David B. Williams's Blog, page 7

October 1, 2016

HistoryLunch Talk

I was quite honored to have been asked to speak at HistoryLink’s annual HistoryLunch. Here’s the video of it.

September 6, 2016

The Seattle Files — Denny Regrade

Last weekend, I was honored to be part of the crew for Chris Allen’s The Seattle Files at Bumbershoot. It was a live show that was taped for a podcast. The other guests were John Keister (Almost Live) and Kate Jaeger (Jet City Improv). For the show we chatted about the Denny Regrade. I thought it was pretty fun. If you have some time, listen up.

August 23, 2016

The SS Roosevelt – From the Arctic to the Panama Canal

When the ship canal and locks officially opened on July 4, 1917, the epic boat parade was led by a legendary vessel, though it was a far different boat than when it earned its fame. The boat was the 184-foot Roosevelt, once described as the “strongest wooden vessle ever built.” Her strength was necessary because she was designed and built to carry Admiral Robert Peary’s crews to the Arctic. In 1909, Perry reached the North Pole, claiming to be the first to do so. (Historians debate as to whether Peary actually reached the location and whether Frederick Cook got there first.)

Peary’s ship, the S.S. Roosevelt, launches from McKay & Dix Verona Island Shipbuilding Co. on March 23, 1905. BUCKSPORT HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Peary’s ship, the S.S. Roosevelt, launches from McKay & Dix Verona Island Shipbuilding Co. on March 23, 1905. BUCKSPORT HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Roosevelt at Ellesmere Island – Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center at Bowdoin

The Roosevelt at Ellesmere Island – Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center at Bowdoin July 4, 1917 Ship Canal and the Roosevelt

July 4, 1917 Ship Canal and the RooseveltA little over a year after Peary’s men reached the Pole, the Roosevelt was sold to ship salvager and towing man John Arbuckle, After his death in 1912, the boat was sold three times in the next three years. By the time she reached Seattle in April 1917, the Roosevelt had been converted to a supply transport boat for the United States Bureau of Fisheries, which planned to use her in the Pribilof Islands. On her first trip there in 1918, the Roosevelt helped save several ships trapped in the ice in the Bering Sea.

After her service in the north, the Roosevelt bounced around between various owners, finally ending up with the Steamboat Inspection Service, where she was converted to a tug, her job till the sad end of her days. Her final voyage came in October 1936, when her new owner, the California Towing Company used her to tow a former Navy collier to New York. The trip did not go well with repairs in San Francisco and troubled trip to and through the Panama Canal. She left the canal in January 1937 only to suffer bad weather and numerous mechanical issues. She had to limp back to Cristobal.

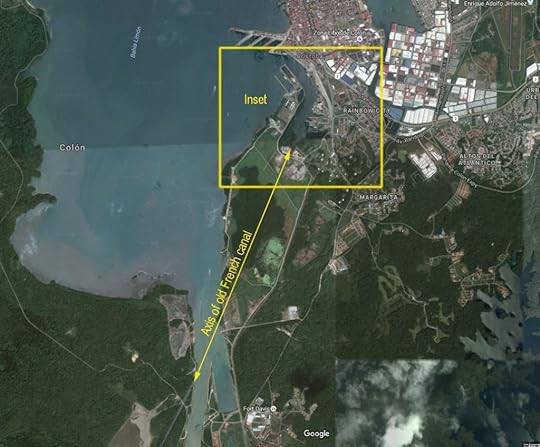

Finally on January 21, 1937, the Roosevelt was set out to pasture, so to speak, beached and abandoned on the tideflats of what was known as the Old French Canal. I have not been able to determine exactly what happened to the Roosevelt. The French attempt at a canal has been altered, cleaned up, and filled. Most likely the Roosevelt succumbed to the tropics and moldered and decayed away, one more relict lost to time.

Final Resting Place of the Roosevelt(?) – Used courtesy of Bill McGlauglin

Final Resting Place of the Roosevelt(?) – Used courtesy of Bill McGlauglin Close of final resting place – Used courtesy of Bill McGlaughlin

Close of final resting place – Used courtesy of Bill McGlaughlinBut a couple parts of the Roosevelt still exist. MOHAI has the ship’s wheel, a gift from one Karl Seastrom in 1954. The museum has no record of who he was or how he got the wheel. They also have some warning lights but again no data. The Roosevelt‘s bell is also in Seattle, at the Coast Guard Museum, though it is not the original one. That bell is supposedly at the Explorer’s Club in New York City. When I asked people at the CGM how they got the bell, I was told it was dropped off in the 1970s or 1980s by a former owner of the Roosevelt but who that was and how he got it is also unknown.

In case you are interested, here are links to more in-depth articles.

Julius Grigore, jr. “Peary and the Roosevelt: When Man and Ship Were One.” Panama Canal Review, Vol. 16, No. 5, August 1965, pp. 14-16, 22. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00097366/00029/18

NOAA Alaska Fisheries Service Center story: http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/history/vessels/boats/roosevelt.htm

From the Panama Canal Review, 1971: http://www.czbrats.com/Builders/FRCanal/frenchcan.htm

June 30, 2016

Lake Washington Canal Association

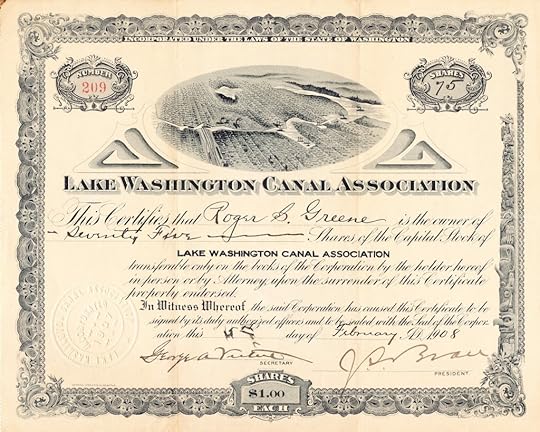

Yesterday, I was fortunate to meet Carol Whipple, great granddaughter of one of Seattle’s more important early citizens, Roger Sherman Greene. Greene had arrived in the state in 1870, when President Ulysses Grant appointed him to be associate justice to the Washington Territory Supreme Court. Greene moved to Seattle in 1882, where he became involved in civic politics and activities. In particular, he was well known for trying to prevent a lynching of two men in Pioneer Square and for standing up to white mobs during anti-Chinese riots in the city in 1885. Greene was also a principal player in the efforts to build a ship canal and locks in Seattle.

During our discussion, Carol showed us her ancestor’s personal stock certificate for the Lake Washington Canal Association. Formed in 1907 by people such as Greene, Thomas Burke, former governor John McGraw, and J.S. Brace, owner of the biggest mill on Lake Union, the LWCA was created to foster the building of the canal. It did so primarily by obtaining the rights to the canal, which had been given to developer James Moore. (Moore’s plan called for as single, much-too-small wooden lock, but he was unable to meet his obligations so transferred the rights to the LWCA.) The LWCA then transferred the rights to King County, which was responsible for building the canal.

During our discussion, Carol showed us her ancestor’s personal stock certificate for the Lake Washington Canal Association. Formed in 1907 by people such as Greene, Thomas Burke, former governor John McGraw, and J.S. Brace, owner of the biggest mill on Lake Union, the LWCA was created to foster the building of the canal. It did so primarily by obtaining the rights to the canal, which had been given to developer James Moore. (Moore’s plan called for as single, much-too-small wooden lock, but he was unable to meet his obligations so transferred the rights to the LWCA.) The LWCA then transferred the rights to King County, which was responsible for building the canal.

Holding the certificate was certainly my day’s highlight, though Carol’s story

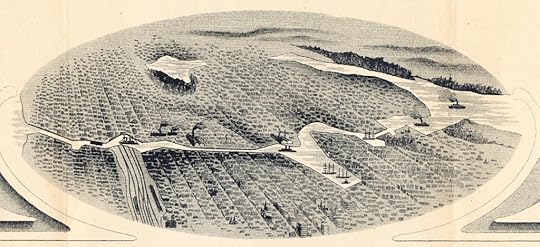

Holding the certificate was certainly my day’s highlight, though Carol’s story  about finding her ancestor’s glass eye in a collection of family memorabilia was a close second. It is a lovely document. In particular, the etching that shows the canal system is a true work of art, beautifully depicting Green Lake, Lake Washington, and the cuts at Montlake and Fremont. On the right side is another symbol of Seattle from the era, the totem pole that had been erected in Seattle in late 1899.

about finding her ancestor’s glass eye in a collection of family memorabilia was a close second. It is a lovely document. In particular, the etching that shows the canal system is a true work of art, beautifully depicting Green Lake, Lake Washington, and the cuts at Montlake and Fremont. On the right side is another symbol of Seattle from the era, the totem pole that had been erected in Seattle in late 1899.

Known as the Chief-of-All-Women pole, it had been carved earlier in the century to honor a Tlingit noblewoman of the Ganaxadi Raven Clan in southeast Alaska. The pole had made its way to Seattle when a group of Seattle businessmen had cut it down, stolen it, and brought it by ship to the city. In the words of the Seattle Post Intelligencer, it was “a great and wonderful thing and a grand acquisition for the city.” The pole would be burned down anonymously in 1938 and replaced with one carved in Alaska.

The LWCA ultimately succeeded in their goal. The canal officially opened on July 4, 1917, a date that is being commemorated this year and next.

June 27, 2016

Centennial Commemoration of the Locks and Canal

As I have noted previously, July 4, 2017, will be the centennial of the official opening of Lake Washington Ship Canal and the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks. I am part of a group — Making the Cut — that is working to commemorate this event. One member of the group is videographer Vaun Raymond, who is working on a documentary about the locks and canal. As part of this project, Vaun is posting a series of short videos.

The first one is now up and I am honored that he interviewed me for it and that he even included me in it. It is an introduction to the upcoming year of commemoration. Hope you enjoy it.

April 27, 2016

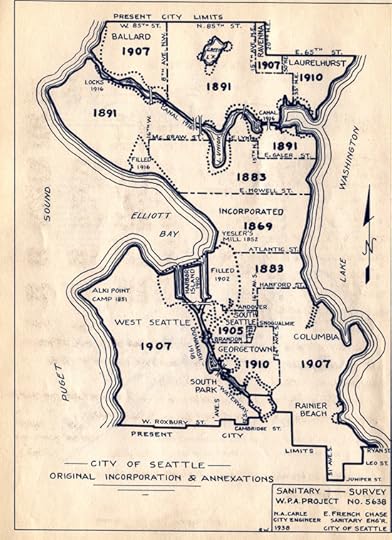

Annexing Seattle

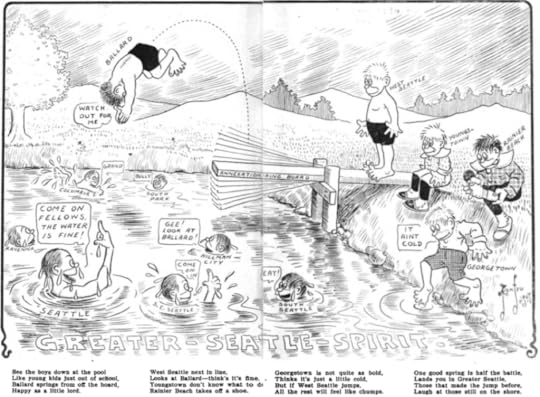

I recently came across this fine cartoon in a short lived magazine. Started in 1907 and published by the AYP Publishing Co, The Seattle Spirit Magazine: A Seattle Publication for Seattle People was created to promote Seattle and the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition. It was filled with bad poetry, songs, and jokes; photographs of the city; and articles detailing the city’s many assets.

Annexation from The Seattle Spirit, vol 1, no. 1

Annexation from The Seattle Spirit, vol 1, no. 1The image above refers to Seattle’s early growth, particularly the city’s aggressive acquisition/annexation of its surrounding towns, including Ravenna, Ballard, and Columbia City. Sometimes it’s hard to remember that what we now consider to be neighborhoods started life as towns often developed by an ambitious individual or two. Not all of the towns—Ballard exemplifies this trend—wanted to be annexed but there was little they could do as Seattle grew and prospered.

Annexation from Seattle Municipal Archives (Record Series 2616-03)

Annexation from Seattle Municipal Archives (Record Series 2616-03)Although 1907 was the biggest year for annexation, the movement continued for decades and still goes on. My pal Valarie Bunn has a thoughtful post on why it took so long to annex her Wedgwood neighborhood. And the Seattle Times‘s Daniel Beekman addresses the most recent fight over a city considering the positives and negatives of being sucked into Seattle.

March 22, 2016

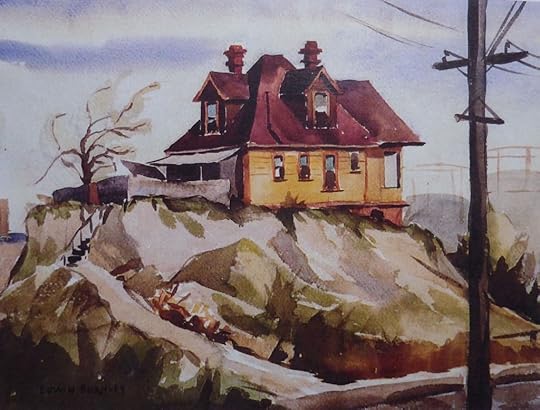

Last House Standing – Part 2

Late last year, I wrote a short post about the death of Curt Brownfield and the house where he lived on Denny Hill. I called it the Last House Standing because it was the final home to survive the regrades of Denny. Recently I came across a wonderful painting of the house and wanted to share it, along with another shot of the Brownfield home.

“The Hold Out” by J. Edwin Burnley from A Fluid Tradition

“The Hold Out” by J. Edwin Burnley from A Fluid TraditionThe artist was J. Edwin Burnley, who painted it around 1937. I learned of the drawing from A Fluid Tradition: Northwest Watercolor Society…the first 75 Years by David Martin. Burnley was born in Victoria in 1886 and arrived in Seattle a decade later. He later studied at art schools in Canada and was a president of the Northwest Watercolor Society and co-founder, with his wife, of the Burnley School of Art and Design, which later morphed into the Art Institute of Seattle. “Burnley devoted his professional career to teaching and arts advocacy,” writes Martin.

Little is known about the specifics of the painting, such as when exactly he painted it and what attracted Burnley to the house. The painting, which measures 14 x 18 inches and is in a private collection, though is an accurate portrayal of the Brownfield house.

Below are two other images of the house, both provided to me by Curt Brownfield. He told me that he had to carry firewood up the ramp, “usually by throwing pieces up the hill and throwing or carrying the rest of the way up the steps.”

Brownfield House – Pre-regrade

Brownfield House – Pre-regrade Brownfield House – Post-regrade

Brownfield House – Post-regrade

March 2, 2016

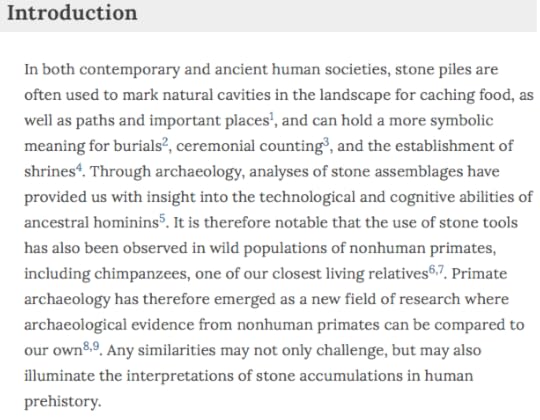

Nature and Cairns

Wow, a first for me. A book of mine (Cairns: Messengers in Stone) was referenced in an article in Nature. The article is titled “Chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing” and was written by a team of writers from around the world. They report on how chimps collect stones, bang and throw them against trees, and “toss them into tree cavities, resulting in conspicuous stone accumulations at these sites.” It is the first time any animal besides humans have been reported to do this.

I am honored that the authors cited me, and that they had even found my book, but I would like to point out that I sort of hypothesized such behavior in my book. On page 16, I wrote about the indirect evidence that Australopithecus afarensis used tools 3.4 million years ago. “If all Lucy (A. afarensis) did was pick up a sharp rock and slice a piece of meat for her lunch…surely she could have piled up a rock or two to let her family know where she was going or where she left that recently killed animal.”

I am honored that the authors cited me, and that they had even found my book, but I would like to point out that I sort of hypothesized such behavior in my book. On page 16, I wrote about the indirect evidence that Australopithecus afarensis used tools 3.4 million years ago. “If all Lucy (A. afarensis) did was pick up a sharp rock and slice a piece of meat for her lunch…surely she could have piled up a rock or two to let her family know where she was going or where she left that recently killed animal.”

An accumulation of stones in between buttress roots. Nature Science Reports 6, 22219

An accumulation of stones in between buttress roots. Nature Science Reports 6, 22219Here’s what the article says “Superficially, these cairns appear very similar to what has been described here for chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing sites, thus it would be interesting to explore whether there are any parallels between chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing and human cairn building, especially in regions of West Africa where the local environment is similar.”

Now, I have to admit I was being a bit facetious in my observation in Cairns but perhaps I wasn’t so far off the mark.

February 9, 2016

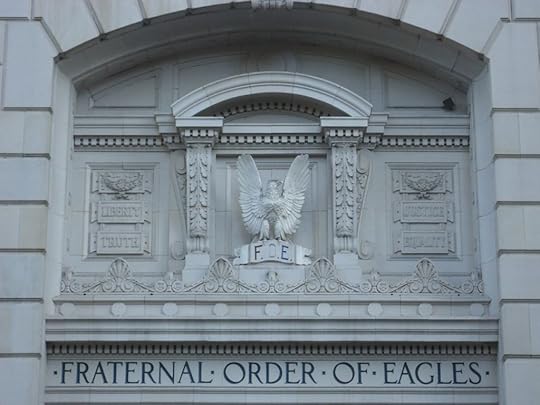

Birding in Seattle – Stone, Metal, and Terra Cotta

Seattle is well known for its abundant bald eagle population, with nearly two dozen nests in and around the city. The nests are generally in large green spaces, such as parks and greenbelts, but you can also find many eagles in downtown Seattle. In fact, there are more eagles downtown than any place else. And they are not alone. Several other species are found in the urban canyons.

Although none are real—they are terra cotta, metal, and carved stone—they are fun to find and see. Below are photographs of some of the several dozen eagles, as well as a few other species, a set of duck tracks, and one bird outside of downtown. Please let me know if you know of others.

Former Eagles Auditorium, now ACT Theater

Former Eagles Auditorium, now ACT Theater Eagle(?), Pelican, Gull (real) at 215 Columbia.

Eagle(?), Pelican, Gull (real) at 215 Columbia.  Another pelican at 215 Columbia.

Another pelican at 215 Columbia.  A duck in the frieze.

A duck in the frieze. And nearby the duck left its tracks.

And nearby the duck left its tracks. Former Seattle Times HQ on Olive between Fourth and Fifth

Former Seattle Times HQ on Olive between Fourth and Fifth Former Eagles Auditorium, Union St on Seventh

Former Eagles Auditorium, Union St on Seventh Eagles atop the Washington Athletic Club

Eagles atop the Washington Athletic Club Small metal adornment, First between Spring and Seneca

Small metal adornment, First between Spring and Seneca Water meter covers – Two friends think it’s a stylized cormorant. I think it looks more like a green heron or bittern. Any thoughts would be appreciated.

Water meter covers – Two friends think it’s a stylized cormorant. I think it looks more like a green heron or bittern. Any thoughts would be appreciated. Eagle and sun at 1411 Fourth.

Eagle and sun at 1411 Fourth. Plaza of Norton Building on Second between Marion and Columbia. By artist Philip McCracken.

Plaza of Norton Building on Second between Marion and Columbia. By artist Philip McCracken. South side of new Federal Building on Marion. Also by Philip McCracken.

South side of new Federal Building on Marion. Also by Philip McCracken. One of two owls on Tenth Avenue East at East Galer Street. The surrounding area used to be known as Owl Hollow.

One of two owls on Tenth Avenue East at East Galer Street. The surrounding area used to be known as Owl Hollow.

February 2, 2016

Locks Centennial

Today begins a 17-month-long commemoration of one of the great events in Seattle history. On July 4, 1917, the Lake Washington Ship Canal and Locks officially opened. It was the culmination of a multi-year project to connect Puget Sound to Lake Washington via Salmon Bay and Lake Union. I have written previously about this endeavor but would like to highlight one of the more significant, early construction milestones.

On February 2, 1916, fresh water from Salmon Bay entered the bigger of the two locks in the canal system. The lock was filled in 32 minutes with enough water so that it was equal to the level of Salmon Bay. As you can see from the second photo, there was enough pressure on the lock gate from Salmon Bay to push the gate open slightly. The February 3, 1916, Seattle Times called the event “the opening of the world’s greatest tidal basin.” (As you can see from the photo, snow covered the ground from one of the biggest snowstorms in Seattle history.)

Courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Courtesy Army Corps of Engineers Courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Courtesy Army Corps of EngineersAfter filling the locks, the Army Corps of Engineers opened the gates completely. This then became the route for tidal water to flow into Salmon Bay. At high tide, salt water would enter the bay and flood it. At low tide, water would drain out, exposing several acres of tide flats.

Prior to February 2, tidal salt water had entered Salmon Bay on the south side of the locks, where the present day spill gates are located. With the gates open, the Corps closed off the south side route and began to build the spill gate system, which is basically a dam helping to keep Salmon Bay at a constant level between 20 and 22 feet above sea level.

On February 3, the first boat, the Orcas, entered the locks and passed through to Salmon Bay. The locks would remain open until July 12, 1916, when the dam/spill gate was finished, and the Corps began to flood Salmon Bay with water from Lake Union. Salmon Bay would soon become the reservoir we now know.

Courtesy Army Corps of Engineers

Courtesy Army Corps of Engineers