David B. Williams's Blog, page 15

August 29, 2014

Building Stone Tours

For several years I have given tours of Seattle’s building stones. Now, I am trying something new. I am offering the tours through Groupon/Sidetours. Sidetours advertises itself as “Do Something Memorable.” They offer tours with experts in a variety of locations. Mine is one of many in Seattle. Here’s more information on my walks.

The tour is available on the following dates and times.

September 13 – 10AM to Noon

October 11 - 10AM to Noon

October 17 - 10AM to Noon

October 18 - 10AM to Noon

August 27, 2014

Beware Weyerhaeuser

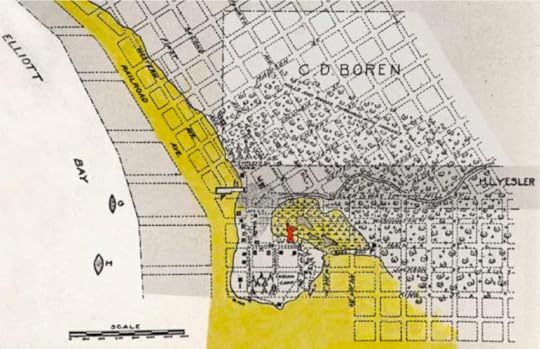

Media outlets around the region are trumpeting Weyerhaeuser’s plan to transfer its headquarters from its 430-acre Federal Way campus to what is now a parking lot adjacent to Occidental Park in Pioneer Square. The move may be wise from a financial aspect but the forest industry giant should be cautious because their chosen location is not the best building site. When the first settlers arrived in Seattle in 1851, the proposed building site was a tidal marsh, covering about eight acres. It was situated just behind a mound of land, where the first houses were built. You can see the marsh in this early Seattle map, modified from Paul Dorpat’s web site. The building site is at the red X.

The marsh was one of the first areas altered in Seattle by the settlers. Legend holds that one infamous land reshaper was “Dutch Ned,” who either wheelbarrowed or toted on his back sawdust from Henry Yesler’s mill and dumped the material into potholes and other less than solid spots. As you might imagine, sawdust isn’t the best subsurface to base one’s foundation upon. It has a tendency to rot and decay, creating voids and soft spots. One of the best places to see this is to go to the parking lot where Weyerhaeuser plans to build. Look at the cars. They are not exactly what one would call parked on level terrain. In some places, they are at relatively steep angles, at least relative to what one might expect in a parking lot.

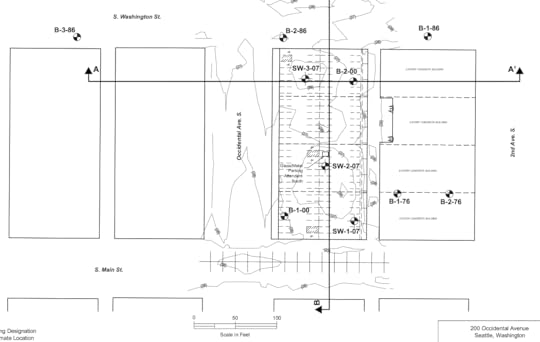

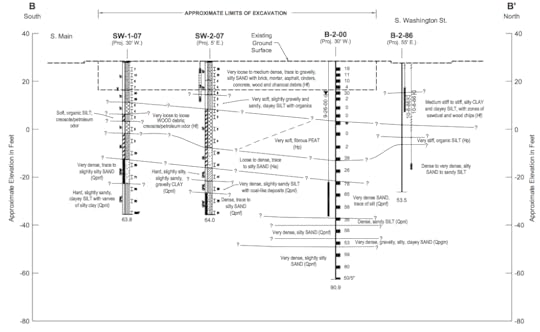

Another way to see what lies beneath is core samples. It’s not a pretty site down below. “Zones of sawdust and wood chips.” “Brick, mortar, asphalt, cinders, concrete, wood and charcoal debris.” “Very loose to loose WOOD debris; creosote/petroleum odor.” Basically, what one finds is the detritus of bygone history: the remnants of the Great Fire of 1889, Dutch Ned’s dumpings, and perhaps collections of garbage from early residents and industries.

Of course, none of this means that the new Weyerhaeuser headquarters won’t be a solid, well built structure. I am sure they are aware of what they are getting into, or onto. But these cores and early maps do give one pause to consider Weyerhaeuser’s decision to move. Time will tell.

Of course, none of this means that the new Weyerhaeuser headquarters won’t be a solid, well built structure. I am sure they are aware of what they are getting into, or onto. But these cores and early maps do give one pause to consider Weyerhaeuser’s decision to move. Time will tell.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

August 26, 2014

Seattle 1841 – aka Piner Point

Like many people interested in geology, I have had a long fascination with maps, particularly of the places I live. I find it appealing to see how people have portrayed the landscape and how that landscape has changed over time. Beginning today, I plan periodically to post a variety of maps of Seattle. I will start with a pair of maps, including the one that was the earliest to apply a formal name to the area we now call Seattle.

They maps are startling for how completely different they look from the modern city. Obviously, there is no urban infrastructure, or even any sign of humans, though we know that in the Seattle-to-be there was a well-developed Native community, with many longhouses housing several hundred people. But what stands out more to me is the look of the land and what it would take to travel across it. To get from what we call Beacon Hill to West Seattle would require a boat, unless the tide was out and then one could walk across mud flats. To leave the shoreline and go inland would require climbing steep bluffs, unless you slogged up a gully.

Those maps were produced as part of Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Expedition (Ex.Ex.). From 1838 to 1842, Wilkes explored the Pacific Ocean and the South Seas. The expedition reached Puget Sound in May 1841, when Wilkes had Lt. George Sinclair, sailing master of the brig Porpoise, map the area that the expedition would be the first to name as Elliott Bay. (Be patient the large maps are large a take a wee bit of time to show up.)

Curiously, one of the unsolved aspects of the expedition is who was the eponomous Elliott of the bay: the Chaplain J.L., the Midshipman Samuel, or the First Class Boy George. Most modern sources believe it to be Samuel, as apparently J.L. had fallen into disfavor with Wilkes, a notoriously unpleasent leader.

The larger of the two Ex.Ex. maps, Chart of Admiralty Inlet, Puget Sound, and Hoods Canal, Oregon Territory, depicts the land and water from Whidbey Island to Budd Inlet. Elliott Bay is shown, with Duwamish Head labled as “Pt. Rand or Moore.” At the mouth of the Duwamish River, the cartographer has written “Bare at low water.”

The second map is the more interesting one, as it is a close up of Elliott Bay. Pt. Moore is shown, as is Pt. Roberts (modern day Alki Point) and West Point, along with Quarter Master Cove and Tubor Pt., in the area we now call Smith Cove. (Henry Tubor was a seaman on the Ex.Ex.) The other long-abandoned name is Piners Point, for a small bit of land located at the modern day Pioneer Square, which makes it the first official, non-Native name for Seattle. Thomas Piner was a quartermaster for Wilkes, who described him as “a very faithful and tried seaman.” Although Piner’s name appears on no other map of Seattle, Wilkes was more successful in creating extant names with a Piner Bay in Antarctic and Point Piner on Vashon Island.

This more-detailed chart depicts Elliott Bay ringed by conifer-topped, steep-faced bluffs bisected by ravines. Piner Point looks less like a point and more like an island, or high mound, covered in shrubbery. North and northeast of the mound, and below the bluffs, the cartographer has drawn in what looks like a marsh with tufts of plants. The marsh gives way to tidal flats that run south below bluffs around to the mouth of the Duwamish, where two uvula-like bodies of land project north.

Wilkes was none too impressed with Elliott Bay noting “the great depth of water, as well as extensive mud-flats.” He concluded “I do not consider the bay a desirable anchorage.”

Apparently Wilkes’ opinion was not heeded as just a decade later, the first settlers began to arrive. In contrast to Wilkes, they were “thoroughly satisfied as to the fitness of the bay as a harbor.” I will consider a map from this era for my next Seattle map post.

These are some of the stories that work their way into my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

August 20, 2014

Serendipitous Marble Vein – Three on the Third

I recently learned about this serendipitous vein in a marble slab in a downtown Seattle building. I like to think that the worker who placed this slab did it knowingly. It certainly looks that way to me. The marble is Alaskan marble, though it is not in the Smith Tower.

Number Three on the Third Floor

Close up of the number Three

August 19, 2014

What Lies Beneath – Secrets of Lake Washington

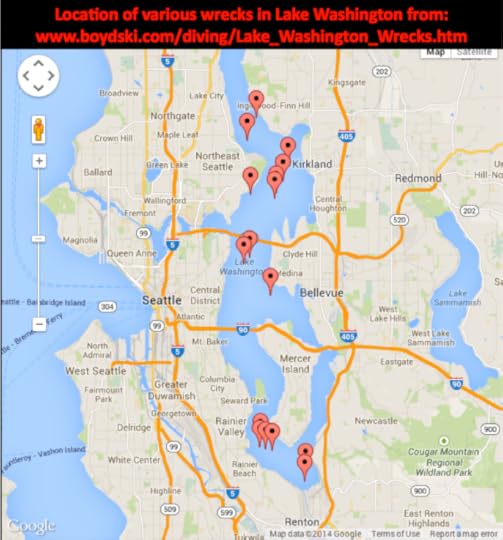

Yesterday, KUOW radio in Seattle played a great story about the treasures at the bottom of Lake Washington. In the story, reporter Sarah Waller went out onto the lake with Mike Racine and Dan Waller, of the Marine Documentation Society. Their goal was target 590, one of more than 800 known treasures at the bottom of the lake, including include planes, trains, and automobiles, as well as three (not two as the story notes) submerged forests and many, many boats.

In writing about the history of Seattle, I have come across stories about several of these buried relicts. I want to highlight three of them.

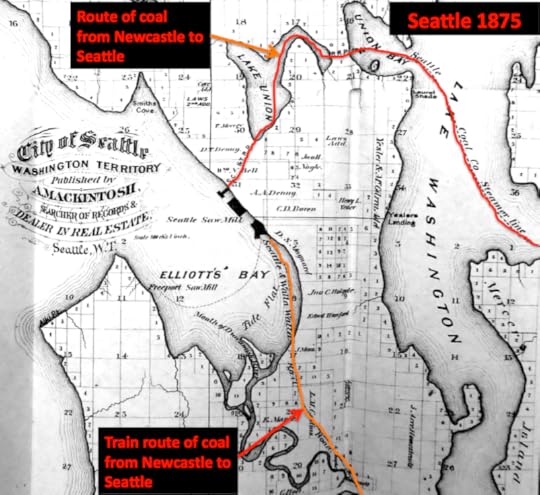

1. Coal cars – Resting in the middle of the lake a bit south of the SR-520 bridge, the coal cars sank during a winter storm, in January 1875. Each car is about eight feet long and four feet high. What makes the cars so interesting to me is not the cars themselves but the story they tell about an often overlooked aspect of Seattle history — that is the importance of coal. In 1868, San Francisco engineer Theodore Blake wrote that the coal deposits near Newcastle, on the east side of Lake Washington, were richer than “any mine yet worked on the Pacific Coast of America.” Unfortunately, there was no easy way to get the coal to Seattle. One route traveled by barge, (which could take up to a week), from Lake Washington, out the Black River to the Duwamish River, and down to Elliott Bay.

On the faster route, the coal was loaded on railroad cars at Newcastle and lowered 900 feet by tram to Lake Washington, where the cars traveled on a barge to Union Bay and then on a tram over the narrow neck of land now crossed by SR-520. A second barge carried the coal cars across Lake Union to a train (Seattle’s first) that carried the coal its final mile to a final tram, which lowered the ore down to a massive coal bunker at the base of Pike Street. It was on one of these trips across Lake Washington that the barge dropped its load of coal cars now sitting at the bottom of the lake.

Seattle's Coal Routes

Finally, in March 1877, train service was completed between Renton/Newcastle and Seattle, which allowed for fast and easy coal transport. With the completion of this route, coal exports from Seattle to San Francisco jumped from 4,918 tons in 1871 to 132,263 tons in 1879, and by 1883, Seattle provided 22 percent of the coal produced on the Pacific Coast. With coal, Seattle was able to stand out from the other small towns around Puget Sound, which relied almost exclusively on lumber. Not only did Seattle gain financially by selling coal and by having coal-related jobs, but it also supplied support services to the developing coal towns, such as goods for workers living at the mines, lumber for buildings, tool shops to build and repair machinery, and a foundry to make rail cars.

2. Submerged Forests – Three submerged forests rest at the bottom of Lake Washington. About 1,100 years ago, an earthquake estimated to be 7.5 magnitude caused the trees to landslide into the lake. The forests consist of several hundred trees, all firmly anchored in soil and either standing upright or tilted at a 45 degree angle. When diver Leiter Hockett explored the trees off Holmes Point (just north of Kirkland) in 1958 he found himself “engulfed in a densely forested bottom.” He was able to bring one tree to the surface, where the wood “although waterlogged [was] as sound and fresh as timber felled on Washington slopes today.”

Submerged Forests Lake Washington

Mostly forgotten, the trees merited public attention in the 1990s. In 1994, John Tortorelli was caught salvaging wood from the submerged forests. Unfortunately for him the state Department of Natural Resources owns the trees, plus he damaged an underwater sewer line. Found guilty of three counts of theft and three of trafficking in stolen property, Tortorelli received a jail term of three and a half years.

3. Steamers and Ferries – The KUOW story noted that there were about 400 boats at the bottom of the lake. One aspect of the Seattle story they illustrate is how the lake used to be crisscrossed by boat traffic in the late 1800s and early 1900s. For much of the history of Seattle and the communities on the east side of Lake Washington, the best, and often only, means of travel was by boat, either self-propelled in rowboats, or via steamboats and paddle-wheel ferries. Most of these boats were locally made or retrofitted at local shipyard. At least 85 steamers worked the lake over the years, functioning as the equivalent of our modern bus system and running regular service to designated spots, usually termed landings, either officially named ones or simply docks where people lived. These landings include long lost names such as Sill, Lucerne, Peterson, Curtis, Northup, Burrows, and Dabney, as well as ones that survived including Newcastle, Mercer, and Medina. Quite a few of the boats sank, including the Falcon, Dawn, and City of Tacoma.

These are some of the stories that work their way into my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

Wrecks in Lake Washington

July 11, 2014

Walk Added

The Seattle Audubon Society has added a second time for the class/walk on building stone that I am leading on August 2. The first walk, at 10am filled. The second walk will be at 1pm and last until 3pm. The walk covers about 1.5 miles as we explore the building stone of downtown Seattle. For more information go to the classes page on the Society’s web site. http://www.seattleaudubon.org/sas/Get...

Some of the building stone we will see.

July 9, 2014

Cairns in Spokane

As many people know, cairns aren’t only found on the trail. Turns out that people near downtown Spokane, Washington, are making them. And the cairns are more than simple stacks of stone. Brick, asphalt, concrete, and stone are turning up in the cairns.

According to an article in the Spokesman-Review, the cairns began to appear a few months ago. At this point, the cairn builders are remaining anonymous. The area is part of a new development in the city called Kendall Yards and the cairns are in a recently graded section. Cat Carrell, who is helping to develop the area with Greenstone Homes told a TV reporter that ”as far as I know the cairns are going to stay until something else happens on that lot.”

June 24, 2014

Save Our Cairns

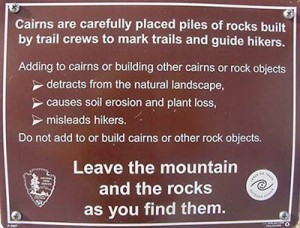

Karen Daubert, Executive Director of Washington Trails Association, recently sent me information about an initiative about cairns in the northeast. The goal is to protect cairns on mountains, as well as to protect the environment where the cairns are built. According to longtime Appalachian Mountain Club volunteer Pete Lane, “Cairns in our area are being damaged and as alpine stewards, we need lots of help to get the word out about leaving them as they are.” As Lane and others involved in the working group note, cairns have long been an essential element of safe hiking in northeast but in recent years these wonderful little piles of rocks have not fared well. The initiative is organized by Leave No Trace.

People not only are destroying cairns but also building too many of them, which can lead people astray and damage the environment, when cairns builders pry up rocks in the fragile alpine ecosystems for cairns. This situation has particularly been bad in national parks and along the Appalachian trail, where people regularly damage cairns despite the best efforts of rangers and volunteers.

The working group has published a set of guidelines for minimizing impact on cairns. Here they are. (From the web site.)

1. Do not build unauthorized cairns. When visitors create unauthorized routes or cairns they often greatly expand trampling impacts and misdirect visitors from established routes to more fragile or dangerous areas. This is especially important in the winter when trails are hidden by snow. Thus, visitor-created or “bootleg” cairns can be very misleading to hikers and should not be built.

2. Do not tamper with cairns. Authorized cairns are designed and built for specific purposes. Tampering with or altering cairns minimizes their route marking effectiveness. Leave all cairns as they are found.

3. Do not add stones to existing cairns. Cairns are designed to be free draining. Adding stones to cairns chinks the crevices, allowing snow to accumulate. Snow turns to ice, and the subsequent freeze-thaw cycle can reduce the cairn to a rock pile.

4. Do not move rocks. Extracting and moving rocks make mountain soils more prone to erosion in an environment where new soil creation requires thousands of years. It also disturbs adjacent fragile alpine vegetation.

5. Stay on trails. Protect fragile mountain vegetation by following cairns or paint blazes in order to stay on designated trails.

All good advice, which is applicable to anywhere you find cairns, whether in the northeast, the Sierras, or the American southwest. With hiking season on us, this another good lesson in how to lessen our impact on the ecosystems we love to explore.

June 19, 2014

Singing Stones

Summer solstice often elicits strange stories about Stonehenge. Now we learn that the builders of the ancient site may have chosen their building material for the simple reason that they were musical, with they meaning both the rocks and the builders. In a recently published article in Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture, researchers Paul Devereux and Jon Wozencroft propose that the bluestones used in Stonehenge were transported more than 125 miles for their acoustical quality. The bluestones, a collective term for dolerites, rhyolites, and tuffs, come from the southwest corner of Wales. The area is known as Mynydd Presell and is famous for the rocky outcrops known as carns.

The study grew out of Devereux and Wozencroft’s work looking at how our senses might have influenced our relationship to landscape. What they found is a visual connection between the natural outcrops and numerous man-made structures, particularly dolmens. When they turned to sound, they discovered that the Welsh bluestone was a “noteworthy soundscape” filled with many ringing rocks. They propose that it is “highly improbable” that the Neolithic stone masons were “unaware of the echoes and the sonic characteristics of many of the rocks around them.” Unfortunately, when they tried to test the bluestones used at Stonehenge they met with little success, primarily because the stones were set in the ground and concrete, which tended to dampen the sounds. Despite this situation, they are hopeful that their work will encourage others to further the study of lithophones, or rocks used deliberately for their sound qualities. For more information, you can read an article in the New York Times.

I was very excited to read this study as I have long been intrigued by the sounds of stone. I first encountered this phenomenon  in southern Utah with the Navajo Sandstone. Walking through the petrified dune field of the Navajo, I periodically came across gray rocks that rang when I stepped on or kicked one. The white or red layers of the Navajo lacked this quality. I eventually found out that the gray layers were ancient playa deposits, preserved as limestone lenses within the sandstone. Like the bluestone, the limestone was very dense. And since the rock often weathers out into boulders, they were in a perfect space to produce sound with plenty of air around them for resonance.

in southern Utah with the Navajo Sandstone. Walking through the petrified dune field of the Navajo, I periodically came across gray rocks that rang when I stepped on or kicked one. The white or red layers of the Navajo lacked this quality. I eventually found out that the gray layers were ancient playa deposits, preserved as limestone lenses within the sandstone. Like the bluestone, the limestone was very dense. And since the rock often weathers out into boulders, they were in a perfect space to produce sound with plenty of air around them for resonance.

Another time I noticed ringing rocks was at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The complex is covered in thousands of three-inch thick panels of travertine, which comes from quarries in Tivoli, about 20 miles from Rome. Best known for its use in the Colosseum, the 80,000-year-old rock is a type of limestone that forms in hot springs. I discovered the sound qualities of the Getty travertine during a visit while I was working on my book Stories in Stone. About half way through my tour, I rapped one of the panels and was startled by its tone. The travertine is very dense but these panels also ring because of how they are mounted. Each panel is bolted about three-eighths of an inch away from each surrounding panel and from its concrete backing. The builders did this so the panels could move when  the next earthquake hits. As with the Navajo, the air space allows the stone to resonate and because every panel at the Getty is different, each one produces a different sound. Pretty cool, I think.

the next earthquake hits. As with the Navajo, the air space allows the stone to resonate and because every panel at the Getty is different, each one produces a different sound. Pretty cool, I think.

Whether the ancient builders of Stonehenge actually chose the bluestones for their musical qualities is not terribly important or life changing. What is important though is that the researchers took the time to observe and to consider the bigger picture of our relationship to the world around us. When we do this, we may not hear songs, but I suspect we will have richer lives.

March 26, 2014

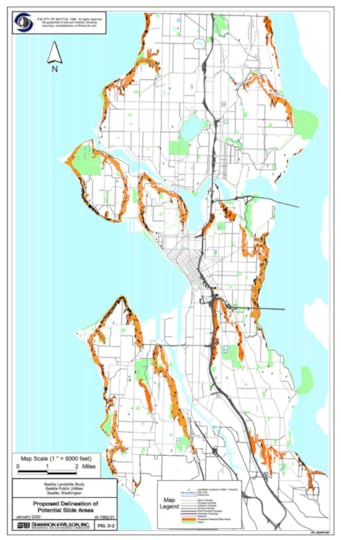

Oso landslide and Seattle

The Oso landslide is a true tragedy, in part because as news reports have noted, study after study showed the dangers of the slope. It was steep, undermined by the river, made of unconsolidated sediments, and further weakened from above by clear cutting, which allowed water to permeate more easily into the hillside. We can only hope that this horrible event will encourage developers, home owners, and government officials to reconsider where they build and to establish more thorough regulations.

As many others have written, landslides are wide spread in this region, including Seattle. This is a fact that has long been known. Consider the letter written on February 27, 1897, by Seattle’s City Engineer Reginald Thomson to Corporation Counsel John K. Brown, the lead attorney for the city. Thomson wrote that landslides had occurred in Seattle “from a time to which the memory of man runneth not back.” The reason had to do with the intraction between a layer of impervious blue clay that lay at the base of the land and pervious glacial drift atop it. When it rains, wrote Thompson, water percolates through the drift “in devious ways” until it reaches the clay below, resulting in a “condition of saturation and suspension” that continues until “the surface ground breaks and settles down.”

Modern geologists refer to Thomson’s drift as the Esperance Sand, a layer deposited 17,400 years ago during the last ice age when a 3,000-foot-thick glacier passed over the region. The clay is known as the Lawton Clay, a rock unit deposited in advance of the sand. As Thomson noted, when it rains water penetrates the sand until it reaches the impermeable clay and in effect lubricates it and makes the slope susceptible to sliding.

[image error]

A "typical" Seattle hill, From Tubbs

Confirming Thomson’s observation, a recent study found that more than 1,400 landslides had hit Seattle since 1890. These included high bluff peeloffs, groundwater blowouts, deep-seated landslides, and skin slides. Skin slides, which are small and can be triggered by intense rainfall, are the most common. Deep-seated events are the most destructive; one of the best known in recent years was on Perkins Lane in Magnolia, when part of the bluff slid and carried several houses down to Puget Sound. The slide occurred in January, by far the worst month for sliding with almost three times more than the next nastiest months, February and March. Not coincidentally, November, December, and January receive the most precipitation.

(When owners of some of these houses sued the city, King County superior court judge Kathleen Learned ruled against them stating: “It is no small thing to re-engineer the basic geology of the region, which is what the Plaintiff’s position would lead to.”)

Usually fairly small and localized, landslides reveal the weak spots in the landscape, the places one might not want to build. This is one reason that green spaces such as Interlaken, Frink, Carkeek, and the Duwamish Greenbelt became parks and not home sites. But we have rewritten the story line, ignoring the historic reluctance to build on clearly less-than-stable slopes. More than 85 percent of the recorded slides owe their slippage to human created problems, include building improper drainage, not repairing broken pipes, chopping off the toes that protect slopes, and imprudent pruning of stabilizing vegetation. Many of the landslides that have hit since 1890 would probably have occurred in geologic time but with human activity we have fashioned a new time scale, one based on human time. In doing so we have made landslides more relevent to the city’s topography and to those who live here.

If you want to find evidence for slides and future slides, go to any steep hillside around the city. Look for areas mostly bare of shrubs or trees, such as the east side of Magnolia above the Magnolia bridge, which slid in 1997; areas rich in springs and seeps, evidence that water has percolated down to the Lawton Clay and is following gravity to the surface; areas covered in alders and maples, trees that pioneer unstable terrain; and areas with askew stairs that look as if they were made by a drunk contractor but which indicate ground movement. (Technically the hill is slumping and not sliding but it is still not a good sign. You can also see this in the tree. On a slumping slope, the trees either till backward or curve up at the bottom.)

Fortunately, the City of Seattle does recognize the high potential for landslides and has developed maps indicating particularly susceptible areas. But then such maps also existed for Oso. We need to do a better job at paying attention. The signs are there. Let’s hope we can learn from Oso.

Landslide zones in Seattle