Cathy Day's Blog, page 11

December 15, 2012

Protected: On the Anniversary of Her Passing

December 11, 2012

Last Lecture: What matters more: Story or Sentence?

Every time I teach novel writing, I end the semester with a “Last Lecture” on a topic that’s been on my mind all semester long. Last spring, I wrote about learning to self-identify as a writer; this post, “Am I Writer?” has been viewed about 1,500 times. And Google Analytics tells me that people spend an average of eight minutes on this post–which is not that surprising when you consider how urgently people need an answer to that question. This semester, I’ve decided to write about whether a novelist should focus more on The Story or The Sentence, using the occasion of announcing who won my “Most Words Drafted Contest” to reflect on the topic.

The Announcement

Here are the two students who won the Total Word Count Challenge: Kayla Weiss (85,007 words) and Kameron McBride (43,880 words).

Kayla Weiss

Kayla averaged over 7,000 words a week, or 28 pages a week, for 12 weeks. This is really sort of amazing.

Kameron McBride

Kameron averaged about 3657 words a week, or 14 pages a week, for 12 weeks. Also pretty amazing.

Scroll down to see how many other students took this challenge and did really well. What’s significant about this is that they were only required to turn in 2,250 words per week as their “Weekly Words,” which I talk about here.

Observations

This is the second time Kayla has taken my class, and she won last time, too.

Kayla started the semester writing one novel, but discovered that she really wanted to work on a different project. For awhile, she alternated between the two projects before finally committing to the second manuscript. This is smart. When you run out of steam with one manuscript, don’t just stop writing. Pull up another manuscript.

Kameron says that what really helped him was using 750words.com. It provided a clean, uncluttered writing space that he’d keep open on his laptop during the day.

What were their novels about?

I don’t want to give too much away, because both novels have good premises.

Kameron’s is sort of a meta-horror novel. Kayla’s is part of a trilogy she’s been working on for a few years.

Kayla and Kameron won a year’s subscription to Poets & Writers.

You can continue following their writing journeys here:

Kameron’s Twitter

Kayla’s Twitter

Runners up

ENG 407-2

Scott Bugher 65,878

Andy House 62, 353

Sarah Hollowell 52, 025

Amy Dobbs 38, 365

Jackson Eflin 32, 971

Samantha Zarhn 27, 393

407-3

Kiley Neal 40,910

Aaron Beal 38, 167

Katelyn Wilhelm 33, 857

Christian Jones 31,915

Hilary Wright 30,694

Aaron Price 27, 555

The Last Lecture Begins!

Why did Kameron and Kayla win? What set them apart?

Both wrote scene-driven fiction with lots of dialogue. They took my advice and “sketched” their novels, temporarily suspending concern for “good writing” at the sentence level and focused on “getting the story down.”

In Anne Lamott’s famous essay “Shitty First Drafts,” she makes a distinction between the Down Draft (getting the words down on the page) and the Up Draft (fixing up the words on the page). What I’ve learned from teaching this class for a few years is that those of you who are able to compartmentalize the writing process into these two modes have a much easier time getting your Weekly Words done. The class itself all but demands that you do Down Drafts, although many of you just cannot bring yourselves to write shitty first drafts and spend a lot of time doing Down and Up drafting simultaneously. This is fine. It’s your life. It’s your time. But it won’t give you a better grade.

Are their partials flawed at the sentence level? Do their manuscripts show signs of having been written quickly?

Yes. Definitely.

But so did yours.

And this is okay with me. In this particular class.

Why? Because ultimately, I think that you have a better chance of publishing a novel if you can learn how to write a sort-of-shitty first draft. Because before you can publish a novel, you have to actually write one. The whole freaking thing.

Sentence vs. Story

I don’t understand why some people simply do not recognize awkward writing (their own or someone else’s).

I don’t understand why some people simply do not recognize awkward writing (their own or someone else’s).

And yes, I also recognize that what constitutes “good” and “bad” writing is rather subjective. (Here’s a great article about that.)

In his essay “It’s a Short Story” about his own creative writing apprenticeship, John Barth said, “I [had] an all but reality-proof sense of calling, an unstoppable narrativity, and I believe a not-bad ear for English.” He compares this kind of writer (driven, prolific, a decent wordsmith) with its opposite, “Young aspiring writers with a strong sense of who they are and what their material and their handle on it is, but little sense of either story or language…by far the less promising, although I would be reluctant to tell the patient so.” Barth believed that “essential imaginativeness and articulateness, not to say eloquence, are surely much more of a gift.”

I’m living proof that even if you lack those essential gifts, you can develop them. I wouldn’t teach creative writing if I didn’t believe this was so.

However, I’ve been teaching fiction writing for almost twenty years now, and one thing I’ve discerned is that my students always fall into one of three groups:

A. Students who are proficient at the sentence level but suck at story.

B. Students who are proficient at the story level but suck at sentences.

C. Students who are proficient at both. (Rare.)

I can tell within a paragraph or two whether someone is an A. I know it because I’m able to “just read” the prose. As Hawthorne said: “Easy reading is damn hard writing.”

And I don’t mean that the A’s write “lyrical prose.” I mean they can write what I like to call “invisible prose,” functional sentences that do not distract nor draw attention to themselves. It’s prose that’s maybe just a tad underwritten, the opposite of overwritten. An A is novelist who can do what Willa Cather was talking about here:

“I don’t want anyone reading my writing to think about style.

I just want them to be in the story.”

It takes a lot longer to discern whether someone is a B, proficient at the story level, which is more about structural skill. Because I have to read the whole thing.

Honestly, my least favorite kind of student is a B, the ones who suck at sentences. They are my least favorite because I’ve never–not in 20 years–been able to figure out a way to help them other than to point out their weak sentences. This is what my MFA thesis director, Thomas Rabbitt (a poet) taught me: how to take out my own eyeballs and read my work through the eyes of someone else.

Honestly, a creative writing student who cannot consistently craft a graceful, clear sentence is (to me) the equivalent of a music major who can’t carry a tune or a colorblind art major.

I’ve had more than one student tell me that great stories take shape in their heads, and they speed-write them down because they speed read fiction, too. They consume stories as quickly as possible, and so when they turn to writing–not reading–stories, they do the same thing. Having spent years ignoring sentences for the sake of “getting the gist,” they unconsciously assume that readers won’t notice the sentences.

Honestly, that’s exactly how I read when I was young. Voraciously. Quickly.

I accomplished this by reading the scenes only and skimming the words and paragraphs in between the scenes. I’d learned that all the important plot points were almost always conveyed in scenes, so my eye would travel down the page until I found a sentence like, “Cassandra took a deep breath and prepared to enter the sitting room.” Or I’d look for an exchange of dialogue—which is usually apparent to the eye just by looking at a page.

I accomplished this by reading the scenes only and skimming the words and paragraphs in between the scenes. I’d learned that all the important plot points were almost always conveyed in scenes, so my eye would travel down the page until I found a sentence like, “Cassandra took a deep breath and prepared to enter the sitting room.” Or I’d look for an exchange of dialogue—which is usually apparent to the eye just by looking at a page.

I focused on the scenes only because it was scenes that brought me into the vivid and continuous fictional dream of the story, and that’s the experience I wanted: to crawl into the dark portal on floor 7 ½ and be inside John Malkovich or Stephen’s King’s Carrie White or Judy Blume’s Tony Miglione or C.S. Lewis’ Lucy and Edmund Pevensie. I didn’t much care if the main character was male or female, young or old. I just wanted to be inside them for awhile until the book ended and I found myself stranded along the New Jersey Turnpike.

Discovering Sentences

And then something happened.

My sixth-grade teacher required us to memorize the Gettysburg Address. Did Mr. Schwartz read it aloud? Did we watch a video or listen to a recording? I don’t remember. But still, I recognized the beauty of those words without being presented with external evidence of the way they should sound. Just by reading them on the page, I heard the cadence, the rhythm, the inflection, the musicality of the words in my head.

But when it came time to recite them from memory in front of the class, my classmates delivered the address in a rushed monotone:

Fourscoreandsevenyearsagoourfathersbroughtforthonthiscontinentanewnationconceivedin libertyanddedicatedtothepropositionthatallmenarecreatedequal.

This is when I realized that stories are made of sentences capable of providing their own pleasures. It was as if I’d never noticed sentences before–and suddenly–there they were!

I realized that words are variables in a syntactical equation, and if you can come up with the right order, the perfect equation, those words can affect people.

In How Fiction Works, James Wood writes: “There is a way in which even complex prose is quite simple—because of that mathematical finality by which a perfect sentence cannot admit of an infinite number of variations, cannot be extended without aesthetic blight: its perfection is the solution to its own puzzle; it could not be made better.”

Exactly.

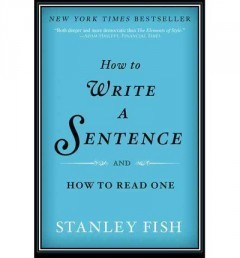

If I had my druthers, if students had to “audition” for undergraduate creative writing programs the way they audition for other arts programs, I’d pick the A’s over the B’s. Every time. Because I believe it’s much harder to teach someone how to write a good sentence than it is to teach them how to write a good story.

Feel free to disagree with me if you want.

Micro vs. Macro

Perhaps now that I’ve told you how much I value good writing at the sentence level, you can appreciate how difficult it is for me to teach a class in which sentence-level proficiency isn’t all that important.

Perhaps now that I’ve told you how much I value good writing at the sentence level, you can appreciate how difficult it is for me to teach a class in which sentence-level proficiency isn’t all that important.

What counts is that all of you did exactly what I asked you to do: start writing a novel as fast and as well as you can.

As I read all of your partials these last few weeks, I could have marked an infinite number of things that weren’t working yet or needed to be fleshed out or needed to be eliminated. But I tried really hard not to do that. I tried not to focus on the micro and focused on the macro instead.

But don’t forget the micro is really important.

In the film A Beautiful Mind, John Nash looks at a wall of numbers—intercepted radio signals from Moscow, supposedly—and some official-looking dudes ask him to break the Russian’s secret code. He stares at the numbers. Some begin to glow more brightly than others. He’s able to look past the physical numbers and discern emerging patterns under and within the numbers.

It’s like me, seeing the sentences under and within a story for the first time.

In the film Amadeus, Salieri hears “the very voice of God” just by perusing Mozart’s sheet music. As he reads the notes on the page, we hear the fully orchestrated music inside Salieri’s head. He doesn’t need to hear the music played to know that “displace one note and there would be diminishment. Displace one phrase and the structure would fall.”

What I’m trying to tell you is that a good book operates on many levels.

Sentence.

Scene.

Story.

It takes a while to discern those levels—if you ever do. And it takes a while to acquire proficiency at all those levels—if you ever do. This semester, we focused on Scene and Story, but make no mistake: Sentences Matter.

December 6, 2012

“I can’t do this anymore.”

I’m starting to wonder if teaching a novel-writing class with 15 students can really be done.

Let me explain.

This semester, I taught Advanced Fiction, a 400-level course at Ball State which I teach as a novel writing class. The course is capped at 15, and so, because I was assigned two sections, I had 30 students writing novels for me this semester.

Let’s do the math.

Each student wrote 2,250 words a week (about 9 pages of any quality) for 12 weeks.

Multiply that by 30 students, which means my students produced:

67,500 words (270 pages) a week

810,000 words (3,240 pages) over 12 weeks

They turned in their Weekly Words via email. I created a special gmail account to receive these messagess so that they would not get lost amid the 50-100 other emails I get every day.

30 emails a week over 12 weeks = 360 emails to open, digest, file away.

To make this process easier on me, I asked them to include the following information every single week:

their logline (a one-sentence description of the plot)

the context of the words (“finishing chapter 2 this week,” or “This week, I banged out a lot of plot points,” or “random scenes,” or “I journaled some questions and concerns for awhile, then moved into some scenes from what I think will be the prologue.”)

Then they attached the document that contained their Weekly Words.

I’ve already written about how I “read” these email attachments, which is to say that I look them over but don’t respond.

Logging in their Weekly Words takes about 2 hours a week.

Meanwhile, I read and grade other things they write. Their quizzes (I give really long in-class reading quizzes), their reverse storyboard projects (where they take a book apart and write about what they learned), short response papers, etc.

This will not surprise you: it’s really hard (but not impossible) to absorb this many stories coming at you at once. But within a few weeks, I do get to a point where I remember what each of them is writing about.

For twelve weeks, they send me the fragile stirrings of their novels. It’s weird feeling to receive those 30 emails every week, something strangely intimate and kind of a privilege. I treat their words very carefully. I acknowledge the receipt of their Weekly Words by sending a brief reply. I don’t say much other than “Thank you,” or “Keep going!” or maybe “I liked the scene at the party.”

It’s way too early to say anything critical.

And pedagogically speaking, it is relatively easy to read through words and pages I don’t need to respond to critically. Yet.

The Consequences

The ConsequencesStill, it’s a lot of words coming at me. Even if I’m not commenting, I’m still making room in my head for all those words and stories. There are definitely consequences.

I watched a lot of TV and movies this semester.

When friends and former students asked me to read drafts of their novels and memoirs (this happened about once or twice a month), I had to say “No. I don’t have any more room in my head.”

I worked on my own book project until about Week 8, and then I had to stop. This happens most semesters, though, even when I’m not teaching novel writing.

Eventually, I *do* have to read and respond to them all. (More on this later.)

Comparison

Now, if this were a different class, a “normal” fiction workshop, I wouldn’t be quickly reading 270 pages a week. I’d be carefully reading maybe 50-150 pages of fiction due to be “up” in my workshop that week.

And so would all 30 of my students.

See, the students in my classes aren’t looking at 270 pages a week. Only me. There is no all-group workshop in my class. They’re expected to spend a lot more time writing their own stuff than they spend reading the work of their peers.

In fact, for many weeks, they really have no idea what anyone else is even writing about.

The Climax of the Semester, or Shit Gets Real

Then, in week 14, they have to turn in a partial, which I define as the first 25-50 pages of the book.

By this point, I’ve put them in small groups—the ones writing realism, the ones writing fantasy, etc.—and they read only those partials. I don’t even call these discussions “workhop.” I call it “beta reading.”

But—and you saw this coming, right?—I have to read them all. This is when things get really, really hard.

25-50 pages times 30 students = 750-1500 pages.

This is how I do it

This is how I do itI’ve been an MFA thesis advisor. This is nothing at all like that. No way. Thesis advising involves reading at both the micro and macro levels. This is macro only.

To keep myself from doing line edits, I send the documents to my Kindle. This keeps me from marking all over them. I try to “just read.” I make a few notes to myself.

I don’t type a critique. Each student makes a 30-minute appointment, so I give my feedback orally. They walk out with a rubric where I’ve marked the things they need to work on for the revision (due at the time of the final).

I spread these appointments out over 2 and 1/2 weeks, doing about four a day. Which means I read just four a day. That’s all I can hold in my head.

So Tuesday, for example, I had four appointments scheduled, plus a meeting and a class to teach. I read one partial Monday night before I went to bed, then got up about 6:30 to read the other three. Got dressed. Went to school. Taught. Conferenced. Came home. Had dinner.

As I write this now, I have five appointments scheduled for Wednesday which means five partials or about 200+ pages to read, and I’ve only read one of them. And my morning reading time is gone because I’m teaching from 9-12 in the morning.

So every word I’m writing here is cutting into the time it’s going to take me to read those 200 pages.

But I needed to do the math.

Conclusions:

There’s a good reason why very few people teach novel-writing classes comprised of 15-20 students. BECAUSE IT’S REALLY REALLY HARD.

Even spread out over 2 and 1/2 weeks, I couldn’t handle that many pages coming at me and that many conferences in an otherwise already full life. My physical therapist and my yoga teacher/masseuse and my husband tell me all the time, “If you don’t have time to take care of yourself, something’s wrong.”

The traditional workshop structure guarantees that you read works-in-progress at a reasonable rate, one at a time, a few a week. Not 30 at a time in dribs and drabs for 12 weeks and then boom, 30 manuscripts fall in your lap (or into your Kindle).

There must be a way to make this work. I think I’ve ALMOST got it figured out.

I can’t ever teach two sections of this class again. Luckily next semester, I have just one section.

Rather than schedule individual conferences, I’ll be a part of the beta reading groups.

But how can I do that when they’re all discussing at the same time in small groups? Aha. I’ll put them in groups 3 groups of five. The week I spend discussing the mss. of Group 1, Groups 2 and 3 will get in-class writing “studio” time (which they already do anyway). So: I only have to read five partials a week for three weeks, and I don’t have to schedule conferences because they will have gotten my feedback in class.

I’m also considering reducing the partial to 10-25 pages, which is actually more in line with the industry standard anyway.

I started writing this post because I was convinced I couldn’t teach this class anymore. You can only do what you have the resources to do. But of course by the end, I think I’ve figured out a way to make it work better.

More Math.

These are the numbers that count.

Most Words Drafted Contest (top 7)

ENG 407-2

Kayla Weiss 85,007

Scott Bugher 65,878

Andy House 62, 353

Sarah Hollowell 52, 025

Amy Dobbs 38, 365

Jackson Eflin 32, 971

Samantha Zarhn 27, 393

Each of these students wrote more than the required 2,250 words a week.

I’m convinced that the real test of teaching is figuring out a way to make your students feel like they’re working and learning WHILE ALSO making sure you yourself are staying productive as a writer. Because how can I expect them to write if I’m not? I think I’ve almost got this class to a point where we’re all writing and nobody’s buried.

I’ll report back next semester and let you know.

October 18, 2012

Is “literary citizenship” just a nice way of saying “hype?”

Last week, I created a mid-term survey for my novel writing class. I wanted to know how things were going. Fine, it seems, but I did get this comment: “Though the class has a solid layout, I feel it’s taught with an assumption that each student intends to measure their success with book sales, awards, and film adaptations. It might help to keep in mind some of us are more motivated by art than the latest trends and approaches to win a broad audience and sell a ton of books.”

Last week, I created a mid-term survey for my novel writing class. I wanted to know how things were going. Fine, it seems, but I did get this comment: “Though the class has a solid layout, I feel it’s taught with an assumption that each student intends to measure their success with book sales, awards, and film adaptations. It might help to keep in mind some of us are more motivated by art than the latest trends and approaches to win a broad audience and sell a ton of books.”

Reading your own teaching evaluations is a deeply humbling experience, not much different from reading workshop critiques. Scary as it can be, it’s also kind of fascinating to read what people think about you. Positive critiques are great, sure, but it’s what you do with the negative ones that determines what kind of person you are.

As much as it dismays me that the student above thinks that my class is about crass commercialism, I can’t deny that my pedagogy has turned toward the practical in the last few years. I focus less on product and more on process. I teach students (including undergraduates) how to write and sell a novel, as well as how to use social media to connect with other writers and readers. My novel-writing textbook is called Writing the Breakout Novel, for heaven’s sake.

My students have definitely reacted to these changes. Here’s a few comments from my anonymous teaching evals over the last year or so:

“Although Professor Day is knowledgeable and interesting, perhaps too much emphasis was given to social networking (twitter, blogger) rather than to fiction writing.”

“Cathy does a wonderful job of teaching beyond the craft of writing (although she does that very very well) to the “art” of getting oneself published. I appreciate that she is up on the technology and social networking needed to get one’s name out there and be recognized, published, and marketed.”

“Some of the business of being a writer conversations were a little overwhelming at the time, but I think it will ultimately be valuable knowledge.”

A few months ago, I asked here “Should we make it our business to teach the business of being a writer?” and friends and strangers chimed in to say, “Craft should always be the most important thing. With regard to the ‘business of writing,’ a little goes a long way.”

All this is very much on my mind as I prepare to teach my course on Literary Citizenship next semester. My worst fear is that my students and colleagues will think I’m teaching a class called “Self-promotion, Horn Tooting, and the Art of Hype,” which—let’s be frank—is sort of what I’m doing, only I want it to be the exact spiritual opposite and come from a place that’s outward focused, not inward focused.

I don’t know about you, but when I need to think about something good and hard, I teach a class on it. And these are the questions that have consumed me for the last few years as a writer:

How can I be a decent human being AND get you to buy my books?

How can I be a writer “you’ve heard of” without turning into some version of myself I can’t fucking stand?

I know it’s important to write the absolute best book I can, yes yes yes, but how much do I need to toot my own horn in order for that book to be read?

And I’ll bet if you’re my age or older, you think about this a lot too.

Today I read an article on the Virginia Quarterly Review website in which writer Sean Bishop dared to ask the question, “What’s the difference between self-publishing and publishing with a small press?” I found myself nodding a lot as I read it, but I also agreed with some of the nay-sayers in the comments, especially the one who noted “We’re all bloggers now, and no, we’re not readers so much as self-promoters and readers of self-promotion.”

Sigh.

I’m reminded of another recent article on the VQR site, “Quality Work Does Not Speak for Itself—It Must be Marketed.” Amy Lowell’s most recent biographer Carl Rollyson wrote that, based on reading the poet’s voluminous correspondence with editors, journalists, and publishers, Lowell would have been a fan of author websites and social media as a means to promote her work and the work of other poets in the Imagism movement. She forged an “unstinting campaign to find publishers for their work, reviewers who would recognize its value, and, ultimately, audiences that would follow them.” T.S. Eliot called Lowell the “demon saleswoman of poetry” who used whatever means at her disposal to promote herself and the poets she admired. Rollyson writes, “She did not have access to the kinds of social media and electronic platforms that I’m sure would have thrilled her. She did not believe that the work spoke for itself. An author had to speak up for her work and do so with a savvy understanding of the marketplace.”

I’m reminded of another recent article on the VQR site, “Quality Work Does Not Speak for Itself—It Must be Marketed.” Amy Lowell’s most recent biographer Carl Rollyson wrote that, based on reading the poet’s voluminous correspondence with editors, journalists, and publishers, Lowell would have been a fan of author websites and social media as a means to promote her work and the work of other poets in the Imagism movement. She forged an “unstinting campaign to find publishers for their work, reviewers who would recognize its value, and, ultimately, audiences that would follow them.” T.S. Eliot called Lowell the “demon saleswoman of poetry” who used whatever means at her disposal to promote herself and the poets she admired. Rollyson writes, “She did not have access to the kinds of social media and electronic platforms that I’m sure would have thrilled her. She did not believe that the work spoke for itself. An author had to speak up for her work and do so with a savvy understanding of the marketplace.”

Rollyson says, “My point is that there has never been a period in publishing when authors themselves were not the individuals most invested in getting their work known. And in this age, for someone like Amy Lowell, that would mean contributing considerable time, energy, and money to produce the best author’s website around. You can bet she would not be against social media, labeling it some new imposition on the author, more comfortable with the easier and cozier ways that prevailed in the old days. Lowell would be the first to say that those old days are largely a chimera. She always felt she was struggling to be heard, even though her books sold out and went into second and third editions. She never let up.”

By the way, it’s no accident that both of these conversations started at VQR. Jane Friedman, a long-time editor and social media expert, is the new Web Editor at VQR, and Jane’s been talking about “the business of writing” for years at conferences and on her blog. Jane is the space on a Venn diagram where the Poets & Writers world and the Writer’s Digest world overlap in interesting ways, and lately–as I work with the Midwest Writers Workshop and teach my novel writing class and prepare to teach a course on Literary Citizenship–I’ve been spending a lot of time in that space, too.

I’ll leave you with a great quote by writer/director Charlie Kaufman I found via writer Julianna Baggott. This baby’s going on the syllabus for my Literary Citizenship class, fer sure. On September 30, 2011, he addressed BAFTA as part of their Screenwriters’ Lecture Series. Kaufman said:

I do not want to be a salesman, I do not want to scream, “Buy me!” or, “Watch me!” And I don’t want to do that tonight. What I’m trying to express–what I’d like to express–is the notion that, by being honest, thoughtful and aware of the existence of other living beings, a change can begin to happen in how we think of ourselves and the world, and ourselves in the world. We are not the passive audience for this big, messed up power play….The world needs you at the party starting real conversations, saying, ‘I don’t know,’ and being kind. Think, “Perhaps I’m not interesting but I am the only thing I have to offer, and I want to offer something. And by offering myself in a true way I am doing a great service to the world, because it is rare and it will help.

Actually, maybe I need to read that quote in class right away.

October 15, 2012

CIRCUS at NAMT

Okay, so let me try to explain what this all means.

Okay, so let me try to explain what this all means.

A few months ago, the National Alliance for Music Theatre (NAMT) selected The Circus in Winter as a finalist in their yearly new work competition. NAMT’s 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals is a premiere industry event that gathers theatre industry leaders to discover promising new musicals. Hundreds of scripts are considered but only eight are chosen; at the two-day festival, they give two abbreviated, 45-minute performances. Professional, age-appropriate actors are cast in the roles. Basically, it’s a major stepping-stone towards a Broadway production. Ever heard of Thoroughly Modern Millie? The Drowsy Chaperone? Well, they got their start at NAMT.

An imperfect analogy for my readers who know diddly squat about the world of musical theater (myself included until recently): a musical created by college students getting picked for NAMT would be like a high school kid getting a Breadloaf or Sewanee or Stegner fellowship.

Unprecedented.

All I can really say right now is that Circus was definitely a hit. NAMT rules stipulate a 4-6 week cooling-off period after the festival, which means I’ve got nothing specific to tell you except that many regional theaters expressed interest in Circus. If you follow the link for Millie above and check out its production history, you’ll see that that’s a possible route to Broadway: out-of-town tryouts at regional theaters.

Here are some pictures from the day I went to NAMT.

Me and Beth Turcotte, who has worked tirelessly for three years to get CIRCUS to this point. She’s amazing, and I’m so grateful to her.

Now, at this point, I’ve seen Circus about 10 times, but this time was different. I’ve enjoyed all the wonderful performances by Ball State students, but this time, the roles were played by professionals, and their voices filled the room.

The cast takes the stage.

I cried a little bit during the first song. I mean, holy shit, Sutton Foster was up there playing Jennie Dixianna. Seriously, who thinks anything like that will ever happen?

I was so happy that my agent Sarah Burnes and Andrea Schulz from HMH (and whose sister went to Ball State! small world!) were able to come and see the reading.

I was also happy to meet the other cast members and thank them. I told Steel Burkhardt that his character, Wallace Porter, was named partly for the real circus owner from Peru (“Lima”) Indiana, Ben Wallace, and for my hometown’s most famous son, Cole Porter.

Irene was played by Kate Rockwell, Emory by Corey Mach, and Wallace Porter by Steel Burkhardt.

But I was also incredibly happy to see Emily Behny on stage, playing Catherine. She was in the class that wrote the musical, and she’s gone on to star in the national tour of Beauty and the Beast. And two other students from the class were on stage: the original Wallace Porter, Jonathan Jensen, and percussionist Nick Rapley, joined by Joe Young, who played banjo and mandolin in the BSU production. And of course Bill Jenkins was there. He’s the chair of the BSU Department of Theatre & Dance, someone who understands not only how to make things happen inside a university (which is hard) but outside it as well (which is harder).

Christopher Swader, Nick Rapley, Joe Young, Ben Clark, Beth Turcotte, Justin Swader, and Jonathan Jensen

It was strange to see Ben Clark introduce the show and then take a seat instead of grabbing his guitar. In my mind, he’s always been one of the characters. But he has another role to play now, one he still performs beautifully.

Beth and Ben greet their adoring fans.

And yes, Perez Hilton really was there. I didn’t see him, but Emma Turcotte did and snapped this picture.

Perez.

A few people have asked me, “So did Circus win at this festival?” Which is a fair question and certainly one that I asked myself. Even though there aren’t first, second, and third prizes or Palm d’Or’s or anything like that, trust me: things really could not have gone better at NAMT than the way they did. In a month or so, I should be able to tell you what exactly is going to happen next with the musical.

I can’t wait to find out!

I want to thank everyone for making me feel a part of this journey.

September 23, 2012

My Next Big Thing: Literary Citizenship

For the last few years, I’ve ended my classes with a presentation/pep talk on Literary Citizenship (basically this post as a Power Point). But next semester, I’m going to teach a whole class on Literary Citizenship.

For the last few years, I’ve ended my classes with a presentation/pep talk on Literary Citizenship (basically this post as a Power Point). But next semester, I’m going to teach a whole class on Literary Citizenship.

Course descriptions are due this week, so I just wrote this up:

A literary citizen is an aspiring writer who understands that you have to contribute to, not just expect things from, the publishing world. This course will teach you how to take advantage of the opportunities offered by your campus, regional and national literary communities and how you can contribute to those communities given your particular talents and interests. It will also help you begin to professionalize yourself as a writer. You will learn how to 1.) create your own professional blog or website, 2.) use social media to build your writing community, 3.) interview writers and publish those interviews, 4.) review books and publish those reviews, 5.) submit poems, stories, and essays to literary magazines, 6.) query agents and editors regarding book manuscripts, 7.) apply to graduate programs and write an effective statement of purpose, 8.) deliver an effective public reading of your work, 9.) pitch to an agent, 10.) craft a professional résumé. Students who complete the course in an exemplary fashion will be eligible to apply for internship positions as Social Media Tutors at the Midwest Writers Workshop in Muncie July 25-27, 2013.

I really hope that the internship positions mentioned above will be PAID positions. See, one reason why I haven’t been posting here at the Big Thing lately is that I’ve spent the last month writing a grant that would provide fifteen paid internships to Ball State students so that they can participate in the Midwest Writers Workshop (MWW), an annual writers’ conference which takes place in Muncie. I’ve written more about it here.

This past summer, I convinced four of my students to work as Social Media Tutors. Basically, the tutors taught the attendees how to start a blog, how to use Twitter and Facebook effectively, how to create a platform (or as I like to call it, how to connect meaningfully with people).

Me and the Tutors. From left: Maye Ralston, Ashley Ford, Spencer McNelly, and Tyler Fields. They’re wearing T-shirts with their QR codes on them. Photo provided by Maye Ralston.

Really, it was just a matter of putting a bunch of people looking for new media skills into the same room with people who had those skills. I got the idea one day when I received an email from Writer’s Digest about an online class they were offering, “Social Media 101,” taught by Dan Blank. I read the course description (and saw the price tag) and thought about my friend Cynthia Closkey, who I paid to help me set up this blog and taught me how to use Twitter. I thought, Couldn’t my creative writing students get freelance work offering “author services” like website development, social media consulting, and developmental editing? Certainly, they don’t have as much experience as Cindy, or the credentials of Dan Blank, but hey, everyone has to start somewhere.

I chose these four students because they were already using social media in a professional way. I mean, check out their bios. They were already literary citizens. They already had a student group called The Writing Community. (Students at Ball State have been learning this from my colleague Sean Lovelace for years.)

So, I tried to explain what I thought a social media tutor was. The students said, You want us to teach other people how to do what we basically do for fun?

I said, You don’t know how many people out there are desperate to understand the things about social media you guys just take for granted.

And it worked. The students felt like professionals, got a line on their resume, and the attendees were enormously grateful for their knowledge.

For the last few years now, I’ve been thinking about professionalization in creative writing programs, about whether we “should we make it our business to teach the business of being a writer.”

What brings most people to the creative writing classroom isn’t simply the desire to “be a writer,” but rather (or also) the desire to be a part of a literary community. Perhaps this is why so many undergraduates want to pursue an MFA, because “more school” is definitely something they know how to plug into. They want to be writers, and they think an MFA is what comes next. But I want to show my students that being a literary citizen can also provide that sense of community and connection they’re longing for.

So here I go again, trying to figure out how to teach yet another class I’ve never taught before.

Literary Citizenship is my next Big Thing.

I’ll keep you posted here. I also created a course blog here.

August 11, 2012

Why Do Writers Need Letters of Recommendation?

Ugh.

Today, I got this question: “How do I go about getting Letters of Recommendation for places like Breadloaf and Yaddo? I didn’t get an MFA. I’m older than the average Bright Young Thing applicant. Might we question the very system that requires LORs in the first place?”

This is a really good question. (You can read the question verbatim here, in the comments section.)

I just checked my Google Analytics and discovered that “MFA FAQ: the LOR” is the #1, most-read blog post at The Big Thing. Viewed about 2000 times since I posted it in Oct. 2011, it was composed with a college-age student in mind, someone applying to MFA programs for the first time. But I realize that lots of people need LORs—even me!

So, here’s the advice I gave.

I know what you’re talking about. It’s much harder to get letters when you’ve been out of school for awhile. Actually, the other day I was thinking about applying for a fellowship, but I had a hard time coming up with three writers familiar enough with my work to do a letter for me. Most of the writers I know are 25 years old. It’s also hard to find writers willing to blurb your book or write you a letter for academic positions.

Like you, I hate asking for letters and blurbs. Because I know how much time it takes to do them well.

A few years ago, I realized that I was going to have to start making it part of my “job” as a writer to know other writers, to be a part of a literary community, basically “to know people.” I don’t like to call it “networking,” but it is something I do more consciously now than I did 10 years ago.

If you’d like to go to Breadloaf, Yaddo, etc., let me suggest some possibilities for you that don’t involve dismantling the system:

–Ask the editors of the magazines where you publish work to vouch for you.

–Go to a writers conference like the Midwest Writers Workshop (I’m on the committee) or the Pacific Northwest Writers Association conference or the Imagination conference, just to name a few. If you have the opportunity to have your work read by an author there, jump on it.

–Take a class (IRL or online) via a writers’ center, such as The Writers Center of Indiana or Grub Street or The Lighthouse Writers Workshop. Your instructors can then write letters for you.

–Or maybe through one of these experiences, you’ll develop a friendship with another writer with whom you can trade work. If that person has some credentials, maybe they can write a letter for you when you need one.

–After checking out your blog and the subject of the book you’re working on, I’d suggest proposing a WWII-themed or historical fiction/nonfiction panel for AWP. Write to people you admire who might potentially be able to blurb your book or write LORs for you and ask them to be on that panel.

–Also, it has never been easier to “know” writers via social media. Some of my students have formed mentor-like relationships with writers they’ve met on Twitter, Facebook, or blogs. You have a blog. Have you met people via your blog? Do you comment on other people’s blogs? Are you part of an online conversation, or do you feel like you’re posting into a vacuum?

–If you practice even some of these principles of Literary Citizenship, you will get to know people. I guarantee it.

Also, here’s this: I write a lot of letters for people trying to go to places like Yaddo and Breadloaf, know lots of people who try to get into those places, people who are young and sexy and/or well connected, and they often can’t get in either. We’re in a really competitive field, as you know.

But maybe what you’re really asking about is WHY DO WE NEED LETTERS AT ALL? Why can’t the work speak for itself?

Well, here are some reasons.

–Because LORs play an important role in the vetting process.

–Because they help to weed out (but do not totally eliminate) candidates who might be crazy, dangerous, ill prepared, etc.

–Because when you’ve got 300 candidates for 10 spots, you really do need to weigh as many factors as possible, and taking into account the word of someone who knows candidate really does help.

–Because LORs are basically the same thing as the old-fashioned Letter of Introduction. When Hemingway was heading to Paris, he asked Sherwood Anderson to write him a letter of introduction so he could meet Gertrude Stein, and Anderson obliged–one of the reasons Hemingway’s criticism of Anderson in Torrents of Spring was (to me) a huge betrayal.

–Because if you’re Gertrude Stein, or Breadloaf, or Yaddo, and there are all these people who want to come into your house, how do you decide who to let in? You can’t just open the door. That’s probably not safe or practical. You have to figure out a way to screen, and it’s just human nature to ask someone, “So, you know X, right? What do you think?”

–Because this is how we apply for jobs, too, by offering up a list of names of people who can vouch for us.

I hope I don’t sound patronizing. I’m sure you understand all this. I know how frustrating it is when you feel like certain clubs are closed to you. Oh, do I know that feeling. But my advice is: don’t let yourself get angry and resentful. Think of it as a challenge, as part of the process of becoming the writer you want to be.

We can rail and rail about the adage, “It’s who you know,” or we can accept that it’s just a reality that’s never going to go away and prepare ourselves to start knowing people–not in a skeezy, opportunistic way, but rather in a professional, positive, way.

The more good people we have in our lives, the better, right?

July 31, 2012

Protected: Finding (and Cultivating) Your Writing Mentors

July 17, 2012

The Girl with Big Hair

My freshman ID card, circa 1987.

On Thursday, July 19 at 7 PM, I’ll be at the new Indy Reads Books reading a story called “The Girl with Big Hair.” Here’s why you should come.

Because I had some rockin’ hair in 1987. Admit it.

Because you’ve probably never read this story. It was published in The Gettysburg Review in 1999. The story concerns Jenny and Ethan Perdido, characters in The Circus in Winter, but because it’s not set in Lima, Indiana, the editor and I decided it didn’t quite fit into the book manuscript.

Because it’s about my internship at Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. In 1990, I went to New York with a bunch of other Midwestern college kids. We lived in a Chelsea brownstone and did internships by day and roamed the city by night—and got college credit! It was glorious.

Because it’s about my internship at Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. In 1990, I went to New York with a bunch of other Midwestern college kids. We lived in a Chelsea brownstone and did internships by day and roamed the city by night—and got college credit! It was glorious.

Because one of the other kids in this program was this guy from Wabash College named Eric Kroczek, who I clicked with immediately but pretty much blew off.

1990, New York City. Eric and I are far right.

Because when I sat down in 1995 to write a story about my Interview experience, I remembered blowing Eric off and put him in the story. I changed his name to “Nate.”

Because when Comeback Season was published in 2008, I was interviewed on WFYI’s Art of the Matter, and Eric Kroczek/”Nate” was living in Indianapolis, driving to the grocery store, and he heard me on Art of the Matter. When he got home, he emailed me and we clicked again and a year and a half later, we got married—17 years after we met in New York City.

[This is where it all comes together.] Because that interview that Eric was listening to was conducted by Travis DiNicola, Executive Director of Indy Reads, who made Indy Reads Books a reality.

[This is where it all comes together.] Because that interview that Eric was listening to was conducted by Travis DiNicola, Executive Director of Indy Reads, who made Indy Reads Books a reality.

Because if it wasn’t for Travis, I might not be happily married.

Because, to thank Travis, I’m bringing wonderful things to give away to people who come to the reading with books to donate., including a vintage issue of Interview magazine that is featured prominently in the story I will be reading.

Because the best reason to come to the reading is that you’ll be supporting a new bookstore in downtown Indy as well as a nonprofit that brings literacy to adults in Indianapolis. That’s something you can feel pretty great about.

And if all of that is not enough to convince you to come to this reading, I offer this: my parents will be there, and they are really, really cute.

My parents circa 2004. Still this cute.

Details!

Thursday, July 19 at 7:00 PM at 911 Mass Ave., Indianapolis.

Bring books to donate! There will be a drawing! Win things!

Here’s the Facebook invite.

Me and the staff of Interview, circa 1990. Good times. They offered me a job! But I turned it down and went to grad school instead.

July 10, 2012

1000 Cranes for My Wedding

1000 cranes

Three years ago today, Eric and I got married surrounded by family and 1000 origami cranes, called Senbazuru.

I got a lot of questions about why I did this.

Are you Japanese?

Um. No.

Have you read Sadako and the Thousand Cranes, and if so, what does your wedding have to do with the bombing of Hiroshima?

No. And nothing.

What were your wedding colors? Those birds are so many different colors!

Why does my wedding need to be color coordinated?

Oh God, next thing you know you’ll be saying you didn’t wear white.

Oh, I wore white. Just not a white dress. A white suit.

[Sigh.] Okay, so really: where did you get the notion to fold 1000 cranes?

I loved Northern Exposure, and if you watched that show, then you might remember Adam and Eve’s wedding.

Northern Exposure, “Our Wedding” 3:22

Eric’s family folded a few hundred cranes for me (thank you), and I folded the rest during the 2008-2009 NFL playoffs. I could fold pretty fast—one crane in two minutes—and so I could crank out 20 or 25 birds an hour and still catch all the big plays.

I folded the 1000th crane during Super Bowl XLIII as the Steelers beat the Cardinals. Then I put the birds in big paper grocery bags in groups of 100.

We got married in the beautiful backyard at Eric’s parents’ house in LaPorte, and had the small reception in their sun porch. That’s where we decided to hang the cranes—in the windows that looked out over the scenic back yard.

Traditionally, Senbazuru strings are comprised of cranes stacked on top of each of other, but I wanted a little space between each bird, so I cut up drinking straws to use as spacers.

We spent the day before the wedding stringing. Forty birds per string. Twenty five strings total.

crane straw crane straw crane straw…

Or maybe it was twenty-five birds per string, and forty strings total? Whichever. It was a lot of birds, and it was beautiful.

An ancient Japanese legend promises that anyone who folds a thousand origami cranes will be granted a wish. What did I wish for as I folded those birds? It’s hard to put into words, but it felt the way this song sounds.

No marriage is kissy poo and cranes every single day. Certainly not mine. But so far, my wish has come true. Not every single day, but most days. At least 1000 so far.

Cranes re-purposed for the reception.