Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 12

November 13, 2024

Join next week's Q&A for "How to Think Like Socrates"

My new book, How to Think Like Socrates, will be published next week (19th Nov) in the US, Canada, and some other parts of the world. There’s still time to preorder your copy, either in hardback, ebook, or the audiobook that I narrated myself. (If you’re interested in getting a signed copy, you can preorder one from Porchlight — they will ship internationally.)

Once you have done so, you will be eligible to register for our free Q&A session on Zoom, which will take place on publication day. Just enter your details in this short online form to register for the Q&A session and claim your other rewards.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

List of FreebiesJoin me for an exclusive live Q&A on Zoom where we'll dive deeper into the book. Tues 19th Nov at 6-7pm Eastern Time. NB: A recording will be available for playback if you're not able to attend.

You will also receive a link to download our illustrated PDF booklet titled A Guide to How to Think Like Socrates, with original artwork by Stan Yak, and graphic design by Sara Beth Haring.

Enjoy 6 months of full access to my Substack newsletter, packed with insights and exclusive content.

Gain access to bonus audio and video interviews, offering unique perspectives on the book.

Terms and conditions. All orders placed before Nov 19th are eligible. You must submit your details using the online claim form on this page. The bonus content will be sent to you using the email you provide. If you are already a paying subscriber to my Substack newsletter, you will receive a complimentary six month extension. Details of this offer may be subject to change without prior notification.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 12, 2024

Book Review: Stoicism, A Very Short Introduction by Brad Inwood

Brad Inwood is professor of philosophy and classics at Yale University. He is the author, or co-author, of several academic works on Stoicism and other forms of Hellenistic philosophy, including The Stoics Reader: Selected Writings and Testimonia (2008), an invaluable resource for anyone interested in early Stoicism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

His latest book, though, applies his scholarly credentials to the task of providing a short layman’s introduction to the subject of Stoicism. First of all, I’d like to say that I recommend this book to anyone interested in learning about Stoicism. It’s a great little introduction. There are more books and articles appearing on Stoicism now, many of which can be quite unreliable. However, this is an authoritative introduction written by an academic philosopher and classicist specializing in the subject. Inwood gives a balanced overview of Stoic Ethics, Physics and Logic. As he describes, Physics and Logic are areas of Stoicism often neglected by modern students of Stoicism. It does perhaps become slightly more “academic” in places, which might not suit everyone’s tastes. This is inevitable to some extent, though, especially where he’s attempting to explain concepts in ancient logic. Nevertheless, overall, I think most intelligent readers will follow this book and benefit from it as an introduction.

Because he’s writing for a wider audience, Inwood also discusses the current resurgence of interest in Stoicism. He mentions my writing and the work of the Modern Stoicism organization, of which I was a founding member, as well as others who have been involved with our work on Stoicism or who are part of the wider movement, such as Ryan Holiday and Lawrence Becker. For example, referring to the modern-day growth of interest in Stoicism as a guide to self-improvement he writes:

Some relatively recent books underline the point: Elen Buzaré’s Stoic Spiritual Exercises (explicitly building on the work of Pierre Hadot) and Donald Robertson’s Stoicism and the Art of Happiness (the author is a psychotherapist specializing in cognitive-behavioural therapy and has published an essay in Stoicism Today: ‘Providence or Atoms? Atoms! A Defence of Being a Modern Stoic Atheist’). Add to that The Daily Stoic website and the book of the same title by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman offering sage advice for every day of the year and it seems that Stoicism is all around us.

That brings me to one of the central questions that Inwood raises in the book. The vast majority of people today who embrace Stoic ethics as a guide to life have little or no interest in ancient Stoc Physics and Logic. These are topics still being researched by academic philosophers like Inwood but they’re largely neglected by modern followers of Stoicism and the self-improvement literature in this area.

What About Stoic Physics and Logic?In Stoicism and the Art of Happiness, I stated my belief that Stoic Ethics can be of value today without belief in the dogmas of ancient Stoic Physics or studying Stoic Logic. Inwood points out that some of the earliest and most influential authors to have influenced the modern resurgence of interest in Stoicism as a guide to life also placed more emphasis on the practical applications of Stoicism than upon the ancient theories underlying it:

[Pierre] Hadot is at times quite frank about his belief that the underlying theories don’t matter to philosophy as a way of life, claiming that the spiritual exercises come first and the doctrines are worked up later to support them (Philosophy as a Way of Life, p. 282). [James] Stockdale doesn’t even mention underlying doctrines in physics, logic, and ethics—he wouldn’t have found any in the Handbook and it served his purpose well just as he remembered it.

Inwood notes that the early Greek Stoics appear to have stated that Ethics, Physics and Logic were closely interconnected. (At least some of them, we’re told, which arguably implies that other Stoics may have disagreed with this.) However, the bulk of the surviving Stoic texts come from the Roman Imperial period, several centuries after the school was originally founded. The “Big Three” Stoic authors most people are familiar with today are Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Their works focus primarily on applying Stoic ethics as a guide to life. They do mention other aspects of Stoicism – Seneca wrote about Stoic Physics to some extent – but most of their surviving writings focus on applying ethics. That has perhaps contributed to the modern perception of Stoicism as primarily an ethical discipline, and the closely-related conception of it as a psychological therapy. These writings also represent the most accessible aspects of Stoicism. By contrast, most of the evidence relating to ancient Stoic Physics and Logic is fragmentary and more abstract or technical in nature, requiring greater scholarly effort to interpret.

We get the sense from Marcus that technical expertise in logic and metaphysics is dispensable for the true Stoic.

Inwood notes that even these three Stoics appear to place varying degrees of importance on the more theoretical aspects of philosophy.

[We get the sense from] Marcus that technical expertise in logic and metaphysics is dispensable for the true Stoic. In general, where Marcus encourages the idea, adopted enthusiastically by Pierre Hadot, that the fundamental message of Stoicism, a moral creed, is somehow independent of physics and seriously argued theoretical enquiry, Seneca does just the opposite.

Inwood notes that although scholars are still fascinated by the fragments on Stoic Physics and Logic, for most people today “it would be hard to make the case that learning the details of ancient Stoic cosmology or mastering Chrysippus’ syllogistic theory would be part of a plan for living a better life, for achieving happiness or balance or contentment.”

Large Stoicism versus Minimal StoicismInwood argues in this book that even early Greek Stoicism, in a sense, accommodated this sidelining of Physics and Logic. From the time of Zeno, the founder of the school, Stoicism appears to have been divided into at least two distinct strands. Zeno taught a threefold curriculum based on Ethics, Physics and Logic but one of his most famous students, Aristo of Chios, rejected the value of studying Physics and Logic. Inwood calls this the Minimal Stoicism strand. About a generation later, Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoic school argued for a broader and more scholarly approach, which came to exemplify the reinvigorated Large Stoicism branch of the school, as Inwood calls it.

Modern Stoics aiming primarily to improve human lives through moral betterment, setting aside physics and logic, can see themselves as the heirs of Aristo’s tradition, one that goes back to the early days of the school. It’s not just our modern reliance on Marcus, Epictetus, and Seneca that feeds this movement; a narrow focus on ethical improvement is also an authentic component of ancient Stoicism.

So modern Stoics, according to Inwood, are in good company in this respect and stand in a tradition that formed an important part of the early Greek Stoa before the time of Chrysippus. Indeed, the historical evidence suggests that after the death of Zeno, for a time, Aristo’s relatively agnostic and “minimal” approach became the most popular branch of Stoicism. Aristo, teaching at the Cynosarges, attracted much larger audiences, than Cleanthes, Zeno’s official successor, who taught at the Stoa Poikile, in the Agora.

Moreover, as Inwood observes, although Aristo’s Minimal Stoicism was later eclipsed in popularity by Chrysippus’ Large Stoicism, it certainly didn’t disappear without a trace. His influence was felt throughout the entire history of the ancient Stoic school, right down to the time of Marcus Aurelius, almost five centuries later. Indeed, one of Marcus Aurelius’ private letters suggests that he became fully converted to the life of a Stoic philosopher after reading Aristo’s writings. If that’s correct, it would help to explain his relative lack of interest in Stoic Physics and Logic.

Nevertheless, Inwood wrestles somewhat with this question as to whether or not philosophers who insist that the goal of life is to live according to nature could ignore the study of nature. How else, he asks, can we know what to follow? And how can we embrace reason and philosophy as a way of life without studying at least some logic?

A modern Stoic, then, might well be missing something if they are too steadfastly devoted to Minimal Stoicism or to practical ethics alone. Here, then, there are interesting questions to ask about the relationship between our two ways of engaging with Stoicism. How much of ancient Stoic logic does the modern Stoic need? Arguably none, as long as they are dedicated to living a fully rational life and have embraced today’s current best canons for reasoning as a guide and constraint. To the extent that Stoic logic played a supporting role in the ancient school we should be able to replace it with modern theories and practices of reasoning—as indeed many modern Stoics in practice do.

He could have added that the ancient Stoics held up earlier philosophers such as Socrates, Diogenes the Cynic, Heraclitus, and Pythagoras as near sages, although none of them studied formal logic. Indeed, Diogenes and the other Cynics, despite being held in very high regard by Epictetus, for instance, were notorious for sneering at and completely eschewing the formal study of logic.

Ancient Stoic physics, then, is clearly obsolete and no reasonable person can believe in it anymore.

Things are more complicated, Inwood admits, when it comes to the question of Stoic Physics.

Ancient Stoics, from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius, thought of ethical progress within the context of a natural philosophy that rested on a kind of cosmic holism, deterministic and providential, guided by a divine intelligence with which human beings need to align themselves. Stoic physics claimed that humans have access to a godlike rationality which mirrors the reason that runs the world, that as a species we are superior to everything else in nature, that all other animals exist to serve our interests. All of nature is made of four elements (earth, air, fire, and water) and consists of a unique and finite cosmos with our earth at the centre. And so on. Ancient Stoic physics, then, is clearly obsolete and no reasonable person can believe in it anymore. (italics added)

Modern Stoics, he says, surely cannot aspire to follow ancient Stoic Physics and theology in their daily lives! Inwood thinks “no reasonable person” today would endorse ancient Stoic Physics and he concludes that it provides “no fit guide for modern rational life”.

Nevertheless, there are certainly a handful of people around who do claim to strictly adhere to (what they believe to be) “traditional’ Stoic Physics and theology. (Perhaps Inwood is unaware of them.) So I’d qualify that slightly by saying that the vast majority of people today probably don’t agree with the whole of ancient Stoic Physics, or even its most prominent doctrines. The few individuals today who do believe that the universe is governed by a benign Provident being don’t usually refer to him as Zeus, don’t sing hymns to him like Cleanthes, or talk with him in private like Epictetus, and they don’t normally practice ancient divination rituals. Clearly even these individuals feel the need to modify ancient Stoic Physics and theology quite substantially to adapt them to their modern sensibilities.

So modern Stoics may be understood as heirs of Aristo and his ancient followers, who adhered to Minimal Stoicism. However, Inwood wonders whether there’s still a possibility of salvaging a form of Large Stoicism for an agnostic or atheistic worldview by replacing Zeno, Cleanthes and Chrysippus’ belief in a universe ordered by Zeus, the divine father of mankind, with a modern scientific view of nature. He refers readers to the work of the philosopher Lawrence Becker whose A New Stoicism (1998) attempts to provide a contemporary reworking of Stoic Ethics founded on modern logic and scientific psychology rather than ancient theological Physics.

If the fulfilment of a rational human being is to be found in using our reason to understand the world and to navigate our way within that world, then many if not most of us could embrace that aim. The Stoic ‘life according to nature’ could still be with us after all; it’s just that our modern conception of the natural world, our sense of what ‘the facts’ really are, has matured. Perhaps we don’t have to abandon natural philosophy to connect with Stoicism today; perhaps we just have to live according to our current understanding of nature rather than the obsolete cosmology that gave such comfort to Marcus Aurelius.

As Inwood points out, if we did retain the notion of following nature as an adherence to science and facts, we might retain determinism but we’d lose the ancient world’s comforting belief in Providence, the notion that we have a place assigned to us in the universe organized by a benevolent divine plan. “But would the result still be Stoicism?” he asks. His answer is that Becker’s version of Large Stoicism is certainly very different from that of Chrysippus but he leaves it up to the reader to decide if his philosophical project is successful or not.

He concludes that we could just accept ancient Minimal Stoicism and embrace Stoic Ethics without worrying too much about the other parts of the Stoic curriculum. However, Inwood thinks it’s still worth striving for an updated version of Large Stoicism, like Becker attempted, which finds some role, albeit a fundamentally transformed and modernized one, for Physics and Logic.

Even if Stoicism for the modern world were significantly transformed by swapping out an obsolete understanding of the natural world for one based on our current best science, it would, I contend, still be worth doing. The intellectual attraction of ancient Stoicism as we’ve come to understand it in modern academic study lies above all in its integration, in its vision of a way of life rooted in the use of reason to navigate life and fulfil our nature as human beings, in the context of the best available understanding of our place in the world.

This seems to me a very fair and even-handed perspective on the relative merits of embracing Stoic Ethics alone versus trying to replace Stoic Physics, which Inwood considers totally obsolete and anachronistic today, with some version of modern science.

Ancient Stoics believed, and so perhaps may some of us, that the good life is better to the extent that it encompasses everything that we can know about our place in the world. That, of course, is the vision of Large Stoicism, the vision of Cleanthes and Chrysippus, not of the Minimal Stoicism we discover in the philosophy of Aristo. Even for those of us who limit our exploration of Stoicism to Epictetus, Marcus, and Seneca, this should still be the vision that inspires. For despite their apparently lop-sided focus on ethics they were nevertheless all adherents of Large Stoicism, believers in the providentially organized world that passed for the best science of their own day. It would be a lost opportunity if we were to respond to the obsolescence of ancient Stoic physics by pulling in our horns and settling for Minimal Stoicism. If there is any value in the arcane reconstructions of the ancient school for the modern thinker intrigued by Stoicism, it lies in this grand, integrative vision of a good human life, guided by the relentless and unsentimental use of reason in a quest for the best available understanding of the orderly world around us.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 9, 2024

You are invited to a Conversation with Modern Stoicism

Please join me on Friday, November 15, 7:00 PM - 8:30 PM eastern time, when I will be discussing Socrates and Stoicism with Phil Yanov, for the Conversations with Modern Stoicism series.

Conversations with Modern Stoicism is an interactive virtual gathering that provides an opportunity for Stoics around the world to connect, learn, and engage in meaningful dialogue with each other.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The events feature a presentation from a speaker followed by multiple rounds of audience conversations via the Breakout Rooms feature in Zoom.

These events are lively, engaging opportunities to collaborate with others as you pursue your journey into philosophical Stoicism.

I look forward to seeing you there!

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 7, 2024

It is not the man criticizing you that offends you...

CommentaryBear in mind that it is not the man who insults or strikes you that offends you, but it is your judgement that these men are offending you. Therefore, when someone irritates you, be assured that it is your own opinion which has irritated you. And so make it your first endeavour not to be carried away by the external impression; for if once you gain time and delay, you will more easily become master of yourself.

It is not insults that upset us but our judgments about them. This is a specific application of the basic formula we met in passage #5: “It’s not things that upset us but our judgements about them.” Here Epictetus reminds us that this applies to insults. They only really become “insulting” if we choose to view them as important. Our irritation, or offence, comes from our own opinion about what was said or done.

November 5, 2024

Video: Socrates and Self-Help

William asked me “Do you have a problem with self-help?” That’s a great question! Answer: Yes and no. I love self-help books but I also think there’s obviously something fundamentally wrong with the whole self-help industry. Check out the video below to watch our recent conversation.

Therapists today often see clients who have read many self-improvement books — they often describe themselves as “self-help junkies”. Even though they feel as if the self-help books they’re consuming do them good, they still arrive in therapy presenting ongoing problems. (Socrates describes a very similar situation!)

Assessment of therapy clients often reveals that they are using self-help strategies in ways that are backfiring and maintaining their problem, e.g., many self-help techniques can become subtle forms of avoidance — as Albert Ellis used to say: feeling better is not necessarily the same thing as actually getting better.

There are probably no self-help strategies or rules for life that are helpful in every circumstance you will face in life. Modern behavioral psychology has revealed a problem with rule-governed behavior (such as self-help advice) being overly-rigid and insensitive to change in our environment. What works in one situation may backfire in another but some people will continue repeating the same mistakes, expecting their strategies to continue working.

Research also tends to show that coping flexibility is associated with emotional resilience, i.e., the ability to select wisely between a broad repertoire of different coping strategies. Self-help literature seldom teaches coping flexibility, though, but tends to encourage over-dependence on general rules or strategies. We are better to learn to think for ourselves rather than depend too much on other people’s advice, as Socrates clearly realized long ago!

Although, in some ways, Socrates can be viewed as the great grandaddy — or the godfather — of the self-help tradition, he also poses radical questions that strike at the very core of what it has become. In particular, Socrates seemed to think that wisdom should be viewed as a cognitive skill rather than merely a set of rules or maxims. The Socratic Method teaches us to question our assumptions about what is good or bad, healthy or unhealthy, and to become more aware of exceptions to our definitions of virtues, and other general rules of life.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 31, 2024

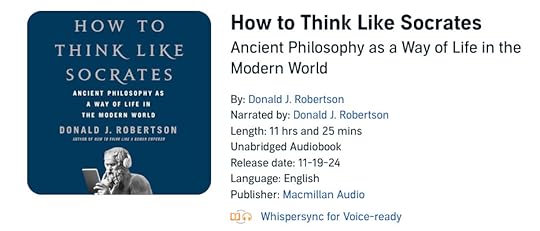

Listen to "How to Think Like Socrates"

I’m delighted to announce that St Martins Press have agreed to give away 25 copies of the forthcoming audiobook of How to think Like Socrates. Just click on the button below to enter your details for a chance to win.

The giveaway is open from October 31st until November 8th. (NB: Unfortunately, this offer is only available to residents of the US but stay tuned for offers in other regions.) The audiobook of How to Think Like Socrates is available to preorder now from Audible and other bookstores.

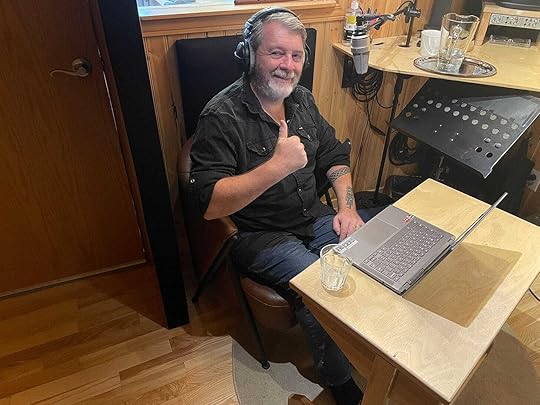

Recording How to Think Like Socrates at D’Aragon studio in Montreal.

Recording How to Think Like Socrates at D’Aragon studio in Montreal.Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

.

October 30, 2024

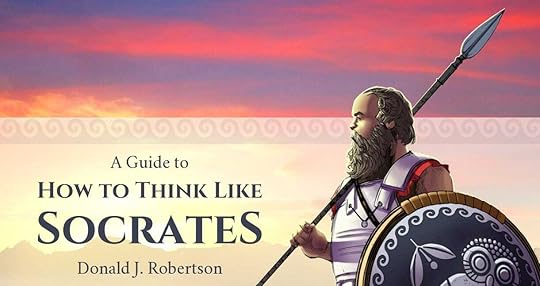

Free Download: A Guide to How to Think Like Socrates

I have just finished creating an illustrated PDF booklet titled A Guide to How to Think Like Socrates, with original artwork by Stan Yak, and graphic design by Sara Beth Haring.

Preorder my latest book How to Think Like Socrates and you'll be eligible to claim a downloadable copy plus other exclusive bonus content. (If you’re interested in getting a signed copy, you can preorder one from Porchlight — they will ship internationally.)

Just enter your details in this short online form to claim your copy of A Guide to How to Think Like Socrates, and the other freebies.

ContentsKey Events – Some of the occurrences that shaped Socrates’ life and thought.

Key Characters – The most important characters in How to Think Like Socrates.

Practical Advice – Summarizing the main self-help techniques described in the book.

What Next? – Suggested questions and recommended reading for further study.

Additional FreebiesJoin me for an exclusive live Q&A on Zoom where we'll dive deeper into the book. Tues 19th Nov at 6-7pm Eastern Time. NB: A recording will be available for playback if you're not able to attend.

Enjoy 6 months of full access to my Substack newsletter, packed with insights and exclusive content.

Gain access to bonus audio and video interviews, offering unique perspectives on the book.

Follow these stepsPreorder the book.

Log into the claim form using a Google account, and complete it.

Wait to receive an email after 20th Nov, with links for your rewards.

NB: You will need a Google account to access the claim form. Dates are based on the US release; you may find the book is published on another date in different countries. If you've already preordered your copy, before reading this, feel free to go ahead and submit your claim form now.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Terms and conditions. All orders placed before Nov 19th are eligible. You must submit your details using the online claim form on this page. The bonus content will be sent to you using the email you provide. If you are already a paying subscriber to my Substack newsletter, you will receive a complimentary six month extension. Details of this offer may be subject to change without prior notification.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 29, 2024

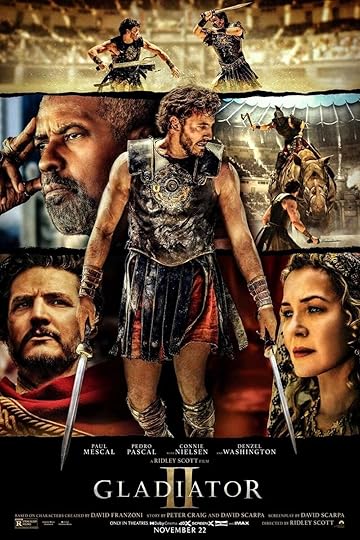

Stoicism in Gladiator II

“The general who became a slave. The slave who became a gladiator. The gladiator who defied an emperor.” — Commodus, Gladiator

This is an update of my earlier article on the forthcoming sequel to the hugely successful sword-and-sandals action movie, Gladiator (2000). Gladiator 2 was directed, like its forerunner, by Ridley Scott. It is reputedly one of the most expensive movies ever made, with some reports of the budget having reached $310 million.

Following the release of the first Gladiator movie there was a sharp increase in public interest in Marcus Aurelius, because Richard Harris portrayed him very memorably in the first act of the movie. A lot of people, who had often never read philosophy before, bought copies of the Meditations, and became interested in Stoicism. We now know that Gladiator 2 is the story of Lucius, the (fictional) grandson of Marcus Aurelius, and that it features Marcus’ daughter, Lucilla. So it’s likely that Marcus Aurelius will at least be mentioned in the movie.

Back in 2006, the musician Nick Cave wrote a fairly surreal script for Gladiator 2 that was perhaps bound to be rejected by the studio. The script for the movie was written by David Scarpa, who wrote Napoleon (2023), All the Money in the World (2017), and The Last Castle (2001).

It’s been reported that Gladiator 2 will continue the story of Lucius Verus II, the young son of Lucilla and grandson of Marcus Aurelius in the original movie.

Of course, Maximus, Russell Crowe’s character, dies at the end of Gladiator. So how can there be a sequel? Well, it’s been reported that Gladiator 2 will continue the story of Lucius Verus II, the young son of Lucilla and grandson of Marcus Aurelius in the original movie. In reality, although Lucilla and her husband Lucius Verus did have a son called Lucius Aurelius Verus, he died young unlike the corresponding character in the movie. Commodus, the son of Marcus Aurelius, is described in the movie as Lucius’ uncle. It also seems that Gladiator 2 will feature Connie Nielsen reprising her role as Lucilla, the daughter of Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Producer Walter F. Parkes has confirmed “It picks up the story 30 years later… 25 years later.” Lucius was a child of about twelve years old in the original, so we can expect to see him in his late thirties or early forties. Given that Gladiator was set in 180 AD, it seems the sequel will be set around 205/210 AD.

Will I be known as the philosopher, the warrior, the tyrant. — Marcus Aurelius, Gladiator

Maximus in Gladiator

Maximus in GladiatorThere’s obviously a fair amount about Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus in Gladiator. It’s not, of course, meant to be entirely historically accurate. Much of the the story is fictional, although many details do correspond with real aspects of Roman history. For example, Russell Crowe’s character, Maximus Decimus Meridius, isn’t real. However, he does bear some resemblance to the real Marcus Aurelius’ senior general during the Marcomannic Wars, Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus.

Seemingly like Crowe’s character, Pompeianus rose from from humble origins to become the most highly regarded general on the northern frontier and a trusted advisor to Marcus Aurelius. Whereas Crowe’s character seems romantically linked with Marcus’ daughter Lucilla, in real life Pompeianus actually married her. Marcus reputedly asked Pompeianus to keep an eye on Commodus after he died but the young emperor abandoned the military camps and returned to Rome, leaving Pompeianus behind. Moreover, like Crowe’s Maximus, Pompeianus was reputedly asked by Marcus to serve as his interim successor, as emperor, not to restore the republic, as in the film, but until Commodus was mature enough to assume the throne. For some reason unknown, Pompeianus refused — like Crowe’s character, perhaps, he was reluctant to assume this kind of power.

In his youth, Marcus Aurelius was also friends with an older Roman general, a Stoic, called Claudius Maximus, who became a mentor to him. Marcus remembers him as being a highly self-disciplined, focused, plain-spoken, and down-to-earth man. Some of his traits appear relevant to Crowe’s similarly-named character:

[I learned from Maximus:] to be master of oneself, and never waver in one’s resolve… to set to work on the task at hand without complaint. And the confidence he inspired in everyone that what he was saying was just what he thought… never to be surprised or discontented; and never to act in haste, or hang back, or be at a loss, or be downcast, and never to fawn on others… To give the impression of being someone who never deviates from what is right rather than one who has to be kept on the right path; and how nobody would ever have imagined that Maximus looked down on him, or yet have presumed to suppose that he was better than Maximus... — Meditations, 1.15

In an ancient novel called The Golden Ass by Apuleius, a contemporary of Marcus Aurelius, the same Maximus is described as a highly disciplined Roman statesman and general, with extensive military experience, committed to the Stoic philosophy of life.

Perhaps this was unintentional, but Crowe’s Maximus character seems like a hybrid of these two real-life Roman generals, Pompeianus and Claudius Maximus, combining some aspects of the former’s life with some of the character traits attributed by Marcus to the latter.

Stoicism in GladiatorThe original script for Gladiator reputedly wasn’t very good. In an interview, Russell Crowe said that among other changes he fought to have some philosophical themes from the Meditations incorporated.

I also remember talking about Marcus Aurelius and what a goldmine he would be in terms of thematics. And everybody else in the room, apart from Rid [Ridley Scott], was like, “What the fuck is he talking about?” They didn’t know that Marcus Aurelius was a philosopher. So I bought every one of ’em a copy of Meditations.

Crowe adds:

I still have a quote from it on the wall in my office: ‘Nothing happens to anybody which he is not fitted by nature to bear.’ Every piece of shit that was thrown at me, every challenge on that set, I would refer myself to that quote [laughs]. — Russell Crowe, Empire, June 2020

There are references in Gladiator to Marcus Aurelius being a philosopher.

My father spent all his time at study, reading books, learning his philosophy. — Commodus, Gladiator

Stoicism, unfortunately, is never mentioned by name. Nevertheless, at one point Maximus does recite the “Nothing happens to anybody…” quote above, from the Meditations (5.18). We can probably discern three additional references to Stoic philosophy in the script. The first is a sort of negative allusion, where Commodus is talking about the virtues he lacks:

You wrote to me once, listing the four chief virtues — wisdom, justice, fortitude, and temperance. As I read the list I knew I had none of them. But I have other virtues, Father... But none of my virtues were on your list. Even then it was as if you didn’t want me for your son. — Commodus, Gladiator

Anyone familiar with Greek philosophy will recognize these as the four “cardinal virtues” associated with the Socratic tradition, especially Stoicism. Notice that Commodus says that Marcus wrote to him of these virtues, which he actually wrote of many times in the Meditations.

In a 2003 article about Gladiator and Stoicism, the philosopher John Sellars has argued that the most Stoic character in the film is actually Proximo, portrayed by the late Oliver Reed. While training his gladiators, Proximo says:

Ultimately, we’re all dead men, sadly we cannot choose how, but we can decide how we meet that end in order that we are remembered as men. — Proximo, Gladiator

Apart perhaps from the concern with how they are remembered, this sounds very much like typical Stoicism. We should accept our own death as natural and inevitable, placing more importance on how we choose to meet it than upon the event befalling us itself.

Proximo also says to Maximus:

Marcus Aurelius is dead. We mortals are but shadows and dust, shadows and dust, Maximus. — Proximo, Gladiator

Proximo later repeats the phrase “shadows and dust” to himself as he meets his own demise, being encircled and executed by Commodus’ guards. It might remind us of passages such as the following:

Let your thoughts constantly dwell on those who have been greatly aggrieved at something that came to pass, and those who have achieved the heights of fame, or affliction, or enmity, or any other kind of fortune; and then ask yourself, ‘What has become of all that?’ Smoke and ashes and merely a tale, or not even so much as a tale. — Meditations, 12.27

Shadows and dust; smoke and ashes… Finally, toward the end of the movie, Maximus laughs as he says to Commodus:

I knew a man once who said, death smiles at us all. All that man can do is smile back. — Maximus, Gladiator

Commodus sneers “I wonder. Did your friend smile at his own death?”, to which Maximus replies “You must know. He was your father”, thereby attributing the saying to Marcus Aurelius. There are no direct quotations from the Meditations in Gladiator but some commentators have seen this line as resembling a loose paraphrase of the book’s final sentence:

So make your departure with a good grace, as he who is releasing you shows a good grace. — Meditations, 12.36

It’s also been compared to a passage near the start of the book, which concludes:

[Seek to die not] with complaints on your lips, but with a truly cheerful mind and grateful to the gods with all your heart. — Meditations, 2.3

In any case, although phrased somewhat differently it’s fair to say that Maximus’ line in the movie about smiling back at death captures a typical idea from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius.

Marcus and Stoicism in Gladiator IIWe know very little as yet about the sequel to Gladiator. However, I’m hopeful that we may see a few more traces of Stoicism in the movie for the following reasons. First of all, it would seem natural for the character of Lucius to make allusions to his deified grandfather, the emperor Marcus Aurelius, much as the characters of Maximus and Proximo did in the original film.

At the end of Gladiator, both Commodus and Maximus are dead. Lucius Verus, Marcus’ son-in-law, adoptive brother, and the father of the boy Lucius Verus II had already passed away before the start of the movie. So it’s not clear where that left things regarding the succession. Perhaps the boy Lucius was perceived as the rightful heir to the throne, although during this period, at roughly twelve, he’d probably have been considered too young to actually assume the position of emperor. Presumably, therefore, someone stepped in and seized power — that would seem the most likely scenario to me. It would make sense dramatically because it would leave Lucius disenfranchised from the imperial succession, most certainly placing his life in danger because he’d be perceived as having a rival claim to the throne. He’d probably have been forced into exile, if that’s the case.

Lucius’ mother Lucilla, the daughter of Marcus Aurelius, appears to be a prominent character in this movie, played once again by Connie Nielsen. She was still alive at the end of Gladiator and by the time the sequel is set, she will be aged roughly 55–60. It wouldn’t be surprising if she mentioned her famous father, especially as the events surrounding his death presumably set the stage, in part, for this episode in the story. So I am hopeful that Marcus Aurelius will at least get a mention in the new movie and if they’re going to do that, as in Gladiator, it’s arguably a good opportunity to throw in some more hints of the philosophy for which he was famous.

I’m eager to see Gladiator 2 when it’s released because I’m very interested in this part of history. Although it only really hinted at ideas from Stoic philosophy, I know the first Gladiator movie did encourage a great many people to learn more about Marcus Aurelius and the Meditations. So I hope the sequel might also have a similar effect.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 27, 2024

Enroll for Stoic Week 2024

This is your last chance to enroll for this year’s Stoic Week event — the annual online course run by the Modern Stoicism nonprofit organization.

Stoic Week is a free course, which roughly 20,000 people have completed since it was first created in 2012. I was one of the original designers, although many people have contributed over the years, including some leading academic experts on Stoicism.

Tim LeBon, the research director of Modern Stoicism, publishes a report each year on the psychological data collected from participants in Stoic Week.

Many have reported feeling calmer, more accepting of challenges, and better able to manage personal difficulties.

Having a clear list of daily exercises has helped some make Stoic practices a daily habit.

Engaging in Stoicism has led to happiness, improved perspective on life, and readiness for future challenges.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 24, 2024

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) and Stoicism

In this episode, I speak with Dr. Walter Matweychuk. Dr. Matweychuk is a practicing psychologist in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania Health System, and has an independent telehealth practice in Manhattan with clients worldwide. He is also an adjunct professor of Applied Psychology at New York University. He has personally worked with both of the two main pioneers of cognitive-behavioral therapy: Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck. He is the author of several books on Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT), including Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy: A Newcomer's Guide and The REBT Pocket Companion for Clients.

Every Saturday at 9 AM in New York City on Zoom, he does a demonstration of REBT with a volunteer willing to discuss a real problem, which has now surpassed 218 consecutive weeks; go to his website REBTDoctor.com to register for the link.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhat is Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy?

Why he chose to focus on REBT rather than Beck’s cognitive therapy

Mindfulness and acceptance based approaches in relation to REBT

What’s the future of REBT?

The key similarities are between Stoicism and REBT

The REBT model of anger

What would a philosophy of life based on REBT look like?

Links

LinksThe REBT Pocket Companion for Clients

Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy: A Newcomer's Guide

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.