Cathy Day's Blog, page 7

November 3, 2013

Every Day We Write the Books: Please, Contribute to My Tumblr

During the summer of 2013, I wanted to keep track of how many days I wrote. Like making a big fat X on a calendar. Except I don’t use a physical calendar anymore.

So I hit the Photo Booth icon on my Mac and took a quick picture, and it was saved by the date. Here’s one from May 17.

It’s how I kept myself accountable all summer. Sometimes I took a picture from the POV of my computer, sometimes from my POV looking at my computer.

I used to use 750words.com a lot. I liked sharing that a writing session had taken place, similar to how I can share an exercise session has taken place on MapMyRun. I liked that all my friends were using 750words. It felt like we were all in it together.

So at the end of the summer, I made a Tumblr that anyone can contribute to. It’s called Every Day I Write the Book.

Perhaps you think sharing info like this is bragging or narcissistic?

Well, screw you. This is for the rest of us.

This isn’t like Selfies at Funerals or Selfies at Serious Places.

This is like, Hey look at all these people who are writing!

Writing Accountability Tools

There are many ways to hold yourself accountable as a writer.

I have many writer friends who post weekly or daily updates on FB about how many words they’ve written. Personally, I like getting this information. It keeps me motivated, and they do it, I imagine, because it makes them accountable.

But yeah, I know, it gets to be too much sometimes.

Selfies

Then there’s the fact that this Tumblr is about WRITING ACCOUNTABILITY and SELFIES. At the same time!

I don’t do selfies much. I have complicated feelings about them.

I like sharing. I like offering support. I like seeing what people are wearing or that they’ve lost weight or that they’re happy or that they’ve developed a six pack or that they like their new haircut. Yay!

But yeah, I know it on the other hand, it all feels like too much sometimes.

The rules

Every time you sit down to work on your book, take a pic. Of yourself or where you’re sitting.

Keep it clean.

Be real. No sprucing or preening.

Don’t show off.

Use this to keep yourself accountable and motivated.

Submit here.

[Let's see if this works...and how it works.]

October 27, 2013

What I’ve Learned from Michael Martone

For the next few weeks, I’m going to devote my “Teaching Tuesday” posts to some of my teachers (in and out of the classroom) and what I learned from them.

For the next few weeks, I’m going to devote my “Teaching Tuesday” posts to some of my teachers (in and out of the classroom) and what I learned from them.

Lesson 1: Advocate For Your Homestate

Simply put, art is beholden to the kiln in which the artist was fired.

–August Wilson

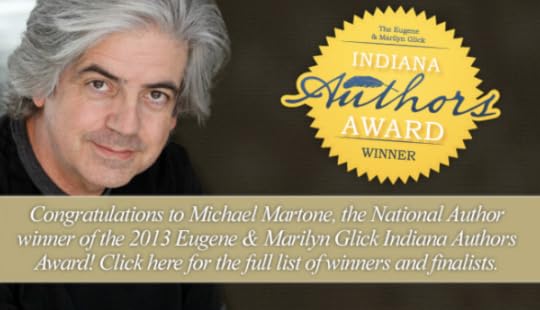

On Saturday night, I went to the Indiana Author’s Award, which is also a fundraiser and swanky dinner. The event is intended to raise awareness of Indiana authors, encourage reading throughout the state, and raise the profile of the Library Foundation and its many good programs.

There are three award categories: Emerging, Regional, and National. The and on par with such national author events as The Story Prize, etc. That such a snazzy and well-funded event takes place at all in my state both astounds and delights me. It’s only been around for five years, and I hope to God it continues, because it makes a significant cultural impact in my homestate. Praise the Lord.

The award didn’t exist when Michael Martone embarked on his literary life, but you might say he’s been working towards winning an award such as this for many years. He gave a wonderful keynote which brought tears to my eyes.

Michael recounted how, every fall for many years, he’s returned to Indiana for what he’s dubbed the Double Wide Tour of Indiana. He’d fly into Fort Wayne, borrow his mom’s red VW bug, and drive to colleges and libraries and literary centers around the state, giving readings and teaching classes for little or no money.

Which means that he’s been in a perfect position to observe (and encourage) the growth of literary culture in the state of Indiana. Much of this activity has originated within creative writing programs–and he named many college and university writing programs, my own included–but also organizations like the Indiana Writers Center in Indianapolis.

Michael probably knows the name of almost every writer in the state–from South Bend to Evansville, from the Region to Richmond. And last night at the Central Library in Indianapolis, he rattled off these names like a train conductor recounting all his well-traveled routes.

He also talked about his mother, an educator and activist, who died this past year. Before his speech, I told Michael I’d been talking with someone recently who was from Fort Wayne. When I said the name “Martone,” this woman couldn’t stop talking about Michael’s mother Patty and all her good works. Michael showed me a pin on his lapel, his mother’s Kappa Alpha Theta pansy pin, which he wears in her honor. Clearly, he’s followed in her footsteps.

But what Michael has achieved, I think, has been to make Indiana cool.

To people from outside the state who think this is just a nowhere place, just flyover country.

To people in the state who have gone to his readings and classes and thought, “Hey, maybe I should write about this weird place I call home, too.”

So many people associate “Indiana” with Michael’s work. I approach Indiana in a much more earnest and realistic manner, but so what? All that really matters to me is that someone, anyone write about Indiana in a way that’s not sentimental and nostalgic (although I am often sentimental), not about barns and basketball (although I love both of those things). Indiana needs writers who are interested in something more than the homey truths of Reader’s Digest and Guideposts.

But that’s another essay, perhaps.

Lesson 2: It’s not all about you

I was never Michael’s student in the classroom, but he has mentored me over the years–and for no other reason than because I was born in Indiana.

When he started teaching at Alabama, I’d already graduated, but I was still around, working as an instructor. When I got a campus interview for a tenure-track job at Mankato State University in 1997, I asked Michael if he would help me prepare for my first big break. And he did.

Only now that I’m a busy, mid-career professor myself do I fully appreciate that generosity.

I was most worried about the required teaching demonstration.

Michael said that if it was his interview, he would talk about how there’s no such thing as bad writing. He described a variety of contexts in which “bad writing” might be considered good.

Now, I’d never had him for a class, and so I didn’t understand that this is a very Martone-like strategy: to go meta, to zoom out a bit and question the very nature of the endeavor. In an interview, he recently said,

“I am not that kind of master teacher where I know something and transfer that knowledge to students who don’t know. Instead, I guess, I teach curiosity.”

However, to young, earnest me, it sounded a bit blasphemous. I remember saying to him, “But I think there is a difference between good and bad writing.”

He looked at me for a second, and then he said, “Ah yes, you were a student of…” and he named some of my teachers at Alabama, most of whom were gone by then. He said, “So what are you planning to do?”

I told him I planned to distribute a story I’d written and submitted to Quarterly West, then show the feedback I’d gotten back from editors. I’d discuss what advice I took, what I ignored. I hoped this would generate a discussion about workshop feedback and revision.

Michael listened and then said, “Well, the problem I see is that it’s so relentlessly about you.”

Trust me, I’ve never forgotten that zinger.

I went ahead with the teaching demonstration as planned and got the job at Mankato. Whew. But that sentence–offered privately, kindly–has stayed in my head for sixteen years. That it hurt so much at the time–I was 29–spoke to its essential truthfulness.

Honestly, it had never even occurred to me that my approach might rub anyone the wrong way. So, thank goodness he said it.

That comment pops into my head

whenever I blog

when I’m teaching and pause to offer an anecdote

when I start talking in a meeting

I ask, Is it appropriate in this moment to turn the conversation towards yourself? Sometimes the answer is yes, but often it’s no.

If you know me–in person or online–then you know I have this tendency. Perhaps you’ll find me easier to bear if you know how often that sentence plays out in my head.

You might say this blog of mine is the digital expression of that exact same impulse. Even though I offer these posts because I want to be helpful, I know that they’re often relentlessly about me.

Even this post, which is supposed to be about Michael Martone, has become about me.

So let me end with a list of ideas I’ve borrowed/stolen from Michael, and I’ll explain them in more detail in future posts.

The Town Class: the class creates a town and writes linked stories that take place in that town.

The Hypoxic Workshop: a true writeshop in which students write a story a week and focus on production rather than criticism.

A number of great anthologies that have forced me to re-think how I teach fiction writing:

Extreme Fiction: Fabulists and Formalists

Not Normal, Illinois: Peculiar Fictions from the Flyover

What about you?

If you’ve got a Martone anecdote, something to share about what you learned from him, please share it here in the comments.

October 22, 2013

Do the Math: Part 3

Time is what we want most, but what we use worst.

–William Penn

My students shared their Activity Logs with me last week. I told them that I wasn’t going to look at them. No grading. No judgement. “Be truthful,” I said, “or don’t do it at all.”

One student pointed to a block of time in between her morning and afternoon class. “Usually, I run errands during that time. Go to the library. Take care of stuff. It never occurred to me that I could schedule an hour or two of writing during that block. That’s what I’m going to do from now on.”

Another was amazed to see how much gaming he does. I was glad this came up, actually. I think our students devote many, many hours per week to RPGs and video games, esp. when you read confessions like this. I said look, there’s nothing wrong with gaming or any other pleasure activity. That’s necessary for good health and peace of mind. The problem is when that activity starts eating at the time you have for the stuff you absolutely have to get done.

[Here's a great piece from The Chronicle of Higher Education about teaching students time management skills.]

I saw that one student had scheduled in “Unwinding/Writing time” at the end of the day. That got me thinking. “Do you guys see writing time as chilling out time?”

Some said yes. They don’t seem to have any trouble getting their words done each week. Because they find it pleasurable (mostly). One student said that many students in her math lecture keep laptops open and browse social media during class; she, on the other hand, writes her novel. I’m not sure what to say about that. Yay! or Don’t!

Some said no, writing time and chilling out time are not the same thing. These are the folks who do have trouble getting their words done each week. Because it’s not pleasurable, or not always pleasurable. (I am in this group.)

I told them, if you are the latter, then you can’t lump “writing time” into “personal time.” Because you’ll procrastinate. Or you’ll wait to write until the end of the day when you’re time and need a real break–not an activity that’s going to mentally (and maybe even emotionally) tax you.

My students wished that I’d had them fill out an activity log at the beginning of the semester. Next term, I will. There are a few good time management resources on the Dartmouth website (although some are a little dated).

Next time, I’m going to talk about the “Eisenhower Method” of time management and draw this figure on the board.

Next time, I’m going to talk about the “Eisenhower Method” of time management and draw this figure on the board.

According to this article, you should spend 80% of your time doing the things that are Important, but Not Urgent, and the other 20% of your time divided among the other quadrants (with as little time as possible devoted to the time-wasters of Not Important and Not Urgent).

Wow. When I apply that ratio to my Activity Log from last week, I can see that my ratio was exactly the opposite: the majority of my time was devoted to urgent deadlines.

Most creative writing classes have periodic due dates, like most college classes. A paper or project due every few weeks or so. The task hangs out in Important but Not Urgent quadrant until the day or two before the deadline, when all ones time is devoted to the urgency of the deadline.

With Weekly Words, however, I force them to put their writing time into the Important and Urgent quadrant every single week for ten weeks. And force myself to think of it this way, too.

I told my students that famous quote attributed to Lawrence Kasdan:

“Being a writer is like having homework every day for the rest of your life.”

That got their attention.

I told my students to think about their parents, about the kind of home they grew up in. Whether we like it or not, we wind up using time very much like our parents and grandparents did. I’m from a working class family, which means I grew up in a culture where my day was structured by the dinner bell, the lunch whistle, the time clock.

It’s been a great challenge in my life to be the boss of my own days.

Reflections and Observations

Here are a few things I’ve been thinking about since my post last week, and thanks to those of you who have commented, too.

I can’t just write on the weekends. I’ve got to write a little during the week. I’ve got to keep my head in my novel as often as possible.

I’ve got to stop answering emails first thing in the morning. I must use that time to write. I must resist The Borg.

So often I’m communicating when I should be writing, plugged into the hive mind when I should be unplugged as much as possible. I believe that we should devote our best time of day to our writing. For me, that’s the morning.

I’ve got to stop checking email and social media when I’m engaged in class preparation and novel writing. It causes constant interruptions, the introduction of Not Important but Urgent (or not Urgent) distractions into my day. Also, checking for notifications and new emails makes everything I do take twice as long.

I’m glad I counted my writing time as work hours, not personal time. This was not always so. Sixteen hours of writing in one week is actually a lot for me; it happened b/c of the P&T deadline. During the school year, I’d say I write for about five hours a week, usually on the weekends. During the summer, I write (or research) for about five hours a day.

The price I pay for long blocks of time to write on the weekend are long weekdays. On Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesdays, I work from the moment I get up to about an hour before I go to bed. Those days are 13 or 14 hours long.

Email is killing me

I’ve got to get better at email. In the Harford article I linked to last week, he says there are only five things you can do with an email:

delete it

delegate it

reply to it

defer it

take some more substantial action.

It’s all I can do during the week to take care of #1 and #2 type messages, the Important and Urgent ones. I can sometimes take care of #3 type messages if all that’s required is a quick answer. But if you notice my Friday, I spent about 3 hours answering all the #3, #4, and #5 emails that had come in during the week. I’ve learned the hard way not answer important emails after 8 PM, so I leave #3, #4, and #5 type messages until morning. But: if I get up and write, that further delays my answers.

Ben Percy once gave me a great piece of advice about my email problem: he said that I should treat those messages like old fashioned letters. If a colleague sent me a letter asking if I had any ideas about campus speakers, or an old friend sent me a long catch-up letter, or an acquaintance asked for some professional advice, would I drop everything and write a letter back? No, he said. I should get my writing done for the day, and then think about replying.

The problem, of course, is that some of those messages waiting really do need a prompt response. And I’m not just talking about messages from frantic students either. I’m talking about colleagues and friends.

I’m going to start imagining that I am my doctor. I would never expect an answer from her (via her nurse) to a routine medical question outside of business hours or on the weekend. Doctors and lawyers, I’ve noticed, have excellent professional boundaries, and people respect those boundaries.

This Blog and My Time

Realization: If I want to get writing done during the week and not just on the weekends, I either need to

wake up earlier and write for awhile before entering The Borg

take care of The Borg throughout the day or in the evening

leave or limit The Borg

I think about C a lot.

I think about the fact that I’ve spent an hour on this blog post thus far this morning. Yes, I have benefitted from writing this post. This blog in general has forced me to be reflect on things I never would have reflected on otherwise. It’s been good for me personally and professionally. And maybe it’s been good for you, too.

But are these words getting my novel written?

No.

Thanks for reading this blog post, everyone. It felt Important and Urgent to me to get these thoughts out before moving on to other topics here at the Big Thing. Now, I’m going work on my Weekly Words for my novel. It’s Important and Urgent, too.

October 16, 2013

Dinty Moore on the advantages of the MA (not just the MFA) in Creative Writing

On October 15, the awesome human being who is Dinty Moore said the following on Facebook. He shared it with his network of friends (a small legion!) and in a few groups to which he belongs.

On October 15, the awesome human being who is Dinty Moore said the following on Facebook. He shared it with his network of friends (a small legion!) and in a few groups to which he belongs.

It’s really great advice for undergrads and their writing mentors who are in the midst of MFA Admissions Season.

I’ve reproduced it here with his permission.

An Open Letter to My Many Friends Who Teach Creative Writing to Undergraduates:

Many writing teachers still advise their undergraduate students that they “may as well go for an MFA because an MA doesn’t qualify you for anything.” Well, that makes sense for some students, but not all of them, especially now with the growth in the degree. So, we’d like to offer:

Five Good Reasons to Suggest an MA (Yes, an MA) to Your Students

1 With competition to enter MFA programs increasing at such an unprecedented rate, many students are coming up blank when they first apply. A younger student might not be ready for a top MFA program and may be wasting time and money applying (for now.)

2 The MA path, though, allows an extra two years to focus on enhancing a writing portfolio. A hard-working student can write a lot of poems, stories, and essays in two years. If they still want that top MFA program, their chances have greatly improved.

3 Here at Ohio University, those two years come with generous graduate assistant teaching stipends, excellent travel funding, and close faculty mentoring. In other words, time to write, teaching experience, and no student loans necessary (if the student is frugal).

4 For a student considering the PhD in creative writing as the ultimate goal, the MA could be a better path. Our MA students take graduate literature seminars and training in rhetoric and composition in addition to their workshop courses, and have had excellent success pursuing doctoral studies.

5 Even if the student doesn’t intend to pursue a degree beyond the MA, two years of focused study, workshop, and mentoring on poems, stories, or essays will make the student a stronger writer, reader, and thinker.

So please suggest the MA to your students, especially those with potential but perhaps a need to develop a bit further along the way.

Visit http://www.english.ohiou.edu/cw/ for further information, or email Dinty W. Moore at moored4@ohio.edu.

Cathy’s Thoughts

I teach in an MA program in Creative Writing as well. You can find out more about it here.

One thing I like about our program is that students DON’T specialize in a genre. They’re required to choose from a menu of workshops:

Fiction (me and Sean Lovelace)

Poetry (Mark Neely)

Creative Nonfiction (Jill Christman)

and Screenwriting, too! (Matt Mullins)

I’ve got a few good reasons, too

1. An MA will give you time to figure out what genre you are–if you’re unsure. And you pretty much HAVE to know when you apply to MFA programs, which are completely taxonomical by genre track.

2. An MA gives you some time to mature. Right out of college, I applied to 10 MFA programs and was only accepted at two–and one of those with no funding. Given how many programs did not accept me, a few years writing on my own and/or an MA program would have given me and my work time to mature.

3. Completing an MA demonstrates that you really are ready for graduate study. As someone who used to teach in an MFA program, I can tell you that if I’m looking at two candidates, and their writing samples are about the same, and one has an MA under their belt–well, that says a lot about their ability to do well in an MFA program.

If you know of a great MA program in CW, please include a link to it in the comments!

October 15, 2013

The Day Cole Porter Died

Photo by Don Hunstein.

Cole Porter died on October 15, 1964 in Santa Monica, CA.

Reportedly, his last words were, “I don’t know how I did it.”

The picture I’ve selected isn’t one where he’s smiling. That’s because his last years were pretty bleak, honestly. Not long after this picture was taken, the leg that had given him pain for over 20 years was finally amputated.

And he never wrote another song.

Around the time that this photograph was taken, he was writing what would end up being his very last song called “Wouldn’t it Be Fun?” You can read the lyrics here, if you like. But they might make you cry.

I think it’s the saddest song he ever wrote.

What’s your favorite Cole Porter tune?

(Next week, I’ll finish up my “Do the Math” series of posts about time management, but today, I wanted to take a moment to remember the death of my fellow Peruvian.)

October 8, 2013

Do the Math: Part 2

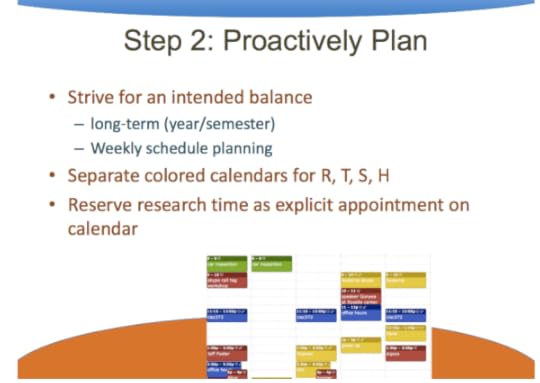

Last week, I talked about “doing the math” (and by extension time management) here at The Big Thing. This powerpoint contained a slide that got my attention.

I use Google Calendar to schedule meetings and appointments, but not writing time, teaching time, etc. I don’t compartmentalize my day that way–although maybe I should. My novel writing students and I were talking about time–how there’s never enough time to work on novels–so I showed them the picture and said, “C’mon. Let’s log in how we spend our time for one week.”

I went first.

How do I spend my time? I was already asking myself that question a lot because my P&T document and materials were due this past Friday.

FYI: “P&T” stands for Promotion and Tenure. It’s basically a résumé, and the supporting materials (i.e. evidence) is organized however your institution prefers: binders, folders, hanging-file crates. (Here is an example of a P&T vita I found on the Ohio State English Department’s website, for example). For P&T, I divide my job as a university professor into three categories and account for my activity in three categories:

Scholarship: publication, grants, readings, public appearances, the “writer me”

Teaching: in class, in office hours, grading, thesis supervision, class prep, the “teacher me”

Service: committee work (in my area, my department, my college, and my university), service to my profession, mentoring students, the “citizen me”

You can click on this calendar to see it more closely. And find out when I take showers.

How I spent my time last week. Roughly.

Key to My Activity Calendar

White = Scholarship: I’m working on a novel, and I wanted to get all the pages I’ve written over the last two years compiled into one document to share with my husband and my P&T committee. I wrote about 2000 new words last week as I pulled it all together, plus made lots of tweaks to all 294 pages. Also, I carved out time for the keynote address I’m delivering this Thursday at the 2013 Indiana College English Association conference.

Green = Teaching: I’m teaching three courses this semester, three separate preps, one graduate course and two undergrad. I taught two books this past week (A Visit from the Goon Squad and the last third of Julianna Baggott’s Pure). I’ve read them before, but I needed to refresh my memory. My undergrads take a quiz every time they read something for class, which I must grade. I also graded and gave feedback on six student blog posts and 10 four-page writing assignments. I met with students during office hours, etc.

Red = Service: I spent a lot of time on the P&T document and materials. I’m also on the College Curriculum Committee (CCC) which meets on Mondays, and we had a CW area meeting this week, too. I also spent some time writing letters of recommendation for former students.

Blue = Communication: The truth is that, if I’m using my computer, I’m usually checking email and social media at least once an hour, if not more. In a sense, I’m communicating all the time. Emails. Social Media. Posting to my blogs or replying to comments on those posts. But this category denotes time in which I’m not multitasking, but rather spending dedicated time taking care of communication.

[Last week, I read this great post, "Ten Email Commandments," which made me realize (among other things) that I use my various inboxes as "to-do" lists, which explains why, when you send me a message on FB asking me to do something, I often forget that you asked me, because FB messages aren't visible like email messages are.]

Yellow = Personal time. It’s kind of sad when you have to count “showering” and “eating dinner” as “personal time,” but it’s true.

Totals

Gulp. I worked 72 hours last week.

I have avoided adding up this figure for days. Ever since I made the calendar, I have avoided tallying it all up. I didn’t want to confront the fact that I worked 72 hours last week. My husband just came into the room, and I said, I worked 72 hours last week! And he said, “Uh-huh.” He’s not surprised.

That time was divided thusly:

Scholarship = about 16 hours

Teaching = about 24 hours

Service = about 21 hours

Communication = about 11 hours

Suggested Reading

As I worked on my activity calendar this week, these articles were published about how we spend our time in academia and/or online. How appropriate!

Adjuncts Should Do as Little Work as Possible

Essay Documenting what a Faculty Member Does in the Summer

“If You Want to Be My Student”

Michelle Filgate on quitting Twitter for a week

Reflections

I don’t want to hear oh how dedicated I must be, blah blah blah. Because the truth is that while I was working on my novel this week, and prepping for classes, and reading course proposals for CCC, I was also letting myself get sucked into checking messages and reading stuff on the internet. I mean, MY GOVERNMENT SHUT DOWN LAST WEEK. People were lighting themselves on fire. I found time to tweet at my congressman every hour for an entire day. I found time to order pictures of my new nephew and text my mom about my dad’s birthday.

By sharing my week with you, I’m not trying to set myself up as some kind of ideal. In fact, I’m sort of horrified about this. I’m full of questions.

Was it necessary to have worked that many hours?

Are those hours completely misleading since I was online most of the time? If I spent 11 hours doing pure “communication,” plus I was online a great deal during the rest of the time, how much time did I spend online?

Is this a situation of my own making, or is it a situation all academics are facing these days: a work week that bleeds into our evenings and weekends? Why is it bleeding? Is it our fault, or is it the job’s fault?

If this was 1993, not 2013, and all other circumstances were the same, would I still have “worked” 72 hours this week?

Do you count the time you spend writing as part of your work week? If not, why don’t you? Because you absolutely should–although, yes, I know, it’s especially hard from the middle of the semester onward.

Stay tuned, dear readers, until next week. I have more to say. [This post was actually twice as long, so I turned it into two. ]

Why don’t you keep an activity log this week too? The more the merrier. Or the more depressed.

October 1, 2013

Teaching Tuesday: Do the Math

I’m sort of nervous about this post. Let’s see how it goes.

I’m sort of nervous about this post. Let’s see how it goes.

It’s incredibly difficult to gauge how much work to assign students and how much work to give yourself. I think you have to be in a place for at least a year or more to get it right.

Here are some things you can do to avoid mid-semester meltdowns.

Ask to see a sampling of syllabi of the classes you teach; how much work do others generally assign? If they’ve been there for awhile, they probably know what works.

Are you teaching on quarters or semesters? Are the courses 4 credits or 3 credits?

Ask how many classes students generally take a semester. If they take four a term, your course will probably need to be a little more rigorous than if they take five or six a term.

Are they on the quarter or semester system? How many students will be in your classes?

Anecdote

My hardest semester of teaching was my first semester in my first full time job. I went from teaching four classes a semester (eight classes a year) to teaching three courses a quarter (nine a year). I also went from teaching 15 students a section to 25.

I made two mistakes.

I crammed my semester syllabi into quarters.

I tried to I to do for 25 students what I’d been doing for 15, and I almost died.

Think like a lawyer.

Imagine you’re a lawyer and keep track of your billable hours. The typical college professor puts in 50 to 70 hours a week, so let’s be conservative and say you’re going to work 55 hours a week. (I work more than that.) That’s over nine hours a day, six days a week. Remember that for a college professor, “work” is R, T, S:

Research/Writing

Teaching

Service

Strive for a R/T/S ratio of, let’s say, 30/60/10.

[Where did I get this number, 30/60/10? Why not 40/55/5? The ratio varies depending on the institution, and it's a good idea to ask your colleagues what they think the ratio is vs. what the institution believes it to be. Here's a great link that talks about this. ]

Research 30% of 55 hours 16.5 hours a week 2.75 hours a day

Teaching 60% of 55 hours 33 hours a week 5.5 hours a day

Service 10% of 55 hours 5.5 hours a week less than an hour a day

I hope this breakdown is clarifying to you. It should be.

Over the course of my career, I’ve had a variety of teaching loads.

4/4

3/3/3

3/3

3/2

2/2

I’m very glad that I spent two years as a non-tenure track instructor. Once you have a 4/4, you understand how to make the best use of the others. Because, you see, my ratio applies no matter your load, which means–ideally–you’re supposed to spend approximately 33 hours a week on your teaching no matter what your load is.

Talking to Myself

I remember the first time I did the math. It was that horrible semester when I was teaching a 3/3/3 with 25 students per class, and I was dying. Here’s an approximation of the conversation I had with myself.

You’re doing for 25 at College B what you used to do for 15 at College A.

I need to give the students at College B my best.

You need to give them what College B is paying you to give them.

You’re saying I should give these students less than my very best?

No, you should always do the very best you can within that 33-hour time frame. Find other ways to teach well. There are other ways to be an effective teacher of writing without writing a freaking treatise on every single paper or story or poem.

But what about these kids! Don’t they deserve more than that?

Whether or not they knew this consciously or not, your students chose to go to College B, which devotes fewer resources to writing instruction than College A did. It’s not your job to give the students at College B the exact same quality instruction as College A, because this can only be achieved at the cost of your writing time (which is limited) and your personal life (which you need to try harder to have).

You’re telling me to be a shitty teacher.

No, I’m telling you to be a more resourceful and effective and healthy teacher.

You’re saying that students at College B don’t deserve what students at College A get.

Oh, no. Everyone deserves the very best they can get. A great young writer is just as likely to emerge from College B as from College A. The difference is that all students who go to College A will probably get more personalized feedback on their writing, will probably produce more pages, because their instructor has a 2/2 with 15 students per class while you’re at College B with a 3/3/3 at 15/25/25 students per class.

This sucks.

Yes, it does. There’s nothing more important than learning how to write effectively, and schools talk a good game about “rigor,” but there’s only one way to ensure every student leaves college having learned how to write well: classes capped as small as possible, and experienced, well-compensated instructors teaching as few classes as possible, all of which is really, really expensive.

We’re doomed.

Stop it. No we’re not. Just do the best you can and take care of yourself.

September 24, 2013

Teaching Tuesday: Setting

This week in my novel-writing class, we’re talking about setting. This is the lecture I’ve developed over the years to talk about this subject, which is near and dear to my heart. Midwesterners especially leave setting out of their stories, but we very much need them not to.

Let’s begin

“You have to have somewhere to start from: then you begin to learn,” [Sherwood Anderson] told me. “It don’t matter where it was, just so you remember it and ain’t ashamed of it. Because one place to start from is just as important as any other. You’re a country boy; all you know is that little patch up there in Mississippi where you started from.”

–William Faulkner

Illustration #1

Many apprentice writers write what I call the “Nowhere and Everywhere Story.” Their stories occur in a temporal and cultural vacuum. The setting could just as easily be a small town in Pennsylvania as a small town in Florida, a suburb of Los Angeles as a suburb of New York City, a farm in Oregon as a farm in Ohio.

Most of the time, it’s because they assume that the setting in their head

is on the page already

that (since oftentimes the students in workshop are from the same state) its understood that the story is set in the kind of place they are from

(gulp!) they claim they omitted setting on purpose, since one place is just like any other place.

I wasn’t immune to this problem. I lived the first 21 years of my life in Indiana. I assumed (without really meaning to assume) that the rest of the world was just like Indiana, and my first stories could have been set anywhere, too.

I always try to get my creative writing students to focus on setting, but I often get blank looks. It’s like asking a fish to talk about the water in which it swims. What are you talking about? the fish says. It’s just the world, ya know?

The only way the fish can possibly describe the water it swims in every day, all day, is to remove it from the water—and then put it back.

Or another analogy: living your life is like listening to an LP record. If someone asks, What do you hear? you would describe the music only. You wouldn’t describe the sound underneath the music, the little hisses and pops the needle makes. Maybe you don’t even hear those hisses and pops anymore; you’ve learned to tune them out.

But, if you become a writer, you have to train yourself to largely ignore the music that most people consider “life” and focus instead on the hisses and pops underneath. Nowhere and everywhere must become somewhere.

Illustration #2

“Every story would be another story and unrecognizable if you took up its characters and plot and made it happen somewhere else … Fiction depends for its life on place. Place is the crossroads of circumstance, the proving ground of What happened? Who’s here? Who’s coming?”

— Eudora Welty

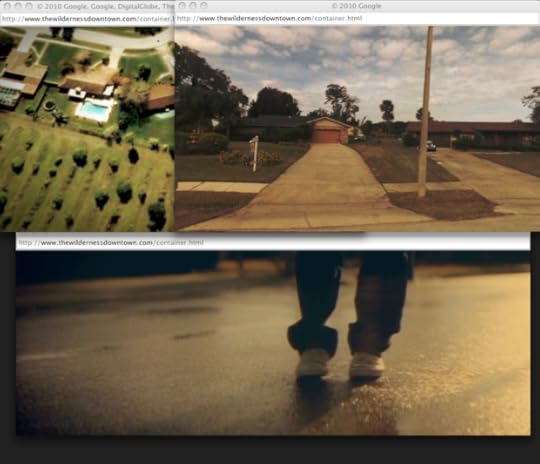

I like to begin my in-class discussion of setting with this photograph.

Do you feel anything when you look at that photograph? I ask.

No, my students say.

I wouldn’t expect you to.

Okay, now, if you’ve got a computer with you, go to this website:

http://thewildernessdowntown.com/

Plug in the address of the house you grew up in, or the name of your high school.

Then we watch what happens when our hometown magically shows up in an Arcade Fire video for the song “Wilderness Downtown.”

That’s when I tell them that that aerial photograph is of my hometown, my high school specifically, and even from above, even though I haven’t lived in that town for a long, long time, that picture fills me with many emotions.

I say to them: When you were watching your own videos, I saw that they were all a little different. Some of you were looking at suburban gated communities. Some of you were looking at farmland. Some of you were looking at apartment buildings along busy roads.

But if I said, tell me about home, you might have neglected to mention those differences. You might have assumed that the picture of ‘home’ in your head is the same as the picture in mine, but it’s not.

When you saw those streets, those houses, those buildings on your screen, you felt things. You felt homesick or anxiety or fear or hatred or nostalgia. That’s what you have to do as writers. It’s not just about showing the reader a particular exterior landscape. It’s about giving them a particular interior landscape too.

The reader is that figure in tennis shoes and a hoodie running down the street you’ve created, and you’re not just saying This is what this street looks like, you’re saying This is what this street feels like.

Illustration #3

In 2012, I met the writer J.T. Dutton at the Midwest Writers Workshop, and she taught a great session on setting. She’s the author of two young adult novels and teaches at Hiram College at the Lindsay Crane Center for Writing and Literature.

I’ve been using this handout, Setting as Character by JT Dutton, for two years, and it never fails to elicit great material from my students.

She’s very graciously offered to share it with us here at the Big Thing.

HERE IS NOT THERE, OR SETTING AS CHARACTER by JT DUTTON

20 interesting questions to ask yourself as you create the setting of your novel

How big or small is the place you want to write about? What is the size of the population?

Where is it located in relation to other landmarks, regions, or worlds?

What is the landscape like? Is it mountainous or flat? A prairie or desert? What grows there?

What is the average temperature? Do the seasons change? Does temperature or weather affect how people live and dress? Or how much time they spend outside?

How do people earn a living? Who is the largest employer? How much time to people spend working each day?

What is the average income? Are people in his place unusually poor, or unusually well off?

Who has the power to create change? How is this place governed?

What are the conflicts between neighbor and neighbor? Is there stratification? Envy or hatred between groups?

Who is happiest about having to live/be in this place? Who is least happy?

If the place held an annual celebration, what would it honor? What makes the people of the town most proud? Who marches in their parade?

How “modern” is it in comparison to the world around it? Is it behind the times? Or does it have its finger on the pulse of fads and fashions? Do the people here look up or down at any other place?

How clean or safe is it? Do people feel comfortable about leaving their doors unlocked, or does it have an eeriness or grittiness?

Who is happiest about living or being in this place? who is least happy?

How moral is it? Do bad people suffer and good people triumph? Or are endings determined by abstract and complicated forces?

What religion do most people who live here practice? Are residents bound by a certain kind of spirituality?

What is this place’s biggest flaw in the eyes of a stranger? What is its biggest asset in the eyes of a stranger?

What is the mood of this place? Is it spooky? Bright? Honest and comfortable? Sad?

What is the biggest threat to peace and prosperity?

How vulnerable is this place to change? How sheltered or unsheltered is it?

Who best represents the town’s image?

There are about a million more things I could say about setting, but I’ll stop there.

September 17, 2013

Teaching Tuesday: Requiring Students to Blog about the Class

This semester, I’m teaching a grad course on the linked stories form and an undergraduate course on the novel form.

This semester, I’m teaching a grad course on the linked stories form and an undergraduate course on the novel form.

These past two weeks, in both classes, we’ve been talking about subplots, layers, and throughlines.

My students have been doing an excellent job of sharing their notes on our course blogs.

Each week, I select one student to be our class “scribe.” They turn their notes from class (lecture + discussion + personal anecdotes/flavor) into a class “report.”

And I grade it.

Here are a few samples.

Jen Banning on how you can turn stories into a novel.

Kelsey Englert on how you can turn a novel into stories.

Kate Gutheil also on turning a novel into stories.

Rebecca B. on subplots in novels.

What I’ve learned

I feel like it’s only fair to share my course content (to a certain extent), since most of my course content in novel-writing comes from materials I’ve been able to find online.

I made my students contributors to these course blogs, which means they format their posts, and I check them over and publish them. Or they can publish them on their own blogs and I reblog them.

I love how the practice of students blogging about the course enables me to see their notes, what they learned, what made an impression (and what didn’t).

I encourage them to post on their own blog (like Kelsey E. did). What better time to start a blog than when you’re in school and you’re immersed in books and writing? If you like what some of them have to say, feel free to follow them back to their blogs or just say, “Good job” or “Thank you.”

Some of them, however, aren’t yet comfortable with having an online presence. And that’s okay, too.

I’ve been trying to figure out for the last few years how to incorporate the social media practices of literary citizenship into my courses, and I think I may have finally figured it out. Here is the rubric I use to assess/grade their blog posts, which are worth 10% of their grade:

Yes, I know this is a certain kind of blogging–that’s being graded by the professor–and so the students probably aren’t going to talk smack about me or the material. As if that’s what blogging is anyway.

So many people think blogging is about bragging. It’s not. To me, blogging is teaching. It’s sharing. And what better way to engage in that process than to blog about a class you’re taking, esp. when you have the professor’s permission to do so.

I came up with this idea after teaching at a few writer’s conferences and festivals. Many of the attendees shared what they learned from me. I wondered: why shouldn’t I encourage my college students to do what is de rigueur at conferences?

One reason why I do this: knowing how to blog is a marketable skill. My former student Ashley Ford works for Pivot Marketing in Indianapolis and here’s a blog post about blogging, also known as “sponsored posts.”

September 11, 2013

BSU + MWW: or “How I Spent My Summer Vacation”

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again:

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again:

Did you know there’s a writers’ conference in Muncie, Indiana?

Did you know that Veronica Roth, author of the best-selling dystopian YA novel Divergent found her agent at this conference in 2009?

Well, now you do.

This conference is called the Midwest Writers Workshop, a yearly gathering of agents, editors, and publishing professionals whose mission is to help people become published authors.

Basically, MWW brings New York publishing to Muncie, Indiana, and this year, the conference celebrated its 40th year with 238 people in attendance from 20 states.

Watch this video and see for yourself how awesome it is.

As soon as I found out about the conference, I started thinking: How can I bring MWW and BSU together?

Answer: apply for a grant through the Discovery Group. Thanks to this amazing organization, many Ball State students (all of the English majors or minors) were able to attend this year’s conference as paid interns and scholarship winners.

The Scholarship Winners

These students applied for scholarships to attend the conference, a $250 value. They were selected by the creative writing faculty based on a writing sample and essay. They attended two days of panels, presentations, and talks by industry professionals.

Jessie Fudge

Adam Gulla

Rianne Hall

Alisha Layman

Logan Mason

Brittany Means

Tara Olivero

Chase Stanley

Some of the scholarship recipients have taken my novel-writing course, where they learned the basics of the publishing process. I was happy some of them signed up for a pitch sessions and that my former students Alisha Layman and Jessie Fudge were successful in piquing the interest of agents about novels they began in my course.

Junior Brittany Means received the award for best poetry manuscript submitted, as well as for best overall manuscript (the R. Karl Largent Writing Award) and a $200 cash award. This is even more significant when you consider that Brittany wasn’t selected as the best student writer at the conference, but rather the best writer. Period.

The moment Brittany Means found out whe won the Karl Largent Award

The Interns, aka “Social Media Ninjas”

These students worked as tech assistants, social media tutors, and agent assistants. They got a rare glimpse of the publishing industry, gained real-world experience, and built credentials that will give them an advantage in their careers.

Here’s what they did (and please click on the hyperlinks to read the Storify for each day of the conference!):

Students worked alongside faculty in two all-day “tech intensives. One helped attendees learn how to create and format an e-book (taught by editor Jane Friedman), and the other helped them build an author website (taught by writer and editor Roxane Gay). I wrote about the tech intensives in more detail here.

The interns also served as buzzers in a fun game of Literary Jeopardy.

Day 2 & Day 3 : Helping the Attendees and the Literary Agents

During “Part II” of the conference, the interns were split into two teams.

Six students worked as Social Media Tutors.

Mo Smith

John Carter

Madison Jones

Rebekah Hobbs

Kameron McBride

Jackson Eflin

Everyone who attended Midwest Writers had the opportunity to schedule a free, 50-minute social media consulting session. This is what it looked like. In advance of the conference, the tutors studied their clients’ current online presence and made recommendations about how they could be better online literary citizens. In two days, students met with over 50 clients.

Five students worked as Agent Assistants.

Rachael Heffner

Sarah Hollowell

Becca Jackson

Kiley Neal

Sara Rae Rust

Each agent heard approximately 30 three-minute pitches. In advance of the conference, the assistants coordinated schedules, communicating with the literary agents and the attendees. At the conference, they handled last-minute changes to the agents’ schedules.

All students had a chance to spend an hour and a half talking to literary agent Brooks Sherman. The conversation ranged from careers to publishing trends.

All the interns got a chance to pick the brain of a NY literary agent.

The Final Verdict: “Awesome”

Intern Sarah Hollowell said it best. “Here’s what I took away from #mww13: I am meant to be in this community.”