Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 16

August 10, 2024

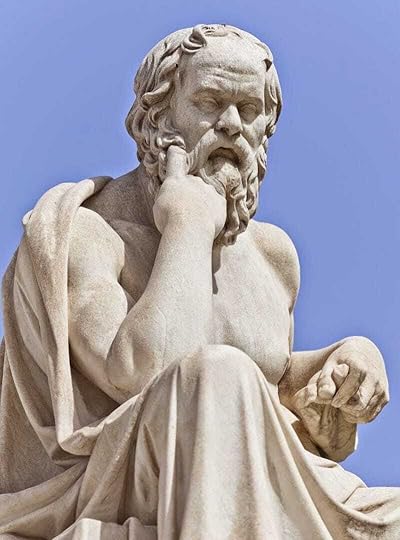

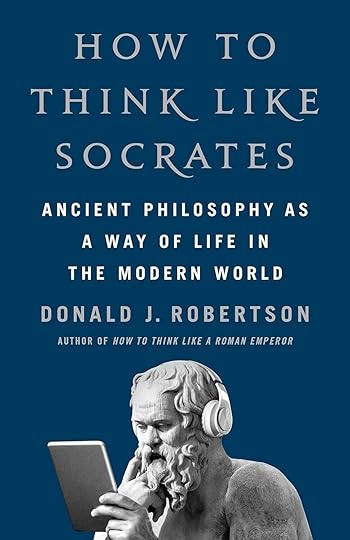

Founder Exclusive: "How to Think Like Socrates"

This is an exclusive for Founding members of my Substack newsletter! I’m delighted to say that my publisher, St Martin’s Press, has generously agreed to provide you with special access, free of charge, to an advance reader copy of my forthcoming book, How to Think Like Socrates. I’m sharing this preview of the book with my Founding subscribers to show…

August 8, 2024

Who was Marcus Aurelius?

In this episode, I’ll be reading a brief excerpt from my new biography, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, which is available as an audiobook as well as in hardback and ebook formats. The book was chosen as an editor’s pick by Barnes and Noble and currently has 4.7 stars on Amazon. You can hear a sample from the studio-recorded audiobook, and read reviews, on Audible. Also see Goodreads for reviews.

“Given the erratic, not to say murderous, behavior of many of [Marcus’s] predecessors, . . . how did so sterling a character as Marcus come about? That is the subject of Donald J. Robertson’s excellent biographical study.”—Joseph Epstein, National Review

“Addictively written, this riveting visitation of the fascinating figure of Marcus Aurelius is as comprehensive as it gets, covering everything from his reign to his philosophy.”—“Notes from Your Bookseller,” barnesandnoble.com

“Eminently readable. . . . A leading light in the modern revival of Stoic philosophy, Robertson directly and elegantly draws out the connections between Marcus’ experiences in the unforgiving crucible of Roman imperial politics and the philosophical ideas he expresses in the Meditations. . . . An invaluable companion to the Meditations itself.”—Peter Juul, Liberal Patriot

“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“[Robertson] thoughtfully and readably capture[s] the essence of this great man and his great life. It’s a must read for any aspiring Stoic.”—Ryan Holiday, coauthor of #1 New York Times bestseller The Daily Stoic

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and Its Modern Significance

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of The Pocket Stoic

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 7, 2024

Special Offer: Upgrade to Founding Member

On Saturday, an email is scheduled to go out to Founding members of this newsletter with news of an exclusive benefit. (All I can say for now is that has to do with my forthcoming book, How to Think Like Socrates.)

If you want to join them, and receive notifications of this and other special offers and exclusive content, as of today, you have the opportunity to upgrade from ordinary Paid to Founding tier subscription for an additional fee of your choosing. Moreover, if you’re not already a paying subscriber, and you sign up before the end of this month for an annual plan, you will receive a one month free trial.

Paying subscribers get access to my regular Behind the Scrolls newsletter containing commentary on passages from classical texts — I’m currently covering the famous Handbook of Epictetus. They can also access the full archive from this newsletter, including the most popular articles I’ve written.

For a trial period, existing Paid tier subscribers will be able to upgrade to become a Founding member of this newsletter for an amount of your choosing. (As long as it exceeds the normal annual fee for paid members.) Hit the button below and choose the “Founding” tier for more information. NB: You will currently be able to edit the amount you want to pay for an annual Founding member subscription.

In addition to other benefits, Founding members receive free access to my eLearning courses on Marcus Aurelius and Socrates. I’ll also be sending out other exclusive benefits for Founding members, including the one the one I’m about to announce on Saturday.

If you want to purchase a subscription for a friend, you can do so using the link below:

Thanks for your support! I hope you enjoy the new content, and look forward to hearing from you in the comments.

Yours sincerely,

Donald Robertson

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 6, 2024

Some Thoughts about Anger

Photo by ARTISTIC FRAMES on Unsplash

Photo by ARTISTIC FRAMES on UnsplashI think our society has a fundamental problem with anger, which is perpetuated by our way of talking and thinking about it. One of the most obvious issues is the way that we all, especially the most angry among us, tend to appeal to the assumption that anger is necessary as a form of motivation. Typically the claim is that we sometimes need anger in order to motivate ourselves to address injustice.

As soon as we accept that it’s possible another emotion could replace anger and achieve the same or better results, the case for justifying anger begins to collapse…

The first thing that should strike us about this claim is that it’s an implicit generalization — it’s the claim that only anger can ever solve these problems. There’s never any alternative. However, generalizations of that sort are very difficult to defend. As soon as we accept that it’s possible another emotion could replace anger and achieve the same or better results, the case for justifying anger begins to collapse, particularly because anger has obvious disadvantages or costs, which other emotions may avoid.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It’s worth detailing the disadvantages of anger at length, of course, because people often overlook or downplay them. However, there are so many that it would be something of a digression here so I’ll just mention one example. It’s well-established from research in cognitive psychology that angry people tend to underestimate risks. Angry people therefore tend to place themselves and others in danger. The consequences of that are very serious for individuals and society. Sometimes, in extreme cases, your anger can get you and even your loved ones killed.

That’s the tip of the iceberg, though. I think most people will intuitively recognize, when they think about the role of anger in history or the anger of others they’ve personally observed, that anger can lead to many other problems. It comes at a high price. So if there’s an alternative, which could motivate us to address injustice, without running those risks, it should be viewed as highly preferable.

The main point I want to address here, though, relates to another specific argument about the nature of anger. People who defend the concept of righteous anger often (but not always) argue that it benefits society by addressing injustice. However, often our actions appear to aim at one goal but, in reality, aim at another. So we have to be careful not to be misled in that regard when evaluating the costs and benefits of anger. Can we define anger, for instance, as an emotion that aims primarily at genuine social justice? Most obviously, anger is associated with the desire to punish another for their perceived transgressions — because they have done something wrong or unjust. Throughout history, therefore, many philosophers have defined anger in terms of a desire for revenge.

Justice punishes those who commit wrongdoing in order to improve them, by deterring them from doing it again. Revenge punishes others for pleasure — the personal gratification we experience from seeing our enemies suffer. Both justice and revenge may employ punishment but for different reasons, and therefore in different ways. Can we honestly say that the primary motivation in anger is to serve justice by improving the person with whom we’re angry? Do angry people mainly want to help others or to harm them?

Let’s turn the question around. Suppose someone primarily wants to improve another person by educating them, or at least using punishment to deter them from future wrongdoing. Could they be described as motivated primarily by anger? The same goes, of course, for our feelings toward groups or society as a whole. Could someone who wants only to help society, or to do it good, be described as motivated only by anger toward society? Or does anger, by its very nature, entail a desire to do harm?

…it is never right to do wrong or to repay wrong with wrong, or when we suffer evil to defend ourselves by doing evil in return.

In Plato's Crito, Socrates asks his oldest friend, after whom the dialogue is named, whether or not one should ever inflict evil, or harm, on other people. Of course not, says Crito. Socrates therefore asks whether it is right, as the whole world says, to repay evil with evil? Crito, who’s surely heard Socrates' argument before, says no. That would be the traditional "Law of Retaliation" (lex talionis) or "an eye for an eye", which stems from a primitive desire for revenge against our enemies.

Doing evil, or harm, to others, continues Socrates, is the same thing as doing them an injustice, which would be wrong. He follows this with a very brief but very striking monologue, worth quoting in full.

“Then we ought to neither return wrong for wrong nor do evil to anyone, no matter what he may have done to us. Be careful though, Crito, that by agreeing with this you do not agree to something you do not believe. For I know that there are few who believe this or ever will. Now those who believe it, and those who do not, have no common ground of discussion, but they must necessarily disdain one another because of their opinions. You should therefore consider very carefully whether you agree and share in this opinion. Let us take as the starting point of our discussion the assumption that it is never right to do wrong or to repay wrong with wrong, or when we suffer evil to defend ourselves by doing evil in return.” — Crito, 49c

Socrates clearly acknowledges this is a paradox — by which the Greeks meant something contrary to popular opinion or contrary to what most people would consider common sense. Nevertheless, Socrates believes that, in a sense, this conclusion should be obvious to us: when we seek primarily to harm others we inevitably make them worse when, in fact, we should be trying to make them better.

Indeed, the Greeks had a popular saying that justice consists in helping our friends and harming our enemies, discussed at length in Book 1 of Plato’s Republic. In that text, the conclusion, though perhaps implied, is never clearly stated. According to the philosopher Plutarch, though, writing centuries later, Socrates was known for saying that rather than seeking to help our friends and harm our enemies a wise, and just, man seeks to do good to his friends and to make friends of his enemies (Plutarch, Spartan Sayings).

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 1, 2024

You are like an actor in a play...

CommentaryRemember that you are an actor in a play, the character of which is determined by the Playwright: if He wishes the play to be short, it is short; if long, it is long; if He wishes you to play the part of a beggar, remember to act even this role adroitly; and so if your role be that of a cripple, an official, or a layman. For this is your business, to play admirably the role assigned you; but the selection of that role is Another’s.

Life is like a play. You’ve been assigned a part and placed on stage. How well you perform your role is up to you, though. Whether it’s long or short is in the hands of fate. You might end up playing anything from a beggar to a statesman, or just a private individual with no specific job. They’re all just different roles that you can fill either badly or well.

July 26, 2024

Stoicism as a Spartan Philosophy of Life

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic philosopher of antiquity, contains a curious passage where the Roman emperor thanks his painting tutor, Diognetus, for having introduced him to philosophy. Marcus says that Diognetus also encouraged him:

[…] to set my heart on a pallet-bed and an animal pelt and whatever else tallied with the Greek regimen. — Meditations, 1.6

The suggestion that Marcus, as a boy, embraced certain austere features of a self-disciplined “Greek” lifestyle is actually confirmed by the Historia Augusta:

[Marcus Aurelius] studied philosophy intensely, even when he was still a boy. When he was twelve years old he embraced the dress of a philosopher, and later, the endurance — studying in a Greek cloak and sleeping on the ground. However, (with some difficulty) his mother persuaded him to sleep on a couch spread with skins. He was also tutored by Apollonius of Chalcedon, the Stoic philosopher […]

That is, when Marcus was only twelve years old, under the guidance of Diognetus, presumably a Greek, he began to adopt a lifestyle described as somehow modelled upon the Greek agoge, a word typically associated with the ancient Spartan training or education for children. Here we’re told that Marcus’ agoge, or regime, involved training in “endurance” (tolerantiam).

From age seven until about thirty, Spartan boys were rigorously trained to become ideal citizens and soldiers. They slept in a mess hall, on military camp beds, and were given only a single garment, a cloak, to wear. They were taught to tolerate hunger and to endure pain and physical discomfort. They were also trained in rigorous physical exercise and the ancient military arts.

They always went without a shirt, receiving one garment [a cloak] for the entire year, and with unwashed bodies, refraining almost completely from bathing and rubbing down. The young men slept together, according to division and company, upon pallets which they themselves brought together by breaking off by hand, without any implement, the tops of the reeds which grew on the banks of the Eurotas. — Plutarch, On the Ancient Customs of the Spartans

Marcus likewise says that his agoge involved, among other things, sleeping on a camp-bed on the ground, like a soldier on campaign, under animal skins rather than soft blankets. The French scholar Pierre Hadot therefore noted the curious similarity between Marcus’ agoge and the Spartan regime:

In his life of the Spartan legislator Lycurgus, Plutarch describes the way in which Spartan children were brought up: once they reached the age of twelve, they lived without any tunic, received only one cloak for the whole year, and slept on mattresses which they themselves had made out of reeds. The model of this style of life was strongly idealised by the philosophers, especially the Cynics and Stoics. — Hadot, 1988, p. 7

Elsewhere, Plutarch describes the Spartan youth as having “hair untrimmed, taking cold baths,” and as eating “coarse bread, and supping on black porridge” (Life of Alcibiades).

The Historia Augusta mentions that as part of the austere lifestyle he adopted in his youth Marcus donned the “Greek cloak” (pallium), traditionally associated with the followers of Socrates, and later Cynic and Stoic philosophers. However, as Hadot notes, this cloak, a single piece of cloth made from grey (undyed) wool, was also traditionally associated with the Spartans.

One might add that the philosophers’ cloak (Greek tribôn, Latin pallium) worn by the young Marcus Aurelius was none other than the Spartan cloak, made of coarse cloth, that had been adopted by Socrates, Antisthenes, Diogenes, and the philosophers of the Cynic and Stoic tradition. — Hadot, 1988, p. 8

The author of the 10th century Byzantine dictionary known as the Suda quotes thirty passages from the Meditations that he refers to as the agoge of Marcus Aurelius, borrowing the word used by Marcus himself in the passage quoted above. Once again, it sounds as though Marcus’ use of Stoicism as a philosophy of life was being compared to aspects of the Spartan training regime and lifestyle.

Cicero takes it for granted that his audience… view the Stoics as having modelled their lifestyle and manner of speaking upon that of the ancient Spartans.

This might seem surprising. However, centuries earlier, during the Roman republic, the orator and philosopher Cicero had mentioned that the Stoics looked and sounded like Spartans. During a legal speech, Cicero explicitly attributed his friend and courtroom opponent Cato’s Stoic practices to “the Spartans, the originators of that way of living and that sort of language” (Pro Murena, 74). Cicero takes it for granted that his audience, including Cato, the “complete Stoic”, view the Stoics as having modelled their lifestyle and manner of speaking upon that of the ancient Spartans.

The Stoics’ were renowned for their concise way of talking as were the Spartans before them. The region surrounding the ancient city of Sparta was known as Lacedaemon, or Laconia, from which comes the adjective “laconic”, still used today to mean an artfully terse manner of speech. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, was particularly known for his abrupt style of speech, and notoriously compressed syllogistic arguments. Once when someone complained that his philosophical arguments were very short, Zeno replied that they were and that if he could he’d make the words shorter as well.

I think brevity was considered a virtue in Stoic philosophy in part because the founders of the school believed that philosophical doctrines should be simple and concise enough to be memorable, and easily recalled in the face of adversity. That happens to be one of the reasons why Stoicism is popular once again today. People find the Stoics eminently quotable and their sayings easy to remember, such as: “Stop arguing what a good man should be and just be one.”

Socrates and Sparta

Socrates and SpartaNow, ancient Sparta was, for the most part, a notoriously brutal regime. The severe training (agoge) they put their young sons through was intended to build courage and self-discipline in preparation for military service. However, I suspect what philosophers from at least the time of Socrates onward intended was to argue that certain aspects of the Spartan training could be adapted for use in a philosopher’s way of life, in the service of developing a character shaped by wisdom, justice, and virtue in general.

We’re told that Socrates definitely thought that his fellow Athenians should model their way of life more on that of their ancestors, or that of the Spartans:

Socrates: “If they [the Athenians] rediscovered their ancestors’ way of life and followed it no worse than they did, they would prove to be just as good men as they were. Alternatively, if they took as their model the present leaders of the Greek world [the Spartans] and followed the same way of life, then with similar application to the same activities they would become no worse than their models, and with closer application they would actually surpass them.” — Xenophon, Memorabilia of Socrates, 3.5

Indeed, in his comedy The Birds, Aristophanes, a contemporary of Socrates, portrays the young Athenian youths who followed Socrates as being obsessed with Sparta (Laconia), and emulating the austere way of life more associated with Spartan youths.

[…] Laconian-mad; they went long-haired, half-starved, unwashed, Socratified with scytales [wooden staffs] in their hands. — Aristophanes, The Birds, 1282

Socrates and his followers were known for their admiration of Sparta, which was controversial because during his lifetime Athens had been conquered and violently oppressed by the Spartans, following the Peloponnesian War.

For example, Plato’s Crito, which depicts the scene in the Athenian prison as Socrates awaits execution, mentions his great admiration for the laws of Sparta and Crete, which he was “always saying are well-governed”. In the Republic Plato likewise portrays Socrates claiming that the constitutions of Crete and Sparta represent the best forms of government, superior to that of Athens. One of Socrates’ most influential students, Xenophon, fled from Athens to Sparta and spent the rest of his life there. He wrote a treatise about Spartan society called On the Lacedaemonian Constitution. Plutarch likewise tells us that one of Socrates’ most austere students, Antisthenes, who is traditionally seen as the founder or at least inspiration for the later Cynic tradition, held Spartan society in particularly high regard.

The Cynics and Stoics on Sparta

The Cynics and Stoics on SpartaThe Cynic and Stoic philosophers who came later were therefore greatly influenced by Socrates and apparently shared his admiration for aspects of Spartan education system, seeking to wed training in self-discipline with the study of philosophy.

A generation after Socrates, Diogenes the Cynic was known so much for praising the Spartan way of life that it’s said an Athenian once asked him sarcastically why he didn’t go and live among them instead, to which he replied that a doctor doesn’t carry out his role among the healthy (Stobaeus, 3.13). We’re likewise told that when asked where in Greece he had found good men, Diogenes answered “Men nowhere at all, but boys in Sparta”, as though he thought the agoge should be a lifelong training (Diogenes Laertius, 6.27). Again, when returning from a trip to Sparta, someone asked him where he was going, and Diogenes, exhibiting the typical sexism of his era, answered: “From the men’s quarters to the women’s.” (Diogenes Laertius, 6.59).

The Cynics famously referred to their Spartan-style training in endurance as “voluntary hardship.” We’re told, for instance, of Diogenes the Cynic:

In the summer he used to roll in the sand, and in the winter embrace snow-covered statues, using every means to train himself to endure hardship… — Diogenes Laertius

However, the Spartans were apparently unimpressed by these public displays of endurance, and taught Diogenes that once he’d mastered such feats he needed to keep finding new challenges.

On seeing Diogenes the Cynic embracing a bronze statue in extremely cold weather, a Spartan asked him whether he was feeling chilly; and when he replied no, the Spartan said, ‘Then what’s so wonderful in what you’re doing?’ — Plutarch, Spartan Sayings

It seems that, like Socrates, the Cynics were perceived as modelling themselves on the Spartans, taking aspects of the agoge’s training in endurance and self-discipline and employing them in the service of philosophy as a way of life, the cultivation of a more general type of wisdom and virtue

Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, had originally been a Cynic philosopher, and in many ways the Stoics resembled their predecessors the Cynics, including their interest in philosophical training influenced by the Spartan agoge. In his Studies in Stoicism (2013), the scholar P.A. Brunt wrote “Old Sparta apparently evoked Stoic admiration, because of the strict and simple life prescribed by Lycurgus” (p. 287). The Stoics, like many Hellenistic philosophers, particularly admired Lycurgus (820–730 BC) the semi-mythical founder of the Spartan constitution and the agoge.

There’s no doubt that the Stoics were particularly interested in studying the original Spartan laws and education system. Plutarch wrote a biographical account of Lycurgus in which he claims that his Spartan constitution was the inspiration for the ideal societies described by Diogenes and in Zeno in their books both entitled The Republic. Cleanthes, the second head of the Stoa, wrote a book entitled On Agoge, which perhaps contained an early Stoic appraisal of the Spartan education system. Persaeus and Sphaerus, two of Zeno’s most important Stoic students, both wrote books called On the Spartan Constitution. Sphaerus also wrote three volumes titled On Lycurgus and Socrates.

Moreover, according to Plutarch, Sphaerus went to Sparta to train the youth who would become King Cleomenes III in Stoic philosophy, which he did “with great diligence and success”. We’re told that Sphaerus greatly admired Cleomenes’ strength of character. Whereas the famous Spartan king Leonidas had once said that certain poetry could inspire Spartan youth to courage in battle, Sphaerus’ inspired Cleomenes’ and other Spartan youths to virtue and the love of glory through his lectures in Stoic philosophy. Presumably, because of his initial success in this regard, Sphaerus then proceeded to assist Cleomenes’ later attempts to restore the agoge after it had fallen into decline (Brunt, p. 91).

Socrates therefore had been an admirer of the Spartan agoge as were several of his most important students, the Cynics, and the early Stoics who came after them. These aspects of Spartan training apparently continued to influence the characteristic way of life adopted by Cynic and Stoic philosophers right down to the time of the Roman empire.

The Roman Stoics on the Spartan Lifestyle

The Roman Stoics on the Spartan LifestyleMarcus Aurelius writes, in a private letter to his rhetoric tutor and family friend Fronto:

Then we went to luncheon. What do you think I ate? A wee bit of bread, though I saw others devouring beans, onions, and herrings full of roe.

In another letter, Fronto says that he saw one of Marcus’ young sons holding “a piece of black bread, quite in keeping with a philosopher’s son.”

Eating cheap unhusked bread or barley-bread was something associated with the Cynic tradition and probably therefore with some Cynic-influenced Stoics. For example, one Cynic letter says: “It is not only bread and water, and a bed of straw, and a rough cloak, that teach temperance…” We’re told of Crates, the Cynic teacher of Zeno, who abandoned his fortune: “Having adopted simpler ways, he was contented with a rough cloak, and barley-bread, and vegetables, without ever yearning for his former way of life or being unhappy with his present one.”

Whereas the Cynics were known for mainly drinking water and eating coarse bread, lentils, and lupin seeds, we have a surviving lecture from Musonius Rufus, the teacher of Epictetus, who says that Stoics should prefer food that’s healthy and easy both to obtain and to prepare, such as “fruits in season, certain vegetables, milk, cheese, and honeycombs.” In any case, it’s clear that philosophers in the Cynic-Stoic tradition believed in following a simple diet, although perhaps not as severely restricted as that of the original Spartan agoge whose youths dined on the notorious black broth, made from pig’s blood.

Musonius Rufus nevertheless says that a youth brought up “in a somewhat Spartan manner”, who is not accustomed to soft living, will be more able to absorb the Stoic teachings that death, pain, and poverty are not evils and their opposites are not good (Lectures, 1). He links this to an anecdote about Cleanthes, the second head of the Stoa, and a Spartan boy, who had been trained well for virtue and therefore easily grasped Stoic philosophy at a practical level. Elsewhere he tells his students that Spartan boys who are whipped in public without shame or feelings of injury set a good example for Stoics, insofar as philosophers must be able to scorn blows and jeering, and ultimately even death (Lectures, 10).

Indeed, he praised Lycurgus as one of the greatest of all law-makers, because of the austere training he instigated for Spartan youths, which Musonius encourages his own students to emulate.

Consider the greatest of the law-givers. Lycurgus, one of the foremost among them, drove extravagance out of Sparta and introduced thriftiness. In order to make Spartans brave, he promoted scarcity rather than excess in their lifestyle. He rejected luxurious living as a scourge and promoted a willingness to endure pain as a blessing. That Lycurgus was right is shown by the toughness of the young Spartan boys who were trained to endure hunger, thirst, cold, beatings, and other hardships. Raised in a strict environment, the ancient Spartans were thought to be and in fact were the best of the Greeks, and they made their very poverty more enviable than the king of Persia’s wealth. — Lectures, 20

Musonius’ most famous student was Epictetus, who became an influential Stoic teacher in his own right. Indeed, Epictetus is the only Stoic teacher whose teachings survive today in book-length, although half of the Discourses recorded by his student Arrian are lost. We have a fragment from the anthologist Stobaeus in which either Epictetus or Musonius Rufus — the attribution is unclear — is seen also to praise the personal example set by Lycurgus:

Spartan SayingsWho among us is not amazed at the action of Lycurgus the Spartan? When a young man who had injured Lycurgus’ eye was sent by the people to be punished in whatever way Lycurgus wanted, he did not punish him. He instead both educated him and made him a good man, after which he led him to the theatre. While the Spartans looked on in amazement, he said: “This person I received from you as an unruly and violent individual. I give him back to you as a good man and proper citizen.” — Stobaeus, 3.19.13

The ancient Spartans were known, as we’ve seen for their brevity of speech. However, they combined this with a certain type of succinct wisdom, which philosophers such as the Stoics and Cynics greatly admired. The philosopher Plutarch gathered together many of their remarks in Sayings of Spartans. Elsewhere Plutarch explains:

They learned to read and write for purely practical reasons; but all other forms of education they banned from the country, books and treatises being included in this quite as much as men. All their education was directed toward prompt obedience to authority, stout endurance of hardship, and victory or death in battle. — The Ancient Customs of the Spartans

First of all, the Spartans, like the Stoics, prized good character and self-discipline. When someone said, for instance, that the Spartan Alcamenes lived a very austere life although he owned plenty of property, he said, “Yes, for it is a noble thing for one who possesses much to live according to reason and not according to his desires.” Character is more important than property. When some people were amazed at the costliness of the raiment found among the spoils of the barbarians, the Spartan Pausanias said that it would have been better for them to be themselves men of worth than to possess things of worth. The Spartans were also doubtful whether intellectuals of the sort that flourished at Athens had much of value to teach them. When asked why he didn’t admit one of the most learned men of the time to his presence, the Spartan king Agasicles reputedly said: “I want to be a pupil of those whose son I should like to be as well.”

The Spartans therefore thought that Athenian philosophers such as the followers of Plato’s Academy talked too much about virtue without actually training themselves to have virtuous characters. When the Spartan Eudamidas saw the elderly head of Plato’s Academy, Xenocrates, discussing philosophy, he inquired who the old man was. Somebody said that he was a wise philosopher who was seeking virtue. “And when will he use it,” said Eudamidas, “if he is only now seeking for it?” Likewise, when the philosophers in the Academy were conversing long and seriously, and afterwards some people asked the Spartan Panthoidas how their conversation impressed him, he said, “What else than serious? But there is no good in it unless you put it to use.” This “cynical” attitude toward the Academy, and other overly-verbose philosophers, was shared by the Cynics.

The Spartans thought that too much talking was a vice. An orator who asserted that he could speak the whole day long on any topic whatsoever, they expelled from the country, saying that a good speaker must keep his discourse equal to the subject in hand. Likewise, an ambassador who had come to Sparta made a long speech. When he had stopped speaking and asked Agis what report he should make to his people, the Spartan said, “What else except that it was hard for you to stop speaking, and that I said nothing?” Antalcidas, when a lecturer was about to read a laudatory essay on Heracles, said, “Why, who says anything against him?” When somebody found fault with Hecataeus the Sophist because, when he was received as a member at the common table, he spoke not a word, Archidamidas said, “You do not seem to realize that he who knows how to speak knows also the right time for speaking.” In a council meeting Demaratus was asked whether it was due to foolishness or lack of words that he said nothing. “But a fool,” said he, “would not be able to hold his tongue.”

Lochagus, the father of Polyaenides and Seiron, when word was brought to him that one of his sons was dead, said, “I have known this long while that he was fated to die.” Similar remarks are attributed to Xenophon and others. These perhaps influenced the Stoic Epictetus’ notorious advice “If you are kissing your child or wife, say that it is a mortal whom you are kissing, for when the wife or child dies, you will not be disturbed” (Encheiridion, 2).

Being asked how one could be a free man all his life, Agis said, “By feeling contempt for death.” Anaxandridas was asked why the Spartans, in their wars, ventured boldly into danger, and he replied, “Because we train ourselves to have regard for life and not, like others, to be timid about it.” When Philip of Macedon invaded the Peloponnese, and someone exclaimed, “There is danger that the Spartans may meet a dire fate if they do not make terms with the invader,” Damindas replied, “What dire fate could be ours if we have no fear of death?” Likewise when Antipater made dire threats against the Spartans if they didn’t comply with his demands, they answered, “If the orders you lay upon us are harsher than death, we shall find it easier to die.”

The Spartans also believed that they should train themselves to act decisively but without anger clouding their judgment.

Moreover the rhythmic movement of their marching songs was such as to excite courage and boldness, and contempt for death; and these they used both in dancing, and also to the accompaniment of the flute when advancing upon the enemy. In fact, Lycurgus coupled fondness for music with military drill, so that the over-assertive warlike spirit, by being combined with melody, might have concord and harmony. — Plutarch, On the Ancient Customs of the Spartans

In other words, although fierce in battle, Spartans did not allow either fear or anger to govern their actions. When one of the Helots, or slaves, conducted himself rather boldly toward the Spartan Charillus, for instance, he said, “If I were not angry, I would kill you.”

When someone commended to Ariston the maxim of Cleomenes, who, on being asked what a good king ought to do, said, “To do good to his friends and evil to his enemies,” Ariston said, “How much better, my good sir, to do good to our friends, and to make friends of our enemies?” This, which is universally conceded to be one of Socrates’ maxims, is also referred to Ariston, says Plutarch. (Socrates famously disputes this traditional definition of justice in Book One of Plato’s Republic.)

July 25, 2024

News about forthcoming projects

I’ve been very busy this year. My son, Hector, was born in November, so it’s been a challenge writing with a newborn in the house — my office has become his nursery and I’ve started working from an office in a nearby building instead. I have a few projects to announce, though, which I’ll tell you about below.

First, though, I wanted to mention that if you want to receive updates from Amazon as soon as a new book becomes available, you can simply go to my author profile page and click on the follow button there. That’s a good way to make sure you don’t miss any new releases.

It’s unusual for an author to have two books published in the same year but, partly because of the knock-on effect of the pandemic, etc., I had one new book that came out in February and another that will be released in November.

Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, from Yale University Press

How to Think Like Socrates, from St Martin’s Press

If you’re interested in the Socrates book, please consider preordering it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble. When readers do that it encourages retailers to promote the book a bit more and helps it to reach a wider audience. (Amazon also have a preorder price guarantee that means you can have more chance to save money the earlier you order your copy!)

I also recently contributed a foreword to The Stoicism Workbook co-authored by my wife, Kasey Pierce, along with the clinical psychologists Scott Waltman and R. Trent Codd.

I will also be working on a new book soon for Princeton University Press with my friend, the classicist and translator, Lalya Lloyd. It will contain translations of two texts, one Greek and the other Latin, from Plutarch and Seneca respectively, both known as On Tranquillity. This will be the first time that both texts have been published in the same volume. I think it’s a great opportunity to compare the advice they give for coping with anxiety and developing emotional resilience — one from a Platonist and the other from a Stoic. I will be writing about how their advice compares to the sort of things we do in modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT).

I’ve also been asked to record a series of audio lessons, and meditation exercises, for Sam Harris’ Waking Up app. These will explore how Stoicism can be used on a daily basis to develop emotional resilience.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for following me on Substack, and please feel free to get in touch if you have any questions about these or other projects.

Regards,

Donald Robertson

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

July 22, 2024

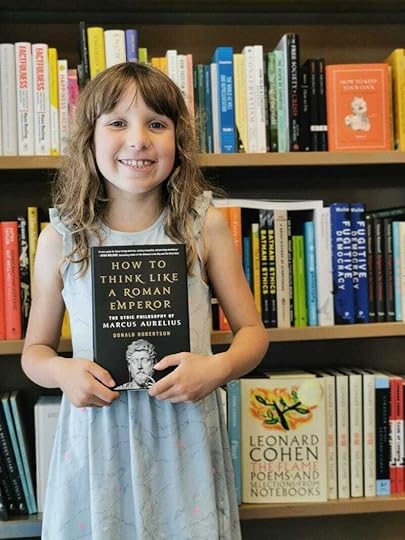

Poppy on Socrates and Stoicism

This is an excerpt from How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

My daughter, Poppy Robertson, aged eight.

My daughter, Poppy Robertson, aged eight.A few years ago, when my daughter Poppy was four, she began asking me to tell her stories. I didn’t know any children’s stories, so I told her what came to mind: stories about Greek myths, heroes, and philosophers. One of her favorites is about the Athenian general Xenophon. Late one night, as a young man, he was walking through an alleyway between two buildings near the Athenian marketplace. Suddenly a mysterious stranger, hidden in the shadows, blocked his path with a wooden staff. A voice inquired from the darkness, “Do you know where someone should go if he wants to buy goods?”

Where should one go in order to learn how to become a good person?

Xenophon replied that they were right beside the agora and the finest marketplace in the world. There you could buy any goods your heart desired: jewelry, food, clothing, etc. The stranger paused for a moment before asking another question: “Where, then, should one go in order to learn how to become a good person?” Xenophon was dumbstruck. He had no idea how to answer. The mysterious figure then lowered his staff, stepped out of the shadows, and introduced himself as Socrates. Socrates said that they should both try to discover how someone could become a good person, because that’s surely more important than knowing where to buy all sorts of other goods. So Xenophon went with him and became one of his closest friends and followers.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I told Poppy that most people believe there are lots of good things — nice food, clothes, houses, money, etc. — and lots of bad things in life, but Socrates said perhaps they’re all wrong. He wondered if there was perhaps only one good thing, and if it was inside of us rather than outside. Maybe it was something like wisdom or bravery. Poppy thought for a minute, then, to my surprise, she shook her head, saying, “That’s not true, Daddy!” which made me smile. Then she said something else: “Tell me that story again,” because she wanted to continue to think about it. She asked me how Socrates became so wise, and I told her the secret of his wisdom: he asked lots of questions about the most important things in life, and then he listened very carefully to the answers. So I kept telling stories, and she kept asking lots of questions. As I came to realize, these little anecdotes about Socrates did much more than just teach her things. They encouraged her to think for herself about what it means to live wisely.

One day, Poppy asked me to write down the stories I was telling her, so I did. I made them longer and more detailed, then I read them back to her. I started sharing some of them online, via my blog. Telling her these stories and discussing them together made me realize that this was, in many ways, a better approach to teaching philosophy as a way of life. It allowed us to consider the example set by famous philosophers and whether or not they provide good role models. I began to think that a book that taught Stoic principles through real stories about its ancient practitioners might prove helpful not just to my little girl but to other people as well.

Next, I asked myself who was the best candidate I could use as a Stoic role model, about whom I could tell stories that would bring the philosophy to life and put flesh on its bones. The obvious answer was Marcus Aurelius. We know very little about the lives of most ancient philosophers, but Marcus was a Roman emperor, so far more evidence survives about his life and character. One of the few surviving Stoic texts consists of his personal notes to himself about his contemplative practices, known today as The Meditations. Marcus begins The Meditations with a chapter written in a completely different style from the rest of the book: a catalogue of the virtues, the traits he most admired in his family and teachers. He lists about sixteen people in all. It seems he also believed that the best way to begin studying Stoic philosophy is to look at living examples of the virtues. I think it makes sense to view Marcus’s life as an example of Stoicism in the same way that he viewed the lives of his own Stoic teachers.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

July 17, 2024

Get "How to Think Like a Roman Emperor" for $2.99

If you haven’t already got a copy, or have just listened to the audiobook, you might want to snap up How to Think Like a Roman Emperor for only $2.99. It’s been selected as an Amazon Prime Day Deal in the US and is on sale for one day only at this special discount price.

My publisher tell me that other retailers generally downprice ebooks to match Amazon's pricing as well. So even if you’re outside the US or want to buy buy it on another platform you may still be able to find it on sale today! Amazon Canada and Barnes & Noble, for instance, also have the ebook on sale for $2.99 today only.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Popular QuotesAmazon has an interesting feature that allows us to see the passages most often highlighted by Kindle readers. Here are the top three:

“What matters, in other words, isn’t what we feel but how we respond to those feelings.” — highlighted by 3,713 Kindle readers

“To learn how to die, according to the Stoics, is to unlearn how to be a slave.” — highlighted by 3,549 Kindle readers

“The Stoics adopted the Socratic division of cardinal virtues into wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation.” — highlighted by 3,037 Kindle readers

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

July 15, 2024

The Three Classic Books on Stoic Philosophy

Let these doctrines, if that is what they are, be enough for you. As for your thirst for books, be done with it, so that you may not die with complaints on your lips, but with a truly cheerful mind and grateful to the gods with all your heart. — Meditations, 2.3

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, like other Stoics, believed that it was more important to apply philosophy in practice, throughout our daily lives, than simply to read about it in books. However, he also owned a copy of the Discourses of Epictetus, gifted to him by his Stoic mentor Junius Rusticus, which he quotes repeatedly and had clearly studied very closely indeed.

You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works…

The philosopher Seneca explains the Stoic attitude toward reading as being more about quality than quantity:

Be careful, however, lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere. When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends. And the same thing must hold true of men who seek intimate acquaintance with no single author, but visit them all in a hasty and hurried manner. — Letters to Lucilius, 2

When Jeff Beck sang “You’re everywhere and nowhere, baby”, in Hi Ho Silver Lining, he could have been quoting Seneca.

The Stoic advises his friend Lucilius that people who constantly change the medicine they’re taking get little benefit. We should identify the most valuable books and study them very closely, reading them repeatedly, rather than behaving like a dilettante and dipping first into one book and then another without allowing ourselves the time to properly digest any of the ideas they contain, let alone put them into practice.

Below I’ve listed the most important books on Stoicism, at least as far as I’m concerned. (I’ve grouped them under three main headings, by author, although you’ll notice that I’ve sneakily mentioned more than one text in some cases.) If you’re interested in Stoicism you should probably read these over and over again until you know many of the passages by heart.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Some of you will already have read these books so I wanted to add some anecdotes about the historical context in which they were written. That’s the approach I adopted when writing How to Think Like a Roman Emperor and my forthcoming book, How to Think Like Socrates. I repeatedly found over the years, running courses and workshops on Stoicism, that people tended to get far more benefit out of the classical texts if they read them closely and understand more about the author and their times.

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius

The Meditations of Marcus AureliusThis is the first book most people read on Stoicism. It consists of the personal notes or journal kept by the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. From two brief remarks in the text, and some other minor clues, it appears he probably wrote most or all of the text toward the middle or end of the First Marcomannic War, probably sometime between 170 and 175 AD. For instance, Meditations mentions some time having passed since the death of his adoptive brother, Lucius, in 169 AD, but there’s no mention of Marcus’ wife, Faustina, having passed, as she died later in 176 AD.

After the untimely death of his brother and co-emperor, Lucius Verus, Marcus, apparently with no military training or experience whatsoever, donned the general’s cape and boots and rode out to take sole command of the largest army ever massed on a Roman frontier — numbering roughly 140,000 men in total.

Following the Parthian War a devastating disease, known as the Antonine Plague, swept through the empire, particularly the legionary camps, leaving Rome highly vulnerable. Ballomar, the young king of the Marcomanni, seized his opportunity to spring a surprise attack and, in breach of existing peace treaties, led a huge coalition of hostile barbarian tribes across the River Danube, overrunning the northern provinces of the empire. The Marcomanni and their allies proceeded to loot and pillage their way across the Alps and finally laid siege to the prosperous Italian city of Aquileia, bringing war to the very doorstep of Rome herself, and throwing the city into panic.

After driving the enemy out of Italy and liberating the northern provinces, for much of the ensuing war, Marcus stationed himself at the front line, in the Roman legionary fortress of Carnuntum, beside the Danube. It was in the crucible of this gruelling war that The Meditations took shape. My belief is that Marcus may have been inspired to begin writing down his personal reflections on applying philosophy in daily life following the death of his beloved Stoic tutor, Junius Rusticus, around 170 AD — possibly another victim of the plague. Deprived of his closest friend and mentor, Marcus became his own Stoic therapist, as it were, and worked through his emotions by writing short reflections, some of which were probably fragments of remembered conversations with his Stoic teachers.

In one of the most famous passages of the Meditations, which opens the main part of the book, Marcus reminds himself to prepare each morning to face dishonesty and treachery. The manuscript of the Meditations originally bore the title To Himself and this, the main part of the text, opens with the words “Say to yourself…”

Say to yourself at the start of the day, I shall meet with meddling, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, and unsociable people. They are subject to all these defects because they have no knowledge of good and bad. But I, who have observed the nature of the good, and seen that it is the right; and of the bad, and seen that it is the wrong; and of the wrongdoer himself, and seen that his nature is akin to my own — not because he is of the same blood and seed, but because he shares as I do in mind and thus in a portion of the divine — I, then, can neither be harmed by these people, nor become angry with one who is akin to me, nor can I hate him, for we have come into being to work together, like feet, hands, eyelids, or the two rows of teeth in our upper and lower jaws. To work against one another is therefore contrary to nature; and to be angry with another person and turn away from him is surely to work against him. — Meditations, 2.1

Most people assume he’s talking about petty matters but Marcus also faced some massive, historic, acts of betrayal, such as the conspiracy leading to the Marcomanni invasion described above. This passage seems all the more remarkable, doesn’t it, if we stop to consider whether this was how Marcus looked upon the enemy tribes he was waging war against?

Meditations is a very easy book to read but in my experience people do obtain much more from it when they study the text more closely, and learn a little more about the historical and philosophical context in which it was written. That’s why I wanted to write a book about Marcus Aurelius that linked the inner story of his life, as a philosopher, as found in the Meditations, with the stories of his outer life, as Roman emperor, as told in several Roman histories of his reign, and a few other ancient sources that we still have today.

The Handbook and Discourses of Epictetus

The Handbook and Discourses of EpictetusThe next book about Stoicism that most people should read is the Handbook or Enchiridion of Epictetus, which is actually a series of fifty three sayings and short passages based on the Discourses, compiled and edited by his student Arrian, a highly-accomplished Roman statesman and general. It’s an obvious choice because it’s short and easy to read. It was specifically designed by Arrian to provide a simple, practical introduction to Stoicism, almost like a bullet-point summary of the much longer Discourses.

Marcus Aurelius also quotes repeatedly from the Discourses and he seems to be mainly following Epictetus’ brand of Stoicism. So if you like the Meditations, you’ll almost certainly like the Handbook as well. And if you like the Handbook, you’ll probably like the longer and more discursive version of the same ideas found in the Discourses.

According to some ancient sources there were originally eight volumes of the Discourse of Epictetus. Unfortunately, only four actually survive today. Intriguingly, though, Marcus Aurelius says that he was given a copy of notes from the lectures of Epictetus by his tutor Junius Rusticus. (Marcus was a young boy when Epictetus died and they’d almost certainly never met in person.) As Marcus later quotes from the surviving Discourses we can be fairly certain those are the notes to which he’s referring. However, he also quotes otherwise unknown sayings of Epictetus, which suggests he’d perhaps also read the four lost volumes of the Discourses. In fact, for all we know some of the other passages scattered throughout the Meditations could be quotes or paraphrases from these missing books of Epictetus.

The most famous passage in the Handbook says that it’s not things that upset us but our judgments or opinions about them. Although this became to be seen as a typically Stoic idea, it can actually be traced back to Socrates, the philosopher whom the Stoics most admired and sought to emulate. Indeed, Epictetus hints at this by immediately bringing in Socrates as an example:

Men are disturbed not by the things which happen, but by the opinions about the things: for example, death is nothing terrible, for if it were, it would have seemed so to Socrates; for the opinion about death, that it is terrible, is the terrible thing. — Handbook, 5

The first part of that quote encapsulates what psychologists now call the “cognitive theory of emotion”. (It’s our thoughts and beliefs, aka “cognitions”, that largely determine our emotions.) It was adopted by Albert Ellis, one of the pioneers of cognitive therapy, in the 1950s, who taught it to most of his clients in their initial session. Hence, it became well-known, almost a cliche, to subsequent generations of cognitive-behavioural therapists.

The second most famous passage from the Handbook is its very first sentence: “Some things are up to us whereas other things are not” (Handbook, 1). There’s clearly a good reason why Arrian chose that as the opening sentence: it’s the foundation of everything that follows. The Stoics believed that we need to train ourselves throughout life to carefully distinguish between things that are directly under our control and everything else.

This concept also became famous through The Serenity Prayer, popularized by Alcoholics Anonymous: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference.” Today Stoics tend to call this idea the “Dichotomy of Control”, and I also tend to describe it as the “Stoic Fork” because it involves making a sharp distinction between two domains in life: what we do and what merely happens to us.

Seneca’s Letters to Lucilius

Seneca’s Letters to LuciliusSeneca came from the generation before Epictetus. Curiously, neither Marcus nor Epictetus mention him. That appears to be partly because of a convention whereby Romans writing in Greek (like Marcus and Epictetus) didn’t tend to cite Latin authors. However, there may be another explanation.

Seneca was rhetoric teacher to the young Emperor Nero and later became his speechwriter and political advisor. It might even be reasonable to refer to him as a professional Sophist, rather than a philosopher. Despite Seneca’s guidance, in adulthood Nero quickly degenerated into a violent despot and began murdering his own family members, and persecuting his opponents. At first Seneca continued to support him, often seeming to apologize for and defend his behaviour. However, later he withdrew from public life and eventually Nero had him executed on a seemingly trumped up conspiracy charge.

I said that Marcus doesn’t mention Seneca in Greek but we also have a surviving cache of letters between Marcus and his Latin rhetoric tutor, Fronto. In these, Fronto several times mentions Seneca, in a manner that seems derisive. At one point he even goes so far as to warn Marcus that looking for pearls of philosophical wisdom in the writings of Seneca is like grubbing around in the bottom of a sewer just to retrieve a few silver coins.

We don’t really see Marcus’ response to this. My guess is that they may have been talking about political speeches by Seneca rather than the philosophical letters he’s best known for today. We get a glimpse of what these may have been like in texts such as On Clemency, where Seneca awkwardly defends Nero, portraying him as a virtual philosopher-king without a drop of blood on his hands, etc. This claim would have been laughable to the Senate and to subsequent generations, who recognized Nero as a violent despot. Indeed, Marcus, in the Meditations, only mentions Nero to use him as an example of a despotic and violent individual. Moreover, Epictetus warns his students against flattering tyrants, presumably such as Nero. It would be an interesting thought experiment, therefore, to imagine how Epictetus might have responded to the praise of Nero found in Seneca’s On Clemency. He had originally been a slave owned by one of Nero’s secretaries and may well have witnessed first-hand the intrigue and chaos surrounding the imperial court at this time.

During Nero’s reign a group of politicians known as the “Stoic Opposition” adopted a principled stance against him, led by Thrasea, a close friend of the famous Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus, whose student Epictetus would later become. These men criticized Nero more openly than Seneca dared. When Nero sent the Senate a letter trying to excuse the murder of his own mother by claiming that she had been discovered plotting against him and had committed suicide Thrasea silently walked out of the meeting. These acts of peaceful protest undoubtedly provoked Nero’s wrath.

And indeed this was always his way of acting on other occasions. He used to say, for example:

If I were the only one that Nero was going to put to death, I could easily pardon the rest who load him with flatteries. But since even among those who praise him to excess there are many whom he has either already disposed of or will yet destroy, why should one degrade oneself to no purpose and then perish like a slave, when one may pay the debt to nature like a freeman? As for me, men will talk of me hereafter, but of them never, except only to record the fact that they were put to death. — Cassius Dio

It seems difficult to imagine that Thrasea did not primarily have Seneca in mind here, albeit perhaps among others. That would certainly explain why no later Stoics are known to have mentioned his name. Epictetus and Marcus, however, both heap praise on members of the Stoic Opposition. Indeed, the Handbook concludes with a quote attributed to Socrates which says “Anytus and Meletus can kill me but they cannot harm me”, referring to the two key individuals who brought the charges leading to his execution. (It’s perhaps a paraphrase from Plato’s Apology.) Epictetus’ students must have recognized that as a tribute to Thrasea because Cassius Dio tells us that he was famous for applying the same saying to Nero: “Such was the man that Thrasea showed himself to be; and he was always saying to himself: ‘Nero can kill me, but he cannot harm me.’”

Despite his murky political leanings, though, and pace Fronto, Seneca’s philosophical writings do contain a great deal of valuable Stoic wisdom. The Letters to Lucilius, of which there are 124, are the most common place for people to start. They’re beautifully written and provide an excellent introduction to Stoicism as a philosophy of life. They read more like essays and so in some ways they’re more accessible than either the discourses of Epictetus or notes of Marcus Aurelius

If you like those, you should read Seneca’s other letters and essays, perhaps starting with the consolation letters to Marcia, Helvia, and Polybius. These are important examples of the consolatio genre in philosophical literature, in which philosophical advice is given to a friend in order to help them assuage emotional suffering. They illustrate, in other words, a form of Stoic psychotherapy or counselling. Epictetus mentions that one of his heroes, a member of the Stoic Opposition called Paconius Agrippinus, used to write letters of this kind addressed to himself when faced with some personal catastrophe. In some respects, we can also see the Meditations (“To Himself”) of Marcus Aurelius as resembling a consolation letter addressed to himself, although written in the form of fragmentary passages rather than continuous prose.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.