David B. Williams's Blog, page 12

February 6, 2015

Filling the Flats

On July 29, 1895, thousands of Seattleites came out for what one paper crowned “the greatest enterprise yet inaugurated in this city.” They stood on a barge, watched from docks, and looked on from boats. (Fortunately, wrote one reporter, that nasty “old Sol” was hidden behind the clouds and no one would get too hot.) All were in the protean landscape of the Duwamish River’s tideflats, which for half of the day was underwater and for the other half was an expanse of mud. They had come to see an unusual boat.

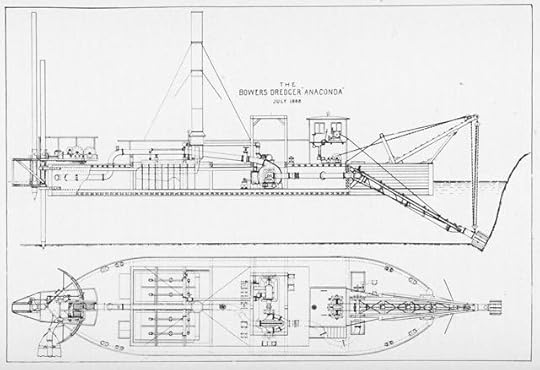

Anaconda Drawing

The Anaconda was 110 feet long and 32 feet wide with a spewing smoke stack and strange stern, which was attached to a long pole anchored into the tidal mud. The bow was also odd with a hoist that held a movable cutting head. The two part structure consisted of a seven-blade spinning cutter inside a 13-blade rotating cutter. Extending out of the hollow cutter was a suction pipe connected to a huge centrifugal pump. Built to suck up muck, the Anaconda could discharge 10,000 cubic yards of material every 24 hours.

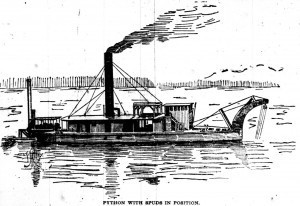

Eugene Semple, who had organized the event, owned the Anaconda. His plan was to use it and a sister dredger, the Python, to pump sediment from one part of the tideflats to another, in the process making new land for the city of Seattle. The main source of sediment would could from the Anaconda and Python excavating what are now the East and West Waterways on either side of Harbor Island. That sediment and material from the Jackson Street and Dearborn Street regrades, as well as from Semple’s failed attempt at a South Canal, would eventually lead to making around 2200 acres of new land.

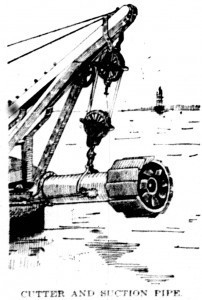

Close up of the Cutter Head

On that great day, Semple stood in the upper deck of the Anaconda’s engine room with his daughter Zoe. A reporter noted that Miss Semple made “a very pretty picture as she stood clad in a pure white costume…with a waist made of white dimity … and [a] skirt of white ducking.” (If any reader can educate me on what this means, I would appreciate it.) At 11:29 A.M., Miss Semple stepped up onto a wooden block, reached toward a small lever with her hand, and pushed it.

The Anaconda began to shudder as cogs turned and set in motion the blades of the cutting tool sunk into the mud 25 feet below the surface of Elliott Bay. Mud and water began shooting through a stationary pipe suspended above the tideflats. The 2,700-foot-long pipe curved northeast on triangle-shaped trestles to an area that is now just west of Safeco Field. At the time it was adjacent to the southern most wharves and piers in Seattle, where most of the crowd watched the event.

The pipe expelled the mud onto tideflats recently protected by a brush bulkhead. The structure consisted of two or more pile rows ten feet apart with six feet between piles. At the base directly on tidal mud was a mattress of young firs laid between the rows and built to one foot above low tide. Resting atop the mattress were 24-foot-long bundles of brushes, called fascines. Sand had also been pumped over the fascines to strengthen the support wall; the excess water escaped through the branches. With every three feet rise in elevation, a horizontal tree would be laid perpendicular to the bulkhead with its bare trunk over the fascine and its branched end extending into the area destined for fill. Additional strength came from anchoring the mattress and fascine to the tree trunks. More fascines and more tie-backs would be added until the fill reached two feet above high tide line.

The Python

By June 1897, the Anaconda and Python had excavated three thousand feet of the East Waterway to a depth of thirty-five feet below low water, which created 75 acres of made land. Seven years later, after various legal and financial setbacks, the total had risen to more than 333 acres. By 1917, about 92 percent of the tideflats had been filled.

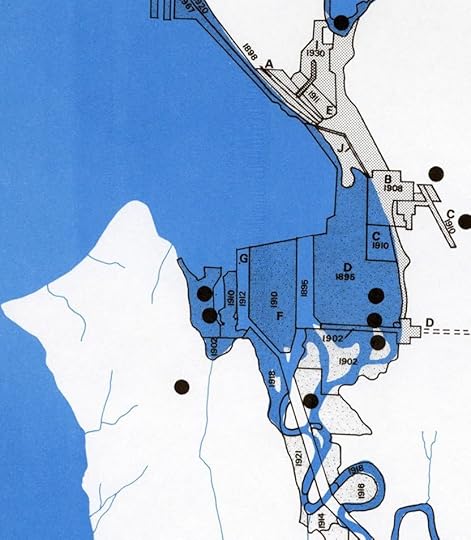

Tideflats Filling Dates, from: Determinants of City Form, City of Seattle, 1971

The last area of filling was west of Harbor Island, along the edge of West Seattle. It had remained somewhat wild through the 1940s, with a stream cutting across a sandy lowland but after World War II, industries, including a plant for creosoting wood pilings, a ship building facility, and later a banana warehouse, began to make the area more suitable for their needs.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

January 28, 2015

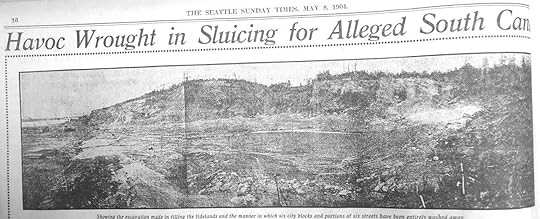

South Canal Seattle Photo

Of all the crazy schemes that didn’t come to fruition in Seattle, the South Canal through Beacon Hill is one of my favorites. Unfortunately, I know of only one photograph of it and it’s not very good, but I have decided to look at it anyway. (Just wish I knew how to make provide one of those magnifying things so it can be looked at more closely.) As I noted in a previous post, little of the South Canal was built. Here is that story.

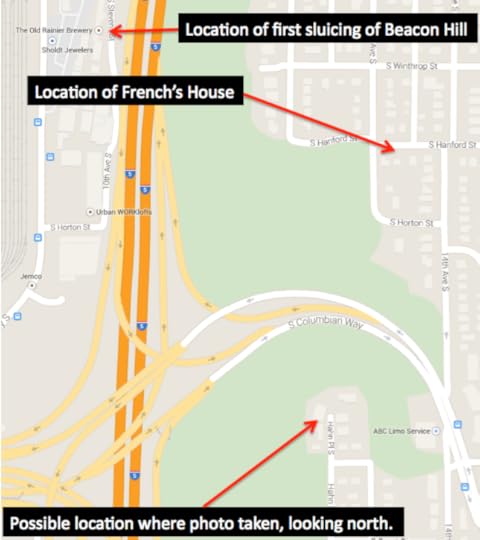

Semple’s Folly on Beacon Hill – View looks north toward S. Hanford St. Note hydraulic cannon on right side and tideflasts to the far left. S. Columbia Way cuts through middle of this scene in modern times.

The hill-cutting phase of the project had begun in February 1901, when Eugene Semple acquired rights to surplus water from the city’s new water source, the Cedar River. Built as a response to the lack of water to put out the Great Fire of 1889, the new system brought water from the Cedar River to reservoirs atop the city’s hills. Semple’s plan was to take advantage of the elevated reservoir on Beacon Hill by tapping into it via wood stave pipes. Water from Beacon Hill would drop nearly 300 feet down to the base of the hill. As the water plunged down slope, it would enter narrower and narrower high pressure steel pipes, which would increase the water pressure to the point that the water shot out with enough force to dislodge soil, rocks, and boulders.

On November 14, Semple’s crews began their attack on the western edge of Beacon Hill, directly east of the Bayview Brewery at 10th Ave S and Hanford Street. Everyday the crews blasted the hill with 14 million gallons of water, which created about 2,000 cubic yards of fill that flowed in flumes out into the Duwamish River’s tideflats. The first area filled was just north of the brewery, where the Washington Iron Works and Frye-Bruhn Meat Packing Company would be able to replace their old pile-supported buildings with new structures built on the new land.

By late 1904, the hydraulic giant had blasted away enough of Beacon Hill to create 52 acres of solid land along the hill’s western edge. But not everyone was happy. Philip and Maria French filed a petition with the city council seeking an award of $6,000 for damages to their home. The couple lived atop Beacon Hill, at 14th Avenue South and Hanford Street. Originally built more than 700 feet from the edge of the hill, the house and surrounding property were now just 30 feet north of a 100-foot-high sheer cliff created by Semple’s hydraulic cannon. Amazingly, the French’s lost their case.

Map of area covered by photograph.

Wielding a bit of hyperbole, the Seattle Times reported that “without authority and unknown to the public,” Semple’s crews had washed away seven streets of Beacon Hill, creating the “great hole” adjacent to the French’s property. The resulting damage suits against the city, added the Times, were piling “up so high that the corporation counsel is unable to see over them.” In contrast, real estate agents didn’t understand the Times’ concerns. Henry Dearborn noted that that “it is certainly good business ethics” to sluice down less valuable lands, such as Beacon Hill, in order to create more valuable land below.

With all of the bad publicity, Semple’s plan was doomed. By the end of 1904, the city council had voted to stop Semple’s use of Cedar River water. Eventually weeds started to grow in the chasm that was to be the South Canal and the project became another example of Seattle’s failed attempts at creating a new transportation corridor.

The chasm still survives. Have you ever wondered why the Columbia Way off ramps from I-90 go up to Beacon Hill where they do? It’s because the I-5 engineers took advantage of Semple’s folly, which provided a nice access point up to Beacon Hill.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

January 15, 2015

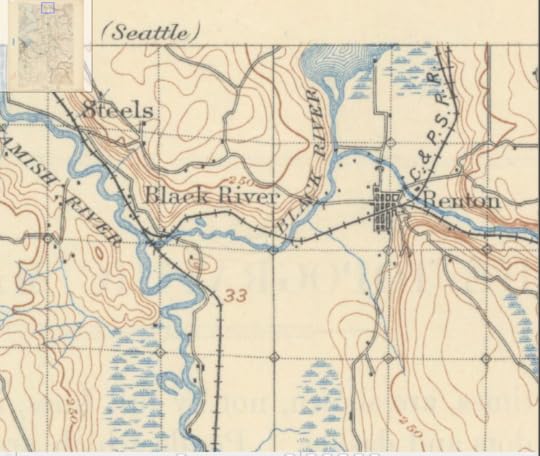

Seattle Map 9 – Black River

The Black River is Seattle’s most infamous river, or more accurately, lost river. The river was only about three miles long but was critical to the early history of the city. It was Lake Washington’s lone outlet and hence lone access point for boats traveling from the salt water of Elliott Bay to the fresh water of the lake, a route replaced in 1916 by the opening of the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the Lake Washington Ship Canal. (The canal officially opened on July 4, 1917, but the canal and locks had been completed in 1916.)

As you can see from the accompanying map, the 1909 USGS Topographic map of the Tacoma quadrangle, the Black flowed out of the lake near Renton, and was almost immediately met by the Cedar River, coming west out of the Cascade Mountains. The Black then wound around low hills, under the Columbia and Puget Sound RR, and met the Green River, where now became the Duwamish with the addition of the Black.  Historically, the Green River flowed into the White River in Auburn, and the two continued as the White to the confluence with the Black. Floods in 1906, however, changed the course of the White, which now drained, and still drains, into the Puyallup River. The Green kept its course and now became the outflow for the Black, until the disappearance of the Black in 1916, which is why the Green changes name for no apparent reason and becomes the Duwamish.

Historically, the Green River flowed into the White River in Auburn, and the two continued as the White to the confluence with the Black. Floods in 1906, however, changed the course of the White, which now drained, and still drains, into the Puyallup River. The Green kept its course and now became the outflow for the Black, until the disappearance of the Black in 1916, which is why the Green changes name for no apparent reason and becomes the Duwamish.

The Black’s name came from sediment washed out of the Cedar’s old river terraces. The White was significantly clearer. Although not as sediment rich, the White had powerful spring floods, which would push up the Black River, such that it flowed back into Lake Washington. This is the origin of the name for the Black in Chinook jargon, Mox La Push, or “two mouths.”

King County’s first sawmill outside of Seattle was at the confluence of the Black and Cedar rivers. Started in 1854 by Henry Tobin, Joseph Fanjoy, and O.M. Eaton, it had two circular saws. In order to operate the mill, the trio built a six-foot high dam. Unfortunately for the men, the mill did not last long; the Black was too windy for transport. It was not too twisted though for vessels.

Soon after the discovery of coal near what is modern day Issaquah, a variety of people were “engaged in wordy discussions of the quickest and best way to render the Squak coal mines available,” noted The Seattle Gazette in February 1864. In floated William Perkins, who built a boat, floated and paddled to the mines, and returned with a full load. The 140-mile-long trip via the Duwamish and Black rivers and across Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish and back took him 20 days. Trips up and down the riparian highway eventually became easier as river travelers dredged sand bars and cleared out stumps and overhanging vegetation.

But everything changed in 1916, when Lake Washington was connected to Lake Union, which lowered the level of the larger lake by nine feet. This was enough to drop the lake below its historic outlet and the Black River slowly died, with remnants persisting until at least 1969. A photograph shows a narrow swath of shrubs, weeds, and cottonwoods that curved east between North Third and Second Streets toward the intersection of SW Sunset Boulevard and Rainier Avenue South. That last vestige of the Black now lies under the parking lot of a huge Safeway.

The other remnant of the river still exist. At its confluence with the Duwamish is the Black River Riparian Forest. Not the most beautiful of spots but following years of restoration, visitors have reported over 50 species including salmon, coyotes, salamanders, and bald eagles. The area also supports the largest heron rookery in the region.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

January 7, 2015

Lyons and Lions in Seattle

One of the most unusual building stones in Seattle is the Lyons Sandstone. I know of only one building built with it. That building is now known as the Interurban but began life as the Seattle National Bank. The new name came about sometime after 1902 when the Tacoma Interurban railway terminated in front of the building. Running from Tacoma via Green Valley and with an off shoot to Renton, the Tacoma Interurban ran from 1902 to 1928.

Lion of Lyons

English-native John Parkinson designed the building in 1890-1892. He later moved to Los Angeles where he is much better known, especially for the Los Angeles Coliseum and City Hall. In Seattle, he also designed the Butler Block, sadly most of which was removed; the upper brick clad stories have now been replaced with a rather banal garage. At the least the handsome granite base remains.

The classic Romanesque Revival building is a delightful ediface. At the base is the local Chuckanut Sandstone, a gray sandstone. Sitting atop it is the Lyons Sandstone, quarried at the Kenmuir Quarry in Manitou Springs and shipped by rail to Seattle. I have not been able to determine why Parkinson chose the Lyons rock, though it clearly contrasts well with the Chuckanut and complements the brick that makes up the remaining part of the building. The Lyons was deposited as sand dunes during the Permian Period around 280 million years ago. Outcrops of the rock, which often appear as massive hogbacks, occur along the Front Range of Colorado, including such famous areas as Red Rocks Amphitheater and Garden of the Gods. Minute quantities of oxidized hematite (that is rusted) give the Lyons its red color.

Lyons Sandstone was the most commonly used sandstone building stone quarried in Colorado. Quarries opened in the 1870s and continued in Manitou until the 1910s, and still takes place in Lyons, where descendents own the quarries opened by their relatives in 1873.

Welcome In…pfffth.

What makes the Interurban particularly charming are the elaborate carvings. The most obvious is the lion overlooking the entrance at the corner of Occidental and Yesler. More intriguing figures are found in two additional locations. To the east on Yesler is another entrance, where you can find grotesques on the columns. (There is some debate about the origin of the term grotesque, but many trace it to paintings in Roman grottoes.) These curious faces were a commonly used architectural feature, often adding a sense to a whimsy to stately structures. Another grotesque peaks out from carved foliage on the southwestern side of the building. It’s about 20 feet above ground level.

What you looking at?

These are not the only grotesques in Seattle. I know of one building that has 78 carved in its sandstone. Do you know it? There is also another curious feature on the Interurban. Do you know it?

December 18, 2014

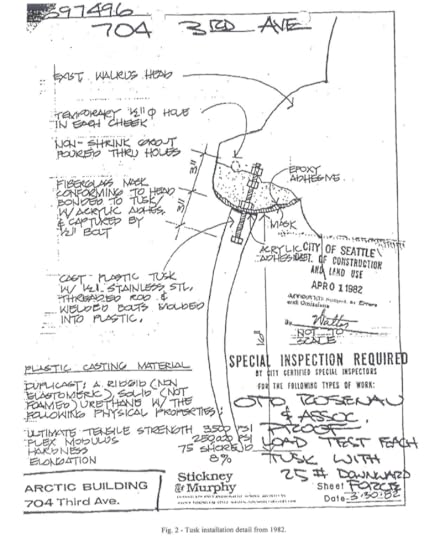

Walrus Heads in Seattle

They are arguably the most famous heads in Seattle but unlike many others they say nothing. They only stare out wide-eyed in all of their tusked glory. They are, of course, the 27 terra cotta walrus heads on the Arctic Building at Third Avenue and Cherry Street. Designed by Augustus Warren Guild and opened in 1917, the building was originally the home of the Arctic Club, a Seattle-based social club.

Walrus at Night

The walruses have a storied history. Originally made by the Denny-Renton Clay & Coal Company, the heads consisted of three parts, two tusks and a head, all made from terra cotta. The tusks were held in place by steel rods and a sulfur-based bonding agent. Some have claimed that the original tusks were ivory or marble but this is wrong. There is also a rumor that one of the tusks fell out during Seattle’s 1949 earthquake. I have not been able to find any evidence that this happened but all of the tusks were supposedly removed following the quake.

Finally, in 1982, the walruses got a little dental work with the installation of brand new tusks. They were made of molded urethane. Since they didn’t have the originals they had to create entirely new ones. One person involved in the project told me “We didn’t have any images so I went to the library to find photographs.” They were made by Architectural Reproductions, Inc., now Architectural Castings.

WJE Photo of Wounded Walrus

Embedded in each tusk was a threaded stainless steel rod, which extended about 3 inches beyond the tooth and was then inserted into the head into grout, or what I like to call snout grout. Within a year or two, cracks in the head appeared. They were repaired with epoxy and the repaired heads repainted.

More cracks appear in the 1990s. A study in 1996 by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. (WJE) determined that the snout grout was responsible for the cracking. Apparently moisture had entered the heads and reacted with gypsum, which had then expanded in the confined space, as if the walruses had really bad head colds. This led to the replacement of 13 heads. Because no one in the area could make new heads out of terra cotta, the new ones came from Boston Valley Terra Cotta, in Orchard Park, NY. The other 14 were repaired. All of them contain the tusks made in 1982.

WJE Drawing

Before leaving the heads behind I want to make a somewhat off subject foray. According to that great font of word wisdom, the OED, the walrus was previously known as the morse. In addition, the word walrus has a challenging etymology, which was worked out by none other then J.R.R. Tolkien. I think that’s sort of cool, though the OED doesn’t offer up any information on what seems to be could be the plural of walrus, or walrusi. After all we have cactus and cacti. Why can’t we have walrus and walrusi? I am waiting to hear from my more Latin-knowledgeable pals.

December 12, 2014

Bertha Hysteria

Another day, another problem with Bertha. This time it has to do with cracks and settling and groundwater and planning and fixing and … It’s amazing how many problems that Bertha has had. I want to focus in on the newest map released by WSDOT. Shaped perhaps ironically like another embattled landscape—Israel—the WSDOT shows the ground surface settling around the Bertha access pit.

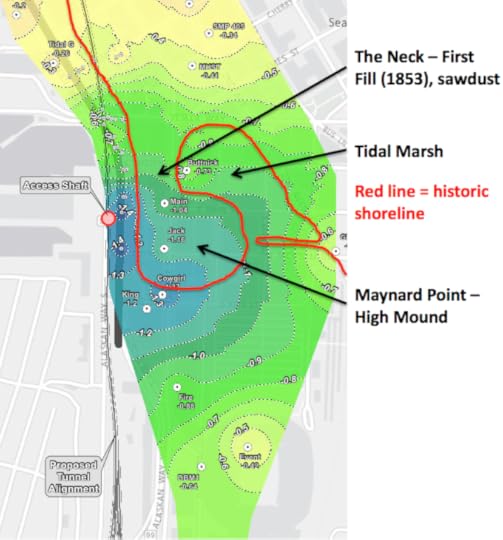

Below is a zoom in on the map, where I have added an outline of Seattle’s historic shoreline in red. You can clearly see that the areas of greatest settlement correspond to where the city was filled in around what is known as Maynard Point. (Also known as Denny’s Island, but this is a made up name that probably didn’t come into existence till the 1960s.) Maynard Point was a mound that rose perhaps 20 feet or so above sea level. It connected to the main part of Seattle by The Neck, a low spot that would periodically be covered by tides, converting the mound into an island. The Point has also been buried by fill.

Our sinking city

Ever since WSDOT released information last week about their groundwater problems, people have been in a tizzy about the ground settling. Pioneer Square has had groundwater and settling problems for decades. Why do you think the sidewalks tilt? They weren’t built that way. Why do think so many buildings have steel retaining rods sticking out of them? They do because the ground is settling. Why do buildings have sump pumps, which are needed more often in the winter during high tides? The Seawall doesn’t stop the tide; it’s not supposed to either. Why do parking lots undulate? Cores show that under the surface is a stew of crap, including coal, lumber, pilings, wood debris, sawdust, ceramics, sand, boulders, charcoal, ash, bricks, metal, glass, that continues to decay, compress, and settle.

Or walk along Western Avenue between Yesler and Columbia. It looks to be an engineer’s nightmare. The middle of the street is higher than the sides and the entire road surface undulates. The concrete curbs also look as if they had been poured by a drunkard, sometimes disappearing under the street and sometimes rising eight to ten inches above it. Near the southern end of the street is a low point that every time I have walked by is a pool of water.

In 1996, the Washington state Department of Transportation (WDSOT) drilled a core nearby as part of a seismic vulnerability study of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. In the first four feet of the core, the drillers found three inches of asphalt, three inches of railroad ballast, or gravel, 12 inches of concrete, and 18 inches of broken concrete, pieces of creosote timber debris and rounded gravel. The technical report then lists organic soil and “a void from 4.0 ft. to 8.0 ft” before hitting moist, loose soil again. Fourteen and a half feet down the core changes to pieces of creosote timber and a new feature, an aroma of rotten egg and sulphur. The remaining 8 ½ feet of core is described as contaminated organic soil. A final note adds “See samples at own risk.”

Ask any building owner or tenant in the area and I suspect they will be able to tell you additional stories of how their building is anything but immobile.

I am not writing this to defend WSDOT, (I am not a Bertha booster), but no one should be surprised by ground surface and subsurface issues in this area. It certainly looks like Bertha has contributed to the problem but it does not bear sole responsibility. These problems are the legacy of the landscape where we live and that we have altered continuously since first settlement. And there is no end in sight…to the alteration and to the settling.

December 10, 2014

Seattle Map 8 – Other ship canals

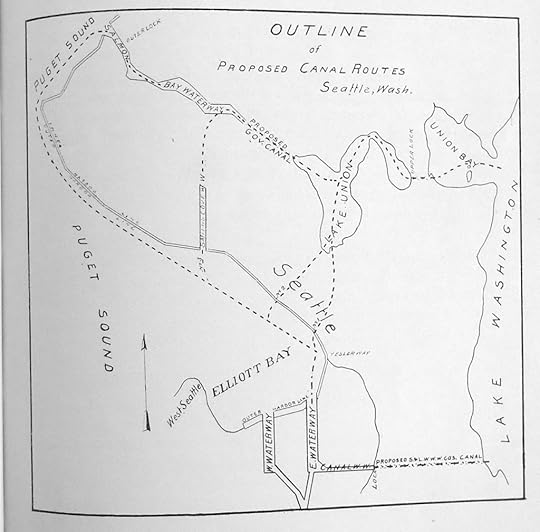

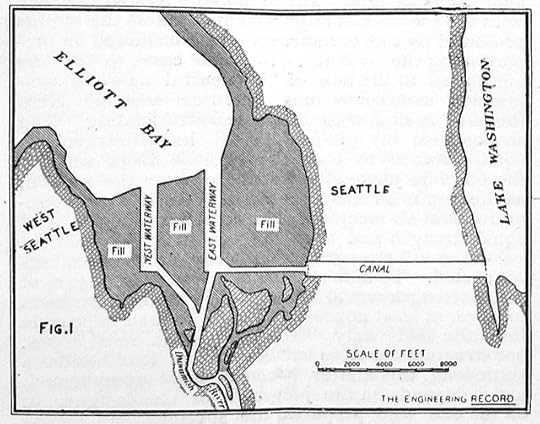

Following up my map showing the planned for but never executed South Ship Canal through Beacon Hill, I have a map that shows other potential ship canals. These are for the north end of the city. Map is from History and Advantages of the Canal and Harbor Improvement Project Now Being Executed by the Seattle and Lake Washington Waterway Company (1902).

All of these routes were put forward in an 1871 description by Brig. Gen. Barton Alexander titled “Ship-Canal in Washington Territory.” The United States government was interested in a canal to facilitate naval vessels docking in Lake Washington’s less damaging fresh water, instead of in the salt water of Puget Sound. For each total length is from foot of Yesler Way to deep water in Lake Washington.

1. Pike Street Route – South end of Lake Union up Westlake Avenue (which did not exist at the time) to Pike Street to Elliott Bay = 6.5 miles

2. Mercer Farm Route – Direct route to Lake Union at about Battery Street = 6.9 miles

3. Smith’s Cove (Interbay) Route – Total length = 10.5 miles

4. Salmon Bay to Lake Union = 16.9 miles

Despite having to make a 119-foot-deep cut for his favored routes (Mercer Farm and Pike Street), Alexander rejected a canal connecting Lake Union and Salmon Bay because it required too much dredging and would suffer from exposure to the “cannonade of an enemy in time of war.” In his conclusion, Alexander observed that the Puget Sound region offered one of only three places on the Pacific coast to build a secure port for the United States navy but the area possessed too few people and resources to justify further study.

Not until 1917 did a ship canal open. Of course, that is the modern one from Salmon Bay through Lake Union to Lake Washington.

North Ship Canal Routes

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

December 5, 2014

South Canal Beacon Hill

On July 29, 1895, six thousand people stood and listened as local dignitaries extolled the virtues of a canal that would connect Puget Sound and Lake Washington. Ex-Governor Eugene Semple, who was the principal project organizer and promoter, concluded his talk by telling the audience to come back in five years to witness the dedication of the canal locks. His 22-year-old daughter, Zoe, then climbed the steps of the massive dredge Anaconda, pushed a lever that started a hollow rotary cutter ripping into the tidelands, and began the linkage of salt and fresh water in Seattle.

Enthusiasm ran high for the canal. Over 4,000 people had packed into the Seattle armory only three months earlier to discuss the project. The crowd gave not only an endorsement but a pledge to raise $500,000. The goal was met by May 10 with nearly 2,500 people contributing between $1 and $20,000. The Seattle P-I called the canal “the greatest undertaking yet inaugurated in the city.”

No one, however, showed up five years later to celebrate. Powerful political foes had effectively turned public sentiment against Semple’s canal. Seattle’s citizens would have to wait until 1917 to celebrate the opening of a canal—and it wasn’t the ex-governor’s touted route, which would have cut from the mouth of the Duwamish River through Beacon Hill to Lake Washington.

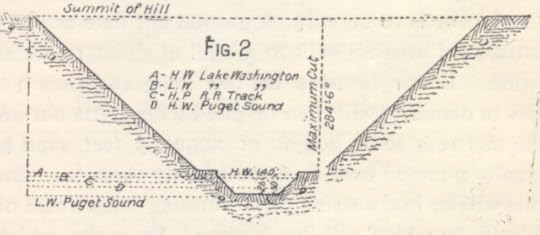

Cross Section of South Canal, Beacon Hill

South Canal Seattle

As you can see from the map (this is the only map, albeit not a terribly detailed one, that shows the canal) and cross section, Semple’s plan was audacious, and one might also say insane. To cut through Beacon Hill, the canal would have to be nearly 300 feet deep and at the base of a one-quarter-wide gorge. Although no canal was ever built, Semple’s company did wash away a big chunk of Beacon, which many Seattleites experience every day. It is the gap that takes South Columbian Way up the hill from I-5 and the Spokane Street bridge.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page..

December 3, 2014

Bertha – One year anniversary

One year ago today, an eight-inch-wide pipe went clunk, grind, and pfffth. Yes, it’s the anniversary of when Bertha, THE WORLD’S LARGEST TUNNEL BORING MACHINE, started to become the butt of jokes, world wide speculation, and persisent second guessing. After traveling for more than a 1,000 feet on her epic quest to drill a more than 9,000-foot long tunnel under Seattle, Bertha effectively came to non-grinding halt. The project is behind schedule, over cost, and even worse, a black eye in the fair face of Seattle’s ongoing quest to be a world class city.

The infamous pipe was 60 feet undergound and left over from a 2002 project to measure groundwater along the Alaskan Way Viaduct when Bertha attempted to gnaw her way through it. She wasn’t successful and instead pushed much of the pernsnickity pipe out of her way and kept digging for another three days. Bertha only stopped when she began to overheat. Her Twitter account of Dec 9 noted in an understatment: “Seeing some reports that I’m stuck. I’m working fine, but have encountered an obstruction.” Well, the reports were correct and she wasn’t actually fine.

WSDOT has longed claimed that the pipe was not the problem yet it seems rather peculiar that it took the tunnel gang one month to report the pipe to the public. As often happens, attemping to hide the truth gives a worse impression than simply being honest. It also seems curious and/or inept that they didn’t plan for the pipe, when they had documents showing where it was located. It makes sense that they could have done something about the pipe, like remove it.

Bertha has moved just a handful of feet since December 6, 2013. In the past year, we have learned that her main bearing seal was damaged. For some reason, contaminants had infiltrated the seal, making Bertha inoperable. Did the pipe harm the seals? Was it some unusual sediment? Was it something that won’t be discovered until they take Bertha completely apart and give engineers a chance to get their first complete look at the complete machine? At this point, we don’t know and one wonders if and when the lawyers will let us know.

We also don’t know when Bertha is going to be up and running again. The Seattle Tunnel Partners tells us that they are on schedule to start again in March 2015 but their track record does not necessarily lead one to believe that that will be the case. We’ll just have to wait and see, in what has turned into an epic story.

A few observations and questions.

Engineers and crews have spent the past several months getting ready to take Bertha apart. Are they going to be able to put it back together correctly? How many of us have done something similar and not been able to repair the mess we made. And will they assemble it better than they did the first time?

Did we get a lemon and did the contractor know it? As was pointed out last February, this wasn’t the first time Bertha had problems with her seals. They were also problematic in Japan, where she was built and where the problems were discovered during testing. Some have claimed that she wasn’t fixed right in the first place.

This raises a follow up question after Bertha hit the pipe and began to overheat, why exactly was there the concerted push to keep her moving. Is it coincidental that Hitachi Zosen, the company that built Bertha, owns her for the first 1,300 feet, with Seattle Tunnel Partners taking ownership past that distance? If she had only gone another 300 feet, STP would face greater responsibility. Was there outside pressure to keep her moving beyond the 1,300 foot mark?

What if it happens again, if a seal breaks or some other unexpected mechanical problem arises? As bad as the present situation is, it couldn’t have happened in much better of spot. Soon Bertha will be too deep to have a repair job on the order of the present one.

Many have observed that the STP doesn’t appear to know what is under Seattle. According to geologists I spoke with, STP had and has a very good picture of what was and is under Seattle. People have been digging up the city for decades and rarely do they find something that unexpected. (One might argue that the SLUT (South Lake Union Tusk) was unexpected but it really wasn’t. We know that mastodons, as well as giant sloths, lived and died here. They have been found before and will be again.) In a way, the tusk is similar to the oysters shells unearthed in October. It provides another detail to the story we mostly know, which is valuable, as it helps make the history of Seattle more fascinating and more accessible.

The archaeological work following Bertha’s stoppage has been one of the few positives. It has been done well but like Knute Berger, I wish that WSDOT archaeologists used the opportunity to do more than simply what is required. It would be great for them to see this as an opportunity to tap into resources they didn’t expect to see.

November 25, 2014

Seattle Map 7 – Bird’s Eye 1891

Augustus Koch arrived in Seattle in the summer of 1890. Like many his age, 49 years old, he had fought in the Civil War, where he had been draughtsman making maps. He had come to Seattle to do the same but it would not be a typical map. For the past two decades Koch had traveled the country producing fantastic aerial views of cities from Jacksonville, Florida, to Los Angeles. One newspaper reporter gushed that Koch’s maps depicted “every street, block, railroad track, switch and turn-table, every bridge, tree, and barn, in fact every object that would strike the eye of a man up a little ways in a balloon.”

Koch achieved the same exquisite detail in Seattle, except that his imaginary viewer would have been very high up in a balloon, looking down at Seattle from a perspective over what is now Pigeon Point in West Seattle. Measuring 32 by 50 inches and published as a limited edition lithograph in January 1891, the map took six months to complete. (I have not been able to track down what it cost, how many were printed, who sold it, and how many survive.) Koch’s map combines an engineer’s quest for details and an artist’s imagination to make those details come to life.

Plying the waters of Elliott Bay are more than a dozen schooners, colliers, barks, tugs, sternwheelers, and paddle wheelers, as well as another dozen double- and triple-masted ships and paddle wheelers. Koch has named three of the larger vessels, the steamships Willamette and Walla Walla, and the U.S. Man of War Charleston, each more than 300 feet long. Long used for transporting coal from Seattle, the Walla Walla had recently been fitted as a passenger ship running between San Francisco and Puget Sound. Also making the same run was the Willamette, which in 1890 carried more than 49,000 tons of coal to California.

Koch’s smaller vessels were part of the legendary Mosquito Fleet. Generally powered by steam and with flat bottoms, which allowed access to shallow ports and travel up river, the fleet ferried everything from eggs to mail to people to lumber. They were the short haul truckers of the day, keeping far flung communities throughout Puget Sound supplied with goods from the main port in Seattle.

What stands out most is the phenomenal presence of rail. Fifteen trains, the longest of which pulls 16 cars, travel on tracks to, through, and from Seattle. More waiting boxcars rest on the tracks and thirteen trolleys carry passengers across the city. The tracks of the trains so dominate the waterfront that you cannot reach any part of Elliott Bay from Beacon Hill to Smith Cove without crossing at least one and up to five tracks.

Supplementing the several miles of train trestles on the tidal flats is an extensive wharf system. They give the city’s south end an appearance of trying to become a new Venice, floating atop the water. These were working wharves with a ship building facility, several lumber mills with vast piles of logs, immense coal bunkers, railroad depots, boiler works, a hotel, a laundry, and a foundrys. More piers extend west over the tidal flats from the base of Beacon Hill, including one shingle mill with a vast pile of sawdust in front of it, reminiscent of sandy island in a tidal lagoon.

I have no reason to doubt the basic veracity of Koch’s drawings. In other parts of the country where Koch worked, modern researchers have compared his bird’s eye views with photographs and maps and found him to be remarkably accurate. I have though talked to a maritime historian who told me that all of those ships couldn’t have been in the harbor on the same day (they would needed too much space to turn around), but his portrait accurately reflects what a typical Seattleite would have seen in their growing city.

In the 18 months since the Great Fire of 1889 had burned downtown to the ground, everyone had rushed to rebuild, usually bigger and certainly more substantial with brick and stone instead of wood. The sounds of hammers, saws, chisels, sledges, and pile-drivers resounded with the Seattle Spirit. Ships arrived daily bringing in goods and supplies and taking out raw materials. Seattleites would have to wait two more years for direct transcontinental rail service, but trains arrived and departed daily from points south and east. It must have been an exciting time to live here.

Although the map represents Koch’s vision of Seattle, and not a true-to-life photographic picture, it does provide a remarkable snapshot of a city on the cusp of change from its pioneer roots to its status as the most important city in the state.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.