David B. Williams's Blog, page 8

January 21, 2016

Very cool cairn photo

I was recently contacted by Todd Ellis, a photographer based in southern Utah, who sent me this unusual, and I think subtly striking photo of a cairn from his neck of the words.

Photo by Todd Ellis

Photo by Todd Ellis

January 14, 2016

Putting Bertha in Perspective

So she’s not moving again. A few days ago Bertha’s barge got tippy, then on Tuesday, the ground near her started to give way and a massive sink hole appeared. Today, we have Governor Inslee putting out a cease and desist order, immediately stopping any further work by Bertha. The old gal cannot get a break.

I’d like to put this project in a bit of historical perspective. I am not apologizing for the slowdown but would like to point out that we have had a few projects that took more time.

Lake Washington Ship Canal and Locks – 63 years from conception to completion. Thomas Mercer was the first to propose a linkage between Lake Washington and Puget Sound via Lake Union, way back on July 4, 1854. The canal and locks officially opened on July 4, 1917. During the six decades it took to complete the project, there were federal reports, engineering reports, and naval reports. Attempts to dig the canal were made by lone individuals, speculators, Chinese work crews, and private corporations. And finally six different routes, including one through Beacon Hill, were proposed. Not until federal funding came through was the canal completed and it still took five years to complete the work.

Filling in the Duwamish River tideflats – At least 23 years. Seattle’s citizens had been dumping material in Elliott Bay since the upstart town’s earliest days but formal filling in of the tideflats didn’t start until July 29, 1895. In what was called the “greatest enterprise yet inaugurated in this city,” a dredge began to suck sediment out of one side of the tideflats and deposit it behind a barrier 2,000 feet away. By 1917, more than 90 percent of the tideflats had been filled, creating the monumentally unstable land of SODO and Harbor Island. Work had been stopped by lawsuits, the principal dredge company running out of money, and the occasional mechanical breakdown.

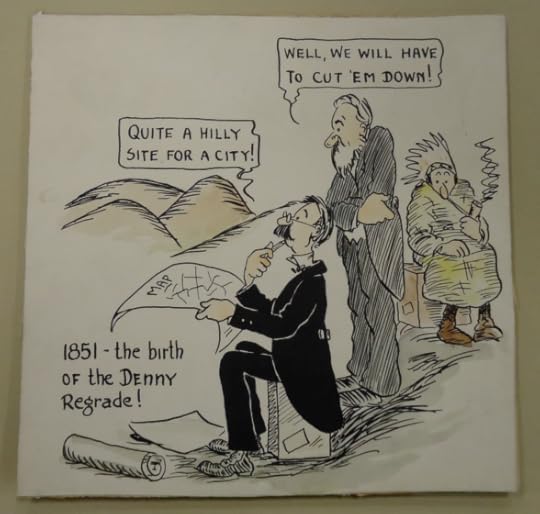

Denny Regrade – 33 years from first to last removal of sediment. It took five regrades to get rid of the great mound of Denny at the north end of downtown. The first was in 1897, followed by work in 1903, 1906, 1908-1911, and 1928-1930. There were workers who were electrocuted, who were attacked by children, who lost their arms, and who were crushed by landslides. A child taking a shortcut through the project died when dynamite being heated over an open flame exploded. Citizens sued the city and corporations. Corporations sued back. And, they even had problem with barges, which sank and ran into docks, shutting down the regrade. But on the plus side, they did find fossils from a mammoth, and they did complete the project.

So next time Bertha experiences a few delays, remember, she has a long way to go to break any record for most enduring Seattle project.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

December 17, 2015

Who’s Watching You?

I did a little walk around downtown Seattle yesterday. Here’s a few of the faces I saw. The first three were carved in Tenino Sandstone. The rest are terra cotta.

Grotesque 1

Grotesque 1 Grotesque 2

Grotesque 2 Grotesque 3

Grotesque 3 Grotesques 4

Grotesques 4 A Huddle of Walruses

A Huddle of Walruses A Horse, Of Course

A Horse, Of Course Nobility on High

Nobility on High

December 1, 2015

Last House Standing – In Memoriam

An obituary appeared in the Seattle Times today that I suspect few will notice, but the man who died marks the end of an era. His name was Curt Brownfield. I know of him because he lived in the last house left standing on a mound during the Denny regrades. It stood on a small rise at 307 Sixth Avenue North, at what is the present location of the Seattle City Light Broad Street Substation.

Brownfield House – Photo from Puget Sound Archives

Brownfield House – Photo from Puget Sound ArchivesThe Brownfield’s have deep roots in Seattle. In 1867, Curtis’s great-grandfather Christian and his wife homesteaded what would become the University District. Five years later, Christian and his son Curtis were hired to pull coal cars across the land connecting Lake Union and Lake Washington. Once the cars were across, they went onto the steamer Clara, which Curtis piloted down the lake to meet Seattle’s first railroad.

In 1906, Curtis’s son Frank, Curt’s father, moved to the house on Sixth Ave. Frank eventually became a marine engineer for Associated Oil Company. He lived there with his wife Mary and their six children. Curt was the fourth child, born in 1929, during the middle of the final regrade of Denny Hill. He lived at the house until 1942, twelve years after the regrade had been completed.

The regrades of Denny

The regrades of DennyDuring the research for my book, Too High and Too Steep, I was fortunate to speak to Curt about his experience growing up in the house. His first line to me in reference to the regrade was “that was a dumb idea.” (He also told me “Yeah we owned the U-District.”)

1936 Aerial photo of Denny regrade. By this time a few houses had been built near the Brownfields.

1936 Aerial photo of Denny regrade. By this time a few houses had been built near the Brownfields.“My parents were not very cooperative. They didn’t see why they should just pay anything extra,” said Curt. “They just wanted to live there. They weren’t going to benefit from the regrade.” So they decided not to go along with the city’s plans, which worked out well for Curt and his friends. There were no other houses around and the area became a sort of dumping ground that the youngsters would scavenge for fun items such as artillery and an Enfield rifle.

Seattle Times October 21, 1942

Seattle Times October 21, 1942To get up to the house, which was about 20 feet above the surrounding terrain, they had a wide ramp cut into the hill. It led to a flight of stairs up to the level ground of the house. In front, they could climb a steep metal staircase, which Curt’s father said came from a ship they were scrapping out. They usually used the back entrance as it was closer to the trolley tracks. To get coal up to the house, the coal man had to carry it up, Santa Claus-style, in a big bag.

Curt Brownfield’s notes to a photograph that appeared in the Seattle Times in September 1964. There is no information about when the photo was taken. (The pencil comment next to the house says “My diapers on line.”)

Curt Brownfield’s notes to a photograph that appeared in the Seattle Times in September 1964. There is no information about when the photo was taken. (The pencil comment next to the house says “My diapers on line.”)“People all around us were sold on the idea that once this area was flat, the property was going to become very valuable and developers were going to come in,” said Curt. “It was the wrong presumption. It never happened. The depression took over and business went downhill. Most people all lost everything. We didn’t lose everything because we didn’t go along with the regrades. It wasn’t a bad decision. It was a good decision not to have our house moved.”

By the early 1940s, Curt’s older brother had made enough money to buy a new house for his parents and the family moved to the top of Queen Anne hill. “My brother and sister were a bit embarrassed by the house,” said Curt.

A ship worker then moved into the house. He didn’t stay long though as on August 11, 1945, real estate operator James L. Napier, who had purchased the property, filed a permit for destroying the house. Later, the city built the power substation that still stands on the property.

Denny Hill was finally gone and now too is Curt Brownfield. My condolences to his family and thanks to his son for facilitating my interview. It was an honor to talk to Curt.

(Some of this text comes from Too High and Too Steep.)

November 13, 2015

A Floating Church in Seattle

I suspect that few people who walk up Jackson Street in Seattle’s international district realize they are walking past a floating church. Technically, it’s no longer a church nor is it truly floating but it is suspended above the street. The building is located on the northwest corner of South Jackson Street and Maynard Avenue South.

Here’s a shot of the modern building.

Former Japanese Baptist Church, Seattle

Former Japanese Baptist Church, SeattleThe former church is the top half of the building. Built around 1893, it sat on this corner until 1907, when the city began the Jackson Street Regrade. Often overlooked, it was the city’s largest, at least from the number of altered blocks. The project regraded 56 blocks and led to the excavation and subsequent embankment of 6.4 million cubic yards of material.

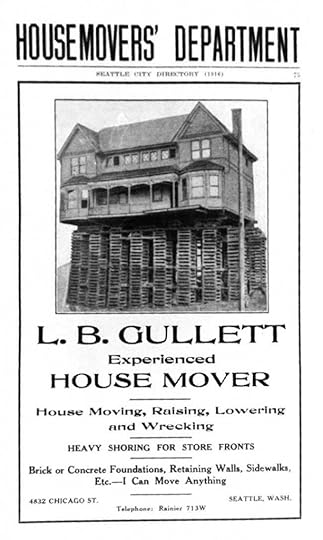

At Jackson and Maynard, the regrade lowered the street by 20 to 25 feet. Apparently the church owners did not want to destroy their building so they decided to save it and hired Lemuel B. Gullett, a local house mover, to move it.

Japanese Church, February 1910, photo from Washington State Historical Society

Japanese Church, February 1910, photo from Washington State Historical SocietyAfter the church was shored up on pallets, a new one-story brick structure, or foundation, was built on the site. Gullett then lowered the church on to its new foundation. In later years, the church became the Havana Hotel before undergoing renovation in 1984 and morphing into its present incarnation.

October 18, 2015

How to lower a lake – Seattle 1916

The other day my mom asked me a very basic question and one that I had never considered. How exactly did they lower Lake Washington during construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks? Completed in 1916 and officially opened in 1917, this was one of the great engineering feats of Seattle history.

Map of canals and locks, from Wikipedia

Map of canals and locks, from WikipediaIn order to keep the canal system (it consisted of two canals, or cuts, one at Montlake and one at Fremont) at the same water level, Lake Washington (LW) had to lowered down to the level of Lake Union (LU). (See map above to see how Salmon Bay connected via the Fremont canal to LU and LU connected to LW via the Montlake canal.) This necessitated about a nine foot lowering, as LW was 29 feet above sea level and LU at 20 feet. The LW number is not exactly accurate because the lake level fluctuated by as much as eight feet during the year; it was highest in winter. In addition, Salmon Bay, which historically had been a tidal inlet—filling at high tide and mostly draining out low tide—had to be raised up to the level of LU.

In regard to my mom’s question, I had long known that it “took” three months to lower LW but didn’t know the details on how they did it. Here’s a timeline of how they lowered the lake and raised the bay.

July 12, 1916 – Locks closed in order to flood Salmon Bay and raise it to the level of Fremont canal and Lake Union. “Within thirty days the greatest fresh water harbor on the Pacific seaboard will be open to ocean-going ships entering Puget Sound,” reported the Seattle Times. This was a typical response to the opening of a fresh water port in Salmon Bay.

Sluice gates in Lake Union, which controlled the water going into Fremont canal and eventually into Salmon Bay. Image courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Sluice gates in Lake Union, which controlled the water going into Fremont canal and eventually into Salmon Bay. Image courtesy Army Corps of EngineersJuly 30, 1916 – Steamer F.G. Reeve first boat to pass through the locks, which opened the long desired passage from Salmon Bay through the Fremont canal to Lake Union, now all at the same water level. Reeve used the smaller of the two locks.

Steamer F. G. Reeve. From Puget Sound Marine Historical Society

Steamer F. G. Reeve. From Puget Sound Marine Historical SocietyAugust 3, 1916 – Snag steamer Swinomish, under the command of Capt. F. A. Siegal, was the first boat to pass through the larger lock, “amid handclapping, cheers and the blowing of whistles,” wrote Thomas Francis Hunt in the Seattle Times. More than 2,500 people attended the opening. Next boat through was the Orcas. Both vessels did a quick spin in Salmon Bay before returning back to the locks.

August 25, 1916 – At 2 p.m., laborers used shovels to cut an opening into the cofferdam (temporary dam built to keep water out of the way) on the east side of Portage Bay. The plan was for the water to flow out of Lake Union and fill the Montlake canal. At the east end of the canal, or the very west side of Union Bay, were sluice gates, which would control the water flowing out of Lake Washington, still nine feet higher than Lake Union. An unknown skiff piloted by an anonymous man and two bare-headed boys was the first to run the canal.

Location of cofferdam, from Seattle P-I, August 26, 1916

Location of cofferdam, from Seattle P-I, August 26, 1916 Cofferdam in Portage Bay, Image courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Cofferdam in Portage Bay, Image courtesy Army Corps of Engineers“In exactly fifty six minutes the cut (Montlake canal) was filled to the level of Lake Union, and before the hour was up the current had ended and the eddies had ceased to foam. Logs torn from the cofferdam by the charging waters and hundreds of timbers and boards which covered the bottom of the cut floated to the surface…When the men with their shovels had broken the narrow neck of land, they sprang aside just in time to escape the inflow of water…In ten minutes the crowds on the cofferdam fled to escape being plunged into a raging torrent on the sides of the bank, which caved in in huge sections,” reported the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Breaching the Cofferdam, photographer is looking west from south side of Montlake canal up to Lake Union, Image courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Breaching the Cofferdam, photographer is looking west from south side of Montlake canal up to Lake Union, Image courtesy Army Corps of EngineersAugust 28, 1916 – Sluice gates in Lake Washington opened to allow water level in the lake to drop. Level was to be reduced about one and half feet in the first week with it dropping four feet by the end of September. Lowering Lake Washington down to the level of Lake Union did not occur until October.

Sluice gates in Union Bay, Image courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Sluice gates in Union Bay, Image courtesy Army Corps of EngineersBy late October 1916 – Lake Washington and Lake Union and Salmon Bay are at the same level and boats can travel from Puget Sound to Lake Washington.

July 4, 1917 – Official opening of the locks and ship canal.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

October 15, 2015

Seattle Technology Pt. 2 – The Self Dumping Barge

In my first technology post, I looked at the pile driver. I would now like to turn to an even less-heralded but rather fabulous piece of equipment, the self-dumping, reversible barge. They were critical to the final, 1928-1930, regrade of Denny Hill. Designed by naval architect William C. Nickum, the barges were used to tow dirt from the regrade out into Elliott Bay. Each cost $15,000 and was built by the Marine Construction Company. They were named the C.C. Croft and N.L. Johnson, after tugboat captains.

The barges were the same top and bottom with an open deck and two watertight chambers, or tanks, that extended the length of the barge between the decks. Each barge could carry about 400 cubic yards of dirt. To fill a barge, a tug nudged the barge under a chute built on a dock over Elliott Bay.

Filling barge Elliott Bay – May 1930

Filling barge Elliott Bay – May 1930The tug then towed the loaded barge into the bay, where a crew member pulled a rope that opened a valve in one of the chambers. Within three minutes, water filled the tank, and the out-of-balance barge flipped over, dumping its load. No longer weighted down by the dirt, the barge rose high enough to drain the internal tank, which took about eight minutes. The tug returned the barge back to shore, ready for its next load.

Getting towed out into Elliott Bay

Getting towed out into Elliott Bay Lopsided barge dumping its load into Elliott Bay May 1930

Lopsided barge dumping its load into Elliott Bay May 1930The barges, or the barge workers, did not always perform as planned. In September 1929, one barge smashed its mate causing it to sink. Three weeks later, after both barges were repaired, workmen left the seacocks open on one, which caused it to flip and hit its tug, which promptly sank. And finally a week later, the remaining barge flipped while at dock, damaging the dock and scow, both of which were put out of service, forcing the entire regrade project to shut down for several days. Tug drivers also had the problem of the barges disappearing in foggy weather, which caused delays. Still the self-dumping, reversible barge was an amazing piece of early Seattle technology.

Oops, should have been a bit more careful

Oops, should have been a bit more carefulAll images are from Seattle Municipal Archives.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

October 13, 2015

Denny Hill Humor

During my research on Denny Hill, I was delighted to find several cartoons about the hill. The first two were in the Seattle Times. The third one, I found in a folder with no information on its original source. Any information that anyone has would be appreciated.

August 17, 1954

August 17, 1954 November 22, 1962

November 22, 1962October 8, 2015

KUOW Interview

Today, I was interviewed by Ross Reynolds on The Record on KUOW radio. Here’s a link to the story.

September 11, 2015

Seattle Moves A Mountain – The Video

With the publication of my new book, there has been some well deserved attention to a video about the regrading of Denny Hill, made by the engineering department. Most of the web sites that include the video only show a few minutes of it. Below is the video in all of its 18-minute glory. It is quite wonderful, particularly the footage of the barges dumping the dirt into Elliott Bay.