Cathy Day's Blog, page 3

February 8, 2016

Five Things: 2/8/16

So far, what I like most about this residency is how anti-social you’re allowed to be. You can behave in ways that would be taken as rude under almost any other circumstance. Let’s say I leave my computer to walk into the kitchen to make a cup of tea and I’m still thinking about what I’m writing and I find that someone is already there. She’s absorbed in a book while she eats some cereal, doesn’t say hello how did you sleep are you have a good day how’s the writing going? She smiles and returns to her book. I can make myself a cup of tea and walk right out of that kitchen. Or I’m eating dinner with everyone at 6:30 PM, the only time of the day we all come together and eat a nice meal prepared by Chef Linda, served buffet style. It’s sort of like going to a dinner party every night, except you get to wear sweats and slippers if you want to. So, I’m at this dinner party in my slippers talking to the guy sitting across from me about, I dunno, the Lusitania or football or ice cream, and when he’s done eating, he stands up and says, “Back to work,” and I say bye and that’s that. No long goodbyes. No hard feelings. Everyone understands. If only real life could be this way!

2. My space.

“The Beach Room.” Not sure why it’s called that except that there is a large conch shell on my desk.

“The Beach Room.” Not sure why it’s called that except that there is a large conch shell on my desk.This is a picture of my room at Ragdale, although I had to move the twin bed against the wall because I kept waking up terrified I was going to fall out.

How long has it been since I slept in a twin bed? College, I think.

Studio with skylights!

Studio with skylights!And here’s a picture of the studio they gave me, too, so that I can storyboard my novel on the nice white walls.

3. Things I worry about even though I shouldn’t.

A great essay I read this week: “Children of the Century” in the New Republic. Alexander Chee asks the question, “Can a historical novel also function as serious literature?”

Jesus, I hope so.

When I tell people I’m writing a book about Linda Lee Thomas Porter, long-time wife of Cole Porter, I get one of two reactions: 1.) Oooh, I love books like that. 2.) Oh, I didn’t realize you were writing a book like that. Re: #2, by “like that,” they mean what we’ve come to think of as “the wife book,” the “woman behind the man book” like: Loving Frank by Nancy Horan, The Paris Wife by Paula McClain, etc. Why don’t the #2s think that I’m writing a book like The Women by T.C. Boyle, Ragtime by E.L. Doctorow, or Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel? Is it because I am a woman writer or because I’m writing about a female character? Or both? The second set of books are also novels about real people and real events, what I like to call nonfictional fiction, but they were all written by men or have primarily male characters.

Sometimes, as I’m writing a scene or making a decision in my novel, I find myself thinking about how that decision will affect the way the book will be presented to the world–commercial or serious? genre or literary? “male” or “female”?–when what I need to do is just write the damn thing the best way I know how and let my agent (whom I trust) guide me. Every single day, I get anxious about this, especially now as I come closer to finishing, but then I tell myself its useless to borrow worry. Reading an essay like Chee’s reassured me that I’m not the only writer who worries about these matters. Note to self: keep working on my essays related to the subject of my novel and pitch them to The Atlantic and The New Republic; this definitely sends a message about how you want to be read.

4. Nonfictional fiction.

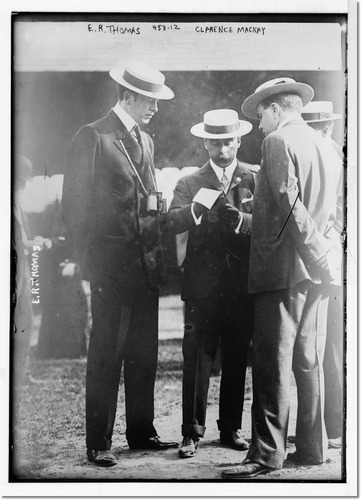

Linda’s first husband, E.R. Thomas, hanging out with Clarence Mackay, the guy in the middle with the enormous mustache.

Linda’s first husband, E.R. Thomas, hanging out with Clarence Mackay, the guy in the middle with the enormous mustache.Most of the characters in my novel are based on real people: Linda, of course, and Edith Wharton, Emily Post, Bernard Berenson, Elsie de Wolfe, Bessie Marbury, Anne Morgan, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon.

Today, I’m working on a chapter in which Linda is being courted by Clarence Mackay.

The book that gave me permission to write my novel the way I want to write it is Ragtime by E.L. Doctorow. Which features real historical figures like Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, Harry K. Thaw, Emma Goldman, Harry Houdini, and J.P. Morgan, alongside purely fictional characters. There’s one scene in particular in which Gilded Age “It Girl” Nesbit goes to a socialist meeting where Emma Goldman is speaking and then ends up taking off her corset and allowing herself to be massaged by Goldman.

Now, this never happened. And once I reminded myself that I wasn’t writing a biography, that I could invent, the book started to flow.

5. “altgenres”

And speaking of genres and subgenres and labels, another great read from this week was this article from last month’s Atlantic, “How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood.” Believe it or not, this article got me going on a essay about “selling” the English major, the humanities, and a liberal arts education. Stay tuned…

The post Five Things: 2/8/16 appeared first on Cathy Day.

February 1, 2016

Five Things: 2/1/16

1.

I want to thank my friend Gail Werner for recommending that I read Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic, which came to me–as many books do–right when I needed it most. I’ve never read Eat Pray Love. I didn’t watch her TED talk on creativity (where Big Magic got started), even though lots of people were sharing it on Facebook for awhile, singing its praises. Why didn’t I? Why not read her wildly popular book or see what she had to say? Well, because I knew that a lot of writers I admire didn’t like Gilbert much–as a writer, and/or as a cultural phenomenon–and I really, really wanted them to consider me a good, serious, “important” writer. Of course, I wasn’t thinking any of this consciously. I was unconsciously “pandering,” similar to what Claire Vaye Watkins talked about in this provocative essay which came out a few months ago. Every time I think I’ve stopped “pandering,” something comes along to make me realize that I still am. Man, this shit runs deep in me. In all of us, I think. The older I get, the more I realize that the high school lunchroom mentality never leaves us. Even though I didn’t mind not sitting at the cool kids’ table in high school, I still aspired to it–just in a different lunchroom.

2.

The first month of my sabbatical is over, and I’m happy with the progress I’ve made thus far. I have some self-imposed deadlines: finish the current section by the end of January, finish the next section during February, the last section in March, revise in April. I write every day–at least two pages, sometimes five or six. The manuscript is currently at 400+ pages, and at this rate, might get to about 600 pages, but I don’t think it’s going to end up that long. I’ve been writing very scenically, dramatizing much of the novel in something akin to “real time.” This would be fine if the novel’s “clock” was a month, a year, or even a few years. But the novel covers about 20 years. I wanted to “see” the scenes in my imagination and show them on the page, but now that I know what happens, I plan to go back in and do more summarizing, more telling, which is what I really prefer doing anyway.

3.

I’ve been reading a lot of young adult novels over the last few years. Almost all of them take place over a relatively short period of time and are quite “scenic,” unfolding at a rate of, say, one day or maybe one week represented by one chapter. That’s something I’ve been trying to teach myself how to do better–create a “faster read” by slowing way, way down, create a vivid and continuous fictional dream. Novels need scenes. Novel readers need moments when they can just be “in the story.” But frankly, I get a little bored after a while with this approach–both as a reader and a writer. Another book I read recently was the marvelous Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff. This book covers a lot of time, and certainly, there are dramatized scenes, but lots of skillful telling, too. I remember one chapter in particular that needed to cover the first 10+ years of a couple’s marriage. Groff did so by focusing just on the parties they threw in their apartment. The style of party changes over time. The main characters change. Their friends mature. Think about how some of the montages in Groundhog Day work–Bill Murray figuring out how to play piano, how to woo Andi McDowell, etc. The thing I have to figure out, I guess, is how much of what I’ve written needs to be “in scene” and how much needs to be montage.

4.

At the same time that I’m thinking about shortening/tightening the chapters I’ve already written (a process I really look forward to), I’m also trying to draft brand new chapters (a process I dread). I love to edit, but I do not love generating new stuff. Here’s how I’m learning to cope with this: I think of each new chapter like a painting. An oil painting in particular, which is created in layers. First, I sketch. I write about the scenes rather than writing scenes. I free write as things come to me. Then I move things around. Decide on the beats of the chapter. I try not to get bogged down in details like what my characters are wearing or their expressions or what kind of couch they’re sitting on. Sometimes those details come first in my mind, and I build around them, but most of the time, they come last. I use this a lot: xxxx. Reminding myself to come back later and fill in the blank rather than get sidetracked with research–and boy, is it tempting. Every day, I try to add another layer, another level of detail to my painting. Let’s say that my chapter/painting’s not done until I complete 10 layers. Maybe I’m still too much of story writer, and I should move onto the next chapter after I finish step 5, but I like the feeling of accomplishment that comes with getting to about step 7 or 8. I love the feeling of “finishing” a chapter. I usually take a day off and do something physical, and then I start the next chapter and remind myself (again) not to fuss with the first sentence, the first paragraph, but to just start sketching.

5.

Today, I’m heading to Lake Forest, IL to do a residency at Ragdale. Eighteen days. I’ve never done a residency before. I think I was always afraid that I’d get to one of those places and not be able to write. I also thought that it was kind of silly to go somewhere to write when I live in a relatively quiet house with no kids. I even have a husband who does all the cooking! So why do a residency? But my friends swear by them, and I think it will be good to separate myself from the allure/distractions of my home, my yard, my dog, my cats, my neighborhood, my job, my husband. I’ll let you know next week how it’s going. Here’s a nice video about Ragdale, what it looks like, etc. In the summer of course!

The post Five Things: 2/1/16 appeared first on Cathy Day.

January 25, 2016

Five Things: 1/25/2016

For a long time, I enjoyed reading my friend Ashley Ford’s “Five Things” posts. I’ve decided to give it a try, too.

I’m hoping that doing this will:

help me stay off Facebook

force me to share my thoughts and interesting links but won’t involve me getting sucked into the Borg

help me start blogging again

give me a place to put my thoughts so that I can come back to them later

Note: I’m not on social media much these days and don’t plan to “push” these posts via social media. So: if you’re reading this, it’s either because you subscribe to my blog or some nice person shared the link for some reason.

My novel is about Linda Lee Thomas Porter, who will eventually marry Cole Porter in 1919, but right now, I’m writing about her before she meets him. She was married from 1901-1912 to a rich dude named Edward Thomas. I like to refer to him as “the Charlie Sheen of the Gilded Age.” Ned and Linda were friends with the 5th Earl of Carnarvon who will eventually discover King Tut’s tomb, but in 1910 he was just getting started as an Egyptologist. Carnarvon and Ned both loved horses (they bred and raced them), racing cars, and had really automobile bad accidents that almost cost them their lives.

I finished a chapter on Saturday night that I’ve been working on for a week or two. It’s set at Carnarvon’s country estate, Highclere Castle (which you know as Downton Abbey) in 1910. I’ll admit that when I realized that there was a connection between Linda and Carnarvon, I got really excited about the prospect of “visiting” Highclere in my imagination. Because of the popularity of Downton Abbey, there’s a great deal of information on the web about Highclere: blueprints, detailed descriptions of the furnishings and architecture and the grounds, historical background. And thanks to this book, I know what what happening at Highclere around the time of my fictional visit. For example: on September 10, 1910 (my birthday as a matter of fact) a famous aviation innovator named Geoffrey de Havilland successfully flew a bi-plane prototype, and so I made Linda’s visit coincide with that that event so she could bear witness.

I purposely did NOT start watching season 6 of Downton Abbey while I was writing this chapter; I was afraid I’d lose my nerve or that I’d see the “real” space on the screen and think “I haven’t described the place enough!” or “I got that wrong!” or even “I’ve included too much!” The trick is to balance the real and the imaginary, to keep yourself from over-researching, to use the real as a springboard. I’ve always enjoyed this quotation from Mario Vargas Lllosa, who was asked by the Paris Review to explain what he meant when he said he “wanted to lie in full knowledge of the truth.”

“In order to fabricate, I always have to start from a concrete reality. I don’t know whether that’s true for all novelists, but I always need the trampoline of reality. That’s why I do research and visit the places where the action takes place, not that I aim simply to reproduce reality. I know that’s impossible. Even if I wanted to, the result wouldn’t be any good, it would be something entirely different.”

I’ve written before about how writing fiction is like time travel to me, and that’s a lot about what this chapter was about, actually. On top of the hill where de Havilland’s plane began its journey is the spot where Carnarvon wanted to be (and is) buried—Beacon Hill. He’s buried within the walls of a prehistoric hill fort, a place where people lived before England was England, even before Rome invaded. I don’t think it’s a stretch to imagine that Carnarvon was a time traveler too, someone who wanted to connect with the past, not through fiction writing but through archaeology and artifacts. It’s kind of meta, I know—a writer in 2016 imagining people walking around in 1910 who are imagining people walking around in 1000 B.C.

So: I watched a bunch of movies and TV shows set in distant past. The Eagle with Channing Tatum and Jamie Bell. Ironclad with James Purefoy. The Vikings TV series on the History Channel. Holy crap are these shows violent. I watched them in my home office. My writing regimen was this: I can’t write at a desk anymore because of my back, so I kick back in a chair and ottoman. When my fitness bracelet buzzed me that I’d been sitting for an hour, I got up and hopped on my elliptical and watched 15-20 minutes of people hacking each other up, then sat back down and wrote some more. Man, I’m glad I’m done with that chapter. I celebrated last night by watching Downton Abbey.

The post Five Things: 1/25/2016 appeared first on Cathy Day.

January 16, 2016

How I Taught Then, How I Teach Now

Last April, I was on an AWP panel moderated by Joseph Scapellato which included Matt Bell, Jennine Capo Crucet, Derek Palacio, and moi. The title was “How I Taught Then, How I Teach Now,” a subject that is near and dear to my heart.

Description:

Matt Bell discusses “the privilege of early access.

Matt Bell discusses “the privilege of early access.When experience forces us to challenge the assumptions that underpin our teaching philosophies, how do we sensibly revise our syllabi, course element by course element? In this panel, five teachers of writing share what they grew into knowing. They will describe how an active awareness of their changing assumptions changed their courses for the better. Practical before-and-after examples of course materials promise to make this panel useful for beginners and veterans alike.

Topics covered:

Matt talks about what he calls “the privilege of early access,” a way of framing workshop discussion.

Jeannine had some great suggestions for teaching students how to better analyze craft.

I talked about helping students to develop a writerly identity.

Derek describes a semester-long reading/craft project using Prezi.

Joseph read a great and hilarious essay called “Respect.”

Many thanks to the folks at AWP for turning our conversations into this podcast.

https://www.awpwriter.org/application/public/uploads/podcasts/mp3/AWPPodcastEp106.mp3

I actually ran out of time and didn’t get to talk about all the items on my list, so here it is.

How to Help Students Feel like “Real Writers”

These days, I’m less interested in teaching students “to write” and more interested in giving them the chance to feel like “real writers.”

That means helping them to:

1.) form an identity as a writer (or realize that no, they don’t want to “be” writers)

2.) take the next step in their career (toward a writer’s life or toward a writing-related career)

Story about when that moment happened for me:

I can tell you exactly the moments in my life in which I felt like a real writer. Most of them happened at the desk, from the inside out, but one happened when I got my first full-time teaching position at Minnesota State University Mankato.

My mentor Rick Robbins was helping me with my taxes, and he said, “You should file a Schedule C. Profit or Loss from a Business.”

“What business?” I said.

“Your writing,” he said. “You’re like a small business owner, really.”

That’s the day I realized that, in addition to being a college professor, I was the owner of a small business called Being the Writer Cathy Day.

Another example: It’s become common practice in creative writing classes to require students to submit work to a real literary magazine. These are the kinds of active learning assignments I like to use in order for my students to feel like “real writers.”

Here are some other ways:

Help them join a community writers and readers. Change what they see when they look at FB and Twitter.

If there’s a class you teach regularly, create a group on FB and require them to join. Or create a hashtag on Twitter and require that they use it.

They will meet each other and former students, even alumni.

These groups have become communities in which I can easily share advice and opportunities. They are places where we continue discussions we can’t finish in class.

Changing what they see on Facebook or Twitter helps them to see themselves differently.

Show them that writing isn’t “homework” and social media isn’t “private.”

Show them how to buy a domain name and/or start a blog. WordPress. Tumblr. Whatever. Because there’s something about becoming “Google-able” that’s important to identity creation in a networked age.

Use Google Docs in your class rather than Blackboard—because Blackboard is “school” and Google Docs is not.

Require them to create a professional email address such as cathyday@gmail.com instead of their edu address and instead of their first email address, which was probably something like ColtsFan287@yahoo.com or OneDirection4Ever@me.com.

Make them sign up for your Google Docs folder with that email address.

Have them use this new email address to sign up for their blog and create (if necessary) new Twitter accounts as well as LinkedIn, etc.

Show them how to transition to a more professional use of social media. Give them a few writers to follow who you think do it well.

Dedicate one of your classes (intro, intermediate, advanced) to helping students develop a regular writing regimen. In most classes, we put the most points at the end, in the portfolio. We assess the work that’s been revised and revised. Try this instead: require students to write 2 or 3 thousand words a week—of any quality. Put the most number of points in your course into the process, not the product.

Teach your students not just how to submit to literary magazines but to agents and editors as well. That’s something we almost never talk about in creative writing classes–not at the undergraduate level, and not even at the graduate level. So what if they aren’t ready for it? Someday they might be. And even if they don’t ever publish a book, they will be more informed readers when they understand the process a book goes through from artist to reader.

Teach your students how to pitch their novels. Every week when my students turn in their words, they have to preface them with a logline—one or two sentences that describe the story’s premise, like a film description in TV Guide: When BLANK happens to BLANK, s/he must BLANK or face BLANK. Or something like that. I look at their words, but I give feedback each week on those loglines.

Have your students write the jacket copy of their own novel or someone else’s. It’s very hard to synopsize a whole novel, yes, but it’s also like a scale model of the larger architecture of the novel. Summarizing can teach them a great deal about what’s going wrong and right in the novel as a whole.

Now that they have logline and jacket copy, they have what they need to write a letter to an agent. This is where I try to use a cross-class assignment.

Class A studies Agent Profiles online. They create a faux agent profile with photograph, bio, and the types of books they’re looking for.

Class B (the novel class) studies these profiles and submits their manuscript to the appropriate agents.

Class A receives vets their manuscripts and corresponds with Class B via rejection or acceptance letters.

My novel-writing class is the most unorthodox class I’ve ever taught. And the most popular. My evaluations are always positive, even though it’s the class in which I spend the LEAST time responding to their writing on the sentence level. – an example of how using the “privilege of early access,” Matt’s term, can lead to interesting learning outcomes.

The biggest difference between how I taught then and how I teach now is that the more I get out of the way and let my class be like a club, the happier my students are. And this astounds me, because I grew up learning in an entirely different way.

Final Note:

Some of you know that I’m on sabbatical this semester. I deactivated my FB and Twitter in November, but I reactivate them every 2-3 weeks just to check in, see my nieces and nephews, and deactivate again. But I wanted to come up for air today because I saw that this AWP podcast was up and wanted to share it with you!

I’m sorry that I haven’t been blogging a lot for the last few months. I started a blog post about why that is, but then I didn’t finish it.  Suffice it to say that I will be back soon, and I appreciate your patience. I’m on Instagram (I find that it doesn’t devour as much time because it’s not conversation oriented) and you can always reach me via email.

Suffice it to say that I will be back soon, and I appreciate your patience. I’m on Instagram (I find that it doesn’t devour as much time because it’s not conversation oriented) and you can always reach me via email.

The post How I Taught Then, How I Teach Now appeared first on Cathy Day.

September 13, 2015

A job pep talk for those with degrees in English

Yesterday, I sent out a series of tweets trying to encourage students in my department to go to the Job Fair. I think others might find the advice helpful as well.

[View the story “A Job Fair Pep Talk for #bsuenglish Majors and Grad Students” on Storify]

The post A job pep talk for those with degrees in English appeared first on Cathy Day.

September 9, 2015

On Turning 47

Two years ago, I wrote about turning 45.

Last year, I didn’t have much to say about turning 46.

But this year, I have thoughts about turning 47.

I have a lot of thoughts.

Today I decided to look through my calendar to refresh my memory from the past year. What I saw was a whole lot of doctor’s appointments.

Mine—I have a very bad back.

And my husband’s—he has been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

This has been a year of “coming to terms.”

I’m coming to terms with the fact that:

I sit at work all day long.

I answer emails and yack at people all day long.

I can no longer write sitting at a desk but rather reclined in a comfy chair or in bed.

I have trouble bending over to give the dog his peanut-butter pills.

If I sit down on the floor, I have trouble getting back up.

When I ride my bike, I almost can’t swing my leg up and over the seat (it’s a boy bike).

I probably need a step-through bike.

Eventually, I’m going to need a step-through bathtub or walk-in shower rather than the claw-foot tub we have now.

I can’t sit for more than 30 minutes or so before I’m very very uncomfortable.

I can’t sit for an hour or I’m in pain.

I have bursitis (bursitis!) in my left hip.

I’m going through menopause. Menopause!

I now wear tri-focals. Tri-focals!

I own an inversion table, a big rubber ball, an elliptical, and a yoga mat. They’re all in my home office, so that I can get up whenever I need to and stretch or hang or walk in place.

When I go see movies, I often sit forward in my seat, elbows on my knees, like I’m intensely interested in the film. But the truth is I’m just taking pressure off my spine.

I wake up about 10 times a night because of back pain.

My pain—even at its worst—is nothing compared to my husband’s RA pain.

His pain is harder for me than my own.

This has been a year of “losing my words.”

Searching for words to finish a sentence or explain a concept.

Not even difficult words.

For example:

My husband was going to the store.

“Be sure to buy some…” I paused. “Soap-a-ma-hooey.” I tried to turn it into a joke.

“What?” my husband asked.

“The stuff that makes our clothes clean.”

He laughed. “Laundry detergent?”

“Yes,” I said. Embarrassed.

After awhile, my husband said, “You know, this is happening a lot.”

It was happening in meetings and while teaching and other stressful situations.

It happened at home when I wasn’t stressed at all.

It happened when I was writing—my novel, sure, but also simple emails.

I told my doctor and she sent me for tests, and, sure enough, the tests confirmed that it was happening—but not why.

I’m a writer. I make my living writing words, saying words. All for an audience. Losing words is terrifying. Who am I if I don’t have the right words to express myself?

This is getting older.

In July, I bought a Jawbone UP because it tracks not just how many steps I take a day, but also my heart rate and my sleep.

My UP told me that I was getting practically no REM sleep or Deep Sleep, but mostly Light Sleep. I was also waking up a lot.

So: was I losing words because of my shitty sleep?

Or was it because I’m in menopause?

Or was it because I was taking four Neurontin and four Ultrams a day for my back pain?

I cut down on Neurontin. But I still word search. I still sleep kind of shitty. And I still don’t know exactly why.

I know. I know. This is getting older. This is life.

The year my marriage changed

In May, my husband went out of town to visit a friend in Nashville. He was gone for three days. I’m embarrassed to admit that before he left, I had to have him show me how to start the dishwasher. I’d never used it.

See, when we moved to Muncie (the most affordable college town in the U.S.) from Pittsburgh in 2010, we realized that we could live on my salary alone. I’d work—teaching and writing—and he’d take care of everything else.

And that’s pretty much how it’s been.

Until this year.

My husband started taking biologics (intravenously) for the RA pain, which is great, except these drugs also suppress his immune system.

Everything was going fine until April, when we flew to my annual conference in Minneapolis, and his fever spiked to 105. We went to the Hennepin County ER. He had a very bad infection. He got antibiotics and fluids. He went back to our hotel room and slept and slept and sweated through an entire king-size bed before the whole thing was over.

Since then, he’s been sick pretty frequently, despite the fact that he’s on antibiotics almost all the time.

He’s sick right now, as a matter of fact. Clostridium infection in his G.I. tract. I can’t seem to get his fever below 100, and I just got back from taking his stool samples (stool samples!) to LabCorp.

This has been the year of The Yard

This summer, when I wasn’t worrying about my health or my husband’s health, I was either writing my novel (slowly but surely) or working in my garden.

Why?

In June, the city of Muncie cut down two trees in front of our house. It’s good that they did this—they were dead and threatening to fall on our house—but it changed our shady, hosta-filled front yard into a sunny yard. We hired a grad student of mine to help, and whenever my husband or I was feeling up to it, we re-landscaped the yard.

You can follow the whole saga here, if you like.

I paid absolutely no attention to gardens growing up—too typically female—but I love them now—how they change just a little every single day.

In my front yard, I planted my mother-in-law’s prize day lilies and my great-grandmother’s Kansas Gayfeathers and my mom’s Surprise Lilies and my massage therapist’s peonies and pachysandra, and my neighbor’s Echinacea.

But what to do with all the hostas? The only option was to dig up the English ivy that carpeted our side yard.

Every few days, I’d go out there with a shovel and some pruners and some music to keep me going.

You have to dig about a foot down to get all the English ivy roots and rhizomes out of the ground. It was brutal, back-breaking work, but I loved it—the unthinking monotony of it—and somehow, my back never went out.

This was the year I got stronger.

Actually, this summer, my back got stronger. I can feel it in my thighs, my stomach, my hips when I walk. I feel like I did when I started practicing yoga 15 years ago, this sense of being more solid and balanced—like a weak ankle shored up by an Ace bandage.

The reason I worked so hard on the garden is that my husband and I have realized that we’re going to have to sell our big, beautiful house.

Why?

Eventually, going up and down the steps will be hard for him.

Even now, we struggle to take care of it.

When we bought the house in 2010, we’d just entered our 40’s, and my husband was so excited to be master of such a beautiful domain.

But within a year, he was complaining of pain quite frequently, and things in and around the house started to slide.

I realize now that it was the RA.

This was the year I lost “my wife.”

We also decided recently that my husband should go back to work full time. There are a lot of reasons for this.

The work is very interesting to him.

It takes his mind off the pain.

He likes being someone in this town other than Cathy Day’s husband.

The extra money will help us get the house ready to sell and help us figure out what comes next.

The first week that my husband started working full time, I sort of freaked out. It was me walking the dog and doing the laundry and the shopping and the cooking, etc.

The marriage I thought I’d have is changing into something that’s far harder than what I expected, and that scares me more than a little.

I know. I know. This is getting older. This is life.

My body and my mind are changing, and that’s scary, yes, and that, too, is life.

But you know what? I also feel myself getting stronger, more comfortable with the fact that I can only do so much to control all of this.

This was the year I blogged hardly at all.

If you’ve wondered why I haven’t blogged very much lately, this is why:

I haven’t been thinking much about my teaching—to be perfectly honest.

I’ve been so tired.

I’ve been coming to terms.

I couldn’t find the words.

But today (thank God! Praise the Lord! Holy shit!) I did.

The post On Turning 47 appeared first on Cathy Day.

June 20, 2015

A Lesson about Sentimentality

Tonight, I was going through a bunch of files and found one marked “Sentimentality.” It’s a craft lesson I once used in beginning creative writing classes to talk about cliché, abstract vs. concrete language, and unearned, Hallmark-y emotion.

It’s a one-page sheet. I’d pass this out and read it aloud.

Family

Oh, what a wonderful thing God has created. There can be no other thing in the world that God created that stands for anything more beautiful than the family. Everything else in life–money, friends, houses, cars, school, sports, jobs–can come and go, but the family is always there. God didn’t make it easy for the family, but he made it possible–with hard work and everyone working together, caring for each other and working as one. Yes, God made man, then woman, then said, Be a family. This will be my most beautiful creation.

This family means more to me than life itself.

Then I’d ask the students to respond. How did these words make you feel?

Some claimed that they were very moving.

Okay. Show me where you find it moving.

That last line. “This family means more to me than life itself.”

Who is saying that?

We don’t know.

Who is “this family” in the last line?

We don’t know.

When the speaker says, “God didn’t make it easy for the family,” did you picture a particular kind of trial?

Yes!

What?

A chorus of answers: divorce, moving across country, death, racial discrimination, class bias, illness, money troubles, alcoholism.

Did you maybe picture your own family or a family you know when I read those words?

Yes!

Write down a scene you pictured. As many details as you can. All five senses.

Furious scribbling.

Read aloud some of the concrete details you’ve written down.

I’d praise at least one particular, concrete detail from each student.

The smell of chlorine in an empty family pool.

A divorced father picking up his kids in a red truck, Led Zeppelin on the radio.

A boy knocking on doors, asking to mow his neighbors’ grass to make enough money so that his single mom could go buy something to make for dinner.

Trying to fall asleep on an empty stomach.

And so on…

So, this piece I read to you, I said, is it good writing or bad writing?

See, they get it now. “It’s bad, they say. Really bad. It’s vague! It’s sappy!”

What if I told you that I found this poem one day at a restaurant where I waited tables, left behind with an empty coffee cup and a full ashtray, written on a piece of notebook paper?

Are you making this up?

No, I’m not. [I’d reach down into my bag and pull out the piece of notebook paper, heavily creased and soft, like a t-shirt.]

This gave them pause. “Do you remember who was sitting there?”

No, I’d just come onto my shift.

They’d start to make up stories about the context, who had been sitting there? The handwriting looked like a man’s, they decided. Why did he write “Family”? What events precipitated his sitting down to write this–and why had he left the work behind?

This would go on for awhile, and then I’d reveal that “Family” was actually the second page of what I’d found. The first page was a note.

High Points to Make

1. There will be no open discussion. I will do the talking and you do the listening. (15 minute limit)

2. Mom and Dad’s reasons for working so hard at work and home.

a. Ways kids can show their appreciation or maybe they don’t.

b. Ways not to show appreciation: speeding tickets, drinking! *LAW

c. Not showing some pride around the house, your bedrooms, etc. You must have pride in yourselves and where you live, wherever it is!

3. We have taken into consideration many things and it’s time to start fresh (anew).

You kids are old enough now that leaving notes shouldn’t have to be done anymore. You can see (if you just look) the things that need to be done. Decide who is going to do them and get them done.

This house cannot operate with Mom and Dad doing it all! We’re killing ourselves slow but sure.

Having fun is everyone’s goal, so everyone has to share in the work, too. Freely, and not have to be forced to do it.

This family has been through a lot together. Maybe not as much as others, a lot more than most, but I feel it’s made us a stronger, closer family, and that’s all I ever wanted out of life was to be a strong, close family. We can do it if everyone does their share.

(over)

And on the other side of the page was “Family.”

More discussion. So it’s a parent, writing out what they want to say at some kind of family meeting?

What can you tell me about this family?

They laughed. “Looks like the kids got a speeding ticket and maybe got caught drinking.” They laughed.

What else?

It’s really cute how he put that little asterisk next to LAW! Like he REALLY wanted to emphasize that.

What else?

What’s up with “It’s time to start fresh (anew).” Why put anew in parentheses?

What else?

The family has been through something, but we don’t know what. THEY know what, but we don’t know.

The letter is not to us.

True…

If this was a short story, how would you solve this problem? [Here we would talk about point of view and exposition, etc.]

And so on…

At the end of class, I told my students the truth. I told them my story.

My father wrote that letter in the summer of 1987. When he read “Family” to us, he’d put down his cigarette and wept at the kitchen table.

We’d only recently started living all together again, you see.

The year before, the railroad had transferred my dad from Peru, Indiana to Cincinnati, three hours south. My parents had decided to move to a small town on Ohio River called Aurora, Indiana.

But I’d begged my parents to let me stay in Peru and graduate; I only had a year of school left, and I was ranked first in my class at the time. They said yes, which, in retrospect, was very unfair to my sister, who was only a year behind me in school, and she didn’t want to move any more than I did.

I spent my senior year living with a family friend in Peru. The day after I graduated from high school, I moved to Aurora, and my reintroduction into the family unit wasn’t going well–as the note above reveals.

That summer, my dad was pulling double shifts at the railroad, trying to make sure he’d be able to pay my room and board at DePauw.

My mom was working at the local hospital full time and going to college to get her degree.

Instead of stepping up and helping to keep the house in order, I was hanging out with my sister and her friends, getting into trouble. Parties. Boys. Speeding tickets. Drinking! *LAW! I’d start smoking. I was 18 and angry and scared to death and lonely. As rebellious teens go, I was pretty tame, but I’d fucked up enough to instigate a family meeting and my dad’s tears.

After the meeting, my dad left those two handwritten pages on the table, and I picked them up and took them with me a few weeks later when I went to college. I’ve carried them around for 28 years.

Things I’m thankful for:

My dad didn’t hit his kids when they caused trouble. He called a family meeting and tried to write a poem to tell us how he felt.

My dad didn’t go to college, but he made sure that his wife and kids did.

He grew up working class, generations back. But his three kids are now part of the professional class. And he accomplished this working a job he really didn’t like.

That morning, my dad looked at me and said, “Cathy, you’re getting ready to go to college. Do you know how important that is? I decided to stick with the railroad, and your mom and I decided to leave Peru, so that I could make enough money to put you through school. Every day, I drive an hour into the city and work a job I hate so that someday, you won’t have to work a job you hate. I don’t care what you end up doing, just as long it means something to you and you look forward to going to work every day.”

In college and graduate school, I met plenty of friends whose parents were in perpetual shame spirals over their children’s career choices.

What did my dad say when I told him I wanted to be a writer?

He said, “Whatever you want to do, I’ll support you.”

And he has.

Me and my dad on the Duquesne Incline, Pittsburgh, PA 2005.

Me and my dad on the Duquesne Incline, Pittsburgh, PA 2005.This is the story I told my creative writing students, and I’m telling it to you now.

Because it’s Father’s Day.

Because my father deserves more than he will ever get out of this life.

Because I want you to know–specifically–what I mean when I say I have a great father.

P.S. A few years ago, I wrote a Father’s Day post for everyone who didn’t have a great father. But this year, I needed to do the opposite.

The post A Lesson about Sentimentality appeared first on Cathy Day.

June 15, 2015

You Are Here: Teaching Students about Middletown, Indiana

This semester, I told my students that once upon a time, Muncie, Indiana was a boom town.

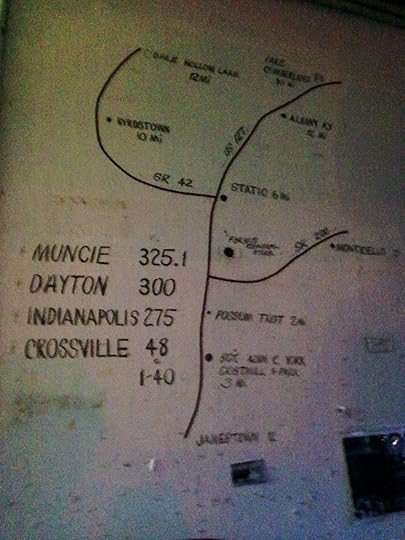

To prove it, I showed them this picture, taken by my Ball State colleague, Lee Florea. He hails from a small town in Kentucky, and this map is still painted on the wall of the local general store.

If this picture had a title, it would be, “Here’s Where the Jobs are How to Find Them.”

Once upon a time, a “river of immigrants” from Appalachia thought of Muncie as the Promised Land. The jobs they came for are all gone now, and Muncie is in the process of re-inventing itself. (Please, for the love of god, let’s hope it does, because I bought a house here, folks.)

My students are in college. They come to school from Indianapolis or Fort Wayne or Terre Haute and drive to their dorm, maybe to Wal-mart, maybe to Chili’s. Campus is their “home,” not Muncie itself.

How do you make a new place your home–even if just for a little while? That is a question I’ve been trying to answer for a long time.

For me, the answer has always been: learn the history. Immerse yourself in it. Travel through time.

I wanted to share that experience with my students.

Another New Class

So, during Spring 2014, I taught a new course: ENG 444, the senior seminar in my department. I called it “Research and Fiction.”

Actually, I’ve wanted to teach this course since I arrived at Ball State in 2010. It’s the capstone course in English and comprised of students from all concentrations (Creative Writing, Literature, English Studies, Rhetoric and Writing, and English Education). Their capstone project in our department must be a “major, student-driven research project.”

Actually, I’ve wanted to teach this course since I arrived at Ball State in 2010. It’s the capstone course in English and comprised of students from all concentrations (Creative Writing, Literature, English Studies, Rhetoric and Writing, and English Education). Their capstone project in our department must be a “major, student-driven research project.”

Did you know that The Circus in Winter was my undergraduate capstone project? It was a major, student-driven research project, too.

Not a research paper, but rather a researched story.

By teaching ENG 444, I wanted to demonstrate that “a researched story” and “a research paper” aren’t that different.

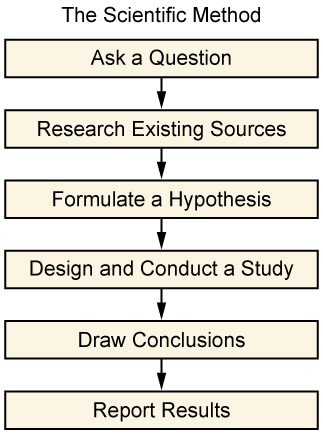

Actually, I wanted to demonstrate that the creative process and the scientific process aren’t that different.

I mean…look! –>

In my class, we discussed these essential questions:

What does “research” mean in the making of art? How do writers conduct research and incorporate it into their work?

When should you do research? At what part of the writing process? How do we avoid over-researching? How do we determine what material is relevant to our fiction and what’s not?

What forms can this research take? (reading books, interviewing experts, engaging in immersion journalism/ethnography, taking research trips to libraries or archives, and, of course, Googling).

What are the rewards and dangers of purposefully doing research as a fiction writer?

As someone who writes researched fiction, all of these questions are of great interest to me.

Here is the result: 16 linked stories set in historical Muncie, Indiana available for your reading and downloading pleasure on ISSUU.

And it’s also been added to the Ball State Middletown archives, which is very cool.

As you read the stories, you’ll see that:

The stories are linked by setting, character, and major events.

This anthology pays homage to the long history of Middletown Studies.

“Middletown” is a whole lot like Muncie, Indiana.

Every student in the class—not just the creative writing majors—contributed to the anthology.

Linked Stories

In The Triggering Town, the poet Richard Hugo advised his writing students to distance themselves from their real hometowns by creating a fictionalized place to call their own, a “triggering town.” This practice has a long-standing tradition in American literature:

Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River

Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg

Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County

Sinclair Lewis’ Gopher Prairie

These works inspired my own book The Circus in Winter about “Lima,” Indiana, a not-so-clever pseudonym for Peru, Indiana.

We began the semester by reading:

Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson

The Sweet Hereafter by Russell Banks

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

We talked a lot about the form, the difference that story order makes, and the ways in which the authors had purposefully linked their stories.

Using these books as models, my students began to create a fictional town. We called it Middletown, Indiana.

Middletown

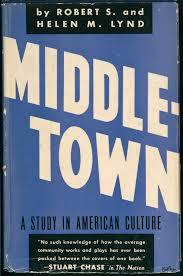

As you may know, Muncie is one of the most thoroughly studied cities in the country; in 1929 and again in 1935, sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd came to town in search of a “typical” American city, which they called “Middletown.”

Ever since, whenever researchers or journalists want to take the temperature of America, they come to Muncie—because it’s considered the most average small city in the country (which made my students chortle), a community that’s seen as the barometer of social trends in the United States.

We acquainted ourselves with the Middletown study by:

reading portions of the book, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture

watching portions of the Middletown documentaries (the landmark series from the 1980s)

touring the Middletown archives, thanks to Digital Archivist Brandon Pieckzo.

I also showed them this work of video art by my Ball State colleague (and neighbor) Maura Jasper, “Wish You Were Here.” She begins with a historical photograph and then slowly fades in a video of that site in the here and now.

Then they started writing. The only rule was that they had to set their story in a year in which they were not alive.

We also decided for sure that our Middletown would not be as white or as straight as the Lynd’s.

Structure

The Middletown study was famously divided into six “spheres.”

getting a living

making a home

training the young

using leisure

engaging in religious practices

engaging in community activities

Initially, I wanted to organize our anthology in the same way, but I decided it might be best to let students write whatever story interested them the most, in whatever time period interested them the most, in whatever sphere interested them the most.

What emerged were stories that were set from the 1920’s to the 1980’s. They dealt with race and class and gender, politics, war on the home front, unsolved mysteries, and friendship.

At first, there wasn’t much linking the stories except for the fact that they all took place in Middletown.

Then, I grouped the students into four groups of four.

The 1930’s group, which was about Muncie’s (and Indiana’s) troubled racial past.

The 1940’s group, which was about WWII.

The 1960’s group, which was about cultural changes.

The 1980’s group, which was about characters trying to leave Middletown.

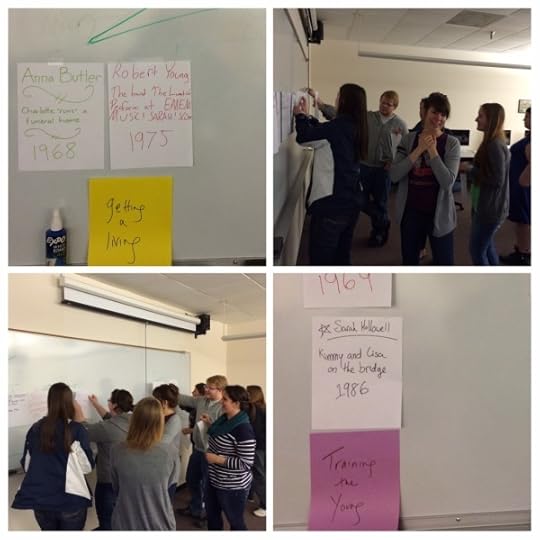

Storyboard Day in ENG 444

Storyboard Day in ENG 444They read each other’s stories and created “nodes of conjunction” between their stories. The main character in student A’s story became a secondary character in student B’s story. The setting of Student C’s story was incorporated into Student D’s story. And so on. You’ll recognize those linkages as you read.

Instead of an all-class workshop (which would have taken a full month of the course), they each gave a presentation: sharing a bit of their research and inspiration, followed by a short reading from their story.

Students voted on the title, the epigraphs, the order.

We did a storyboard of the anthology, laying all of the stories out on the board. We discussed how to best begin and end the book, whether to use chronological order or thematic order.

Ultimately, we decided on a roughly chronological order, but we did pay homage to the six thematic spheres—albeit in an ironic way. (Check out the anthology and see!)

It’s worth mentioning that students were not graded on their short stories, but rather on the essay they wrote about the writing and research process that produced the story.

What They Learned

Emphasis mine.

I found that even one sentence, or the premise of a story, takes research. I knew that the majority of things “historical” would have to be looked up, but I didn’t realize that every single part of the story is dictated by the time period. I also learned how to do research for characters; through other books and personal experience. This process was very important because growing up in academia, we are told to always look for “valid, credible sources” such as academic journals. However, those sources would not have been as helpful as photos of clothing or the map of Ball State’s campus in 1968. This process has changed my opinions on what is research and what its overall purpose is in writing and life.

In a literary analysis paper, which is what I’m much more accustomed to writing, you shine a light on your research. In researched fiction, though, the research needs to be invisible. This has consistently been one of the hardest parts of doing this research and writing this story. I do all this research and I want to say, “Hey! Look! I did all this research!” But this is not a research paper. Remembering that everything I put into the story has to be there for a reason, has to contribute and move the story forward in some way, was the most important thing that I had to constantly keep in mind throughout this process.

The research process, as I conducted it this semester, became much more of an unstructured process of exploration than the strict, orderly thing that I’ve always thought research to be. This de-familiarization of the research process has been an encouraging experience, teaching me that doing research is nothing to be afraid of, and furthermore, that it can be fun. I am happy with this outcome, because research is something that we, as human beings, do every day and in every situation, every time we survey a room, every time we pull out a smart phone, every time we ask a question of another person. It would be a shame to fear these things, to fear knowledge.

At some point in my school career, I became a lazy researcher. For term papers in elementary school I would go to the library and pour through book after book, making careful notes all along the way. In high school, I became a Googler. If I couldn’t find the answer in a Google search, I tended to decide that I didn’t really want or need to know it. I unlearned some of this in college, but I was still first and foremost a Google addict. I knew there were other sources out there, but I didn’t understand their value – and I didn’t until I started looking at research from a creative writing perspective. If you wish to truly understand and represent something in your fiction, it is not enough to Google the answers. Research must combine common sources like Google and books with out of the box sources like taking field trips and finding old yearbooks and popular magazines.

Throughout my journey to the final product, my research took many forms. I conducted interviews, analyzed photographs, watched videos, read magazines, watched documentaries, went to a house where a murder took place, read news articles, and looked at maps. Did everything appear in my story? No, but each source was rewarding in its own way because research, no matter how insignificant it seems, is still significant.

The End

I’m so glad that my students learned these things. I’m incredibly proud of the work they put into these short stories. And I’m humbled that we are adding another research artifact to the Middletown Studies archives.

And so I give you You Are Here: Finding Yourself in Middletown.

P.S.

I’m sorry that I didn’t blog while I was teaching this class. I wanted to, but just figuring out how to teach it sort of overwhelmed me!

P.P.S.

To my students, I’m sorry that I had to figure out how to teach this class as I went along. I appreciated your patience.

The post You Are Here: Teaching Students about Middletown, Indiana appeared first on Cathy Day.

May 19, 2015

Publishing in Print and in Pixels

I published my first short story in 1995. Twenty years ago. How can this be?

In Print

I was a graduate student at the University of Alabama. I’d been sending out my stories for two years without much luck. Then, over Christmas Break 1994, I went with my mother, a hospice nurse, on a “death call” in suburb of Cincinnati. The experience stuck with me, and when I got back to Tuscaloosa, I tried my hand at writing a “short short story,” or what we might call now “flash fiction.” 742 words. I sent it to Quarterly West. and they accepted it immediately.

When I got the magazine in the mail, I marveled at it for awhile, and then I put it on my shelf. My poet friend Tim kept the journals in which he’d been published in a place of honor on his desk, like a trophy case, and so I did the same.

I also added a line to my very brief curriculum vitae.

“Hospice.” Quarterly West. 41 (Autumn/Winter 1995): 6-7.

A year later, I published a story in The Florida Review about a man raising his daughter alone. Another magazine on the shelf. Another line on the vita.

“Leon’s Daughter.” Florida Review 21:2 (1996): 88-98.

Slowly, I kept adding more journals to that shelf. More lines to the vita.

Out of Print

In twenty years, I’ve published 14 short stories, which seems so paltry compared to some writers I know and admire, who seem to publish 14 stories a year.

Five of those stories ended up in The Circus in Winter, and as long as that book is in print, those stories live on. Note: All of them were published initially in print-only magazines.

“The King and His Court.” River Styx Vol. 66 (2003): 85-104.

“The Last Member of the Boela Tribe.” Antioch Review 61.4 (Fall 2003): 598-619.

“Jennie Dixianna and the Spin of Death.” Shenandoah 52:1 (Spring 2002): 98-111.

“Wallace Porter Sees the Elephant.” Southern Review 37:1 (Winter 2001): 107-120.

“The Circus House.” Story (Winter 1999): 21-31.

I highlighted #4 because that is the story that an agent happened to read and like. That story was the 10th story I’d submitted to that magazine over a six-year period. If you have read The Circus in Winter, it’s because of that story, that agent, and my determination to be published in that magazine, come hell or high water.

Eight stories were published in print magazines, which means that unless you subscribe to those magazines, you’ve probably never read them.

“Mr. Jenny Perdido.” PANK Magazine. Vol. 9 (2013): pp. 34-39

“The Jersey Devil.” North American Review 295:4 (Fall 2010): 7-12.

“YOUR BOOK: A Novel in Stories.” Ninth Letter 6:2 (Winter 2010): 129-139.

“Boats.” The Distillery: Artistic Spirits of the South. 7:1 (Winter 2000): 45-48.

“Strike Stew.” Cream City Review 23.2 (Spring 1999): 70-73.

“The Girl with Big Hair.” Gettysburg Review 12:2 (Summer 1999): 251-261.

“Leon’s Daughter.” Florida Review 21:2 (1996): 88-98.

“Hospice.” Quarterly West. 41 (Autumn/Winter 1995): 6-7.

One story was published online. Most people assume they can read my work online. They’ll say, “Hey, send me some links so I can read your stuff.” This was the only link I could send.

“Genesis.” Freight Stories 3:3 (September 2008): online.

Until today.

Reprint

A few months ago, a former student of mine who is the fiction editor for Burrow Press Review (which I’ll admit I’d never heard of) asked me if I had any stories that might fit their “Rust Belt Reprint” series. He said they would be reprinting stories by Dan Chaon and Sherrie Flick, two writers I know and admire.

Okay. I sent him a story called “Boats.” Go ahead–read it. It’s pretty short.

“Boats.” (reprint) in Burrow Press Review. (May 19, 2015): online.

I wrote “Boats” in 1998 in Mankato, MN so that I’d have something to read at their monthly reading series. You had 10 minutes to read, and then you got yanked. So I learned to write stories you could read in 9 minutes and 55 seconds.

“Boats was published a few years later in a magazine published at a community college funded by Jack Daniels.

“Boats.” The Distillery: Artistic Spirits of the South. 7:1 (Winter 2000): 45-48.

A grad school friend of mine was teaching there at the time and asked me to send something. “Don’t you have a story that’s not about booze?” he said. “I mean, we’re called The Distillery?”

A grad school friend of mine was teaching there at the time and asked me to send something. “Don’t you have a story that’s not about booze?” he said. “I mean, we’re called The Distillery?”

Sorry, I said. That’s all I’ve got right now.

He took it. Hurray!

Another line on my vita. Another journal on that shelf.

I don’t know if a single soul read “Boats” in The Distillery except for me and the editorial staff. And my mom, of course.

Print vs. Pixels

In those days, I never wondered who was reading my work. You published something. That was “sharing.” You put it into the world. You put the magazine on the shelf. You updated your cv. You went to the bar. Maybe–if you were lucky– it got mentioned in Best American Short Stories or New Stories from the South.

You expected no response whatsoever. There were no analytics to check. No “likes” to count.

Honestly, I miss those days sometimes.

But it also felt like writing into a void. There was no such thing as “online community.” You had to find IRL community, people to read your work.

Anything more than a form rejection letter felt like a small achievement; someone had actually read your story! They signed their initials! They wrote “Send more”!

We called that “getting ink.”

When I try to explain this to my students now they look at me curiously. They don’t understand a writer’s life before Submittable and email and urls and sharing.

It all seems so dim and far away now, but it was only 15 or 20 years ago.

Only. Ha.

Why publish?

I’ve been thinking about this all day–about time and the internet and publishing–ever since “Boats” went live at Burrow Press Review and I shared it lickity split on social media.

Why did I spend so many years trying to publish in magazines with 1% acceptance rates?

What did I want back then? Why did I want to publish at all?

To find readers? Never entered my mind.

To find an agent? Never entered my mind until I actually heard from one.

To be published in magazines I respected? Yes.

To build my credentials so I could apply for and then keep my academic teaching position? Yes.

To feel the joy and vindication that came with an acceptance in the mail? Yes.

What kind of “body of work” did I want to leave behind? Please. I was in my twenties. A bit of a mess. That wasn’t the body I was working on.

I had a fire in my belly back then. I still do, but the flame doesn’t burn as hot.

I wanted to publish back then so that I could “be somebody.” These days, I want to publish so that I don’t embarrass myself.

The Story Behind the Story

“Boats” is set in Dearborn County, Indiana, where my family moved when we left Peru in 1986. “Laurel” is a composite of two Ohio River towns: Lawrenceburg (home of riverboat casinos and Seagrams) and Aurora (home of caskets).

“Boats” is set in Dearborn County, Indiana, where my family moved when we left Peru in 1986. “Laurel” is a composite of two Ohio River towns: Lawrenceburg (home of riverboat casinos and Seagrams) and Aurora (home of caskets).

The mansion I describe is Hillforest Mansion in Aurora.

The people in the story are not my people (which is maybe why there are no distinct characters), but my family has lived longer in Dearborn County than they lived in Miami County–which seems an incredible thing.

I certainly don’t think this story is going to change the world, but I’m proud of it. And I’m glad that maybe a few more people will get to read it.

Thanks for reading. And thanks to Burrow Press Review for giving the story another chance.

The post Publishing in Print and in Pixels appeared first on Cathy Day.

March 29, 2015

All Fired Up About (Week of March 22-28)

Sometimes I end up blogging on Twitter.

It happened on Tuesday night, when it seemed certain that my Governor would sign SB 101

[View the story “15 Things I Love about Indiana ” on Storify]

The post All Fired Up About (Week of March 22-28) appeared first on Cathy Day.