Cathy Day's Blog, page 16

April 25, 2011

Kim Barnes: Learn the Craft, Trust the Process

Recently, a former student emailed to say he'd been accepted into a few MFA programs, but ultimately, he'd decided on the University of Idaho. When I asked him what made the difference, he cited the beauty of the location, the full funding. "And," he said, "Kim Barnes has created a multi-semester novel workshop, and I think it sounds fantastic."

Recently, a former student emailed to say he'd been accepted into a few MFA programs, but ultimately, he'd decided on the University of Idaho. When I asked him what made the difference, he cited the beauty of the location, the full funding. "And," he said, "Kim Barnes has created a multi-semester novel workshop, and I think it sounds fantastic."

I knew this was one person I definitely needed to talk to. So I emailed her out of the blue and asked her if she would mind sharing this experience with the readers of my blog. She was kind enough to say yes.

Okay, first things first: describe this multi-semester approach. What are the logistics?

As I teach it (and other instructors do it differently), the Novel Workshop is open only to candidates for the MFA in Fiction, with preference given to second- and third-year students. Enrollment is limited to six, is by application only, and is competitive. I require that each interested student submit a letter of application/intent and a 1-2 pages synopsis of the proposed novel project (which we all understand will almost certainly change during the course of the workshop).

Our discussions and meetings actually begin at the end of the current spring semester, when I meet the six students who have been accepted into the class to talk about the protocol, process, and content of the course. We also begin preparations for a summer reading class by discussing the students' proposals and contemporary novels that might prove informative.

Over the summer, the students read and respond to the same six-to-eight novels, and those responses are shared with the entire class, resulting in an ongoing discussion of craft and techniques that carries through the coming academic year.

Once the formal academic year begins, the workshop meets once a week for three hours, and it is a two-semester workshop. The students are required to present the first 150 sequential pages of their novel about halfway through the first (fall) semester and the second 150 pages toward the end of the second semester. Ideally, by the end of the year-long workshop, they have a working draft of a novel.

That's a good idea: You give them the summer before to get those first 150 pages ready. What happens during each semester?

The first half of the workshop each semester is taken up with discussion of craft, and, more importantly, visits from established novelists. We are lucky to be rich with novelists in our area, and even more fortunate that many of them are willing to come and speak with the workshop for little more than a bed and a meal. The published authors spend the entire class time with the students in a very informal setting, answering questions about everything from revision to how to end a story to effective writing habits to the inevitable cycle of depression/elation/depression/elation. It is an intimate discussion and often continues at a local bar. Past and future visiting novelists include Claire Davis, Anthony Doerr, Jess Walter, Kevin Canty, Debra Magpie Earling, Sam Ligon, and Brady Udall.

What else is unique about your approach?

I involve the students in my own writing process. I share with them my new ideas, old drafts and edits, send them copies of my email correspondence with my agent and editor, show them reviews of my novels, good, bad, and ugly, and generally make myself vulnerable, open, and available. I tell them about my fears and confusions and how I make my decisions (both good and bad) about characters, plot—you name it.

That's an amazing idea: you basically create a writing group with your students. What are the advantages of giving your students such "behind the scenes" access?

I remember that, in the first workshop, I was finishing work on my second novel and had a disagreement with my editor over a scene that happened to be my darling. I resisted changing it and told the class so. They wanted to know how writers make those kinds of decisions—when to listen to the editor, when to refuse in the name of "artistic integrity." "You have to draw a line," I told them, and this is my line. This is the sword I will fall on." I laugh now because, of course, I was taking a prideful stand. My editor was able to articulate why the scene needed to be changed in such a way that made me see that she was right, and I had to put my sword away. What is important here is that the students were a part of the discussion and were able to witness my resistance, indecision, and decision first-hand.

I think it's incredibly rare for writer-teachers to bring their students inside in this way. Why do you think that is?

I think that, all too often, as writing instructors, we try and keep distance between our lives as writers and our students' lives as writers. But mentoring isn't only about craft—it's much more complex than that. It's saying, this is how I stay in the room and persevere. These are my fears and uncertainties. There is no magic here, only dedication to the craft, discipline, and stubborn resolve.

I think this is a great idea. Writing programs should teach students how to professionalize themselves, and what better way than for practicing writer-teachers to make their own professional lives transparent to their students.

I like to talk about the business of writing. It should never be confused with the art of writing, but I never shy away from the realities of the business. We discuss query letters, synopses, finding an agent, small press versus New York publishing houses…everything and anything that has to do with the writing life. I email the students' questions to my agent and editor, and they send back short answers. We talk about networking, making connections, writing conferences, how to balance making a living with making a novel…I call it a full-immersion class, and it is.

Okay, so for the first half of the semester class time is given over to the visits by novelists. Then what happens?

The second half of the semester is spent in formal workshop. The first willing student hands out his/her 150 page manuscript two weeks before the first formal workshop so that readers have at least two weeks to read and compose written comments. (Students are required to provide copies of their comments, which often run 10-20 pages, to the author and to me.)

The workshop discussion focuses on observation, process, and possibility–on craft–and what revisions might be considered to bring the story into its most integrated, unified, and ideal form. It is essential that the group works together, is critical but supportive, and offers not only observation of strengths and weaknesses but possible approaches to revision. Simple response and observation is never enough. My goal is to have the student writer leave the workshop with a set of concrete approaches that he/she can consider and possibly apply. The student writer should never leave the workshop feeling lost and disheartened. Frustrated, yes, but confident in the process. My mantra: learn the craft; trust the process.

What inspired you to create this course?

Like you, I have always felt that MFA programs struggle to find ways to support and implement a novel workshop–it is such a baggy monster of a class, but how can we not teach it? I have an absolute conviction (more so since developing the novel workshop) that teaching the novel is really nothing at all like teaching the short story. The novel is not simply an elongated short story–it is a different animal altogether.

When, four years ago, several MFA candidates in fiction came to me to ask that I lead a directed study in writing the novel, I said, no (too much time–really, I couldn't imagine). I encouraged them to talk with our department chair about formally offering the class, and to our surprise, he agreed.

People don't understand that running such a small course costs a department a lot of money and can be difficult to staff; you have to have room in your teaching schedule to commit to this class for a year. Your department is clearly very supportive of students who want to write novels.

I feel very fortunate that we have the support of our department and administration because the class requires a great deal of time and resources yet enrolls only six students each semester. It is a privilege, really, to offer it, and I think it speaks very well of our university's willingness to be innovative and entrepreneurial. The class had garnered quite a bit of attention; in fact, one of the reasons award-winning novelists are willing to visit the class for a thin slice of their usual honorarium is because they are interested in and eager to see how the class works, and some are interested in attempting a novel workshop at their own universities. What I most appreciate about these visiting writers, however, is their desire to mentor and bring the student novelists into the circle of shared writing experience.

[Dear reader who wants to try this, Kim Barnes has just given you the talking points you can use to persuade your own department. No, it won't be easy. But have you ever REALLY tried?]

What would you say to that fictional colleague who comes up to you at the copy machine and says, "Just six students! That's easy. You must get tons of writing done."

Outside of the published novels, articles, and secondary texts that we read, the student work alone—novel drafts, revisions, and critical responses—often comes in at over 1500 pages a semester. A one-semester class is considered three credits, but the workload per semester easily equals that of a six-credit course, which is one of the reasons I hesitate to teach the novel workshop. I find it exhilarating but also exhausting, as do the students. You have to mean it and really commit to the process.

Tell me about the results. Did the students finish their novels?

My goal in teaching this class is similar to the old adage about fishing: Give a man a fish, he eats for a day; teach a man to fish, and he eats for a lifetime. I don't expect the students to have finished a novel by the end of the year, only to have attempted a working draft of a novel. Where possible, I want the process of the class to mimic the process of the real writing life. We all know that writing and publishing a novel can take years—and maybe a lifetime. I think of Ron Carlson's short story mantra–just stay in the room. In his wonderful book Ron Carlson Writes a Story, he takes us through his process of writing a particular story, which he drafted in a single day. But to write a novel, you have to stay in the room for, well, sometimes thousands of days. I also quote Carlson when he says that the only advantage a seasoned writer has over a beginning writer is the ability to withstand the "not knowing." This is what I want to teach: craft, process…and perseverance.

That's the hard part, isn't it? You can't know how long it will take you to figure out your novel. Coordinating that learning process with a bunch of other people during a finite amount of time—well, it's complicated, I'm sure.

I taught the first novel workshop in 2007-2008. Unlike this years' incoming class, none of the students came with a draft in-hand—and I kept reminding them that first drafts are always flawed. It's the nature of the process. All of the students found that their first 150 pages would require extensive revision. One of those students realized his main character probably wasn't his main character. Another struggled with back story, another point-of-view, another pacing. The majority of the story arcs weren't yet arcs at all but fragments of arcs. In other words, the dilemmas they faced were the dilemmas that most every novelist faces at some point in the process.

And this presented me with a problem I hadn't wholly foreseen: If the first 150 pages aren't yet working enough to support the next 150 pages, do I still require that the students write and submit the second half of the novel the next semester? I ended up making the decision on a case-by-case basis, which also corresponds to real-life writing scenarios: as novelists, how often do we have to make the same decision to stop and revise or move forward and then go back and revise? If the novel's story line was not sufficiently developed but was, nonetheless, clear and firm, I instructed them to move forward. If the story line still wasn't clear and whole-scale revision was required, I suggested working on the revision second semester rather than moving forward. What happened was that the students who revised did so quickly and were able to turn-in at least some part of the next 150 pages as well as an outline of the remaining pages, so, in that way, the structure of the class remained successful.

But here is the thing: the workshop remains an academic exercise. There is no perfect formula, and any approach necessitates compromise and flexibility. In the "real" world, every writer has a different process: some start at the end; some write spatially or in fragments that they then flesh out; some, like Jo Ann Beard or my colleague Daniel Orozco, seem to never set a word to page that they haven't considered in their heads for months or even years; I most often write like I'm building a house: I pour the foundation, nail together the frame, wire and plumb, put up drywall…until, by the last revision, I'm situating the furniture and hanging pictures on the walls.

Yes, I've been using the "building a house" method for my own project, and I show that process to students, but let them work in a variety of ways, as you describe, which is as it should be, I think.

The process is, by necessity, arbitrary. I always say it's like taking a Pilates class: I force you to conform, to work certain muscles, to strengthen the core. What you do with that discipline and strength once you leave the class? That is completely and delightfully up to you.

In so many ways, the workshop is a microcosm of the writing process. I remember being at a party in Missoula with the great writer James Welch and sitting down beside him because he seemed uncharacteristically quiet and glum. When I asked him how he was doing, he shook his head. "I've got it all wrong," he said, "the point-of-view is all wrong, and point-of-view is everything." He had just come to the realization that the 300-plus pages he had been working on for years would have to be completely revised, and, because he was already a critically-acclaimed novelist, he knew just how long the process would take: another year, at least, and maybe more.

I share these anecdotes with my students, and I tell them about my own trials and tribulations: When I gave my first novel manuscript to my writing group (we've been meeting for over twenty years), they said, "We don't know who your main character is, and we don't know what this story is about." Gaaah! I was disappointed, of course—despondent, really—but I simply had to go back to work. The answer to the problem is always at the level of craft. I changed the point of view, which helped me identify the main character, and I began to begin again. As writers, that is what we do.

We talk about "revision" in fiction workshops, but revising a short story isn't like revising a novel. It's just not.

No, because as novelists, our scale is larger in every way: number of pages, number of hours in the chair. I've written short-form—poems, essays, and short stories—and I have never felt despondent. With short-form, the process of revision feels so comparatively manageable. I know short story writers who work on the same story for years, polishing and honing, but what is different is that you can keep those ten or twenty pages in your head—literally see them by laying them out on the floor. When I'm working on a short piece, I can go to bed at night and scroll through those pages in my mind's eye. But four hundred pages that you discover aren't working? I'm just sayin'…it's different.

Oh, I totally agree.

So when the students become frightened and frustrated by the process of revising a novel, I'm right there with them—simpatico. "You can do this," I say, "because I have been there and survived." The big issue is this: Do you want it bad enough to persevere? This class will teach you that, if nothing else.

Tell me about the students who took that first class. What happened to them and their novels?

That first class of six became very tight-knit, and we still stay in touch and send out group emails and updates. Most of those six writers continue to work on the drafts of their novels; some have received positive responses from their queries to agents; some have had excerpts from their novels published. Some of them have set the novel aside to focus on short stories or on essays but plan to revisit and revise. One of the former students recently mentioned that she wasn't interested in her main character anymore, which is another aspect of this process to consider: the novel that you draft when you're a twenty-three-year-old MFA candidate may not to be the novel you're interested in when you're twenty-seven and working for Teach for America in Mississippi. Another one of the students, who continues to work diligently on his novel, recently wrote to say, "Tell the new students to beware of the minor character who will rise up and take over the story."

That first class is now a part of the ongoing (email) discussion that takes place outside of the workshop, and those first students are there to mentor the new students, which is another aspect of the novel class that I am intent on—creating and sustaining a community that can function as resource and as a network of support. I've laughingly said that the novel workshop is a kind of self-help group, but I'm somewhat serious. We always say that writing is a lonely endeavor, something you do in solitude while, simultaneously hoping that your words will reach a multitude. We all know how isolating it can become, how impossible the endeavor can feel, how improbable it can seem that you'll ever realize your goal of finishing and publishing the book…and this brings me back to my earlier assertion that, finally, my most absolute instruction is this: learn the craft; trust the process.

Thank you, Kim Barnes, for sharing this with my readers. Your students are very fortunate. I'm glad that my student, Brian Scullion, will be joining you in the fall. And you, reading this, stay tuned for guest posts from some of Kim's students.

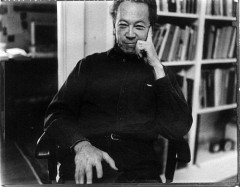

Kim Barnes is the author of two memoirs and two novels, most recently A Country Called Home, winner of the 2009 PEN Center USA Literary Award for Fiction and named a best book of 2008 by The Washington Post, The Kansas City Star, and The Oregonian. She is a recipient of the PEN/Jerard Award for an emerging woman writer of nonfiction. Her first memoir, In the Wilderness, was nominated for the 1997 Pulitzer Prize. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in a number of journals and anthologies, including The New York Times, MORE, O Magazine, Fourth Genre, The Georgia Review, Shenandoah, and the Pushcart Prize anthology. Her next novel, In the Kingdom of Men, an exploration of Americans living in the Aramco compounds of 1960s Saudi Arabia, is forthcoming from Knopf in 2012.

April 18, 2011

The Swamp

When I was a little girl–reading novel after novel, watching movie after movie–I noticed one thing: men got to retreat from the hubbub of family life into their own special rooms, and that their time in this room was sacrosanct. They were not to be disturbed unless it was an emergency. This truth cut across time and class. I saw no difference between the way that Mr. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice retreated to his study

and the way that my father retreated to The Swamp, his garage/man cave/beer fridge/smoking area, the place where he has always gone to get away and think and process and fiddle with things.

A writer friend of mine told me this story about his mother, who is an author of many novels and the mother of four children. She always wrote at a table that was situated in the middle of the room where he and his sisters played. Her writing sessions were often interrupted–fetching this or that, moderating this argument or that, fixing this meal or that–but the writing got done.

My mom didn't have a Swamp either. No physical space that was just hers. No room of her own. My mom read and sewed and cross stitched in the middle of the chaos that is Real Life. She learned how to disappear into her head, how to give herself some Swamp Time, while still being physically present.

From a very early age, I understood (without really understanding) that what I needed in life was lots and lots of Swamp Time. As a child, I ached for solitude. I wanted to be left alone so I could "spend time in my head," a kind of dissociative state that allowed me to blessedly not be me for short periods of time. I realize now that this dreamy activity was an early form of my writing practice, that I have always been a writer, even before I started writing things down.

But Swamp Time created a great deal of friction in my life. Sometimes, my retreat (whether it be a physical retreat to another room or a mental retreat to another world) made others wonder What's wrong? Did I say something to upset her? Why doesn't she want to play? Why does she have to set herself apart like that? Doesn't she like me? Why is she off in La-La Land when I'm sitting right here talking to her?

I came to understand (without really understanding, a kind of instinctual knowing) that women don't get swamps. Either they get called out of The Swamp upon entering, or they feel selfish about needing Swamp Time in the first place.

[I don't want to argue about this. Maybe you're a man who knows exactly what I'm talking about here. That's fine. I'm just saying this is what a very young Cathy Day intuited about the world she lived in, which was incredibly gender stratified.]

I want to start being more direct with my students about this kind of thing. I need to say: If you want to be a writer, you need to find and protect your Swamp Time. Know that life isn't going to just give you this time. You have to do all the work yourself—fiercely, rigidly. Stake your claim to your Swamp. Find the space–physical or mental space. Find the time, whether it's in big chunks or in small bits. You must be absolutely fearless and a more than a little selfish about this, which for some people (like me) is hard.

Caveat: In his "Letter to a Young Writer," Richard Bausch says, "Train yourself to be able to work anywhere." Remember that writing is not an excuse to neglect the people in our lives who count on us. "It is an absurdity to put writing before the life you have to lead. I'm not talking about leisure. I'm talking about the responsibility you have to the people you love and who love you back. No arduousness in the craft or arts should ever occupy one second of the time you're supposed to be spending that way. It has never been a question of the one or the other and writers who say it is are lying to themselves or providing an excuse for bad behavior. They think of writing as a pretext for it. It has never been anything of the sort."

I also need to say to my students: You need to date and marry someone who understands this notion of Swamp Time.

Writer-teacher Julianna Baggott has a great series on her blog called "A ½ Dozen." She sends six questions to fellow writers, and one of those questions is always this one, and man oh man, do I wish that someone had told me to think about this when I was younger: "What's your advice to a writer who's looking for a lifelong partner? Any particularly useful traits to suggest in said partner?"

Writer-teacher Michelle Herman had this to say:

My husband is as absorbed with his own work as I am with mine (he is painter), and he too had never been married. He worked all the time, and he needed to be left alone…He thought it was perfectly natural for me to lock myself up in my study for eight or ten hours at a stretch, and he didn't try to talk to me before I had my morning coffee. These were for me dealbreakers. If this doesn't sound like a love story, so be it—but we've been living together for nineteen years, mostly in harmony.

For the last few weeks, an essay's been making the rounds called "How to Steal Like an Artist and Nine Other Things Nobody Told Me." Artist Austin Kleon dispenses some truly great advice, and number 9 is "Be boring. It's the only way to get work done." He advises artists to get over the clichéd notion of the hard-living artist and learn to live simply and well. Be healthy. Stay out of debt. Work a day job to pay the bills. Make sure you punch in every day for some Swamp Time.

And then this: "Marry well. It's the most important decision you'll ever make. And marry well doesn't just mean your life partner — it also means who you do business with, who you befriend, who you choose to be around."

Maybe it seems absolutely ridiculous to you. Creative writing teachers offering relationship advice! Time management advice! Family and relationship dynamic advice! How absurd!

But any writer with at least ten years' seniority and a book or two under the belt will tell you that writing well is about more than craft. It's also about the way you choose to live your life.

April 10, 2011

Shall We Play a Game?

Greetings Professor Falken

For the last few days, I've been trying to come up with a way to "gamify" my novel writing process. To give each day's writing session a strategic goal. A certain number of pages, or words, or time spent. During October and November 2010, my goal was 850 new words a day–every day–and this period of sustained productivity was deeply satisfying. In a short period of time, I drafted an extremely rough 175 pages of my novel.

My progress lately, however, has been more difficult to measure, to quantify. Every day, I edit and shape the those pages I generated in the fall. Every day, I feel as though I've gained a little a little more insight into my character, into the book's themes, and how the book will be shaped. But strangely, these achievements towards quality feel less satisfying to me than when I was focused strictly on quantity. So I decided to go back and reflect on this post, written during that period of high productivity.

Confession: For twenty years, my writing practice had no structure. I wrote when inspired and I would keep writing until I wasn't inspired. If I didn't have a big block of time, I wouldn't write. I waited until I did have a big block of time–which happened…oh…never. For a long time, I acted (without really realizing it) as if writing was something I did "for school."

And then I started meeting working writers. By "working writers," please note that I'm not saying anything about literary quality or relative success, only that they were "working," or writing regularly, regardless of whether they were publishing well, or even at all. Asked privately (over a beer, in a conference) to talk about their writing process, most working writers would confess that they were regular and ordinary in their habits, like Flaubert. Working writers, it seemed to me, had one thing in common: they had figured out a way to tap into the motivational aspects of their character. If there are any "secret" to having a writing life, this is certainly one of them.

Perhaps the reason NaNoWriMo has found such a following is that it encourages writers to turn an abstract big thing into a series of small concrete things. Words. Pages. Accumulating incrementally over time. Like racking up points in a video game.

Perhaps this is why NaNoWriMo is so popular with Generation Y: because it turns writing a novel into a game. A huge, dynamic multi-player game in which you accumulate words and pages instead of points.

Perhaps creative writing teachers should teach not just the craft of writing–which is basically the evaluation of what students have already written–but also the act of writing itself.

Perhaps writing a novel is a game–one you play against yourself, mostly. The only way to win is to get a first draft, and you do it bird by bird, page by page, racking up words until you have finished the draft.

Perhaps what has always separated "real writers" from "wanna-be writers" was that real writers figured out some way to get the writing done. More than likely, this involved creating some kind of internal rewards system or "gamification" to tap into the motivational part of their brains. And then they crafted, yes, and they used their talents and intellects, yes, but first, they had to write a draft.

Perhaps one of the reasons why we have more "real" writers in our culture, more books, is that we have more ways to create (or to pay someone else to create) the necessary reinforcement, and thus, more people who embark upon and finish books.

That's a lot of perhaps-ing, I know. But I have a novel to write. Strike that. I have a three pages to write so that I can reward myself tonight with the PBS premiere of the revamped Upstairs, Downstairs.

April 3, 2011

No Word Allowed

A few months ago, I gave my Intro to Creative Writing class this assignment:

Create a story, essay, poem, or play that is composed in anything EXCEPT Microsoft Word (or any word processing program). You must type the text into some other kind of software or application or tool, such as Google Maps, Facebook, Flickr, Xtranormal, Power Point, Ebay, Survey Monkey, Blogger, etc. Basically: if it's got a dialog box you can type in, then you can use it. Your piece must engage with, make use of the medium or mode you've selected.

At first they thought I was crazy, but I spent some time showing them examples:

Like Jennifer Egan's "Power Point story" from A Visit from the Goon Squad.

First slide of story

Like Dinty Moore's Google Maps essay about George Plimpton.

Like Patrick Madden's Ebay story about Michael Martone's water bottle.

Like this "Facebook Story" covered and edited by the Washington Post.

Like Rick Moody's Twitter story published by Electric Literature.

Students: So you want us to write a story and tweet it?

Me: No, that is exactly what I don't want you to do. I want you to compose something in Twitter, for that storytelling platform that takes into account the way we read and experience Twitter. I want you to compose something in PowerPoint that takes into account the way we read and experience PowerPoint. Recently, Jennifer Egan had this to say about how she wrote her story in PowerPoint:

EW: What was your process of writing the Power Point chapter?

JE: Well, I took a crack at writing it on yellow legal pads, by hand, which is how I write most of my fiction, but that was basically a nonstarter…I bumbled quite a bit at first, just trying to figure out how to use PowerPoint and avail myself of its features. I finally settled on a methodology something like this: I'd pinpoint the fictional moment I wanted to portray (PowerPoint only allows for the creation of moments, without connective tissue). Then I'd list what seemed to me the essential component parts of that moment as a series of bullet points. Then I would study those bullet points and try to understand their relationship to each other: was it cause-and-effect? Was it circular? Was it a counterpoint? An evolution? Having identified the relationship of the parts to each other, I would choose (or, when I really got comfortable, create) a graphic structure to house the bullet points that would clearly manifest their relationship. There were lots of revisions and reconsiderations, of course, but that was how I did it, slide by slide.

Students: Like how the Twitter story is told in a series of epigrams? And you can almost read it either up or down?

Me: Precisely. Or you could do it this way and create a Twitter Murder Mystery, like this Ball State student.

Students: What else can we do?

Me: You can dramatize a scene, put on your own puppet show, with Xtranormal.

Students: So you want us to fool around on Xtranormal?

Me: Sort of, yes. I want you to write something that takes advantage of its capabilities and builds those capabilities into the story. You can also write a poem presented in Power Point. What does Power Point do? It gives you information one bit, one slide, at a time, forcing you to slow down—a perfect medium for the poetic line. Power point also allows you to link between slides and add sound effects and images—a perfect medium for a simple Choose Your Own Adventure story.

[Contemplative silence.]

Students: We don't know what you want.

Me: Okay, okay, open up your laptops and type in http://www.chromeexperiments.com/arcadefire/

[Everyone is riveted by this interactive film, watching themselves virtually run around their own personal "Wilderness Downtown."]

Me: Okay, now watch this one.

[Classroom yawns.]

Me: How did you feel when you saw your childhood house? Your neighbor's house? Those places you know so well? You probably felt many emotions. Have you ever taken someone you love to see the house you grew up in and felt like you could never explain why that place matters to you so much.

Students: [vigorous nodding]

Me: How did you feel when you saw someone else's "Wilderness," like the one on YouTube?

Students: Nothing much.

Me: Right, because that's what storytelling is–taking those images, those feelings inside you and putting them inside someone one else, using nothing but language.

Students: Oh. Yeah. Wow.

Me: So, here's Google Maps. Show me your "Wilderness." Tell me about it. Take advantage of the fact that I can zoom in on Street View and see whatever you want to show me. Tell me a story.

[There were so many great ones, but this was my favorite.]

Students: Is that fiction or nonfiction?

Me: That's nonfiction.

Students: What if we want to write fiction in Google Maps or Power Point?

Me: When composing digitally, remember this acronym: MAPS. Media + Audience + Purpose + Situation (rhetorical context). For example, Egan's power point story has an invented rhetorical context in that it's "narrated" by her character Alison Blake. It says so on the first slide. That's how we know it's fiction.

Students: Why are you making us write this way?

Me: Because this is the way we will tell stories. Because this is how you're already telling stories. Every day.

March 27, 2011

"No Writing is Ever Wasted" by Lowry Pei

I've "met" some extremely cool people since starting this blog, such as writer-teacher Lowry Pei. He's the author of the novel Family Resemblances, as well as many short stories, essays, and book reviews. He teaches writing at Simmons College, and he blogs about teaching writing at On the Way to Writing.

NO WRITING IS EVER WASTED

by Lowry Pei

A bold statement, I know. I make it with a crucial condition attached: No writing is ever wasted, as long as you keep writing.

In 1975 I decided that since I had written a 300-page dissertation for my Ph.D., thereby proving I could make something of that size, I would try to make something I really wanted to write: a novel. Of course, after years of higher education in which I focused on novels as much of the time as I could (my dissertation was on Anthony Trollope), I immediately found I had no idea how to write one. So I set out to try anyway.

I did what I now think is the usual thing novices have to do: I had no idea how to create a story out of whole cloth, so I started writing a narrative that was part of my not terribly exciting life with the names changed. After most of a year, I had "finished" this cringe-inducing piece of work and showed it to a T.A. of mine, Kim Stanley Robinson, who has since become a deservedly celebrated science-fiction author. "Pei," he said, "where's the fiction in this fiction?"

Busted. Well, what could I do? I started over. This time I attempted to tart up my life experience by adding some things my own life didn't have much of (action, sex), thinking, I guess, that if I sprinkled these fictitious jimmies on the autobiographical sundae, it would pass for what it wasn't.

Of course that didn't work either. Then a very kind person (Kathryn Marshall, the author of My Sister Gone) read this crappy manuscript and said I should try writing it in the first person. That, in the end, opened the door and led me actually to begin writing fiction; so five or six years after I first started trying, I finally completed something I could truly call a novel.

It wasn't very good.

But all that writing wasn't wasted because I finally knew what the hell I was doing. The next novel I wrote was Family Resemblances, which got published by Random House and thereby legitimized me as "a novelist." I got all excited and wrote another novel; I sent it off to Random House and they promptly rejected it. A colleague of mine, the poet Bill Corbett, read it and said, "It didn't come as a story." He was right; it was more of a Chautauqua than a series of dramatic actions.

But all that writing wasn't wasted; for one thing, it was apparently what I had to write, and I had to get it written in order to keep on writing. Meanwhile, it was teaching me more and more about writing. The narrative shifted among several viewpoint characters, which was a technical challenge I hadn't taken on before. Though as a novel it was too much of a talk-fest with meditative counterpoint, that made it also a major lesson in crafting dialogue and interior monologue. And that wasn't the last novel I wrote that didn't work; later I wrote about half a book starring Karen, the protagonist of Family Resemblances (and its sequel, From the Next Room), that didn't work. It started to feel forced and then it lost its forward momentum and died a natural death. In a word, so what? Was it such a bad thing to have discovered, through writing, that that story didn't have to be told? I didn't think so then and I don't now. If anything, I think that effort taught me a major lesson about letting go. Writing can be very hard and require a large capacity for persistence, not to say stubbornness, but along with the stubbornness you have to learn when to let go. Just because you can write your way down a certain path as a writer, that doesn't mean you should. And though writing stuff that doesn't work is not a waste, it's possible to lessen the amount of time you have to spend learning the hard way.

I first learned that in the writing of Family Resemblances. Late in the first draft, near the end of the book, I was writing in a way typical of me, not knowing (and not wanting to know) what was coming next or how the book was going to end. There was a fork in the road of the story and I chose which way to go and started off in that direction. I was writing the same as before, I was well inside the world of the story as I had been for a long time, I could imagine every particular of the scene as it unfolded with no diminution of its reality. I obviously could write this. But the more I wrote my way down that road, the more I felt a nameless, unignorable sensation in my stomach. Its location felt very specific. It wasn't a sharp pain or even an ache, but there was something ineffably wrong about it and it wasn't going away, it was slowly getting worse. After perhaps twenty pages of this experience, I decided my stomach was trying to tell me something specific: This thing you're writing right now? It's not the thing you need to write. Don't go this way. It will only take you farther and farther from where you want to go.

That was good advice. The tricky thing is that you have to learn when to trust it. You have to learn how to sort out the many passing somatic experiences that go on in the background of writing, the twinges of anxiety and dread, the fits of discouragement or euphoria, and figure out when the faint, fleeting, but definite feeling that something is not right means that something is not right. The only way to learn that is to act on the feeling and see what happens. When you discover that yes, it really wasn't right, that that message was trustworthy, you have a brand-new powerful tool. As long as you keep writing. Otherwise, it's as if somebody gave you a gorgeous new table saw but you never built anything with it.

The most powerful confirmation that no writing is ever wasted came about twenty years after I first started trying to write a novel.

After writing my apprentice novel that didn't work – or perhaps simultaneous with it, I can't remember for certain – I wrote many drafts of a long story which I thought wanted to be a novella (it was eventually published as "Vital Signs" in 1987). That story's protagonist is an insurance agent named Tom, living in Columbia, Missouri. His wife is pregnant and he is possibly falling in love with his temporary secretary, though we never do find out what comes of that. He is definitely having some kind of existential crisis. Tom is descended from the protagonist of the apprentice novel, who also lived in Columbia, Missouri, and also worked at a mundane job, behind the counter of his camera shop. So that novel that didn't work gave rise to "Vital Signs," but my imagination wasn't done yet. The fourth novel I wrote was about an insurance agent living in Columbia having, this time, an unmistakably spiritual crisis that became a strange journey into a shamanic underworld, a sojourn on the borderline between ordinary reality and another that's equally real and totally at odds with the everyday. It was, I realized about halfway in, the novel I had been trying to write all along, even in the very first effort that didn't work, the one I wrote in order to learn the basics of craft. So that initial impulse was far more powerful than I ever realized, and all that work had started something bigger than I ever imagined.

So much for writing being wasted. And this experience brings me to something I find strange and wonderful: it is possible to start to imagine, and start to write, a story that one is absolutely unable to complete at the time – a story that will only finally be written years later, when one has been through enough life experience, has written enough, read enough, matured enough, evolved enough to be the person who can at last write it. When you start that story not only can you not imagine where it will eventually go, you cannot imagine the person or the writer you will eventually become. But you will, and it will.

If you keep writing.

– Lowry Pei, March 2011

Lowry's thoughtful comments on my posts have deepened my thinking about this subject, and apparently, the feeling's been mutual. A few months ago, he started his own teaching blog, On the Way to Writing, "resources and meditations on writing and teaching writing."

Here is his invitation.

After thirty-plus years of writing (fiction, especially novels, and non-fiction), teaching writing, directing writing programs, and working with teachers, I want to share my ideas and materials with whoever can benefit from them.

Basically, this incredible writer-teacher has opened up his file cabinet to us. You'd be crazy not to take Lowry up on this generous offer. Spend some time on his blog. You'll be glad you did. There you'll find essays like this one.

March 20, 2011

Memo: Course Descriptions are due for Fall 2011

Are you ready to get serious about leading a Big Thing writing class? I know I am. Here's my plan for my Advanced Fiction Writing course during Fall 2011.

Course Description

In this class, all students will be required to produce at least 50,000 original words, the first draft of a new work. This will not be done only during November's "National Novel Writing Month," but rather over the course of the entire semester. The course will be characterized by: intense focus on the writing process and on developing a writing regimen; weekly word count check ins; "studio" in-class writing time; practice in creating an outline or storyboard of a book; small peer groups for feedback; and analysis of a few contemporary novels that will serve as models.

Course Objectives

This semester, you will teach yourself how to write a novel. The manuscript you produce may be the first draft of a novel you will someday publish. Or it may be what many writers refer to as their "apprenticeship" novel, their "drawer novel."

Course Rationale

In "The Habit of Writing," Andre Dubus describes two types of writing—horizontal and vertical. For example, a short story might be composed horizontally—draft after draft—over the course of a month, or it might be composed vertically—one perfect sentence at a time—over the course of a month. Many of us write vertically because we've mostly composed stories and papers on short deadlines, and word processing allows us to edit as we write.

Principle #1: We will operate on the assumption that novels, as opposed to short stories, might need to be composed horizontally, that the fictional skill set we have acquired thus far is insufficient to meet the demands of novel writing.

Writing horizontally often means that what's on the page is messy, incomplete, not the kind of writing we'd submit to an instructor to be graded, to a workshop for peer critique, and certainly not to an editor to be published. But that's okay because:

Principle #2: We are not writing a novel so much as we are drafting a novel, which means that we are not overly concerned with the quality of the writing, but rather with the quantity.

Of his "failed" novel Fountain City, Michael Chabon has said, "Often when I sat down to work, I would feel a cold hand take hold of something inside my belly and refuse to let go. It was the Hand of Dread. I ought to have heeded its grasp." So: how do we learn to distinguish the difference between "The Hand of Dread" (which would indicate that our project indeed should be abandoned) and "Normal Dread" (the fear and anxiety we're confronted with every time we sit down to write)? When do we ignore the dread, and when do we listen to it?

THE HAND OF DREAD!

Principle #3: You do not have to finish the novel you start writing this semester, but before putting it aside, you must think seriously about whether the problem is that the project is flawed or that you have reached the end of your ability to meet its challenges.

If that principle terrifies you, good. Writing a novel is a daunting task, but I also want to maximize your chances of success. In order to do this, I have drastically revised the way I teach fiction writing. This course will not provide you with a customary experience, and if you're aren't okay with that, please don't take the class.

Principle #4: We will operate on the assumption that no one is here reluctantly. You're here of your own volition. You want to learn. Perhaps because you love to read novels and want to better appreciate their composition and execution. Perhaps because you've "always wanted to write a novel." Or because you have tried unsuccessfully to do so in private.

Methods of Evaluating Student Performance

Note: We have approximately 15 weeks. 50,000 words/ 15 weeks = 3,333 words a week or about 476 words a day. (To give you some perspective, the above section, "Course Rationale," is 481 words.)

300 points or 30%: Weekly Word Counts. Every time you make your weekly quota, you get 20 points. If you fail to meet your quota, you don't get 20 points. 15 x 20 points = 300 points

200 points or 20%: Book Report Project. You will choose a book from which you need to learn something, devise a method to learn that something, and write an analysis that demonstrates what you learned. You will turn in not just the paper, but also physical evidence of your grappling.

200 points or 20%: Your Storyboard. You will be required to create a blueprint for the book you want to write. It can be as complete or incomplete as you need it to be.

200 points or 20%: Participation. There will be no Big Group Workshop. Instead, you will work in Small Groups, which will meet in class and online. For the first few weeks, we'll rotate around so that everyone can see what each other is working on, and then you'll select your Small Group for the remainder of the semester.

100 points or 10%: Final. At the end of the semester, you will polish a 10-40 page writing sample and learn how to write a "pitch letter" summarizing your work in progress.

Possible Texts

Inspiration Book: Chris Baty's No Plot, No Problem or Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird

Practical Book: Writer's Digest Books, The Complete Handbook Of Novel Writing: Everything You Need to Know About Creating & Selling Your Work

Realism/coming-of-age books: Stephen Chbosky, The Perks of Being a Wallflower or Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok

Suspense/"I couldn't put it down" books: Emma Donoghue's Room or Thomas Harris' Silence of the Lambs

Genre/Sci-fi/dystopic books: Kevin Brockmeier's The Brief History of the Dead or Suzanne Collins' Hunger Games or Justin Cronin's The Passage

Plot as a given books: Paula McClain's The Paris Wife (based on the life of Hadley and Ernest Hemingway) or Irina Reyn's What Happened to Anna K (modern retelling of Anna Karenina).

These books will serve as our models. I've organized them in this way, labeling their "type," not because I'm encouraging you to embrace marketing categories, but rather because experience has taught me this: you stand the best chance of finishing a novel if 1.) you consciously choose to write the kind of book you yourself enjoy reading, and 2.) you do not set yourself up to fail by choosing as your model something akin to Faulkner's Absalom! Absalom! (which happens to be one of my favorite books). I'm not discouraging you from having literary or intellectual ambitions, but rather (again), I'm trying to maximize your chances of meeting the goal of drafting a novel—in this case by encouraging you to create reasonable expectations for yourself. Also, you will receive a long list of books on the CRAFT of novels upon completing the course.

In this class, everybody wins

There is no such thing as a "failed" novel—as long as we keep writing. Next week, we'll hear from writer-teacher Lowry Pei, who will address that very subject in a guest blog post: "No Writing is Ever Wasted."

March 13, 2011

You're Not Ready to Write a Novel: by Rebecca Rasmussen

If you would like to write a guest post for "The Big Thing," by all means, let me know. Maybe we could trade? That's what debut novelist Rebecca Rasmussen and I did. My essay on "Literary Citizenship" appeared on her blog, The Bird Sisters. I'm really looking forward to her book, which will burst into flight on April 12.

You're Not Ready to Write a Novel

By Rebecca Rasmussen

You're not ready to write a novel. If you can't write a proper short story, what makes you think you can handle the scope of a novel? Why would you want to write a novel, when short stories are the far superior art form? Stick with what you know. Haven't you heard of Poe's unity of effect?

It seems unbelievable to me now that anyone was ever not in support of me writing a novel, but after attending two MFA programs, I have to say that the above statements are generally what a student of fiction can expect to hear over the course of their time in a writing program. The question now that I have written a novel that's being published in April is why?

My general feeling is that a lot of professors who teach in MFA programs write short stories (often because that's what they were taught to write) and therefore teach short stories. Some love novels, others don't. I think it's safe to say that in a lot of programs novels get a bad rap because people are so busy defending the merits and the superiority (artistically) of the short story. Not that they don't love novels; they just don't love them in a workshop.

But why?

First, the basics. I think the committees that decide which classes will be taught often don't know how to approach a class on novel writing in terms of workload and description. Will the students be writing a chapter? A whole manuscript? Either option doesn't seem to win many over, including the professors that will be teaching the courses for two reasons: 1.) A single opening chapter doesn't aptly teach students how to write a novel, and 2.) A whole manuscript from twelve or so students is a workload that is too large and would send said professors very far away from their own writing projects that semester, which I sympathize with completely.

In my first MFA program, no one said, "Don't write a novel," but no one said, "Give a novel a try" either. Experiment. Probably my writing was so unkempt at that time that reading the shorter version of it was grueling enough, so I am thankful that such care was taken with my work back then by my hardworking professors. And it didn't seem a completely obvious thing to do—to write a novel—when most of what I was reading was short stories. A novel? What was that? You mean like Dostoevsky? I think I studied that guy in college.

When I was in my second MFA program at UMASS-Amherst, the faculty there managed to reach an interesting and workable balance. (Also, I was older and more mature by then.) One of my professors, Sabina Murray, taught a novel writing class, where we were expected to produce or come into the class with 150 pages of a novel. Each week, we workshopped one student's novel-in-progress. The class was capped at ten students. I learned a great deal about novel writing by reading the first halves of other novels and by writing my own (and making my own mistakes—many, many mistakes). I learned that I was trying to stuff my novel full of plot because that's what I thought I was supposed to do. I learned that my first chapter confused people and even made some angry. Yikes! Not my intention.

What I value about that experience even though I didn't end up finishing that novel is that I was no longer afraid to deal with a never-ending manuscript and that I actually enjoyed the mess of a first draft much more than the constraints I put on myself as a short story writer (including that obnoxious little self-imposed epiphany to round out the arc of the story). I have published a handful of short stories in wonderful literary journals, but this isn't the form that is most natural to my storytelling.

I love thinking about plot and character on a larger more layered scale than what I am personally capable of achieving in a short story, but don't get me wrong: some of my very favorite writers are short story writers. Alice Munro, Alan Heathcock, and Siobhan Fallon. I admire these folks very much, and maybe one day I will be in the right frame of mind to write short stories again. For now, though, I am sticking with the novel even though it goes against 90+% of my training. And at some point, I would love to teach a novel workshop because I think it's simply not accurate to say that a writer isn't ready to write a novel if he or she can't write a short story. Who can really say such a thing? Who has the right? Leap, is what I say.

Though many people disagreed with her, Sabina also said three very practical things in her novel workshop that stuck with me:

1.) You need a book, often with a major press, to get a job in an MFA program these days.

2.) Major New York presses generally veer away from short stories.

3.) How much do you like teaching freshman composition?

I'm not going to tell you that I started writing a novel for purely practical reasons because I didn't. (I fell in love with the form after writing 150 bad pages, if you can believe it!) But at the time I had just given birth to my daughter and our dismal financial situation was on my mind. I may have fallen into the trap of saying these dangerously potent words: "If only I can sell a novel…"

It turns out that being broke is excellent motivation for writing and finishing a novel, for continuing when the going is rough and it looks like no one wants it, and for knocking on doors until someone says yes. For revising and revising and revising. The way I figure, writing a first novel is a lot like writing a first short story: there is a lot of muddling through to be done, a lot of failing, and maybe, if a writer is really lucky, a little success to be had.

Rebecca Rasmussen is the author of the novel The Bird Sisters, forthcoming from Crown Publishers on April 12th, 2011. She lives in St. Louis with her husband and daughter and loves to bake pies. Visit Rebecca at http://www.thebirdsisters.com for more information.

March 9, 2011

The Big Thing in Film School & Fiction School

Here's part 2 of my interview with Alexander Georgakis, a young filmmaker fresh out of film school, who has lots of smart things to say about making art in and out of school. Read part 1 here.

A lot of people say that young writers are not "ready" for novels, that they must learn from shorts. What do you think about this?

I definitely think young filmmakers should attempt to make short films before diving into features. But, in terms of comparing young filmmakers and young novelists, again the subject of cost must be addressed. A young writer can draft a novel, and if she wasn't "ready" to actually tackle a novel, she can keep revising it, or put it aside completely and value her effort as a learning experience. For a young filmmaker, if he attempts to make a feature, and he isn't "ready," he could waste an enormous amount of money, whether his own or someone else's. (Most do-it-yourself features have budgets in the six-figure range–though sometimes within the five-figure range–while most of what we consider "independent" films today have budgets in the millions.)

Screenwriters, like novelists, do not have to worry about the "cost" of their efforts. I do think learning to write short scripts is a good place for beginning screenwriters to start–it can be easier to focus on specific elements of craft like pacing and dialogue within a fifteen page script as opposed to a one-hundred and ten page feature. But I also think a large part of being "ready" to produce any kind of creative work involves living life–you can spend your whole life studying the craft of writing or filmmaking but if you don't spend time actually experiencing the world you probably won't have anything interesting to write or make a film about. Ultimately, though, the only person who can truly determine whether you're "ready" to create a short story/novel/film/etc. is yourself.

A lot of people feel that creative writing programs only prepare students to write short stories, which are not as marketable as novels. Do you think film schools do the same with short films? Is this as big a topic in your world as it is in mine?

Yes to the first question, no to the second. In other words, in my opinion, film schools do not prepare students to make feature films. However, most debates about the effectiveness of film school focus on other topics.

For instance, many are less concerned about whether film schools prepare their students to make features–and more concerned about whether film schools even prepare their students to work on features, in any capacity. Many argue that film schools can provide a strong foundation for a career, but struggle to teach students the skill sets that will actually prepare them for the entry-level jobs available to them in the entertainment industry (i.e. production assistant, executive assistant, etc.) upon graduation.

There is also much sturm und drang at numerous film school programs in which only a handful of students are selected to direct the highest-level films in the program. Once again, COST rears its ugly head: many film schools do not have the money to fund thesis films for sixty students, or however many might be in each class. So the schools select, say, four students to direct those films, and the rest of the class pays the same amount of tuition to work in crew positions on those films. Luckily, for creative writing programs, you do not have to worry about choosing four students who will get to write a "big thing," while the rest of their classmates provide feedback, check spelling and grammar, and provide illustrations!

There is certainly a lot of (healthy) debate about how film schools should or should not prepare students for work in the entertainment business. However, because the vast majority of film school students will not begin directing features immediately upon graduation (and, in fact, statistically, most film school students will never direct a feature at all), there is not as much concern about the fact that film schools do not prepare students for features, at least compared to the level of concern may seem to have regarding creative writing programs and novels.

Thank you so much to Alexander for answering my questions, and for bringing my story, "The Lone Star Cowboy" to life.

Alexander Georgakis grew up in Santa Barbara, CA, and moved to Los Angeles to attend the University of Southern California's School of Cinematic Arts. As a student, he majored in Critical Studies, and served as the director for USC's 1st Annual Independence Film Festival and the 3rd Annual LA-wide Crosstown Film Festival. Upon graduation, he received USC's prestigious University Trustees Award. In addition to pursuing his passion for film, Alexander has also enjoyed working as a musician throughout Los Angeles. He served as the conductor/accompanist for the Los Angeles premiere of The Life with Jaxx Theatricals, and past credits include positions as the music director for Theatrical Arts International's productions of The Music Man and The Pirates of Penzance, and the accompanist for The Theatre @ Boston Court's new musical, Gulls.

March 6, 2011

The Short Film is to Film School what the Short Story is to Fiction School

After my essay came out in The Millions, I started wondering: does the problem of accommodating short vs. long forms extend into other disciplines and art forms? Do film schools, for example, use short films as their primary pedagogical tool just as creative writing programs use the short story?

I emailed Alexander Georgakis, a young filmmaker I know, and asked him this and other questions. In 2010, he adapted my short story, The Lone Star Cowboy, into a short film, and I knew he'd recently graduated from film school.

[image error]

In film school, do you focus on the short feature before embarking on the feature-length film?

Absolutely. Film school programs teach students how to make short films.

What analogies can you draw between the instructional models I talk about in the Millions essay and your own experience of being a film student? I mean: You do narrative, and so do creative writers. There are many similarities, it seems to me.

Most film schools have a class called "Writing the Feature Screenplay," or some such equivalent. In the majority of these types of classes, students will outline their ideas for features they would like to write, receiving input from their classmates in a round-robin setting that seems fairly similar to that of your creative writing courses. The students will then embark on actually writing their screenplays, and at the end of the semester will turn in the first thirty pages of their scripts as the final assignment for this course. (Most full-length feature scripts come in at around 100-120 pages, averaging a page of text per minute of screen time, so this final assignment compromises about a quarter or more of a feature screenplay.)

Essentially, having film students complete thirty pages of a script in a class entitled "Writing the Feature Screenplay" is the same as having creative writing students write thirty pages of a story in a class called "Writing the Novel." The course has ensured that students will know how to get a "big thing" started, but it leaves the students to finish these big things on their own. These types of classes seem most analogous to those you discuss in your essay.

On the other hand, many film schools have advanced level writing classes in which students revise feature-length screenplays they have already completed prior to the commencement of that semester. This may be one area in which film programs do differ from creative writing programs. Because it generally takes less time to write a feature screenplay than a novel, many film school students will be able to complete drafts of multiple feature screenplays before they graduate, whereas it does not seem common for creative writing students to draft numerous novels before receiving their degrees. In this way, teaching screenwriting may simply be a more manageable feat than teaching novel writing, even if learning how to write a good screenplay may not be any easier than learning how to write a good novel.

On the production side, film schools prepare students to make short films. Period. While there may be some exceptions, I have to imagine that most film schools would fairly strongly discourage (if not flat-out forbid) their students from attempting feature length projects in place of the short film assignments that make up their curricula. (In some of my classes, our short film assignments even had maximum time limits, and our grades would suffer if we let our projects run too long.) This perhaps parallels your scenario in which the Curriculum Committee refuses to allow stories to run longer than 15 pages, though I think film schools have very solid reasons ($$$$$$$$$$$$$$) for imposing these limitations on their students. (I'll elaborate further on this subject in upcoming answers!)

Is there a difference between graduate and undergraduate film programs in terms of the size of projects you're assigned? or is it uniformly "shorts" all the way through?

There is not much difference between graduate and undergraduate film programs–both focus uniformly on short filmmaking. I actually strongly considered returning to graduate school last fall, but I decided against it for a number of reasons. Many people who I admire and respect in the entertainment industry encouraged me not to return to school, suggesting that I had already had the film school experience, and that continuing to work in the industry would teach me more than essentially repeating my undergraduate education.

This strikes me as a major difference between your world and mine. It seems to me that creative writers are encouraged to study their craft academically as undergraduates, and then advised to continue those studies in graduate school. In the entertainment industry, I haven't come across too many people who would recommend that young filmmakers obtain multiple film school degrees. I've had numerous bosses who did not even attend college at all, much less film school.

What did you learn from adapting a short story (mine!) into a short film? How did this prepare you for feature-length?

Still from "The Lone Star Cowboy"

What I learned most from this project was how to make a film outside of school. I learned a ton about fundraising and budgeting, as I had never before made a film on this level budget. I learned a great deal about location agreements and permits, because I had never had to secure private locations for a film shoot. I learned about insurance, which I had never much thought about before, because film schools all have their own insurance. I learned how to negotiate prices on equipment rentals, which I had not done before, because film school had always provided me with equipment. And I learned about Screen Actors Guild contracts and agreements, because I became a SAG signatory producer on this film so that I could hire union actors.

Admittedly, I made some mistakes while learning about these aspects of filmmaking, and there are certain situations (both creative and logistical) that I would handle differently if I had the opportunity to go back and experience them again. And yet, I am glad I made certain mistakes while making this short, because I know I will definitely not repeat these errors when I ultimately make a feature.

In terms of what I learned specifically from adapting a short story, I would say that my admiration for screenwriters who adapt previously existing material grew exponentially. Many people think that turning a literary source into a film essentially amounts to moving the bones from one graveyard to another. But making a film based on a published source is a lot closer to making a film based on an original script than many would like to think. I loved your short story, The Lone Star Cowboy, but I knew that in order for it to work as a film, I would have to lose a lot of things I loved about it. And that was challenging. But it was also exciting to have the opportunity to put my personal stamp on a story I had greatly enjoyed. This film was my first adaptation, and I think I learned a lot about what professional screenwriters go through when they undertake the complex task of transforming a novel into a feature screenplay.

IF COST WAS NO FACTOR WHATSOEVER (because I know that it is, but pretend it isn't for a second) would you have embarked on a feature length project? is this your dream? (It doesn't "cost" a fiction writer more to write a novel than a short story–not in dollars anyway. Just the time.)

If cost were no factor whatsoever, I would make a feature as soon as possible. (I still would have made a short film of your story, simply because I was inspired to make that film.) On the wall in my office, I have a list of goals that I would like to accomplish at some point in my life, and "Direct a feature" is one of them.

But, of course, cost is a factor, and short films are usually less expensive than features, making them lower-risk options for young filmmakers wanting to gain experience and create a body of work while keeping their bank accounts intact.

Next time: are young writers and young filmmakers ready for "big things," or should they learn from short forms first?

March 2, 2011

This is How You Do It: John Vanderslice (Part 3)

This is the end of a three-part interview with John Vanderslice. During Fall 2010, we each taught a Big Thing creative writing course. We had never met, and at the time, we had no idea we were doing almost exactly the same thing in our classes. We figured this out by accident, really, when in the course of discussing something over email with his wife Stephanie Vanderslice, I mentioned that what I was doing, and the rest is history.

John, was there anything that inspired you to try these new approaches?

Yes, two different AWP sessions.� The first, at the 2007 Atlanta conference, featured a group of teachers from Bath Spa University in Bath, England.� They described their graduate Novel writing course.� They run the course as a traditional workshop course, with the material being novel chapters instead of short stories.� Their course runs over the length of a full year and even so they don�t expect their students to finish their novels.� But they do expect them to get far along in them. Bath Spa at least recognizes institutionally that novels are what their fiction students want to write and need to write.� (They also claim that workshopping the novel as it progresses is useful to their students.� I�ll take them at their word, but from my own experience as a teacher I wonder how that is so.)

The person who really opened my eyes was Mary Kay Zuravleff who at the 2009 AWP conference in Chicago described a novel writing course she ran for her students at George Mason University. Mary Kay insisted that they finish their novels in one semester; she issued week-to-week word count goals and held the students responsible to those goals; and she gave up workshopping in favor of the more limited peer review system I described earlier. Also, Mary Kay participated herself in the course, writing a short novel of her own along with her students.

Mary Kay�s talk was a revelation. I was looking for an answer, for a new direction, and she provided me with one.� I saw immediately how more beneficial her class would be for the budding novelist than my class was. But I was worried about making undergraduates complete a book in one semester.� In fact, all of the participants in Mary Kay�s session discussed her model as something that of course would be applicable to graduate students only. In response to a question I asked from the audience, one of the other participants said to me, �Can you imagine asking your undergraduates to do this?� Well, no; at that moment I couldn�t. But I couldn�t see any better model than Mary Kay�s, and I still don�t. She gave me the courage, the �permission,� to throw workshopping out the window. For that I�m eternally grateful.

�Throwing workshop out the window.� To some, I�m sure those sound like fighting words! Yes, for this particular kind of class, one that�s about production, process, drafting, then I think you have to replace workshop with what I call �writeshop.� You have to imagine that you�re teaching a studio arts class or a dance class. I still workshop in other classes, of course. I think it�s important for people reading this to understand that we�re not saying �workshop is bad,� only that it isn�t the only organizing principle for a creative writing course. It�s simply what we�re the most used to.

The biggest change for me has been seeing my students actually complete novels, seeing them stick out the process, figure out whatever needed figuring in order to keep going. By no means were they always happy with their novels as the semester went on, but that�as I tried to explain�is a completely ordinary feeling for a novelist. The trick is to keep going. And they did. They learned how. Their novels are the result of this education.

How many of them finished?

Fifteen students enrolled in the course, four did drop out.� One student withdrew from school altogether, three more decided they would not be able to keep up with the work.� The other 11 finished the course and first drafts of their novels.� While not perfect, that�s a much higher percentage that I expected.

How good are these novels?

It�s way too early to tell if one of these novels will ever be published, but I can say that at least one, with some tinkering, does seems publishable.� The student who authored that novel is one of the most elegant and astute writers in our program, but he would never have taken on a novel�I mean as an undergraduate�if not for enrolling in the course. Now I�m convinced that his novel is the best thing he�s ever written.�� And I can also say the same thing about a novel written by another of the students.� It�s a fantasy tale written for children, rather elegantly composed in the manner of C.S. Lewis but very well done.�� I�ve had that student in class before , and his novel is superior to anything he turned in last year.� He is immensely proud of it.� It�s wonderful, almost darling, to see his enthusiasm for it.� He is actually trying to market the book now to agents and children�s literature publishers.� I hope he succeeds!

What did your colleagues say?

Those who heard about what I was doing had generally two reactions: 1) Wow, how exciting for the students, and 2) Are you actually going to read all those novels at the end of the semester?

Well, did you read them? This is not an unimportant question. What did they have to turn in at the end of the semester?

At the end of the semester my students had to turn in a finished first draft of their novels, with a word count of at least 55,000.� A couple students actually went over that total.� One student wrote as much as 78,000 words.� And yes, despite what I said about not providing them week to week feedback, I did feel it was incumbent on me to read these novels and give them some response, even if in brief.� Was I able to do so?� Mostly, yes, believe it or not.� I read one student�s novel over the course of the semester in the peer review group.� (The other peer group member dropped out of school.)� So at semester�s end I had 10 novels to read.� Over Christmas break I read 8 of these and emailed comments to my students.� It was not as difficult as it sounds, as these were short novels, and I was really intrigued by them, knowing they were composed by my students.� (And believe me, I am NOT a fast reader.) I�m still reading the 9th novel now.� The 10th I may never get to, I hate to say, and that student has graduated and to be honest she didn�t show a terrible lot of interest in getting feedback about it.� In short, I think it�s very important for those who teach the course to at least make an honest attempt to read the finished products.� The students deserve that.� On the plus side, while the semester was going on, the time demand of the course really was not excessive at all, no more than any of my other courses.� Maybe even less, because we were not workshopping but �writeshopping� to use your phrase.� My main worry all semester long was keeping pace with my own novel!

How were your students� grades determined?

The novel itself certainly took the lion�s share of semester �points,� about 60%.� But there were other assignments: a brief (one page) explanation of their initial idea for the novel, responses to the chapters in Baty�s book, responses to the two novels we read, end of semester reflective papers on the experience as a whole and on their peer review group.� These all counted for about 30%.� And then I gave a peer review grade, the toughest one since I had no written critiques to go by.� I had to determine that grade from my impression of how active their peer review groups had been and by what they told me in their reflective papers.� (I know that sounds iffy, but it was the best I could do.� Better that than to have them not accountable at all.)� So this was the last 10%.� As far as the novel itself goes, I did keep track week to week as to whether or not they met their word count goal.� At the end, if the student turned in the novel and had met all his word count goals through the semester he got full credit.� Any undergraduate who can finish a draft of a 55,000 word novel in one semester certainly deserves as much�even if the thing stinks.� (Which, for the most part, really didn�t.)