Cathy Day's Blog, page 15

August 29, 2011

Twitter in a Creative Writing Class

Inspired by the way Adam Johnson shares innovative classes via Blogger, I decided to create a blog for two of my classes this semester. One is a graduate course on Linked Stories, and the other is an undergraduate course on Novel Writing. Long after the classes are over, the blogs will remain, archiving the experience of the course. I'm curating the Linked Stories blog, titled #amlinking, and my intern Lauren Burch is curating the Novel Writing blog, #amnoveling.

Why those titles? Well, if you use Twitter and you're a writer, I'm sure you recognize what I'm doing, so let me take a minute to explain hashtags to the rest of my readers. See picture below. Also, non-Tweeters should read this.

Twitter works a lot like Facebook Status Updates, except that that those updates can be categorized, and are therefore searchable. For example, a lot of writers use the hashtag "#amwriting." Let me use it in a sentence. "daycathy Just started using 750words again. Four days in a row! #amwriting." The # means I, which translates to #amwriting.

I quickly discovered the value of hashtags last year when my Novel Writing class participated in National Novel Writing Month. I started my first blog to share what I was learning in the course, and at first, I'd post the links to Facebook only. This is certainly effective, since most of my FB friends are creative writing teachers. But then I tried Twitter and started posting links to my blog using the hashtag #NaNoWriMo or #NaNo, and suddenly, I started hearing from lots of new people, strangers to me, who were doing NaNoWriMo on their own, looking for inspiration and guidance. Then I figured out how to search on Twitter and realized that, at any given time, I had direct access to thousands of people all engaged in the novel writing process.

Since then, I've found that Facebook is how I talk to people I already know, and Twitter is how I find (or am found) by potential new readers of my blogs and my books. I think of a hashtag as a party, a room full of people with the same interests, and you can either join a party by, say, live Tweeting the #VMAs or telling the world what you're reading on #FridayReads, or start a party by creating a hashtag and then see if anyone comes.

I got this idea from following my super-smart colleague Brian McNely on Twitter. Last semester, I noticed him Tweeting with a particular hashtag, and he seemed to be talking with his students. He told me that #4E1 "gave us a concise, easily identifiable hashtag that could act as a 'pivot' for social interaction among fellow travelers." That term, pivot, comes from Peter Morville, University of Michigan professor and expert in information architecture and findability.

Findability. It's what young writers want and need: to find a writing community and to be found. It's what brings them to the creative writing classroom. If you're the cynical sort, you might think I'm teaching my students publicity, marketing, branding, and I'll admit that yes, that's a by-product of what I'm doing. But mostly, what I'm trying to teach them is how to find the writing communities that will sustain them once they no longer have creative writing classes to attend.

If you're a fan of books like Winesburg, Ohio and A Visit from the Goon Squad, and definitely if you're engaged right now in writing linked stories, you can follow my graduate course by checking out the blog at iamlinking.blogger.com, or by following/using the hashtag #amlinking. (We also have a more private hashtag we'll use to talk about stuff that might not be interesting to you, like how to download that pdf off Blackboard, etc.)

If you're writing a novel or thinking about starting one, you can follow my undergraduate course by checking out our blog at iamnoveling.blogger.com, or by following/using the hashtag #amnoveling. (Again, we also have a more private hashtag we'll use to talk amongst ourselves.)

What I like about using hashtag searches to communicate with my students is that we don't have to be Facebook friends or follow each other on Twitter in order to communicate. Last week, I shared my social media policy here ("When Students Friend Me"), and the post seems to have struck a chord, given the number of reads it continues to get every day. Twitter is not a reciprocal relationship like Facebook, meaning, my students can follow me if they want to, but I don't have to follow them, which I like. And with hashtags, neither party needs to follow the other at all. We really only have one thing in common anyway–the course.

Another thing I like: when a student asks me a question using the Twitter hashtag, I'm making my answer transparent to all–in essence, teaching all of them (and you, if you want) at the same time instead of answering questions one-by-one, privately.

Some of my students are already microblogging as writers, connected as they are with the vibrant and incredibly supportive indie lit community. But I want to show all of them how this can be done, and I want to show them how to connect with their preferred online reading and writing community, whatever that might be.

August 22, 2011

When Students Friend Me

Before you send me that Friend Request...

[Teacher friends: Feel free to adapt this and use it on your own syllabi.]

MY SOCIAL MEDIA POLICY: This course will introduce you to the ways in which social media will become a part of your professional writing life. For example, we will use blogs and Twitter to share information with each other and connect to other writing communities. I have multiple email addresses and social media accounts that I use in order to communicate as my various selves: the writer and teacher me, who is mostly very public vs. the wife/friend/daughter/sister me who is more private.

When you "friend" me on Facebook or follow me on Twitter, you become a part of my professional network, not my private one, and I expect the same consideration from you. Consider your friend or follow request to be the moment you begin your transition from using social media for play and personal use to a more professional approach. You need to remember that your professors aren't your friends; they are mentors and supervisors. They will write letters of introduction and recommendation for you. Over and over, you will need them to vouch for you. They are "connections" in the best possible sense of that word. As you prepare to enter the workforce, and especially if you want to be a professional writer, you must learn to separate private communication from public. It is incredibly unwise to "friend" your professors and then complain about your classes, assignments, or professors, as if you are only talking to your close friends. It is also unwise to use social media to passively-aggressively complain about a professor's assignments or grades. In the real world, this sort of behavior might get you fired, or at the very least, might cost you a positive recommendation. On every recommendation form, I must assess your character, maturity, and discretion. Be appropriate at all times.

Before you send me that request, consider creating a profile or account that represents the Young Professional You, the Future You, not the High School You, Letting Your Hair Down You, I Feel Like Venting You.

August 13, 2011

Write the Book You Want to Read

Here's the course description for my course: Advanced Fiction: Novel Writing

Here's the course description for my course: Advanced Fiction: Novel Writing

According to a recent survey, 81 percent of Americans feel they have a book in them. I figure you're here today because you're one of those people. Good for you. Please understand, however, that you're not going to "write a novel" this semester, meaning you're not going to finish one, but you will start one. You will also learn what it will take to finish one and maybe even publish it.

I want you to start writing the book you want to read, not the book you think I want to read or you think your other teachers want to read, or anybody else for that matter, but rather the book that YOU want to read. I want you to start working on the book you've always wanted to write but you think you don't have time for, the one you think you're not ready for. This is an excellent opportunity to begin work on a manuscript to submit to MFA programs or to continue to work on after you graduate. At the very least, you will have gotten your "drawer novel" out of the way. For those of you who aren't necessarily planning on writing as a career or even a hobby, that's fine. You will leave the course a better and more appreciative novel reader—because you will have learned how hard it is to produce a novel, or what Henry James referred to as a "loose, baggy monster."

A novel is a big thing that's made up of lots of little things. You will write 3,333+ original words each week, which will result in a 50,000+ word draft. Remember, though, that 50,000 words doesn't even qualify as a novel; The Great Gatsby and Silas Marner are about 80,000 words long, and the typical novel is over 100,000. Of the words you produce, only 25-50 pages will be revised and polished and turned in as your final. Our focus this term is on quantity, not quality; process, not product. Yes, I just said that. This course will be very different from what you're accustomed to.

The form of your big thing can be a novel (the whole thing roughly sketched, or just a part of it more polished), a novella, or a novel in stories, but it cannot be a collection of unrelated stories. Preferably, your big thing should be fiction, but I will also allow nonfiction, since all long-form prose writers are concerned with similar questions about sustaining a longer narrative arc, about moving from stand-alone stories and essays to book manuscripts.

Note: There will be no all-group workshop. Yes, I just said that. You will not read everyone's work, and they will not all read yours. You will get feedback as the semester progresses, but not from every member of the class, only your small writing group. You will not always get feedback from me, as it would be humanly impossible (and counter productive) for me to read and respond to all the unvarnished words that will come out of your head this semester. Also, we will not be directly participating with National Novel Writing Month, although you are welcome and encouraged to do so on your own.

[More to come. I suppose I'd better talk about why I decided not to connect the course with NaNoWriMo this time.]

July 26, 2011

Add it Up

"Wait a minute honey, I'm gonna add it up…" — The Violent Femmes

Everyone gets their picture taken at the John Harvard statue, so I did, too.

I just spent a month thinking and writing and reading and researching. I lived like a monk, haunting the libraries, completely focused. There were no distractions—other than the ones I created for myself. Do you know what it's like, someone giving you money to think about something for a month? I'll tell you what it's like: it's pretty freaking awesome.

This is what I accomplished:

For my novel-in-progress:

I wrote two new chapters (25 pages) and completed a 10-page synopsis.

For my nonfiction project (for which I got the funding):

I read and/or reviewed 16 books and 15 articles or book chapters. I generated 100 pages of notes. Single spaced. I took 400 digital photographs of Linda Porter's scrapbook pages. There are 86 volumes of her scrapbooks at the Houghton, and I reviewed all but a few of them, along with scrapbooks belonging to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charles Eliot Norton, and Josephine Prescott Peabody, just to name a few. I also interviewed Daren Bascome, who owns his own branding business, Proverb.

How was this idyll made possible?

I received a Beatrice, Benjamin and Richard Bader Fellowship in the Visual Arts of the Theatre from the Houghton Library at Harvard University and an ASPiRE Research Grant from Ball State University. Thank you.

My colleagues at Ball State Tony Edmonds, Robert Habich, Mark Neely, Rai Peterson, Elizabeth Riddle, and Joe Trimmer looked over my proposal and/or showed me their own research proposals. Thank you.

My husband Eric Kroczek took care of everything during the month I spent hammering out these proposals, and he took care of everything during the time I spent at the Houghton Library. Thank you.

And because I couldn't work all the time, I took breaks with my former TCNJ colleague Michael Robertson, my old college chum Karen DeTemple, and my new writer friend, Lise Haines. It was also great to meet Elizabeth Searle, who was kind enough to let me sit with her at a production of Tonya & Nancy: The Rock Opera, one of the funniest and saddest and most wonderful things I've witnessed in quite some time.

A typical day included 6-9 hours in the Houghton Library reading room, a very pleasant place to spend the day, especially when it's 100 degrees outside. To save money, I'd bring something to nibble on outside rather than go out for lunch. Some days, I'd go to the Lamont or the Widener libraries to work and write, and a few days (not very many), I never left my little studio apartment. In the evenings, I found that I couldn't read. I think the human brain can only absorb so many words in a day. So, I watched a lot of BBC and Masterpiece Classic series on Netflix or YouTube. My favorites were North and South (based on the novel by Elizabeth Gaskell, and no, it doesn't have anything to do with the Civil War) and Daniel Deronda. Many thanks to the Facebook group British Period Drama for the daily suggestions.

It was a great month. And now I return to real life with a purse full of receipts for the other kind of accounting that I will no doubt have to do.

Accounting: Trying to Add it Up

I just spent a month thinking and writing and reading and researching. I lived like a monk, haunting the libraries, completely focused. There were no distractions—other than the ones I created for myself.

Do you know what it's like, someone giving you money to think about something for a month? I'll tell you: it's pretty freaking awesome.

This is what I accomplished:

For my novel-in-progress:

I wrote two new chapters (25 pages) and completed a 10-page synopsis.

For the related nonfiction project/s (for which I got the funding):

I read and/or reviewed 16 books and 15 articles or book chapters. I generated 100 pages of notes. I took 400 digital photographs of Linda Porter's scrapbook pages. There are 86 volumes of her scrapbooks at the Houghton, and I reviewed all but a few of them, along with scrapbooks belonging to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charles Eliot Norton, and Josephine Prescott Peabody, just to name a few. I also interviewed Daren Bascomb, who owns his own branding business, Proverb.

How was this idyll made possible?

I received a Beatrice, Benjamin and Richard Bader Fellowship in the Visual Arts of the Theatre from the Houghton Library at Harvard University and an ASPiRE Research Grant from Ball State University. Thank you.

My colleagues at Ball State Tony Edmonds, Robert Habich, Mark Neely, Rai Peterson, Elizabeth Riddle, and Joe Trimmer looked over my proposal and/or showed me their own research proposals. Thank you.

My husband Eric Kroczek took care of everything during the two-week period I spent hammering out these proposals, and he took care of everything during the time I spent at the Houghton Library. Thank you.

And because I couldn't work all the time, I took breaks with my former TCNJ colleague Michael Robertson, my old college chum Karen DeTemple, and my new writer friend, Lise Haines.

It was a great month. And now I return to real life, where I will have to turn in a form accounting for this trip in monetary terms.

July 20, 2011

Midnight in Paris & Fantasy Linda

A sincere thank you to everyone who wrote me to make sure I knew about Midnight in Paris. This is the conversation I imagined having with all of you about the movie.

A sincere thank you to everyone who wrote me to make sure I knew about Midnight in Paris. This is the conversation I imagined having with all of you about the movie.

Hey, you said, do you know that Cole Porter is a character in this new Woody Allen film?

Yes, I do know this.

Have you seen it?

Yes, I went to see it with my mom, with whom I also saw De-Lovely, as a matter of fact.

Well, what did you think?

Of De-Lovely?

No, Midnight in Paris?

I liked it. Who doesn't like [spoiler alert!] a time-travel fantasy/love story with a happy ending?

Are you being sarcastic?

Sorta. I can see why it's Woody Allen's highest-grossing film to date. But it's not really about traveling back in time. [You know that, right?] Gil/Woody doesn't return to the real past so much as he enters his own Golden Age, his idealized perception of that time and place and the people who inhabited it. Inez tells Gil, "You're in love with a fantasy," as they embrace on a bridge, surrounded by water lilies.

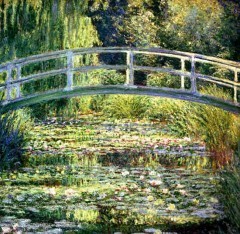

Even if you can't tell a Monet from a Manet from a Degas, I'll bet you recognize this scene in the movie. We've all been to Fantasy Giverny—thanks to hotel room decorators and Deck the Walls and college poster sales.

See, that's what makes Midnight in Paris so enjoyable, and why it's doing so well at the box office. The movie makes us feel smart, because we recognize Hemingway doing HEMINGWAY and Scott and Zelda doing SCOTT AND ZELDA and Cole Porter doing COLE PORTER.

The only people I know who don't like Midnight in Paris are people who actually know a lot about Paris in the 1920s. It's hard to be swept away by the romance of it all when you're invested in the reality.

Cathy, everyone likes this movie. What's your problem?

Look, I like it, too, but here's my problem. For as many times as Gil invokes their famous couple-dom ("Cole and Linda!" he keeps saying throughout the movie), you'd think Woody Allen might have hired an actress to actually play her. And he didn't. I know. I stayed and watched all the credits.

Well, it's not like Cole got a lot of screen time either.

True. It's his music that makes him seem so present in the film, when actually, he's only got a bit part, played by . On his first midnight trip to Paris, Gil sees Cole at the piano, and later, they drive in a large group to a bar

I guess we're supposed to imagine that Linda is one of the anonymous females in this car?

where their merry group is entertained by a African-American woman who might be Bricktop or Josephine Baker or an amalgam of them both.

Showoff. So you're saying that Linda should have had a bit part, too?

I'm saying that if you really traveled back to Paris in, say, 1925, Linda was the big deal, not Cole.

But he's Cole Porter!

He wasn't THAT Cole Porter yet. By virtue of her high-profile first marriage to Edward R. Thomas (a millionaire playboy) and her high-caliber friends, Linda was well known long before she met Cole Porter. She was the celebrity. In fact, you might say that by marrying him and making sure that the papers referred to her as "Mrs. Cole Porter," she was doing him the favor, not the other way around.

But he's Cole Porter!

As far as most people she knew were concerned, he was just this little musical fellow from Peru, Indiana.

But he went to Yale!

Maybe that makes him royalty in Indiana, but it doesn't get you very far with actual royals.

But I love his music! He was so talented!

I love his music too, but in 1925, his talent wasn't apparent yet. A few years earlier, his first Broadway effort, See America First, had flopped. The New York Herald review said "its plot is silly, its music unimpressive" and suggested "it would be delightful as a college play . . . with the audience consisting of fond relatives." The critic for The New York Tribune agreed, observing "Gotham is a big town and it may be that the sisters, aunts, and cousins of its Yale men will be sufficient to guarantee prosperity for See America First."

Ouch. But he must have done something good at that point?

Cole had enjoyed only one hit, a song called "Old Fashioned Garden," which, when it was released in 1919, struck a sentimental chord with soldiers returning from World War I. Listen to this song! It's seriously hokey. There's no hint of "Let's Misbehave" or "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love" or any of the kind of music that will come.

Okay, remind me: what is the big deal?

I'm writing a novel about Linda Lee Thomas Porter, a woman who—despite being featured in numerous biographies, despite being portrayed in two major motion pictures, despite her contributions to Cole's career—nobody recognizes by name unless I refer to her as "Cole Porter's wife." And just as I'm writing that novel to try to rescue her from this oblivion, a movie comes out in which she's constantly talked about, but only her more famous husband actually appears in it. So yeah, it's a big deal to me.

You mentioned the other movies. What about De-Lovely? Wasn't that movie, that Linda much more historically accurate?

Well, De-Lovely (2004) certainly did a better job of telling Linda's story than Night and Day (1946), which, among its many, many inaccuracies, never mentions that Cole was gay.

Well, they couldn't…you know…talk about…that.

Yes, I know. Film execs believed that Cole's story, particularly the focus on his crippling leg injuries, would resonate strongly with a country anxiously welcoming home soldiers from World War II. Watch the clip I linked to above. The filmmakers–on America's behalf–needed Fantasy Linda to run to Fantasy Cole with love and acceptance in her eyes. That's the story they needed to tell, and Real Linda and Real Cole were happy to go along with the charade. I mean—who doesn't want a freaking movie made about your life while you're still alive? Who doesn't want to be played by Cary Grant and Alexis Smith?

Or Kevin Kline and Ashley Judd?

Right. But Kline and Judd were playing Fantasy Cole and Fantasy Linda, too. While I certainly give this film credit for finally addressing Cole's homosexuality and at least attempting to capture the Porter's unique marriage, De-Lovely tries very, very hard to heteronorm Cole and Linda. Fantasy Cole has sex with Fantasy Linda, who miscarries their Fantasy Baby. (I've read all the Cole Porter biographies, and only one—the least reliable one—makes this claim.)

De-Lovely also makes it seem as if Cole and Linda were "couple friends" with Gerald and Sara Murphy, when the truth is the Murphys really didn't like Linda at all.

Famous picture of (l to r) Gerald Murphy, Ginny Carpenter, Cole Porter, and Sara Murphy. Venice, 1923. Linda nowhere in sight.

When Cole and Linda were together (which wasn't all that often), they were among their tribe of interesting single individuals. Even their friends who were married (or in committed same-sex relationships) socialized on their own. Cole and Linda just didn't do bourgeois couple things, but the filmmakers of De-Lovely needed them to, presumably so that this biopic might enjoy the same wide appeal as Ray and Walk the Line.

When I reviewed the contents of the Cole Porter Collection at Yale a few years ago, I read an interesting letter from the company that produced De-Lovely, a routine bit of correspondence, really, asking for photos of the real Cole and Linda to accompany publicity stills of Kline and Judd. "We want shots of Linda and Cole—without the entourage that seemed ever-present in their fascinating life." Ha. There aren't many of those. Over the last few years, I've reviewed thousands of pictures in different Cole Porter collections, and there are very, very few of just the two of them together.

There's definitely nothing like this:

Cole and Linda curled up on the couch. Ha!

Cathy, if a Daimler pulled up one night and offered you a ride to Linda's house at 13 rue Monsieur, would you go?

Of course.

Would you rather meet the real Linda Porter, or your Fantasy Linda?

Good question. I'm going to say, Fantasy Linda," Linda Porter doing LINDA PORTER, but I hope I've worked hard enough, researched enough, so that even my dream of her will be closer to the truth than what's come before.

May 20, 2011

Linda Died 57 Years Ago Today

Linda Lee Thomas Porter died on this day, May 20, 1954. She died in her apartment in the Waldorf Towers after a long battle with emphysema.

Linda Lee Thomas Porter died on this day, May 20, 1954. She died in her apartment in the Waldorf Towers after a long battle with emphysema.

Linda described her illness as "smothering spells." Imagine that: smothering to death over the course of a decade. She once said, "I suppose I shouldn't want to stop coughing as I have coughed for so many years, if I stopped, the shock might kill me."

Here's what helped her live a few years longer than she might have otherwise:

Her own personal oxygen tent.

Air conditioning.

Recuperative trips to Arizona ranches and Colorado luxury hotels, where the air was drier.

A summer mansion in the Berkshires, far away from hot, humid New York. She bought the mansion the year Cole started spending summers in Hollywood. Linda said she couldn't breathe in California, although it's not clear whether the problem was air quality or Cole's somewhat decadent pool parties.

And then, for the last two years of her life, Linda was virtually housebound. Or rather, Waldorf bound. Every morning, she'd rise, do her makeup, don a tea gown, and make her way to the sofa. Cole lived in a nearby apartment, and if he was in town, they'd lunch together, but they didn't see each other a lot otherwise.

She received many visitors. One of them, Lady Astor, noticed that two brand new Mainbocher evening gowns hung in Linda's closet, purchased in the hope that she'd recover enough to wear them someday. Lady Astor reportedly said, "Why don't you give me your Mainbocher's. You'll never wear them again."

This was two years before she died.

Towards the end, Linda coughed so hard she broke a rib. Her once-great beauty was completely gone. Her pain medicine and lack of oxygen made her mind vague. She slipped in and out of consciousness, struggling to breathe. In May 1954, Cole was in California working on the score for Silk Stockings, but a week before she died, the doctors said he needed to come to New York. It was time.

When she first saw Cole, Linda was lucid enough to say, "I want to die. I'm in so much pain." She asked Cole to bury her outside her mansion in Williamstown, Buxton Hill. He agreed. She held his hand and said, "If only I was important enough so that a flower or something would be named for me."

And sometime after that, she died.

The Linda Porter Rose ('Miguel Aldrufeu')

Cole did have a rose named in Linda's honor, but he didn't bury her in Willisamstown, as she asked. Instead, he buried her in my hometown, Peru, Indiana, in the Cole family plot at Mount Hope Cemetery, where many of my own family members are buried. I used to ride my bike through this graveyard. I thought the Cole family gravestones looked like tiny baby teeth.

The Cole Family plot, Mount Hope Cemetery, Peru, Indiana

A few months ago, I was in New York and went on a historical tour of the Waldorf-Astoria. Cole Porter is a main character in "The Waldorf Story," his name invoked over and over again, but when I asked the tour guide if she knew anything about Linda, she said, "Isn't it sad that she died so young."

I said, "She didn't die young. She was in her 70's."

The tour guide got defensive. "Well, I don't know about that."

At that moment, we were on the 41st floor, touring an empty apartment. I couldn't help but wonder if it had been Linda's. "So you know if this apartment was Cole's or Linda'? They had adjoining apartments on this floor."

At that moment, we were on the 41st floor, touring an empty apartment. I couldn't help but wonder if it had been Linda's. "So you know if this apartment was Cole's or Linda'? They had adjoining apartments on this floor."

The tour guide shook her head. "Cole Porter's apartment was on the 33rd floor. That I know!"

"Yes," I said, "that's the apartment he moved into after Linda died. The one decorated by Billy Baldwin. But they lived on the 41st floor for decades." I fought the urge to reach into my bag and pull out Cole Porter's biography.

The tour guide smiled tightly and walked away.

Yes, I was showing off, being a smarty pants. Also, I wanted an impossible thing: for the official historical tour of the Waldorf to tell Linda's story, too. I wanted everyone on that tour to know that the money that paid for Cole's apartment and grand lifestyle was just as much hers as his. I wanted them to know that Linda devoted her life and her fortune to making sure that he would become someone great, someone we'd always remember.

And so, when I was in Peru the other day visiting my grandparents, I stopped by Linda's grave. It's very strange to stand at the real grave of your fictional character. I didn't have a rose on me, only a Milky Way candy bar.

I stood there a moment. I looked at her gravestone.

All the other Cole gravestones indicate date of birth and death, but not Linda's. I guess that after making sure the stone read that SHE WAS THE WIFE OF COLE PORTER, there wasn't room to tell us when she was born (November 17, 1883).

I thought about all the women I've ever met—in life and in books—who married great men rather than pursuing greatness themselves. I thought of all the sisters and wives and mothers and devoted daughters—all the Lindas—behind every beautiful thing.

I felt silly, but I said it. Out loud. I told her I was trying my best. I told her she wasn't forgotten.

May 15, 2011

Aesthetic Diversity + Imitation = My Short Story Class

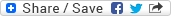

In honor of National Short Story Month, I thought I'd share this course with you, a short story survey that focuses on imitations. I always include this picture on my syllabus, a visual representation of my pedagogical approach.

In the film, School of Rock, Jack Black draws this diagram on the chalkboard as a prelude to teaching his students how to be a rock band. I tell my students that my course is about constructing a similar chart for contemporary short fiction—not simply to "label" styles or approaches, but because I want to teach my students how to have a comparative and genealogical conversation.

To that end, we discuss these questions: What is a short story? What circumstances contributed to the form's emergence and evolution? How did certain rhetorical and stylistic features (such as ending with an epiphany, the story as "slice of life," the surprise ending, the adage "show don't tell") become maxims and why? How have writers of short stories invented and re-invented the form? In what way do some short stories function both as "story" and as that author's aesthetic credo? What is "the traditional short story," and how did it come to be traditional?

What's your aesthetic?

I practice something I call aesthetic diversity. This approach is grounded in my belief that every apprentice writer is—innately, congenitally, cognitively—who s/he is. My job as a teacher is to facilitate, to help my students discover and determine their own predilections and preferences in terms of aesthetic, form, and even genre.

On the first day of class, I present my students with two quotations and ask which "rings a bell" with them?

William Gass: "What one wants to do with stories is screw them up."

Willa Cather: "I don't want anyone reading my writing to think about style. I just want them to be in the story."

Their answer probably indicates that student's particular aesthetic, what principles of art they value.

When students have strong feelings for or against a particular story or author, I encourage them to consider what this reaction might be teaching them about their aesthetic preferences, about what they value in what they read and write. They learn an important lesson in my class: how to discuss a story that isn't "their cup of tea."

Immersive Mimicry

Students write a series of imitations, which must demonstrate their thorough knowledge of that story's unique signature through mimicry. The first day, I show them this Shawn Mitchell interview with Benjamin Percy in Fiction Writer's Review.

"On occasion, if I truly admired a story, I would scribble out its design in a yellow legal tablet. Paragraph One: Character A introduced in job-related action that reveals personality; Setting at war with character and creates sinister mood; Theme hinted at in last sentence via weather and lighting. And on and on, blow-by-blow, like you said. And then I would try to borrow that skeleton and paste my own flesh upon it, creating an entirely different story with the same beats. That was a great learning experience."

Inspired by this idea, I turned "imitation" into a three-step process:

Step 1: doing a descriptive outline, following Ben Percy's method of describing a story "beat-by-beat" Here's an example of a descriptive outline.

Step 2: an imitation or mashup, etc. a creative response

Step 3: a critical paper about what you learned about the writer/s aesthetic in the process of doing Step 1 and 2, a critical response.

Advice

Remember: immersive mimicry is more about process than product. The stories that emerge from this exercise are often very deliberately similar to the source text. Some students learned the most by doing a kind of madlib with the source texts, mimicking by substitution. Most, however, combined macro or structural imitation (mimicking overall structure of story, scene & summary, paragraphs) with micro or stylistic imitation (mimicking sentence-level decisions, diction, figurative language, but not to the extent of a mad lib).

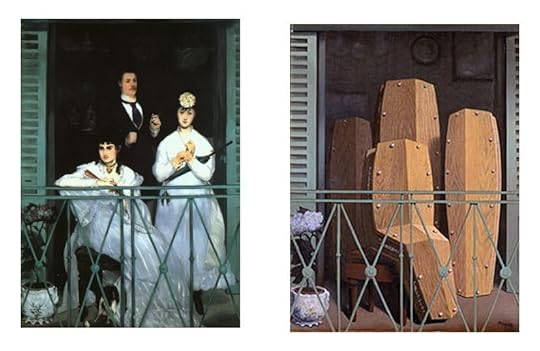

This kind of imitation is encouraged.

But so is this.

Edouard Manet's "The Balcony" and Rene Magritte's "Perspective II: Manet's Balcony"

And this.

A fake Vermeer: "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" painted by Jonathan Janson for the TV adaptation of the Girl in Hyacinth Blue (produced by Hallmark)

Reading List

Here's the reading list. We read between 5-8 short stories per week. We moved fast. I chose to sacrifice the benefits of close reading for the benefits of coverage. Ultimately, my goal was to expand each student's repertoire of short stories.

Edgar Allan Poe, "The Black Cat"

Guy de Maupassant, "The Necklace"

Ambrose Bierce, "Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge"

William Faulkner, "A Rose for Emily"

Shirley Jackson, "The Lottery"

O. Henry, "The Gift of the Magi"

Tobias Wolff, "Bullet in the Brain"

Sherwood Anderson, "Hands"

Anton Chekhov, "The Lady with the Pet Dog"

Ernest Hemingway, "Hills Like White Elephants"

Ring Lardner, "Haircut"

Willa Cather, "Paul's Case,"

John Steinbeck, "The Chrysanthemums"

John Updike, "A&P"

Cynthia Ozick, "The Shawl"

William Gass, "In the Heart of the Heart of the Country"

Robert Coover, "The Babysitter"

Margaret Atwood, "Happy Endings"

Grace Paley, "Conversation with My Father"

Donald Barthelme, "A City of Churches," "The School"

Cris Mazza, "Is it Sexual Harassment Yet?"

Ernest Hemingway, "Soldier's Home"

Raymond Carver, "Are These Actual Miles?"

Mary Robison, "Pretty Ice"

David Leavitt, "Braids"

Amy Hempel, "In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried"

James Baldwin, "Sonny's Blues"

Tillie Olsen, "I Stand Here Ironing"

Barry Hannah, "Testimony of Pilot"

Ethan Canin, "The Year of Getting to Know Us"

Andre Dubus, "A Father's Story"

Ron Hanson "Wickedness"

Dan Chaon "Big Me" and "Falling Backwards"

Stuart Dybek: "Pet Milk" and "We Didn't"

Jayne Ann Phillips , 4 flash stories from Black Tickets

Tina May Hall, The Physics of Imaginary Objects

Richard Yates "The Best of Everything"

Joyce Carol Oates, "Where Are You Going? Where Have You Been?"

Lorrie Moore "People Like That are the Only People Here,"

Charles Baxter, "Gryphon"

Ben Percy, "Refresh, Refresh"

John Cheever, "The Swimmer"

Rick Moody "The Grid"

Russell Banks, "Sarah Cole: A Type of Love Story"

David Foster Wallace, "The Depressed Person"

Jennifer Egan, "Great Rock & Roll Pauses by Alison Blake"

Flannery O'Connor, "A Good Man is Hard to Find"

Sherman Alexie, "This is What it Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona"

Junot Diaz, "Fiesta, 1980"

Gish Jen, "Who's Irish?"

George Saunders, "Sea Oak"

May 8, 2011

A Novel Graduation Story

Sherrie Flick & Ben Gwin, MFA graduation 2011

This week, I've invited my friend Sherrie Flick to describe the novel workshop she taught this past semester at Chatham University, and my former student Ben Gwin to talk about being a student in that course. A little backstory: in the fall of 2006, Ben was a student in my senior seminar in fiction at the University of Pittsburgh. I talk more about that class here. Ben started his novel, his Big Thing in my class, then kept writing, and was eventually accepted into the MFA program at Chatham University. Now he's getting ready to graduate, and Sherrie is his thesis director, and she's been keeping me updated on Ben's progress and that of another former student of mine, Rich Gegick.

Points of View: A Dialogue Between Student and Teacher

By Sherrie Flick and Ben Gwin

SF: This semester I taught a novel writing workshop for the MFA students at Chatham University in Pittsburgh. My goals for this class were four-fold: Generate writing. Learn craft. Make progress as a group. Think and talk about novels, applying the discussions to the work at hand.

I wanted the class to operate less like a workshop and more like a studio (thinking toward a visual arts model, where craft and practice and modeling are pursued/explored actively each class).

The first 4 weeks of class, the students had intensive writing time. I asked them to write 400 words a day. I collected word counts at the end of each week via emailed Word docs. I didn't read this work, so much as verify the counts.

During this time I also asked the students to write 1-page proposals for their semester-long projects (50 pages of a novel), due week two. I rejected most of the proposals and asked for revisions and then reread and approved or asked for more revisions. Students also selected an author of their choice to read in those first four weeks. They read a first book and then a later book by that person. I wanted them to see how a first book works and how a writer matures into later work.

All of this was month one. No workshopping, no meeting up as a class—just reading (4 books) and writing (8,000 words) and proposing. Practicing, in a sense, being a writer.

BG: My initial proposal was rejected I kept muddling my goals for the course and overlapping them with my thesis class (which I took concurrently)and the novel workshop, I had to separate the two. My goals changed so I revised my proposal to match the outcome of the work I produced for the class. I had hoped to use the novel class to get feedback on the section of the manuscript I was having the most trouble with (pgs 150-200) and then get the whole manuscript revised by the end of the term, but that didn't happen.

Instead I used the class to complete a whole rough draft, then for my final I revised 50 pages of the manuscript following the 135 pages I turned in for my thesis. I figured this would benefit the novel the most.

SF: Proposals were accepted/rejected based on the goals set forth by the student for the project. If a student didn't articulate his/her project or had goals that were vague or unachievable in the scope of a semester, I asked the person to rewrite after giving some guidance. The proposals outlined what the creative work would be and defined the project for both the student and for me.

BG: Coming into the class, I had already written an almost finished, beginning-to-end (very rough) draft of Clean Time, a novel-length manuscript, which I started in 2006 at Pitt with Cathy. By almost finished, I mean I'd written the first half and the last quarter, and a list of scenes I needed to complete. So, I spent the first month of novel workshop bridging this gap. I generated new stuff in the morning and revised old stuff at night.

The 4 weeks at the beginning were beautiful. I wrote a lot read Angels and Already Dead by Denis Johnson and studied them. I wrote a craft paper on how Denis Johnson uses dialogue to characterize and move plot. I also studied how he weaves description into action and discussed the Macro structure of the two novels. I did my best to implement these craft elements into my story.

I set out to address my weaknesses and to generate the missing scenes and was successful on both counts. I feel like I'm dealing with better problems now. I have 65,000 words, and I'll be able to cut a lot of it and rewrite with characters who are more real.

The best part of my last year of school was that my professors; Derek Green, Marc Nieson and Sherrie all took a great interest in my work and helping me get it to the point it can be published (eventually); they treated me like an apprentice not like a student, in that I was more concerned with improving my writing than getting grades, and they let me tailor my assignments to my larger project.

SF: What I wanted in weeks 5 through 15 was an active class (think art students painting each week in front of easels, trying out/learning, experimenting with different techniques). Each student had 5 pages of work due each class.

During the first and last class meetings each student read their five pages aloud, and the class gave feedback in the moment, after hearing the work. These public-reading workshops created a nice intro and then closure to the semester. The rest of the semester's Wednesday evenings every student turned in five pages in advance and the class critiqued the pages (50 in all) for the next workshop.

In class the students broke into small groups (3-4; there were 11 students in the class) to discuss the pages, with each student given 7 minutes/25 minutes of total workshopping time. We then gathered back into a large group for more discussion.

The five pages themselves were not randomly selected, however. Each week, I chose a craft element: dialogue, plot, characterization, setting, significant object, point of view. The students selected work (often from their first-four-week generation pages) that highlighted the element selected.

In this way, the entire class focused on the same idea, could discuss the same craft elements in a range of work, each week. I wanted the students to learn to talk craft on a higher level, to learn from their peers in regards to elements they might be weak in, to teach others when they were strong. I wanted the class to move forward, learning from each other.

BG: Focusing on one craft element was key and produced discussion revealing how interlaced all the elements are in a good piece of fiction. This may be obvious. I'm not a great public reader so it's good for me to have opportunities to practice reading out loud.

Craft discussion is fun, especially as I get a better grasp on how to implement it in my own work. Like I paid more attention to detail in revision, to the right details, not just getting a sentence to sound nice or smart, but improving the prose to further the story through showing character and advancing action. This is probably also obvious, but I struggled with some really obvious things and now I at least know what they are, like plot.

SF: Since the weekly five pages focused on craft elements, the workshop discussion was directed, in that the students discussed what was and was not working, let's say, with dialogue. The students had a basic idea of what each other's projects were about (proposals were posted on Moodle–which is like Blackboard) and they could also ask questions of the authors, which they did.

BG: I thought the balance was good between the immediate feedback and the small group feedback. It's nice to get unfiltered and immediate "that was really confusing" response. It supplements the more in-depth, close readings of the small sections.

I helped teach students that sometimes you have to cut ten pages and turn it into a paragraph. I keep a folder with everything I cut, (I got this idea from an article Sherrie gave us to read) and it is 8,000 words. And that's just what is worth saving.

Rich Gegick

I think Rich Gegick was the best writer in our class. He writes really sparse, Carver-like prose, which I don't tend to do naturally. So reading his stuff helped me a lot on a sentence level. I gravitate towards writers who are better than me and doing interesting stuff and badger them into telling me how they make their words so good. I recommend this.

SF: Workshop classes at Chatham run three hours once a week (6:30-9:30pm). These long classes allow time for thorough discussions and for a variety of activities. At the beginning of class, sometimes I passed out a different novel to each person (from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein to Mary Gaitskill's Veronica) and had everyone read their book's first sentence and discuss its purpose, success.

Other times I copied the opening pages of a novel for everyone (Jonathn Lethem's Motherless Brooklyn, for example) and we read those aloud, each student taking the next sentence in turn. In this way, we could hear good, varied sentence structure, hear strong voice, discuss how the opening of a novel works—what it presents and why, and then talk about theme, tension, action.

Other days, I worked with the class on micro elements: sentence revision, dialogue techniques. We revised the (bad) sentence "She was carving the turkey" more times than I'd care to remember.

How this exercise works: I'll ask the class to revise the sentence to be about a dysfunctional family in Florida (without using the words "dysfunctional" or "Florida" or "family"). Students throw out suggested revision ideas and we rewrite the sentence as a group. This process helps students use active language and encourages them to practice the subtle and wonderful and exciting art of showing not telling. Then I'll ask them to rewrite this same sentence so that it's Thanksgiving in the South and the main character is a prostitute named Glenda.

BG: Glenda chased her penicillin with vodka, opened a window and stuffed cornbread into the hollow turkey.

SF: One day we were talking about unnecessary directions in sentences, like: "She sat down in the chair and turned to watch TV." So, I pointed at Ben and said, "Ben is in the den. How do we get him to the kitchen without using the words 'he walked down the hall'?" Then, we brainstormed for a long time how to do this, and we failed, and then I gave it as a take-home assignment and now I ask people in bars to solve this problem. It's fun.

BG: I woke up on the living room couch shaking so bad that I spilled coffee on the kitchen floor and burned my hand when I poured it.

SF: All of this revision activity served to show students that micro elements in a novel, in any writing (words, sentences, paragraph breaks, openings, chapter endings) are something they should practice in order to get to the bigger, macro issues of theme, content, tension, action.

In these beginning-of-class discussions I tried to let the second year students inform the first-year students as much as possible, tried to set up micro and macro mentoring in that sense. I like to think of fiction on those two levels: micro and macro. I used the excellent craft book The Artful Edit by Susan Bell to reinforce those ideas.

BG: What helped me immensely was following Cathy's advice that I bring a project with me to grad school. The three years I spent pre-MFA, and the first semester at Chatham, really just got me to the point where I understood my protagonist and the story.

If Professor (Aubrey) Hirsch (who saw the first grad school excerpts of Clean Time in her workshop in fall of '09) were to read my thesis, I think she'd be surprised (and delighted) at how little it resembles the first drafts.

I suppose the downfall of the novel workshop is that students might not continue working on the ideas they generated for class. I mean the end result can't be a 50 page assignemnt, but rather a 50 page jumping off point. Of the first 150 or so pages I wrote before grad school, probably 10 made it into the 300 page manuscript I have now.

Maybe having an assignment to outline the rest of the story as part of the next novel workshop would be good?

SF: Also, over the course of the semester I set up one-hour conferences with each student to review 25 pages. In this way, I was pretty engaged with each project and could watch as it unfolded and give advice and reading suggestions along the way.

All in all, I'm happy with this novel workshop model. I would like to try it again with this same syllabus. I think the initial four weeks of required writing and proposal creation and intensive four-book readings helped the class's success in that no one came into workshop cold—everyone had at least 8,000 words in hand, a specific idea of what they wanted to accomplish for the semester, and an author (or two) to serve as models.

Like Ben, many students completely changed (and rewrote) their proposals as the class advanced. They dropped characters, changed verb tense, altered point of view, condensed scenes, expanded scenes, and changed character motivation in their novels. This, to me, shows good progress. Students learned that writing a novel isn't easy or neat, that it's a messy process that involves a lot of letting go and then thinking hard and then: writing. They dove into the messiness of it and came out with knowledge about where to go next.

One last thing: Ben is in an excellent place right now as he finishes up his MFA and heads out into the "real" world with a solid manuscript draft and the skills and motivation to polish it into a real book.

Bios

Ben Gwin graduated from University of Pittsburgh with a BA in English/Writing and just finished his MFA in fiction at Chatham University. He is hard at work on his novel, Clean Time. This summer he'll attend the Juniper Institute at UMass Amherst.

Sherrie Flick is a Lecturer in Chatham University's low-residency and residency MFA programs. Her debut novel, Reconsidering Happiness (Bison Books) was a semi-finalist for the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award. She is also the author of the award-winning flash fiction chapbook I Call This Flirting (Flume)

Cathy, Rich, and Ben in 2006. This was taken in James Simon's studio at the Gist Street reading series, which means that Sherrie Flick is somewhere in the room, completely unaware that she's going to advise Rich and Ben's theses. Weird, huh?

May 1, 2011

The Novel Club

Last week, I talked to Kim Barnes, who teaches a novel-writing course. This week, I'm talking to students who've taken (or are about to take) that course at the University of Idaho, a program which regularly offers a year-long novel workshop capped at six students.

Last week, I talked to Kim Barnes, who teaches a novel-writing course. This week, I'm talking to students who've taken (or are about to take) that course at the University of Idaho, a program which regularly offers a year-long novel workshop capped at six students.

Did you need this course in order to write a novel? If it hadn't been offered, or if you'd ended up at a different program, would you have written your novel anyway?

Anesa: The pages I produced for Novel Workshop became part of the third novel I've written (the previous two still unpublished but dreaming of resurrection). So it's likely I would've written the novel I recently completed even without the support and structure of workshop. It also would probably have been a longer and more agonizing process.

Annie: I came to the program with a novel in mind, and a short start to it, but without this class I think it would have taken me 15 years to actually write it. The process was completely overwhelming–all those blank pages yawning for miles ahead. It took the prod and encouragement of a concerted novel class for me to really put myself to it and risk the failure.

Jerry: My primary desire was to write the novel, so I would have written one. It just wouldn't have been this one.

Andrew: I entered the MFA program knowing that I would have to write a novel, if not for the program then for myself. If we hadn't gotten this class off the ground, I would still be chipping away at the novel I brought to the novel class the first semester – an anemic, plotless, themeless novel about a boring character. The class changed everything for me, and showed me that throwing away my first 150 pages and starting fresh was the greatest thing I could have done. Sounds terrible, but it might have been the most valuable lesson I took away from the MFA.

What is the ONE THING you learned about writing a novel that the new group coming in absolutely needs to remember?

Annie: Endurance and stubbornness (applied wisely of course!)

Craig: Actually, I took the long-form class during the 2009-10 academic year with novelist/memoirist Mary Clearman Blew. My experience was one, I imagine, similar to that of a lion tamer training a new big cat. Expect to be knocked down. Our class was to show up on day one with a finished 300-page manuscript. Every student was undoubtedly a talented writer, and after having worked exhaustively for the deadline we all had high expectations. I remember, specifically, walking into my workshop ready to knock the socks off of my colleagues with my masterpiece only to leave that little room a few hours later needing a stiff drink. By no means was anyone cruel, but what brought that punched-in-the-gut feeling was the realization that, "I've no idea what I'm doing." The novel was an animal like nothing I'd ever faced, and it took a couple drafts to even understand what I was trying to say, let alone to make it any good. But after one semester we all understood that this was part of the process. After the second semester and two or three brand new drafts later, we came to understand that writing and then re-writing from page one was also part of the process (and that process was probably going to last for a few years). It's been over a year since the course, and I'm still wrestling that lion. It knocks me down, but each time I get up understanding the novel a little better. One of these days, I'll tame it. Until then, I keep writing.

Jerry: I feel that anybody can write 300 pages, but it's quite another to throw them all away and then go back and sift through them for what is salvageable (or not) over a course of years and form it into a compelling narrative and then throw it out again. I have burned my manuscript six times and each of the six times I felt better. So that would be my advice: it's all disposable, but it's all valuable.

Andrew: Jerry is right – to be able to let hours of work go "to waste," especially on a long-form project, is a difficult but valuable ability. Along those same lines, Kim will tell you to kill your babies. She knows what she's talking about, and it applies to the sentence level, the chapter level, or even character and plot level.

Larry: You can write 300 pages and still have no idea what your main character desires, and there's the rub.

How did this class compare to other creative writing classes you've taken?

How did this class compare to other creative writing classes you've taken?

Anesa: In my limited experience, the pitfall of workshops is the tendency for egotism to dominate the tone of discussion. Most of us experience it at one time or another: the impulse to flaunt our own talents and hog the group's attention at others' expense. It doesn't matter that this can be unconscious; even without an intention of breathing up all the air in the room, the pattern is unhelpful. The format of Novel Workshop seemed to insulate us from this corrosive tendency. Maybe it was the luck of the draw, or maybe we realized at a gut level that, given the small group size and significant investment in time and output, we HAD to go the mile to be constructive for each other.

Craig: Unlike previous workshops, the long-form course was an open discussion. The writer was not the silent observer in the room as everyone else spoke of their work. Instead, the writer helped guide the discussion, freely asking and answering questions. This helped incredibly as the discussion wouldn't get hung up on one particular point (or flaw), which can sometimes happen in workshops. The writer could simply say, "I'll work on that, but now can we look at this other aspect that's troubling me?" In our class, that openness made all the difference, especially when there were a few hundred pages of material to work through.

Jerry: What they said, but with horns on it. The intensity and closeness of the group set it apart from anything I've been a part of in school.

Larry: In most fiction workshops, I felt that at any moment somebody might "smash" my work. That's the best way to explain how it felt to me, I can't guess their intent. In the novel class, it felt like an honest but gentle process. The pain was not instilled by others' egos, but by knowing how much more work we ourselves had to do on the novel. If someone in this class said, "I don't get the point-of-view of the narration," it wasn't an evaluation of your worth–as workshops sometimes feel–rather it felt constructive and encouraging, and in the end as if we were all subjects to a higher power called the Novel.

Are you—in the words of NaNoWriMo—a planner or a seat-of-the-pantser or a combo of both? Did you use an outline or storyboard? Meaning, what did you learn about your own particular writing process that you might not have figured out otherwise?

Are you—in the words of NaNoWriMo—a planner or a seat-of-the-pantser or a combo of both? Did you use an outline or storyboard? Meaning, what did you learn about your own particular writing process that you might not have figured out otherwise?

Annie: Without the "forced" writing, I doubt I would have pushed myself to the levels of discomfort I did–the not knowing, the doubts, the confusion, the just downright hardness of it all. Going there over and over again created the kind of familiarity I needed in order to understand the process–my process--and foster the patience to wade through the hours and years, to understand the failings and the successes and be willing to keep working, without taking either too seriously. This is what truly has made me able to "trust the process."

Jerry: Mostly I sit down and rattle shit out and then go back and work in the outline of the rough draft. For my nonfiction book proposal, I sat down and wrote out a complete proposal with chapter outline so I can send it to an agent. So in the words of Forrest Gump: "It's both."

Larry: I write and write and write and love the deadlines. May I please have another deadline? I have enough digressions to fill ten novels I suppose, and still no clear idea about where I'm going except something about a carousel. I trust the process and have faith but it's hard. When I lose faith–which is quite often–I buy myself books on how to structure or outline a novel. They haven't helped much. Life throws you curve balls to test your faith; novels don't, so you have to constantly pitch to yourself, and try to get yourself out.

Did the existence of this course affect your decision to attend this MFA program?

Did the existence of this course affect your decision to attend this MFA program?

Amy: No, I had no idea this course was offered when I applied or accepted. Even though my primary interest is novel writing, I came to the program expecting to spend my workshop time on short fiction, and have to work on a novel on my own time. I'm intensely grateful for the chance to work on the stuff that's most important to me as coursework, instead of on top of coursework.

Jeremy: I also wasn't affected by the existence of this course in choosing to attend UIdaho. I do remember seeing this course on the published schedules of past semesters after I got accepted into the program, and it did interest me a lot. I tried working on the novel I've been re-drafting for several years now in between my other coursework, and I even tried using some parts of it for my fiction workshops. The results usually left me more confused about the novel than I expected though, and I'm beginning to understand that short story workshops aren't conducive to novel excerpts, at least in my case. That's why I'm also excited about the opportunity to workshop a novel, the entire novel, and combine it with talking about how other people write novels, too.

Jerry: Nope.

Terry: I had written novel length fiction before coming to the program, and I had "written a novel" in the back of my mind, but I came to the program thinking I would write a collection of short stories or short stories and a novella, as I had done before. That said, I definitely became excited when I heard about the novel writing class, though it didn't factor in to my decision to come here. I tend to believe in the unconscious trajectory, though, so it strikes me now as entirely logical that I would be in this program at this time and with this set of faculty and students.

For those of you who have yet to take the course, what is your BIGGEST FEAR about writing a novel?

For those of you who have yet to take the course, what is your BIGGEST FEAR about writing a novel?

Amy: Although I've written two (failed) novels before, what scares me about this format is the speed with which I'm going to have to do it. n the past, my process has been to spend a few months drafting what I call a "garbage draft", what some people refer to as the "zero draft" — basically, getting all my ideas on paper, finding out who my characters are, and what the shape of the story is going to be, but not worrying about it being at all readable, let alone *good*. This draft is written mostly in notes and questions to myself — "but why would she do that? what might happen if she did this instead?" — and is free to contain any number of false starts, alternate versions of scenes, snippets of dialogue with no context, etc. Once I have this down, I go through and turn it into a draft that at least looks like a story with scenes and narration and whatnot, and makes cohesive sense, even if it's still not any good. In the next draft, I start working on things like voice, description, language, and nuance — only after this draft, am I ready to show it to my first readers. All this takes a little under a year. Obviously this time I'm going to have to produce a readable, and preferably a "good" draft in much less time than that, and I'm really not sure how I'm going to do it. That's scary. On the other hand, I make no claim that my old method brought me any great success, so I'm hoping that the requirements of this class will force me to tinker with my process in a productive way.

Jeremy: I am most afraid of not being able to oscillate between the reader feedback I want and will now have and my own vision of the novel. Which one of us is right? Is it me, with this idea, or my classmate, with this other, perhaps more reasonable, idea. I'm afraid I can't combine the suggestions of my classmates for improving my novel with the way the novel already is without completely losing track of the whole thing and watching it fall apart. I hope to learn how to keep it all going, the novel, the thinking about the novel, the incorporation of feedback on the novel.

Terry: My biggest fear is that I will not honor the story. This is always my fear. I can come up with a draft that seems interesting or that has a sense of itself, but I have noticed that often it has little to do with what the story itself may need. I get in the way with my agendas and conscious motivations, or the characters seem too foreign, and I want to make them more comfortable for myself. The struggle is to let the characters be what they want to be in this story and to let myself, as writer, embrace them and get to know them as they need to be.

Did you pursue an MFA degree because you wanted to write a novel? Did you go to grad school with a particular book project in mind, even just a general idea in your head? Or were your goals not as specific as that? (Any answer is fine—people go to grad school for many reasons.)

Did you pursue an MFA degree because you wanted to write a novel? Did you go to grad school with a particular book project in mind, even just a general idea in your head? Or were your goals not as specific as that? (Any answer is fine—people go to grad school for many reasons.)

Anesa: Yes, I intended to expand a short story I'd written several years before into a novel. When I applied to the program at U of Idaho, it was my hope to make this my thesis project. At that time, I'd heard nothing about a workshop on novels being offered.

Amy: My primary reason for doing an MFA was to improve my writing. I had taught myself a lot by writing two novels, but I felt like I had reached a plateau, and that I needed an external structure to push me harder. I figured that writing short stories would help me with craft, and that I could apply that to novels — and I guess that has been both true and not true. I have gotten a lot out of my short-form workshops, and they have made me a better writer. But I'm confident that the novel workshop will address issues that are simply beyond the scope of a regular workshop.

Jeremy: Like Amy, I too feel that workshopping short stories improved my writing skills. I have more tools in my toolbox than I did before–far more tools, actually. Before coming here, though, I didn't realize how little I knew/know about writing the novel. I've had practice reading and writing short stories far longer than I've had doing the same with novels. I'm, comparatively speaking, a novel neophyte. I was talking with my creative writing professor from undergrad, asking him which I should focus on as it comes time for me to pick a thesis project (I'd always assumed I'd use my novel,) and he asked me which, the novel or the short story, do I feel most confident in. In looking at it that way, it was obvious to me that it was the latter. For some reason, I hadn't considered before how little practice I've had on the former, how unsure of myself I am on it.

Jerry: Yes. No. And I did want to write across the genres. And because it came up: I think writing short stories to teach you to write a novel is like saying playing American football will teach you to play soccer. Sure. Keep running and it will build your cardio.

Andrew: Again, to play off Jerry, cross training only gets a person so far. Studying the craft of short story writing isn't a waste of time for would-be novelists, but it doesn't cover all bases (too many sports analogies). This might sound a little basic, but a novel is not a long short story. It's not sitting at the computer for longer, typing more words. It's thinking about more elements at once. I came to the MFA program with short fiction experience, and it didn't magically translate to novel writing until I saw the novel as a different task.

Larry: Well, I want(ed) to write a novel. But my main goal was to finish a story, any story, a short story even. And I did, hooray! I published one and I've finished two more, and sent them out. The novel, well, no pun intended, but that's a whole 'nother story.

Terry: I entered the program to continue the momentum I had developed as an undergrad writing a creative thesis of short stories and a novella. I specifically wanted a program with a less competitive atmosphere among students, and one that encouraged cross -enre writing. I had experienced the benefits of a good mentor/student relationship with my undergrad thesis advisor, and I hoped to continue that kind of relationship here. I thought I would continue to work with short stories and possibly essays, but I wanted to work on craft very particularly. I am surprised to find myself interested in writing a novel for my thesis.

How dedicated were you/are you to the important task of helping others write their novels in relation to the equally important and sort-of-enormous task of you writing your own? In other words, why write together, when reading other people's stuff will probably just slow you down?

How dedicated were you/are you to the important task of helping others write their novels in relation to the equally important and sort-of-enormous task of you writing your own? In other words, why write together, when reading other people's stuff will probably just slow you down?

Anesa: I have found that when we share work with a small group of fellow writers, especially if we put the critical faculty aside at least at first, we can experience literature in a way that's possible nowhere else–at its first inception, where it may be cautious or incautious, a wallflower or an exhibitionist, wise or foolish or hyper or grandly unconcerned. But definitely not to be missed.

Amy: You learn a lot more from critiquing than being critiqued, and I believe that. Anyone can say "this isn't working," but being forced to identify precisely what isn't working, why, and how it might be fixed ultimately teaches the critic as much about craft as the author.

Jeremy: When I was a member of the community college jazz combo, in another town, I learned a lot about how art is a community of people who, at its best, wants to contribute to the bettering of that community, to the persons within it. When we engaged in improvisation, we weren't, or shouldn't have been if we were, improvising for our own selves, for the betterment and enjoyment of our selfish egos. I learned that improvisation in jazz music is the most about reaching someone. Jazz is a conversation, our professor (and combo piano player) said to us. If a jazz combo is a microcosm of the artistic community, and I think it is, than it teaches us that we each get our say, with equality, but that we are also all working for the same goal. Encouragement beats discouragement–it beats it every time, I've found, but that's my situation. A supportive jazz combo gets me to go home and practice my scales, with fervor. A discouraging jazz combo gets me to go home and want to throw my horn in the river (and not practice anything.) That's why I feel it's important to be a part of this writing group; I can appreciate the value of encouraging feedback, how an artist might actually need it in order to keep creating. Receiving encouragement and support is what I want as an artist. To me, it makes sense that I participate in the world of writing by offering some encouragement of my own.

Craig: We read each other with a passion because ultimately we learned from all the mistakes that others had made. Our group frequently continued the workshop discussions after class, having drinks or going out to dinner, still talking about how to improve those manuscripts. We talked about each others' projects like most people bring up the weather. The group seemed necessary for surviving the novel during those early stages. Reading their manuscripts inspired me, leading me to better and better writing.

Jerry: What they said and, as we say in fire: You don't know it until you have to teach it in the field. There are no shortcuts.

Larry: From a purely selfish perspective, you learn from editing and critiquing others, even if at the time, you feel like you have no idea what you are saying. You finish the program and you wake up and realize that although you still have a long way to go, you can absolutely give yourself constructive and helpful criticism without always having to rely on others.

Terry: The community of writers, at all levels, is a dynamic, transformational force. I feel privileged to have readers, and I feel equally responsible to read their work. As I read, I learn to read more effectively, and as I comment, I have to question my assumptions and my prejudices. If all I ever read was my own work, I would be the same sorry writer I was ten years ago. Yes, the work of writing is labor intensive, and so is the work of reading others' writings, but I don't think we walk alone. Ever. Period.

I want to thank these writers for sharing their experience with the readers of this blog and commend them for sharing their wisdom with each other.

I want to thank these writers for sharing their experience with the readers of this blog and commend them for sharing their wisdom with each other.

A native of Wichita, Kansas, Anesa Miller holds a Ph.D. in Russian Language and Literature, which she taught on the college level for some 12 years. She has published poetry, short stories, essays, and translations. She completed the MFA in creative writing at the University of Idaho in Spring 2011.

Amy Danziger Ross is currently working toward an MFA degree at the University of Idaho. Her work has appeared in the Journal of Microliterature, DIY Magazine, Hatch Magazine, and Providence Monthly. She is originally from Providence, RI.

Jeremy Vetter grew up in the forests and mountains of Newman Lake and North Idaho. He received his MA in English from Central Washington University. In the Sonora Review, he published a piece nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He attends the University of Idaho, where he is an MFA candidate in fiction.

Annie Lampman grew up in the woods of Idaho where she taught her three sons to run feral. She has an MFA in fiction (2009), teaches writing at the University of Idaho, fields teen dilemmas, and coaxes a fearful African Grey parrot to give kisses. Her work was recently awarded a Pushcart Prize special mention.

Craig Buchner received his MFA (fiction) from the University of Idaho in 2010. His work has appeared in Puerto del Sol, The Pisgrah Review, Word Riot, and others. In 2006, he won the AWP Intro Journals Award for fiction. He currently resides in Portland, OR, and teaches writing at Portland Community College.

Terry Lingrey is an MFA candidate at the University of Idaho. Her work has appeared in Main Street Rag and Scribendi. She was raised in England, Germany, and the United States, and consequently feels perpetually homeless. Before she became a writer she was a riding instructor, horse trainer, and equine massage therapist for twenty years.

Jerry D. Mathes II is a Jack Kent Cooke Scholar alum, publishes in numerous places, fights wildfire on a helicopter-rappel crew during the summer, and taught the Southernmost Poetry Workshop in the World at South Pole Station, Antarctica. He loves his two daughters very much.

Andrew Millar received his MFA from the U of Idaho in 2009. He has published short stories and poetry, has edited a lit journal, and currently edits and writes for a sustainability news website. His band is called The Free Sweets.

The son of Polish Holocaust survivors, Larry N. Mayer grew up in the Bronx, NY. His first book, Who Will Say Kaddish?: A Search for Jewish Identity in Contemporary Poland was published in 2002. His first short story, "Love for Miss Dottie," was selected for publication in the Best New American Voices 2009 anthology. He lives with his wife, two daughters, six chickens, two bunnies, one chihuahua, one anole, and 10,000 honey bees in Cambridge, Mass.