David B. Williams's Blog, page 13

November 18, 2014

Seattle Map 6 – Lake Washington 1905

The best map showing Lake Washington before the locks and ship canal lowered the lake in 1916 is one produced by the Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1905. Based on survey work done between 1856 and 1905, it shows the topography of the lake shore and the bathymetry. Today, I’d like to focus on one section of the map, which shows the area from Rainier Beach to Wetmore Slough (today’s Genesee Park).

Lake Washington Close Up 1905

In 1870, Joseph Dunlop homesteaded 120 acres along the water at Rainier Beach. Much of it was a swamp, or slough, an excellent place, according to one time resident, A. B. Matthiesen, to lie on a beaver dam and shoot ducks. Rainier Beach High School and its playing fields now cover the lowland. The adjacent Beer Sheva Park, originally Atlantic City Park, was also underwater, and the property east of it, an island, known as Youngs’ Island until Englishman Alfred J. Pritchard bought it in 1900. You can see on the map that a footbridge leads over the slough to reach Pritchards’ eponymous isle and estate, though the island is not labeled.

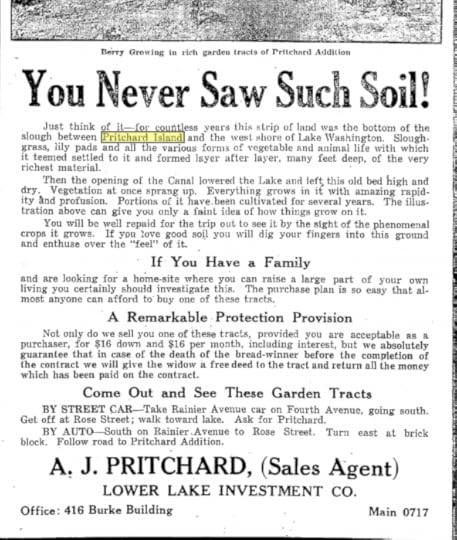

When the lake dropped and the former slough became dry, or at least mostly dry land, Pritchard, like others around the lake, sought to exploit the change. He took out large advertisements in the Seattle Times with the headline “You Never Saw Such Soil!” “Everything grows in it with amazing rapidity and profusion,” touted the ads. All it took was $16 down with $16 per month payments, plus interest.

Pritchard Island 6-18-22

The next noticeable feature north of the island is the Bailey Peninsula, or what we now call Seward Park. The peninsula connected to the main land by a flat wisp of terrain. Harold Smith, who had grown up in the neighborhood in the late 1800s, told a Seattle Times writer in the 1950s that during high water, the peninsula would become an island and the “isthmus could be crossed in a canoe or rowboat.” I doubt that many would call the modern connection to the peninsula an isthmus; it is now wide enough to look like a shoulder, a result of lowering Lake Washington by nine feet.

In 1912, when the Olmsted Brothers were working on their plans for the Seattle park’s system, some locals agitated for a canal through the isthmus so that tour boats could pass through. The steamers would be a boon to “poor people [who] had no means of getting to Bailey Peninsula…without walking a great way,” noted Dawson in a report to the parks on April 5, 1912.

Almost two miles north of Seward Park at Stan Sayres Memorial Park, is another landscape changed by the lower lake level. Labeled as Wetmore Slough on the map, it extended south almost to Rainier Avenue. If you wanted to cross over the slough at the lake, you went on a wood trestle bridge at what is now Genesee Street. The slough drained and for the most part disappeared after 1916 but local residents still complained that it was a source of noxious odors and an incubator for mosquitoes. To combat these problems, the Rainier District Real Estate Association proposed in 1928 to dredge a 200-foot-wide, 2,000-foot-long canal up the old slough, and to make Columbia City into a “seaport town.” Few cottoned on to the dream, though it persisted until 1937 when construction crews began to replace the old trestle with fill excavated from the lake. Six years later the city decided to convert the area to yet another “sanitary fill,” which generated a new round of complaints, this time about dog-sized rats and odors more redolent that ever.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

November 14, 2014

Friday Photo

Golly ned. This photo is a place of superlatives. Deepest. Oldest. Pretty darned coldest. Most voluminous. Plus the Nerpa.

Friday Photo - November 14, 2014

November 10, 2014

San Francisco Regrade-Rincon Hill

San Francisco has long been famed for its hills. There are 43 of them, or 42, or 53, or perhaps even 49, including such well known ones as Telegraph, Nob, and Russian. As happened and still happens in many urban centers, the hills became the fashionable place to live, offering good views and clean air, high above the miasmas that lingered in the lowlands. One of the earliest of these desirable knolls was Rincon Hill, which first attracted the wealthy in the 1850s and by 1861 was described in the Daily Alta California (Feb 2) as “the most elegant part of the city.” But its enviable reputation did not last long.

As James Sederberg pointed out in his fine essay in foundSF, steep hills did not always engender themselves with San Franciscans. One of those hillophobes was John Middleton, a very influential and well-connected resident. Middleton apparently was frustrated that north-south traffic tended to avoid going over the steep edifice of Rincon by taking the low sloped Third Street, thus bypassing property he owned at the base of the hill on Second Street. One way around this problem would be to have the City cut a swath through Rincon along Second Street.

In order to aid the city in their decision-making, Middleton ran for the state assembly in 1867, won, with a little help from his friends, and soon introduced Assembly Bill 444. It authorized a modification of the grade of Second Street for the three blocks between Bryant and Howard Streets. The deepest cut of the canyon would be in the middle, 87 feet at Harrison Street. A bridge at Harrison would connect the two sides of new canyon, with additional steps leading out of the gap.

Not everyone approved of the vivisection of Rincon, including the Alta, which reported this “astounding piece of vandalism was perpetrated …[with] no attention paid even to the most elementary rights of property.” In contrast, an editorial in Chas D. Carter’s Real Estate Circular, which was commenting on a California Supreme Court Case ruling that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors had to allow the cut, noted that the cut would lead to the filling of swamps, as well as having a “beneficial effect upon the extension of Montgomery Street.” (February 1869, v3 n4)

The cut took a year and required 500 men and 250 teams of horses. I have not been able to track down how much dirt was moved though one article in the Real Estate Circular (July 1869, v3, n9, p1) mentioned “120,000 square yards,” which I assume should be cubic yards, as that is how engineers measured these projects. Costing nearly three times more than budgeted, the total cost was about $380,000 with the Harrison Street bridge totalling $90,000.

Despite Middleton’s hopes the cut did not serve its purpose and became an unsavory place frequented by hudlums, leading one writer to note that the only way to pass through the cut was with gun in hand. It was also dangerous as the steeply cut hillsides slid during rainstorms.

One curious aspect of the Second Street Cut, which makes it far different from regrading in Seattle, is that only the street was cut. Properties on either side of the street were not lowered at the same time. Instead, the homes were perched high over the canyon below, which might be nice in a natural setting but was certainly not good in a city. This situation led to the Real Estate Circular calling for the removal of the entire hill: “the space it occupies is required for commerce, and its removal will transform the land from private residence into business property.” (July 1869, v3, n9)

In the end, Rincon Hill became what Robert Louis Stevenson described as a “new slum, a place of precarious, sandy cliffs…solitary, ancient houses, and the butt-ends of streets.” No more hill removal was attempted after this debacle, in part because of the start of the city’s first cable car service in late 1873.

— The most detailed account of the Second Street Cut and its problems is Albert Shumate’s Rincon Hill and South Park: San Francisco’s Early Fashionable Neighborhood, which provided many details for this post.

I would also like to thank LisaRuth Elliott and Chris Carlsson of foundsf.org for their help.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

November 5, 2014

Seattle Map 5: Denny Hill Underwater

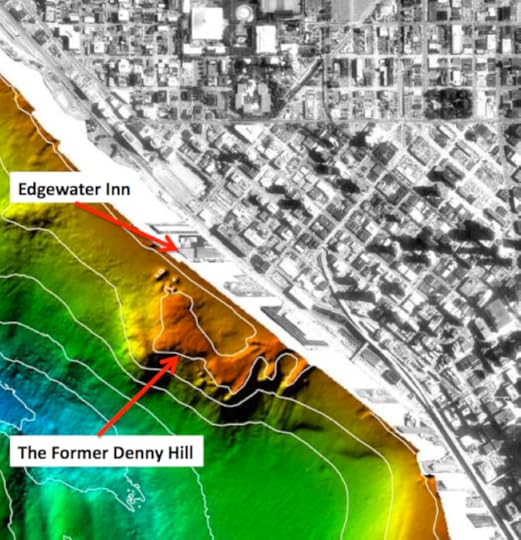

Recently I was standing atop Pier 66 along the Seattle waterfront considering another central tenet of the city’s urban mythology, which is that Denny Hill no longer exists. Conventional wisdom holds that our forefathers eliminated the high mound north of downtown to make way for the coming tide of business. This is not entirely true. Denny Hill still stands; you just need to know where to look. Ask UW oceanographer Mark Holmes and he can show you.

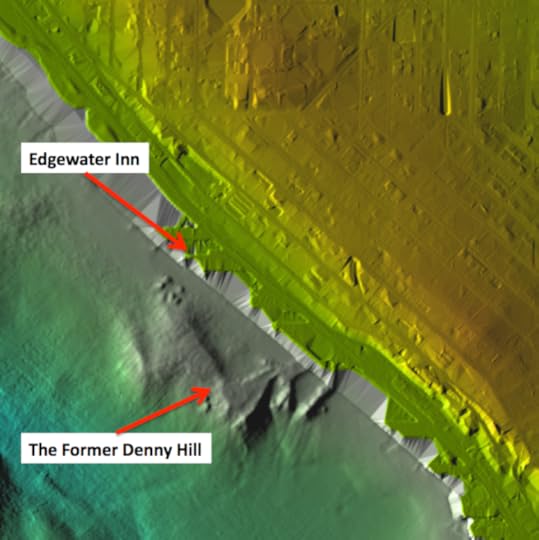

In the summer of 1988, Holmes and two colleagues decided to examine the seafloor of Elliott Bay. The trio wanted to better understand sedimentary processes and their relationship to human made changes in the bay. The earliest map they consulted, an 1875 hydrographic chart, showed that close to shore the seafloor dipped gently and uniformly. When they looked at a map from 1935, they found that the moderate slope was gone, replaced by a shoal, or linear landform “unlike any natural feature” typically found in Puget Sound, says Holmes. The center of the mound was about 500 feet offshore between the Bell Street Pier and the Edgewater Hotel. (Loeffler, Robert D., Mark L. Holmes, Richard E. Sylwester, “In Search of the Denny Regrade: Fate of a Large Spoil Bank in Elliott Bay,” Puget Sound, Oceans ’89 Proceedings, 1989, pg. 84 – 89.)

Denny Hill Underwater - USGS Seafloor Mapping

Hoping to better understand the anomalous landform, Holmes’ team sailed into Elliott Bay on the research vessel Coriolis to run what is known as a seismic reflection survey. Widely used by geophysicists and oceanographers, the technique utilizes sound waves to take a snapshot of layers of underwater, or underground, rock. When the energy pulses bounced back, an array of detectors recorded the data and generated an image of the shoal’s surface and subsurface.

The seismic reflection data revealed a hummocky top, punctuated by an odd, flat-bottomed summit depression. Internally, the shoal consisted mainly of coarse sand and gravel with flanks of clay and silt that sloped steeply to the west. It ranged between 10 to 120 feet thick, measured 1,500 feet wide by 2,500 feet long, and contained an estimated 8.9 million cubic yards of sediment.

Denny Hill Underwater - UW Center for Environmental Visualization

The mound’s shape and texture made Holmes suspect that it was the product of dumping, which the Army Corps of Engineers does regularly into Elliott Bay with sediment from the Duwamish River. Such spoils, however, normally go into deeper sites, where contaminants would have less impact on marine wildlife. As Holmes and his team began to further research the history of Elliott Bay, they realized that they had discovered something more unusual. They had “stumbled into the Denny Regrade” story, says Holmes.

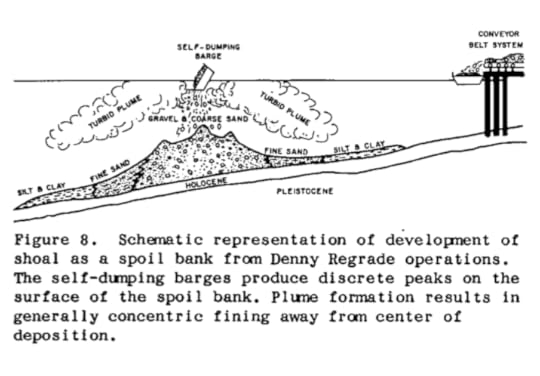

How Denny Hill ended up in Elliott Bay

They learned that most of Denny Hill, the high mound that had stood at the north end of downtown and which was leveled between 1898 and 1931, ended up in Elliott Bay, carried out by a sluice during the initial periods of regrading and later by self-tipping barges. Conspicuously, the total sediment removed from the hill corresponded to within ten percent of the shoal’s volume. Holmes’ team accounted for the difference by landslides on the steep faces, which carried material deeper into the bay. And the odd summit flat spot? Apparently a boat had run into the mound, and dredgers had had to go out into the bay and flatten the boat-damaging, high point.

In Holmes’ mind, they had clearly found the long forgotten remains of Denny Hill. After more than a half century, the famous mound had been rediscovered. It had not been eliminated, it had just been displaced.

I know it’s a bit of a stretch to write that Denny Hill still stands but the submarine mound in Elliott Bay is the lone topographic remnant of the famous knoll that formerly stood at the north end of downtown Seattle. By rediscovering the regraded hill, Holmes and his fellow researchers have provided a direct link to Seattle’s greatest attempt to better the city through reshaping its topography.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

October 24, 2014

Bertha and her problems again.

What? More problems with Bertha and her subterranean homesick blues? Yesterday, we learned that a shell deposit had been found in Bertha’s repair hole. At present, the archaeologists working the site don’t know if its archaeological or geological. Both are a distinct possibility and could even be interfingered.

Part of the problem is that the waterfront was such a dynamic environment. The Native people of the region used it for hundreds to thousands of years and could have left a huge variety of materials behind. An archaeologist I know who studies middens told me once that she had found anything from bones to fecal matter to tools to building materials to you name it in middens around Puget Sound. When European setters arrived, they did the same thing, that is they used the waterfront for a wide variety of reasons, which led to a whole lot of material getting dumped down along the shoreline. And then there’s the constant tide action, which could have reworked and moved around the human deposits, as well as any geological material, such as the shells reported to be in the hole.

Digging the hole to fix Bertha - WSDOT Cam

As Knute Berger writes in his Crosscut piece, the dig will be stopped until archaeologists can figure out what’s down there. They don’t expect to find anything truly exciting, or what Berger calls a “Pioneer Pompeii,” but they know that the potential for Native remains and artifacts does exist. Curiously, they did not expect to find anything at this point. Their earlier test drilling had revealed little, though they did find material from Ballast Island. That’s one of the problems with test holes, they don’t tell the whole story as well as a full excavation.

No matter what happens, Bertha is helping to reveal the complexities of our city and how we have altered its face over time. I suspect that she will continue to provide us with more stories in the months to come, whether WSDOT likes it or not. At least they are looking for them.

October 22, 2014

Stories in Stone Interview on TV

Yesterday, mid-afternoon, I got an email asking me to be on the local NBC affiliate, KING5TV, to talk about building stone and my walks with Sidetour/Groupon. Today, I was on the show, New Day Northwest, for an interview with host Margaret Larson. I had fun. I hope she did too.

Here’s the link to the online version of the interview.

October 21, 2014

Seven Hills of Seattle

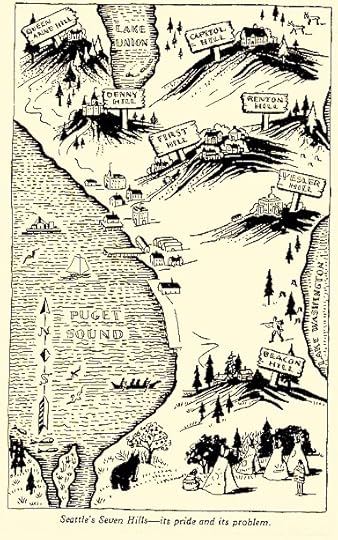

“Seattle’s hills have been its pride and they have been its problem; they have given the city distinction and they have stood in the way of progress,” wrote Sophie Frye Bass in her 1947 memoir, When Seattle Was a Village. As the granddaughter of city founder Arthur Denny, Bass was in a good position to witness the early history of Seattle and her book is often credited with popularizing the sentimental notion that Seattle was built on seven hills, just like ancient Rome.

Seven Hills Map - Sophie Frye Bass

I have heard this topographic claim for as long as I can remember. During my youth, I liked the sound of it; I thought the comparison gave the city an air of distinction. As I matured and became more skeptical, I began to question the details—hills seem to be everywhere—and wondered if some early marketer had invented the idea. Besides, I now view the world through my geocentric eyes and have to look for a more coherent story of Seattle’s underlying topography so I have decided to try and test the theory of the seven hills. Had I been misled as a youth or did we share this hilly quirk with that other city well known for its espresso? And which of our many knolls were the magical seven?

My initial task of naming the seven seemed simple, but proved more challenging than I expected. Friends and family said they had heard the claim but few agreed with Bass, who listed Beacon, Capitol, Denny, First, Queen Anne, Profanity, and Renton. Bass’ first five made most lists but only my mom had heard of Profanity and Renton, also known as Yesler and Second, respectively. Some pinned their hopes on Magnolia and West Seattle, but others favored Mount Baker Ridge, Phinney Ridge, Sunset Hill, or Crown Hill. One overachiever even declared that Seattle is blessed with fifteen hills.

I also talked with someone who questions the entire debate on the seven hills. The late Brewster Denny, a family friend, was Arthur Denny’s great grandson. He expressed a good natured bias toward his aunt telling me, “I don’t see what the controversy is, Sophie was right.”

Whether right or not, Aunt Sophie was not the first to call attention to the hilly heptad. One of the earliest mentions that I could find of seven hills came from the November 6, 1904, issue of the Seattle Times. One Mrs. M.A. Hardy wrote of Seattle “The morning dawns across the waves, At last my eyes can see, The longed for haven of my dreams. The city by the sea, (Like Rome upon her seven hills/In power and grandeur dressed). Like many early histories, articles, and personal reminiscences, Mrs. M. A. Hardy’s poem cited only Seattle’s topographical plenitude, and did not name an ideal seven.

The 12 Hills of Seattle

These early voices mostly moan about the problems associated with hills. For example, two early engineers thought that people shouldn’t have to trouble themselves with walking. Instead, they proposed escalators to ferry people and beasts up the slopes. Then there’s legendary City Engineer Reginald Thomson, who thought that the best idea was simply to level the damned things, though being a truly religious man, I doubt he damned them.

Early citizens may not have cottoned on to romantic notions of rocky knolls offering scenic views of majestic mountains, but by Aunt Sophie’s time it had become a raging issue. A letter to the Seattle Times on March 13, 1950, asking for names of the fabled seven, prompted a rain of responses. Hill advocates listed anywhere between five and ten hills, including long lost favorites Dumar, Boeing, Nob, and Pigeon Point. Adding a ray of government clarity, the City Engineering Department officially recognized 12 hills. They included Sophie’s original seven plus West Seattle, Magnolia Bluff, Sunset, Crown, and Phinney Ridge.

For most modern Seattleites, West Seattle and Magnolia have moved into the pantheon of seven, substituting for Profanity and Renton. Some local historians quibble with these two because Magnolia did not officially become part of Seattle until annexation in 1891 and West Seattle until 1907. Despite this “technicality” and the fact that Denny has been regraded to a mere blip, conventional wisdom now lists Beacon, Capitol, Denny, First, Magnolia, Queen Anne, and West Seattle as the Seven Hills of Seattle.

If you want to see the city’s homage to the Seven Hills, you can visit Seven Hills Park on Capitol Hill.

This story on Seven Hills appeared in a different form in my book, The Seattle Street Smart Naturalist.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

October 17, 2014

Friday Photo: Where Hills Go to Train

Okay, silly photograph today. Saw this and wondered if it was the place where hills go to learn about becoming mountains. I know it’s humor at its lowest level, but that’s what makes it fun. Here’s wishing that whatever attempts at humor you hear/see later today get better. Happy Friday.

Training for Hills

Friday Photo: Where Hillls Go to Train

Okay, silly photograph today. Saw this and wondered if it was the place where hills go to learn about becoming mountains. I know it’s humor at its lowest level, but that’s what makes it fun. Here’s wishing that whatever attempts at humor you hear/see later today get better. Happy Friday.

Training for Hills

October 14, 2014

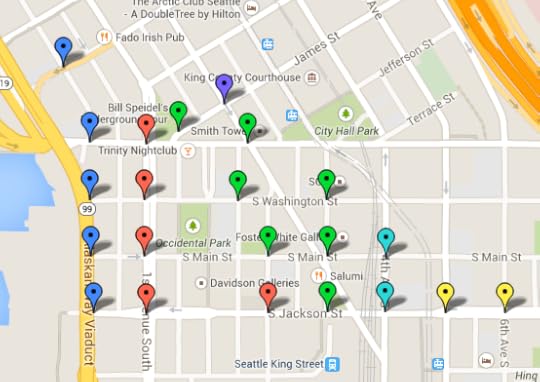

Seattle Map 4 – Downtown Catacombs

On November 14, 1960, the Seattle Times ran a story about the “almost forgotten ‘ghost town’” under downtown Seattle. Entering through the kitchen of the B&R Restaurant at 105 1/2 Yesler Way and equipped with a flashlight, reporter John Reddin and Fire Chief William Fitzgerald descended two flights of stairs into a dim and dusty cavern. They found a series of passageways and old store fronts, as well as old wooden columns.

A week later Reddin went down under again, this time in Seattle’s original Chinatown around Washington Street and Second Avenue. Beneath the streets was a warren of “secret hallways and passages…so intricate in their windings that they were confusing even to the Chinese who entered,” according to an April 3, 1928, Times article. There supposedly was also a secret room only accessible by unlocking a latch that required putting a wood match in a concealed pinhole in a wall. Reddin never found the hole but in a subsequent story he reported on the Merz Sheet Metal Works at 208 1/2 Jackson. (I like the sort of Harry Potteresqueness that so many of the underground spots have that 1/2 added to the address.) Curiously, the shop was 14 feet below the modern street. Outside the subterranean shop one could still see the original sidewalk.

Most people know about these underground passages through Bill Speidel’s Underground tour, but what they may not know is that the tour barely scratches the subsurface of these passages. In addition, the city monitors all of these spaces, or what they call “areaways.” The areaways developed after Seattle’s Great Fire of June 6, 1889, when the city council replatted the downtown area. In particular, they called for the expansion of Second and Third by taking 12 feet from each side, which would make these thoroughfares 90 feet wide. Front and Commercial would also grow from 66 feet wide to 84 feet. And a new street would appear on the maps, the 120-foot-wide, Railroad Avenue, located west of Front and Commercial streets.

Just as critical to enlarging the channels for business to flow was establishing a consistent grade for the new streets, which translated to raising them. Most of the Pioneer Square streets would be raised above the city’s datum point by an average of 19 feet per block, with the greatest change—32 feet higher—at Second and James.

Blue Balloon = 6.5 Red Balloon = 16-17.75 ft Green Balloon = 18-19.75 Ft Lt. Blue Balloon = 20-21.75 Ft. Yellow Balloon = 22-23.75 Purple Balloon = 32 Ft.

Most business owners supported the city council’s call for better streets, but they wanted to build immediately and the city could not match the pace. The issue was not widening, which was relatively simple since everyone was starting from scratch and a foundation could be built where necessary, but widening required major infrastructure change. The city had to erect brick or stone retaining walls, on the old streets, find material to fill in between the walls, transport the material to the site, fill in the street, and finally pave over, usually with wood, the surface of the new, higher street.

Not willing to wait, business owners started to build. Using stone and brick—the city had banned wood—they located their first floors at the level of the old streets. Since the city had yet to raise the streets, the sidewalks were also at this old level, which made it easy to enter the new business establishments.

As you can see from the map above (large files so may take a bit to load), the areaways extend throughout Pioneer Square. Below is the most up-to-date map of them I could find, where you can see that not all of them are in good shape. Intriguingly, at one point the City briefly considered using them for stormwater control. The idea was that water could flow into the open spaces. A study determined it was impractical because each original property owner was responsible for building up their facade and passage, which lead to a myriad of strategies and qualities.

Another way to trace the location of the areaways is to look for sidewalks with glass blocks. Flat on top and prismatic below, the glass let light into the subterranean canyons. Initially developed in the 1840s as deck lights for ships, vault lights were popular in cities, including New York, Chicago, Victoria, B.C., and Boston, from the late 1800s through the 1930s, when electric light prevailed. All of the prisms were originally clear and have since turned purple due to magnesium dioxide, which changes color under long term exposure to ultraviolet light. The reason you don’t see more in Seattle is that individual building owners are responsible for the vault lights in front of their building and it’s cheaper to cover them over than to upkeep them. There are still about 9,000 vault lights in the city.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.