to allow for the manuscript to have travelled to the place where Voynich found it. Here, I was mindful of the distance-decay hypothesis: the well-documented concept that, the greater the distance between two places, the less the probability of any human or material transaction between those places. I was therefore disposed to think of concentric rings, centered on Italy, and to place the origin of the manuscript, and its precursor languages, within those rings.

If this idea had merit, I could conjecture that the next most probable precursor languages would be French, German and Albanian (as spoken and written at the presumed time of creation of the manuscript). After that, one might reasonably look at the Slavic and Iberian languages, English and Greek. Farther afield, I felt that the probabilities were not such as to justify the research effort.

In short, I could identify at least ten or a dozen European languages which seemed worthy of the effort of correlation with the Voynich manuscript.

Occam

As to the analytical approach: I felt that the Voynich producer would have wished to simplify the task of the scribes. I could imagine a scenario in which the producer handed the scribes a set of documents, written in European languages, in (most probably) the Latin script, or (less probably) another script such as Cyrillic, Greek or Glagolitic. The producer then instructed the scribes to transcribe these documents into the Voynich glyphs. To my mind, the simplest possible instruction would be a one-to-one mapping: one Latin (or other) letter corresponding uniquely to a Voynich glyph.

I was aware of arguments that any such mapping would not necessarily be one-to-one; that some form of encipherment had taken place, before or after the mapping; or that some unknown part of the Voynich text was meaningless filler or junk. All of this is possible. Indeed, in Voynich Reconsidered I have addressed some alternatives: for example, mappings based on bigrams or trigrams, or mappings between glyph strings and precursor words. I considered the possibility that a glyph in the initial position might map differently from the same glyph in the final or an intermediate position. But as a research philosophy, I felt that the permutations of a one-to-one mapping should be thoroughly explored before a major effort was devoted to other hypotheses.

If our working assumption (and it is no more than that) is that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping, then we have a useful tool in the form of frequency analysis. Edgar Allen Poe made frequency analysis the centerpiece of his story of "The Gold Bug"; so did Sherlock Holmes in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men". A one-to-one mapping of letters to other letters, or to any other group of symbols, preserves the frequencies of the original letters. In all or most natural languages, the letters have a signature frequency distribution: in modern English, the most common letters are E, T, A, O, I and N.

Readers may object that many researchers have tried frequency analysis on the Voynich manuscript. Indeed, they have; but I believe that the permutations have never been fully explored. In using the term “permutations”, I have in mind a matrix with at least two axes. One axis is the precursor language. We may have to test at least ten or twelve such languages. Another axis is the text itself.

Here, we need to elaborate what we mean by the text.

The Voynich manuscript resides at the Beinecke Library of Rare Books and Manuscripts, at Yale University. The Library has performed an immense service to researchers in scanning every page of the Voynich manuscript, in color and at high resolution, and in making those images freely available on the internet. The text is there for all to see.

What is a glyph?

Nevertheless, we still have to ask at least two questions: what is a glyph? and what is a glyph string?

In the era before cheap computing power, researchers were obliged to create transliterations of the Voynich text, according to their respective individual perceptions of where a glyph began and ended, and where a glyph string began and ended. The two most widely used transliterations are Jorge Stolfi’s EVA (now interpreted as Extended Voynich Alphabet) and Glen Claston’s v101. We might more properly refer to the transliterations as keyboard assignments, since the main objective was to map Voynich glyphs to symbols on an English keyboard. Inevitably, there were differences of interpretation.

Here is just one example. Among the Voynich glyphs, there is one which resembles the Arabic numeral 8. In EVA, this glyph is assigned the letter d (with no necessary intention that it would have been pronounced as d, or mapped from the Latin letter d). In v101, the same glyph receives four keyboard assignments: 8, 7, 6 and &, distinguished by minor variations in the quill strokes. In EVA, a glyph resembling a stylised letter m is assigned the keys iin; in v101, the glyph is simply m. Thereby, one of the famous and ubiquitous Voynich “words” in EVA is daiin, and in v101 is 8am, or 7am, or 6am, or &am.

Clearly, a glyph frequency distribution derived from EVA will not be applicable to v101, and vice versa.

When we turn to glyph strings, we encounter a problem which has been less explored but is nevertheless significant. We do not know where a glyph string begins and ends. For sure, in the manuscript there are spaces, of variable width, between glyph strings; and glyph strings seem to stop when they reach the right-hand margin of the page. It is tempting to assume that spaces and line breaks represent word breaks in the presumed precursor documents. But in our modern keyboards, we have a “space” key; when we press it, the computer enters a “space” character, which is usually invisible on the screen. By analogy, spaces and line breaks in the Voynich manuscript might represent letters in the precursor documents: in which case, all analysis of Voynich “words” will break down.

There is more. In the Voynich manuscript, there are thousands of glyph strings which seem to have two parts, each of which is a “word” occurring elsewhere in the manuscript. Are these strings compound “words”; or should we read each such string as two “words”, with the word break accidentally or intentionally omitted? We do not know.

To my mind, these entirely legitimate differences of interpretation required a perception of the Voynich text, not as a single document but as multiple documents, each one based on a permutation of the assumptions that we made about where glyphs and glyph strings began and ended.

I suspect that the late Glen Claston had something like this in mind when he created v101. I conjecture that he intended to allow his readers, if they so wished, to combine some of his multiple keyboard assignments, for example 8, 7, 6 and &; or even to disaggregate some of his assignments, so that his [m] could become [in] or [iiN]. In such situations, the readers would generate successor transliterations which could be numbered v102, v103 and so on. I did precisely this in one of the chapters of Voynich Reconsidered, with alternative transliterations which I numbered up to v104. In subsequent unpublished research, I have experimented with transliterations numbered up to v112.

The matrix

With (say) twelve possible precursor languages, and (say) twelve possible transliterations, we have a matrix of 144 permutations of our assumptions. Each permutation will generate a mapping between letters in a precursor language and glyphs in the Voynich manuscript. For each permutation, we then have to select a suitable chunk of the Voynich manuscript, map it to the precursor language, and see whether the result makes any kind of sense. That final step requires a good knowledge of the precursor language (probably a medieval version of the language), or at least access to large corpora of text in that language.

There are more axes to the matrix. In any natural language, frequency analysis is quite accurate for the most common letters. But languages evolve over time, and even in the same era, the letter frequencies will not be identical from one document to another. We should not expect the letter frequencies in the Gettysburg Address to be identical to those in a modern State of the Union. Therefore, our testing needs to allow for permutations in the ranking of letters, at least for the less common ones.

Here, I think, is where research on the Voynich manuscript, over the last century and more, has run up against the limits of individual patience and persistence. Testing all the permutations is a large effort: too large for an individual (such as myself) with a laptop and little or no knowledge of programming. Fortunately, in modern times computing power is cheap, and programming skills are widespread.

In Voynich Reconsidered, I have attempted to set out a strategy whereby interested and motivated readers, or groups of readers, could approach the text of the Voynich manuscript. They would require a clear focus, no preconceived narratives, skills in some programming languages, and plenty of computing power. This strategy, I believe, will discover meaning somewhere in the Voynich manuscript, if meaning is there to be found.

I have taken this opportunity to set out some of the ideas that underlay my philosophy in writing this book.

Image credit: Schiffer Books.

It is universally acknowledged that the Voynich manuscript is a mystery. I believe it was Brigadier John H. Tiltman, writing in 1967 for the US National Security Agency, who first gave it the sobriquet “the most mysterious manuscript in the world". For some researchers, the mystery lies chiefly in the bizarre drawings of plants, cosmic objects, signs of the zodiac, steampunk receptacles, and little naked ladies in pools of blue or green water. For others (and for myself), the mystery resides in the hundreds of thousands of elegant glyphs, arranged in strings that have the appearance of words.

By some interpretations, there are over two hundred distinct glyphs, though only about twenty are used extensively. A handful of these glyphs resemble letters in Latin script, or Arabic numerals; one or two resemble the ornamental flourishes in a monastic letter dated 1172 from San Savino, Italy; the majority resemble nothing on this earth, and have never been seen anywhere else.

In calling the manuscript a twentieth century mystery, I was inclined to date the birth of the mystery either to 1912 when, according to Wilfrid Voynich, he rediscovered the manuscript which later bore his name; or to 1921 when Voynich made his first presentation on the manuscript, to an audience in Philadelphia.

The calfskin vellum, on which the drawings and glyphs were inscribed, has been sampled for radiocarbon analysis. The five samples yielded dates predominantly between the mid-fourteenth and the mid-fifteenth century. The inks are inorganic, and no extant technology permits us to date them.

We are therefore to conjecture any date we like (after about 1450, and no later than 1921) for the creation of the manuscript. However, to my mind the probabilities favor the fifteenth century. I think that, the more time we allow between the vellum and the writing, the less the chances for the creators to find a stock of unused material.

In approaching the mystery, I made a decision to focus on what, for want of a better word, I called the text. I use the term “text” to refer to the strings of glyphs that look like words. The strings are, for the most part, arranged in horizontal lines, that appear to have been written from left to right. The lines are often arranged in groups that we might call paragraphs. There is nothing resembling punctuation, and therefore there is no sequence of glyph strings that we could call a sentence. There is no indication that the text wraps from one line to the next, nor from one page to the next.

The search for meaning

The central element of the mystery appeared to me to be whether or not the text contained meaning.

In my research for Voynich Reconsidered, I became aware of an argument that the text had no meaning. On this view, the scribes of the Voynich manuscript generated the text by means of an algorithm. Some authors have proposed that a suitable algorithm can produce text which emulates some of the statistical properties of the Voynich manuscript.

I believe that the hypothesis of the absence of meaning is not amenable to proof. In any case, to my mind it was more interesting to assume that the text contained some meaning, and to see where that assumption might lead.

As my work progressed, I began to imagine the workplace where the manuscript was created. There must have been a producer: a person who conceptualised the project and paid for it. There was a team of scribes: at least two and possibly up to eight, according to the pathbreaking researcher Prescott Currier. One can easily imagine assistants: furnishing, cleaning, catering, refreshing the artistic supplies. The work must have taken at least several months, maybe years. No matter in what century this took place, the producer must have been wealthy, to afford the materials and manpower for such a project.

We can imagine the producer also as director. He or she had a vision for what was to be produced: a manuscript of over two hundred pages, bursting with illustrations in color, and crammed with text in a script sui generis. He or she had to convey that vision to the scribes, and to set down the instructions whereby they would execute it. It seemed to me, mindful of Occam’s Razor, that those instructions should be sufficiently simple that the scribes could follow them without continual recourse to the director. Likewise, it seemed probable that a single set of instructions prevailed over a period of months or years.

This brought me to the idea of an author: more specifically, a source document or documents.

Precursors

It seemed to be a logical and simple assumption that the text of the Voynich manuscript had a precursor. This document (or set of documents) contained all the meaningful text that would be entered in the Voynich manuscript. If these documents were meaningful, they had to be written in natural human languages: ones that were spoken and written, or at least understood, in the place where the manuscript was created.

These considerations led me to think about where that place might be.

In 1921, Voynich told his American audience that he had found the manuscript in southern Europe. After his death, his widow Ethel Lilian Voynich disclosed that the place, more precisely, had been Frascati in Italy. The languages spoken in Italy in the fifteenth century were Latin and a variety of vernacular languages, among which Tuscan would become the foundation of modern Italian. I recalled that Dante Alighieri had written La Divina Commedia in Tuscan, in 1308-1321, and Monarchia in Latin around 1312-1313. If the manuscript had been produced in Italy, Occam’s Razor would direct us towards Latin and Tuscan-Italian as the most probable precursor languages.

Nevertheless, it would be prudent to allow for the manuscript to have travelled to the place where Voynich found it. Here, I was mindful of the distance-decay hypothesis: the well-documented concept that, the greater the distance between two places, the less the probability of any human or material transaction between those places. I was therefore disposed to think of concentric rings, centered on Italy, and to place the origin of the manuscript, and its precursor languages, within those rings.

If this idea had merit, I could conjecture that the next most probable precursor languages would be French, German and Albanian (as spoken and written at the presumed time of creation of the manuscript). After that, one might reasonably look at the Slavic and Iberian languages, English and Greek. Farther afield, I felt that the probabilities were not such as to justify the research effort.

In short, I could identify at least ten or a dozen European languages which seemed worthy of the effort of correlation with the Voynich manuscript.

Occam

As to the analytical approach: I felt that the Voynich producer would have wished to simplify the task of the scribes. I could imagine a scenario in which the producer handed the scribes a set of documents, written in European languages, in (most probably) the Latin script, or (less probably) another script such as Cyrillic, Greek or Glagolitic. The producer then instructed the scribes to transcribe these documents into the Voynich glyphs. To my mind, the simplest possible instruction would be a one-to-one mapping: one Latin (or other) letter corresponding uniquely to a Voynich glyph.

I was aware of arguments that any such mapping would not necessarily be one-to-one; that some form of encipherment had taken place, before or after the mapping; or that some unknown part of the Voynich text was meaningless filler or junk. All of this is possible. Indeed, in Voynich Reconsidered I have addressed some alternatives: for example, mappings based on bigrams or trigrams, or mappings between glyph strings and precursor words. I considered the possibility that a glyph in the initial position might map differently from the same glyph in the final or an intermediate position. But as a research philosophy, I felt that the permutations of a one-to-one mapping should be thoroughly explored before a major effort was devoted to other hypotheses.

If our working assumption (and it is no more than that) is that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping, then we have a useful tool in the form of frequency analysis. Edgar Allen Poe made frequency analysis the centerpiece of his story of "The Gold Bug"; so did Sherlock Holmes in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men". A one-to-one mapping of letters to other letters, or to any other group of symbols, preserves the frequencies of the original letters. In all or most natural languages, the letters have a signature frequency distribution: in modern English, the most common letters are E, T, A, O, I and N.

Readers may object that many researchers have tried frequency analysis on the Voynich manuscript. Indeed, they have; but I believe that the permutations have never been fully explored. In using the term “permutations”, I have in mind a matrix with at least two axes. One axis is the precursor language. We may have to test at least ten or twelve such languages. Another axis is the text itself.

Here, we need to elaborate what we mean by the text.

The Voynich manuscript resides at the Beinecke Library of Rare Books and Manuscripts, at Yale University. The Library has performed an immense service to researchers in scanning every page of the Voynich manuscript, in color and at high resolution, and in making those images freely available on the internet. The text is there for all to see.

What is a glyph?

Nevertheless, we still have to ask at least two questions: what is a glyph? and what is a glyph string?

In the era before cheap computing power, researchers were obliged to create transliterations of the Voynich text, according to their respective individual perceptions of where a glyph began and ended, and where a glyph string began and ended. The two most widely used transliterations are Jorge Stolfi’s EVA (now interpreted as Extended Voynich Alphabet) and Glen Claston’s v101. We might more properly refer to the transliterations as keyboard assignments, since the main objective was to map Voynich glyphs to symbols on an English keyboard. Inevitably, there were differences of interpretation.

Here is just one example. Among the Voynich glyphs, there is one which resembles the Arabic numeral 8. In EVA, this glyph is assigned the letter d (with no necessary intention that it would have been pronounced as d, or mapped from the Latin letter d). In v101, the same glyph receives four keyboard assignments: 8, 7, 6 and &, distinguished by minor variations in the quill strokes. In EVA, a glyph resembling a stylised letter m is assigned the keys iin; in v101, the glyph is simply m. Thereby, one of the famous and ubiquitous Voynich “words” in EVA is daiin, and in v101 is 8am, or 7am, or 6am, or &am.

Clearly, a glyph frequency distribution derived from EVA will not be applicable to v101, and vice versa.

When we turn to glyph strings, we encounter a problem which has been less explored but is nevertheless significant. We do not know where a glyph string begins and ends. For sure, in the manuscript there are spaces, of variable width, between glyph strings; and glyph strings seem to stop when they reach the right-hand margin of the page. It is tempting to assume that spaces and line breaks represent word breaks in the presumed precursor documents. But in our modern keyboards, we have a “space” key; when we press it, the computer enters a “space” character, which is usually invisible on the screen. By analogy, spaces and line breaks in the Voynich manuscript might represent letters in the precursor documents: in which case, all analysis of Voynich “words” will break down.

There is more. In the Voynich manuscript, there are thousands of glyph strings which seem to have two parts, each of which is a “word” occurring elsewhere in the manuscript. Are these strings compound “words”; or should we read each such string as two “words”, with the word break accidentally or intentionally omitted? We do not know.

To my mind, these entirely legitimate differences of interpretation required a perception of the Voynich text, not as a single document but as multiple documents, each one based on a permutation of the assumptions that we made about where glyphs and glyph strings began and ended.

I suspect that the late Glen Claston had something like this in mind when he created v101. I conjecture that he intended to allow his readers, if they so wished, to combine some of his multiple keyboard assignments, for example 8, 7, 6 and &; or even to disaggregate some of his assignments, so that his [m] could become [in] or [iiN]. In such situations, the readers would generate successor transliterations which could be numbered v102, v103 and so on. I did precisely this in one of the chapters of Voynich Reconsidered, with alternative transliterations which I numbered up to v104. In subsequent unpublished research, I have experimented with transliterations numbered up to v112.

The matrix

With (say) twelve possible precursor languages, and (say) twelve possible transliterations, we have a matrix of 144 permutations of our assumptions. Each permutation will generate a mapping between letters in a precursor language and glyphs in the Voynich manuscript. For each permutation, we then have to select a suitable chunk of the Voynich manuscript, map it to the precursor language, and see whether the result makes any kind of sense. That final step requires a good knowledge of the precursor language (probably a medieval version of the language), or at least access to large corpora of text in that language.

There are more axes to the matrix. In any natural language, frequency analysis is quite accurate for the most common letters. But languages evolve over time, and even in the same era, the letter frequencies will not be identical from one document to another. We should not expect the letter frequencies in the Gettysburg Address to be identical to those in a modern State of the Union. Therefore, our testing needs to allow for permutations in the ranking of letters, at least for the less common ones.

Here, I think, is where research on the Voynich manuscript, over the last century and more, has run up against the limits of individual patience and persistence. Testing all the permutations is a large effort: too large for an individual (such as myself) with a laptop and little or no knowledge of programming. Fortunately, in modern times computing power is cheap, and programming skills are widespread.

In Voynich Reconsidered, I have attempted to set out a strategy whereby interested and motivated readers, or groups of readers, could approach the text of the Voynich manuscript. They would require a clear focus, no preconceived narratives, skills in some programming languages, and plenty of computing power. This strategy, I believe, will discover meaning somewhere in the Voynich manuscript, if meaning is there to be found.

January 29, 2023

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: Noiser

The podcast "A Short History of D. B. Cooper", written by Joe Viner, with Bob Edwards and Darren Schaefer, is out on the award-winning Noiser channel:

https://podfollow.com/short-history-o...

Image credit: Noiser.

https://podfollow.com/short-history-o...

Image credit: Noiser.

Published on January 29, 2023 23:54

•

Tags:

dbcooper

December 19, 2022

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: "Crime and Entertainment"

My podcast with Wade "Hollywood Wade" Williamson at Crime and Entertainment is now live on apple and other platforms:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast...

and is also on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0x5aL...

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast...

and is also on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0x5aL...

Published on December 19, 2022 08:08

•

Tags:

dbcooper

August 11, 2022

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: an FBI perspective

On August 10, 2022 I was fortunate to have a telephone conversation with a former senior FBI agent who was familiar with the case of Flight 305, and who kindly responded to a long list of technical questions that I had prepared. Among his perspectives were the following:

The Portland to Seattle segment:

* The FBI interviewed every passenger (of course, other than the hijacker).

* The FBI has no testimony (other than that of the Northwest Airlines ticket agent) that characterized the hijacker as having the appearance of a blue-collar worker.

* The junior stewardess made several statements to the FBI, and generally characterized the hijacker as an executive type.

* The FBI generally did not view the hijacker as an executive type, but more as a "middle-class worker".

The Seattle to Reno segment:

* The FBI has no technical data on the segment, other than the "Air Force map", which the FBI received from the US Air Force with no accompanying data or methodology;

* The FBI has no audio recordings of any kind, and no transcripts of radio communications other than what has been published.

* The FBI has no technical or communications data from the chase planes.

* The FBI has no reason to question the statements of Northwest's Director of Flight Operations (Technical) that Flight 305 was on autopilot throughout most of this segment.

The sled test flight:

* The FBI did not receive a technical report on this flight, and has no technical data, audio recordings or communications transcripts from the flight.

* The 8mm film from the chase plane still exists.

The tests at Takhli, Thailand:

* The FBI did not and could not interview the employees of Southern Air Transport or Air America who were involved in these tests.

Military records:

* The FBI did obtain the service histories of suspects with military records, some of which are still classified.

The Portland to Seattle segment:

* The FBI interviewed every passenger (of course, other than the hijacker).

* The FBI has no testimony (other than that of the Northwest Airlines ticket agent) that characterized the hijacker as having the appearance of a blue-collar worker.

* The junior stewardess made several statements to the FBI, and generally characterized the hijacker as an executive type.

* The FBI generally did not view the hijacker as an executive type, but more as a "middle-class worker".

The Seattle to Reno segment:

* The FBI has no technical data on the segment, other than the "Air Force map", which the FBI received from the US Air Force with no accompanying data or methodology;

* The FBI has no audio recordings of any kind, and no transcripts of radio communications other than what has been published.

* The FBI has no technical or communications data from the chase planes.

* The FBI has no reason to question the statements of Northwest's Director of Flight Operations (Technical) that Flight 305 was on autopilot throughout most of this segment.

The sled test flight:

* The FBI did not receive a technical report on this flight, and has no technical data, audio recordings or communications transcripts from the flight.

* The 8mm film from the chase plane still exists.

The tests at Takhli, Thailand:

* The FBI did not and could not interview the employees of Southern Air Transport or Air America who were involved in these tests.

Military records:

* The FBI did obtain the service histories of suspects with military records, some of which are still classified.

July 11, 2022

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: review

Aeroplane Magazine reviewed "D. B. Cooper and Flight 305":

"Edwards’ new book re-examines the evidence ... he offers an extremely detailed investigation ... An impressive feat of research."

Published on July 11, 2022 11:54

•

Tags:

dbcooper

June 20, 2022

Voynich Reconsidered: a 20th century mystery

Voynich Reconsidered is my second book in the series that I like to call "Great 20th Century Mysteries".

The book is an investigation, primarily from my perspective as a mathematician, into the possible meaning of the Voynich Manuscript.

In the year 1637, a Bohemian scholar sent a mysterious book to the celebrated professor Athanasius Kircher in Rome. Perhaps it was what we now call the Voynich manuscript; we do not know for sure. Kircher promised to decipher it when the mood took him. But he never did.

That's where our story begins.

The book is an investigation, primarily from my perspective as a mathematician, into the possible meaning of the Voynich Manuscript.

In the year 1637, a Bohemian scholar sent a mysterious book to the celebrated professor Athanasius Kircher in Rome. Perhaps it was what we now call the Voynich manuscript; we do not know for sure. Kircher promised to decipher it when the mood took him. But he never did.

That's where our story begins.

June 2, 2022

D. B. Cooper and Flight 305: "Vanished"

Chris Williamson, host of the "Vanished" podcast, is planning to publish transcripts of the show in book form.

Look out for Mr Williamson's (as yet untitled) book on the hijacker of Flight 305. The book should include transcripts from the following podcasts:

Image credit: Chris Williamson / Vanished Show

Look out for Mr Williamson's (as yet untitled) book on the hijacker of Flight 305. The book should include transcripts from the following podcasts:

Season 2 Episode 11: Vanished: DB Cooper "November 24th, 1971" https://www.vanishedshow.com/podcast/...In the transcript of Episode 12, readers should find my conversation with Mr Williamson on "D. B. Cooper and Flight 305", broadcast on November 24, 2021.

Season 2 Episode 12: Vanished: DB Cooper "A Dark Horse" https://www.vanishedshow.com/podcast/...

Season 2 Episode 13: Vanished: DB Cooper "Trial by Jury" https://www.vanishedshow.com/podcast/...

Image credit: Chris Williamson / Vanished Show

Published on June 02, 2022 09:32

•

Tags:

dbcooper

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers