Voynich Reconsidered: filtering the languages

In my new book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), I have outlined a strategy whereby the interested reader could pursue his or her own ideas as to the underlying meaning of the mysterious Voynich manuscript. In recent articles on this platform, I reported some results of a specific strategy for identifying the precursor languages of the manuscript, or at least filtering the more probable ones. I called it the [8am} strategy.

The strategy is based on a process of mapping selected common “words” in the Voynich manuscript, to text strings in selected medieval languages.

I started with the "word" represented by {8am} in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. This is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript, occurring 739 times.

The first trial mappings yielded some reason to think that {8am} might map to real words in at least four medieval languages, as follows:

The Voynich “words” {8am}, {1oe) and {2c9},

rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image

credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

The {8am} process

For each Voynich "word" to be tested, the process involves the following steps:

As in the first trial mappings, I tested up to thirty-seven different transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all of my own devising but derived from Claston’s v101. The target medieval languages were those that I had selected for reasonable geographical proximity to Italy, where Wilfrid Voynich was said to have rediscovered the manuscript. Initially I focused on Arabic, English, Galician and Italian, which had yielded encouraging results for the “word” {8am}. My team is currently working on other languages.

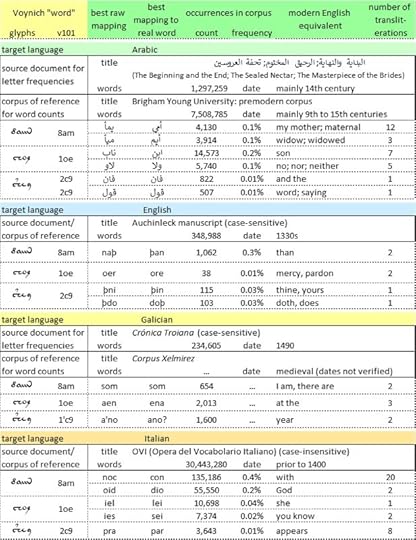

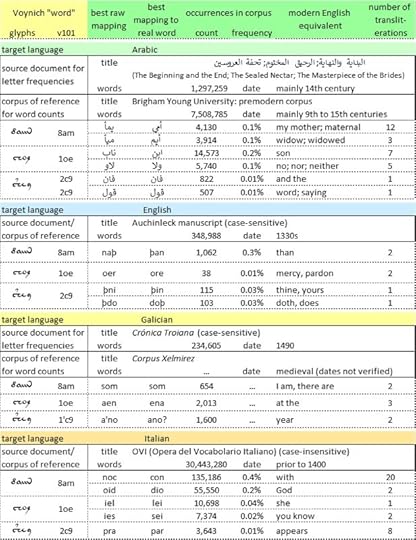

Mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}

To cut to the chase: these tests in most cases yielded mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to real and relatively common words in all four languages:

Selected mappings of the "words" [8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to words in selected medieval languages. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q72NkY

In most cases, it was necessary to re-order the letters in the raw text strings: sometimes, to reverse the order. I felt that this was to be expected, given that, as D’Imperio and Zattera observed, the glyphs follow a rather rigid sequence within “words”. Since I do not know of any such sequencing in natural languages, I was inclined to one of the following views:

Next steps

To my mind, the next steps should be as follows:

The strategy is based on a process of mapping selected common “words” in the Voynich manuscript, to text strings in selected medieval languages.

I started with the "word" represented by {8am} in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. This is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript, occurring 739 times.

The first trial mappings yielded some reason to think that {8am} might map to real words in at least four medieval languages, as follows:

• Arabic as written in the fourteenth century, represented mainly by Ibn Kathir’s البداية والنهاية (The Beginning and the End), a text which I received by courtesy of Dr Mohsen MadiThe next step was to attempt mappings of other common Voynich “words”. For this purpose, I selected the following “words”, which have no glyphs in common with {8am}:

• English as written in the 1330s, represented by the Auchinleck manuscript

• Galician as written in the 1490s, represented by the first printed edition of Crónica Troiana

• Italian as written prior to 1400, represented by the OVI corpus, or Opera del Vocabolario Italiano.

• {1oe}: the seventh most common “word” in the manuscript, occurring 400 times

• {2c9}: the 22nd most common “word” in the manuscript, occurring 209 times.

The Voynich “words” {8am}, {1oe) and {2c9},

rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image

credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

The {8am} process

For each Voynich "word" to be tested, the process involves the following steps:

• testing multiple transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, in permutations with multiple precursor languages;As I reported earlier: my transliterations allow for varying definitions of the glyphs. For example, I have considered the possibilities that:

• for each permutation, mapping the “word” to a text string in the target language, using frequency rankings as the basis for the mapping;

• and for each such string, searching a suitable corpus of the target language for that string as a real word.

• {m} might be not one glyph but two or three, possibly equivalent to {in} or {IN} or {iiN} in the v101 transliteration;Mary D'Imperio's "five states" and Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet" had suggested that the Voynich scribes might have re-ordered the glyphs within "words". In cases where the raw mapping yielded a text string which was not a meaningful word in the target language, I allowed for the possibility of re-ordering or reversing the letters in the text string.

• {1} might be two glyphs, possibly equivalent to {Ec};

• {2} might be a variant of {1}, with a diacritic of unknown significance: possibly a vowel analogous to the dammah (ـــُــ) in Arabic; or a wild card with multiple meanings.

As in the first trial mappings, I tested up to thirty-seven different transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all of my own devising but derived from Claston’s v101. The target medieval languages were those that I had selected for reasonable geographical proximity to Italy, where Wilfrid Voynich was said to have rediscovered the manuscript. Initially I focused on Arabic, English, Galician and Italian, which had yielded encouraging results for the “word” {8am}. My team is currently working on other languages.

Mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}

To cut to the chase: these tests in most cases yielded mappings of {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to real and relatively common words in all four languages:

Selected mappings of the "words" [8am}, {1oe} and {2c9} to words in selected medieval languages. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q72NkY

In most cases, it was necessary to re-order the letters in the raw text strings: sometimes, to reverse the order. I felt that this was to be expected, given that, as D’Imperio and Zattera observed, the glyphs follow a rather rigid sequence within “words”. Since I do not know of any such sequencing in natural languages, I was inclined to one of the following views:

• that the Voynich producer had given the scribes not only a mapping from letters to glyphs, but also an “alphabet” as a basis for re-ordering glyphs within “words”: perhaps something along the lines of Zattera’s “slot alphabet”;In most cases, there were multiple transliterations which yielded the same raw mapping.

• or that, if the precursor language was Arabic, the scribes were unaware (or were instructed to ignore) that Arabic was written from right to left, and had taken the leftmost letter to be the first;

• or that the producer had simply instructed the scribes to reverse the order of the letters within words: possibly as a form of simple encipherment.

Next steps

To my mind, the next steps should be as follows:

• to map some other common “words” in the Voynich manuscript: preferably “words” with some different glyphs from those in the first three, such as {4ohan}, which I am inclined to read as {④han}If this process yields encouraging results, we can contemplate mappings of whole lines.

• to identify, if possible, those transliterations which consistently map the common Voynich “words” to real and common words in one target language or another.

Published on September 23, 2024 00:13

•

Tags:

arabic, auchinleck, cronica-troiana, fernan-martis, galician, ibn-kathir, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers