David B. Williams's Blog, page 11

April 23, 2015

Seattle Stream Names – Pt. 1

Look at early General Land Office maps of Seattle from the 1850s and you will find dozens upon dozens of streams. Look at a modern map of Seattle and you will find very few streams, yet at least 50 named streams wind their way across the landscape. (I can only wonder at how many of the original streams never made it onto any map and how many are now covered by pavement.)

Over the past year or so, I tried to track down the names and locations of the streams, along with whatever I could locate about the origin of those names. My next few blog posts will detail the information that I found. If you do find errors, please let me know. Also let me know if I omitted any streams.

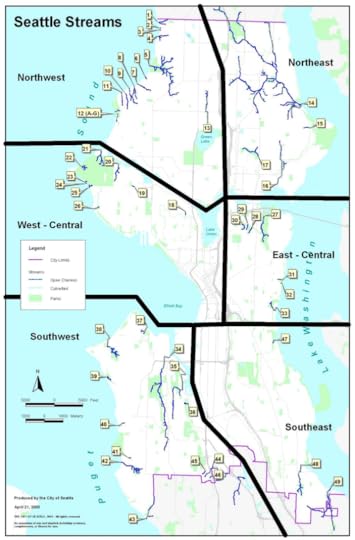

Unfortunately, there is no good map showing all of the streams. If anyone wants to produce one, I would be interested in helping out. The map that accompanies the names is from a US Fish and Wildlife Service Report. Distribution and Habitat Use of Fish in Seattle’s Streams Final Report, 2005 and 2006, by Roger A. Tabor, Daniel W. Lantz, and Scott T. Sanders. It was published in January 2010.

I will include the full map on the first post with close ups scattered throughout. The numbers on the names refer to numbers on the map. Creeks without numbers are not on the map but do or did exist. Click on the maps for a larger version.

Seattle Streams Full Map

Seattle Streams Full MapNorthwest Streams

4. Broadview – West side of north end of city – Apparently named for the neighborhood where it flows.

5. Piper’s – Flows through Carkeek Park – Named for early candy manufacturer Andrew William Piper, who lived on the land now preserved by the park. Piper owned the orchard in the park. Creek shown on 1909 USGS Topo Map of Seattle. (Enjoying Seattle Parks, by Brandt Morgan)

Mohlendorph – Tributary of Piper’s Creek – Named in honor of Ted Mohlendorph, who died in 1991. He was a passionate advocate for Seattle streams and worked at helping to preserve spawning runs at Piper’s Creek. (Seattle Times, Obituary, August 19, 1991)

5. Venema – Tributary of Piper’s Creek – Harry G. Venema and his family moved into the area in 1919. Born in Michigan, he had arrived in Seattle in 1908 and worked at Peoples National Bank and Seattle-First National Bank. Sons Jerry and Walt saw what was reportedly the last spawning salmon in Piper’s Creek in 1927. (Seattle Times, August 14, 2004)

13. Licton Springs – Historically flowed into Green Lake – Licton Springs is the only neighborhood with a native name that gives a clue to what the area may have looked like prior to the arrival of pioneers. The name is a corruption of the Lushootseed word liq’ted (LEEK-tuhd), which means “red” or “paint.” It refers to the iron oxides that still precipitate from springs bubbling out of the ground.

Northeast Streams

Lyon – Shown on 1897 USGS Topo Map Seattle Sheet – Not technically in Seattle. I included it because it is shown on this early map. A June 4, 1911, article in the Seattle Times described it as the “best trout stream in Seattle.” May also show up as Lyons Creek.

14. Matthews – Tributary of Thornton Creek – John G. Matthews arrived in Seattle in 1910. He was born in Kentucky, where he was a bank president and coal mine owner. In Seattle, he practiced law and invested in timber and coal. In 1951, the city purchased the land that became the park named for the family. (Valarie Bunn’s web site, wedgwoodinseattlehistory.com)

14. Littles – Tributary of Thornton Creek – The Little family settled near the modern Paramount Park in the early 1900s. They ran a sawmill and mined the peat in the ravine. Some early Park plans refer to a Jones Creek, which may have been a tributary of Littles. (Thornton Creek Watershed Characterization Report and Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department)

14. Willow – Tributary of Thornton Creek – Named by Martha Nishitani for a willow tree growing along the creek. (Correspondence with Valarie Bunn.)

14. Victory – Named for the Victory Heights neighborhood, which was named in 1920 for what we now call Lake City Way. The road was called Victory Way, from a little after WW I to about 1930. (Victory Heights Blog and Shoreline Historical Museum)

14. Mock – Tributary of Thornton Creek – The Mock family owned property on NE 97th Street, east of 35th Ave. NE. According to an interview with one of the daughters by local historian Valarie Bunn, one of her brothers worked for a weed-spraying company and used to come home and discharge the rest of his chemicals into the ravine where the creek flows. (Correspondence with Valarie Bunn.)

14. Little Brook – Tributary of Thornton Creek – Unknown origin but seems likely to have something to do with size but could be a family name.

14. Kramer – Tributary of Thornton Creek, entering South Branch, at 30th Ave. NE and NE 107th St. – Unknown origin.

14. Thornton – Creek with largest drainage of any in Seattle – John Thornton purchased the headwaters of what would become his eponymous creek in October 1, 1885. Four years later, the name Thornton Creek appeared on an 1889 land claims map, which makes it the earliest creek name to appear on a map. Born in Indiana, Thornton arrived in Steilacoom in 1850 and lived in the Dungeness/Port Townsend region. He never lived at, and may never have seen, his property in Seattle. South branch formerly known as Maple Leaf Creek. (Valarie Bunn’s web site, wedgwoodinseattlehistory.com)

Fisher – Thornton creek was also known by this name early in the 20th century. Unknown who Fisher was or whether it refers to an activity. Also could be Fischer, which seems more likely.

Evergreen – Tributary of Thornton Creek – Now known as Meridian, because community petitioned to change it.

Sacagawea – Tributary of Thornton Creek, entering South Branch, just west of Lake City Way

Hamlin – Tributary of Thornton Creek – The Hamlin family owned quite a bit of property in what is now Shoreline, though they did not homestead the land that became Hamlin Park. At some point, Seattle Trust and Savings acquired that property and donated it to the city. It is unknown when the name became associated with the creek; Vicki Stiles at the Shoreline Historical Society proposes that it was named when Hamlin was platting the land, at least as early as 1907. (Correspondence with Vicki Stiles, Shoreline Historical Society.)

15. Inverness – Flows off east side of View Ridge, overlooking Magnuson Park – Real estate man Jay Roberts gave the name Inverness Drive to the neighborhood he started to develop in 1954. The name was meant to convey the idea of the castle-like estates Roberts planned to build. (Valarie Bunn’s web site, )

16. Yesler – Flows into Union Bay near Center for Urban Horticulture – In the late 1880s, Henry Yesler moved his sawmill operations here to prosper from the great trees surrounding the north side of the lake; all of the forests closer to downtown had already been logged. The lumber was put on rail cars and taken back to Seattle via a train spur. Yesler arrived in Seattle in 1852.

17. Ravenna – Historic main drainage of Green Lake. – W. W. Beck bought the land that would become Ravenna Park in 1887. He named it to honor the Italian coastal city “that was famous for its pine trees, where poets, warriors, and statesmen once strolled in a state of euphoria similar to his own.” Name appears in October 1906 in City of Seattle Comptroller File 30782 for a petition for a foot bridge across the creek. (Seattle Parks Department web site on Ravenna Park)

Northwest and Northeast Streams

Northwest and Northeast Streams

April 8, 2015

Seattle Map 13 – Sandblasted in concrete

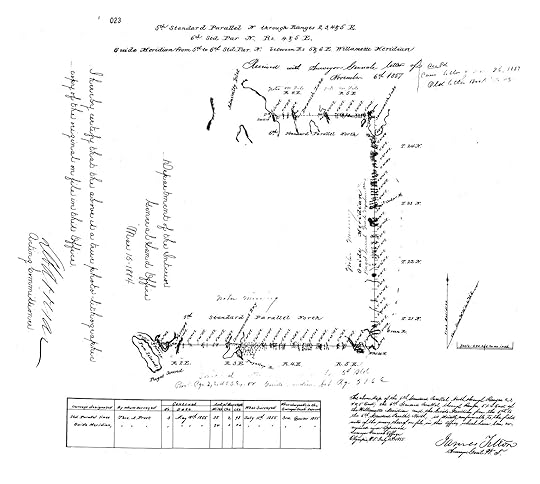

Although sandblasted into concrete, the version of this map that interests me has a Brigadoon-like nature, or at least it is not always visible. The map shows what is known as the Puget Sound Guide Meridian and is the first map to include Seattle in the great General Land Office (GLO) survey of the United States, or the system of townships that delineated public land into parcels that people could acquire. It is also called the rectangular, or rectilinear, survey system.

The survey had been established on May 20, 1785, when the United States Congress passed the Land Ordinance of 1785, which would create townships that measured six miles square. Each township was organized around a baseline of meridian lines that ran north south and standard parallels that ran east west.

The survey had been established on May 20, 1785, when the United States Congress passed the Land Ordinance of 1785, which would create townships that measured six miles square. Each township was organized around a baseline of meridian lines that ran north south and standard parallels that ran east west.

GLO survey work in Washington Territory began in 1855, two years after the territory had been separated from Oregon. Surveyor Thomas A. Frost was hired to survey three baselines critical for all future surveys of the territory: the Fifth and Sixth Standard Parallels and the Puget Sound Meridian.

All survey work in the state is actually based on the Willamette Meridian, which was established in near Portland, Oregon. You can go to see the spot at the Willamette Stone. Unfortunately, the Willamette Meridian runs through Puget Sound, making it bit challenging to use in this region, which resulted in the establishment of a Puget Sound Guide Meridian. The best detail on this story is Denny DeMeyer’s article, available here as a PDF.

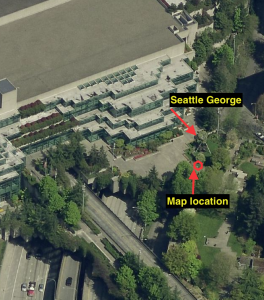

But back to sandblasted map. You can find it in Seattle, or at least try to, near the Convention Center. It’s behind the main Convention Center building in Freeway Park, below the Seattle George Monument by Buster Simpson. Created in 1998, Simpson’s art piece consists of a giant profile made of metal blades, part of which shows George Washington and part Chief Sealth. Just to the south and slightly west of the monument, Simpson sandblasted the map into the concrete, at the southeast corner of plaza. The map is just to the right, or east, of a red kiosk.

As you can perhaps see from the photos, the map is very faint, and on many days is barely visible at all, but it is almost the complete map, including the signature of James Tilton, the surveyor general for Washington Territory. Good luck.

Good Map

Good Map Same spot, no map!

Same spot, no map!

April 1, 2015

Page Proofs – Too High and Too Steep

Golly ned, the page proofs for Too High and Too Steep arrived yesterday. Very very cool. It looks like a book. Here’s a sneak preview. Written with a big old smile. Thanks to the UW Press for such a wonderful layout and design!

March 25, 2015

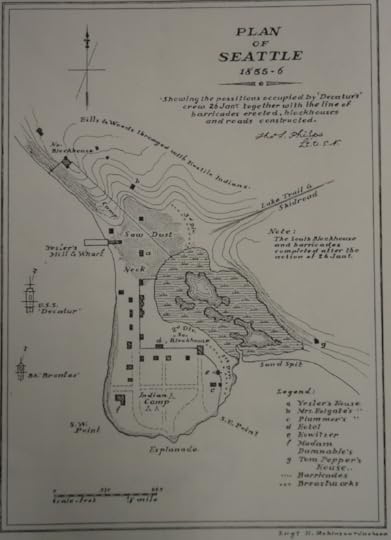

Seattle Map 12 – Phelps 1856

Perhaps the most famous early map of Seattle is the one drawn by Lt. Thomas Phelps. It depicts the young town in January 1856 and is the first to show the town and not just the landscape around it. Despite its fame, the maps has a convoluted history. To learn more, please follow this link to an essay that I wrote about the map for HistoryLink.org.

Many, many editions of the map have been produced. This is one of the more unusual. It is owned by the University of Washington Special Collections. I have no idea where it was printed or who the engravers were. If anyone does, please let me know.

Note several unusual aspects.

Addition of “hostile” to Hills & Woods thronged with …

Addition of “skidroad” to Lake Trail & Skidroad

Labels Thomas Phelps as a Lieutenant instead of Commander

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

March 16, 2015

PNW Nature Scavenger Hunt Post

Recently, Kelly Brenner asked me to participate in the PNW Nature Blogger Scavenger Hunt. The goal will be to answer a nature question on each of a variety of PNW nature blogs, just one question per blog. The hunt has been scheduled to begin on Monday at 8 a.m. and will run through Friday, 3-20-15.

Recently, Kelly Brenner asked me to participate in the PNW Nature Blogger Scavenger Hunt. The goal will be to answer a nature question on each of a variety of PNW nature blogs, just one question per blog. The hunt has been scheduled to begin on Monday at 8 a.m. and will run through Friday, 3-20-15.

Here is my addition to the fun. It is fairly long.

I like to think that I am knowledgeable about Seattle’s early history. I generally do well on those local history quizzes that newspapers publish when there is a slow news week and one of my earliest memories is of interviewing a descendent of a pioneer family for a story I wrote in third grade.

Despite having a head full of cocktail party-worthy facts about Seattle, I have been wrong for many years in the image I held of what Seattle looked like when the first settlers arrived. My botanical ignorance centered on big trees; I thought that a nearly unbroken forest of Douglas fir covered the hilly terrain from the shores of Puget Sound up to the Cascades. I pictured a forest “whose dark verdurous hue diffused a solitary gloom – favorable to meditations,” as naturalist Archibald Menzies wrote in 1792. It was an image fashioned partially by the women of the Denny party, Seattle’s founding families, who wept when they first arrived at Alki Point and discovered a dripping forest of giant trees.

When I began to investigate Seattle’s past I discovered my lack of knowledge. As I looked through old scientific journals and early survey reports, read modern ecological studies of the region, and talked to botanists, historians, and ecologists, I discovered far more complexity than I expected, particularly in regard to bogs, or what has been called a “history book with a flexible cover.” (May Theilgaard Watts, Reading the Landscape: An Adventure in Ecology, 1957)

Bog formation requires three factors, one of which relates to our damp climate and the other two to our glacial history. A surplus of water is the first need, a requirement met by our maritime-influenced high precipitation and mild temperatures. Second and third are infertility and poor drainage. As many local gardeners know, when the glaciers retreated 14,000 years ago, they deposited low nutrient soils but they also left behind shallow depressions, where water could stagnate. Bogs are generally restricted to the north, with the majority of North American ones in Canada and Alaska, and the majority of Washington state ones in the Puget lowlands. Although Seattle meets these conditions rather well, bogs were never common within city limits.

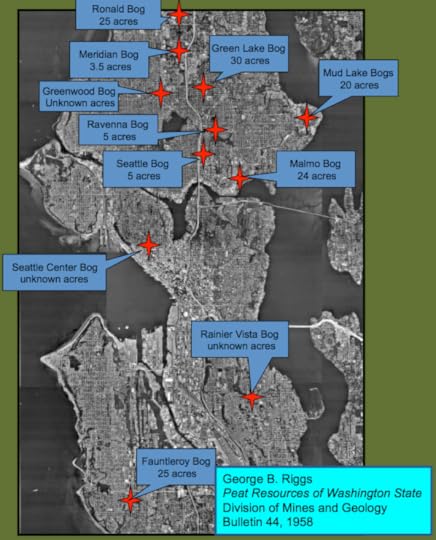

In searching through the scientific literature, I located descriptions of only a handful of in-city bogs, all of which no longer exist. As so often happens with wetlands, they were paved over for more useful purposes. For example, two have been covered by shopping centers, a 24-acre peat area under University Village and a cranberry bog now paved over by Northgate Mall. Others are known to have existed but simply passed too quickly from bog to home for anyone to write about.

Bogs in Seattle

Ironically, some modern residents have discovered a boggy clue, in ways that they probably wish they did not have to. In the summer of 2002, people living near 87th and Greenwood, in north Seattle, noticed cracks appearing in their walls. They also watched as two sinkholes formed, foundations sunk, and sidewalks buckled. Coincidentally, a new Safeway was the third major building project at that intersection in the past two years. It was also the third major construction site to have to pump millions of gallons of water from the site and the third to discover peat beds under the property.

I have not been able to determine when Seattle’s bogs disappeared but a landmark 1958 report on peat resources in Washington does not list a single bog within the city. The report, however, does mention clues that residents who lived in Seattle in the first half of the 1900s could have found. If they had visited a local garden store, like Malmo Nurseries, they could have purchased bags of peat moss, which had been mined from the former bogs. In peat mining, sphagnum moss is dug by hand, set out to dry, and then shredded and packaged. Some locals, in particular Japanese farmers, also made use of bogs, by draining them, and planting them with lettuce, cabbage, and other truck garden vegetables. Now, even these clues are gone with paving having replaced peat, Canadian sphagnum having replaced local sphagnum, and agribusiness having replaced small farms.

But we are in luck, one true bog remains, just outside city limits. It is a small lake just north of SeaTac Airport. To reach the water, known as Tub or Bug Lake, I parked on Des Moines Memorial Drive, walked east down a narrow path through blackberries, scrambled though a hole cut in a chain link fence, and continued to a narrow ditch, spanned by a circumspect looking 2 by 10. Such moats are a typical feature of bogs. Vegetation growing along the moat included hardhack (Spiraea douglasii) and western hemlock, which are stunted and may be as old as 300 years, even though they are only four inches in diameter.

Tub Lake

The plank was surprisingly sturdy, as opposed to the “land” on the other side, which felt like walking on trampoline. I was not actually standing on terra firma but on a thick accumulation of muck, brown, spongy matter, technically defined as sphagnum moss decomposed past recognition. As I walked atop the muck, water squeezed out from under my feet and accumulated in low spots in the path. After 25 yards or so, I moved out of the muck onto moss peat, also brown and spongy, but less decomposed than muck. I was now standing on a floating mat of sphagnum and peat and could make the nearby western hemlocks sway by jumping up and down and sending a wave through the mat. It only took about ten more minutes of jumping and swaying, jumping and swaying, for the novelty to fade.

The high acidity and permanent water made this environment no place for Seattle’s usual botanical suspects. Instead, I found bog laurel and Labrador tea, classic bog plants. In spring, the laurels produce spectacular pink blossoms. Labrador tea has smaller white flowers and both have dark green leaves that curl under at the edge. Searching under the shrubby tea and laurel, I also located ground hugging cranberries, which along with one of Washington state’s few carnivorous plants, sundews, only grow in bogs. I was past the sundew season but I know of others who have found them at this bog.

In another twenty feet, I was at Tub Lake. I didn’t dare jump up and down at this point, as I feared my floating mat would break off. Sedges, rushes, and cattails grew at the water’s edge and pond lilies floated in the water. If I had enough time, on the order of hundreds of years, I could stand at this point and watch as the sphagnum mat grew out into the water and the lake became a forested meadow, growing on top of the peat moss. Certainly a better fate then becoming a shopping mall.

I originally wrote most of this for my book, The Seattle Street-Smart Naturalist: Field Notes from the City. I have not been back to Tub Lake in over a decade so cannot tell you if it is still accessible. If you do go, please be careful and respect any signs you see.

March 5, 2015

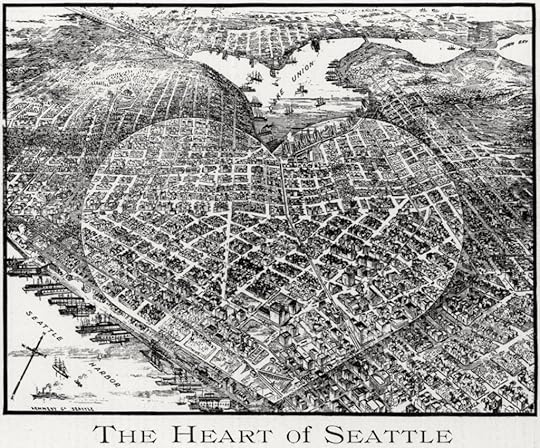

Seattle Map 11 – Heart of Seattle

My wife tells me it’s never too late for Valentines Day, so here goes. I recently came across this nifty map of Seattle, which originally appeared in the Seattle Star newspaper on July 5, 1907. Accompanying it was an article about the northward movement of the city’s commercial district. The map “will give the reader some idea of what sooner or later will be the heart of Seattle. As soon as the Denny Hill will have been lowered to grade great blocks will be erected on the site and that of itself will draw the city to it as well as beyond it.”

The map is curious for several reasons. I suspect that part of the oddities are due to the artist’s hope for what would happen, as well as some good guesses as to the direction the city was headed.

The map is curious for several reasons. I suspect that part of the oddities are due to the artist’s hope for what would happen, as well as some good guesses as to the direction the city was headed.

1. Government Canal – In the upper left part of the map, outside of the heart, the artist has included the “Government Canal.” (Sorry it’s hard to read but if you click on the image, you can get a larger version.) Work on what we now call the Lake Washington Ship Canal would not begin until 1911, with an official opening in 1917. In 1907, the existence of the canal was still uncertain. He/she has also drawn in a canal connecting Union Bay and Lake Union, though this 1907 canal is slightly south of the one that was actually built.

2. Dexter Avenue extends south of Denny Way – This extension of Dexter had been talked about for several years, including the possibility of building it as a viaduct, but unlike the canal, it never came to fruition.

3. Third Avenue and Stewart Street – On the northeast corner of the intersection, there is what appears to be the Securities Building, or at least a building of similar size. The Securities didn’t go up until 1913.

4. Denny Hill – It’s hard to tell but it looks as if the artist has already populated Denny with office buildings instead of the houses that still stood on the hill. The first huge regrade of Denny (often called Denny Regrade One even though it was the fourth regrade) wouldn’t start until 1908 and wouldn’t be completed until 1910. Planning was taking place so the map is not completely an artistic fantasy.

5. Westlake Avenue – This must be the one of the first maps to show Westlake Avenue and its south extension across the city street grid. It was only completed in late 1905.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

March 1, 2015

February 27, 2015

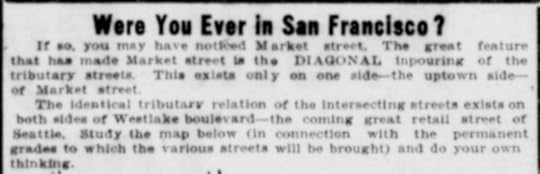

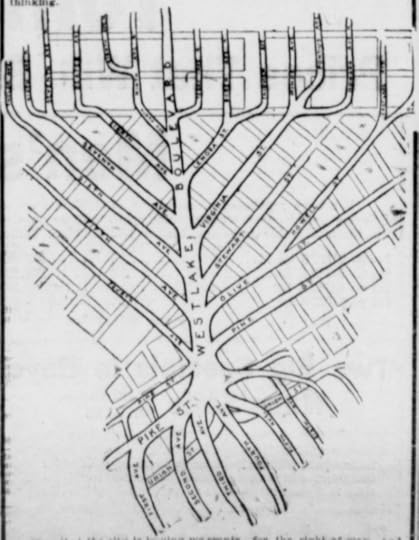

Seattle Map 10 – Westlake Avenue 1904

Many of us probably drive Westlake Avenue in Seattle without considering how odd it is. The street cuts diagonally across the normal, rectangular street grid. Few other streets do this. The diagonal originally started at Denny Way and ended at Fourth Avenue and Pike Street, which is why Westlake Mall is also not a rectangular space. Westlake north of Denny, or Rollin Avenue as it was originally known, had long extended north to Lake Union and continued on a trestle system around the lake to Fremont.

Planning for Westlake Boulevard started in 1901. Early articles noted that it would be expensive, primarily because of condemnation; run through several houses; and be a bureaucratic mess. Early plans called for dirt from the Second Avenue Regrade on Denny Hill to be used in areas that needed to be filled but it is not clear how much dirt was used. Work began in March 1905.

“When work starts on the south and all the buildings within the right-of-way from Pike Street north will be razed at the same time. There are several, which private persons have purchased, yet to be moved away, but many of the smaller structures will be town down and piled in a heap to be burned,” wrote an unnamed Seattle Times reporter on March 28, 1905. The contractor expected to have Westlake opened by the end of the year.

This 1904 map and accompanying text are from an advertisement in 1904. It gives a flavor of what the road’s proponents hoped would happen. In addition to increased property values they also hoped it would open up transportation routes to the north, which it did. For many years, at least one trolley traveled up Westlake.

Westlake Avenue 1904

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

February 24, 2015

Too High and Too Steep – Cover Background Information

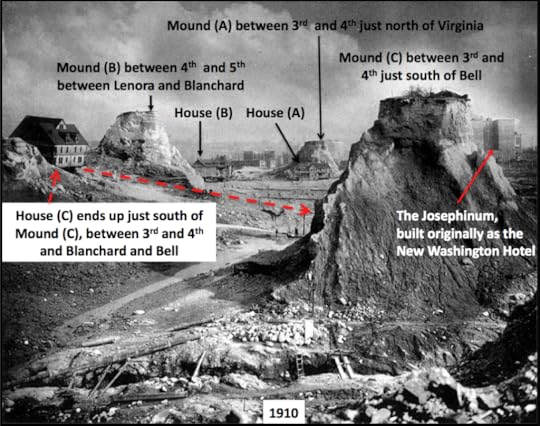

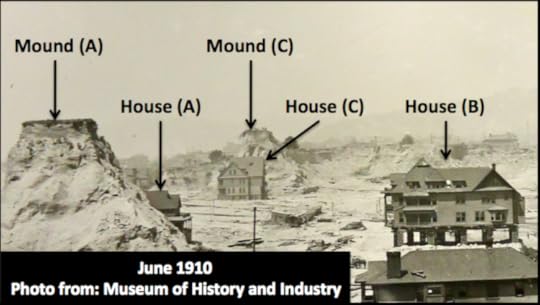

As a follow up to my post about my book cover, I want to provide some information about the houses in the photograph. Asahel Curtis took the most famous photograph of the regrades of Denny Hill in 1910, during what many call the first regrade of the hill but was actually the fourth regrade. The large Monument Valley-like towers are what are known as “spite mounds” or “spite humps,” which were supposedly owned by people who didn’t want to sell their property during the regrade. This is incorrect. I address this topic in the book.

Here’s information on the houses.

Asahel Curtis Denny Regrade

House (A)

2025 Fourth Avenue, property owned by Jasper Hoisington, who lived there with his wife, Nancy, as early 1901.

At the May 28 1909, Board of Public Works (public entity to whom land owners apply to move a building) meeting, J.C. Hoisington applies for permit to move house from 2025 Fourth Avenue to NW corner of 5th and Virginia and then to move it back following the regrade.

June 1919 – Musicians Association buys land.

1937 – Building leveled.

New building erected, General Tire and Battery, owned by Musicians Club, which continue to own the property to this day.

Regrade June 1910

House (B)

Property at 2018 Fourth Avenue, Mark Michelsen builds apartment building in 1903.

June 25, 1909 – Moving company Spear & McCoy applies to Board of Public Works to move house at 2018 Fourth Avenue two lots to the south.

Sometime between 1910 and 1912 – Ornamentation of house stripped, with new first floor inserted under the house. Now known as Michelsen Apartments

Leveled in 1956.

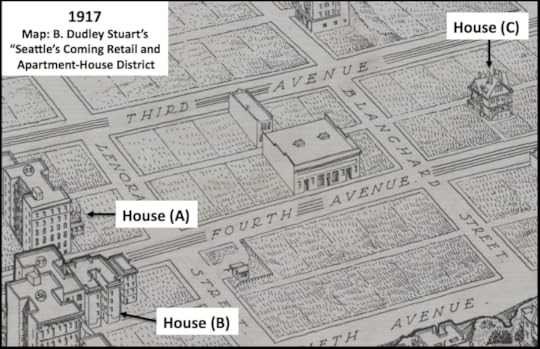

1917 Post-Regrade

House (C)

Originally at 2134 Fifth Avenue, SE corner of Fifth Avenue and Blanchard Street.

Owned by Roger S. Greene, who apparently purchased property in 1890-91 and built a house on it in 1892.

February 3, 1907 – Edward W. Comyns, working for Archibald and Cox buys SE corner of Fifth Avenue and Blanchard Street for $35,000.

February 8, 1910 – Gustave Havers (I don’t know what the relationship was between Havers and Comyns and why Havers was able to move this house) gets permit from Board of Public Works to move house at 2134-6 Fifth Avenue to 2215 Fourth Avenue.

1914 – Property listed as Bell forth Apartments, which eventually becomes Lee Apartments at 2217 ½ 4th, owned by S & R Realty.

The Josephinum still stands. It is now low income housing and his owned by the .

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

I will be giving a talk about the book and topographic change in Seattle for the MOHAI’s 4th Annual Denny Lecture on March 24.

February 10, 2015

Too High and Too Steep — The Cover

Golly ned, I am excited to reveal the cover for my next book. Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography will be published by the University of Washington Press in September 2015. Right now the book is moving through production. About two weeks ago, I turned in the copy-edited manuscript, which provided me the opportunity to address lots of details. Next time I see it, the book will be page proofs, which will be the first time I will see it as it will look as a book. Yay!