David B. Williams's Blog, page 10

June 25, 2015

Seattle Map 14 – 1931

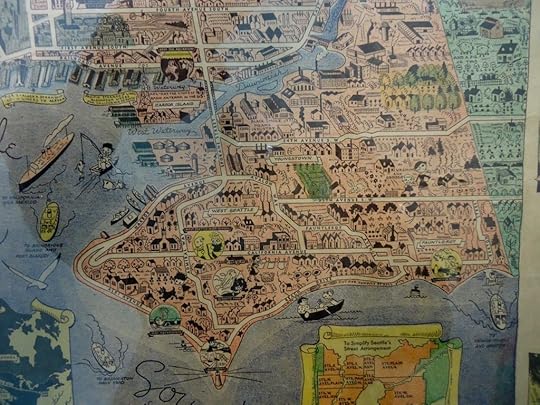

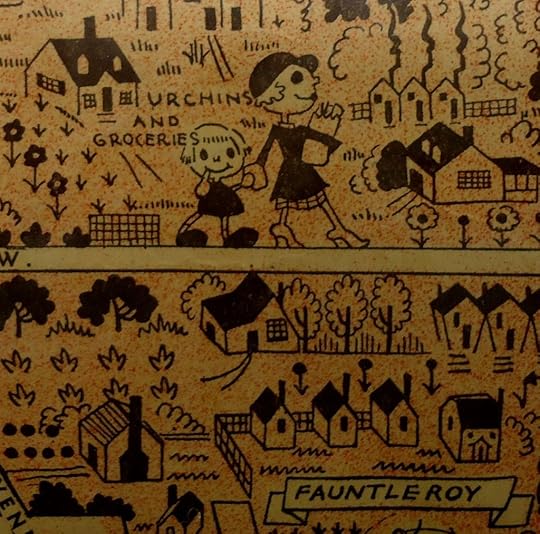

Recently I came across an unusual map of Seattle–Frank McCaffrey’s New Dogwood Map of Seattle, published in 1931. The map is a cartoon-style with curious depictions of monuments and locations in the city. Plus, east is at the top of the map. I am guessing that McCaffrey wanted to create a horizontal map but was dealing with a vertical, or at least north-south trending, city.

April 23, 1933 Advertisement

April 23, 1933 AdvertisementFrank McCaffrey was long time publisher/printer in Seattle, who owned Dogwood Press. His obituary in the Seattle Times (May 15, 1985) noted, “‘Business has too long been hamstrung by stupid politicians and their mismanagement of the people’s interests,’ McCaffrey asserted in a campaign attack against politicians during his unsuccessful 1936 mayoral bid. But he was undaunted by his loss at the polls. He again ran an unsuccessful campaign for mayor in 1946, and failed to win a county commissioner’s seat in 1944 and City Council seats in 1948 and 1961.”

If you are interested in seeing the entire map, copies are available at the University of Washington’s Special Collections and in the Seattle Room at the downtown branch of Seattle Public Library.

West Seattle

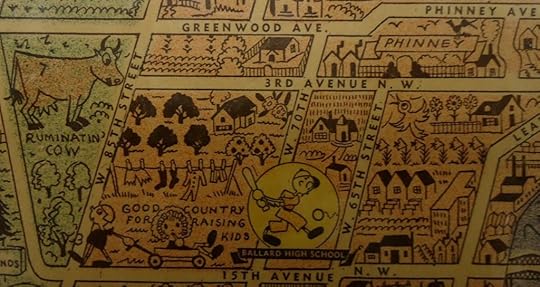

West Seattle A cow in Ballard

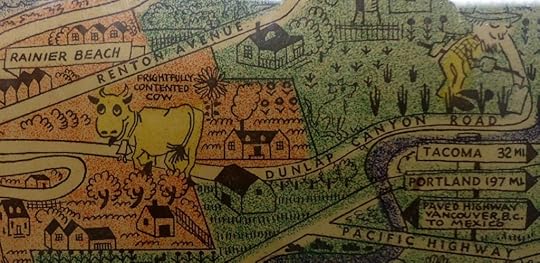

A cow in Ballard A cow in Rainier Beach

A cow in Rainier Beach Urchins? Wow, that’s a term you don’t see much anymore.

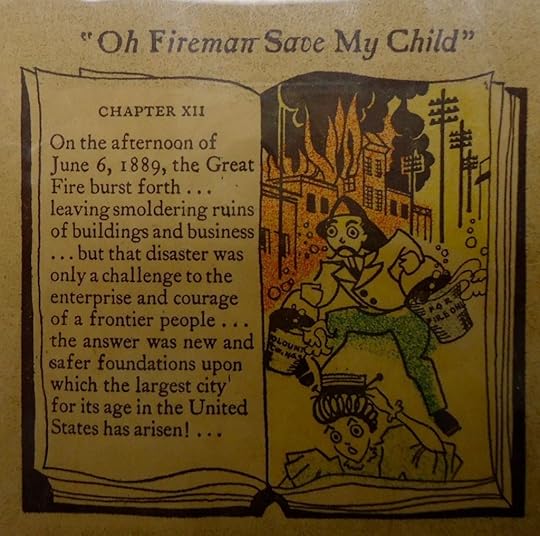

Urchins? Wow, that’s a term you don’t see much anymore. FIRE!!!! 1889

FIRE!!!! 1889

June 15, 2015

Geology Underfoot – Reading in Seattle

Just quick note about Dave Tucker’s talk tonight at 7pm at the UBookstore in Seattle. He’ll be talking about his wonderful and much needed new book, Geology Underfoot in Western Washington. Don’t be shy, come support Dave and independent bookstores. Congrats Dave!

June 9, 2015

Ammonites in Seattle

Last night I was fortunate to give a short presentation to the Cephalopod Appreciation Society. I wanted to follow up that talk with a guide to where to see ammonites in Seattle. Here’s the skinny.

Ammonite in Seattle

Ammonite in SeattleThe rock:

155 million year old Treuchtlingen Marble – It is actually a limestone because the rock has not been metamorphosed. During the Jurassic Period when dinosaurs roamed the land, a shallow sea covered much of Europe. Many critters from that sea are now preserved in the tan to gray limestone. When the animals died they settled to the bottom of the sea. The most common fossils are sponges, bottom dwelling, filter feeders that formed small mounds. They may be round, straight, or irregularly shaped and are darker than the surrounding limestone. The ammonites are the largest fossils. They are coiled-shell animals that resemble a top down view of a cinnamon roll. The biggest ones in the German limestone are about five-inches across, whereas the largest ones that ever lived were six feet wide. Ammonites swam the seas from about 400 to 65 million years ago, going extinct, along with dinosaurs, at the K-T boundary. Their modern relatives include squids, chambered nautiluses, and octopi. You can also find another squid relative, belemnites, which look like a cigar. They are dark brown and somewhat shiny.

Belemnite Fossil

Where to see ammonites in Seattle:

1. Cherry Hill branch of Swedish Hospital, formerly Providence Hospital (on East Jefferson St. between 16th and 17th Avenues) – Fossils are in the main building in the stone that makes up the floor.

2. SeaTac Airport – A/B Food concourse, walls are covered in Treuchtlingen.

3. Grand Hyatt Hotel – 7th Avenue and Pine Street – Floor of lobby and into hallway/lobby of conference rooms on ground floor.

Another ammonite in Seattle

Another ammonite in Seattle

May 20, 2015

Newly discovered erratic in Seattle

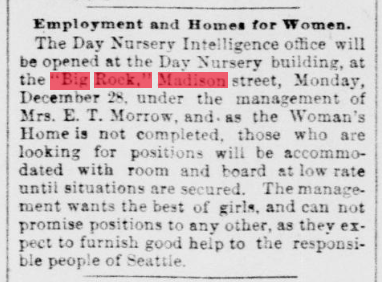

Okay, my title’s a bit misleading but I did just learn about this erratic, though it has not existed for over 115 years. I was doing some research on the early history of Madison Street when I came across a reference to what some called the “Big Rock.”

The rock was located on the south side of Madison Street at what used to be known as Williamson Street and is now Tenth Avenue. Basically it’s the northwest corner of the Seattle University campus. On October 29, 1892, an article in the Seattle P-I described the rock as measuring 64 paces around and 12 feet high. It was in the news because crews were getting ready to blast it as part of a grading project on Madison. (There used to be another “Big Rock” in Seattle but it suffered a similar though less destructive fate.)

The paper further noted that “this rock has long been a landmark in the city. The names of the streets in the vicinity being only a tradition.” If you wanted to tell someone where to meet, you’d simply say near the “Big Rock,” though you had to be a bit careful as the paper also included several notices about robberies taking place near the Big Rock. Apparently it was also quite the place for a little nineteenth century nookie, or maybe even a bit more, but as the P-I writer noted, “fortunately…the big rock tells no tales.”

tradition.” If you wanted to tell someone where to meet, you’d simply say near the “Big Rock,” though you had to be a bit careful as the paper also included several notices about robberies taking place near the Big Rock. Apparently it was also quite the place for a little nineteenth century nookie, or maybe even a bit more, but as the P-I writer noted, “fortunately…the big rock tells no tales.”

May 18, 2015

Mount Saint Helens: 35 years ago

As someone who grew up in Seattle and has lived here for the past 17 years, I, like many in the Pacific Northwest, have a long history with Mount Saint Helens. In junior high, we took a field trip to explore the volcano’s lava tubes. I remember wandering through the narrow passages and being excited at being inside a volcano. It was just a few years later, on May 18, 1980, that the mountain blew for the first since 1857.

I spent the day of the eruption watching TV and wondering about my brother who was driving home from college via Portland. We did not know for hours where he was. And nor did he know about the eruption. He and the guy he was traveling with couldn’t figure out why traffic had come to a standstill. It was both exciting and sad to follow the stories of that day and the months that followed.

As the mountain continued to erupt, we were lucky enough that the wind periodically blew north and carried ash into Seattle. It wasn’t much but we did get light coatings of ash on our deck.

My closest encounter with the mountain didn’t come until 24 years after the 1980 eruption when I wrote an article about its 25th anniversary. I was fortunate to spend two days on the mountain with Charlie Crisafulli, a biologist who has studied Mount Saint Helens since the eruption. The most astounding part was to walk across the Pumice Plain, the area directly in front of the crater, and to see how much life had returned to what had been an area completely lifeless in 1980. We found shrubs taller than us, toads, birds, snakes, rushing water, wildflowers, and many rodents. As life returned and biologists studied it, they were, and continue to, rewriting our understanding of how a landscape revives after devastation.

Studying Mount Saint Helens

Studying Mount Saint Helens Plants on the Pumice Plain

Plants on the Pumice PlainIn September 2004, a couple pals and I climbed the mountain. The next day we were going to meet up with a University of Washington geology class and hike up into the crater. They never showed at the meeting point, so we headed out across the Pumice Plain. The vegetation was even larger and more widespread. We didn’t go into the crater. Not until we got back home, two days later, did we find out that an increase in earthquakes had alerted geologists to the potential for the mountain to erupt again. Turns out that the mountain was closed to climbing the day after our ascent and just six days later it erupted again for the first time since 1986.

Post 2008 Crater

Post 2008 Crater Post 2008 Crater – Close up

Post 2008 Crater – Close upI have continued to return to Mount Saint Helens over the years. It is one of the most amazing places I have ever visited: an astounding combination of destruction and life, unfolding and ever changing. We in the PNW are incredibly lucky to have Mount Saint Helens in our backyard.

Looking back at the crater – 2013

Looking back at the crater – 2013

May 11, 2015

Mikado Street in Seattle

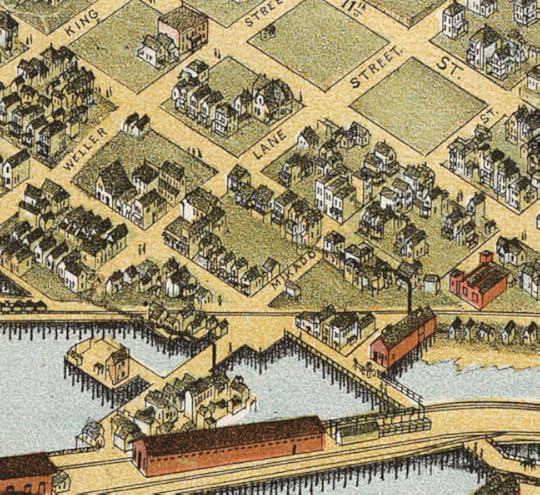

I have read in a variety of books, articles, and web sites that one of the earlier signs of the presence of Japanese in Seattle was the street name “Mikado Street.” The reference, I believe, is to Augustus Koch’s 1891 Bird’s Eye View of Seattle, which includes the street on it. Below is the map and here’s a typical line about the street. “Their [Japanese] influence can be seen all the way back to the late 1800s, when Dearborn Street was named Mikado Street.”

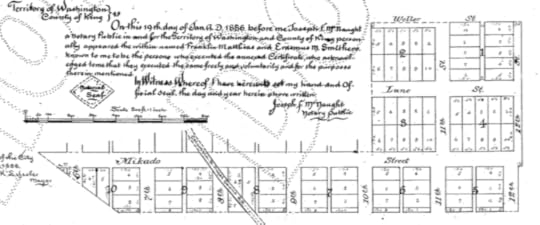

Close-Up of Mikado Street 1891 Koch Bird’s Eye

Close-Up of Mikado Street 1891 Koch Bird’s EyeAlthough this sounds credible, I don’t think it is correct to attribute the name to the presence of Japanese in Seattle. Mikado Street was named in 1886 as part of what is known as Terry’s Fifth Addition to the City of Seattle. Terry refers to Charles Terry, one of the Denny Party, or founding families of Seattle. He had owned large sections of Seattle, which his descendants later platted. This particular plat of Terry’s estate was planned by Erasmus M. Smithers (what a wonderful name) and Franklin Matthias.

Close up – Terry’s Fifth Addition

Close up – Terry’s Fifth AdditionWithin the legal description of the plat, Smithers and Matthias describe that all of the streets but one are prolongations of preexisting streets. Only Mikado is new. Nowhere do they state the origin of Mikado. This was typical, that the people planning the plat would either continue preexisting streets or come up with names for the new ones.

The main reason I think that Smithers and Matthias didn’t choose Mikado for its connections to Japanese immigrants into Seattle is that there were fewer than a dozen Japanese living in Seattle in January 1886 (Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America). Plus, I cannot find any connection between Japan and Smithers and Matthias.

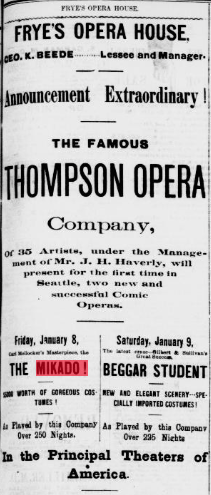

But 1885 was the year that Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera The Mikado debuted in London. It quickly became hugely popular. H.L. Mencken later wrote that by the end of 1885, 150 companies had performed the show. In December 1885, the Seattle P-I reported on the “Mikado craze,” with Mikado rooms being built in Manhattan mansions. Perhaps more relevant to Seattle’s story, on January 8 (10 days before Smithers and Matthias filed the plat), The Mikado opened at Frye’s Opera House in Seattle.

Of course, this is circumstantial evidence but it does seem more likely that Smithers and Matthias chose Mikado for the popularity of the opera than for an acknowledgment or honoring of the Japanese in Seattle. If anyone has other ideas, I would be happy to hear them.

In 1895, the city of Seattle changed Mikado Street to Dearborn Street. Section 276 of Ordinance 4044 (which changed more than one hundred street names) states: “That the names of Alaska Street, Mikado Street, Modjeska Street, Cullen Street, Florence Street and Duke Street from Elliott Bay to Lake Washington, be and the same are hereby changed to Dearborn Street.”

The Mikado – Seattle P-I, January 8, 1886

The Mikado – Seattle P-I, January 8, 1886

May 8, 2015

New books

Congratulations to two friends on their new books.

Dave Tucker‘s Geology Underfoot in Western Washington has its official book release on Tuesday, May 12, at 7PM, at the Whatcom Museum Rotunda Room in Bellingham. Dave will discuss the inside story of how the book came to be, tell how I put it all together, read a very short excerpt [he promises not to bore you], and sign books. Books will be for sale by Village Books, who is hosting the release along with North Cascades Institute and the Museum. For those who can’t get to Bellingham, Dave will also talk at the University Book Store in Seattle on Monday, June 15 at 7PM.

Priscilla Long‘s new book of poetry Crossing Over Poems will be out in July. Here are a few nice thoughts on her book.

“Memory is a bridge, poet Priscilla Long reminds us in this shimmering, elegantly-structured collection: these poems lead back to the bright sources of longing and grief, guided by Long’s excellent and playful ear, passion for language, and spine-tingling insights. Crossing Over interlaces elegies—including a gorgeous series for a lost sister—with remembered love, human tragedy, dreamy sensation, moody northwestern landscapes, and bridges—real and metaphorical. The joy of creation leavens every poem. I have long anticipated this book: it was so worth the wait.” –Kathleen Flenniken, erstwhile Poet Laureate of Washington State

“This is a poet obsessed with bridges and crossings, as the title of the collection implies: chaos to order; grief to acceptance; solitude to connection; confusion to understanding; life to death; past to present; dark to light–themes as old as poetry.”–Samuel Green, author of All That Might Be Done, Inaugural Poet Laureate of Washington State

April 28, 2015

Too High and Too Steep in the News

My pal Knute Berger has a thoughtful piece in Crosscut about Seattle’s “shape-shifting” landscape. Along with mentioning the wonderful Waterlines map produced by the Burke Museum, Berger writes in detail about my book, Too High and Too Steep, which will be published in September.

By the way, I just turned in the final page proofs for the book. Sort of crazy the mistakes found in the final read through of the book, such as 1900s when I meant 1800s, were instead of where, and my favorite, vice instead of vise, though this one would have been quite amusing.

April 27, 2015

Seattle Streams – Pt. 3

Here’s Part 3, and final part, of my posts about Seattle Streams.

Here’s a link to Part 2.

Here’s a link to .

Southwest Streams

Longfellow – Flows into Elliott Bay from West Seattle – John E. Longfellow homesteaded near the creek in the 1870s. He logged and farmed his property. The name Longfellow appeared on the 1894 McKee’s Correct Road Map of Seattle and Vicinity, making it perhaps the earliest official name for any creek in the city. It also is designated on the 1897 USGS Topo Map Seattle Sheet. But also see Thornton Creek, which is listed on an 1889 map but does not appear on these other maps, which were more widely distributed.

Puget – Flows off east side of West Seattle into Duwamish River – Named for park, which was donated to the city by Puget Mill Co in 1912.

Fairmount – Flows into Elliott Bay from northeast side of West Seattle – In 1907, J. W. Clise and S. F. Rathbun (Washington Trust Co.) filed a plat for Fairmount. According to old timers, the West Seattle Land and Improvement Company dammed the creek and pumped the water up the hill to supply water to the residents. A later article, however, noted that the drinking water came from Ferry Gulch, the next ravine north of Fairmount. (Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department, Seattle Times, July 29, 1934, Seattle Times, February 7, 1960)

Schmitz – West Seattle – German immigrant and one time commissioner of Seattle parks Ferdinand Schmitz and his wife, Emma, donated 30 acres to the city in 1908 so that it would be preserved as a park in perpetuity. (Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department)

Me-Kwa-Mooks – Flows into Puget Sound – Me-kwa-mooks is a rough sounding equivalent of a Lushootseed word (sbaqwabaqs) meaning prairie point or prairie nose. It refers to a vanished habitat that once dominated Alki Point. (Coll Thrush, Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place.)

Pelly – Just north of Fauntleroy.- Bernard Pelly came to Seattle in 1883 and worked with J.D. Lowman in many different businesses in Seattle, including real estate. Pelly later became the British Consul in Seattle. (Correspondence with Patrick Trotter, who is working on a detailed map of all the creeks in Seattle.)

• Gatewood - Tributary of Pelly Creek – Carlisle Gatewood was a real estate developer who arrived in Seattle in 1907.

• Eddy - Tributary of Pelly Creek – Unknown origin.

• Lowman - Tributary of Pelly Creek – James D. Lowman came to Seattle to teach in 1887. He later found Lowman and Hanford stationers. The Lowman and Hanford building is downtown in Pioneer Square area. (From Seattle Parks web site for Lowman Beach Park.)

Fauntleroy – West Seattle – Named for cove, named by Lt. George Davison in 1857, who took soundings. Name honors his friend and mentor Robert Henry Fauntleroy, an engineer for the U.S. Coast Survey and member of the New Harmony utopian community. Davison also named his brig after Fauntleroy, as well as naming Ellinor, Constance, and The Brothers peaks in the Olympics after Fauntleroy’s children. He later married Ellinor. Despite early naming of cove, creek name does not appear on any early maps of Seattle, though it is recognized as a name in city oridinance 20787 from April 1909.

Seola – South Seattle – The area was originally known as Kakeldy Beach, for the first people to build a house on the beach. Kids called the residents “Cackilty Chickens” so a contest was held in 1910 for a new name. Mel Miller came up with the name Se-ola, Spanish for “to know the wave.” (Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department)

Durham –Tributary of Duwamish River that entered near where State Routes 99 and 509 intersect – Also known as Lost Fork. Might be named for Leonard R. Durham, who lived in the area. The creek name has been in existence since at least 1937 when Mutual Materials applied for a Certificate of Water Rights to appropriate water from the creek.

Hamm – Flows into Duwamish River – Named for Dietrich Hamm, a German immigrant who arrived in Seattle in 1887. He was a large landowner in the area. In 1909, through his position on the Duwamish Waterway Commission, he advocated for straightening the Duwamish. (Seattle Parks history for Marra-Desimore Park)

Southeast Streams

Mount Baker – Assumed to be named for the neighborhood.

Mapes – Flows through Kubota Gardens in southeast Seattle – Henry P. and Eva Jane Mapes moved to Rainier Beach in 1902 and on October 9, 1909, platted the Mapes Fairview Addition. (Ordinance No. 22207) The Addition is where the modern Safeway sits. Good hints to a wet location come from historic street names in the platted landscape, Marsh Street and Cranberry Street.

Taylor – Flows into Lake Washington at Rainier Beach – Sanford Taylor established a mill one mile south of Rainier Beach on the shore of Lake Washington. His original mill had been near Leschi but a 1901 landslide that damaged the mill forced him to move south. It employed about 100 people. (University of Washington website photo of Taylor’s Mill at Rainier Beach, Seattle, ca. 1910, from Rainier Valley Historical Society Photography Collection)

Deadhorse – Creek also known as Taylor Creek – Various origin stories. Homesteader Charles J. Walker named it in 1909, after a beloved horse died in the canyon. Or trees felled in the canyon that were hard to move were called “dead horses.” Or a team of horses that were being used to move lumber fell off a road in the canyon. (Rainier Valley Historical Society, Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department, Seattle Times, August 19, 2004)

Hitt - Flowed into Wetmore Slough – Thomas Hitt was a fireworks maker in the area, with a fireworks factory on the hill just south of the Columbia City business district. Water from a fairly large spring on what was known as Hitt’s Hill flowed into the creek. (Correspondence with Patrick Trotter, who is working on a detailed map of all the creeks in Seattle.)

Wetmore – Joined with Hitt Creek to flow into Wetmore Slough. – Seymore Wetmore and his family arrived in Washington state in 1853 and helped started Seattle first tannery and shoe factory. They homesteaded in Columbia City in 1870. Early residents in Columbia City referred to the entire creek system, which included Hitt, as both Wetmore and Reservoir creek. (Correspondence with Patrick Trotter, who is working on a detailed map of all the creeks in Seattle.)

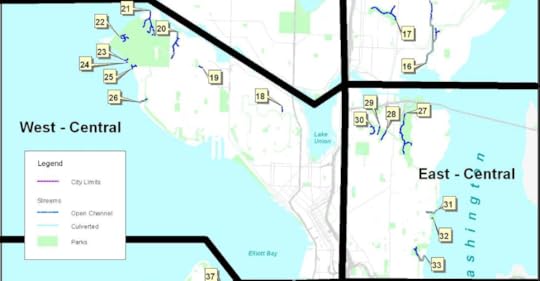

Southwest and Southeast Seattle Streams

Southwest and Southeast Seattle Streams

April 24, 2015

Seattle Streams – Pt. 2

Here’s part 2 of my Seattle Streams posting. Please do let me know if you find errors or want to help create a better map of Seattle streams.

West Central Streams

18. Mahteen – Queen Anne – Seattle Public Utility employees found a sign near the creek when doing work at the waterway. Name may be a corruption of a local Native American word.

19. Lawton – East side of Magnolia – Named after the nearby Fort Lawton Army Base, now Discovery Park. The base was named after Major General Henry Ware Lawton, who was known for his capture of Chief Geronimo in 1886.

20. Wolfe – When the organization Heron Habitat Helpers started asking neighbors in 2001 for a name of the creek, which flows into Salmon Bay, they were told it was known as Wolfe Creek. (Correspondence with Donna Kostka, co-founder of HHH.) Apparently, though, there were two creeks with similar names in Magnolia. Both flowed out of the bog that was formerly in Pleasant Valley. According to articles in the Seattle Times in 1911 (May 6) and 1912 (Nov. 15), Wolf Creek flowed south from the valley and drained into Elliott Bay. By 1946, the name had changed to Wolfe Creek (Seattle Times, April 7, 1946). Why there were two creeks with slightly different or the same name flowing in opposite directions from the same source is unclear.

21. Scheuerman – Discovery Park – In 1860, Christian Scheuerman homesteaded 160 acres in the Interbay area. He built the Scheuerman Block building at First and Cherry. When he died in 1907, he left an estate valued at $500,000. (Seattle Times, January 28, 1907)

22. Owl’s – Discovery Park – Unknown origin, though it seems logical to assume that some sort of owl was seen in the vicinity.

Ross Creek – Formerly the creek that ran from Lake Union to Salmon Bay, now the site of Lake Washington Ship Canal – John and Mary Jane Ross homesteaded the area in the late 1850s. He was a millwright and farmer. Eventually at least eleven families settled near by and the area became known as Ross. ( Historic Resources Survey Report: Fremont Neighborhood Residential Buildings)

East Central Streams

27. Washington Park (Arboretum) – Creek running through Washington Park Arboretum. Named for park.

28-30. Interlaken – Flows in park of same name – Interlaken has been around since at least 1905, though it is not known when the name was applied to creek. (Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department)

31. Madrona – Named for park, which was named in the early 1890s for a “few little (Madrona) sprouts” by J.E. Ayer, an early developer of the area. (Sherwood Files, Seattle Parks Department)

33. Frink – Flows into Lake Washington – John M. Frink arrived in Seattle 1874 and soon formed Washington Iron Works. In October 1906, he and his wife, Abbie, donated the land that became Frink Park to the city. At the time he was on the Board of Park Commissioners.

West Central and East Central Streams

West Central and East Central Streams