Cathy Day's Blog, page 12

June 7, 2012

For Cole Porter’s Birthday: My Personal Playlist

If you think this is going to be all You’re the Toppy, ha! think again.

"Madame..."

[Follow the title links to hear the songs!] Supposedly, Cole Porter wrote this hilariously maudlin song on a dare: his friend Monty Wooley gave him the worst title he could think of and challenged him to make a song out of it. This was the result. It’s a “story song,” told by Miss Otis’ maid or butler (depending on the gender of the singer), and the plot is reminiscent of William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” I’ve linked to a particularly amusing rendition of the song performed live by Fred Astaire.

When you think of “Begin the Beguine,” you hear Artie Shaw’s swing reinterpretation, which is what made the song immortal. But the song Cole wrote in 1935 for Jubilee sounded very different, probably like this, and then it sort of languished around, waiting to be reinvigorated by Shaw. When Cole eventually met the by-then famous bandleader, he jokingly remarked to Shaw, “I’m glad to finally meet my collaborator.” Shaw reportedly replied, “Does this mean I get half of the royalties?”

Me and my nephew, 2005

Annie Lennox’s version of “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye.” I used to sing this song to my nephew as a lullaby. My sister tells me that for a few years, he liked to hear it when he was falling asleep. To this day, if I start singing the words, “Ev’ry time…” he gets a little smile on his face. It’s our special thing.

Mr. and Mrs. Fitch

A song few of you have ever heard of, I’m sure. Here are the lyrics. The story goes that Cole and Linda and their friends invented a fake couple of social climbers named Mr. and Mrs. S. Beach Fitch. They submitted tales of the couple’s European exploits to the gossip columnists, and soon, everyone who was someone in café society wanted to meet these interesting Fitches. The Porters had a good laugh about it and then killed the couple with a well-placed obit. Mr. and Mrs. Fitch’s rise and fall was immortalized in this song which appeared in Gay Divorce. I find it really interesting that Cole and Linda understood that social celebrity is a construction, that it’s a made thing. It reminds me of the cases of Andy Devine and J.T. Leroy and what these social experiments/inside jokes/hoaxes/performance-pieces say about the construction of literary celebrity, too. Interestingly enough, the song also inspired a play of the same name starring John Lithgow and Jennifer Ehle about two gossip columnists who perpetuate a similar hoax using digital rather than print media. The show bombed on Broadway, and really, the song isn’t really very good, but I love what the story behind the song tells us about Cole and Linda’s relationship to media, celebrity, and fame.

I love Sutton Foster’s awesomely choreographed tap extravaganza from Anything Goes. I had the good fortune to meet Sutton at Ball State in Fall 2010 as she was preparing for her role, and I can testify that she is indeed the most down-to-earth Broadway star you’d ever want to meet.

Linda: "...in the silence of my lonely room."

My favorite of his standards is probably “Anything Goes,” and this version from the biopic of the same name is certainly interesting from a writerly perspective. Cary Grant is Cole Porter (ha!) and he’s been invited back to Yale for some sort of reunion (ha!) and as he sits down to play a song, he senses that Alexis Smith (playing Linda) is in the audience. They haven’t seen each other for a long, long time, what seems like years (ha!). He doesn’t want her to know that he’s crippled (ha!). They leave the concert hall, and she sees him standing there, assisted by his canes, and as the music swells (ha!), she runs to embrace him. Roll credits. The scene was created to tap directly into the emotions of the audience, many of whom were welcoming home loved ones wounded in WWII. And boy, did it work. Still, I love this song, the melancholy rhyme of “boom” and “room,” the lilt of the hungry yearning burning inside of me.

Song I Don’t Like but Find Interesting Biographically #1. Judy Garland and Gene Kelly singing I like to think about Cole Porter as a little boy, walking out the door of his family’s mansion at Westleigh Farms, heading down the road to the winter quarters of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus to hang out with all the circus people. Maybe he even met my own great great uncle, Henry Hoffman, the elephant trainer. It’s possible. Their timelines in Peru definitely overlap.

Song I Don’t Like but Find Interesting Biographically #2. It was Cole’s first big hit, an incredibly sentimental tune that made him enough money so he could marry Linda. In much the same way that the film Night & Day struck a chord with soldiers returning from World War II, “Old Fashioned Garden” was a hit with soldiers coming home from the Great War. The video link features the house in Peru, Indiana that Cole said he was thinking about when he composed the song: his grandmother’s house just down the Frances Slocum Trail from Westleigh Farms.

Song I Don’t Like but Find Interesting Biographically #3. I don’t particular like Mabel Mercer’s singing, nor do I think that it’s especially tuneful. I just love the lyrics, the message of the song. I think nothing comes closer to capturing Cole Porter’s philosophy of life. I wrote about it more here.

“Lima”

And last but not least, Song I’ve Never Even HEARD But I Find Interesting Biographically #4, “Lima” which he wrote for his first Broadway musical in 1916, the doomed-to-failure See America First. As you might know, I renamed my hometown “Lima” in The Circus in Winter. I thought I was pretty clever. But of course, Cole Porter did it first.

“Lima”

Other towns you may boast of,

Other towns may have style.

But the town I know must of

Has ‘em all beat—a mile;

You may think you live well in

Budapest or Baghdad,

But the town that—I dwell in

Makes the other—look sad.

Lima’s the place

And I’d give a lot, I guess,

Back there to race

On a Limited Express!

Refrain

Li—ma! Li—ma!

Ease my pain for me, send a train for me, do!

Li—ma! Li—ma!

Hear me callin’, for I’m a-fallin’ for you!

I simply quiver—to drive my flivver

Along that lazy hazy crazy Wabash River

And if I ever, ever get home again,

Why, I never, never shall roam again,

For I’m madly in love with that Li-ma town.

Ha! Me, too, Cole Porter. Me, too. Happy birthday.

May 29, 2012

“Not Like the Rest of Us”: Ten Thoughts on Cole Porter as Native Hoosier

On Friday, June 1st at 6:30 PM, I’m going to be on John Strauss’ Indiana Public Radio show, Indiana Weekend, talking about Cole Porter’s hometown (and mine): Peru, Indiana. We recorded the interview last week, but I haven’t been able to get these remaining thoughts out of my head.

Extreme Makeover: Cole Porter Birthplace Edition

1. Cole Porter was born on June 9, 1891 in this house in my hometown of Peru, Indiana. When I was growing up in Peru, I knew Cole Porter’s birthplace as the rather shabby apartment building on the left. A few years ago, the police found a meth lab in one of the apartments during a raid. This generated some negative press, which led to a wonderful effort to save the house and turn it into a B&B. Today, that house is for sale. The reason it’s for sale is that despite being absolutely beautiful and historical, the B&B doesn’t generate enough money because not enough people have reason to stay there. The whole thing makes me sad. Read this article if you want some backstory on this.

2. I lived in Peru, Indiana from 1968 until 1987, and during that time, I had no knowledge whatsoever of who Cole Porter was, nor that I shared a hometown with one of the 20th century’s most prolific composers.

3. How could I not know this? Because I’m working class. Because I grew up in town with no bookstores, no NPR stations, no record stores, no internet. Because no one I knew ever talked about him. Why didn’t they talk about him? See #5.

This is how I found out who Cole Porter was.

4. I had to travel all the way to New York City to find out that I shared a hometown with Cole Porter. It was 1990, I was shopping for music in Tower Records. I came across a tribute album called Red, Hot + Blue, a tribute to someone named Cole Porter to benefit AIDS research, and it contained songs by some of my favorite artists at that time (Sinead O’Connor, U2, Annie Lennox). So I bought it. I realized I knew all the songs already…somehow. I opened up the jewel case to read the liner notes, and right there, “Cole Porter was born in Peru, Indiana…” I was dumbfounded.

5. The next time I visited Peru, I asked my maternal grandmother, a member of the local historical society, “How can it be that I grew up in this town and didn’t know who he was? Why don’t we celebrate him more?” She said, “Well, it’s because he left, of course. And because, you know, he was…” She either said he was “queer” or “different.” I can’t remember which.

6. Today, Cole Porter is definitely celebrated and known in Peru. Proof of this:

his name is now on the “Welcome to Peru” sign (it wasn’t when I was growing up)

the Cole Porter Festival (go to this if you can!)

more exhibits devoted to him at the local museum, including one of his trademark Cadillacs

there’s a sign to help out-of-towners find his gravesite at Mount Hope Cemetery

My prized possession

7. Here is a T-shirt from a past Cole Porter Festival in Peru. I love this shirt and everything it represents, the question it raises: How do you celebrate one of the 20th century’s most sophisticated artists in a place where his brand of sophistication and artistry is not generally valued?

8. Things I have heard people from Indiana say about Cole Porter:

“His music has nothing to do with Indiana. It’s like he’s ashamed of us.”

“He never came back because he thought he was too good for this place.”

“He wasn’t like the rest of us.”

“I know he visited his mom a lot, and he had a standing order at Arnold’s Candies, and yeah, he’s buried here, but he’s not really from here, you know what I mean?”

“I guess Cole Porter’s B-day was today. Does anyone still listen to him?”

9. For 20 years, I lived as an expatriate Midwesterner. I was what writer Calvin Trillin calls an “ExMid,” a term he uses to denote “someone who lives on either coast or abroad but still prefers to think of himself at least partly as a Midwesterner.” The ExMid harbors a particular fear: “The fear that his mother or aunt or cousin will be cornered by some neighbor at his hometown supermarket and informed that he has become too big for his britches.” Cole Porter was not an ExMid, but I am. Big time. In fact, I am petrified that my aunt will be cornered at Harvey Hinklemeyers by one of her neighbors who will have read this blog post and tell her it’s really a shame I couldn’t find something nice to say on Cole Porter’s birthday.

10. What is the most Hoosier song Cole wrote? If by “Hoosier,” you mean sentimental and nostalgic, then by all means, it’s “Old Fashioned Garden” or “Don’t Fence Me In,” but if you mean a song that represents his “true” feelings about his Midwestern roots, then I say it’s the little known ditty “Experiment,” written in 1933 for the musical Nymph Errant. A professor gives some final advice to his graduating students about what to do in the face of “philistine defiance.”

Experiment.

Be curious

Though interfering friends may frown.

Get furious

At each attempt to hold you down.

If this advice you always employ

The future can offer you infinite joy

And merriment

Experiment

And you’ll see.

Happy Birthday, Cole.

May 21, 2012

10 Things You Should Know about the Midwest Writers Workshop

1. The Midwest Writers Workshop, or MWW for short, happens in my town! A few miles from my house! Muncie, Indiana, July 26-28, 2012.

1. The Midwest Writers Workshop, or MWW for short, happens in my town! A few miles from my house! Muncie, Indiana, July 26-28, 2012.

2. MWW’s faculty this year includes a Pulitzer finalist, a paranormal romance YA author, four literary agents, a best-selling author of cozy mysteries, a poet/memoirist/indie publisher, and quite a few long-time editors and publishing professionals. Including Jane Friedman, who I’ve been following for three years (long before I moved to Muncie) and who I credit with saving my writerly butt from literary oblivion.

3. MWW has been around for a long time: 39 years! Last year, I was on the faculty. This year, I’m the newest member of the Planning Committee. Some of the committee members have been working to make this conference happen for over 35 years. You can read more about the history here.

The Ball State Alumni Center.

4. MWW is the only writers conference I know of that offers on-site, totally free “social media consulting”—a drop-in tutoring center where you can get your Facebook/Twitter/blogging act together.

5. Veronica Roth, author of the best-selling, dystopian YA novel Divergent (which is really, really good) got her start at MWW. My fellow committee member Kelsey Timmerman also got his start at MWW. He attended a few years ago, pitched his idea to an agent, and thus his book became a reality: Where Am I Wearing: A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People That Make Our Clothes. There are many other success stories.

6. Remember when I wrote about how anxiety-inducing AWP is? Anxiety + Community = AWP. MWW, on the other hand, is small, intimate, encouraging—nothing at all like AWP. It’s open to anyone. You don’t have to apply to get in or secure a letter of recommendation.

7. Remember when I wrote this post about how much I hate it when people ask me “How do I get published?” Well, here is your answer: Expand your circles! Get thyself to a writers’ conference! Here are a few other good reasons to go to a writer’s conference.

Jane Friedman, middle, and MWW director Jama Bigger, right

8. If you read this blog because you teach creative writing, listen up. If you have strong students, don’t think that sending them to an MFA program is the only way to help them pursue their dream. Send them to MWW. Remember a few months ago, I asked, Should we make it our business to teach the business of creative writing? The response to that post was a resounding, Yes. Writers conferences are one way we can teach our students about the “biz.”

9. If you read this blog because you’re an aspiring writer, listen up: I know you write and read and edit alone. You go online to find community and advice about what comes next. But you need to find community IRL. You need to stop Googling “How do I publish a book?” You need to fork out some dollars, because believe me, there’s nothing like spending some money to help you start taking yourself a little more seriously. You need to actually show up to an actual brick and mortar building where others like yourself have also shown up.

10. I know I said this already, but this conference is in Indiana. Not in Boston or New York or even the bucolic Florida Keys. It’s in Muncie, Indiana. One reason why I left Indiana 20 years ago is that I believed you HAD to leave Indiana in order to be a writer (or an artist of any kind), but I came back two years ago because I wanted to help the next generation of Hoosier artists realize their dreams and become the people they want to be. When you’re poor or working class or live in a place where there isn’t a lot of literary activity, it’s not that easy to imagine yourself “becoming a writer.” That’s why bringing the publishing world to Indiana matters. A lot.

Will I see you there? This summer? Next summer for the 40th anniversary? I hope so. And do you know someone in the Midwest who wants to be a writer? Send them this link. Thank you.

May 7, 2012

What They Wrote About: This Novel-Writing Teacher Reflects

Here are the (purposely vague) premises of all the novels my students wrote this semester. I have indicated the writer’s gender thusly: (Italics = Male writer, Regular = Female student), and I’ve grouped the descriptions to reflect the particular critique circles I formed and placed them in. Meaning students in Class 1, Group 1 read each other’s manuscripts ONLY.

Class 1, Group 1

Sci-fi novel about revolution on Earth colony on Titan.

Sci-fi novel about man and android bromance. Huck Finn in space.

Fantasy novel. Squirrels, snakes, owls face civil war and obliteration of their peaceful land.

Class 1, Group 2

Coming of age novel about two girls, childhood friends from different sides of the tracks.

Two college lovers reunite in their mid-20′s quite erotically. #20ShadesofGrey?

Mother-daughter story, mom wants to break the cycle, but the circle wants to be unbroken.

Class 1, Group 3

Coming out in the 70′s, still feeling the effects in the here and now

Coming-of-age novel set in rural Indiana in the 70′s about a teenage girl whose parents abandon her. Survival story.

Female detective gets caught by the killer she pursues. Gritty, harrowing stuff.

Femme fatale snares men in her web, until one fights back. Thriller.

Class 1, Group 4

Best title: Completely Predictable Novel about Meaningless Experiences in Chicago (Actually the title is longer…)

House full of hipsters/recent college grads/artists/writers must face the future.

Epistolary novel, lifetime of letters written by a woman, a bit like Fair and Tender Ladies.

Class 2, Group 1

High-fantasy novel about a young man who learns he’s the true heir and the girl whose visions tell her she must help him.

In a small town shopping center, the lives (and fates) of a close-knit group of store employees become forever linked.

A half-elf/half-human boy and his other “half-breed” siblings leave on an epic journey and experience prejudice at every turn.

Class 2, Group 2

A teenage girl discovers her scientist parents have turned her into something unimaginable, and she and her best friend must find a cure.

Young demon trapped in the human world, must go to work for “Men in Black” type organization.

Shadowhunters try to prevent the Apocalypse.

Class 2, Group 3

Young love feels perfect but goes all wrong.

Girl travels across the country to attend Woodstock with the boy of her dreams. It’s perfect—until it all goes wrong.

Indiana girl takes care of everyone—her mother, her sister, her best friend—but finally learns how to take care of herself.

Class 2, Group 4

Three-time lottery winner dies and leaves this in his will: Whoever builds me the best tomb gets all the money

Seven galactic criminals survive execution and come to terms with their crimes and pasts.

Occupy Movement as 1984-ish satire. 1% character + 99% character join forces.

Class 2, Group 5

Gay man becomes politically active, loses his best female friend, hits bottom. Narrative + recipes + questionnaires

Elderly gay man is on his death bed. His husband gathers the family together. Told from 7 POVs as the clock ticks down.

High school girl struggles to survive her father’s violent nature—first all on her own, then with the help of friends.

Some Observations

I saw an uptick in the number of manuscripts with gay themes, subject matter, and/or characters.

I saw an uptick in the number of women students writing stories from a decidedly female perspective.

I saw an uptick in the number of novels that were largely commercial in premise, genre, and/or approach.

Remember: on the first day of class, I tell my students 1.) to write the book they want to write—no genre or subject matter restrictions, and 2.) they won’t have to show this manuscript to the whole class, just to me and a small group of sympathetic readers.

This upticks + the removal of the “all-class workshop” indicates to me that my students took risks because they felt safe doing so.

Many of my female students say that they were “inspired” by the Twilight books. Only one or two meant this in a positive way. Most told me that the quality of the writing in Twilight convinced them that surely! they could write a novel as well or better.

The first time a female student told me this, I downloaded the Twilight saga to my Kindle. And realized that my student was almost right: she did write better, sentence for sentence. All she needed was a better grasp of plot and theme.

In their practice query letters, only a few of my students self-identified their novels as “literary.” Most said “commercial” or identified the specific genre in which they were writing.

In one of our weekly online discussions, my students expressed many opinions about the distinction between literary fiction and commercial fiction.

In some cases, they know the difference between literary and commercial, and they think such distinctions are bogus. But in other cases, they really don’t know the difference. Sometimes it’s because they haven’t read enough yet, haven’t been exposed to enough contemporary literary fiction that they LIKE.

I grew up in a small town in Indiana where the only place to buy a novel was the grocery store, which means that the only novels I really “saw” growing up were published, marketed, distributed as commercial fiction. Like many of my students, I didn’t know what literary fiction was until I went to college.

I worry (perhaps too much) that the only reason my students don’t all self-identify as writers of literary fiction is that:

they believe they aren’t smart enough/good enough

that people from places like Indiana don’t write the “great” books

that to publicly declare their artistic aspirations would be to break the Cardinal Rule of the Midwest: Thou shall not think too highly of oneself.

all of the above

By teaching novel writing, I have realized that it’s not my job to turn my students into perfect replicas of me.

By teaching novel writing, I have learned much about my own long-standing, mostly unconscious prejudice toward commercial fiction. And I have come a long way in getting over it.

To teach novel writing is to open the door to commercial fiction.

My students think too commercially too early. Some students came to me and said they wanted to change their premise because “my group said it was too YA” or “my group said this was too chick lit.”

These students were all women.

No male students (that I know of) were told their novels were too YA or even too sci-fi.

I purposely did not put the young women writing stories about love and relationships into the same group as the young men writing sci-fi and satire.

Many women were writing novels about young women whose primary goal was securing male love and affection. When I pointed this out to one young woman, she said, “Oh my God, my character is Bella! And I hate Bella!”

If you teach novel writing and there are young women in the class, you must be familiar with these four names: Buffy, Hermione, Bella, and Katniss.

At least now, I understand the humor of the following exchange!

Katniss: So, how was everyone’s week?

Hermione: Oh, same old. Quidditch match, Ron being a whiny, emotional middle-child, a few random assassination attempts by the Dark Lord, saving Potter from certain doom. Y’know, the usual stuff.

Buffy: I was saving the world.

Katniss: I was also saving the world!

Bella: I jumped off a cliff to get the attention of my ex-boyfriend.

The two young men in Class 1, Group 4 are writing novels about love and relationships. But I did not describe their novels to you in that way to you, did I? All I said was:

Best title: Completely Predictable Novel about Meaningless Experiences in Chicago (Actually the title is longer…)

House full of hipsters/recent college grads/artists/writers must face the future.

Why didn’t I put these two men in the same group as the women writing novels about love and relationships? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but I definitely need to think about it.

I showed a few students (male and female) this video of “The Bechdel Test,” which asks student to consider these questions:

Does your story contain at least TWO women?

Do they talk to each other?

Do they talk to each other about something other than men?

This worked wonders.

I would separate my novel-writing students into three groups: 1.) those who are skilled at the story level but weak at the sentence level, 2.) those who are skilled at the sentence level but weak at the story level, and 3.) those who excelled at both.

My class focuses almost exclusively on the story level, but I make sure that those in Group 1 (the majority) know that they must work on their sentences if they want to be published.

The class is the hardest for those in Group 2, the kind of student who typically excels in a creative writing course, the kind who can write a great sentence but struggles with plot.

I made sure that every single student in Group 3 knows they are special and talented.

When I described my class to a friend, she said, “Man, I feel sorry for you!” Seriously: you can’t read the first 50 pages of 28 still-raw novels with resentment or disdain. You’ve gotta find a way to be excited about them, or you’ll go insane.

I teach this course, Advanced Fiction, at Ball State pretty much every semester, sometimes multiple sections (capped at 15). I don’t know if I have it in me to teach it as “novel writing” every time, forever and ever anon. It’s incredibly difficult to hold that many novels in my head during the course of a semester.

However, I’ve spent years figuring out how to teach this course, and I feel like it’s finally working.

Is there anything you’ve learned or observed? Please let me know. Thanks for reading, and have a great summer writing your Big Thing!

May 2, 2012

My Students: Writing as Fast as They Can

I want to introduce the two students who won the Total Word Count Challenge in my novel-writing classes: Sarah Chaney and Kayla Weiss. Each of these young women wrote over 42,000 words this semester, or about 3,500 words a week for 12 weeks. What’s significant about this is that they were only required to turn in 2,250 words per week—an assignment called “Weekly Words” which I talk about in detail here—but they both exceeded that amount…and then some.

Observations

I’d say that half of the students who took my class this semester walked in the door with a definite idea for a novel they very much wanted to write, and Sarah and Kayla were certainly in that group.

I remember at the beginning of the term, Sarah came to my office and said how much she was looking forward to the course. For years, she’d been trying to figure it out on her own, and as much as she liked her writing classes, she hadn’t learned the one thing she thought she’d learn as a creative writing major: how to approach the writing of a novel.

Unlike past semesters, this term I broke the process of writing a novel down into its component parts (you can check out my syllabus here), organized them into weekly units, and taught from a series of power point lectures.

I saw light bulbs going off over Sarah’s head quite often, but I noticed that Kayla hardly ever looked at me at all during my lectures. She just kept typing furiously. I asked her once, “Are you listening to me?” and she assured me yes, that she was taking notes. “The things you’re talking about help me understand what I need to do with my novel, and I want to write it all down while it’s in my head.” I believe her, but it would be hard to blame her for writing her novel during what I hoped were inspiring novel-writing lectures.

What were their novels about?

All my students had to write jacket copy and query letters for their works-in-progress, and this is what Sarah and Kayla’s novels are about.

Sarah Chaney

Sarah Chaney: 42,911 words

Novel: From My Perspective

All Mati wants is to graduate from high school without doing the one thing her mother fears the most: getting pregnant. She wants to go to college, get married, start a life and then have a baby, which is the exact opposite of what her mother, Amy, did.

Amy works three jobs to support Mati and struggles to find time to write, refusing to give up her dream to be a writer. Years ago, her family told her they’d cut her off if she had the baby, and as much as she loves her daughter, it’s hard sometimes to wonder if she did the right thing. All she wants is to save Mati from having to make the same hard decision.

But when Mati is assaulted and becomes pregnant, all bets are off. Mati’s attempt to hide her pregnancy (and rape) is short-lived, and she finds her future and the future of her child dictated by her mother’s ultimatum. At the same time, Amy’s doctor delivers horrible news, which causes her to rethink the life she left behind and the dwindling possibility to live her own life.

Now mother and daughter must untangle what it means to be a family in a world that emphasizes self-discovery and individuality. Can Mati figure out what she wants for herself, and will Amy be able to accept the unexpected ways in which life unfolds?

Kayla Weiss

Kayla Weiss: 42,008 words

Novel: Give Me A Sign

James Warren is a father, a husband, a brother, and above all a Shadowhunter – a special breed of human descended from angels. Six years ago, James was leading a normal life with a normal job, completely unaware of the secret life he was meant to lead.

The war between good and evil continues, with more and more Hunters falling in the line of duty. Alongside his brother, Will, his wife, Annie, and his guardian angel, Mel, James is the key to the Apocalypse. Now he must pick one side or the other. Good or evil.

Now, after the death of a Hunter very near and dear to his heart, James slips into a dark depression, locking himself away from the rest of the Hunters in the farmhouse, plotting his own path in the Apocalypse. With one last swig from his bottle of whiskey, he walks out of the farmhouse, with no intention of returning, to face his destiny. Which side will James choose?

I’m proud of ALL my students this semester, but I thought I’d highlight these two for doing exactly what I asked them to do: start writing a novel as fast and as well as they could.

Runners up

ENG 407-003

Ryn Bailey: 35,630 words

Phoebe Blake: 35,244

Jordan Martich: 30,064

Maye Ralston: 29,433

407-002

Kellie Suttle: 37,634

Mo Smith: 35,118

Tyler Fields: 34,780

(so close! let’s call it a tie)

Erynn Ellsworth: 32,720 and Sarah Tadsen: 32,365

April 30, 2012

Last Lecture: “Am I a writer?”

At the end of the semester, I give presentations in my novel-writing classes about the publishing business. Many students are seniors getting ready to graduate. Hence, they are full of anxieties. The first thing they say is: Why didn’t anyone teach us about this sooner!

At the end of the semester, I give presentations in my novel-writing classes about the publishing business. Many students are seniors getting ready to graduate. Hence, they are full of anxieties. The first thing they say is: Why didn’t anyone teach us about this sooner!

This is what I tell them.

Relax. Nobody told me about any of this when I was an undergraduate. And very little of it when I was in graduate school, something I’ve discussed already here.

The reason that undergraduate creative writing instruction is not focused on publishing is very simple: very few of you are ready for it right now. In my experience, a writing apprenticeship is about 5-10 years long. The timer starts the day you start taking writing seriously—meaning you stop thinking of writing as homework and start incorporating it into your daily life.

So, if very few of you are ready for it right now, why am I talking about it at all? Simple: because when you are ready, I won’t have time to explain this to you.

At least once a week, I get an email or message from someone I barely know who says, “I have written a book. How do I get it published?” I hate these messages. It’s like someone emailing a lawyer and saying, “I have decided to represent myself in a courtroom. Will you explain the legal profession to me now?”

“Publishing” isn’t something you can explain to anyone in an email, in 60 minutes or less, or in a blog post (although this one comes close!). And it’s not the responsibility of your teachers to explain it all to you, to “teach you how to publish.” They are responsible for teaching you to write well. Nothing matters more than that. The presentations I give don’t teach you how to publish so much as they teach you how to begin thinking about it.

Why didn’t I talk about this sooner? My God, does your generation need even more reasons to obsess about the degree to which you “matter?”

You say things to me like: “I just want to publish a book and hold it in my hand.” Are you sure that’s all you want? Because these days, you can publish a book and hold it in your hands fairly easily. What I’m trying to talk about are all the different ways to publish. Only you can decide what it means to you to be meaningfully published.

Often, when you say “I just want to be published,” what you mean is that you need the external validation of publishing. You need to be able to show others—your friends and family and your hometown enemies and your ex-partners—that you “made it.” This is a horrible reason to publish, and if publishing is all about proving something, then I predict you will rush things and make a mistake you’ll regret. And that you’ll have a nervous breakdown and/or become an alcoholic.

You say things to me like: “I need to find a job that relates to writing.” When I ask you why, you say, “Because I want to be a writer.” This is when I realize that you don’t know very much about how writers become writers. You don’t “become” a writer because of a particular degree or a particular kind of job, although, yes, being attached to a company or a school makes one feel legitimate more so than, say, selling cars or working in a law office or nannying or house painting or working as a geologist—which are all things that writers I know do (or have done) to pay the bills.

Let me emphasize this: the job you get after graduation has nothing to do with whether or not you are a writer.

Let me emphasize this: applying to (and being accepted into) a graduate writing program has nothing to do whether or not you are a writer.

You say things to me like: “But I just want to know if I can be a writer.” And I want to say: First of all, why are you asking me? Nobody—no degree-granting institution, no teacher, no editor, no association—grants you the status of writer. You don’t need anyone’s permission to be a writer. You have to give yourself permission. It’s an almost completely internal “switch” that you have to turn on and (this is harder) keep on.

You say things to me like: “Show me how to succeed, how to build my platform, how to get an agent,” and I want to say, “That is what I’ve been doing.” Because I’ve been teaching you to write well. All you control are the words on the page. Everything else is a crap shoot. Whether your work is ever published, where it gets published, if the book is reviewed, if anyone reads it or likes it, how your publisher will decide to represent and market it, what they put on the cover—none of that is in your control. The only thing you can do is sit down every day and give it your best. Some days resemble slow torture, but others will bring joy, what the writer Andre Dubus called “the occasional rush of excitement that empties oneself, so that the self is for minutes or longer in harmony with eternal astonishments and visions of truth.”

You say things to me like “How do I know if I am a writer?” and I want you to watch the end of the other Capote movie, Infamous. Harper Lee’s character says:

It’s true for writers too who hope to create something lasting. They die a little getting it right. And then the book comes out. And there’s a dinner, maybe they give you a prize and then comes the inevitable and very American question: ‘What’s next?’ But the next thing can be so hard because now you know what it demands.

I’m 43 years old, and I thought that publishing a book meant I was a writer, but I was wrong. Convincing yourself each day to keep going, this means that you are a writer. The world will be sure to declare, “You matter, but you don’t. Wow, your work is exciting, but yours is old fashioned and dull.” What do you do when someone says, “Eh, you’re okay, I guess.” Do you stop? Or do you keep going? That’s the moment when you know whether or not you’re a writer.

You say things to me like, “Will you be disappointed in me if I stop writing,” and I want to say, “No, of course not.” Coming to terms with whether or not you are a writer might take years, which will surely drive everyone who loves you crazy. Try to avoid this, if possible. If you keep going, you’re a writer. If you decide to stop, simply tell yourself, “Well, I guess that was something I needed to do,” and move on as peacefully as you can.

Don’t be a writer because you have something to prove. Don’t do it because you think writers are celebrities. They are not celebrities. Don’t do it because you think it will bring you a happy life. I’m sorry, but it won’t. You shouldn’t write because you want to create something lasting, although that probably surprises you, doesn’t it? What better reason could there be? I’ve only found one good reason to sit on your ass for four months or four years, one good reason to give so much of yourself for so little in return, one good reason to create something that fewer and fewer people care about—and that’s simply because you want to.

You ask me, “Am I writer?” and I say, “There’s only one way to find out. Write the book. And see what happens.”

April 3, 2012

How to talk about a WIP

There's no crying in 292 Robert Bell.

To my novel-writing classes,

Next week, you'll meet with your small group and talk about 25-50 pages of your WIP (work-in-progress), the novels you've been working on this term. This is the moment when a lot of novels fizzle out, but it's also the moment when a lot of novels get a much-needed vote of confidence.

My book, The Circus in Winter, got that kind of boost back in 1993. I describe that workshop in full here.

Forty-five minutes of productive discussion, and I walked out with pages of scribbled notes, stories crystallizing in my brain, and boom, I was off.

I was lucky.

Typically, students want to prescribe. They want to talk about what's not working. It's up to the instructor to create the default setting, to frame the workshop so that big things can be brought to the table and discussed meaningfully.

That, my friends, is what I'm trying to do here: change the default setting, frame our small group discussions so that everyone walks out the door elated, not deflated.

In order to change the default setting, I've purposely placed you in groups of Potentially Sympathetic Readers. The people who like fantasy are reading each other's stuff. The young women writing about relationships, they're reading each other's stuff. The sci-fi folks are reading each other's stuff. Does it matter if the sci-fi folks would hate the novels about relationships, or vice versa? Not one little bit.

This week I asked you to share you fears about showing your partial to others. I've cut and pasted some of your comments, and provided my responses.

What you're worried about

"I'm worried about whether my story is good or not."

It's impossible to say whether a novel is "good" at this stage of the game. Readers might like the premise, the character, the idea, but there is no "good" or "bad" at this point. There are only possibilities.

"I have no qualms about showing my work in progress. The worst thing that can happen is you all hate it, right?"

Actually, you aren't allowed to "hate" each other's manuscripts. It's too early to decide if you hate anything. The only reason you might is based on subject matter or genre, which is why I placed you in groups of Potentially Sympathetic Readers!

"I feel like what I'm sharing with my group is the equivalent of the first scene/section of a short story."

This is a wonderful analogy. It's like being in a poetry workshop and getting the first stanza of a poem-in-progress. Or being in a fiction workshop and getting the first page or two of a short story…dot dot dot.

Typical Workshop Response: You're mad at the writer for submitting something unfinished. What are you supposed to say? She didn't even finish the darn story/poem! What a lazy bum! So you go off a little. The writer, who can't say anything, takes her lumps, collects her critiques, and scurries out of the room.

Small Group Response: You say, "Given what's going on in this stanza/scene, here are three questions I have that I hope you will answer in this poem/story." And the writer, who gets to speak, says, "Yeah, I'm going to do number 1 an 2, but where did you get the idea for number 3. I didn't realize I was even talking about that…" etc.

For people who write as scenes come to them

"I wrote a lot of good scenes I think. It's just being able to string them all together that is throwing me off."

If your manuscript is comprised of scenes without all the "connective tissue," simply tell your small group this. Include a prefatory note at the top of the manuscript, or include a note between two scenes that says, "I need something to connect the last scene to this one. Any suggestions?"

Then the group can't say to you, You have a lot of good scenes, but they don't fit together. Because you have already admitted this. Thus: pointing out this flaw is no longer the point. The point is: how might they be strung together?

"I switched what I was writing at week 4, so I'm not entirely sure how much material I have to work with. I'm hoping that I have enough and I don't have to use completely new material to make it to 25 pages. I think I have about 7 right now."

I don't know why this writer thinks he has just 7 pages, because I know I've read more than that each week. Maybe the writer has the first 7 pages and then various chunks from elsewhere in the book. Not necessarily sequential pages. This is fine. As long as we get something of an introduction or preface, you can submit non-sequential pages, as long as you make sure you tell your group that you're doing that, and you make sure that by the time of the final, you've got the first 25-50 pages nailed down as best you can.

"I'm confused about what to include. We polish writing from the beginning of the novel, format it, and email it, but what if the writing that we have doesn't follow a particular order? I have scenes from different areas of the novel that's and now I have an ending, but they're all rough drafts and scattered on a word document."

Like I said above: it's okay to show us disparate pieces as long as you try to have some kind of opening, and as long as you preface your manuscript with a note to the readers explaining that they are NOT reading sequential chapters.

"I think my biggest worry so far is the structure. I'm still unsure of how I want to break the novel up into chapters or sections, so I'm hoping for some feedback on that."

Best way for a reader to help this writer is to say, "This what it was like for me to read this manuscript the way it's currently structured," and then describe it.

For people who are writing a less-than-perfect "down" draft that they will fix "up" later

"I know the writing and language isn't fancy – I haven't taken the time to make it such, so I know that needs work. What I would really like to know is if my ideas are going in the right direction. Can you see this turning into something bigger and better with more work?"

To do a micro-editing job on this person's manuscript would be a huge mistake. What this person wants and needs is some encouragement. To tell him that no, you can't see this being a book would be—in my opinion—quite cruel. I've been teaching creative writing for 20 years, and I've read a lot of work, and I have never once said "No, this isn't a good idea. Don't tell this story." It is not up to you or me to decide that for someone. It's up to the writers themselves. There are those who DO think it's their job to discourage writers, but I am not that person, and I don't want you to be that person either.

I've had students who sat in my office and BEGGED me to tell them whether they had "it" or not, and I said, "It's not up to me to tell you that. You have to figure that out for yourself."

For the masochists

"Often, I feel paranoid when people read something I do and don't tell me what I did wrong, as it makes me feel like they are being too nice. By all means, rip my novel to shreds, if need be!"

Nobody's ripping anybody's anything. Readers, you're not supposed to be "too positive" nor "too negative." You're supposed to be somewhere in the middle. How the writer interprets that approach is up to him.

"I'm looking for very critical feedback, the kind of stuff that you wouldn't say to your closest friend. I'm not worried about feelings and pride, only honesty."

I say it again: IT IS TOO SOON TO BE "HONEST" OR "HARSH" or "BRUTAL" WITH PEOPLE ABOUT THEIR NOVELS. I know that some of you are saying, "Rip me to shreds," but what I'm saying is, according to all my research and experience, that is not the way a novel workshop works, esp. novels that have barely gotten started.

Note: If ever I am in a position to offer this course as a two-semester sequence, then I would step up the level of critique in the second class.

For the fragile

"I'm terrified."

"I'm not sure if I ever want to share my work publicly."

"I think it will be nice to have someone other than my good friends read it because I will get some writer's advice instead of friendly advice. I need to know what to change, what works and what doesn't."

Readers, imagine that your job as a reader is to be both a writer AND a friend to the writer.

"I don't typically share things that I am in the process of writing, except with a few select people. People I went to school with didn't have the best attitudes toward my desire to write, and as a result I don't tend to trust anyone with my writing. A professor is one thing – something I have become comfortable with – but students I've never met, never spoken to, and couldn't pick out of a line-up is a totally different matter – something I am very uncomfortable with. If given the choice, I wouldn't be sharing a partial with people I don't know."

Please know that the number one consideration I made when placing you in groups was that you'd get a sympathetic reading from that group of people. If I was wrong in how I made my selections, please let me know.

"I think that the feedback I will receive on it will greatly help me decide exactly what I want to do with the novel."

This is a very good attitude to take.

"Since this is such a massive undertaking, I want someone to tell me what I need to change early on before it becomes to overwhelming to change."

Ditto this.

For those who are writing pages that are summaries or synopses of their novel, not real pages.

"My biggest worry about my story is that I am writing it in a compressed format. I know this can easily be changed through revision and expansion, but for me I feel it is easier to just get the story "down on paper" before worrying about expanding and lengthening."

It's vital that you explain to your group what you are giving them! And if you're the person reading this kind of manuscript, it's vital that you be able to picture what they are synopsizing. Imagine that you are trying to decide if you want to watch a movie, and you read the synopsis of the plot off of IMDB or Wikipedia.

For those who say they just don't care

"I guess what it really comes down to is that I'm really pretty detached from my work. It's still personal, and I still take pride in it, and I still get my feelings hurt a little when people say bad things about my writing, but I'm not totally emotionally invested in the work."

A little detachment goes a long, long way. But don't feel too detached!

Remember that this class is about process, not product

Remember: we are not "workshopping" your WIP.

The kind of "workshopping" you'll be doing in your small group is fundamentally different. I talk about the difference between a typical workshop and a novel workshop here.

In the typical workshop:

You assume that you're looking at a whole piece that has a beginning, middle, and end.

You read and "mark up" the manuscript on the sentence-level.

You assume that the manuscript is a "problem" and your job as the reader is to "fix" it.

But in a novel-writing group:

You're not looking at a whole piece.

You're looking at something on the macro level, not the micro.

Your job is not to fix the manuscript.

To be honest, the manuscripts you're going to read will have many, many problems. So what? The whole point of writing a novel is that you have to flounder around quite a bit. So how can you fault someone for floundering? And how can you say, "Give it up, man," when they've barely gotten started?

In sum

Writers: Tell your readers how you need them to read what you're giving them. It's important to tell them in the manuscript itself, and during the discussion.

Readers: Tell the writer what they want to know, and aim for a critical, but generous frame of mind.

March 22, 2012

Novels vs. Stories in MFA Programs Survey Results

My plan was to release the survey results one question at a time via ruminative blog posts like this one on whether MFA programs are "anti-novel" or not and this one on the "professionalization" question.

My plan was to release the survey results one question at a time via ruminative blog posts like this one on whether MFA programs are "anti-novel" or not and this one on the "professionalization" question.

But I've changed my mind. Many people wrote to me privately and said, I want to see the results! I'm curious!

Also, I'm going to be under the weather for the next few weeks.

So: here are the results of my Novel in MFA Programs survey.

Tell me what you find interesting, surprising in these results, and when I'm back to my desk, I'll talk about it!

March 18, 2012

Should we make it our business to teach the business of being a writer?

Here's the question I asked both MFA faculty and students on the survey.

MFA programs should avoid "professionalization" and "business" issues related to the writing life, such as discussions of the market and what sells.

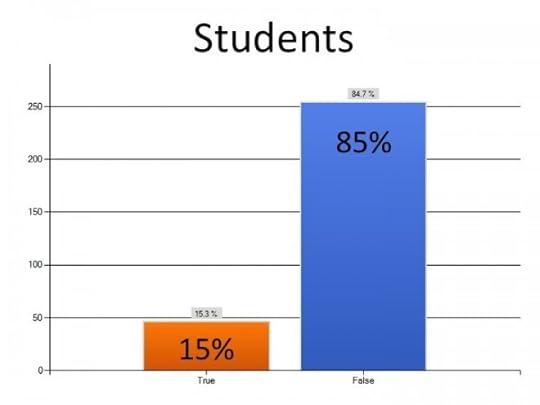

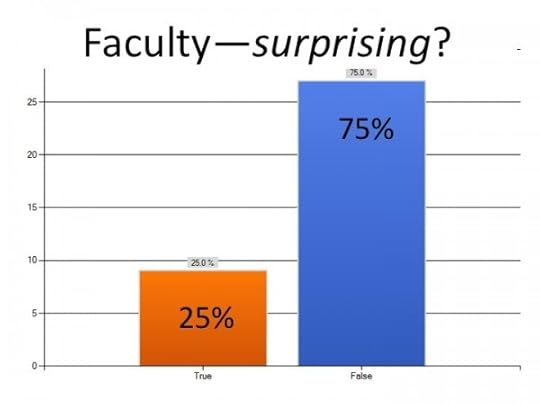

And here are the results:

No surprise there!

I was kind of blown away by how many faculty said false.

This might surprise you: I selected TRUE. Let me explain that. And let's talk about what we mean by "professionalization."

Which business are we preparing them for: academia or publishing?

I was trying to make a distinction between:

academic professionalization of grad students (creating a CV, how to apply for academic positions, how to give a "job talk")

non-academic professionalization (creating a resume, how to write a query letter, synopsis, or book proposal, how to enter the publishing world).

The former activity almost always happens in English departments, especially those with PhD programs. In my MFA program, the creative writers prepared themselves for the job market by going to meetings for PhD students on "How to enter the profession via the academic job search." We creative writers translated for our own purposes (dissertation = book manuscript, etc.) and sought additional assistance from the CW faculty and writer friends a few years ahead of us. I got very little MFA-specific guidance in how to pursue academic employment, but I did get something, even if it was pitched to PhD's, not creative writers.

The latter activity, non-academic professionalization, which we'll call "How to get published," or "What to do next," sometimes happens in MFA programs, but not often in classes, per se. You're more likely to find it happening in the co-curriculum (delivered via panels, visiting writers series, info sessions) or in one-on-one sessions between thesis advisee and adviser.

I got my MFA long ago in 1995, and back then, my program didn't explicitly address any of these things:

how to submit work to magazines

how to find an agent

how to pitch a nonfiction story to a national magazine

how to do a book proposal

how to apply for grants and fellowships

how going to writers' conferences might help me find new writing peers and possible blurbers

And I definitely didn't learn anything about how to build and maintain a website or online presence. (It was 1995. We were barely using email then.)

These days, I do talk about these things explicitly–at the end of my advanced undergraduate and graduate courses. If you check out the syllabus of my novel-writing class, you'll see that I teach them how to write a pitch, query, and synopsis. I show them how to format a book manuscript. I show them how to submit to literary magazines and how to learn from rejection.

Dangling the Carrot

If you encourage someone to embark on a big thing, dangle a carrot in front of them so they'll finish it. I tell my students, "If you keep writing this book and revise it and make it as perfect as you can, send it to me and I'll see what I can do to help you." A few weeks ago, one of my former undergrads got an agent who is going out with the novel my student started in my Senior Seminar. In this case, I was able to help a student directly, although most of the time, my help is more indirect, more like pointing former students in the right directions or encouraging them not to give up.

If you encourage someone to embark on a big thing, dangle a carrot in front of them so they'll finish it. I tell my students, "If you keep writing this book and revise it and make it as perfect as you can, send it to me and I'll see what I can do to help you." A few weeks ago, one of my former undergrads got an agent who is going out with the novel my student started in my Senior Seminar. In this case, I was able to help a student directly, although most of the time, my help is more indirect, more like pointing former students in the right directions or encouraging them not to give up.

Why do so many apprentice writers give up writing? I think it's because they don't know what to do next. They don't know what to do with the books we encourage them to write. They think publishing is a secret society, and they aren't the right sort, they won't get in. I say bullshit. I say read this. I say let's give them some agency, and I don't mean a literary agent.

But I need to tell you this: I'm enormously conflicted about the fact that I do these things.

If writing is a business, should we teach marketing?

Some people think that MFA programs should help students build an online presence. Last year in the Chronicle, Brian Croxall advised PhD students to do this:

…you want to start now in building an online profile so that you'll like what they find. You can start by Googling yourself to see what information is out there already. Then work to grab your own space on the web, whether it's a blog, wiki, static website, or space on Twitter (or all four). In these spaces you should keep your updated CV, materials related to courses you've taught, first drafts of your work, or anything else to help colleagues and potential employers understand your research, teaching, and skill profiles. As guest ProfHacker and friend Dave Parry wrote in a post on academic branding, you want your profile to "demonstrate to the world what type of scholar you are, and what you do." I personally recommend using your real name, as it will establish your online foothold that much more strongly.

Do we really want to teach MFA fiction candidates how to create a website, how to understand the market they're writing for, how to brand themselves? Do most MFA faculty even understand what that means?

Just thinking about this issue makes me itchy–because it's a complete anathema to the way I became a writer, and yet, I know it's incredibly important these days to be an "author-preneur."

I work now with the Midwest Writers Workshop, a great conference in Muncie, Indiana. Last year, I was on the faculty and over a two-day period, I taught short sessions on craft, but because I was scheduled against sessions on HOW TO GET AN AGENT and HOW TO GET A MILLION TWITTER FOLLOWERS (I'm exaggerating a little), I spoke to a very small number of people. To address this problem, this summer, we created an entire block of nothing but craft sessions to emphasize how much the conferences values good writing AND learning the business.

The point is: Faced with the choice between an opportunity to learn how to be a successful, popular writer vs. an opportunity to learn how to be good, highly skilled writer, most people will choose the former. Do MFA programs really want to present even more opportunities for young writers to obsess about SEO or their Klout score?

If writing is a business, should we teach them how to stay in business?

But on the other hand (can you tell how conflicted I am about this subject?!) given the state of the academic job market, how can we not offer some real-world survival skills to the hundreds of students we loose upon the world each year?

This is a very serious question.

And isn't this at least part of the reason to offer instruction to fiction writers in how to write a novel?

And while we're at it, how about teaching them how to adapt the novel into a screenplay or teleplay, as writers like Benjamin Percy and Dean Bakopoulos and many others have done?

In a Huffington Post article last year, Brian Joseph Davis suggested "diversifying with more commercial applications of creative writing," which would "balance practical skills with the no less important art of completely impractical, clever and beautifully unmarketable literary fiction writing."

In a Huffington Post article last year, Brian Joseph Davis suggested "diversifying with more commercial applications of creative writing," which would "balance practical skills with the no less important art of completely impractical, clever and beautifully unmarketable literary fiction writing."

I'd suggest including screenwriting, as some programs already do, or adding more new media courses. How about courses that prepare MFA grads for ghostwriting an unauthorized Hugh Laurie biography, one that earns them enough money to pay rent for a year so they can work on a novel?

As a former MFA faculty member, I'm interested in anything that gives MFA students an opportunity to lead literary lives–however they choose to lead them. At the same time, I want to pose this question: Isn't it hard enough to teach someone to read and write well in 2 or 3 years? Are MFA programs responsible for equipping graduates for all possible professional outcomes?

I don't know the answer to this question, mind you.

This will make me sound like a fuddy duddy, but I have to say it: as mentioned above, my MFA program didn't professionalize me about the publishing world, and yet, here I am anyway. Everything I thought "being a writer" would mean in 1995 is completely different today, and I've adjusted.

It's not that I think my students should "learn things the hard way" just because I did. Rather, I think the way is always hard, no matter what you do or how you prepare someone.

Meaningful anecdote

Once, I was on a committee charged with reading alumni surveys. All undergrad English majors. One guy wrote to say he was very disappointed in his major because at his first high school teaching job, he was asked to teach The Sun Also Rises, "and you never made me read that book!" To which we responded, "Did you read any Hemingway? Did you read any Lost Generation writers? Did we teach you how to read a book critically, how to research things you don't already know? Surely we did. Surely we can't prepare you for the exact circumstance each graduate will face. We hope we taught you the most important thing: how to teach yourself."

If writing is a business, so is creative writing instruction

In the years ahead, MFA programs must decide whether or not to respond to these demands for more professionalization, more real-world, practical skills. Because they will start losing students: to the Grub Street Novel Incubator, to low-res programs, to courses (IRL and online) offered by independent centers and literary magazines and the distance-education arms of major universities, to the growing number of writer conferences, to privately run writing groups, to critique sessions offered by writers.

As creative-writing instruction goes, MFA programs used to be the only game in town. Now, they aren't. If a young writer knows exactly what she wants and an MFA program can't provide that, she will look elsewhere for those opportunities–and believe me, she will find someone ready to give her exactly what she wants.

What about you? What do you think? I'd really like to know, because as you can tell, I'm awfully conflicted on this issue. I'd also like to expand these thoughts and publish them. What other topics should I explore?

March 15, 2012

How I Answered the AWP Survey

What if this person wasn't talking about "being a writer," but rather about "being a teacher of creative writing"?

Take the survey! You have until March 22. It's important. I filled it out the other day, and I found that I had so much to say in that little comment module I decided to cut and paste it into a document and share it with you. FYI: I also provided my email address on the survey, so I didn't say all this stuff to them anonymously.

[Question 21. We welcome any additional comments, feedback, and suggestions you would like to share with us through this survey or at conference@awpwriter.org.]

–YOU HAVE TO BOOK THIS CONFERENCE IN A SPACE THAT PROVIDES *FREE* WIRELESS INTERNET IN BOTH THE HOTEL ROOMS AND IN THE CONFERENCE PANEL ROOMS, BOOK FAIR, ETC. Seriously. You just have to. (I organized my panel thinking that the audience would have access to the web. They did not. And this sort of blows my mind a little.)

–Cancelling the Pedagogy Forum had the unfortunate result of putting some apprentice teachers who don't have much to say yet in huge, largely empty ballrooms. Apprentice teachers need to meet and learn from other apprentice teachers. How can we better assist MFA students who are trying to professionalize themselves as teachers?

–The best panels I went to were comprised of people who'd prepared something to say, but kept it short enough so that a conversation could follow. I understand why AWP directs panelists NOT to prepare and read long papers, but I'd rather have that than off-the-cuff banter. I come to learn, not be entertained. I'm pleased to say that all the panels I went to were well-organized, and all but one was thoroughly engaging.

–Once upon a time, the acronym AWP stood for ASSOCIATION OF WRITING PROGRAMS, but at some point (I can't find the year this happened), this was changed to include ASSOCIATION OF WRITERS AND WRITING PROGRAMS. This signaled an important (and positive) shift in the AWP's focus and overall reach. While I'm REALLY happy that the independent publishing scene has a strong presence at the Book Fair, and I'm REALLY happy we offer top-notch, marquee-quality readings to the public, I often feel that the old "W" and "P" in AWP (WRITING PROGRAMS) gets short shrift in all the hoopla. Let me explain.

–AWP is the governing body of, the professional meeting of WRITERS IN ACADEMIA. I come to AWP in large part to recharge my batteries and engage with others in my profession. I go to other kinds of conferences and events to engage with writers in general. At AWP, I find that the panels devoted to pedagogy, program administrations, and other professionalization issues of importance to me are sparsely attended. This is not your fault, but by opening the door to WRITERS in general, which is a good thing, we also remove a lot of focus from the fact that WE ARE AN ACADEMIC DISCIPLINE.

–Seemingly, we want one foot in academia and one foot out, and there are benefits to this stance, but also some negative consequences, too. To ameliorate those consequences, I suggest choosing two keynote speakers—a headliner, one who isn't in academia (like Margaret Atwood) who can speak to the W=Writers crowd, and an opening act, one who IS in academia, who is publishing well AND teaches well AND who is or has run a program (like Charles Baxter, Michael Byers, Richard Bausch, Porter Shreve, Jesse Lee Kercheval, Lan Samantha Change, Sven Birkerts, Robin Hemley, A. Manette Ansay) who could speak to the WP=Writing Program crowd. You might say that the winner of the George Garrett Prize is this person, but that award is for "Community Service," not for being a professional academic writer-teacher with things to say about that profession. If you're worried that an address to the WP crowd will "alienate" the W crowd, I say, too bad. I truly believe that our discipline cannot gain better traction within academia unless we try harder to "discipline-ize" ourselves. The risk, yes, is that we become that which we hate, but we have chosen to ensconce ourselves in academia, and academia seems to be waiting for us to decide: Are we in, or are we out? How we orchestrate our conference demonstrates that commitment (or lack thereof).

–I believe in AWP. This conference, which I've been attending since 1998, has helped me grow as a writer and as a college professor. Thank you.

[Did you go to AWP? You should take the survey, too!]