David B. Williams's Blog, page 16

February 25, 2014

Seattle’s Mammoths, Again

Wow, with all of the press on the Seattle mammoth, you’d think that no one had ever seen a mammoth before. Over the past week or so, news organizations from around the world (NPR, CNN, ABC, Fox, The Guardian, to name a few) have devoted an amazing amount information to our city’s newest media star.

It does make me wonder why. Part of it has to do with misunderstanding. I talked to one of the Burke Museum’s researchers who told me that friends kept asking him about the dinosaur that the museum was unearthing. (Washington is one of the few states where dinosaurs have never been found.) Despite what some people seem to think, mammoths are not dinosaurs, although the extinct pachyderms are very big and charismatic. Mammoths may be one of the few extinct beasts that rival dinosaurs for popularity. Ironically, the museum is supposedly going to put the tusk on display at its annual Dinosaur Day, Saturday, March 8.

A second part is that mammoths have become much more famous through the Ice Age movies, thus when the remains of one, even if it’s just a small percentage of the body, are found, people get excited. There was also the compelling story of the children from Bright Horizons Child Care cheering on the dig with such endearing signs as “Woolly U Be My Valentine.” There are few news items more compelling than tots and tusks.

And finally, Seattleites and the media that follow our fair city have been prepared for subterranean stories, following the brouhaha over Bertha and her lack of movement. Bertha’s troubles have already helped us to learn more about the city’s early history. The mammoth was simply pushing the history deeper into the past. I do hope that the interest in those stories will continue, as many more are waiting to be discovered and told.

I also wanted to point out a nifty blog posting, put up by Dave DeMar, a PhD student in paleontology at the University of Washington. Dave provides some great first hand accounts of the dig. Another Burke researcher I spoke with noted that the dig went amazing well, especially with so many people watching. It speaks highly of the Burke team, as well as the contractors (particularly the person who hit the tusk with his backhoe and recognized that it was something important enough to stop the dig) and those who owned the land. Let’s hope that they inspire others.

February 20, 2014

Keep on Digging in Seattle

Seattle’s subterranean history has become all the rage of late. From mammoths to Bertha, the stories keep cropping up. Since events seem to happen in threes, it makes me wonder what else is lurking just beneath the surface: an earthquake, a sinkhole (like the one that swallowed Corvettes in Kentucky), or more shoes wrapped in Yiddish newspapers? This is the issue raised by the always astute Knute Berger, in a story in Crosscut titled “Could the Bertha boondoggle be a local history boon?”

Berger wonders whether Bertha’s stoppage will lead to new revelations about the city’s history. The machine stopped at an ideal spot, just west of where the city started, and where much debris (or what others call archaeology) awaits discovery. No one expects any Pompeii-like discoveries but by unearthing artifacts such as bottles, shoes, combs, or glasses we start to “paint a more human, intimate picture of the lives people led,” writes Berger.

As someone who is interested in history, I have been asked many times why we should care about the past? For me, it boils down to two reasons. The first is that it provides me a deeper connection to my home and to the people who lived here. As we dig up these artifacts and find items such as a Rainier beer bottle, baby formula, or bottled water imported into Seattle in the late 1800s from Alaska, it’s hard to think that I am so different from those who lived here before. We came here for many reasons and we do many different things but in the end we are really not that different, in wanting a place to live, food to eat, water (or beer) to drink, friends to share our lives with.

The second is that knowing the past of the place I live, makes it more interesting to live here. It gives me a fuller and happier life. This may sound like a particularly nerdy platitude but I know I am not alone in holding this view. Consider how often the subject of Seattle’s past has come up in recent weeks and how often you and your friends have discussed what lies beneath. I really do think that there is a hunger for these stories.

I agree with Berger and hope that those who are trying to fix Bertha, take the opportunity to do some good archaeology on the way down to fixing her. It’s the least they can do and could provide a silver lining for what many consider to be a pretty ugly mess.

February 12, 2014

When Mammoths Walked in Seattle

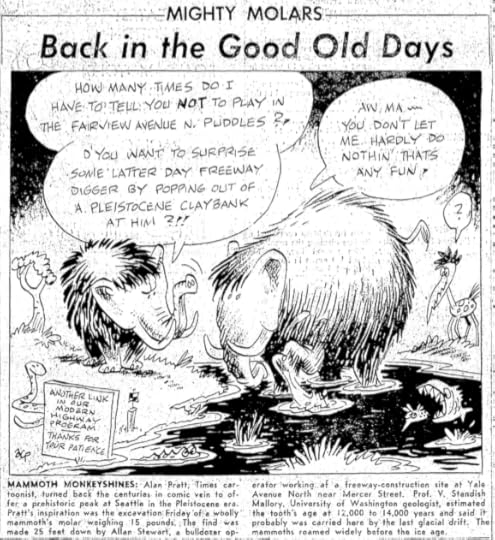

Yesterday, a worker found a tusk in Seattle. The well preserved specimen, most likely from a mammoth but possibly from a mastodon, was unearthed at a site in South Lake Union. After making the discovery, the workers contacted the Burke Museum, which sent a team of experts to examine the site. Unfortunately, they were not able to excavate it, as it is on private land the owner had not yet decided what to do with the tusk.

Based on the initial analysis, Burke paleontologists believe that the tusk comes from a mammoth. If that is the case, it is most likely a Columbian mammoth, as that is the species known from this area. In fact, there have been at least 18 discoveries of mammoth remains in King County. They include tusks, molars, femurs, and various fragments. One of the most recent was found at Lakeview Elementary in Kirkland during the excavation for the school’s gymnasium. At the time, it was reported in the press that tusk was from a mastodon. Subsequent research showed that it was actually from a mammoth. It was also age-dated to 16,540 ± 80 14C yr B.P., or 19,710 calendar years before present, the youngest evidence for mammoths in the region.

No matter what species it is, the tusk is further evidence of the many stories that lie just beneath the surface and that reveal the complex history of the Seattle landscape. I suspect there will be further chapters to come.

From Seattle Times, June 20, 1963

February 5, 2014

What’s Under Seattle

As the state museum of Washington, the Burke Museum is the official repository for many of the wonderful natural and cultural history cultural that have been found or produced in the state. This includes items discovered during the many engineering projects that have shaped Seattle. To help familiarize people with some of the objects, the museum is hosting an event tonight, Thursday, February 6, as part of the city’s First Thursday events. This is the day that many museums in Seattle are free to visit.

The Burke’s event is titled, What’s Under Seattle. My colleague at the museum, Archaeology Collections Manager Laura Phillips, and I will be leading the event. Our plan is to discuss some of the landscape changes in Seattle and to share some of the objects that have been excavated during the excavations. We will also address that giant machine under the city, Bertha, and consider some of the issues that ail her. Hope you can attend.

We will be speaking at 6pm in the museum on the University of Washington campus.

January 4, 2014

Bertha-Oh well

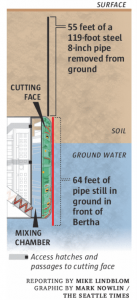

The WSDOT finally fessed up that an abandoned pipe casing is the culprit choking its beloved Bertha. Turns out that contractors were supposed to know that the 8-inch diameter, 119-foot-long well casing was there. Furthermore, the pipe had been placed as part of a study to measure groundwater during research for the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement project.

Berthablocker from The Seattle Times

WSDOT officials stated on Friday that they had hit the pipe on December 3, when Bertha pushed it six to seven feet out of the ground. Workers then pulled up a 55-foot long piece of the pipe, apparently thinking that they had gotten out the entire thing. According to spokesperson Chris Dixon, when Bertha then started to chew up a boulder, it gave them “a false sense of security.”

Several issues stand out about this story. As someone focused on Seattle’s history, I thoroughly enjoyed so many people taking such an interest in the buried stories of our city’s past. I can only hope that people will continue to want to learn more of these stories. As a geologist, I also enjoyed the focus on Seattle’s geologic past, Plus anything that can get more people to say “glacial erratic” is fine by me.

More disturbing though, is the reticence of WSDOT on the pipe casing. In the week after the initial stoppage, a buddy of mine had told me the exact story that WSDOT is now telling. Why didn’t they just tell us immediately? Their excuses now just seem to be self-serving, a particularly bad precedent for an agency known for making a few huge errors. I recognize that they might not have been able to do anything, and all of the fun speculation would not have occurred, but it seems that being truthful certainly wouldn’t hurt WSDOT.

One positive aspect of the pipe story is that as the drill progresses, it will move completely away (at least it is supposed to) from any area where human-created objects could block Bertha. That does not mean that there won’t be any erratics, or other glacially deposited boulders, to get in the way, but at least Bertha was designed to cut through them.

I suspect though that this won’t be the last time Bertha will be in the news.

December 21, 2013

Seattle’s Digging It

“As a result of its rugged topography, the city of Seattle has a class of engineering problems peculiarly its own,” wrote George Holmes Moore. He, of course, was referring to the desires of Seattle citizens to travel more easily through the city. The only solution was to move massive amounts of dirt out of the way and create better access. Holmes’ sentence was written in March 1910. He was referring to what until Bertha bit it, or couldn’t, was Seattle’s most famous digging scheme, the regrading of Denny Hill.

As with Bertha, the removal of Denny Hill at the north end of downtown Seattle was big news across the country. The reports describe the blasting away of 5.5 million cubic yards of dirt as a beautiful thing, necessary to the survival of the city. As H. Cole Estep wrote in Industrial Magazine, “This is a tremendous task for a community so young in years; but the citizens, having an abiding faith that Seattle is destined to become the New York of the Pacific coast, have taxed themselves cheerfully and heavily in order to finance the undertaking.” Sound familiar? All we need to do is a bit of landscape rejiggering and Seattle will be a world class city. It didn’t happen then.

Most citizens did not actually tax themselves. Only those affected by regrade projects had to pay. They did so through what were known as Local Improvement Districts, where those who owned land in the regrade area paid for the project because they were the ones who would benefit the most by the increased value of their post-regrade property. How much each property owner had to pay was determined by a three-person commission, which, as one can imagine, led to a few issues involving the courts.

Those early landscape remodelers ran into a few underground issues too. Their technology of choice was water, using hydraulic hoses, or giants, to wash away the hills. When they encountered small objects, such as buried forests, mammoth teeth, or once, a suspected meteorite that probably was just a boulder, they would stop and pluck it out, but when they ran into more obstinate objects—usually dense lenses of fine grained sediment—they would turn to the old reliable dynamite, blast the offender to bits, and continue remove the dirt. They had it a lot simpler back then.

Despite cost overruns, lawsuits, deaths, and delays, the city completed the major regrade projects, giving Seattle a new face. I suspect that Bertha will eventually get back on track too but it always amazes me how history repeats itself.

And because my momma done told me to, I am including a link to a story in the New York Times about Bertha.

December 19, 2013

Dreaming of Tunnels in Seattle

Bertha and her travails got me thinking about Seattle’s long history of tunneling and tunnel plans. In an article by Red Robinson, Edward Cox, and Martin Dirks, the authors wrote that over the past century or so, “more than 100 tunnels totalling over 40 miles” have been excavated in Seattle. These include sewers, railroads, water lines, landslide stabilization, and busses. The earliest dates back to the 1880s.

What they don’t mention are the numerous tunnels proposed but never built including ones under First Hill, Denny Hill, and Beacon Hill.

Here is a very short list of some of those that were built and those that merely were dreams.

1. Great Northern Tunnel – 1903-1905 – The 5,141-foot-long tunnel allowed trains to bypass Railroad Avenue and drop passengers at the Great Northern’s new Union Depot (later called King Street Station), being built out into the tidelands at the south end of downtown. The tunnel was built from either end, into the center. The crews met on October 26, 1904, Along the way, they had encountered a forest of buried trees. They also had a few troubles, including buildings settling as the tunnel went beneath them. One of them, the York Hotel (also known as the Ripley) sustained so much damage that the Great Northern bought it and leveled it. Seattleites liked to joke that it was the longest tunnel in the world as it went from Virginia to Washington…streets.

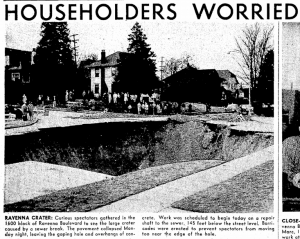

2. North Trunk Sewer -1908-1914 – Prompted by a fears of cholera and typhoid, the city built almost 22 miles of sewer tunnel, mostly in the northend, including one of the longest sections, the 3,500 tunnel under Ravenna Creek from its former outlet at Green Lake to the University Village. Workers started with a shielded boring machine but it was not able to cope with the soil conditions so ultimately the tunnel was dug by hand. The tunnel failed in Novembr 1957, creating a massive sinkhole at 16th Ave. N. and NE Ravenna Boulevard.

Sinkhole on Ravenna in 1957 - from Seattle Times

Tunnels that never made it.

1. Denny Hill Tunnel – 1890 – L.H. Griffiths, developer of Fremont, proposed a tunnel under Denny Hill to make it easier to reach his development. It was stopped though several years later, Thomas Burke, a leading opponent of the tunnel, suggested it should have been built.

2. Jackson Hill Tunnel – 1904 –In early 1904, residents requested the city to excavate a tunnel through Jackson from Fifth to Twelth avenues. After a careful investigation, city engineer R.H. Thomson rejected the idea and convinced proponents that it would be better to eliminate the high ridge.

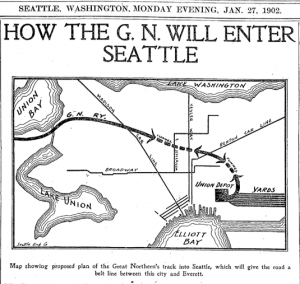

Great Northern through Beacon Hill - From Seattle Times

3. Beacon Hill – 1902 – Great Northern proposes to enter Seattle by tunneling under Beacon Hill.

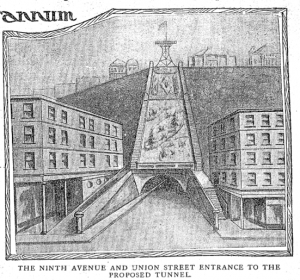

4. First Hill – 1903, 1908, and 1929 – Various groups over the years proposed tunneling under First Hill to access the valley beyond and also to access Second Hill.

First HIll Tunnel plans - From Seattle Times

5. Bogue Tunnels – In 1911, engineer Virgil Bogue presented a grand transportation and city plan for Seattle. His proposed tunnels included Day Street in southeast Seattle, and ones under parts of First Hill, West Seattle, Interlaken, Spokane Street, and Blanchard Street, as well as railroad tunnels under Beacon Hill, Wedgwood/View Ridge, and downtown Seattle.

December 14, 2013

What Bertha Could Have Hit – BerthaControl

With all of Seattle baffled by Bertha, and the answer to what’s stopping her apparently not forthcoming any time soon, I thought I’d look at a few known features that lurk below the city surface, and that Bertha could have it if she turned the wrong turn. I learned about these items while researching my new book, Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

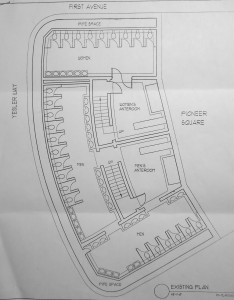

1. The Queen Mary of Johns - Called by some the most luxurious underground toilets in the world, this public restroom opened in 1909, directly under Pioneer Place. Built to accommodate 10,000 flushers a day, it had stall walls of Alaskan marble, with terrazzo and white tile covering the floor and walls. There were ante-rooms for men and woman with oak armchairs. For dime you could get your shoe shined. Men could also buy cigars. Air was ventilated through pipes built into the elaborate structure we call the Pergola, which was designed to make the restroom below cleaner and brighter.

After the restroom opened, an article in the Pacific Builder and Engineer opened with the following statement. “The man of travels will find nowhere in the Eastern hemisphere a sub-surface public comfort station equal in character to that which has recently been completed in the downtown district of Seattle; and in the United States there are very few that will be found to equal it.”

The restroom has been closed for years, though periodically people try to reopen it.

BerthaControl – Four – Bertha wasn’t designed to go through porcelain toilets so she might have gotten clogged up here.

Plan of the Can

2. The Windward – On December 30, 1875, the 161-foot-long, three-masted ship Windward ran aground in the fog on Whidbey Island’s Useless Bay carrying a load of lumber bound for San Francisco. James Colman then acquired the ruined ship (the owner owed him $800) and had it towed to Seattle, where it was beached on the shorefront. By 1887, when a railroad trestle was being built across the waterfront, the ship had become a husk with all valuables stripped away and no masts. Today, the hull sits where Colman left it on the waterfront, buried somewhere under modern pavement. The best guess is in the vicinity of the corner of Western Avenue and Marion Street, though no evidence of the Windward has appeared in any recent building projects.

BerthaControl – One – Bertha would have whipped through this in no time.

The Windward - From UW Libraries

Photo from UW Special Collections

3. Coal Cars in Lake Washington – In the 1870s, coal was starting to become an important export from Seattle. To get the coal to Seattle from its source near modern day Newcastle, it was ferried across Lake Washington to the land separating Lake Washington and Lake Union, portaged across this divide, put back on a boat to cross Lake Union to a terminal, where Seattle’s first train carried it down to a coal bunker at the base of Pike Street. In January 1875, a small stern-wheeled steamboat, the Chehalis, was making the run across Lake Washington when a storm tipped the barge carrying 18 railroad cars full of coal. The cars were discovered by Robert Mester. They sit in the middle of the lake, a bit south of the 520 floating bridge.

BerthaControl – Three – Steel, wood, and coal would have slowed down Bertha, though probably not for long.

Coal Cars

Photo from Emerald Sea Photography web site

4. Submerged Forests – Around 1,100 years ago, three groves of trees slid into Lake Washington. The trigger was an earthquake on the Seattle Fault, which runs from the eastern edge of Bainbridge Island through the Duwamish tidal flats and under Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish. The forests now sit in 90 feet of water. One stand is off the southeast corner of Mercer Island. Another settled on the west side of the island, across from the south end of Seward Park, with the third landslide between Holmes Point and North Point near St. Edward Park, north of Kirkland.

When divers explored the trees in 1957, they discovered that many were still upright and appeared to have slid to their present position with little movement relative to the soil where they had grown. The largest had a circumference of over 28 feet and the longest measured 120 feet with a 5.5-foot diameter. They were so waterlogged that they sank readily.

After the Lake Washington Ship Canal opened in 1916, the Army Corps of Engineers had to blow up some of the trees because their tops were too close to the surface; the Corps worried that boats might run into the trees.

BerthaControl – Three plus – These are some big old trees dense with water, plus it’s unclear if Bertha was designed to deal with spongy stuff.

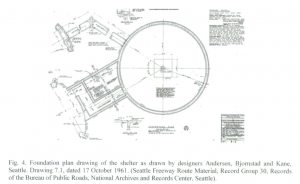

5. Weedin Place Fallout Shelter – During the height of the Cold War in 1963, the federal government paid for a nuclear fallout shelter to be built under I-5. An article in the Fall 2011 Journal of Northwest Archeaology (vol. 45, no. 2) by Craig Holstine describes it as a “prototype community” shelter “virtually bereft of style, designed for survivabilty rather than elegance or comfort.” Planned to hold 200 people for two weeks, it had diesel-powered electricity generator, an air circulation system, a well, and piping connecting the shelter to the city’s water and sewer systems. Beds were triple-level bunks divided by sex and/or family. Holstine also notes that the shelter was later used for storing records from the Washington Department of Transportation and for issuing drivers licenses. The shelter is located on Weedin Place, just north of the Ravenna Park and Ride.

BerthaControl – Five – If the shelter could stop nuclear fallout, surely it could stop Bertha.

Plan of Weedin Place Fallout Shelter

Drawing from Journal of Northwest Archaeology

December 12, 2013

What’s Blocking Bertha

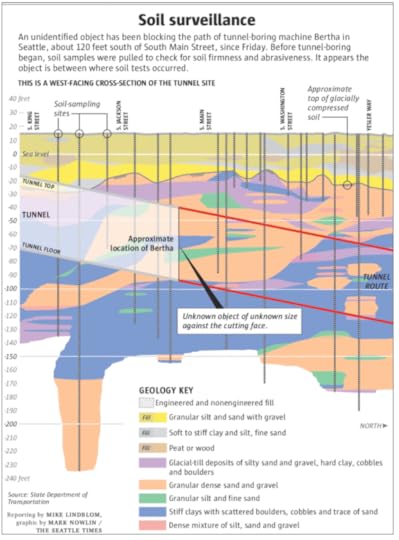

The biggest news of late in Seattle is Bertha and what’s stopping the multi-million dollar drill from its appointed task of cutting a tunnel deep under Seattle. Last Friday, the big borer hit an unknown object that the 57.3-foot-diameter cutting face couldn’t get through. This completely surprised everyone because Bertha was designed to chew through concrete and break up and crack large boulders. Plus, surveys showed nothing was in her path. Yet, just 1,000 feet in and 60 feet underground, Bertha sits still, waiting for her handlers to figure out what is up.

Of course, speculation has been rife as to what is the Berthablocker. Reflecting the city’s other passion, the leading candidate in a Seattle Times poll is a guy who plays for the Seattle Seahawks, followed by Jimmy Hoffa, Seattle’s soon to be former mayor, the eminent Tolkien subterranean beast, Balrog, and Cthulhu, a mythical character created by H.P. Lovecraft. More realistic ideas include Ballast Island (a small bit of land created by ballast dumped from ships docking at wharves in early Seattle); a large, glacial derived boulder; well-casing; or trash dumped during the many years of filling in the Seattle waterfront.

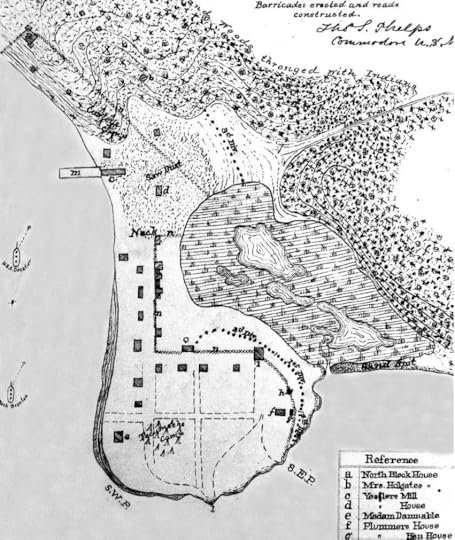

The area where Bertha stopped is an historically interesting spot; it is under what was the southern most point of land in what would become Seattle. (It’s also below the location of Seattle’s most notorious early whorehouse.) When Seattle’s founding families arrived on the eastern shore of Elliott Bay in 1852, the area around what is now South Jackson and South Main streets was a high mound of land, which would become an island at very high tides. (Some call this Denny’s Island, though Maynard’s Island or Maynard Point are more appropriate because Doc Maynard was the first person to own this land.) Behind the mound was a lagoon or salt marsh, which the early settlers—primarily Henry Yesler—filled in with sawdust and other detritus.

Over the decades, Seattelites would fill in the area around Maynard Point, eventually expanding out to include all of the tideflats of the Duwamish River. Initially, as happened with Yesler, the early settlers used what was on hand, which meant trash. When archaeologists dug into the route of the Alaskan Way Viaduct they found bricks, chunks of coal, old logs, pilings, lumber, plates, bottles of Rainier beer, sawdust, slag, charcoal, bones, concrete, and clothing, to name a smattering of items. They also know the location of Ballast Island, which is in the correct area but is apparently not deep enough to block Bertha. (There is also an old boat, the 161-foot long, three-masted Windward, buried in the fill but it is north of Bertha’s blocker.)

Over the decades, Seattelites would fill in the area around Maynard Point, eventually expanding out to include all of the tideflats of the Duwamish River. Initially, as happened with Yesler, the early settlers used what was on hand, which meant trash. When archaeologists dug into the route of the Alaskan Way Viaduct they found bricks, chunks of coal, old logs, pilings, lumber, plates, bottles of Rainier beer, sawdust, slag, charcoal, bones, concrete, and clothing, to name a smattering of items. They also know the location of Ballast Island, which is in the correct area but is apparently not deep enough to block Bertha. (There is also an old boat, the 161-foot long, three-masted Windward, buried in the fill but it is north of Bertha’s blocker.)

What there is little of, though is Denny Hill, which was leveled between 1898 and 1931. One of the great myths of Seattle is that the spoils of the former Denny Hill went to fill in the tideflats or to make Harbor Island. Of the roughly 10 million cubic yards of dirt washed off and scooped out of Denny Hill, no more than perhaps 100,000 to 150,000 cubic yards ended up as useful fill along the waterfront, and very little of that went into the tideflats and none into Harbor Island.

Looking at a cross section profile provided by the Department of Transportation (and redrawn for the Seattle Times), Bertha does not appear to be in any of this fill. Instead, she is in the sediments deposited by the 3,000-foot-thick glacier that plowed through Seattle around 15,000 years ago. Most of this material is sand or clay, derived from the glacier’s grinding the landscape to bits. But the glacier also ferried along boulders of various sizes, known as erratics. Seattle’s most famous is the Wedgwood Erratic, though others still persist and many other were blown up by settlers. (Plymouth Rock is the most erratic.)

So what is blocking Bertha? It seems that an erratic of some sort is the most likely source but there is always the possibility that some unnatural object is down there. During the early years of Seattle, the landscape was constantly being manipulated through projects large and small. Someone could have sunk some sort of shaft or item for an unknown reason. At this point, we can only wait to see what the Department of Transportation finds. Personally, I do hope it is not an erratic; it would be great to find some new mystery down there.

December 6, 2013

Golly ned, that’s a big Cairn

My pal Dave Tucker sent me this great shot of a new cairn. Here’s what he told me.

“The City of Bellingham recently completed a new roundabout at the intersection of S. State, Wharf, Forest, and Boulevard. They placed a large cairn in the center [lit at night]. The bottom two, and uppermost, rocks are dunite, presumably from the Twin Sisters. The second to top is serpentinite. The stones are balanced and are about 12′ feet tall- somewhat foreshortened

in this photo.”

Way to go Bellingham.

One Big Cairn