David B. Williams's Blog, page 22

September 25, 2012

Cairn A Day 1

I thought I’d start a little feature I am calling a Cairn A Day. These are shots sent to me by friends from their various adventures. It seems a good way to share other people’s interest and observations of cairns. The first one is from my old pal Terry Knouff, who does wonderful work with Polaroid cameras. This shot is a cairn built as a marker for a uranium claim near the Moniker and Merimac Buttes, just north of Moab. It’s a wonderful illustration of how sandstone blocks allow one to build what I call a chimney cairn.

Cairn marking uranium mining claim, near Moab, Utah

September 6, 2012

Community of Man

Cairns are not always known as cairns. According to the OED, people who dwell in Cumbria refer to, or at least formerly did, a prominent pile of rocks as a man. The best reference for this use comes from Virginia Woolf’s dad, Sir Leslie Stephen, a famed mountaineer of the middle nineteenth century. His book, The Playground of Europe, was quite influential to several generations of mountain explorers.

Late in the evening on July 30, 1862, Sir Leslie and a group of friends were slightly misplaced while hiking near the Eggischorn in the alps of Switzerland. Fortunately, their shouts attracted a young boy who brought a torch to aid them. (It’s not exactly clear what he was doing up there but Sir Leslie doesn’t go into that detail.) But they still remained lost. Sir Leslie wrote “After scrambling up and down, and round and round for a long time, we found ourselves in a disconsolate and bewildered state of mind, standing on a damp ledge of grass at the foot of a big rock staring vacantly into blank darkness Whether to go up or down, or right or left, we knew no more than if we had been dropped into middle of the great Sahara.” Sir Leslie and his companions decided the best thing to do was to wait out the night. Just as he was adding more layers of clothes the boy, who had disappeared as mysteriously as he appeared, reappeared saying “I’ve found a man!”

It took Sir Leslie a few seconds, as he wrote, to “appreciate the fact that he was referring to a stone man or cairn, marking the route to the Eggischorn.” They eventually made it to safety and “two good bottles of champagne.”

Sir Leslie’s pleasure at the boy’s discovery of the cairn exemplifies one of the universal truths about cairns. Finding one when you are lost is truly memorable and one of the most reassuring things that can happen to you in the backcountry. It also exemplifies my thoughts that cairns carry more meaning than just being a simple pile of rocks. They are an important means of communication and a sign of community, for in such a situation as Sir Leslie found himself, he knew that those who came before had erected that man, or cairn, to aid fellow hikers, surely one tangible sign of a community: the desire to help others.

August 30, 2012

They’re here, there, and I hope everywhere!

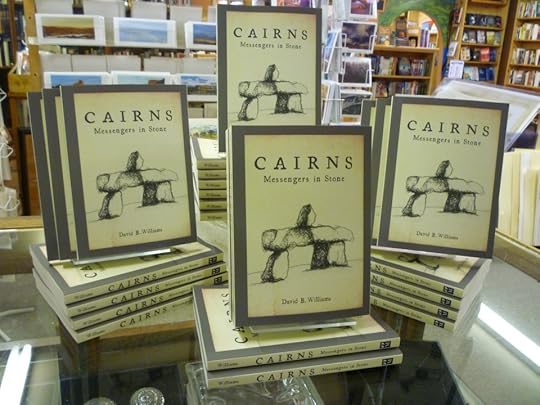

Golly ned, it’s hard to believe but my book is for sale. I am very excited. Thanks kindly Mountaineers Books and Back of Beyond Books in Moab.

Cairns is in stores.

August 20, 2012

It’s here – Cairns: Messengers In Stone

On Saturday, after returning from a short hike, I opened the front door and there was a package from my publisher. Inside was my new book, Cairns: Messengers in Stone. Pretty exciting to see it. I think it’s quite handsome and elegant. The drawings look better than I could have hoped and the layout is also nifty. It is smaller than I expected but has a nice feel to it. Certainly seems to me that it would make a fine present for most anyone! Stay tuned or go to my web site for more information on readings.

A Boy and His Book

August 13, 2012

Why rock? Why stone?

I recently received a nice email from another person passionate about stone and cairns. In particular, he sent me a link to his web site detailing travels in the United Kingdom to ancient megalithic sites. Wow, those folks way back then really loved their stone: standing stones, cairns, stone circles, henges, and dolmens. He also describes several stone features that I had never heard of: brochs (forts with hollow walls), quiots (a Cornish term equivalent to dolmen). If you have time to check out the site, I highly recommend it.

Looking at the photos got me thinking a bit about stone and its use by people all over the world.

Why did and do we still continue to use stone? Why not build commemorative cairns or henges or dolmens or monuments of sticks or bones? Some people did, but for the most part they chose, and often went out of their way to find, rock in which to make an offering. (There may have been more of these structures made out of organic material but they were lost to time.) The reason is no more complicated than the universality of stone. As the marketers would tell us, rock is everywhere you want to be. It is easy to pick up and comes in an infinite number of shapes, sizes, and colors. Once placed on a shrine, stone will not blow away, erode, decay, or suffer in foul weather, at least in human time periods. Nor will anyone covet it or steal it, which does not mean that cairns last forever. A ranger at El Malpais National Conservation Area in northern New Mexico told me that cows and other wildlife like to rub against cairns, which occasionally knocks over the piles. More than animals, though, people are the primary destroyers of cairns.

There is something else about stone though. “Above all, stone is,” wrote philosopher Mircea Eliade, in Patterns in Comparative Religion. To primitive man, nothing was more basic nor more noble than stone. Through its hardness, its power, and its permanence stone “transcends the precariousness of humanity,” Eliade wrote. Nor was stone of the profane world but of the sacred world. He cautioned, however, that men did not love stone because it was stone but because they could ascribe to it certain values and feelings. “Men have always adored stones simply in as much as they represent something other than themselves,” he wrote.

Our ritualistic use of stone occurs in part because stone is such a benign material. Unlike animate objects, stone has no personal history. It has no feelings or sentiments. It does not change. It just is, and thus we find it easy to ascribe a stone with a value, to make it sacred, to give it the capacity to possess a trait that can help or hinder.

Of course, one can argue that when people were building these megalithic sites, they had few other choices for building materials. But what about in modern times when the choices are so much more vast? As I have written before, stone still bewitches for at least three reasons. For starters, it is alive—a living, breathing material that changes gracefully over time. Second, it is natural, the ultimate in organic living—people may not know a particular stone’s origins but, unlike chrome and steel, they intuitively sense the link between it and the earth around them. And third, no two stones are exactly alike; every structure has a unique look, feel, and story.

All of these reason combine to make stone special: an enduring material valued for its many special properties. Long live stone.

And by adding our stone to others we reaffirm and get confirmation of this belief.

July 31, 2012

Big Spider Web

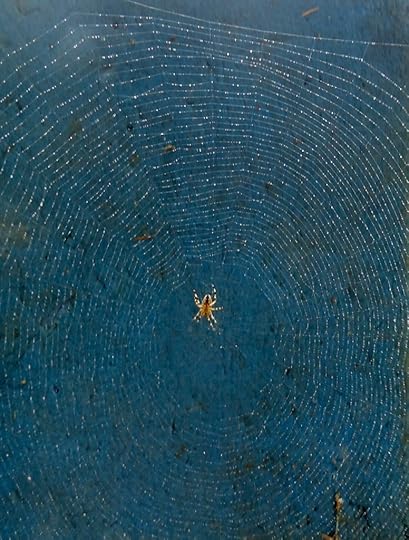

I like coincidences. Today in the New York Times there was nifty little Q and A about spider webs. The coincidence comes from the spider web that I saw in my back yard the other day. It was huge.

Modified Spider Web

Spider webs are everywhere this time of year and I am always getting webs in my hair or spiders crawling on my shirt, or even dangling off my face. I generally enjoy these encounters and do try to keep my eyes out for them. The other day, there was one spider I could not miss. The main body of the web was not so big. It was a classic Charlotte’s Web kind of web, beautiful in its detail and a marvel in its design.

Close up of web

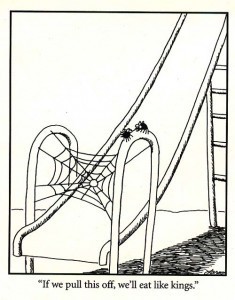

What caught my eye was the size. The web spanned an area covering more than seventy square feet. You can see it in the modified photo above. The red lines are an electrical wire and a clothes line. The yellow designates the web. Based on the NYT article, the spider must have ballooned, or kited three bridge threads and then built the web. It reminded me of one of my favorite Far Side cartoons. Unfortunately someone else walked into the web and destroyed and the spider hasn’t rebuilt.

Eat Like Kings

July 26, 2012

Follow up to Epidemic of Cairns

Around this time last year, I wrote a post about the proliferation of cairns in unsuitable spots, such as national parks. It generated a wee bit of discussion, which I tried to work into my book on cairns. Now, I have a fine follow up to the epidemic in Yosemite. Some pals of mine were hiking there recently and came across one of the cities of rock stacks. They thought it a bit odd and out of place but also felt they needed to respect what others had done.

Just before they had come across the piles, my friends had passed a group of young students (9-14 years old) on an outdoor/environmental education program. When the group arrived at the site, the instructors were clearly upset to see the rampant piles, telling their charges how bad this was. They then let the students destroy every stack of rocks. My friend said you could see and feel the joy the students had in taking down what they considered, or were told, was a desecration of nature.

While I do not like to see such gatherings of rock stocks, I wonder if the students’ wholesale destruction was any better. My friends didn’t stick around to see if the students then tried to “clean up” the area by relocating rocks to more “natural” settings. Nor did they hear what the instructors said. Did they mention the environmental issues and how moving rocks can destroy habitat? Did they mention how building these cairns can lead to others building more and more cairns?

It seems to me that the best way to address this issue is to encourage people not to create similar cairn gardens. If you must build an aesthetic cairn/rock stack, as opposed to a directional one, for whatever reason, try to remember that others will follow. Some may like what you do and copy you. Others will be upset and perhaps destroy them. Either way is bad for the environment.

July 17, 2012

Dickens and Geology

Recently, I have been reading some of Charles Dickens’ novels. The guy could write! His books are funny, atmospheric, rich in detail, both personal and geographic, filled with wonderfully named characters—Harold Skimpole, Bucket, Sarjeant Buzfuz, and Mrs. Jellyby—and insightful. My most recent read is Bleak House, which contains two splendid references to geology.

Bleak House cover, from first serial edition

The first is in the amazing opening paragraph.

“London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.”

Megalosaurus had entered the lexicon on February 20, 1824 at a Geological Society of London meeting, when William Buckland described fossil teeth and bones from a carnivorous reptile at least forty feet long and weighing as much as an elephant. In honor of its larger-than-life size, at least larger than any known land animal, Buckland named it Megalosaurus, the Great Lizard. His description was the first ever of what would soon be called a dinosaur.

Few probably truly appreciated Megalosaurus until two years after the first publication of Bleak House. On July 10, 1854, at the grand reopening of the Crystal Palace, the public got to see the world’s first life-sized models of dinosaurs, although very few people called them that. The most common descriptors for the models—Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus—were antediluvian beasts or antediluvian monsters. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ display was the opening of our long term love affair with dinosaurs.

Megalosaurus at Crystal Palace

The second reference is even better, at least for my focus on building stones:

“People objected to Professor Dingo when we were staying in the north of Devon after our marriage,” said Mrs. Badger, “that he disfigured some of the houses and other buildings by chipping off fragments of those edifices with his little geological hammer. But the professor replied that he knew of no building save the Temple of Science. The principle is the same, I think?”

I am not recommending that everyone go out and follow in Professor Dingo’s footsteps but it is noble thought and I was glad to learn that my passion for building stone has had a long and illustrious history. I have to admit though that I have been known to peel up layers of weakened sandstone and even splash vinegar on a building or two to test whether it was made of limestone or sandstone. I also joke about whacking off a building chunk or two when leading building stone walks but want to make it clear that I have never done so…yet.

July 9, 2012

Crab Orchard Sign in Tennessee

In June, I received a request from Ann Morphew, from Crab Orchard, Tennessee. She is a member of a citizen’s group helping to revitalize the Crab Orchard community park. They had a goal of creating sign posts around the paved walkway that encircles the playground-concession-court area. Ann asked if she could use some text from my blog post on the beautiful Crab Orchard sandstone, a multi-colored stone rich in swirls. She also hoped to use some of the photos, which former Science News geology writer Sid Perkins had provided to me.

The sign is now up in the park with some words from my blog and Sid’s photographs. I am honored and pleased that she chose to use some of what I wrote. I look forward to seeing it some day.

July 2, 2012

Final Battle of the Cairns

Living within sight of a famously tall mountain can engender a sense of local pride. So when someone questions the height of your mountain or raises the height of their mountain, sparks can fly. Or more practically and literally, cairns can go up. Such was the case in Colorado with Mount Massive and Mount Elbert. Elbert is officially taller, at 14,433, about twelve feet higher than Massive. Both are in the Sawatch Range.

For many years, however, fans of Mount Massive operated with the knowledge that their peak was actually the taller of the two. To make sure, they would go up on the summit and build a cairn, at least 13 feet high. Elbertophiles, who “knew” that their summit was higher, didn’t take to the Massive upstarts’ cairn-erections and they would hike up Massive and take down the cairn, which lead to the Massive people heading back for another cairn raising. And, so on and so on. Finally, at some point the feud fizzled.

But the height of Massive still troubled some locals. In the late 1930s, an official survey determined that Mount Massive was taller than Mount Rainier, pushing Rainier from down to the fourth highest peak in the lower 48. Washingtonians were apoplectic. Leo Weisfield, chair of the Washington State Progress Commission, was so incensed that he contacted the superintendent of Mount Rainier and asked if something couldn’t be done to return Rainier to its rightful place as the third highest peak. Weisfield proposed that the simplest way to deal with the issue was to erect a cairn on Rainier’s summit.

Even more irate was Col. Blethen, the publisher of the Seattle Times. In a front page editorial on August 25, 1939, he wrote “Mount Rainier is the tallest mountain in the United States.” He rested his argument on the how much the mountain rose above its base, not its actual height. Those three mountains (Whitney in California and Elbert and Massive in Colorado) that were said to be taller than Rainier didn’t deserve their status since their bases were so far above sea level.

“For some reason the public has supinely accepted official measurements of mountains from theoretical sea level as indicating their actual height…This is sheer nonsense,” huffed Blethen. “It is perfectly true that Mount Whitney and probably the two hitherto unknown Colorado mountains are more than 14,000 feet “high” in the sense that their tops are that much above sea level, but there actually is no mountain in the United States that is 14,000 feet tall excepting the one which rises straight and clear from the sea level to peak and that is Mount Rainier.”

Despite Blethen’s logic and Weisfield’s plan, nothing changed. Then in 1948, four Seattleites, as part of a service club, proposed to build a cairn atop Rainier. It would be 24-foot-high cairn made of rock and snow. Again, the superintendent of Mount Rainier rejected the request. In response, citizens in Mount Vernon, a small town north of Seattle, countered that they would be happy for the four Seattle climbers to come and build a 10,501-foot-cairn on a hill near Mount Vernon, making it the third highest peak in the state.

As someone interested a wee bit in cairns, I have been delighted to track down these stories of cairns and how important they are to people. Sure they may say that what their doing is all about making their local peaks bigger but I think they all they really desired was to find ways to go out and build more cairns.