Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 15

September 7, 2024

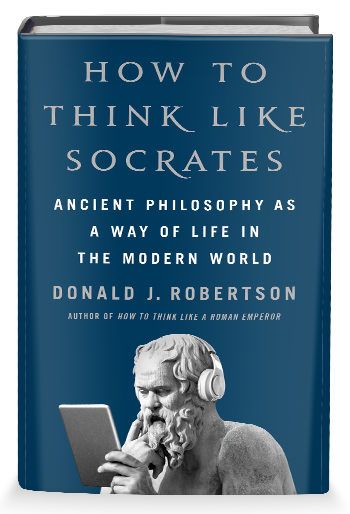

Bulk Orders of "How to Think Like Socrates"

People have been asking me how they can order multiple copies of my forthcoming book, How to Think Like Socrates. For instance, some of you who run companies doing coaching or training have asked about ordering 100 copies for clients. I just wanted to let everyone know there’s a way to save money when ordering in bulk. If you want to order copies now, it also helps us a lot because advance sales really boost the book’s chances of reaching a wider audience.

There’s a US based company called Porchlight, who specialize in offering substantial discounts for bulk orders, including forthcoming releases. They can ship internationally. Porchlight is offering, depending on the quantity of your order, discounts of up to 37% off the list price.

Order my other titles in bulk

Order my other titles in bulkYou can also bulk order the following titles from Porchlight at a discount.

How to Think Like a Roman Emperor (Harback)

How to Think Like a Roman Emperor (Paperback)

Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor (Hardback)

Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor (Paperback)

Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 5, 2024

Every omen is favourable to the wise. . .

CommentaryWhen a raven croaks inauspiciously, let not the external impression carry you away, but straightway draw a distinction in your own mind, and say, “None of these portents are for me, but either for my paltry body, or my paltry estate, or my paltry opinion, or my children, or my wife. But for me every portent is favourable, if I so wish; for whatever be the outcome, it is within my power to derive benefit from it.”

When you hear bad news do not allow yourself to be swept away by your initial impression of alarm but rather pause and take a step back from your thoughts and feelings. Immediately make a distinction between the events that befall you and your responses to them.

September 4, 2024

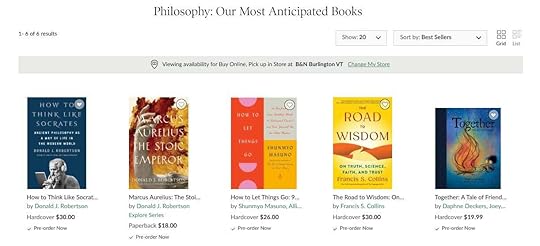

Quick: Get 25% off How to Think Like Socrates

I’m pleased to see that people are enjoying my latest book, How to Think Like Socrates. Barnes and Noble, who are offering a special discount for the next couple of days, have already listed it as a Bookseller’s Favourite, and one of the their Most Anticipated Philosophy Books of the year. Thanks everyone for subscribing to my newsletter and supporting the launch of this book. If you pre-order your copy it helps me a lot because the booksellers are then more likely to promote it to a wider audience. Please share this post with your friends, to help spread the word. Don’t miss the coupon code that I’ve included below for the special 25% discount!

Thank you to everyone who has been posting advance reviews on Goodreads, where it currently has 4.21 stars. The latest reviewer has written:

The author narrates the life and thought of Socrates in a way that transports you back in time and allows you to walk in the shoes of philosophy’s most important thinker. — Ryan Boissonneault

You can get How to Think Like Socrates from any bookstore. It’s available in hardback, ebook, and audiobook format. I’ll be recording the audio next week at a studio in Montreal — I’m currently rehearsing 254 Greek names and phrases!

Special Offer

Special OfferPreorder HOW TO THINK LIKE SOCRATES in any format at Barnes & Noble between now and 6th Sep to get 25% off with code PREORDER25. Note: this discount is only available to B&N members but free memberships are available — just sign up for B&N Rewards. Already a member? Order your copy at:

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 3, 2024

How would Socrates deal with anger?

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates says that when a good man knows that he is in the wrong, and being punished justly, his spirit will not feel anger. On the other hand, when a man believes that he has been wronged, and that he is a victim of injustice, his spirit will “seethe and grow fierce.”

He will seek justice, says Socrates, and his anger, and desire for revenge, “will not let go until either it achieves its purpose, or death ends all, or else, as a dog is called back by a shepherd, it is called back by the reason within and calmed.” You believe that someone has done something they should not have done, something unacceptable or unfair. You may even feel that they deserve to be punished. Anger, in other words, has long been associated with the belief that one has been wronged by another who has acted unjustly.

I’ve often asked myself whether Socrates’ philosophical arguments concerning “justice” could inform cognitive therapy for anger.

We don’t normally think of the philosophy of justice as being a branch of psychotherapy. Our conception of injustice, however, may affect our emotional resilience. Over a century ago, Sigmund Freud observed that “Melancholics always seem as though they had been slighted or treated with great injustice.” Recent research has indeed found evidence that “perceived injustice” is linked with and may be one of the causes of clinical depression.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

[This article is based on an excerpt from my latest book, How to Think Like Socrates, which is now available for preorder, in harback, ebook, and audiobook formats.]

Although cognitive therapy, one of the leading treatments for clinical depression, employs a technique called “Socratic Questioning”, which is loosely based on the Socratic Method, it seldom draws upon the philosophical insights found in the Socratic dialogues. However, I’ve often asked myself whether Socrates’ philosophical arguments concerning “justice” could inform cognitive therapy for anger. There’s one philosophical idea about justice in particular, of fundamental importance to Socrates, which I believe may hold great promise when combined with cognitive therapy for anger.

In the field of cognitive therapy, it has been proposed that anger is typically based on a belief that some rule has been broken or someone has acted unjustly. This is usually associated with an initial sense of emotional pain, or sadness, based on the perception that one or something one cares about has already been harmed or a sense of fear based on the perceived threat of harm. That pain or anxiety is quickly replaced with thoughts of retaliation or revenge, such as punishing the other person, when anger arises. Indeed, often anger can be interpreted as an attempt to cope with underlying anxiety by using another emotion to mask it.

Socrates couldn’t be more emphatic, in Plato’s Gorgias and elsewhere, that committing an injustice is worse than suffering one. His interlocutor finds this absurd: he believes that suffering injustice at the hands of others is worse, and more shameful. We may therefore expect that he was more prone to anger than Socrates: he probably felt ashamed and outraged whenever he perceived others to be acting unjustly toward him. Therapists often encounter rigid beliefs about the injustice or unfairness of certain events when treating patients for anger. If you find yourself unable to get past something that has made you angry, there are a few approaches that may prove useful.

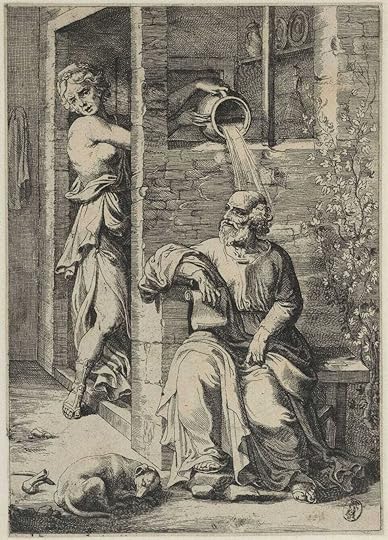

Socrates’ wife, Xanthippe, tips water over his headThe Consequences of Anger

Socrates’ wife, Xanthippe, tips water over his headThe Consequences of AngerOne of the first steps in tackling anger often consists in evaluating the consequences of the emotion itself, or associated rules and behaviors. First, you might want to ask yourself, generally, regarding your anger: How has that been working out for me? If you want to dig deeper, list the pros and cons, or costs and benefits of your anger. Think both in terms of the short-term and long-term consequences. It can be particularly helpful to compare the (perceived) short-term benefits of anger against its long-term costs.

Let’s say you are angry at a friend for not returning a phone call. What are the benefits of getting angry with the person? Perhaps there are none in the long term. Maybe in the short term you feel as though you’re temporarily getting something off your chest by expressing (“venting”) your anger. Maybe you feel that your anger might motivate you to do something constructive, like confronting the friend about how upset you believe he or she has made you feel. Are these real benefits? Answering the next question may help you decide: What are the costs of anger? Well, in the short term, although you may enjoy being angry in some ways, it probably also feels unpleasant and distressing in other ways. Longer term, though, it might affect different areas of your life such as your work, your relationships, and your personality in general, maybe also your physical health. In relation to the perceived benefits, are there hidden costs? Although venting can bring some relief in the heat of the moment, in the long run, it might just encourage you to become angrier and angrier, and to alienate some of your friends. Anger spreads: those who are angry with their enemies end up also being angry toward others. Usually this is obvious to everyone except the person who is angry— it’s a common blindspot. Perhaps being motivated by anger, likewise, can seem like a good idea at first, but eventually it may lead you to be forceful and act while your judgment is clouded by strong feelings— and that can lead to disaster!

In a sense, cost-benefit analysis in cognitive therapy can be understood in terms of the basic principles of behaviour therapy. Suppose we get much clearer about the disadvantages of some behaviour, perhaps expand our list of reasons against it, and maybe make them more vivid by focusing on them for longer and even visualizing them. Doing so potentially diminishes the habitual nature of the behaviour in question by associating it more powerfully in our minds with its perceived negative consequences. We’re making it easier to recall our reasons for wanting to stop doing the behaviour, which inevitably weakens our motivation to indulge in it again.

Contrasting ConsequencesI have found that a simple visualization technique, which I call The Choice of Hercules, or Fork in the Road, can be used to enhance the effect of negative consequences on motivation.

By visualizing the consequences of our actions rather than just thinking about them verbally, they have a more powerful effect upon our emotions

Focusing on the longer-term tends to enhance the effect, as the consequences of our actions tend to increase over time

Comparing the consequences of anger with those of having overcome your anger, can also enhance the effect on our motivation through contrast

I therefore suggest closing your eyes and imagining that you stand at a fork in the road, symbolizing your future. On the left, imagine carrying on with the status quo, by which I mean continuing to allow your anger to have control over you. See yourself from the outside, as if you’re an invisible observer. Picture how that would affect your personality, your relationships, and your overall quality of life, tomorrow, next week, next year, and even decades from now. Take time to picture this as clearly as you can, and allow yourself to respond emotionally to what you imagine.

Next, imagine on the right, your future without anger. That may simply mean that you do nothing when provoked, or just walk away, or take a time-out from the situation, or that you’re assertive or exercise moderation in your response. However you do it, just imagine that you’re no longer angry. Again picture how that would affect your personality, relationships, and overall quality of life, tomorrow, next week, next year, and decades from now. Spend some time comparing the long-term consequences of giving in to anger to those of having conquered anger, in this way. Your goal is to make these images so familiar that you can easily recall them whenever you begin to feel angry, or even notice early-warning signs of anger beginning to develop.

Socrates and the Paradox of AngerSocrates’ paradoxical claim that acting with injustice does us more harm than being the victim of injustice goes even further. The very emotion of anger is seen as harmful, not just in terms of its consequences, but by its very nature. Moreover, that perceived harm is psychologically amplified through contrast. Our anger is inherently worse for us than the anger of others, because it harms our very character whereas they can only harm our possessions or reputation, and so on. Our own anger reaches much deeper into the core of our being with its poison than another person, seeking to harm us, could ever reach.

What Socrates says here anticipates a slogan that we find recurring in the late Stoic writings, applied to other unhealthy passions. However, Marcus Aurelius applies it specifically to anger, when he writes that our own anger does us more harm than the person with whom we’re angry. If we could hold that philosophy of anger in mind, it would go beyond what cognitive therapy normally attempts, through cost-benefit analysis. It would radically undermine our motivation to engage in anger.

In cognitive therapy, we typically review situations where anger was triggered, and analyse our response. We could phrase this philosophical slogan in those terms by asking: which does us more harm, the trigger event or the anger we feel in response to it? The answer becomes clearer if we remind ourselves that we could potentially choose to look at the trigger event from a number of different perspectives, and we could also cope with it in a variety of different ways. So with that in mind, which does us more harm: the event or our anger about it?

During anger episodes, our focus of attention shifts dramatically, from our feelings of hurt, which are inside, toward the person we blame, who is outside. As soon as we ask this question, though, it forces us to return our attention to the anger within us. In other words, the question itself is perhaps inherently antagonistic to the mental state we call anger. It becomes difficult to remain angry as long as we can hold this question in mind.

In times of peace, prepare for war, as the saying goes. You should practice asking yourself this question when you’re no longer angry — when you’re feeling calm. That way, when you do become angry again, you will be prepared to recall the question, and return your attention to your inner state. Does your anger do you more harm than the things about which you’re angry? Does your anger do you more harm, for instance, than the perceived injustice of others ever could? It may be that you’re able to answer this question but, in fact, the very effort involved in asking it will often suffice to defuse your anger.

Avoiding AvoidanceI think it’s important to add that there are some issues that need to be addressed with this approach. A number of research studies have found evidence that belief that anger is dangerous and attempts to suppress feelings of anger can lead to various problems psychologically and even in terms of physical health. On the other hand, there’s evidence from several other studies that belief that anger is justified or helpful tends to cause other problems, such as relationship conflict or increased frequency of anger episodes, and so on.

I believe the solution to this paradox is quite simple, and familiar from dealing with anxiety, depression, and other psychological problems. The majority of people do not distinguish clearly between automatic and voluntary thoughts or, indeed, in terms of psychological activity in general. Few people make a clear distinction between the automatic thoughts, which usually happen first in an episode of anger, and the voluntary angry thinking that tends to follow.

Trying to suppress automatic thoughts is a fool’s errand, and tends to cause a number of problems. It’s better to accept our automatic thoughts, the ones that just pop unbidden into our mind, with indifference, and detachment. Voluntary thinking does not need to be suppressed, on the other hand, because it’s voluntary, we can just choose not engage in it or to think differently instead. In that sense, I think it’s possible to believe that our anger harms us more than the things that trigger it, while accepting the initial automatic thoughts of anger, as neither good nor bad, but withholding our voluntary assent to those thoughts, and doing nothing much in response to them, except perhaps viewing them with detachment. That allows us to view anger as harmful, which of course it is, without running into the psychological problems of thought (or feeling) suppression. Responding, in other words, with acceptance rather than avoidance or, if you like, avoiding avoidance of our automatic thoughts. This distinction isn’t always clearly articulated in ancient philosophy but from a modern psychological perspective we know that it’s important.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

This article is based on an excerpt from the more detailed discussion of anger to be found in my latest book, How to Think Like Socrates.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 25, 2024

Why You Need to Read Modern Books on Stoicism

I often see people online saying that there’s no point reading any modern books about Stoicism. You should just read the classics, they say, and ignore everything else.

I write books about and run courses on Stoic philosophy. I also run a large discussion group for Stoic philosophy on Facebook. One of the most common things we encounter online is the phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias whereby people who lack competence in some field will tend to underestimate their own incompetence. Professor Dunning, for instance, said that the Dunning-Kruger effect “suggests that poor performers are not in a position to recognize the shortcomings in their performance.”

Socrates introduced a similar idea, over two thousand four hundred years ago, called “double ignorance”. He describes it as a form of arrogance in which not only do we lack knowledge about some subject but we believe ourselves to know what, in fact, we do not know. We are ignorant of our ignorance. The Socratic Method was designed to combat this problem. Socrates saw this type of ignorance and intellectual conceit as one of the biggest threats that we face in life.

Nowadays, surprisingly, you’ll find people claiming to be experts who haven’t even read those books and whose only exposure to the subject is from a few blog articles, podcasts, or videos.

Increasingly, we encounter people online who have read very little on a subject assuming that they know everything there is to know. They don’t know how much they don’t know, precisely because they don’t know enough to realize how much there is to know. When it comes to Stoicism, that used to take the form of people who have read one or two of the most popular classics— usually the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius or Handbook of Epictetus — assuming that they’re experts and have nothing left to learn about the philosophy. Nowadays, surprisingly, you’ll find people claiming to be experts who haven’t even read those books and whose only exposure to the subject is from a few blog articles, podcasts, or videos. I’ve even met “Stoicism” coaches, podcasters, and even authors, who have never read any books on the subject. (Some people just don’t like reading books, which is fair enough, but it can become problematic for their students if they decide, nevertheless, to offer courses and workshops on subjects they’ve never read about or studied themselves.)

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Now, it’s true that the ancient Stoics thought that too much study was potentially a vice, if it didn’t actually improve our character. Knowledge for its own sake isn’t a virtue in Stoicism. Scholars who argue over how many angels can dance on the head of a pin are simply wasting their time. Stoicism isn’t about reading endless books. However, neither is it about intellectual laziness. You can’t make a virtue out of ignorance when it comes to the most important things in life. Marcus Aurelius, for instance, although he tells himself to put his books away, was a voracious reader.

Throw away your books; no longer distract yourself: it is not allowed. — Meditations, 2.2

But cast away your thirst for books, so that you may not die murmuring, but cheerfully, truly, and from your heart thankful to the gods. — Meditations, 2.3

He meant that he should cease wasting his time on irrelevant studies, stop arguing about what a good man should be, and just be one. That’s typical Stoicism. He didn’t mean that people should embrace ignorance, though, and rest on their laurels after only having scratched the surface of the subject.

None of these books from the founders of Stoicism actually survive today.

None of these books from the founders of Stoicism actually survive today.The central principles of Stoicism are actually quite simple, as Epictetus says. For example, “to make correct use of our impressions”. But if people don’t understand what that means, as he also says, the explanation takes time and can become lengthy. When it comes to reading the Stoics there’s a lot that people can gain from further study, particularly reading modern texts. I’m not suggesting that people have to read my books. I’d be happy if they read more or less any modern commentaries, as long as they were trying to genuinely penetrate deeper into the real meaning and practical application of the ancient texts.

For example, I know that I would only have obtained half as much value from reading the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius if I hadn’t also read books like Pierre Hadot’s The Inner Citadel, which explain the philosophical presuppositions of Marcus’ Stoic philosophy, the historical context that give his remarks meaning, and the connotation of the Greek words and phrases he was using. People study the Meditations for decades. There are many different translations you can compare. You can study the original Greek, learn about the philosophical and historical context, and read the surviving Roman histories of Marcus’ rule, in order to learn more about his character and some of the people to whom he’s referring in the text, such as his main philosophical tutor Junius Rusticus.

In fact, I’d go as far as to say that it’s virtually impossible to fully understand texts like the Meditations and the Handbook of Epictetus unless you have at least a basic grasp of the principles of Stoic philosophy. None of the main surviving Stoic texts — containing the thought of Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius — were intended as systematic treatises on Stoic philosophy. They all take for granted that the reader will have some familiarity with the philosophy to which they’re referring, as well as to the historical events and other individuals mentioned.

The closest thing we have to a systematic presentation of Stoicism in an ancient text is the third chapter of Cicero’s De Finibus, in which Cato of Utica is portrayed discoursing at length on Stoic Ethics. However, that’s pretty limited in scope. The only way to really get a primer in Stoic philosophy is to read modern commentaries, such as Brad Inwood’s excellent Stoicism: A Very Short Introduction, John Sellars’ Lessons in Stoicism, or other books which are available to guide you. That way you’ll be more able to understand what Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius take for granted, and won’t run the risk of misinterpreting their philosophy.

And I don’t just mean at what some people like to call the “theoretical” level but in your daily practice of Stoicism. Individuals who haven’t properly acquainted themselves with the philosophy often get completely the wrong idea about what the Stoics are actually suggesting you do. They also don’t realize how many practical techniques the Stoics describe. In my first book on Stoicism, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, I tried to give a comprehensive overview of the parallels between ancient Stoicism and modern evidence-based psychotherapy. I listed roughly eighteen distinct psychological strategies that can be found in the Stoic writings. Yet people who think they’ve exhausted everything the ancient texts have to teach them and have nothing more to learn can usually only describe one or two of those strategies, if you’re lucky. There’s a lot more to learn, in other words, not only about the theory that informs the practice but also about the practice itself.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 20, 2024

Was Aristo an Agnostic Stoic?

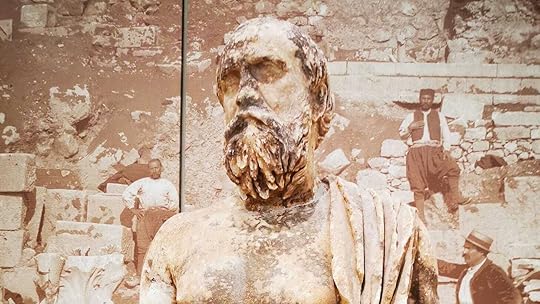

Statue of unknown Greek philosopher, from Delphi Museum

Statue of unknown Greek philosopher, from Delphi MuseumIt’s sometimes asserted that all ancient Stoics believed in Providence, and that this belief is necessary to justify the rest of their system of philosophy, especially their ethics. In fact, there’s no more reason for modern thinkers to conclude that belief in Providence is a necessary premise for Stoic Ethics than it is for more or less any other ethical system.

Their precursors, the Cynics, for instance, held similar ethical views to the Stoics but they did not typically study theology or attempt to justify their ethic by appeal to belief in Providence. Cicero, an Academic, broadly agreed with Stoic Ethics, but grounded his virtue ethic in human nature and reason rather than dogmatic belief in Providence. Today, some people, usually Christians or followers of other faiths, are convinced that you cannot have ethics without belief in God — they often say it’s simply inconceivable to them. Others, mostly agnostics or atheists, feel that you can derive ethical conclusions from principles based on human nature and reason, without any reference to God. In the ancient world, philosophical discussion about the existence of God (or the gods), and its ethical implications, was not at all unusual, although belief in the established pantheons of gods, and respect for the traditional religious customs of Greece and Rome was, typically, the norm.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

As for what the ancient Stoics believed, given that so few of their original writings survive today, it seems impossible for us to make any meaningful generalizations in this regard. How could anyone claim to know what 100% of ancient Stoics believed about the gods based on less than 1% of their writings? The most we could reasonably assert is Zeno and some of his best-known followers, throughout the five centuries or so during which the school flourished, all shared a broadly similar belief in Providence, although we also have evidence of many theological disagreements between leading Stoic thinkers.

Aristo was one of Zeno’s most highly-regarded students, and although none of his writings survive, his influence endured for centuries.

By agnostic, I mean, in the broad sense, “a person who is unwilling to commit to an opinion about something”, and more specifically, in the more narrow sense, “a person who believes that God is unknowable or one who is unwilling to commit to any opinion about the nature of God, or about God’s existence or nonexistence.” An atheist, by contrast, is someone who claims to know that God does not exist. We have no evidence that any ancient Stoics were atheists. There was, however, one Stoic philosopher, very well-known in antiquity, who appears to have adopted an agnostic position regarding the nature, and perhaps even the existence, of the gods.

Aristo of Chios was a student of Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, and therefore a fellow-student and subsequently a rival of Cleanthes, who succeeded Zeno as head of the school. His name is spelled Ariston in ancient Greek, but the final n is, by convention, usually dropped in English, although you will find it spelled both ways by different authors — the Greek name Platon is likewise more familiar to us as Plato. (I have amended several of the texts below for consistency in this regard.) Aristo was one of Zeno’s most highly-regarded students, and although none of his writings survive, his influence endured for centuries. We find references to his teachings in the writings of Cicero, Seneca, and Plutarch, among others, and an entire chapter of Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is dedicated to his life and thought.

Surprisingly, one of the main controversies about Aristo is whether, in fact, he was a Stoic. He was certainly a student of Zeno’s, but came to disagree quite markedly with some of his teacher’s views. It’s unclear, though, to what extent this disagreement was perceived by them as marking an actual break from Stoicism. Diogenes Laertius has some nuanced things to say about Aristo’s relationship with other Stoics. However, he does label Aristo as a Stoic, albeit an unorthodox one.

It seems to me that Aristo’s break from Zeno was partial enough that later generations of philosophers appear to disagree as to whether he should be classed as an unorthodox Stoic or the founder of a distinct, but minor, school of his own. Cicero, for instance, sometimes contrasts the views of Aristo with those of the Stoics, which can be read as implying that he thinks of them as representing two different schools of philosophy. Our clearest evidence, however, comes from Seneca, himself a Stoic, who unequivocally considers Aristo to be a fellow Stoic. As we shall see, Seneca, and at least one other ancient author, referred to him as Ariston Stoicus or “Aristo the Stoic”.

In this article, I’ll look in depth at the evidence in relation to two questions:

Was Aristo a Stoic?

Did he reject the orthodox Stoic belief in a Provident God?

Marcus Aurelius on “Aristo”Before I do so, however, it’s worth drawing attention to a famous passage from the private letters of Marcus Aurelius to his rhetoric tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto. Here the young Marcus, as Caesar, mentions the striking impact upon him of having read an author called Aristo.

Aristo’s books just now treat me well and at the same time make me feel ill. When they teach me a better way, then, I need not say, they treat me well; but when they shew me how far short my character comes of this better way, time and time again does your pupil blush and is angry with himself, for that, twenty-five years old as I am, no draught has my soul yet drunk of noble doctrines and purer principles. Therefore I do penance, am wroth with myself, am sad, compare myself with others, starve myself. A prey to these thoughts at this time, I have put off each day till the morrow the duty of writing. But now I will think out something, and as a certain Athenian orator once warned an assembly of his countrymen, that the laws must sometimes be allowed to sleep, I will make my peace with Aristo’s works and allow them to lie still awhile, and after reading some of Tully’s [i.e., Cicero’s] minor speeches I will devote myself entirely to your stage poet. However, I can only write on one side or the other, for as to my defending both sides of the question, Aristo will, I am sure, never sleep so soundly as to allow me to do that! — Marcus Aurelius to Fronto

Aristo was a fairly common Greek name, e.g., it is believed to have been the name of Plato’s father, and of at least one other famous philosopher, an Aristotelian called Aristo of Ceos, and a prominent Roman jurist called Titius Aristo. Scholars therefore disagree as to whether Marcus is referring to our Aristo or not in this letter. However, on reflection, for the reasons below, it seems probable to me that he was, indeed, talking about Aristo of Chios.

By this time in his life, aged twenty-five, Marcus Aurelius is already perceived by Fronto as a Stoic, although Marcus did read widely, and studied other schools of philosophy. Aristo of Chios was an important figure in the history of Stoicism, and one known for his brash and challenging nature.

When [Zeno’s] pupil Aristo discoursed at length in an uninspired manner, sometimes in a headstrong and over-confident way. "Your father," said he, "must have been drunk when he begat you." Hence he would call him a chatterbox, being himself concise in speech. — Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laertius also claims Aristo was nicknamed the Siren, presumably because of his captivating eloquence, and he remarks on Aristo’s uniquely persuasive and influential manner of speaking. Several books are attributed to him including a four-volume collection of his letters to Cleanthes, and many works the authenticity of which was in doubt, including a volume titled On Zeno's Doctrines and two volumes of Exhortations to philosophy. If Marcus was this shaken by whatever he read it seems most likely to have come from the “Aristo” most famous for possessing the ability to affect people in such a powerful way with his words. Marcus certainly resembles a man who has been filled with anguish, having heard the song of a Siren — the nickname we’re told Aristo of Chios had earned.

We can, moreover, find several parallels between the ideas for which Aristo was famous and certain themes in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. As we shall see, for instance, Aristo questioned the value of studying Logic and Physics. Marcus refers several times to concerns he has about having spent too much time on these subjects and not enough on Ethics. Aristo expresses agnosticism about the nature of God; Marcus Aurelius, about nine times, expresses a sort of methodological agnosticism, asserting that whether the universe is produced by God or atoms, i.e., Providence or randomness, either way, Stoic ethical principles are still valid. Marcus also seems to have been drawn to Cynicism earlier in his life, a tradition with which Aristo appears to have associated himself.

Although we cannot be certain, it seems plausible and indeed likely to me that Marcus was describing the powerful impact upon him of reading some books by Aristo of Chios, perhaps shared with him by his mentor, Junius Rusticus, or another Stoic teacher.

Aristo’s StoicismDiogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is our most important source for information on Aristo. In the introductory chapter, Diogenes reviews the different sects of philosophy, and different ways of classifying them. Although he mentions Aristo of Chios here, Diogenes does not list him or his followers as constituting a distinct philosophical sect or school. Presumably, therefore, he must be lumping them in with the other Stoics in this part of the book.

Indeed, Lives and Opinions contains a whole section dedicated to the Stoics, which consists of seven chapters, each of which deals with the life and thought of a different member of their school. The preceding section, on the Cynics, concludes with the words:

So much, then, for the Cynics. We must now pass on to the Stoics, whose founder was Zeno, a disciple of Crates [of Thebes, the Cynic]. — Diogenes Laertius

The first chapter, of course, is about Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school. It is, by far, the longest chapter in this section because it includes a detailed summary of the doctrines of the Stoic school. However, it ends with the words “But the points on which some of them [i.e., some of the Stoics] differed are as follows." The following chapters therefore describe ways in which other Stoics departed from the original teachings of Zeno, and the first of those is the chapter concerning Aristo of Chios.

We’re told that Aristo began lecturing in the Cynosarges, although it’s not clear whether he did this while Zeno was still alive. After Zeno’s death, Cleanthes, author of the Hymn to Zeus, succeeded him as head of the Stoic school, and placed greater emphasis on worship of the gods. It’s therefore possible that when Cleanthes took over teaching at the Stoa, Aristo set up a rival branch of Stoicism at the Cynosarges, which, in contrast to the more theological teachings of Cleanthes, espoused a position closer to Cynicism, in which the study of Logic and Physics (including theology) are downplayed and Ethics takes centre stage.

Once Aristo became established as a teacher in his own right, he earned the reputation of being a αἱρετιστὴς (hairetistes), which literally means “one who chooses”, i.e., he choose a different approach to Zeno — it’s the etymological root of our English word “heretic”. It can potentially mean someone who has founded a new sect of philosophy but could also simply mean that he disagreed with Zeno, while remaining part of the broad Stoic movement. There’s no explicit reference to him joining another school of philosophy, or decisively breaking away from the Stoic school and, as we’ve seen, he’s was still referred to both by Diogenes and later authors as a Stoic.

The Cynosarges was one of the three main gymnasia of ancient Athens, along with the Academy and Lyceum, where the schools of Plato and Aristotle were located respectively. The Cynosarges was particularly known for being less exclusive than the Lyceum and Academy, because it was open to poorer citizens, resident foreigners, known as metics, and illegitimate children, who often had one foreign parent. Whereas Zeno, and subsequently Cleanthes, only appear to have had a handful of students, Aristo attracted quite a large following:

Once when somebody reproached [Chrysippus] for not going with the multitude to hear Aristo, he rejoined, "If I had followed the multitude, I should not have studied philosophy."—Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes also described Aristo as being particularly “persuasive and influential with the crowd” or mob (ὄχλος), i.e., relatively large audiences, at the Cynosarges and perhaps elsewhere, including many poorer and less well-educated residents of Athens. That may help to explain Plutarch’s remark that “Aristo of Chios, when the sophists spoke ill of him for talking with all who wished it, said, ‘I wish even the beasts could understand words which incite to virtue’” (Plutarch, Table Talk, 10.1). In other words, Aristo took Stoicism from the Agora, in the centre of Athens, to the Cynosarges, outside the city walls, where he adopted a simpler, more austere, and populist approach, and drew large audiences including many foreigners and poorer citizens.

We’re told that one of Socrates’ most influential followers, Antisthenes, was looked down on by some Athenians because his mother was Thracian and therefore classed as a “barbarian”. Almost a century before Aristo, Antisthenes had taught his austere form of Socratic philosophy in the Cynosarges. Antisthenes was considered by some ancient authors to be the founder, or at least precursor, of the Cynic school, and his views may well have had some influence on Aristo. As we shall see, there are certainly good reasons to compare Aristo to the Cynics.

Diogenes Laertius claims that some referred to Aristo as an αἱρετιστής, which can mean the founder of a philosophical sect or school. He also tells us the names of two philosophers who were called “Aristonians” (Ἀριστώνειοι), because they claimed to be followers of Aristo. From this we can infer that Aristo was not the only one who held the key philosophical doctrines attributed to him. If he can be described as an agnostic Stoic, for instance, he was apparently not alone, as we’re told he had many followers. Indeed, Aristo appears to have attracted a larger audience at the time, and perhaps more followers, than Zeno or Cleanthes.

Some people have read that as meaning that Aristo could not have been a Stoic, based on the assumption that if a philosopher founded a sect or had students designated with his name in this way, they could no longer be considered members of broader school, such as Stoicism. However, that assumption is certainly false. It’s disproved by the the fact we know of others, including groups of Stoics, who were identified as members of a particular branch within a broader school of philosophy. Someone can, of course, be referred to both as a “Thomist” or an “Augustinian” and still be a “Christian”. We know that in the Roman Imperial period there were three branches of Stoicism whose followers were divided into disciples of the last three scholarchs of the Stoic school:

And there are many meetings of philosophers in the city, some called the pupils of Diogenes [of Babylon], and others, pupils of Antipater [of Tarsus], others again styled disciples of Panætius [of Rhodes]. — Athenaeus of Naucratis, Deipnosophists

They were all still Stoics, just followers of different branches of the philosophy. We may likewise conclude that Aristo’s followers could have been viewed as members of an Aristonian branch of Stoicism. This group of early Stoics could have been referred to, therefore, as Aristonians just as later Stoics were referred to as Diognitists, Antipatrists or Panaetians.

After concluding his discussion of Aristo, Herillus, and Dionysius, Diogenes writes:

These three, then, are the heterodox Stoics. The legitimate successor to Zeno, however, was Cleanthes: of whom we have now to speak.

Here the word used to refer to Aristo and the others is διενεχθείς, meaning simply “one who disagreed”, i.e., with Zeno’s original Stoicism, and presumably also with Cleanthes. It is usually translated as referring to “heterodox” Stoics. All three of these men disagreed with Zeno’s original teachings but we cannot conclude from that alone that they all broke away from the Stoic school. Indeed, of the three, Diogenes the Renegade, is the only one whom we’re told broke from the Stoic school, in his case to become a follower of the Cyrenaics instead.

Athenaeus of Naucratis, writing in the late 2nd or early 3rd century CE, explicitly refers to “Aristo of Chios, who was one of the sect of the Stoics”, in order to criticize him for allegedly sacrificing virtue for certain pleasures (Deipnosophists). By contrast, in the same passage, Athenaeus refers to Dionysius of Heraclea, who “apostatized from the doctrines of the Stoics, and passed over to the school of Epicurus”. In other words he explicitly states, like Diogenes Laertius, that Dionysius abandoned the Stoic school to join the Cyrenaic or perhaps Epicurean school of philosophy. Athenaeus would surely have likewise referred to Aristo having “apostatized”, or broken away, from the Stoic school, if he had actually done so, but instead he continues to refer to him here as a Stoic.

Diogenes Laertius refers to them collectively as the “heterodox Stoics”, whereas nobody refers to Aristotle and Zeno, for instance, as “heterodox Platonists”. This, and the fact that Diogenes includes chapters about them alongside the more orthodox Stoics, makes it clear that despite their disagreements with Zeno, they were still classified primarily as Stoics. It could, of course, be that some of these men considered themselves, or were considered by Zeno and his followers, as representing distinct schools of philosophy from Stoicism but nevertheless that later authors, such as Diogenes Laertius, lumped them together for convenience, because they had enough in common to justify doing so.

It’s worth noting that Aristo is never referred to as a Cynic, despite the obvious similarities between their doctrines and the fact he based himself at the Cynosarges. Why was he not simply classed as a Cynic, though? Perhaps because we don’t find any reference to him embracing the austere ascetic lifestyle for which Cynics were typically known. In fact, we’re told he was criticized by some for his love of pleasure and luxury. We’re told one of his students, called Eratosthenes the Cyrenean, wrote a book titled Aristo, in which he portrayed his master as having become, over time, addicted to luxury:

Ariston StoicusAnd before now, I have at times discovered him breaking down, as it were, the partition wall between pleasure and virtue, and appearing on the side of pleasure. — quoted in Athenaeus, Deipnosophists

However, Seneca, himself a Stoic, actually refers, unequivocally, as we shall see, to Aristo as a fellow Stoic. This suggests that it was not unusual for later philosophers to classify Aristo merely as an unorthodox Stoic, rather than someone who actually broke away decisively from the Stoic school, and this is probably also what Diogenes Laertius meant by referring to him as a “heterdox Stoic”.

Seneca, speaking of the division of philosophy concerned with “supplying precepts appropriate to the individual case”, such as practical advice about how to raise one’s children, writes:

But Aristo the Stoic, on the contrary, believes the above-mentioned department to be of slight import – he holds that it does not sink into the mind, having in it nothing but old wives’ precepts, and that the greatest benefit is derived from the actual dogmas of philosophy and from the definition of the Supreme Good. When a man has gained a complete understanding of this definition and has thoroughly learned it, he can frame for himself a precept directing what is to be done in a given case. — Seneca, Letters 94

In other words, if you really grasp that virtue is the only true good, then you don’t need philosophers to spell out in fine detail exactly how to raise your children, run your business, conduct yourself in public office, and so on. Aristo, again, is depicted as simplifying Stoicism, in order to focus on its basic ethical principles.

In the original Latin, Seneca calls him Ariston Stoicus, which literally means “Aristo the Stoic”. We also find this phrase used in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, by the Christian apologist Minucius Felix in Octavian, where he writes:

Xenophon, the disciple of Socrates, says that the true God’s form cannot be seen, and therefore should not be inquired into; Aristo the Stoic, that it is beyond all comprehension: both realizing that the majesty of God is the despair of understanding. — Minucius Felix, 19.12-3

We’ll return to Aristo’s claim that the nature of God is unknowable later. For now, the key part of this passage is that fact that Minucius Felix follows Seneca in referring to him unequivocally as Ariston Stoiconus or “Aristo the Stoic”. Neither Seneca nor Minucius Felix feel the need to qualify or explain this designation — they assume their readers will find it uncontroversial. It’s likely, based on the evidence from Seneca and this later Christian apologist, therefore, that Aristo, at least in the imperial period, was viewed unequivocally as a Stoic.

Aristo and the CynicsOne reason why Aristo may have been referred to as a Stoic, while disagreeing with Zeno, is that whereas others may have been drawn more in the direction of opposing philosophers such as Platonism or Cyrenaicism, Aristo appears to have been more inclined toward Cynicism. Zeno himself was originally a Cynic for many years, and the Stoics were often seen as closely-related to the Cynics. Aristo’s disagreement with Zeno may, therefore, have been perceived not as a break from the school but rather as a return to Stoicism’s Cynic roots. For instance, Diogenes Laertius concludes his discussion of the Cynic philosophers, including Antisthenes, by comparing their teachings, particularly their neglect of Logic and Physics in favour of Ethics, to the philosophy of Aristo of Chios.

Such are the lives of the several Cynics. But we will go on to append the doctrines which they held in common--if, that is, we decide that Cynicism is really a philosophy, and not, as some maintain, just a way of life. They are content then, like Aristo of Chios, to do away with the subjects of Logic and Physics and to devote their whole attention to Ethics. — Diogenes Laertius

As Physics includes theology, this means that the Cynics in general abandoned the study of theology, and that Aristo, the Stoic, came to resemble the Cynics in also abandoning the study of theology, in order to focus exclusively on ethics. This focus on ethics was also traditionally associated with Socrates. We’re told more about Ariston’s reasoning here in a fragment from Stobaeus:

Ariston said that of the things investigated by philosophers, some are up to us, some are not up to us, and some are beyond us. Ethics is up to us, dialectic is not up to us (for it does not contribute to the correction of life), and physics is beyond us, for it is impossible to know and is of no use. — Stobaeus, Eclogues II 8, 13 W

We’re likewise told that Aristo resembled the Cynics with regard to his central Ethical doctrines.

Whatever is intermediate between Virtue and Vice they [Antisthenes and the Cynics], in agreement with Aristo of Chios, account indifferent. — Diogenes Laertius

Seneca also portrays Aristo as someone who emphasized the worthless nature of external goods:

Then it will be in our power to understand how contemptible are the things we admire – like children who regard every toy as a thing of value, who cherish necklaces bought at the price of a mere penny as more dear than their parents or than their brothers. And what, then, as Aristo says, is the difference between ourselves and these children, except that we elders go crazy over paintings and sculpture, and that our folly costs us dearer? — Seneca, Letters 115

One way of viewing this is that Cynicism was originally viewed more as a philosophical way of life rather than a system of philosophical teachings. Diogenes Laertius implies that there was some difference of opinion as to whether “Cynicism is really a philosophy, and not, as some maintain, just a way of life”, for instance. Aristo, having been a student of Zeno, may have set up teaching a form of Stoicism in the Cynosarges, which more closely resembled Cynicism, in its simplicity, but was more than just a way of life, and went beyond Cynicism in presenting a systematic approach to ethics, based on philosophical arguments, which were indebted to Stoicism.

Aristo’s AgnosticismZeno’s Stoic philosophy consisted in a set of doctrines divided into three broad topics: Ethics, Physics, and Logic.

[Aristo] wished to discard both Logic and Physics, saying that Physics was beyond our reach and Logic did not concern us: all that did concern us was Ethics. — Diogenes Laertius

As we have seen, discarding Stoic Physics would mean, among other things, discarding Stoic theology. (I will set aside, for the purposes of this discussion, his reference to Logic.)

What we’re told here can be understood in relation to what Diogenes Laertius said, at the opening of his chapter on Aristo, about the goal of life being “perfect indifference to everything which is neither virtue nor vice.” Aristo must have viewed the study of theology as one of the things that are absolutely indifferent, being neither, in itself, a virtue nor a vice. We can imagine Aristo saying that studying Zeno’s theology, in itself, will not make you virtuous.

Living in accord with virtue and studying theology are not the same thing, and should not be equated. Indeed, either love or hatred of theology could be forms of vice, if they lead us to place too much value on something external to our own moral character. This reminds me of the Buddhist doctrine that the question as to whether or not the gods exist is “indifferent” — rather than answering the Buddha would simply raise one finger to signal to his followers that they were asking him the wrong sort of question.

Seneca also highlights the fact that Aristo abandoned Logic and theology as superfluous, adding that he viewed them, in some regard, as providing contradictory guidance in life.

Aristo of Chios remarked that the natural and the rational were not only superfluous, but were also contradictory. He even limited the “moral,” which was all that was left to him; for he abolished that heading which embraced advice, maintaining that it was the business of the pedagogue, and not of the philosopher – as if the wise man were anything else than the pedagogue of the human race! — Seneca, Letters 89

Cicero makes it clear that Aristo did suspend judgement and adopt a sort of agnosticism with regard to many questions about Physics, including what at the time appeared unfathomable mysteries of nature such as how large or small the sun was.

Socrates, then, is free from this ridicule, and so is Aristo of Chios, who thinks that none of these matters can be known. — Cicero, De Finibus, 2.39

Specifically with regard to theology, Cicero states in another text:

Aristo holds equally mistaken views. He thinks that the form of the deity cannot be comprehended, and he denies the gods sensation, and in fact is uncertain whether the god is a living being at all. — Cicero, De Natura Deorum, 1.14

(This key passage in Latin: Cuius discipuli Aristonis non minus magno in errore sententia est, qui neque formam dei intellegi posse censeat neque in deis sensum esse dicat, dubitetque omnino deus animans necne sit.)

Moreover, Aristo cannot believe that God is Provident because he denies that the gods have any sensation, his point perhaps being that as the gods lack physical eyes and ears they can neither see humans nor hear their prayers.

It’s difficult to read these words without being reminded of the notorious opening lines of Protagoras’ work On the Gods:

As to the gods, I have no means of knowing either that they exist or that they do not exist. For many are the obstacles that impede knowledge, both the obscurity of the question and the shortness of human life. — Protagoras, On the Gods

Aristo’s agnosticism about the nature of God clearly follows from his more general belief that the study of Physics, or the Nature of the universe, of which theology was deemed a part by the Stoics, is simply “beyond” mortal comprehension.

It may seems unclear whether Aristo meant that the existence of God (or the gods) is uncertain or merely that his Nature is completely unknowable, and therefore indifferent to us. A few lines earlier, however, Cicero had said that Zeno of Citium wanted to call the law of nature divine, to which he objects: “How he makes out this law to be alive passes our comprehension; yet we undoubtedly expect god to be a living being.” At least for Cicero, therefore, Aristo’s being uncertain whether or not God is a living being is tantamount to being uncertain whether or not he exists.

Indeed, if the nature of the gods is completely incomprehensible, it is difficult to imagine how anyone could know for certain that they exist. It appears to me, therefore, that Aristo in addition to being agnostic about the Nature of God was probably also agnostic about God’s existence. How can we claim to know that something exists if we know nothing whatsoever about its nature? The fact that Aristo abandoned theological studies as worthless appears to confirm that he believed theological questions were beyond human comprehension, which suggests he was more like a straightforward agnostic than a proponent of some subtle mystical theology.

ConclusionAristo is a fascinating but somewhat mysterious figure, in the history of philosophy. He was clearly an important follower of Zeno, who, perhaps after his teacher died and Cleanthes took over the Stoic school, set up in the Cynosarges teaching a hybrid of Stoicism and Cynicism to a larger and more mixed audience. He was known as a Siren, a powerful and compelling speaker, who converted many others to follow philosophy as a way of life.

Although Aristo certainly disagreed with Zeno, Cleanthes, and other early Stoics, and attracted his own group of followers, he was still referred to by the historian of philosophy, Diogenes Laertius, and by fellow-Stoic Seneca, among others, as a Stoic, albeit an unorthodox one. Diogenes Laertius calls him a “heterodox Stoic”. Seneca and the apologist Minucius Felix both refer to him unequivocally as Ariston Stoicus — “Aristo the Stoic”. It seems to me that he was probably widely regarded as a Stoic who, in key regards, sought to return to the Cynic roots of the philosophy.

Several ancient authors claim that Aristo and Cleanthes, though leading rival philosophical schools influenced by the Stoic teachings of Zeno, were actually on relatively friendly terms with one another.

But when the truth has appeared and shone forth in philosophy, all who have grasped the work enjoy it without bloodshed. For this reason, Aristo embraced Cleanthes and shared his students. — Themistius or. 21 p. 255

The fact that students were attending the lectures of both Aristo and Cleanthes at the same time lends weight to the notion that they probably saw themselves as part of a single Stoic tradition.

Aristo was certainly known for teaching that the study of theology was unnecessary, and for abandoning Physics and Logic to focus on Ethics. He seems to have felt that the value of Stoic theology was undermined by our inherent uncertainty regarding the Nature of God, which he concluded was incomprehensible to mortals. We’re not explicitly told that he was agnostic about the existence of God but this seems to follow naturally from his abandonment of theology and assertion that God’s nature is utterly unknowable. I believe Aristo is very likely, therefore, to have been agnostic about the existence of God. Moreover, he was far from being unique in that regard. We’re told he attracted larger audiences, and perhaps had more followers, than Zeno or Cleanthes. On that basis, it seems possible that, at one time, the majority of Stoics were actually agnostics who followed Aristo’s branch of the philosophy.

Aristo certainly thought that theological speculation was a distraction from the fundamental ethical questions in life. We just need to grasp that virtue is the only true good and live accordingly. We should be wary of overcomplicating ethics. When Marcus Aurelius says, for instance, that we should stop arguing about what a good man is and just be one (Meditations, 10.16), he sounds like he could be paraphrasing Aristo of Chios.

Moreover, we’re told that Aristo defined the telos or supreme goal of life as ἀδιαφορία or indifference (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 2.21). Although Marcus Aurelius frequently repeats the more orthodox Stoic doctrine that we must distinguish the relative value of indifferent things, nevertheless, at times he portrays the goal of life as a form of indifference, synonymous with virtue.

As to living in the best way, this power is in the soul, if it be indifferent to things which are indifferent. —Meditations, 11.16

Elsewhere, Marcus repeats this point:

Adorn yourself with simplicity and modesty, and with indifference towards the things which lie between virtue and vice. — Meditations, 7.31

His language in this passage (despite subtle differences in the original Greek) seems to me to echo Aristo’s definition of the supreme goal of life:

[Aristo] declared the goal [telos] to be a life of indifference towards the things which lie between virtue and vice. — Diogenes Laertius

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 19, 2024

Get my biography of Marcus Aurelius half price!

Apologies for plugging my latest book but, honestly, I just wanted to let all of you who subscribe to my newsletter know that, if you’re interested in Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, now is your perfect chance to grab a bargain. The hardback copy is available half price! Amazon and Barnes & Noble are both offering 50% off deals at the moment, in the US. If you check other booksellers, or other regions, you may also find they’re matching these special offers. (Also sending this email now, and not scheduling it, because these offers are time-limited.)

“Addictively written, this riveting visitation of the fascinating figure of Marcus Aurelius is as comprehensive as it gets, covering everything from his reign to his philosophy.”

— Bookseller Favorite, barnesandnoble.com

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What people are saying…“Given the erratic, not to say murderous, behavior of many of [Marcus’s] predecessors, . . . how did so sterling a character as Marcus come about? That is the subject of Donald J. Robertson’s excellent biographical study.”—Joseph Epstein, National Review

“Eminently readable. . . . A leading light in the modern revival of Stoic philosophy, Robertson directly and elegantly draws out the connections between Marcus’ experiences in the unforgiving crucible of Roman imperial politics and the philosophical ideas he expresses in the Meditations. . . . An invaluable companion to the Meditations itself.”—Peter Juul, Liberal Patriot

“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“[Robertson] thoughtfully and readably capture[s] the essence of this great man and his great life. It’s a must read for any aspiring Stoic.”—Ryan Holiday, coauthor of #1 New York Times bestseller The Daily Stoic

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and Its Modern Significance

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of The Pocket Stoic

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 16, 2024

Quick Survey: Ancient Wisdom Retreat in Greece?

Have you ever dreamt of visiting the birthplace of Western philosophy or longed to unleash your creativity in an inspiring historic setting? We're planning to create events in Athens and other historic locations nearby, tailored for both philosophical exploration and creative writing immersion.

I’ve been talking for years about organizing retreats in Greece. If you’re potentially interested, we’d be very grateful, if you could take a minute to complete our online survey. We need to gather some basic info to help us plan the first event — so we’d like to know what you might be most interested in.

Can you picture yourself surrounded by history and natural beauty, engaging in workshops, discussions, and activities inspired by ancient wisdom?

We’ve already organized or assisted with several very successful events. I now hope to arrange a retreat focused on workshops for a smaller group of people, maybe 6-12,. It would take place in a special location where we can participate in various activities, such as writing, meditation, and philosophical discussion — inspired by ancient Greek philosophy such as Stoicism, and the Socratic dialogues. We haven’t decided where yet but we’ve been looking for a long time at doing events in Delphi, in the heart of Athens, or possibly on the coast just outside the city.

These sorts of retreats could last anything from three to seven days or more, and would be inclusive of accommodation, meals, and other costs. We’d have at least two facilitators — myself and my friend, Lalya Lloyd — but also some guest speakers.

Lalya in a cave - not the intended location of our event!What to expect?

Lalya in a cave - not the intended location of our event!What to expect? (Subject, in part, to your feedback!)

Location: Initially events are planned in Athens, and later in Delphi and on some of the Greek islands, etc.

Duration: Probably 3-7 days of immersive experiences.

Activities: Workshops, discussions, meditation, writing, and excursions to inspiring historic sites.

Facilitators: Donald is a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist and the author of six books on philosophy and psychotherapy, with many years of experience delivering workshops; Lalya is a Greek and Latin classicist who lives in Athens, and is currently working on translations of Plutarch and Seneca’s essays On Tranquillity.

Accommodation and food: All-inclusive with a focus on unique settings. We’re currently looking at options in peaceful areas with access for excursions to Athens and nearby archeological sites, etc.

Donald on Philopappos Hill with the Acropolis of Athens in the background

Donald on Philopappos Hill with the Acropolis of Athens in the backgroundStoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for your help,

Donald Robertson

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 15, 2024

Socrates, Stoicism, and Cognitive Therapy

In this exclusive excerpt from my forthcoming book, How to Think Like Socrates, I discuss how Socrates pre-empted Stoicism and how his philosophical method resembles a form of cognitive psychotherapy.

Pre-Order How to Think Like Socrates

I was astounded to come across ancient Greek dialogues where Socrates was doing something I can only describe as a precursor of cognitive therapy.

It was from Socrates that Stoicism derived some of its most important ideas. The pioneers of cognitive- behavioral therapy (CBT) frequently quote the famous saying of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus that “people are not upset by events but rather by their opinions about them.” The same idea can be found four centuries before Epictetus, though, in the Socratic dialogues. This basic insight into the nature of emotion leads us to the use of reason as a therapeutic technique, as it implies that we should question the assumptions that cause our distress, if we want to get better.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Many different techniques can be used to change our thoughts and beliefs— our “cognitions,” as psychologists call them. The goal of CBT, put simply, is to replace irrational and unhealthy cognitions with rational and healthy ones. One obvious way of doing that is by asking questions, such as:

Where’s the evidence for that?

What are the consequences of that way of looking at things?

How might other people view that situation differently?

Aaron T. Beck, one of the founders of CBT, said that he initially came across this idea when he was studying Plato’s Republic for a college philosophy course. “Socratic questioning,” of this sort, later became a mainstay of his style of therapy. Countless research studies now show that cognitive therapy techniques of this kind, targeting dysfunctional beliefs, can help people suffering from clinical depression, anxiety disorders, and a host of other emotional problems.

As a young therapist in training, I was astounded, nevertheless, to come across ancient Greek dialogues where Socrates was doing something I can only describe as a precursor of cognitive therapy. He behaved like a relationship counselor or family therapist, at times, by helping his friends, and even his own family members, to resolve their interpersonal conflicts. I wondered why no one had ever told me that Socrates was doing cognitive psychotherapy, of sorts, nearly two and a half thousand years before it was supposedly invented.

On one occasion, for instance, Socrates’s teenage son, Lamprocles, was complaining about his notoriously sharp- tongued mother, the philosopher’s fiery young wife, Xanthippe. Socrates, it seemed to me, questioned his son in an incredibly skillful manner. He managed to get Lamprocles to concede that Xanthippe was actually a good mother, who genuinely cared for him. The boy insisted, however, that he still found her nagging completely intolerable. After some discussion, Socrates asked what struck me as an ingenious therapeutic question: Do actors in tragedies take offense when other characters insult and verbally abuse them? As Socrates remarked, they say things far worse than anything Xanthippe ever did.

Lamprocles thought it was a silly question. Of course they don’t take offense, but that’s because they know that despite appearances the other actors do not, in reality, mean them any harm! It’s just make- believe. That’s correct, replied Socrates, but didn’t you admit just a few moments earlier that you don’t believe your mother really means you any harm either?

I’ll leave you to mull this conversation over. I hope you notice how, with a few simple questions, Socrates helped Lamprocles to examine his anger from a radically different perspective. When assumptions that fuel our anger begin to seem puzzling to us, our thinking can become more flexible, and we may begin to break free from the grip of unhealthy emotions. What once seemed obvious, now seems uncertain. Indeed, the brief dialogue that takes place between them encapsulates one of the recurring themes of Socratic philosophy: How can we distinguish between appearance and reality in our daily lives?

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 12, 2024

Stoicism as a Ball Game

There are several recurring metaphors, which the ancient Stoics used to describe their philosophy. One of the most intriguing is that life is like a ball game — or some other game or sport — wisdom and virtue are like “being a good sport”, or being sportsmanlike and playing the game well.

It was the norm for ancient Greek and Roman youths to take part in a variety of sports such as wrestling and ball games. For instance, we’re told of the young Marcus Aurelius:

He was also fond of boxing and wrestling and running and fowling, played ball very skilfully, and hunted well. — Historia Augusta

So it’s not surprising that we find many allusions to such activities in the writings of philosophers. We’re told that Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoic school, was a long distance runner and that he left the Stoa Poikile where his predecessor Cleanthes taught in order to set up his own school in a nearby sports ground called the Lyceum. The Greeks called these areas gymnasia but unlike modern gymnasia they consisted of parks which had pathways for strolling among the trees and by streams, as well as running tracks, wrestling schools, bath houses, and other buildings.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

People would gather there to talk, including the Sophists, who lectured and read speeches in public there. Socrates would also go to the Lyceum to socialize and discuss philosophy. A couple of generations later, Aristotle opened his famous philosophical school in a building there, which became known by the same name. Aristotle’s students were also called Peripatetics because they strolled around the pleasant grounds of the park while discussing philosophy. About a century after Aristotle, Chrysippus also gave open air lectures at the Lyceum, presumably walking past many youths playing sports and exercising.

Indeed, Seneca tells us that it was Chrysippus who introduced the metaphor of the ball game to Stoicism, as an analogy for life in general. The Greeks and Romans played a violent team game called harpastum that involved passing and catching a ball, keeping the opposing team from snatching it, even using some wrestling holds. We don’t know exactly how it was played, but it was perhaps like a distant forerunner of rugby.

Seneca explains that Stoics understand helping or benefiting others by means of this sporting analogy:

I wish to use Chrysippus’ simile of the game of ball, in which the ball must certainly fall by the fault either of the thrower or of the catcher; it only holds its course when it passes between the hands of two persons who each throw it and catch it suitably. It is necessary, however, for a good player to send the ball in one way to a comrade at a long distance, and in another to one at a short distance. — Seneca, On Benefits, 17

A benefit has to be given properly, as it were, and also received properly, just as passing the ball requires one person to throw and another to catch. When attempting to help another person, therefore, according to Seneca we must take into account their ability to receive benefit from us.

If we have to do with a practised and skilled player, we shall throw the ball more recklessly, for however it may come, that quick and agile hand will send it back again; if we are playing with an unskilled novice, we shall not throw it so hard, but far more gently, guiding it straight into his very hands, and we shall run to meet it when it returns to us. — Seneca, On Benefits, 17

Seneca returns to this analogy later:

“A man,” it is argued, “who has received a benefit, however gratefully he may have received it, has not yet accomplished all his duty, for there remains the part of repayment; just as in playing at ball it is something to catch the ball cleverly and carefully, but a man is not called a good player unless he can handily and quickly send back the ball which he has caught.” — Seneca, On Benefits, 32

However, unlike in the ball game, Seneca says that the wise man does not expect to the favours that he bestows on others to be reciprocated.

Epictetus on Life as a Ball GameSeneca’s use of the ball game analogy is interesting, as is the fact he attributes it to Chrysippus. However, Epictetus provides an even more compelling account of the same metaphor. In one of his famous discourses, he uses the ball game to explain how Stoics reconcile emotional detachment with desire, or as he puts it “how magnanimity is consistent with care” (Discourses, 2.5). Epictetus introduces the topic by saying very clearly that although external things are themselves “indifferent”, neither good nor bad, the use we make of them is not — we may use things well or badly, wisely or foolishly, and so on. How can we remain free from emotional disturbance, he asks, while concerning ourselves with external things, such as wealth or reputation?

We can do say, he says, by viewing life as we do a game of dice. The dice are indifferent to us — something trivial and unimportant. I can’t even predict what numbers I’ll roll. My business, in the game, is merely to roll them well and use the numbers that come up. Today we would say that, as in a card game, we must use whatever hand fate deals us, to the best of our ability.

Epictetus says that the chief thing in life is to distinguish carefully between things that are up to us and things that are not. Our own voluntary actions are within our power, he says. We should therefore look for what is good or bad there, in our own conduct, placing more importance on that than upon external events that happen to befall us. What is not up to us, we should call neither good nor bad, beneficial or harmful, etc.

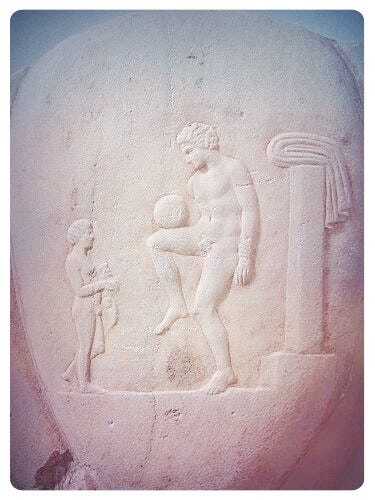

The Stoic Ball Game

The Stoic Ball GameThat’s the essence of Stoic philosophy according to Epictetus and he proceeds to illustrate it with the ball game metaphor, which was apparently introduced to Stoicism three centuries earlier by Chrysippus. Epictetus goes so far as to say that what the Stoic school teaches us about life in general is precisely what anyone does when playing a ball game skilfully.

Nobody playing ball really cares about the ball itself, he says. They try their utmost to seize the ball from the opposing team but they don’t actually think it’s something intrinsically good. They pass it to other team members skilfully but they don’t think the ball is intrinsically bad. It’s just a ball, neither good nor bad. The art of the game consists in throwing and catching the ball quickly, skillfully, and with good judgment. However, if a player was to become overly-attached to the ball so that he didn’t want to pass it to others, or too anxious to catch it and hold on to it then he’d play the game badly. Because he’s not playing his role properly, the other players would start yelling at him to pass the ball instead of hanging on to it and to catch it when they’re trying to throw it to him. “This is quarreling,” says Epictetus, “not play.”

Epictetus immediately follows this analogy by saying “Socrates therefore knew how to play ball.” When he was standing trial and facing execution he continued to play the game of life fearlessly. He cross-examined his accusers philosophically, “as if he were playing ball.”

Life, chains, banishment, a draught of poison, separation from wife and leaving children orphans. These were the things with which he was playing; but still he did play and threw the ball skilfully. — Epictetus, Discourses, 2.5