Cathy Day's Blog, page 14

December 12, 2011

What They Learned This Semester

It's that time of year when our students turn in their portfolios–along with the "reflective essay" in which they articulate what they learned this semester. I love reading them. This term, I asked my students to turn those essays into blog posts. NOT something written to me, but to you.

It's that time of year when our students turn in their portfolios–along with the "reflective essay" in which they articulate what they learned this semester. I love reading them. This term, I asked my students to turn those essays into blog posts. NOT something written to me, but to you.

As you know by now, my goal for the last year or so has been to help my students move from "story" to "book" by tweaking how I approach my courses. specifically, how I run (or don't run) the workshop. I taught three classes this term, two of which had a public course blog attached to them. One was an undergraduate advanced fiction writing class on "novels" and a graduate course on "linked stories." But really, they were BOTH classes on novel writing–one explicitly (the undergrad) and one implicitly (the grad).

Each class has a blog, which you can peruse.

The Undergrad/Novel/Explicit Approach class blog is #amnoveling.

The Graduate/Linked Stories/Implicit Approach class blog is #amlinking.

Here are some highlights from #amnoveling:

Here are some highlights from #amnoveling:

Researching and writing a historical novel.

Beating writer's block by "writing without thinking" so you can surprise yourself.

Writing not just a novel, but a series of novels.

The benefits of planning vs. the benefits of not planning.

Writing a "novel that's true," and how you try and try to "get it right."

Honestly, all their posts are really great–about artistic influences, adapting screenplays into novels, talking themselves into attempting a novel in the first place, and writing a queer novel because you just really, really need this book to exist and it doesn't yet.

Here are some highlights from #amlinking:

Here are some highlights from #amlinking:

How writing in In Design–not MS Word–is helping one student create "haiku fiction."

The pedagogical advantages of a "linked stories" workshop vs. a de facto "story" workshop.

Stories as legos–a great analogy.

How "storyboarding" helps you move from "story" to "book." (Here's my post on "reverse storyboarding," which is how we started the semester.)

A few posts (here, here, and here) on how I "tricked" them into embarking on novels by telling them they were writing linked stories.

I know it's a busy time of year, but these blogs aren't going anywhere. Come back to them and read what my students have to say. If you're considering making some changes to your own creative writing teaching pedagogy, I hope you'll start a course blog, too, so that we can all figure this out together.

Happy grading, everyone.

December 11, 2011

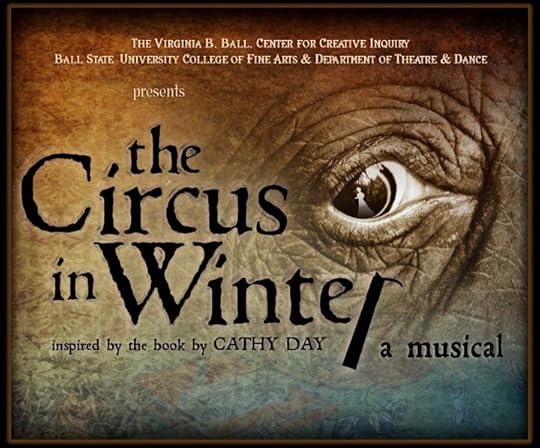

Another Chance to see Circus

The Circus in Winter will be going to the American College Theatre Festival in January!

The Circus in Winter will be going to the American College Theatre Festival in January!

Come see our Benefit Performance on January 2nd in University Theatre! If you missed it this fall, here is your chance to see it now! It's amazing.

The Circus in Winter

By the students of the Virginia B. Ball Center for Creative Inquiry

Inspired by the novel by Cathy Day

Directed by Beth Turcotte

Musical Direction by Ben Clark and Alex Kocoshis

Choreography by Erin Spahr

University Theatre

January 2 at 7:00pm

Tickets: $10-all proceeds will go toward the students traveling to the American College Theatre Festival

Based on the novel by Cathy Day and adapted for the stage by Beth Turcotte and students from the Virginia B. Ball Center for Creative Inquiry, The Circus in Winter is the story of the passion beneath the big top. Join Wallace Porter, a stable owner from Indiana, as he falls in love and searches for his life's work, a journey that culminates in the purchase of his own circus. Filled with fantastic characters, heart-rending moments of love an loss, and extraordinary new music, The Circus in Winter is a feast for the eyes, ears, and heart.

For more information, please contact the University Theatre Box Office at 765-285-8749 or boxoffice@bsu.edu.

Tickets will go on sale on December 12th! Box Office Hours are as follows: December 12-16 from 1-5pm, December 19-22 from 1pm-5pm, December 23 from 9am-Noon, December 28-29 from 1-5pm, December 30 from 9am-Noon and January 2 from 5-7pm.

Please come to Muncie and see this amazing production. You won't be sorry. I guarantee.

November 27, 2011

Storyboard Class

There are Two Kinds of Novelists

Outline people (aka "Plotters")

No Outline People (aka "Pantsers," because they write by the seat of their pants).

I am an Outline Person. I was born that way.

On Saturday, December 10 from 1-4 PM, I'll be teaching a class called "Storyboard Your Novel" for the Writers' Center of Indiana.

Here's the description:

Aspiring and working novelists can get a jump-start on their New Year's resolution to "write that novel." Author Cathy Day will offer practical advice on how to create a blueprint or "storyboard" for the book you want to write or are in the process of writing. Participants are encouraged to bring a package or two of index cards and/or lots of paper, Post-it notes, markers, etc.

I also suggest bringing a laptop if that's how you work best. The class will take place at Marian University, Clare Hall/#128. Here's a campus map. Here's the cost and how to sign up.

A few months ago, I taught a similar class at the Midwest Writers' Workshop and the attendees were incredibly motivated about mapping out their novels.

My storyboarding intensive at the Midwest Writers Workshop, July 2011

Really, storyboarding is a pre-writing stage that many of us skip because it doesn't feel like "real writing." But it is. Some novelists storyboard from the beginning. Some wait until they have a first draft. But almost all novelists do it.

If you're signed up for the class at WCI and you're reading this (or even if you're not), consider this doing this activity before Dec. 10: reverse storyboard a book you want to learn from.

How to Reverse Storyboard

Is there a book that's similar to the book you want to write? Meaning: it takes place over the same amount of time, uses a single first person narrator (Stephen Chbosky's The Perks of Being a Wallflower), uses multiple first person narrators (Tom Perotta's Election), uses multiple 3rd person narrators (Thomas Harris' Silence of the Lambs), switches back and forth between two different plot lines (Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain), uses an inner and outer frame (A.S. Byatt's Possession), uses multiple 3rd person narrators in non-chronological order (Dan Chaon's You Remind Me of Me), etc. Choose a book that does the one thing you're most nervous about, the thing you feel the least sure of in your own writing.

Don't pick a book because just because it's got a similar setting or the character is the same age as your main character. This is about understanding structure.

Read the book once for pleasure.

Read the book again using index cards or post-its (real ones or virtual ones) in order to thumbnail each scene in the book. Take note of WHO (pov character and who s/he is interacting with), WHAT (1-2 sentence scene summary), WHERE (setting), WHY & HOW (purpose the scene fulfills in the overall narrative). Make sure you number the cards in the corner, in case they get out of order.

If using different colored cards/post-it's helps you further visualize, great.

Determine what the major plot points are in the book. Narrow it down to 3-6 "big moments" in the book. Mark them.

Lay out the cards. Move them around. If there are 30 chapters in the book, lay out the cards in 30 descending stacks.

Now, what's Act 1, Act II, Act III?

Try rearranging the book in some other order—Dan Chaon's You Remind Me of Me arranged chronologically, or Silence of the Lambs with a prologue.

What can this book teach you about how to begin your novel, how to keep your reader interested in the middle, and how to work toward a satisfying end?

Storyboarding Really Works

In a recent interview, writer Rebecca Skloot says she knew "very early on that I wanted [The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks] to be a disjointed structure that told multiple stories at once and jumped around in time between different characters."

As soon as I realized I had to structure the book in a disjointed way, I went to a local bookseller, explained the story to her and said, Find me any novel you can find that takes place in multiple time periods, with multiple characters and voices, and jumps around a lot. So she did. Some of the most helpful books early on for me were Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café, by Fannie Flagg; Love Medicine, by Louise Erdrich; As I Lay Dying, by William Faulkner; Home at the End of the World and The Hours, by Michael Cunningham. I read a long list of similarly structured novels that all proved helpful in some way or another: The Grass Dancer, by Susan Power; How to Make an American Quilt, by Whitney Otto; Oral History, by Lee Smith.

Skloot knew the book was going to be a braid of three narratives (the story of Skloot and Deborah; the story of Henrietta and the cells; and the story of Henrietta's family), and so she "mapped it all out with index cards."

There it is. A bestseller. Three timelines. Three colors.

For the last year, my students have been completing reverse storyboards of published novels and novels in stories. I have found that it works like nothing else to help them move from "just reading" books passively—in order to be entertained or to interpret meaning—to reading books actively—in order to figure out how they work, how they will read, how to set up the effect they want the book to have. By breaking a novel down into its component parts, you contrive a way "to see" the narrative in one fell swoop. It's like taking an engine apart and putting it back together again.

Here are some other blog posts on this topic:

My grad students reverse storyboarding.

My undergrad students doing it.

I'm looking forward to a large class on December 10. Please come and learn how to write your big thing.

November 21, 2011

SOP: Do's and Don'ts

I've decided that my initial post was accurate, but vague, so I'm going to say some specific and potentially provocative things about that interesting little document called a Statement of Purpose. If you agree or disagree with me, great! Put it in the comments. I'd love to get some more do's and don'ts archived here.

I've decided that my initial post was accurate, but vague, so I'm going to say some specific and potentially provocative things about that interesting little document called a Statement of Purpose. If you agree or disagree with me, great! Put it in the comments. I'd love to get some more do's and don'ts archived here.

Don't talk about how, as a child, you loved to read and write. Everyone says that. For perhaps the first time in your life, you'll be with your kind of people! They all have the same story to tell about their journey as writers. But you don't have to tell how it started. We know. We've been there, too.

Do talk about who you read now, who influenced you. Everyone's journey starts in a very similar way, but they become very different and interesting later on. Don't focus on how your story started, Act I. Focus on Act II. Because what you're trying for is an Act III.

Don't say that your goal is to teach creative writing, eventually becoming a professor. I know that I might be the only writer you have ever known personally, but that doesn't mean that "being a writer" means "being a college professor." You don't aspire to it in the same way that say, you aspire to become a high school teacher. Your first priority is to self-identify as a writer. Aspiring to become a professor of creative writing is not a reasonable goal right now, the academic job market being what it is, and every time I read it in an SOP, I cringe inwardly and think that the applicant must be either naive or ill-informed. An MFA (even a PhD in Creative Writing) guarantees nothing in terms of employment, and you should understand that from the outset. It's not a pre-professional degree (like law school or med school) so disabuse yourself of this notion.

Do say that you want to be a writer, that you intend to pursue a literary life, and that the MFA is a step in that direction. If you become a writer, meaningful work of some kind will follow. An academic career is predicated on you becoming an expert in your field. Focus on that.

Don't try to talk abstractly about what creative writing is, what it's for, what it all means. You're not ready for that yet, and you're avoiding the topic of this essay, which is to state YOUR purpose, not the purpose of the discipline or the activity of writing.

Do talk about yourself. We want to know you, and you have to tell us concretely and specifically who you are. Where you worked. Where you went to school, who you studied with. What you read. What you've been doing since. How you have been making a literary life for yourself.

Don't talk about how much your writing life has sucked since you got out of college and how swell grad school will be. Grad school is not utopia. If you weren't writing outside the structure of "class," if you need to be "in school" in order to write, then I think that means you are not in the place you need to be in your adult life in order to make the most use of a graduate education. And especially do not say that everything about whether or not you become a writer is riding on my decision to admit you. That's emotional manipulation–and it's not true anyway.

Do say that that writing outside the MFA program hasn't been easy. Say that having spent some time "writing in the cold" (as my teacher Ted Solotaroff called it), you have learned to appreciate the opportunity, the time, the community, the mentoring, the rigorous training that graduate school will afford you.

Don't say that you are going to graduate school with either a.) a very very specific plan, or b.) no plan at all. I often tell my students that graduate school is the place where you go to polish a manuscript, not to generate one. But if your statement of purpose gives the impression that you will single-mindedly focus on your work-in-progress, then the question arises: why attend an MFA program and take a bunch of classes taught by veteran writer/teachers who might have something different to teach you? On the other hand, if your statement of purpose gives the impression that you have no work-in-progress at all, no sense of your subject matter or aesthetic, then the question arises: are you only pursuing a degree so someone will make you write? My preference when reading SOPs and Writing Samples is for students who DO have a sense of what kind of book they are coming to grad school to write, but I know that other faculty don't like this at all, wishing instead for a "blank slate" upon which they might inscribe themselves.

Do strike a balance between being dedicated to a project and being open to the possibilities. And know that there's absolutely no way to know how a given admissions committee will react to your particular plan. You can't know. Just like with the submission and editorial process, you put your work into the world and see where and with whom it sticks. If you're going to grad school to polish a novel and start another one, and the faculty aren't simpatico with that plan, then that's not the right place for you anyway.

Don't write a boilerplate statement of purpose and send to each school.

Do address what each particular school has to offer you. Mention the name of the literary magazine or a particular course you're interested in taking. Mention the name of a faculty member you're interested in studying with–while bearing in mind that s/he might not be the one reading applications that year, but rather another writer in that genre who wonders, "Hey, what am I? Chopped liver?" If the city or region has a particular attraction for you, mention that.

Don't go on and on, not about anything, but especially about the writing sample. Trust me, we're reading the writing sample. You shouldn't explain it much. We're reading so much, so many pages, actually, that if I look down and see that your statement of purpose has some glorious white space on the page, I will be inclined to fall in love with you a little.

Despite my previous advice–to imagine the SOP as you talking to me–don't forget that what you're really doing here is talking to strangers. Maybe you have a great anecdote about what a strange child you were, and this relates to how and why you became a writer. Dan Chaon talks about being a strange kid in an interview that appears in The Fitting Ends, how moments such as these were part of his journey in becoming a writer. But when Dan tells this story, he's doing so in an entirely different context than that of your Statement of Purpose. He's telling these stories as an adult, as a respected and well-published writer, as a college professor. If you told the same story in your SOP–about getting purposely getting lost in a department store and refusing to appear even when your mother called hysterically for you–I might be inclined to wonder about your mental stability.

Yes, writers are strange creatures, but try not to come off as crazy. Stay classy. Do remember that the people reading this SOP don't know you, and they especially don't want to invite unnecessary drama into their lives.

Do try to keep it under a page. Do make it easy on the eyes.

Don't write any sentences like this: "I am applying to your program in order to avail myself of the variety of opportunities you will provide in terms of my achieving my ultimate goal of being a published writer in the 21st century, whatever that means now or will mean in the probable future."

I'm not going to rewrite that sentence for you. I think you can figure it out for yourself. And if you can't–well then, young grasshopper, God help you.

[Here is an earlier post on requesting Letters of Recommendation.].

November 19, 2011

MFA FAQ: the SOP

Give them something good to read.

I often make these remarks to MFA program applicants: You'll never write a good Statement of Purpose (SOP) until you realize that everything I say today is wrong. It may be right for me, but it is wrong for you. Every moment, I am, without wanting or trying to, telling you to write the SOP I would write. But I hope you learn to write an SOP like you. In a sense, I hope I don't teach you how to write an SOP but how to teach yourself how to write an SOP. At all times keep your crap detector on. If I say something that helps, good. If what I say is of no help, let it go. Don't start arguments. They are futile and take us away from our purpose, which is to get you into graduate school. As Yeats noted, your important arguments are with yourself. If you don't agree with me, don't listen. Think about something else.

When you start to write an SOP, you carry to the page one of two attitudes, though you may not be aware of it. One is that the SOP should not sound anything at all like you. The other, that the SOP should sound like you. If you believe the first, you are making your job very difficult, and you are not only limiting the writing of SOPs to something done only by the very witty and clever, such as Auden, you are weakening the justification for creative writing programs. So you can take that attitude if you want, but you are jeopardizing my livelihood as well as your chances of writing a good SOP.

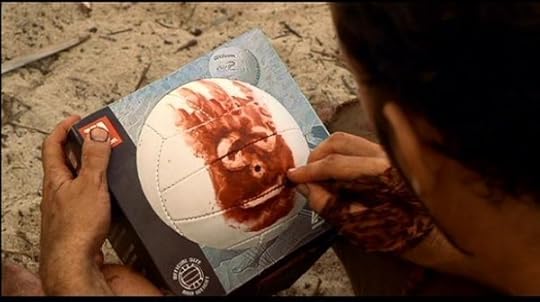

First, please read the previous post on this blog about finding your voice by talking to volleyballs or other imaginary people.

Then, tell me why you want to pursue an MFA in creative writing. We are sitting in my office on a Friday afternoon. Bells are chiming in the distance. When I smile and ask, "Why do you want to do this?" you answer from the heart. You're not trying to impress me with elevated diction or academic jargon. I know you struggle mightily with self-doubt. You keep asking me, Am I really a writer? and now you want to ask other people that question, and you are absolutely fucking terrified at what their answer will be. Forget them. Talk to me. I'm sitting right here with an encouraging smile on my face.

Okay. Now that you've got all that down. Pretend that I've invited some of my creative writing professor friends to join us. Revise what you just said, remembering that it's just not me in the room anymore.

Give us something good to read. I know you know how to do that.

And follow the directions below.

Some advice from Vince Gotera at the University of Northern Iowa:

Here's an organization I would recommend: (1) passionate hook; (2) segué to your background in the field; (3) specific classes by title and professors you have had (especially if well-known in the field); (4) related extracurricular activities (especially if they hint at some personal quality you want to convey); (5) any publications or other professional accomplishments in the field (perhaps conference presentations or public readings); (6) explanations about problems in your background (if needed); and (7) why you have chosen this grad school (name one or two professors and what you know of their specific areas or some feature of the program which specifically attracts you).

Some advice from Writing Program directors on the Creative Writing MFA Blog:

Erica Meitner: "I'm also a huge fan of the personal statement. It lets me know that the applicant can form full and compelling sentences (not always obvious from a poetry sample) and gives me information about a candidate's life experiences (which often gives me an inkling about whether or not they'll make a good instructor too, as all our accepted students are guaranteed TA positions). Alternately, I have colleagues who only look at the writing sample."

Mary Biddinger: "The document that most frequently takes the wind out of my sails is the statement of purpose. I would discourage applicants from making grandiose claims about what they'll do with the degree (a cushy 1:1 teaching load–all creative writing–immediately upon receiving the diploma, etc), and from spending time deliberating about the exact moment they decided to become writers, unless it's somehow intrinsic to the work. Knowing that you wanted to be a writer the minute you emerged from the womb is much less relevant than getting a sense of your current interests as a writer, and as a reader. I would encourage statement of purpose writers to "be themselves" as much as possible, while maintaining a sense of audience, of course. The best statements work in tandem with the writing samples, leaving readers with a lasting overall impression."

Me: Look, I know this hard and frustrating. I write SOPs all the time. They're applications for promotion and tenure, internal and external grant proposals, performance reports, etc. They go by many names, depending on the school, but for now, I'll just call them Academic Documents. It took me a long time to figure out how to write these things. I'd write an impersonal promotion application in the tone of a personal letter, as if there was an invisible title on the first page: "Things I Did This Year and Why They are Awesome." I'd write a formal letter addressed to a committee of literary scholars handing out research grants as if I was writing an email to my agent, the subject line being "Argh. My Next Book. WTF." I applied for academic positions as if I was blurbing myself.

Let's just say that I have made many mistakes along the way, but over time, I've also learned important lessons in how to apply for things. I've learned that I must imagine to whom I am writing, and then I must convince/seduce them.

And if you are sitting there resenting the fact that you have to write an SOP at all, then I say: Maybe you shouldn't go to graduate school, cuz wow, as a writer, you'll be stating your damn purpose in one way or another for the rest of your life.

You may have noticed that I didn't tell you how to write one of these things. I'm sorry. There is no answer to your question of "How do I write an SOP?" other than give 'em something good to read. Do that, and you'll be fine.

November 15, 2011

Talk to the Volleyball or "Know Your Audience" (Real or Imagined)

Blogging has taught me that some of my best writing–my clearest, most readable narrative voice–emerges when I imagine that I'm writing (or talking) to a specific group of people.

You may have noticed that I often interview myself here at "The Big Thing."

Really? I never noticed that, Cathy.

Well, I do. I learned this trick writing Comeback Season; whenever I got stuck, I'd bring out my handy-dandy sideline reporter Suzy Hightop. She asked me pointed questions, and I was forced to answer them. Eventually, Suzy became not just a device, but a real person to me. She became my Wilson, the volleyball/friend in Castaway with Tom Hanks.

Since I started blogging, I've learned that when a post is swirling around and going nowhere, I should make up fake interview questions posed by the ideal reader of that particular post.

Like who?

Sometimes, it's my students asking for a Letter of Recommendation or how to approach an assignment. Sometimes, it's all the people I know who loved loved loved Midnight in Paris.

As soon as I know who I'm talking to, boom, the words come and the structure of the piece aligns itself.

Sometimes I figure this out by accident. Over time, I've learned to pay attention when a letter or email or memo or Facebook comment starts taking on a life of its own.

For example: my story "YOUR BOOK: A Novel in Stories" which came out in Ninth Letter a few years ago got its start as a Facebook message to writer Kyle Minor, who I have never met personally but correspond with online rather frequently. About 1000 words in, I realized I wasn't writing a message anymore, I was writing a story, and so I cut and pasted the text from the little Facebook module into Microsoft Word, and boom, three days later, I had a draft of the story. (After the issue came out, I sent Kyle the story and said, "Thank you!")

Another example: a friend of mine wrote all the essays in his memoir as unsent letters to the kindest, smartest, most understanding person he knew: his MFA thesis adviser. My friend was in a dark place, and he wrote himself out of it by thinking, "I need to explain this to Kelly." My friend says that if you wrote "Dear Kelly" at the top of each essay in his book, you'd be reading almost exactly what he wrote during those long, lonely nights of anguish and doubt.

Another example: the piece that was published by The Millions about novels vs. short stories in creative writing programs–THE STORY PROBLEM! 10 THOUGHTS ON ACADEMIA'S NOVEL CRISIS!–started out as an email to my graduate fiction workshop, then it became a lecture to be read aloud to them, and then it became a very straightforward pedagogy essay to be submitted to the AWP Chronicle, and then it became more humorous and provocative, something I imagined I was saying to all my creative writing teacher friends on Facebook.

What brought up this subject, Cathy?

Well, I haven't posted here in a while. I've started at least a dozen posts, but couldn't figure out how to finish them. But then last night, I realized I hadn't written my 750 words for the day. I had some things on my mind about novel writing, advice for my novel writing class. I should write the class a letter, I thought. So I opened up 750words.com, typed, "Things I Want to Tell You," and "Dear Class," and boom, I wrote the whole thing in 30 minutes. And I really like it, so here it is, if you want to read it.

Now remember: it's not like I invented this strategy.

A few years ago, I went to a lecture by Junot Diaz in which he explained that some of his first stories were actually long, detailed letters he wrote to his brother, who was in the hospital with leukemia.

A part of the way I stayed connected to my brother was writing these enormous, ridiculous letters about what was going on about our lives, about the neighborhood, and in some ways my complete love of reading had prepared me for the moment that my brother's illness provided, which was an excuse to now participate in the form I loved so much. So that's how I started actually, writing letters to someone in a hospital.

In a recent article, Diaz talks about finding the voice of your narrator. "In my experience it won't kill you if you first figure out the character's relationship with the telling, with the story, before you even think about what kind of words, what kind of languages, what kind of attitude these folks will be slinging."

Another example: I attended a craft talk given by Russell Banks, who said that this is how he finds the voice of his narrators: by imagining a context for the talking, even if that context is never alluded to in the fiction itself. For The Sweet Hereafter, he imagined that each of the narrators was being interviewed by a kindly-but-shrewd lawyer; each has something different at stake in telling their side of the story. For Rule of the Bone, Banks asked himself, when does the hardened Chappie (aka "Bone") ever speak from his heart? The answer: at night, lying in bed, talking to an imaginary brother in the next bed. And that's he found his narrator's voice: by imagining just that situation and listening to his character talk.

There are times, of course, when you don't want to speak from the heart, when the situation calls for the impersonal, not the personal. For example: when you are applying to graduate school or for an academic position, or when you're applying for a grant or fellowship and you're competing in a pool of scholars, not creative writers. You gotta know who you're talking to, respect the way they like to be addressed, and speak their language.

This, of course, is when things get dicey. When we have to "code switch" from one vernacular to another. I'll hold off saying more until next time, when the subject will be MFA FAQ: the SOP (Statement of Purpose).

October 23, 2011

The Circus in Links

The eight-show run of The Circus in Winter: the Musical is at an end, but here are some links to news coverage, photos, videos, even a TV commercial about this amazing project.

The eight-show run of The Circus in Winter: the Musical is at an end, but here are some links to news coverage, photos, videos, even a TV commercial about this amazing project.

How did this adaptation happen?

Here's the backstory. And some more.

First, you have to understand Ball State's Immersive Learning Initiative. Yes, I know "immersive" isn't really a word, but still, it's a very cool idea, and one of the reasons I am excited to teach at a college that believes in such ideas.

Second, you have to understand the role the Virginia Ball Center for Creative Inquiry played in making this possible: an opportunity for students to TAKE A SINGLE CLASS and a faculty mentor to TEACH A SINGLE CLASS that's devoted to creating something. How do such things happen? Resources, baby. Resources.

You also have to understand Beth Turcotte, who is a force of nature. She talks about "waiting for the stars to align" here.

Me and Beth Turcotte at one of the readings of Circus, summer 2010.

You have to understand that one of the stars in her constellation was Ben Clark. Learn more about the genius who wrote (and scored) all of the music. Here's the short television commercial and a longer video about the whole process. These videos were filmed in my hometown at the Circus Hall of Fame, which is located on the grounds of the former Hagenbeck-Wallace circus winter quarters, the setting of my book.

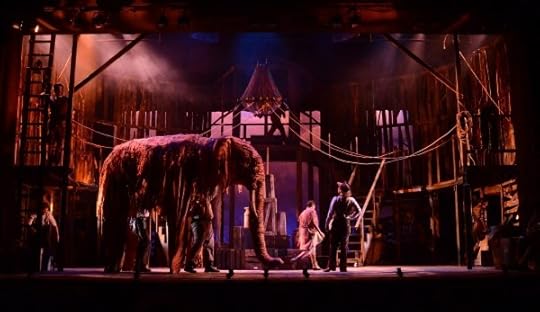

Here are two other stars in that constellation, the Wonder Twins. The set is an amazing work of art in and of itself, thanks to Christopher and Justin Swader. They used reclaimed wood from a real barn to create this round barn/circus tent.

What did the set look like? See above picture. And more pictures taken by the Ball State Daily News.

What did it sound like? Listen and see for yourself; they've uploaded a few videos to YouTube. Here's the opening number, "Amazing." Here's the story of the courtship of Wallace Porter and Irene Jones, "If I Could Know You." And the anthem "Circus Days."

There are so many stars that had to align. All of these, too, the group that originated this project during Spring 2010.

And these! The group that brought this project to the stage for its premiere.

As I gathered these links, I realized how difficult it is to tell the story about a theatrical production. Because it evolves over such a long period of time and involves so many different people, there are many, many links in the chain, so many stars that have to be in just the right place in the sky for something to work.

A novel comes into being from the imagination of a single individual; the final product shows the evidence of a few other hands–trusted readers, an editor–but in general, a novel belongs to the novelist. And then it goes out into the world, and sometimes the stars are with you and sometimes they aren't. Me, I've had it both ways.

It has been so enlightening and energizing to spend time with people who are artists in other mediums. They let me be a part of their creative process, and I can't thank them enough for that. I can't wait to see what happens next.

Speaking of what happens next: I've heard that DVDs of the performance will be sold via the BSU Box Office in order to offset costs as the musical is submitted to further festivals. I don't think it's ready yet, but here's the contact info.

Also, here's a bit of the coverage: Lou Harry, Arts & Entertainment Editor at Indiana Business Journal had this to say about the production. Writer Erik Deckers came to see the show and had this to say. Other links here.

October 18, 2011

MFA FAQ: The LOR

A series of posts about applying to graduate creative writing programs. This one's about the etiquette of asking for an LOR, or letter of recommendation.

Dear former student o' mine,

Thanks for your email/Facebook message asking for a LOR. I'm glad to hear that you want to pursue a graduate degree in creative writing.

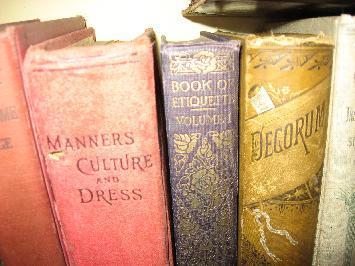

This is one of those moments in life—like graduation, marriage, the birth of a child, getting a job—in which you proceed through a gauntlet of people's attentions, and thus, you need to follow rules of etiquette—not just with me but with every single person you are about to encounter. Not to go all Emily Post on you, but mind your P's and Q's. If you aren't sure what those are, pay attention. I'm going to talk explicitly about implicit subjects related to the MFA Program Biz.

In an essay "Manners, Morals, and the Novel," Lionel Trilling said of this indefinable subject, "Somewhere below all the explicit statements that a people makes…there is a dim mental region of intention of which it is very difficult to become aware." He says that manners are "culture's hum and buzz of implication…the whole evanescent context in which its explicit statements are made…of half-uttered or unuttered or unutterable expressions of value…They are the things that for good or bad draw the people of a culture together and that separate them from the people of another culture."

Why am I saying all this? Because by asking me to help you get into graduate school, you are asking to join a culture called academia. When I applied to MFA programs 20 years ago, I was a first-generation college student from a working class family in a small, provincial town. Moving into academia was like moving to a foreign country. But I've lived in this country for a long time now. I've taught at four colleges, two of which had MFA programs in creative writing. I've read hundreds of admission files, sat in lots of rooms in which my colleagues and I discussed who to admit and why and who not to admit and why. I pretty much know what I'm talking about, but remember, I'm just one person and others might give you different advice—or they might not give you any advice at all because they think you should figure these things out for yourself.

Okay Cathy, what is the etiquette for asking for letters of recommendation?

Here's some advice. Here's some more. Note that neither of these pages is about asking for letters for a graduate program in creative writing. I've read plenty on this subject from those who ask for MFA LORs, but nothing from those who write them. Which is why I'm writing this, I suppose. I'm getting tired of saying this in my office and over email and Facebook every single year.

What do you need in order to write a recommendation for me?

I need:

The writing sample you'll submit with your application. Yes, I know you want to work on that up to the very last minute. But you have to send me what you've got.

A resume so I know what you've been doing since you graduated. If we are FB friends or if I follow you on Twitter, I have been passively following your journey all along.

A draft of your statement of purpose. Again, I know you want to work on this until the last minute, but I need to understand why you're applying so I can incorporate that into my letter.

Any and all paperwork—organized, filled out neatly, due dates clear. A list of all the schools where you'll be applying. Designate which schools use online recommendation systems and which ones use snail mail. If the school uses a snail mail system, you must send me all the paperwork, all forms filled out neatly, all the envelopes addressed and stamped. Here is my address, my rank, etc. You should endeavor to make this process as easy for me as possible. You should remember that I often write LOR's for 10+ people each year, and each of those people is applying to 5-10 schools. If you don't have your shit together, I will write your letter in an annoyed frame of mind, and you don't want that. Also, remember to always check the box that you don't want to see my letter. If you don't, they will not trust that my letter has been written confidentially.

When do you need all this?

No later than one month before the first letter is due. If you give me any less time than that, I will say not write it for you.

Don't you just use a boilerplate letter?

No, absolutely not. I spend at least 1-2 hours writing each of these letters. Remember: I've been on admission committees. I know my letters will be read by people in my profession. Unless they know me personally or by reputation, the only way my letter can truly help you is if I write it in such a way that I make a good case on your behalf. Of course, you have to make that case too—with your writing sample and statement of purpose. Seriously, these letters are not just some formality, some hoop I'm helping you jump through. When I vouch for you, I'm staking my reputation on you as a writer, scholar, and teacher (if it's a program where you'll be given the opportunity to teach). I'm saying to Schools A, B, and C that they won't be sorry if they accept you. I'm saying you're smart, talented, sane, mature. If you turn out not to be those things, then the next letter School A gets from me will matter just a little bit less.

Oh.

I know that y'all talk incessantly about these matters in various online forums. I found this comment on the Poets &Writers' message board:

The process of writing LORs, for professors at least, is a routine part of the job. Don't worry about the volume of LORs you are requesting…Your LOR writer has written dozens of these kinds of letters over the years and could probably compose one for you in minutes. If you're an especially talented student, he or she may even write something original. Regardless, the LOR writer will most likely use the same letter (swapping out names when necessary) for all of your schools.

This is so wrong it makes my teeth hurt.

But why do you need a month to write a letter?

Let me explain "my queue." Let me explain how you ask a really busy person for a favor—because as a writer, you will need to do this for the rest of your life.

There's an invisible pile of work on my desk, a queue of requests, and tending to this queue is both incredibly satisfying and really, really tiring. One reason I don't write book reviews is that I'm too busy writing all this other stuff instead; it's how I practice good literary citizenship. I write a lot of LORs for people I know personally. For residencies, colonies, fellowships. For academic positions. For scholarships. For grad programs in law, architecture, teaching, film, nursing, etc. I write letters/emails to agents and editors on behalf of writers I know who are looking to publish their book. I blurb books sometimes—which means I have to read them first. I write letters/emails to people I know who want feedback on their book manuscripts, their job applications, their teaching philosophy statement, their syllabi, their book proposal, etc. And, because I'm active on social media, I'm asked questions there CONSTANTLY. I derive a lot of joy from answering those questions when I can—because once upon a time, generous people answered all my questions, and this is how I pay it forward. But understand that my queue exists, and when you ask for a LOR, you're asking to be put into this queue.

I know this makes me sound like I'm some kind of fancy-ass writer. I'm not. In the scheme of things, I'm maybe low to moderate fancy. One thing I know: the fancier you get, the more people want to be in your queue, which means they will have developed a lot of rules about who gets into their queue and how they manage it. I shudder to think about the queues of [insert names of fancy-ass writers you know].

Why am I telling you this? Remember that the faculty writers you'll come into contact with during your MFA search have big queues, too.

Maybe I should just ask someone else to write my letter…

No. Someday, when you submit work to magazines, when you get an agent and an editor, you will find this same situation exists. Recognize that you're in a long line.

Don't not get in line because the line is long. That's dumb. Don't act like an asshole because the line is long. That's dumb. Don't not raise your hand to go to the bathroom because the line is long. That's dumb, too. At some point, you have to learn the fine art of being your own best advocate in this line without pissing people off. You might as well start now.

What will you say in my LOR?

Here's some advice I got once about how to write a LOR:

"Be specific and use examples. Speak to the student's performance in your courses, especially how they handled disappointments, criticism, pressure, and conflict."

So: If it's been a few years since you graduated, refresh my memory. Also: remember, it's really important how you perform in my classes, since that's what I'll be writing about.

"Know the student, know the opportunity they seek, and know why you've been asked to write the letter."

So: don't assume I know anything about the school where you're applying. Does it have a particular focus—on the environment, on hybrid genres? Is it an MA, MFA, or PhD program? Are you trying for a Teaching Assistantship? If there's anything unique about that program, tell me so I can speak to that.

"State who you are and the nature and length of your relationship with the student. Use comparative numbers or rankings when possible."

So: I have to say things like "Joe's writing ranks in the top 1% of all students I've ever had." Or "She was in the top 25% of students I taught this year."

"Be honest (but cautious)."

So: I'm not going to lie. Also, if I don't think I can write you a good letter, I will be decline to write you a letter. I might give you a reason (too busy, etc.) or I might just say "no." Don't argue with me or overthink this. You don't want someone to write you a letter reluctantly.

"Describe the person, not just the student. Use your particular viewpoint or lens into this student; don't repeat information available elsewhere on the application.

So: come see me during my office hours and let me get to know you. It's your job to teach me who you are, not the other way around.

"Know and meet the deadline."

So: remind me gently of my responsibilities. Remember, I might be sending 100 letters in any given year.

"Make the student work for the letter – give you enough time, and provide supplementary materials to help you write the letter."

Oh, student o' mine, I still have so much advice.

Like:

Please keep me posted about what happens—where you get in, where you don't, where you decide to go. A real physical thank you note is always appreciated.

Apply to 5-10 schools if you really want to get in somewhere.

Don't be snobby about geography. I once had a student who was torn between law school and the MFA. I talked to him about a bunch of good programs, including what I'll call Western State University, where a writer I knew had just been named director. A few weeks later, the student told me he'd decided on law school. When I asked why, he said, "Well, you encouraged me to apply to Western State, so you must not think I'm any good." Moral of the story: he really didn't want to get an MFA, but he wanted his not applying to be my fault, not his. Here's a good article about this topic.

If you want to teach someday, think about going for the PhD.

Don't use the P&W list for anything other than a place to start doing your own research.

Don't be fooled by snazzy websites or the prestige of the school generally. Those things have nothing to do with the quality of the MFA program.

Oh, I have so much more to say. Future topics: when to go, the statement of purpose, the PhD vs. MFA thing, the writing sample, the branding of MFA programs, and how to select the program that's right for you.

October 6, 2011

The Story of Jennie Dixianna

The first thing I did upon meeting Jennie Dixianna was kill her. I've regretted the decision ever since.

Over time, she became many things–acrobat, femme fatale, incest survivor, superwoman–but she was ephemeral and vague when she first popped into my head in Fall of 1991. Exactly twenty years ago. She made her very dramatic entrance in one of the very first stories I wrote for the big thing (I didn't dare even think of it as a "book" in those days) which I then called Circus People but which my wonderful editor Ann Patty wisely rechristened The Circus in Winter.

That story was "Winnesaw," the flood story, in which Jennie is introduced, flits around for awhile, and then [spoiler alert!] drowns while drunk, which is a really stupid way to kill a character.

So let me tell you how she was born.

I got the name "Jennie Dixianna" from this photograph of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus.

a photograph by Edward J. Kelty

If you look closely, you can see on the banner line that she's "America's Doll Lady," a euphemism for dwarf, someone who possesses some form of Restricted Growth. The real Jennie Dixianna, whoever she really was, is sitting next to the fat lady in this picture.

Another inspiration for Jennie was the real-life acrobat Lillian Lietzel. Her famous act, the One-Armed Plange, involved repeated turns on a hanging swivel and loop, revolutions which required her to dislocate her shoulder with each turn. This is where I got the idea for Jennie's act, "The Spin of Death."

Lillian Lietzel, circus celebrity, doing the One-Armed Plange

You need to know this: When I first created Jennie, I was living is Tuscaloosa, Alabama, attending graduate school in creative writing. The first night of my first-ever fiction workshop, one of my mentors, Allen Wier, read to us from the introduction of Carl Carmer's Stars Fell on Alabama, and the last sentence haunted me: "So I have chosen to write of Alabama not as a state which is part of a nation, but as a strange country in which I once lived and from which I have now returned."

Replace "Alabama" with "Indiana," and that's exactly how I felt about my homestate in 1991, the year I left (for what I thought was for good) to embark on my journey to become a writer.

A year or so after writing "Winnesaw," I tried to work my way backwards from the flood. Why would a man from small-town Indiana buy a circus? The answer to that question is contained in the story "Wallace Porter."

So: I needed to connect the dots. I'd already written "Winnesaw" so I knew that Wallace and Jennie were going to become lovers, and, now that Irene was dead, Wallace was free to hook up with Jennie. But how would such a pairing happen?

If you've read the story "Jennie Dixianna," I want you to imagine it sans all the backstory. That's how the first draft of that story read. I showed it to Thomas Rabbitt, who became my thesis director, and I've never forgotten what he said after reading it.

"Cathy, your stories are like Victorian dollhouses. You've got all the period details right, the set dressing, the costumes, but I never feel like I'm inside that house. I'm watching your characters go through the motions, deliver their lines, but I'm not emotionally invested in them. I don't feel like they are real people. They're like these little dolls that you're picking up and moving from room to room."

He pointed specifically at the Jennie Dixianna story to illustrate this point.

It was 1995. I'd been working on these stories for four years. I was so devastated after Tom said this that I briefly considered jumping off the third floor balcony of Manley Hall. But I knew he was right.

Some time after this conference, I was watching Inside the Actor's Studio with James Lipton. I don't remember who he was interviewing, but s/he said something about the difference between "delivering your lines" and "becoming your character." S/he said that in order to make the audience believe a character is "real," you can and should draw from some aspect of your personal experience. It's Method Acting 101, I suppose, but I found it enormously illuminating.

So I started figuring out what the hell was going on inside this Jennie Dixianna chick, what made her tick.

Eureka moment: Jennie thinks she wields a great deal of power over men. When in my life did I ever feel that way? Because, wow, at that point in my life, my twenties, I felt completely bewildered by the opposite sex. But then, I remembered, I thought I was pretty hot shit when I was seventeen (just ask my parents), so I channeled that and gave it to Jennie Dixianna.

Eureka moment: Then I started thinking, Who is this woman? How did she get that name, Dixianna? Why do some women sleep with all the wrong men? Why do they let such chaos into their lives? Why do they accept the slightest compliments as payment in full emotionally? When is promiscuity about power and when is it just really, really sad?

(These are very good questions for a young woman to ask herself in her twenties. Hoo boy.)

Eureka moment: Aha! Jennie is the victim of incest! Trust me, I get a lot of strangely-worded questions about this, all of them trying to find a way to ask me if this happened to me. The answer is no. Sure, I've got some Daddy Issues, but not that one. This aspect of Jennie is inspired by another Famous, Mysterious Dead Girl: Laura Palmer. I saw David Lynch's Fire Walk with Me in Paris during the summer of 1992, and was rocked to my core by the scene when Laura figures out who "Bob" really is.

Eureka moment: On p. 282 of Stars Fell in Alabama, in the chapter on "Mountain Superstitions," I found this:

"To stop a flow of blood, read a certain passage in the Bible. This verse is known to only a few people. When there is a bad case of bleeding the name and age of the unfortunate person is carried to the one having this power. He or she will retire to a room with the Bible. After reading the verse and chanting a few magic words, the conjurer will claim that the flow has stopped."

So that's how Jennie Dixianna's character came together over the course of about five or six years.

When I talk to readers of my book, they always tell me that Jennie is their favorite character, and so I wasn't surprised when I learned that she'd play a major role in the adaptation despite the fact that she only appears in three stories in the book. She's been played now by Maren Ritter, Jaclyn Hennell, Ella Raymond, and now, Erin Oechsel.

Photo by Kelly McMasters of the Ball State Daily News

Each of these women has played Jennie in a slightly different way, each one so beautiful and strong and sad, and I hope that they have learned something of themselves by playing her as much as I did by writing about her.

There's a scene at the end of the show where Wallace Porter is flanked by the two women he loved: Irene Jones Porter and Jennie Dixianna. One is dressed all in white, the other in gaudy reds and blues and greens. The good girl and the bad girl, so to speak, and I killed them both!

Why did I kill Jennie? That's the question that's been haunting me all week.

Maybe I couldn't imagine a future for Jennie because I couldn't imagine my own future at that point in my life. Twenty years after she first popped into my head, I sat there in the darkened theater looking at Jennie Dixianna, looking at my twenty-year old psyche dramatized on stage. I held my husband's hand, surrounded by friends and family, back home again in Indiana, thinking how strange and wonderful it is to be an artist, how worthwhile it is to keep trying to get something right so that your work can matter to someone else someday.

September 8, 2011

The Greatest Show on Earth

University Theatre of Ball State University

When:

September 29-30, October 1, 5-8 at 7:30 p.m., and October 2 at 2:30 p.m.

Who:

Adaptation by the students of the Virginia B. Ball Center for Creative Inquiry, Directed by Beth Turcotte, Musical direction by Ben Clark and Alex Kocoshis, Choreography by Erin Spahr

How to Order Tickets:

The box office is open from 12 to 5 PM Monday through Friday (765)285-8749 or boxoffice@bsu.edu $16 Gen. Adm., $12 Senior, $11 Student. Group rates are available.

How did this happen?

This explains it pretty well. Basically, the musical happened because 1.) Prof. Beth Turcotte at BSU proposed the project, jumped through the hoops, herded the cats, and drew the very best out of 2.) an incredibly talented group of young people with mad, mad skills, and 3.) it happened because of one devout fan of the book: Prof. Tony Edmonds. He's been teaching The Circus in Winter in his courses at Ball State since it was first published, and thus, when Beth's group got together to talk about a book to adapt, many had read it. It's extraordinary that a room full of people anywhere (other than in my hometown or perhaps in my parents' living room) would have my book in common.

How faithful is the musical to the book?

Quite faithful, but wisely (since my book is a collage and a good musical is a straight line), they only used the first five stories in the book. You'll meet Wallace Porter, Irene Porter, Jennie Dixianna, and Elephant Jack, Caesar the Elephant (yes! there's an elephant!) among others, as well as a few new characters not in the book.

What's the musical about?

Basically, it's an origin story; why does Wallace Porter buy a circus? "The Circus in Winter is the story of passion beneath the big top. Join Wallace Porter, a stable owner from Indiana, as he falls in love and searches for his life's work, a journey that culminates in the purchase of his own circus. Filled with fantastic characters, heart-wrenching moments of love and loss, and extraordinary new music. The Circus in Winter is a feast for the eyes, ears and heart."

Where do I go?

The University Theatre and Box Office is located on the Ball State campus behind Emens Auditorium, across the plaza south of Bracken Library.

Will you be there, Cathy?

Maybe. I can't attend every performance, but I will definitely be there opening night, Sept. 29, Sunday, Oct. 2, and on Thursday, Oct. 6.

Will there be a post-performance Talk Back so the audience can learn more about the adaptation and production?

Yes, it's on Thursday, Oct. 6 after the show. I'll be there, although my involvement in the production was quite minimal. The students and faculty who did the adaptation will be there (although some have graduated), along with members of the current cast and crew.

How does this feel?

I started writing The Circus in Winter exactly twenty years ago when I was a college student in Indiana, and it makes me happy that this adaptation was also done by college students in Indiana. Mostly, I'm just really grateful. These characters have been in my head for twenty years, and I can't wait to meet them. I'm pretty sure I'll cry a lot. It's a very overwhelming experience to have your inner truths sung back to you.

How can I learn more?

If you can't come to the show, follow the musical on Twitter @circusinwinter. They live tweet rehearsals.

May all your days be circus days!