David B. Williams's Blog, page 14

October 10, 2014

Friday Photo: The world splits apart

Another photo from past travels. This is from one of my favorite spots on Earth, where I spanned what is normally a great gap with a single short walk. It is also the place that gave the world the words thing and booth.

Any thoughts of where?

Friday Photo 10-10

October 6, 2014

Seattle Map 3 = Manhole Covers

My guess is that most people walk right over my favorite maps in Seattle. There are at least 14 of them that I can find, though there were originally 19 in the city. Excuse the pun, but the maps are in the most pedestrian place possible, on manhole—though now the PC term is hatch cover (apparently no one cottoned on to peoplehole)—covers throughout downtown.

The idea for Seattle’s hatch cover art began in 1975 after Seattle Arts Commissioner Jacquetta Blanchett had traveled to Florence and seen the city’s hatch art. Working with Department of Community Development director, Paul Schell, Blanchett donated enough money to fund 13 covers, with six more paid for by other donors. Each cost $200 and weighed 230 pounds. The first one was put in place in April 1977, on the north edge of Occidental Park. It is still there.

Anne Knight designed the map. A map was natural because Seattle had such a “graphically interesting street pattern,” she said. Anne thought that the map covers would make an excellent teaching guide, as well as a guide to the city. If you look at covers (except one), you will see there is no compass. A City of Light employee had told Anne that one thing he didn’t want was a compass on the map. Otherwise, the crews would have to orient the cover correctly each time. So there is no compass, though there is a map, which one would hope wouldn’t be too challenging for the City of Light crews to orient. Apparently it is. Despite Anne including a small welded bead on the outer ring of each cover to facilitate easy alignment, nearly all of the covers are misaligned at present.

In addition, Anne included a raised, polished bead indicating the location of the cover within the city. They can still be seen on the maps.

The images are fairly large so might be a bit slow to load.

Anne told me that a police officer had heard about the project and called her to say he was concerned that pedestrians would be stopping in the middle of the street to look at the maps. She told him not to worry as she had only chosen spots on corners.

Each of the maps includes city landmarks, such as the post office, the Seattle Public Library, King Street Station, and Denny Park. You can figure out which one is which by looking at the key on the map’s outer edge. All of the landmarks still remain except for the Kingdome. “At the time it had just been built and I thought naively that it looked like it was a structure that would be there forever,” Anne said.

Curiously, the manhole cover on Second Avenue between Spring and Seneca has a unique, post 1975 landmark on it. That landmark is the Seattle Art Museum. In order to fit that landmark on the key, Harborview Hospital was dropped. The map is also the only one not on a corner. (Anne does not know the exact origin of that cover; a special one was made for the Seattle Art Museum but it was removed when the Hammering Man fell and damaged it.)

As you can see from the accompanying annotated map, not all of the original 19 covers exist. I could locate only 13, plus the later one added on Second Avenue. Neither Anne nor the City of Seattle Office of Arts and Cultural, which administers the city’s artwork and which supplied me a list of the original locations, knows the present location of all of the maps. One is now in Kobe. (This one had been moved to an alley and a City of Light employee had removed it and happened to have it in his truck when he attended a sister city meeting and suggested sending the cover to Kobe.) Several others have been moved and/or removed with their whereabouts unknown. One that was on the original list apparently was never in that location and there might be one at the Seattle Center, which was moved during reconstruction of the Monorail, but I haven’t found it.

These manhole maps are one of the delights of Seattle. So next time you are out walking around downtown, take a look down at your feet. You might be amazed at what you find.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

October 2, 2014

E. coli in Seattle…Almost

The recent scare of E. coli near Seattle got me thinking about the city’s drinking water. Seattle has some of the cleanest drinking water in the country, which always prompts me to be amazed when I see people buying five-gallon jugs of water. The reason it is so clean is because the city owns the entire watershed of its primary water source, the Cedar River. The only chemicals it adds to the water are chlorine and fluoride, with a little lime to adjust the Ph. Seattle Public Utilities also finishes the water with ozone and a UV treatment to kill giardia and cryptosporidium.

The Cedar has been the city’s primary source of drinking water since inadequate water pressure during Seattle’s Great Fire of 1889 led to an 1,875 to 51 vote, just 32 days after the fire, to approve a one-million-dollar-bond to form a publicly owned water system. After an additional 12 years of haggling, planning, and construction, water from the Cedar reached Seattle on January 10, 1901. Roughly 30% also comes from the South Fork Tolt River Watershed, 28 miles east of Seattle, which the city first tapped in 1964. (People north of the Ship Canal generally get Tolt water, although water gets mixed in the system, particularly at the Maple Leaf reservoir, so a tap could deliver pure Cedar, pure Tolt, or a mix of the two.)

Clean water has been a central concern since the earliest days of the city’s involvement at Cedar River. It has not always been easy. In 1906, the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound Railway proposed to run their train line through the watershed and along the Cedar River. An editorial in the June 21, 1906, Seattle Times stated that if the trains went through, “the people of this City will become impregnated with the microbes of typhoid fever, dysentery and every foul disease known to humankind.” The solution ended up being relatively simple, health inspectors got on board at Landsburg or Cedar Falls, and locked the doors to the restrooms between the two areas, thus ensuring that no ‘foul diseases’ made their way into the Cedar River and into the city’s drinking water. The city also had a requirement that city employees had to be vaccinated annually for typhoid.

More problematic were the towns, homesteaders, and logging camps that dotted the watershed. For example, the logging town of Barneston covered 80 acres. The largest town was Taylor, home base for the Denny Renton Clay & Coal Company, where a couple hundred people lived and made tile and brick. Nearby was Sherwood, as well as two Weyerhaeuser logging camps. The sewage of both towns drained directly into a creek that flowed into the Cedar River, according to another Seattle Times article. To alleviate these problems, a drainage ditch was eventually built at Taylor to prevent water from reaching the Cedar River. Many logging camps also had portable toilets, even in the 1920s and 1930s.

Despite the avowed concerns of City officials about clean water, which led to an ordinance in 1908 that restricted access to the watershed, a detailed study from 1912 noted that “in every camp or mill where men are employed, hogs are an important adjunct…and have a free range and access to the water.” Cattle and sheep were also common and unrestrained, particularly along Taylor Creek. Such conditions “would not be tolerated in a properly controlled watershed.” The report, however, concluded that “the water of Cedar River, Cedar Lake and some of the small tributaries is excellent.”

Adding to the problems in the watershed was the widespread logging. About 83 percent of the watershed was logged. Such denudation did not specifically alter water quality but did lead to much greater duration, high turbidity events. The loss of a healthy forest ecosystem led to increased soil erosion.

In spite of the recent E. coli scare, Seattle does have amazing water, and certainly better water now than early in its history. We are fortunate that all logging stopped in 1997, and that there has been active forest restoration and removal of old roads. The city also benefits from a Habitat Conservation Plan, adapted in April 2000 to protect the watershed’s endangered species. Primarily this means Chinook salmon but also an additional 82 species—from blue-gray taildropper slugs to peregrine falcon—must be monitored and protected, which will result in a healthier ecosystem and ultimately in cleaner water for everyone, be they plant, animal, or human.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

I also want to thank Ralph Naess of SPU for his help with this story.

September 30, 2014

Bandits and Henchmen

A group of bandits and henchmen invaded our yard today. Their appearance is an annual event, at least for the bandits, who tend to arrive in early autumn, hang out for 10-20 minutes and then leave. In contrast, I can see the henchmen year round. Of course, I am not writing about people, but about birds. The bandits are cedar waxwings, a gray brown bird with a sporty, almost mohawk crest. A black mask covers their eyes giving them their nefarious appearance. The henchmen are dark-eyed juncos, in particular the Oregon form with their conspicuous black hoods and handsome little pink bills.

Cedar waxwing - From Wikipedia

Junco - photo by Tom Grey, birdweb.org

As usually happens, the waxwings appeared suddenly, with a flurry of wings and high pitched whistles. They had come to dine on berries on our black hawthorns. Our hawthorn, the native Crataegus douglasii, is about 35 feet tall with 1-inch-long thorns. I always appreciate when the waxwings arrive because they tend to decimate the berries, which are abundant enough to make our path a mess.

Waxwings are fun birds to watch through binoculars as you get glimpses of the shimmering red wingtips and yellow tipped tail. They are active birds flitting from branch to branch, stopping periodically to swallow a berry, though I watched far too many birds drop the berries right back down on to our path. With at least a dozen birds flapping and winging around, it looked as if the tree was going to take flight.

One Mr. Forbush once described the birds this way. “Like some other plump and well-fed personages, the Cedar Waxwing is good-natured, happy, and tender-hearted, affectionate and blessed with good disposition. It is fond of good company.” He also reported on the birds surprising habit of passing a cherry along from bird to bird as they sit in a row. No one knows why.

Although I can see the juncos any day of the year in our yard, and regularly when out hiking, I still enjoy watching them bounce around. They were formerly known as common snowbirds, and are more common in winter, when they descend from the mountains and foothills. Like many small birds, they seem to be in constant motion, hopping about the ground in search of seeds, berries, and arthropods.

Now they are all gone. The yard is quiet. The hawthorn has fewer berries. I await the return of the bandits.

September 24, 2014

House on a Hill: Seattle Regrades

Over the past few days, several people have sent me a link to this wonderful set of Seattle then-and-now images by Clayton Kauzlaric. What he does that is unusual is to create a composite with an historic shot woven together with a Google street view. Images include the original shoreline, parades, and regrades. Perhaps the most iconic is this one of a house formerly at the corner of Sixth and Marion. The historic photo is from the regrade of Sixth Avenue, which occurred in 1914. As reference, it is about eight blocks south of the southern end of the Denny Regrades, which took place in 1903, 1906, 1907, 1908 to 1910, and 1928 to 1930.

Sixth and Marion Blend by Clayton Kauzlaric

Entrepreneur Joseph F. McNaught built this house around 1881. At the time, “the older men of Seattle shook their heads at this foolish whim,” wrote Margaret Pitcairn Strachan, in a story about the building in the March 4, 1945, Seattle Times, in part because the house sat on a “tremendous hill, along a cowpath.” McNaught’s home originally faced Sixth Street (later Sixth Avenue), with horse stalls and carriages to the south toward Columbia Street. In 1890, a regrade of Sixth left the house perched high above the street. When the house was lowered to the new street level it was turned ninety degrees, to face Marion.

McNaught House in all its glory - Seattle Times

Dr. P.B. M. Miller and his wife Eva eventually bought the McNaught home from speculator Bert Farrar and converted it into a rooming house, which they named the Ross-Shire. Their children owned the building, known variously as the Ross-Shire Apartment, Ross-Shire Hotel, and Hotel Ross Shire, when the main regrade of Sixth took place in 1914. In this image from January 1914, you can see an excavator at work on the hill holding up the Ross-Shire. On the corner of the building is a sign advertising the Ross-Shire Cafe.

Ross Shire Cafe, January 1914 - City of Seattle Municipal Archives

Eleven years after the regrade, Harvey M. Todd bought the house. He made significant changes to the original structure, adding apartments, sleeping rooms, and a “modern hot-water heating system,” as well as lowering the yard to allow light into basement apartments. According to Paul Dorpat, the building ended its life when I-5 was built. By this time, it was part of a complex known as the Marion Hotel.

Later in the life of 603 Marion, a bad preproduction from the Seattle Times

I have one final comment and I don’t mean it to be too critical of the wonderful images created by Clayton Kauzlaric but I am a bit compulsive about trying to get the facts straight. His image faces the wrong way. The McNaught house was on the southeast corner of Sixth and Marion and Kauzlaric’s image puts it on the northeast corner, or at least he has the image facing northeast. He may have done so for artistic reasons—the composite is framed beautifully—but to see a correct now-and-then shot, you can go to Paul Dorpat’s web site, which has some additional information about McNaught and the property.

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.

September 17, 2014

Singing Rocks: Geology Songs

Few scientific disciplines lend themselves more to song than geology. The science is exciting, touches our lives daily, helps us understand the world around us, and is filled with wonderful words that lend themselves to rhyme and verse. Consider that one of the most famous bands in history sports a geologic name – The Rolling Stones. We have songs about continental drift, erosion, volcanoes, earthquakes, and dinosaurs, though some think that geology songs don’t fare well. Here’s the dialogue from Prairie Home Companion, and its infamous private eye, Guy Noir.

SS: Mr. Noir— I’m Louise. You know Brad Paisley—

GK: Yes, of course.

SS: Top star in Nashville for years — and then he suddenly comes out with an 8-CD boxed set called Rocks–

GK: Rocks.

SS: And it’s all songs about geology. Tectonic plates. Volcanoes. Geysers. Shore erosion.

GK: Interesting.

SS: Not really. A half-million copies of those CDs are in landfill in New Jersey. And now— we have to relaunch Brad as the exciting performer that he used to be before he got fascinated by soil.

GK: And what’s my job?

SS: Keep him indoors.

And, later in the broadcast.

BP: This is a volcanic hot spot in Hawaii. It’s for a TV special I’m writing a soundtrack for. I just can’t explain how the sight of red hot lava bubbling up from the ground — I just find it moving— the earth reforming itself…..continents shifting……earthquakes……I want to learn more and more about geology— have you ever read John McPhee’s book, Rising From The Plains?

GK: Yes, I’ve been reading it for ten years every night just before I fall asleep.

BP: I just find the science of geology so exciting….so fulfilling— I don’t want to sing about love anymore. I want to sing about the earth.

TR (GORE): Brad, I’m Al Gore, and I want to congratulate you on your interest in geology and earth sciences. I admire your ambition to use country music as an educational tool and I myself have written a number of songs on this subject—

SS: Mr. Vice-President, I’m sorry, but we have a show to rehearse—

TR (SINGS): Let other people hang out in bars. I lie on the rocks and look up at the stars. (BRIDGE)

Oh, well not everyone sees the light but many do, so here’s a short list of web sites that focus on geology-themed songs. After all why do you think they call it Rock and Roll?

1. Focus on education – http://www.songsforteaching.com/geolo...

2. A long list of songs that touch on geology – http://academic.udayton.edu/heidimcgr...

3. A short fill-in-the-blank list of geologic songs – http://www.funtrivia.com/en/subtopics...

4. Teaching geology through a couple of songs – http://www.dinojim.com/Geology/GeoEdu...

5. The Exploratorium and Earthquake Songs – http://www.exploratorium.edu/faultlin...

Any other suggestions?

September 15, 2014

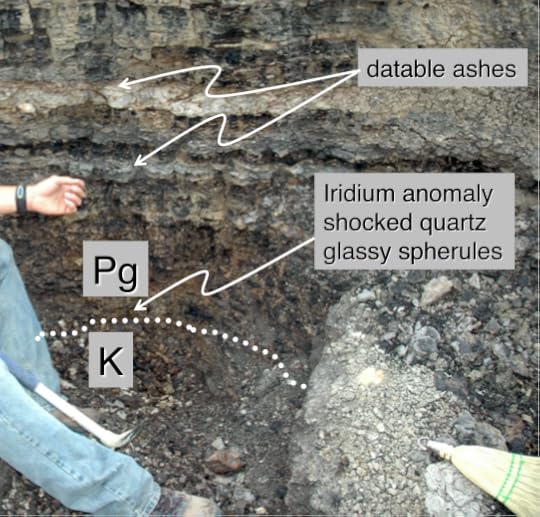

Friday Rocks: K/T Boundary

My Friday Rocks photo shows the K/T boundary, aka the Cretaceous/Tertiary Boundary. I took this photograph in August 2011, when I was out in the field with the Dig School, a wonderful education program co-founded by Burke Museum paleontologists Greg Wilson and Lauren DeBey. We were about 16 miles north of Jordan, Montana. The site is known to paleontologists as Lerbekmo Hill, after geologist Jack Lerbekmo. One of the highlights of the spot is that I could place my hand on the iridium anomaly layer, the famous bed of material that helped geologists understand what happened to the dinosaurs, and many others, at the end of the Cretaceous. In addition, about ten miles away is the location where Barnum Brown found the first specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex. It’s certainly one of the niftiest spots for any geogeek to visit.

Here is another view of the location showing the different layers.

K/T Boundary

September 12, 2014

Friday Rocks: Photo in the Field

I thought I’d try something different this week, at least different for me, and post a shot from the field. This spot illustrates one of the most famous moments of time in geology. What makes this location most compelling is that it is near where some of the world’s most famous extinct beasts were found. It’s just a hundred yards or so off of dirt road. Any guesses where the shot was taken and what it shows?

Where is it? What is it?

Where is it? What is it?

September 9, 2014

She Moves! Bertha in Seattle

After months of sitting idle, Seattle’s multi-million dollar tunnel boring machine, Bertha, finally inched forward. Last Thursday and Friday, she advanced by three feet, though advance might not be the proper word as she is moving to having her innards sundered, as part of her epic repair job. I won’t comment on that part of the story. What I would like to mention is what was found during the archaeological process of digging a hole to reach Bertha. This digging took place quite awhile ago, in March, but I have yet to see anything about it in the news and only recently learned of it.

The archaeologists found one of the most infamous landscapes of early Seattle—Ballast Island. As the name implies, the island was born out of merchant ships dumping their ballast after arrival in Seattle. At present, ships carry water as a stabilizing ballast. Historically, when ships arrived in port with no cargo, they needed to carry dense but inexpensive ballast, such as rocks or bricks, which would be dumped and replaced with cargo. This is what happened in Seattle, primarily dumped from the Stone and Burnett Wharf at the foot of Washington Street.

According to J. Willis Sayre’s This City of Ours, ballast rock from Valparaiso to Sydney to Boston to Liverpool eventually ended up in Seattle. Sayre, who was a theater critic and journalist, wrote several books about Seattle history. Each is quirky and provides first hand stories about early Seattle. His list of cities shows up repeatedly in books about Seattle. There is no reason to doubt Sayre’s observation of where the ballast originated but also no references to support it either. Many early articles in the Daily Intelligencer wondered why the city didn’t use the ballast for something useful, such as filling in wharves or macadamizing roads. The stone could be collected and broken up for the roads by “city prisoners…at a trifling expense,” noted one editorial.

Ballast Island soon grew large enough to show up on maps and in photographs, with the latter typically featuring canoes and tents. Ironically, the artificial island made of exotic rocks was one of the few spots in Seattle where Native people were tolerated, notes Coll Thrush in Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. In addition to being a stopping over point for tribes from outside the region who were headed to work the hop fields, Ballast became a refuge for locals, including several Native families that white settlers had burned out of their homes in West Seattle. By the late 1890s, Ballast Island had been subsumed by the growth of the railroads, and the Native people had lost this refuge. In Thrush’s sobering language, Ballast Island exemplified how “urban development and Indian dispossession went hand in hand.”

The archaeologists reached what they called Ballast Island deposits between about three and twelve feet below the present ground surface. Deposits included sand, silt, pebbles, and some brick and wood, as well as cobbles (size 3 soccer ball) and boulders of yellowish brown sandstone. They found no artifacts or other evidence of Native occupation. The Ballast Island deposits were up to about twelve feet thick and were underlain by beach deposits.

Although they didn’t do any geochemical testing to try to determine the origin of the rock—this wasn’t part of the required work of the dig—one of the archaeologists happened to be in San Francisco soon after the dig. Curious about the stone he had seen in Seattle, he walked over to Telegraph Hill. The sandstone looked exactly like what he had seen in Seattle. He was not surprised. Since San Francisco was the city’s earliest trading partner, rock from there was the original, and most abundant source, for Ballast Island. Individual ships dumped as much as 300 tons of rock and sand, from quarries on Telegraph Hill, into the water.

Curiously, none of the ballast collected during the Bertha digging was kept. All of it was put back where it was found. Part of the reason was that the archaeologists weren’t required to do so. Another part was concern from the Native tribes. Although Seattle’s original inhabitants ended up on Ballast Island because of horrible treatment by European settlers, the island still holds a place of importance to the Native community. Because of this WSDOT “want[s] to avoid this possible pile of buried stone like the plague,” wrote Knute Berger in an astute column in February in Crosscut.

Now that Bertha has moved ahead a few feet and is presumably on her way to being fixed (of course she isn’t and may not be but let’s be a bit optimistic at this point), it looks like no further archaeological work will be done. This is an unfortunate situation as digging up our past and learning more about the origins of the city could have made Bertha’s indigestion problems less troublesome and controversial, or at least turned them into something positive.

September 3, 2014

Seattle Map 2: Seattle = Scandinavia

As a researcher, one of my favorites sites to peruse is the Seattle Times online archive, where I can keyword search the newspaper for the years 1900 to 1984. (Unfortunately, access to the site is not unlimited. One way is if you have a library card from Seattle Public Library.) Recently, I came across a crazy map, published on page 24, July 30, 1916. The map superimposes a map of northern Europe on Seattle. It was produced by a G. E. Kastengren, a local insurance surveyor. As the article notes, Kastengren believed that it showed why “so many Scandinavians have been content to make the Puget Sound country their own.”

For example, Norway and Sweden align with Ballard and points north and the U-District and points north. The Gulf of Bothnia, which separates Finland from the rest of Scandinavia, fits pretty well with the northern end of Lake Washington. To the south, Elliott Bay stands in for the straits separating Denmark from its northern neighbors. Kastengren even points out how the University of Washington matches Uppsala University and how Sweden’s largest port, Gothenberg corresponds with downtown Seattle’s big port facility for the Northern Pacific RR. You can also see how the old city boundary of 85th Street runs along what would be the north 61st degree of latitude.

I don’t think the map was ever published any place other than the Times. Perhaps we can revive it somehow. It certainly provides some fun food for thought about our geography and our early day immigrants.

Seattle as Scandinavia

Material for for this story comes out of research I have done for my new book on Seattle – Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

If you so desire, you can like my geologywriter Facebook page.