Voynich Reconsidered: mapping glyphs to letters

In previous articles om this platform, I reported on my experiments with the application of the Sukhotin algorithm to the Voynich manuscript. Boris V Sukhotin conceived the algorithm as a means of identifying the vowels in an unknown text, presuming only that the text was phonetic.

In these tests, I used Dr Mans Hulden's Python code for implementation of the algorithm.

The transliteration of the Voynich manuscript was one of my own devising, which I designated v211. It is one of the latest in a series, each of which is based on Glen Claston's v101 transliteration. It differs from v101 in the following principal respects:

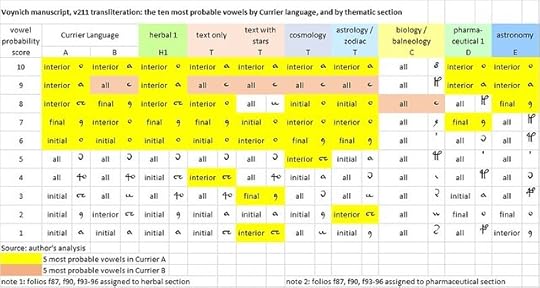

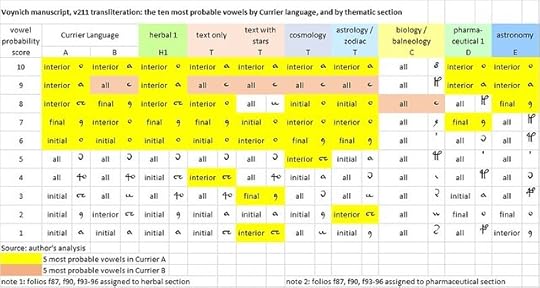

Applications of the Sukhotin algorithm for the identification of vowels, to my v211 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. Source: author's analysis.

I provisionally designated the language of the herbal section as Language H (which is very similar to Currier’s Language A); and that of the text, cosmology and zodiac sections as Language T (which has several probable vowels in common with Currier’s Language B). The biology, pharmaceutical and astronomy sections seem to be in different languages from either A or B.

Vocabularies

Different languages have different vocabularies. But European languages, even if not closely related, have some words in common. Below is a compilation of the ten most frequent words in selected medieval European languages. We see that there are five common Latin words - de, et, in, non and per - which reappear as common words in other European languages, although pronounced differently.

The ten most frequent words in medieval Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, German, Italian and Latin. Source: author's analysis.

If the Voynich manuscript has European precursor languages, and if we have evidence of different precursors for Currier A and B, and for the thematic sections, then we should expect to see some differences and some commonalities in the vocabulary between A and B, and from one section to another.

Accordingly, we assembled data on the counts of the 20 most frequent "words" in Currier Language A and B, and in each of the thematic sections.

In terms of commonality of vocabulary, Language H seems to be very close to Currier Language A. Language T (except for the "zodiac" section) is similar to Currier Language B. Languages D and E look like hybrids of A and B; C looks like a different language altogether.

The ten most frequent “words” in Currier’s Languages A and B: and in each of the thematic sections. Source: author's analysis.

Correlations and mappings

My idea of the next step is to correlate the frequencies of the glyphs in Languages H and T with the frequencies of the letters in some presumed precursor languages (for example, medieval Italian and medieval Latin). Then it should be possible to match vowel-glyphs with vowels, and consonant-glyphs with consonants, and thereby transliterate selected pages of the Voynich manuscript into the precursor languages.

If this process yields some recognisable words in, say, Latin or Italian, we might be on the right track. If not, there are several permutations of the approach, for example:

In these tests, I used Dr Mans Hulden's Python code for implementation of the algorithm.

The transliteration of the Voynich manuscript was one of my own devising, which I designated v211. It is one of the latest in a series, each of which is based on Glen Claston's v101 transliteration. It differs from v101 in the following principal respects:

* I used exclusively lower-case letters and Unicode characters.As illustrated below, these experiments seemed to identify a consistent set of vowels for the herbal section, and another broadly consistent set of vowels for the text-only, text-with-stars, cosmology and zodiac sections.

* I introduced the concept of position-dependency: specifically, for glyphs 1, 9, a and o, I used different Unicode characters depending on whether the glyph was in the initial, interior, final or isolated position.

* I combined groups of glyphs which are visually similar, for example the v101 glyphs 6, 7, 8 and &.

* I assumed that the v101 glyph 2, and its variants, were equivalent to the v101 glyph 1 with various accents (which may have several meanings, but which I have provisionally lumped together).

* I disaggregated several v101 glyphs which seemed to me to be strings of glyphs, notably m, M and n which seemed to contain embedded instances of the glyphs i or I.

Applications of the Sukhotin algorithm for the identification of vowels, to my v211 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. Source: author's analysis.

I provisionally designated the language of the herbal section as Language H (which is very similar to Currier’s Language A); and that of the text, cosmology and zodiac sections as Language T (which has several probable vowels in common with Currier’s Language B). The biology, pharmaceutical and astronomy sections seem to be in different languages from either A or B.

Vocabularies

Different languages have different vocabularies. But European languages, even if not closely related, have some words in common. Below is a compilation of the ten most frequent words in selected medieval European languages. We see that there are five common Latin words - de, et, in, non and per - which reappear as common words in other European languages, although pronounced differently.

The ten most frequent words in medieval Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, German, Italian and Latin. Source: author's analysis.

If the Voynich manuscript has European precursor languages, and if we have evidence of different precursors for Currier A and B, and for the thematic sections, then we should expect to see some differences and some commonalities in the vocabulary between A and B, and from one section to another.

Accordingly, we assembled data on the counts of the 20 most frequent "words" in Currier Language A and B, and in each of the thematic sections.

In terms of commonality of vocabulary, Language H seems to be very close to Currier Language A. Language T (except for the "zodiac" section) is similar to Currier Language B. Languages D and E look like hybrids of A and B; C looks like a different language altogether.

The ten most frequent “words” in Currier’s Languages A and B: and in each of the thematic sections. Source: author's analysis.

Correlations and mappings

My idea of the next step is to correlate the frequencies of the glyphs in Languages H and T with the frequencies of the letters in some presumed precursor languages (for example, medieval Italian and medieval Latin). Then it should be possible to match vowel-glyphs with vowels, and consonant-glyphs with consonants, and thereby transliterate selected pages of the Voynich manuscript into the precursor languages.

If this process yields some recognisable words in, say, Latin or Italian, we might be on the right track. If not, there are several permutations of the approach, for example:

• To use a different transliteration: that is, to redefine the glyphs. For example, in v211 I assumed that initial o, interior o and final o were different glyphs (or, more precisely, represented different precursor letters). We can recombine them.One further permutation which I am exploring is to consider that the precursor documents were in abbreviated languages. Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon Abbreviaturarum encourages us to conjecture that the Voynich initial 9 and final 9 are abbreviation symbols (and with different functions). To this end, I developed an abbreviated version of Dante’s Monarchia (1313-14), with the following substitutions:

• To swap some pairs of glyphs which have similar frequencies. For example in the herbal section, interior o is the most common glyph, accounting for 8.9 percent of all the glyphs, followed by final 9 with 8.6 percent of the glyphs. That might encourage us to map interior o to the most common letter in the precursor language (E in Italian, I in Latin). But within a given language, the letter frequencies differ from one document to another. Dante’s La Divina Commedia does not have exactly the same letter frequencies as the OVI corpus. So we have to allow ourselves flexibility in the glyph-to-letter mapping.

• To try other precursor languages. (So far, I have looked at Albanian, Bohemian, English, Finnish, French, Galician, German, Hungarian, Icelandic, Portuguese, Slovenian, Spanish, Turkish, Welsh and other languages, and in each case calculated the letter frequency distributions in selected medieval documents.)

• initial 9 (₉) for the prefixes co-, com-, con-, cum-, cun-This transforms, for example, the following line of Monarchia:

• final 9 (⁹) for the Latin suffixes -is, -os, -us, -um, -em, -am.

• from: “non tam de propria virtute confidens, quam de lumine largitoris”I have calculated the symbol frequencies in the abbreviated Monarchia and will see how they match up with the Voynich glyphs. More later.

• to: “non t⁹ de propria virtute ₉fidens qu⁹ de lumine largitor⁹”

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers