Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 14

September 30, 2024

What Nobody Tells You About Breaking Habits

If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise. — William Blake, Proverbs of Hell

Most people who want to eliminate their bad habits try to do so by directly suppressing them — just forcing themselves to stop. Often they find that simply doesn’t work. In his novel Women in Love, D.H. Lawrence gives a truly remarkable description of the opposite technique:

“A very great doctor taught me”, [Hermione] said, addressing Ursula and Gerald vaguely. “He told me for instance, that to cure oneself of a bad habit, one should force oneself to do it, when one would not do it — make oneself do it — and then the habit would disappear.”

“How do you mean?” said Gerald.

“If you bite your nails, for example. Then, when you don’t want to bite your nails, bite them, make yourself bite them. And you would find the habit was broken.”

“Is that so?” said Gerald.

“Yes. And in so many things, I have made myself well. I was a very queer and nervous girl. And by learning to use my will, simply by using my will, I made myself right.” — Women in Love, 1920

Knight Dunlap

Knight DunlapA similar method for breaking bad habits was developed in the 1920s by Knight Dunlap, Professor of Experimental Psychology at Johns Hopkins University and president of the American Psychological Association (APA). Dunlap’s method, known as “negative practice”, was described in his all but forgotten Habits: Their Making and Unmaking (1932). Dunlap was, without question, a man far ahead of his time in the field of psychotherapy, whose ideas in some ways anticipated modern cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

The Beta Hypothesis: Intention Matters

The Beta Hypothesis: Intention MattersWe normally assume, of course, that “practice makes perfect” and that repeating a habit makes it stronger. We can call that the “alpha hypothesis” (hypothesis a) concerning habits. Dunlap contrasted that with his “beta hypothesis” (hypothesis b), which says that under certain conditions voluntarily engaging in your habit can have the paradoxical effect of making it weaker, perhaps even eliminating it completely.

Dunlap’s hypothesis was that your attitude is key. “In negative practice”, he wrote, “the determining factors are the thoughts and desires in the practice.” If you’re repeatedly performing some action with the intention of making it a habit then, with practice, you may well succeed. However, if your intention is to weaken an existing habit that’s what tends to happen.

Dunlap’s favorite example comes from a method he noticed being used to train typists:

The non-professional typist and the learner frequently make persistent errors, such as the transposition of the into hte, and these errors are ordinarily eliminated with difficulty. It has been found, however, that even a small amount of practice in writing the word in the wrong way will eliminate the error. –- Dunlap, 1932: 95–96

A small study by Holsopple and Vanouse (1929) tested the beta hypothesis with eleven shorthand students. They were asked to employ normal (“positive”) practice to counteract one set of errors, and negative practice to deal with another set. Negative practice was found considerably more effective with this group. In fact, all eleven students appeared to benefit, with errors for negatively practiced words being reduced to zero while mistakes were still being made with the positively practiced words about thirty percent of the time.

A few years later, two researchers published an article summarizing the findings of several additional experiments, from which they concluded:

These and other considerations arising from a more detailed analysis of the data tend strongly to support Dunlap’s beta hypothesis of negative practice. — Kellogg & White, 1935

The main recommendation emerging from early research reviews was that negative practice tends to work better when “massed” rather than “distributed”, i.e., when the behavior to be eliminated is practiced lots of times in rapid succession during each practice session.

How to do Negative PracticeIn a nutshell, Dunlap’s method involved asking subjects with stutters, tics, and other unwanted habits to voluntarily engage in the behavior over and over again with little or no delay between repetitions. Most importantly, though, they were to bear in mind their goal of breaking the habit. For example, before each negative practice session, clients wishing to overcome a stammer would say to themselves:

“I am going to stammer; I am going to perfect my stammering (i.e., make it as near as possible like my usual stammering). I am to do this now, when I want to, because so doing will make it possible later for me not to stammer when I don’t want to. The better I stammer now, the sooner I will break the habit of stammering.” — Dunlap, 1932: 205

Dunlap found that behavior could be changed in this way, though it sometimes required as much as two fifteen-minute sessions of daily practice for 3–4 weeks.

Negative practice is so-called because it involves practicing a habit you want to unlearn or negate. Later authors refer to a variety of similar techniques as “paradoxical” therapy — the paradox being that you’re instructed to do more of something you want to stop doing. It’s also sometimes referred to as “symptom prescription”.

The behavioral psychologist Clark Hull argued that negative practice might work through a neurological process he called “reactive inhibition”. According to this theory when some piece of behavior is repeated many times in rapid succession your nervous system automatically begins to react by weakening and inhibiting the habit regardless of your intentions.

Other behaviorists observed that intensive sessions of negative practice can also lead to feelings of fatigue, self-consciousness, awkwardness or aversion, which might actually be helpful if they inhibit the unwanted habit. Although there are differing opinions about exactly how the technique works they’re not mutually exclusive — several of these things might be happening at once.

More Examples of Negative PracticeThe pioneering behavior therapist Andrew Salter adopted Dunlap’s negative practice technique in the 1940s, and gave this brief case-study of blushing as an example:

I explained to Mr. T. that the human nervous system had, as it were, a logical battery and an emotional battery. Both were connected by wires to different parts of the body. “Your emotional battery, through what is called the autonomic nervous system, sends messages unconsciously to the blood vessels in your face, making you blush. Now, if we can use some power from the logic department instead, you will develop a deliberate hold on the blood vessels, and overcome the unconscious blush signals. The logical department of the brain will tell your face, “You won’t have to blush.” So I want you to deliberately practice blushing. Tell yourself to blush at all times: when you’re alone, and when you’re with people. Get practice in sending logical electricity to your face instead of emotional electricity, and that will put logic in charge of blushing. When you control it, that will be the end of it.” I emphasized that he must practice this vigorously, and it was my impression that he would. When I saw him a week later, he was a bit perplexed. “You know,” he said, “I find that I can’t blush whether I want to or not. It’s the darndest thing.” — Salter, 1949: 64–65

Salter also provides a further example of the technique in which he prescribed that a pretty young lady who had a flatulence problem should, “practice the deliberate breaking of wind at all times.”

The existential psychotherapist Victor Frankl, author of the bestselling Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), likewise developed a technique he called “paradoxical intention”, which appears very similar to Dunlap’s negative practice.

It consists not only of a reversal of the patient’s attitude toward his phobia inasmuch as the usual avoidance response is replaced by an intentional effort — but also that it is carried out in as humorous a setting as possible. — Psychotherapy & Existentialism, 1967

Elsewhere Frankl provides a brief case study concerning a young doctor who had developed a phobia about sweating. One day, meeting his boss on the street, as he extended his hand in greeting, he noticed that he was sweating more than usual. Each time he then found himself in a similar situation he grew nervous, expecting that he would sweat profusely.

It was a vicious circle… We advised our patient, in the event that his anticipatory anxiety should recur, to resolve deliberately to show the people whom he confronted at the time just how much he could really sweat. A week later he returned to report that whenever he met anyone who triggered his anxiety, he said to himself, “I only sweated out a litre before, but now I’m going to pour out at least ten litres!” What was the result of this paradoxical resolution? After suffering from his phobia for four years, he was quickly able, after only one session, to free himself of it for good. — Psychotherapy & Existentialism, 1967, p 139

Although Frankl emphasized that humor was an important part of symptom prescription, researchers employing similar techniques haven’t always found this necessary.

Dunlap used negative practice as his main approach for a wide variety of problems, including behavioral habits like nail-biting, mental habits like worrying, and emotional habits like becoming angry with people. Over the years similar paradoxical techniques have been used to address an even wider range of problems. The treatment of insomnia is perhaps one of the most common uses of symptom prescription in behavior therapy. Paradoxically, clients often find that being told to “try to stay awake as long as possible” tends to make them fall asleep sooner.

Another technique that’s become increasingly common in modern cognitive-behavioral therapy involves the prescription of deliberate “worry time”. A client who feels immersed in their worries is advised to set aside, e.g., half an hour each day to sit in a specific chair and worry voluntarily. Worrying is postponed until then when they can focus more attention on the process. Of course, nobody “worries” deliberately, worries creep into our mind when not wanted. When we set about thinking our worries through deliberately they often seem ridiculous or trivial and the effort can become tedious after a while. This feeling of fatigue or boredom while engaged in the negative practice is perhaps useful, as mentioned earlier. It may actually contribute to the inhibition of the habit.

The English psychologist Edward B. Titchener was reputedly the first to observe, at the start of the 20th century, that when a word or short phrase is repeated aloud very rapidly for a period of time the speaker typically begins to experience it as meaningless gibberish. Recently this has become a common technique in a state-of-the-art form of cognitive-behavioral therapy known as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). For instance, suppose that you’re troubled by a distressing thought such “Everyone hates me!” Repeating that sentence aloud, as fast as you can, for at least a minute, will feel surprisingly difficult. Research shows that in about 90% of cases people who do this report that the phrase feels more empty or meaningless as a result, which can greatly diminish the thought’s ability to cause distress.

Conclusion: Some Practical TipsHere are some more practical tips derived from the clinical and research literature on negative practice:

You should have a moderate desire to eliminate the behavior you’re practicing and focus throughout the practice on the idea that you’re repeating the habit in order to rid yourself of it.

It often helps to bear in mind examples of how negative practice has been found effective in removing undesired habits such as in the training of typists.

You’ll need to address any underlying motives for clinging on to the habit, e.g., biting your fingernails as a way of distracting yourself from social anxiety.

You may need to have a new way of responding once the habit is gone, e.g., if you eliminate the habit of mispronouncing a word you’ll need to know the correct pronunciation to replace it.

It’s important to reproduce the habit that you’re trying to eliminate as accurately as possible and to repeat it for long enough that it starts to feel quite awkward or tedious.

It can also be useful to spot the bad habit whenever it happens spontaneously and straight away repeat it over and over again, voluntarily, as a form of negative practice. Of course, if you’re suffering from a severe problem you should seek assessment and treatment from a qualified professional. However, many everyday bad habits can be broken by using a variation of this simple technique. People often find it tremendously liberating to discover, after years of trying to force themselves to stop a bad habit, that an easier and more effective solution may be to actually do the very thing they’ve been trying so hard to avoid. As Blake also said, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

September 28, 2024

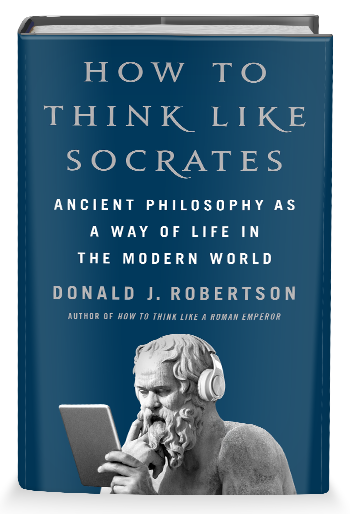

Win a free copy of "How to Think Like Socrates"

My publisher, St Martin’s Press, has generously offered to give away 25 copies of How to Think Like Socrates. Enter the Goodreads giveaway for a chance to win one!

This offer is open until Oct 24, 2024, to participants from the US and Canada only. (Stay tuned for international offers, as the book is released in other regions.)

A practical application of his philosophy to contemporary problems, this book makes the wisdom of Socrates more accessible than ever before. — Barnes & Noble

“One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! Highly recommended!”—Tom Morris, author of If Aristotle Ran General Motors

“Wonderful . . . In our modern world that swirls with half-truths and disinformation, we need nothing less to awaken us from our illusions.” —Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom

“An intriguing and original book, engagingly written and highly accessible.” —Chris Gill, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Thought, Exeter University, and author of Learning to Live Naturally

“A fresh and original introduction to the figure of Socrates, blending philosophy, history, and psychotherapy.”—John Sellars, reader in philosophy at Royal Holloway, University of London and author of The Pocket Stoic

“Don Robertson is your trusty and insightful guide to the life, times, and thought of the most important philosopher in the western tradition.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 24, 2024

Socrates Explains Your Cynicism

What can Socrates tell us about the root causes of cynicism, misogyny, misandry, and misanthropy, in modern society? It turns out, in typically Socratic fashion, that his answer is to highlight a paradox.

By cynicism with a small c (never capitalized) I mean the modern concept of a negative attitude concerning other people’s motives. A cynic assumes the worst about their fellow human beings and says things like “People are only out for themselves.” That’s not to be confused with Cynicism, which is usually capitalized to denote the ancient Greek philosophy exemplified by Diogenes of Sinope, and his followers. The Cynic philosophers definitely appear cynical at times but there was much more to their philosophy than this, and their goal was to flourish and help improve their fellow citizens, not simply to complain about them.

Timon of Athens, the classic misanthrope

Timon of Athens, the classic misanthropeIn one of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates briefly discusses the concept of misanthropy, a deep-seated distrust and even hatred of other humans. Misanthropy is like cynicism and some. Misanthropes don’t just distrust other people, they actively detest them. We can view misogyny, or hating women, and misandry, or hating men, as specialized forms of misanthropy, worth mentioning because arguably they’re more common, and more prominent, today than the more general attitude of simply detesting everyone.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Phaedo depicts Socrates’ final hours in prison, before his execution. He contentedly discussed philosophy with a group of friends, focusing on questions about the nature of the soul and its fate after death.

At one point, however, Socrates tells Phaedo that if they wish to continue their discussion they must be on their guard against a danger. Phaedo is puzzled and asks him what he means.

The danger of becoming misologists or haters of reason, as people become misanthropists or haters of man. For no worse evil can happen to a man than to hate reason.

A misologist is someone who hates reason or rational argument, and by implication, philosophy.

Socrates is serious. He believes that there are many people who exhibit an aversion to logic or reason, and that this is among the worst afflictions that can befall us. For our purposes, though, it’s interesting to note that he considers this problem to originate in more or less the same way as misanthropy.

Misology and misanthropy arise from similar causes. For misanthropy arises from trusting someone implicitly without sufficient knowledge. You think the man is perfectly true and sound and trustworthy, and afterwards you find him base and false. Then you have the same experience with another person. By the time this has happened to a man a good many times, especially if it happens among those whom he might regard as his nearest and dearest friends, he ends by being in continual quarrels and by hating everybody and thinking there is nothing sound in anyone at all.

Ironically, then, we become cynical because we trust other people too much.

Socrates believes that our cynicism is spawned by our own misplaced trust and gullibility. When we naively place too much faith in the wrong people, we are bound to be let down by them eventually. If this happens repeatedly, and with people we care about, then we end up feeling that we can no longer trust anyone, and are left permanently bitter and cynical.

It’s even easier to see this if we narrow our focus and look at the example of misogyny. Suppose a young man falls in love with a woman, loses perspective, and falls into the trap of viewing her in a naive and idealistic way. If he falls for the wrong woman, she’s likely to end up rejecting, betraying, or otherwise disappointing him. If his feelings are hurt too often or too catastrophically, he may become bitter and cynical. In order to protect himself from making the same mistake again, and naively trusting the wrong woman, he will now tell himself that all women are untrustworthy.

This can happen to anyone, if they trust blindly in the wrong individual. It’s more often young people who react so strongly to rejection, because they have less experience to draw upon, in order to maintain perspective. Depending on whether your heart has been broken by a woman or a man, you may end up trying to protect your self-esteem by becoming either a misogynist or a misandrist — a pathological women-hater or man-hater.

Socrates goes on to explain that someone is only vulnerable to this sort of cynicism, if they lack a basic understanding of human nature.

Well, is it not disgraceful, and is it not plain that such a man undertakes to consort with men when he has no knowledge of human nature? For if he had knowledge when he dealt with them, he would think that the good and the bad are both very few and those between the two are very many, for that is the case.

Socrates thinks this is shameful because it is obviously quite childish. Children tend to think in more black-and-white terms than adults. As our thinking matures, we become more capable of fine distinctions.

When someone lacks a mature and balanced understanding of human nature they will tend to either idealize or demonize other people. They naively invest their trust in someone, idealizing them at first, only to discover that they are not perfect, at which point they may feel hurt and demonize them. They go from one extreme to the other. And if this happens too disastrously or too frequently, they may end up, misanthropically, demonizing everyone they meet. They think, perhaps without even realizing that it is what they think: that if they never trust anyone again, they will never again be disappointed.

Socrates notes that “big” and “small” are relative terms, and that, almost by definition, it is unusual to meet a very big person or a very small one, as most people are medium sized. In the same way, we should realize that it is unusual to meet a very good person or a very bad one, and that most people are in between, and capable of doing both good and bad things. A wise person, therefore, realizes that most people cannot be trusted unconditionally, at all times, and to assume otherwise would be childish and naive.

Socrates concludes by returning to his analogy, and explaining that misology, a pathological distrust of reason, can originate from gullibility in much the same that misanthropy does.

When a man without proper knowledge concerning arguments has confidence in the truth of an argument and afterwards thinks that it is false, whether it really is so or not, and this happens again and again; then you know, those men especially who have spent their time in disputation come to believe that they are the wisest of men and that they alone have discovered that there is nothing sound or sure in anything, whether argument or anything else, but all things go up and down, like the tide in the Euripus, and nothing is stable for any length of time.

In other words, people who are gullible and too easily persuaded by weak arguments, will usually end up disappointed when they discover, later, that they have been misled. If this happens repeatedly, they will end up feeling as though nothing is true, and that anything goes. Ironically, that makes them assume that they are wise and others are foolish, when, in fact, they have merely replaced philosophy, and the pursuit of wisdom, with cynicism.

ConclusionIt’s not clear who the misologists are, although it seems likely that Socrates may have had certain Sophists in mind. The first famous Sophist was Protagoras, who was known as the wisest man alive among his followers. Plato portrays him as a relativist, who doubts whether anything can be absolutely or objectively true. Protagoras and the Sophists who followed in his footsteps were more interested in using rhetoric to win arguments than in employing reason to arrive at the truth. Their wisdom, therefore, was all about appearance.

In modern society, it’s often been observed that many of those drawn to philosophy, looking for some sense of direction, are young men. In some cases, they seem to be turning to philosophy, looking for direction, and seeking a substitute for a father figure. They often feel very angry, disillusioned and cynical about the world. Sometimes they are preyed upon by “self-improvement” influencers, in the so-called manosphere, who exploit their sense of vulnerability concerning their masculinity in order to make money from them. (Andrew Tate, for instance, who has referred to himself as a “misogynist”, something in which he appears to revel.) Exactly the same thing used to happen in ancient Greece, and Socrates often warned young men to be on their guard against those who would take advantage of them in this way.

Cynicism and misanthropy are, basically, forms of anger. Clinical research on the psychology of anger has shown that in the vast majority of cases people become angry in response to initial feelings of hurt or anxiety. We usually get angry in order to conceal our pain and defend ourselves against having our feelings hurt again. The misogyny of these angry and desperate young men is perhaps a direct result, ironically, of their childishness and naivete with regard to women. They invest too much, emotionally, in the wrong people, and set themselves up for failure, and disillusionment. Indeed, by embracing misogyny and casting their lot in with gurus from the manosphere, they appear to be simply replacing their failed idealization of women with the irrational idealization of another male. That too may be doomed to end in disappointment, leading to yet more bitterness and cynicism.

Cynicism, misanthropy, misogyny, misandry, etc, offer us protection. If we never trust anyone again, we’ll never be disappointed by anyone again. Or at least, that’s what we assume. In reality, we make ourselves even more vulnerable by embracing this kind of pervasive negativity. Anger excels at achieving the opposite of what it desires. Angry people want others to respect them, but ultimately they alienate everyone, and destroy any hope of finding fulfilment in a lasting relationship. Marcus Aurelius said that, ironically, our own anger harms us more than the things about which we’re angry. Cynicism, likewise, does you more harm than the things about which you are cynical.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 23, 2024

The Stoicism of Augustus

’Tis glorious to tower aloft amongst great men, to have care for fatherland, to spare the downtrodden, to abstain from cruel bloodshed, to be slow to wrath, give quiet to the world, peace to one’s time. This is virtue’s crown, by this way is heaven sought. So did that first Augustus, his country’s father, gain the stars, and is worshipped in the temples as a god. — Pseudo-Seneca, Octavia

The most famous Stoic philosopher is, without doubt, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Countless people have read his book The Meditations since the first English translation appeared in the early 17th century. Many moviegoers also became familiar with Marcus from Richard Harris’ portrayal of him in the Hollywood sword-and-sandals epic Gladiator (2000). However, it’s less well-known that, over a century before Marcus was born, the first Roman emperor was also a student of Stoicism and the author of an essay praising philosophy.

The man we call Augustus (63 BC — 14 AD) was the founder of the Roman empire. Early in his life he was known as Octavian, the grand-nephew of the dictator Julius Caesar. Lacking any legitimate offspring, Caesar adopted Octavian and named him his heir. Following Caesar’s assassination on the Ides of March 44 BC, Rome went through a long period of political instability which culminated in the naval Battle of Actium (30 BC). The fleet of Octavian defeated the combined forces of Mark Antony and his lover, Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt. Octavian was left the sole ruler of Rome and gradually accumulated more and more powers. In 27 BC, the senate granted him the titles Augustus and Princeps, or first citizen, effectively becoming emperor and defining the role that would be occupied by his successors for centuries to come.

Augustus was certainly never remembered as a Stoic philosopher in the sense that Marcus Aurelius was. However, the historian Suetonius claims in Lives of the Caesars that Augustus was the author of numerous writings including a lost work titled Exhortations to Philosophy. We’re told that late in life Augustus would read these to a group of his intimate friends, as though delivering a class in a lecture room. Suetonius also mentions a text by Augustus called “Reply to Brutus on Cato”. We can probably assume this was a response to Brutus’ eulogy for his uncle, the famous Republican Stoic, Cato of Utica. Brutus, one of the main assassins of Augustus’ adoptive father, Julius Caesar, was also reputedly a student of Stoicism.

So, in addition to Augustus’ Exhortations to Philosophy, his Reply to Brutus on Cato may have touched on philosophical themes, as may his other lost writings. These claims become more plausible when we learn that, earlier in his life, Augustus had two Stoic tutors.

Athenodorus Canaanites & Arius DidymusAthenodorus Canaanites, from Canaana near Tarsus, a student of Posidonius of Rhodes, was Octavian’s first Stoic tutor. He began teaching the young man in the city of Apollonia, Illyria (modern day Albania), and later followed Octavian on his return to Rome in 44 BC, aged 19. Athenodorus reputedly wrote a lost work dedicated to the elder sister of Octavian, Octavia Minor.

Octavian’s other, and probably slightly later, Stoic tutor was Arius Didymus of Alexandria. Arius was the author of an important summary of early Stoic teachings, long fragments of which survive today in the anthologies of the doxographer Stobaeus. Seneca says, in On Clemency, that although Augustus naturally had a temper, and executed many enemies earlier in his life, he changed completely later in his reign. Around 16 BC a man called Gnaeus Cornelius Cinna Magnus was caught plotting to assassinate Augustus. Following the advice of his wife, Livia, Augustus decided that he could no longer continue executing his enemies, and adopted a policy of clemency toward Cinna, after which plots against him apparently ceased. Arius was an expert on Stoic psychotherapy, and later, around 9 BC, wrote a highly-regarded consolation letter to Livia, the wife if Augustus, containing Stoic psychological advice to help her cope emotionally with the loss of her beloved son, Drusus. The philosophy’s value in consoling his wife, Livia, appears to have strengthened Augustus’ association with Stoicism.

Suetonius, the historian, said that Augustus had at first been interested in studying Greek literature. He trained in Greek rhetoric, although he never mastered the language, but later became more interested in philosophy, particularly Stoicism.

Later he became versed in various forms of learning through association with the [Stoic] philosopher Areus [Didymus] and his sons Dionysius and Nicanor. — Suetonius, The Lives of Caesars

We’re told that in reading both Greek and Latin, “there was nothing for which he looked so carefully as precepts and examples instructive to the public or to individuals”. He would copy these down verbatim and send them to members of his household, generals and provincial governors, who might especially benefit from them. Suetonius says Augustus even recited “entire volumes” to the senate and called the attention of the public to them through proclamations, including a speech by Publius Rutilius Rufus, another Stoic, titled “On the Height of Buildings”.

Although more of Arius’ writings survive, in this article I’m going to focus on Athenodorus and his possible influence upon Octavian. For example, in his Moralia, Plutarch recounts the following anecdote:

Athenodorus, the philosopher, because of his advanced years begged to be dismissed and allowed to go home [presumably from Rome to Tarsus], and Augustus granted his request. But when Athenodorus, as he was taking leave of him, said, “Whenever you get angry, Caesar, do not say or do anything before repeating to yourself the twenty-four letters of the alphabet,” Augustus seized his hand and said, “I still have need of your presence here,” and detained him a whole year, saying, “No risk attends the reward that silence brings.” — Plutarch, Moralia, Sayings of Romans: Caesar Augustus

This strategy of taking what modern therapists would call a “time-out” before acting on feelings of anger was fairly well-known in the ancient world. However, Athenodorus gives a very clear example of how this was to be accomplished in practice by pausing to recite the Greek alphabet. Perhaps it worked, as Seneca refers to Augustus as an example of someone who ruled without anger.

The late Emperor Augustus also did and said many memorable things, which prove that he was not under the dominion of anger. — Seneca, On Anger, 3.23

Seneca goes on to explain that Augustus was satisfied to leave the company of critics, without feeling the need to take revenge on them.

Let everyone, then, say to himself, whenever he is provoked […] Have I more authority in my own house than the Emperor Augustus possessed throughout the world? Yet he was satisfied with leaving the society of his maligner. — Seneca, On Anger, 3.24

In his earlier years, Octavian is believed to have had quite a violent temper but perhaps Seneca means to suggest that later in life, as Augustus, he overcome this tendency, perhaps in part as a consequence of his training in Stoicism.

There were several philosophers called Athenodorus but it seems likely Seneca again means the tutor of Octavian when he mentions with approval a saying from Athenodorus: “Know that you are freed from all desires when you have reached such a point that you pray to God for nothing except what you can pray for openly” (Letters, 10). In other words, our deepest desires should be such as we would be unashamed to admit in public — a typical Cynic-Stoic theme that recurs in the writings of Marcus Aurelius.

Elsewhere Seneca also writes that Athenodorus said “he would not so much as dine with a man who would not be grateful to him for doing so” (On Tranquillity, 7). Seneca says he takes this to mean that Athenodorus would not eat with men who lay on banquets as a way of repaying their friends for their services because in doing so they rate their own generosity, with food and drink, too highly compared with friendship.

The Exhortations to PhilosophyThese sayings of Athenodorus are interesting. However, Seneca also quotes a lengthy excerpt from his writings, which seems especially relevant. It’s explicitly addressed to young Roman men who are considering a life in public office, just like Octavian was when he first met Athenodorus.

It argues that although their desire to benefit society is a noble one, political office is inherently corrupting. It advises them to remain in private life and focus on improving their own character first and foremost. They can more safely benefit society by providing a living example of wisdom and virtue than by trying to exercise political influence over others. In other words, what Seneca quotes at length from Athenodorus is a typical example of an exhortation, a genre also known as philosophical protreptic.

Although Augustus’ Exhortations to Philosophy has long been lost, we know his tutor Athenodorus’ exhortation reads like this…

The best thing is to occupy oneself with business, with the management of affairs of state and the duties of a citizen: for as some pass the day in exercising themselves in the sun and in taking care of their bodily health, and athletes find it most useful to spend the greater part of their time in feeding up the muscles and strength to whose cultivation they have devoted their lives; so too for you who are training your mind to take part in the struggles of political life, it is far more honourable to be thus at work than to be idle. He whose object is to be of service to his countrymen and to all mortals, exercises himself and does good at the same time when he is engrossed in business and is working to the best of his ability both in the interests of the public and of private men.

As noted above, these are words of advice explicitly aimed at Roman youths training themselves for future political careers, possibly including the young Octavian. However, Athenodorus continues,

But because innocence is hardly safe among such furious ambitions and so many men who turn one aside from the right path, and it is always sure to meet with more hindrance than help, we ought to withdraw ourselves from the forum and from public life, and a great mind even in a private station can find room wherein to expand freely. Confinement in dens restrains the springs of lions and wild creatures, but this does not apply to human beings, who often effect the most important works in retirement. Let a man, however, withdraw himself only in such a fashion that wherever he spends his leisure his wish may still be to benefit individual men and mankind alike, both with his intellect, his voice, and his advice.

Although, in a sense, the highest calling in life involves a commitment to the welfare of society, nevertheless public office can have a corrupting influence. So one is best advised to avoid a career in politics and retire instead to private life, where wise counsel can still be given from the sidelines. We should not live like hermits, however, but as philosophers, scholars, and teachers, who share their wisdom with others and provide them with role models.

The man that does good service to the state is not only he who brings forward candidates for public office, defends accused persons, and gives his vote on questions of peace and war, but he who encourages young men in well-doing, who supplies the present dearth of good teachers by instilling into their minds the principles of virtue, who seizes and holds back those who are rushing wildly in pursuit of riches and luxury, and, if he does nothing else, at least checks their course — such a man does service to the public though in a private station.

He goes on to ask whether one does more good for society as a magistrate, whether dealing with international or domestic cases (praetor peregrinus or praetor urbanus), or as one who can show people through his own example “what is meant by justice, filial feeling, endurance, courage, contempt of death and knowledge of the gods, and how much a man is helped by a good conscience”. It is better to be a wise and virtuous role model, Athenodorus is saying, and provide an example through your own character and way of life than to exert influence over society through public office.

If then you transfer to philosophy the time which you take away from the public service, you will not be a deserter or have refused to perform your proper task. A soldier is not merely one who stands in the ranks and defends the right or the left wing of the army, but he also who guards the gates — a service which, though less dangerous, is no sinecure — who keeps watch, and takes charge of the arsenal: though all these are bloodless duties, yet they count as military service.

By now, it’s clear that Athenodorus is writing an exhortation, encouraging his young readers to embrace the life of a philosopher.

As soon as you have devoted yourself to philosophy, you will have overcome all disgust at life. You will not wish for darkness because you are weary of the light, nor will you be a trouble to yourself and useless to others. You will acquire many friends, and all the best men will be attracted towards you, for virtue, in however obscure a position, cannot be hidden, but gives signs of its presence. Anyone who is worthy will trace it out by its footsteps.

He’s saying that a Roman youth can choose a private life of wisdom and virtue, through training in philosophy, and others will still seek him out because of his character and reputation. Stoic philosophers continue to dedicate themselves to the common welfare of mankind but they do so by sharing learning rather than engaging in lawmaking or politics. However, there’s another sort of retirement from public life, which is just vice and idleness, because it lacks any concern for the welfare of others.

But if we give up all society, turn our backs upon the whole human race, and live communing with ourselves alone, this solitude without any interesting occupation will lead to a want of something to do. We shall begin to build up and to pull down, to dam out the sea, to cause waters to flow through natural obstacles, and generally to make a bad disposal of the time which Nature has given us to spend. Some of us use it grudgingly, others wastefully. Some of us spend it so that we can show a profit and loss account, others so that they have no assets remaining: something than which nothing can be more shameful. Often a man who is very old in years has nothing beyond his age by which he can prove that he has lived a long time. — Athenodorus quoted in Seneca, On Tranquility, 3

The Stoics firmly believed in the brotherhood of all mankind. One of the cardinal virtues of their philosophy is justice (dikaiosune), consisting of both fairness and benevolence toward others. As Marcus Aurelius would later put it, to turn our backs on others is to be alienated from Nature as a whole, a form of injustice and impiety.

ConclusionIf I remember, then, that I am a part of such a whole, I shall be well contented with all that comes to pass; and in so far as I am bound by a tie of kinship to other parts of the same nature as myself I shall never act against the common interest, but rather, I shall take proper account of my fellows, and direct every impulse to the common benefit and turn it away from anything that runs counter to that benefit. And when this is duly accomplished, my life must necessarily follow a happy course, just as you would observe that any citizen’s life proceeds happily on its course when he makes his way through it performing actions which benefit his fellow citizens and he welcomes whatever his city assigns to him. — Meditations, 10.6

It’s hard to say how much the young Octavian’s Stoic tutors influenced his developing character and later career as Augustus. There are some tantalizing details, though. We’re told by he author Lucian that Augustus’ stepson and successor, the Emperor Tiberius, also studied Stoicism, under an otherwise unknown tutor called Nestor. Perhaps Augustus merely dabbled in Stoicism but set a precedent, planting seeds in imperial Roman society that would only grow to maturity, over a hundred years later, with Marcus Aurelius.

There are obvious differences. Augustus was at times perhaps a more politically opportunistic and violent ruler than Marcus. He was also curiously vain by comparison. Augustus notoriously insisted that all depictions of him should show him in the prime of life. Not a single statue exists today showing what he actually looked like later in life, although he lived to seventy-five — a grand old age by Roman standards. In sharp contrast, several statues of Marcus Aurelius, apparently in his late fifties, survive to this day, some of which look frankly haggard.

Marcus mentions the first Augustus three times in The Meditations. (The names of Roman nobles can be confusing: later emperors including Marcus also bore the name Augustus.) He says that everyday words from the past now have an archaic ring to them, as do the names of famous men such as Augustus. The founder of the empire was once flesh and blood but now he’s remembered by statues and stories in history books. Marcus notes that he has watched this happen, in his own lifetime, with the emperors Hadrian and, his adoptive father, Antoninus Pius (4.33). He knew them as real people but by the time he’s writing The Meditations, they’re already beginning to be seen as merely names in history books.

Elsewhere, Marcus reminds himself that even his most illustrious predecessors are now gone, returned to dust, and that this is his own fate, despite the supreme position granted to him.

First of all, be untroubled in your mind; for all things come about as universal nature would have them, and in a short while you will be no one and nowhere, as are Hadrian and Augustus. — Meditations, 8.5

Finally, Marcus once again uses Augustus, and the image of his entire court, to contemplate the transience of power, fame, human life, and indeed all material things.

Speak both in the senate and to anyone whatever in a decorous manner, without affectation. Use words that have nothing false in them. The court of Augustus, his wife and daughter, his descendants and forebears, his sister, and Agrippa [his general], his relatives, associates and friends, Areius [Didymus], Maecenas [his friend and political advisor], his doctors, his sacrificial priests — an entire court, all of it dead. — Meditations, 8.30-31

As it happens, in this passage, Marcus also mentions Arius Didymus, one of the Stoic tutors of Augustus, whom we met earlier. Marcus reminds himself that even the Stoic philosophers who taught the first Augustus, are long dead and gone.

September 21, 2024

Signed Copies of How to Think Like Socrates

When people ask me how they can get a signed copy of my new book, I finally have the answer!

The good people at Porchlight books, however, have arranged to accept preorders for signed copies of How to Think Like Socrates to your address, which can be shipped anywhere in the world. Porchlight are currently offering these at a discounted price — check the listing for more details.

If you do want a signed copy, this is the way to do it. (If you preorder my books, it helps a lot because it tells retailers there’s demand, and they’re more likely to feature them and help promote them.)

I used to sign copies in an independent bookstore in Toronto, who would take orders and ship them overseas, but, unfortunately, they closed following the pandemic. So it’s taken me a little while to find a viable alternative, now that I live in Quebec.

Unfortunately, these can’t be personalized, as I have to hand sign bookplates in bulk and mail them to the US warehouse that ships the orders. However, you’ll be able to place an order now and receive a signed copy as soon as the book is published.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 18, 2024

Join Me for a Conversation on the Power of the Socratic Method

I am pleased to share a recent conversation with Michael Balchan, President and Head Coach at Heroic. We explored the enduring relevance of the Socratic method together and its application to modern life.

Below are some of the key themes we addressed:

The Power of the Socratic Method: How the Socratic method isn’t just for philosophers—it’s a powerful tool you can use to approach life with more curiosity, wisdom, and self-awareness.

What "Know Thyself" Really Means: The importance of truly knowing yourself, how it can lead to personal breakthroughs, and how that concept applies today.

Understanding Anger: The root causes of anger and how understanding these can lead to transformative personal growth and emotional mastery.

The Power of In-Person Training: I’m thrilled to be joining Heroic in Athens this November, where we’ll immerse ourselves in the rich history of Stoicism. It’s a unique opportunity to experience learning on-site and connect with others on a similar journey. (If you'd like to join us a few tickets are still available, learn more here.)

Heroic's Founder and CEO Brian Johnson has also created PhilosophersNotes on several of my books. Heroic is sharing the Notes from How to Think Like a Roman Emperor and The Philosophy of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, also available for you right here.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I think you’ll really enjoy this conversation.

Regards,

Donald Robertson

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 17, 2024

How to Stop Catastrophizing

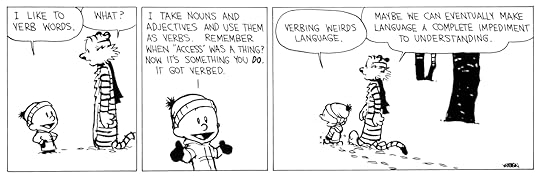

When we’re anxious, we tend to catastrophize. The term “catastrophizing” was coined in the 1950s by Albert Ellis, one of the pioneers of modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT). Ellis had been influenced by the linguistic concept of verbing or verbification, which refers to the act of turning a noun, such as catastrophe, into a verb, such as to catastrophize. By replacing the noun with a verb, we are encouraged to think of ourselves as engaged in an activity, and take more responsibility for the way we view things. Nothing in nature is a catastrophe. Humans choose to interpret certain events as catastrophic. Realizing when and how you’re catastrophizing is the first step to change.

Decatastrophizing is the name of a specific strategy used in cognitive therapy, of which there are several variations. Sometimes the term decatastrophizing is used more loosely simply to refer to the idea of countering catastrophic thinking. For example, catastrophizing is typically characterized by What if? thinking. “What if this happens? What if that happens? How will I cope?” Therapists often refer to the idea of replacing What if? thinking with So what? thinking. “So what if it does happen? It’s not the end of the world.” This technique of So what? thinking can be viewed as the simplest form of decatastrophizing.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In this article, I’ll look more closely at the nature of catastrophic thinking, before describing in detail how different versions of the decatastrophizing technique are used in cognitive therapy, and how they can be used for self-help. I’ll also be drawing some analogies with Stoic philosophy along the way.

Photo by Shannon Kunkle on UnsplashWhat is Catastrophic Thinking?

Photo by Shannon Kunkle on UnsplashWhat is Catastrophic Thinking?You may, perhaps as a child, have heard the tale of Chicken Little or Henny Penny. She was walking through the farmyard one day when something landed on her head — and it hurt! She flew into a state of high anxiety, and began to worry that the end of the world was nigh. Running around the farmyard, squawking “The sky is falling!”, she spread panic among the other animals. Eventually, a wise owl, the voice of reason, explained to everyone that it was merely a harmless acorn dropping from an oak tree that had hit Chicken Little on the head. With her catastrophic thinking dispelled, she returned to pecking corn peacefully in the yard. The moral is that once our anxiety is triggered we are all prone to take small threats and amplify them into ones that are much more severe and catastrophic.

Photo by Toni Cuenca on Unsplash

Photo by Toni Cuenca on UnsplashWhen we become anxious, our brain enters a different state, which cognitive psychologists call the “threat mode”. This is associated with a number of psychological and physiological changes, such as the fight-or-flight response, but also certain cognitive and attentional biases. We tend to pay more attention to potential signs of danger in our environment and to overlook signs of safety. One of the main problems with the threat mode comes from the way it causes us to engage in biased “threat appraisals”.

These appraisals can be broken down into three main elements:

Overestimating the probability of threat

Overestimating the severity of threat

Underestimating our ability to cope

In plain English, we tend to tell ourselves: Something awful is about to happen and I won’t be able to deal with it! Negative automatic thoughts of this kind are common in all forms of anxiety. When we dwell on these thoughts and ruminate about them, we experience a longer, and more voluntary, sequence of anxious thoughts known simply as worry.

Worrying tends to focus our attention exclusively on the worst-case scenario. Our thinking becomes extreme. We also tend to exhibit highly selective thinking, by ignoring evidence of safety, and what psychologists call “rescue factors”, such as resources available that might help us cope. We may jump to conclusions prematurely about what is bound to happen, which therapists sometimes call “fortune telling”. These are some of the most basic “cognitive distortions” or thinking errors found in anxiety and particularly in worried thinking.

Simply being more aware of catastrophizing as an activity, labelling it as a form of bias, or a thinking error, and taking more responsibility for doing it, can help us to break free from its grip. Often, near the start of therapy, clients will say “I noticed myself doing that ‘catastrophizing’ thing again but I was able to stop once I realized what was happening.” Often simple insights like this can be surprisingly powerful. Once we notice how we are deceiving ourselves, we are no longer deceived. The instant you truly realize that you are making an error in your thinking, you cease to make the error. As a result, you may have an Aha! moment and see through the illusion created by catastrophic thinking, almost as if you’re awakening from a trance.

Decatastrophizing in Cognitive Therapy

Decatastrophizing in Cognitive TherapyBeck and his colleagues have described their method of decatastrophizing in a number of different ways. It’s based on the premise that the situations we fear are, in reality, seldom as bad was we imagine when feeling anxious. It therefore requires facing your fears by confronting the idea or image of the worst-case scenario.

Normally people avoid really exposing their mind to their biggest fears in this way. You have to be prepared to endure what may be quite a challenging and uncomfortable experience. However, although your anxiety may increase at first, it will typically reduce during the exercise. By repeating this several times, perhaps once a day for five days or a week, you may find that the anxiety has been extinguished or at least reduced to a normal or negligible level.

The emphasis in this procedure is for the patient to see whether he can learn to accept and tolerate the experience he fears. The therapist stresses that the feared outcome is unlikely and that the patient still has some choice over how the situation turns out. — Beck et al., Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective (2005)

Don’t do this exercise alone if you suffer from a psychiatric condition, or if you experience panic attacks. In those cases, you’re probably better doing it under the supervision of a qualified mental health professional, simply because facing their worst fears can, despite the long-term benefits, be overwhelming in the short-term for some individuals, particularly those suffering from anxiety disorders.

For the majority of people, with less severe anxiety, though, facing the worst-case scenario will feel uncomfortable at first, as you’d expect, but it quickly becomes quite manageable. You could compare it to getting into a swimming pool filled with cold water, which may feel very bracing, like a shock to your system, but after a few minutes your body will get used to the temperature, until the water starts to feel quite normal and comfortable.

It’s therefore important to rate your level of anxiety before, during, and after each decatastrophizing exercise. Most people use a simple SUD (subjective units of discomfort) scale, from 0-10, although some people prefer to use a percentage. Measuring changes in your emotions actually makes them more likely to happen, and it also helps you to track your progress.

While avoidance may seem easy, and tempting, the more we try to suppress thoughts, especially those rooted in fear, the more persistent they become. Consider this example: try not to think about a polar bear for the next minute. The more we try to avoid thinking about anything, especially our fears, the more likely the thought is to keep recurring in the future. What if thinking about the worst could make it more likely to happen? That’s a common concern. However, clinicians have consistently found it disproven by experience. The mind doesn't manifest negative events simply by imagining them. Facing our fears, in the right way, usually makes them less powerful not more powerful.

Decatastrophizing ImagerySome people prepare themselves to do decatastrophizing by writing a catastrophizing script, describing in detail all of their worries about the worst-case scenario, which they fear. This can help you to visualize things but it’s not essential. The main step is simply to close your eyes and picture the worst-case scenario as if it’s happening right now. This is a form of what therapists call “imaginal exposure therapy”, which requires exposing your mind for a prolonged period to images that trigger anxiety. We know that doing this, very reliably, tends to lead to an initial increase in anxiety, followed by a reduction. Decatastrophizing differs from conventional imaginal exposure, however, because it also involves changing the way you think about the perceived threat, by challenging your catastrophic thinking.

As we’ve seen, simply realizing that you’re engaged in catastrophizing and labelling it as such is often enough to change how people feel. As we’ve seen, catastrophic thinking usually entails overestimating the probability of the threat. So Beck recommends that, if appropriate, you should focus your attention on the low probability of the worst-case scenario happening, while you mentally picture it. Consider the evidence for its likelihood, such as the fact that you have worried about many things in the past, and what percentage of them have happened as predicted.

Decatastrophizing involves the identification of the “worst-case scenario” associated with an anxious concern, the evaluation of the likelihood of this scenario, and then the construction of a more likely moderate distressing outcome. Problem solving is used to develop a plan for dealing with the more probable negative outcome. — Clark and Beck, Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders (2010)

I would say that, generally, however, I find it somewhat more helpful to focus on the other aspects of threat appraisal: the severity of the threat and your coping ability. This is where imagining the threat becomes more interesting. Picture the worst-case scenario in as much detail as possible, looking at it from different perspectives, patiently, maybe for 5-10 minutes, or longer. Explore the image by asking yourself questions such as: “What’s the worst that could realistically happen in this situation?”, “What’s so bad about that?”, “How might it affect your life?”, etc. By developing a more moderate and realistic appraisal of the threat’s severity, you will usually also arrive at a more likely perception of the outcome.

Ask yourself, therefore, whether your thinking about the severity of the situation is realistic or if it might contain any exaggeration or other thinking errors. Are things really as bad as you initially assumed? Knowing that the threat mode tends to narrow your attention onto signs of danger, causing selective thinking, try to reverse that by now paying more attention to any signs of safety or rescue factors. Look for evidence that things might not be as catastrophic as you at first imagined. Are there resources available or people who could help you survive?

Coping and Moving ForwardEven if the worst-case scenario happened, are there ways in which you could cope? What help or support is available in the situation? What resources could you use to get through it okay? What would you do if you were behaving more confidently or assertively in that situation? How might someone else cope with this problem?

When people worry, for some reason, their mind typically fixates on the worst moment in a sequence of events, the point at which their anxiety reaches its peak. In most cases, though, if you simply asked yourself what would probably happen next, and moved forward in time a little, you would eventually experience a sense of relief, and the image would feel less overwhelming. So deliberately get yourself past that stuck point. Ask yourself “what would most-likely happen next?, and after that?, and after that?”, and so on.

You can combine this with another technique called time projection, which involves asking yourself how you would feel about the feared event a week from now, a month from now, a year, a decade, and far away in the distant future. It might seem, at first, like an odd thing to ask but if you know that you would feel less upset about this event in the future, why shouldn’t you just choose to feel that way right now? (It can be useful just to contemplate that question for a while.)

After you’ve finished picturing the worst-case scenario and examining it patiently in your mind, asking yourself whether it’s really as bad as you initially felt, you may want to review the exercise by writing what’s sometimes called a decatastrophizing script. (If you earlier wrote a catastrophizing script, this would be the opposite, in a sense.) Write down a new description of the worst-case scenario, using completely objective language. Suspend any value judgements or emotive terminology. Just stick to the facts. Focus more than normal on any potential signs of safety or rescue factors, and conclude by describing in some detail how you would cope with the stress and problem-solve the external situation. Describing the worst-case scenario in this way should make it feel much less intimidating. When you then repeat the decatastrophizing imagery, you’ll find it much easier from now on to imagine events more realistically and without catastrophizing.

Some people also like to follow this by asking themselves what the best-case scenario would be. The most-likely case will usually be somewhere between the worst-case and the best-case scenario. Whenever you notice that you are worrying, catastrophizing, and focusing on the worst-case scenario, you can now deliberately shift your attention onto the most-likely scenario. In my view, though, if you adopt this strategy of shifting focus onto the most-likely scenario prematurely you risk turning it into a form of subtle (cognitive) avoidance. It’s better to wait until you’ve practised decatastrophizing in the image enough times for your anxiety to have reduced significantly.

Stoic DecatastrophizingThere are many ideas in the Stoic literature that could be linked to the concept of decatastrophizing.

Premeditation of AdversityThe Stoics advise us to go further than Beck, by imagining any misfortune that could conceivably happen, one at a time, as if it is happening now. The primary aim of Stoic premeditation appears to have been, in a word, to rehearse a philosophical attitude toward misfortune. However, the Stoics also seem to have understood the phenomenon of emotional habituation, i.e., that anxiety abates naturally through prolonged, repeated, exposure, such as imagining various misfortunes or worst-case scenarios for long enough. By targeting a range of adverse situations pre-emptively, Stoic premeditation appears designed to create general emotional resilience, and to function preventatively rather than therapeutically.

The Dichotomy of ControlThis is the opening sentence of Epictetus’ Handbook and the topic of the first book of the Discourses so it appears to be given a fundamental position in his approach to Stoicism. During premeditation or decatastrophizing, you can simply ask yourself which aspects of the situation are up to you and which are not. Another way of doing this is to ask yourself how much control you have over the outcome of the situation, roughly, from 0-100%. Assuming it’s not at either extreme, you can first ask yourself why you didn’t rate it 0% and then why you didn’t rate it 100%. This technique definitely seems helpful to people who are engaged in decatastrophizing. Dividing things into two columns seems to make it easier to parse difficult situations. All you have to do next is focus on accepting the aspects that you don’t control and taking more responsibility for the aspects that you do control.

Cognitive DistancingThe most well-known saying from Stoicism is the fifth passage of Epictetus’ Handbook, which reads “People are not disturbed by events but by their opinions about them.” Bearing this in mind while you’re examining the image during decatastrophizing can help you to gain what Beck called “cognitive distance”, by separating your thoughts from the situation to which they refer. Nowadays, we’d tend to view this as a form of mindfulness and acceptance practice in CBT and, indeed, you can approach decatastrophizing as an opportunity to exercise mindfulness while rehearsing the mental imagery. That alone will tend to reduce your anxiety as well as improving your ability to think through coping strategies.

Stoic Functional AnalysisWe could list many other Stoic techniques but the one I sometimes find most helpful, for want of a better name, I call Stoic “functional analysis.” In behaviour therapy, functional analysis is a process whereby we understand the purpose of a behaviour by identifying its antecedents and consequences. (For which we use the acronym ABC: antecedents, behaviour, consequences.) Most habits are triggered by certain antecedents and maintained, often in subtle ways, by its consequences, in the form of external punishments or rewards. For the Stoics this takes a slightly different form because their philosophy assumes that we should be more motivated by whether something helps or harms our own character. The way they would remind themselves of that perspective was by repeating the paradoxical saying that our own fear does us more harm than the things of which we are afraid.

Here are some variations of that you can try doing during decatastrophizing imagery:

“What does you more harm, the situation you worry about or your worry itself?”

“What does you more harm, the worst-case scenario or your catastrophizing?”

“What does you more harm, the trigger event or your emotional response?”

These are all questions designed to shift your focus away from perceived threats and back on to your way of thinking and responding to the situation. You will find that by asking these questions, with mindfulness and self-awareness, you are able to gain further cognitive distance in the situation.

ConclusionIf you understand the concept of catastrophizing and can spot yourself doing it, you will already be able to gain cognitive distance, and by facing your fears in imagination, patiently, and repeatedly, you can learn to turn a perceived catastrophe into a more tolerable experience, from which you can potentially learn. To recap, apart from just getting used to the feared situation, decatastrophizing also works by encouraging us to view the worst-case scenario more rationally and realistically, in a balanced way.

We begin to re-evaluate our appraisal of the probability of the threat, by becoming more aware of evidence suggesting the worst-case is quite unlikely

We begin to re-evaluate our appraisal of how severe the worst-case would be — is it really the end of the world?

We become more aware of the whole situation, including signs of safety and rescue factors, which we’d previously overlooked, such as opportunities for help and other resources

We begin to problem-solve and identify practical solutions, which we can rehearse in our mind’s eye until we feel more confident about coping

We move past fixation on the worst moment and begin to imagine what would happen next, viewing events from a broader chronological context

Remember, as Seneca once said, "We suffer more often in imagination than in reality", because there are far more things in life that are capable of frightening us than there are which can actually destroy us.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 16, 2024

Testing Stoic Anger-Management Technique #1

Every so often I like to ask people to provide feedback on a psychological technique. At the moment, I’m doing research for a book on the philosophy and psychology of anger, so I’ve been writing about various anger management strategies. The technique below is extremely simple, and virtually lifted straight out of the ancient Stoic literature. My experience has been that clients in therapy and coaching have found it helpful, and I believe it may have potential as an adjunct to cognitive psychotherapy for anger.

If you want to give it a try, just click the button below or follow this link to complete the online exercise. It only takes a few minutes.

Gathering your self-ratings and other feedback helps us to refine these techniques. This isn’t, of course, intended to be a controlled research study. However, simple feedback questions like the ones in this form can help refine protocols which could be tested more formally at a future date.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I’ve deliberately given minimal instructions in the online form because I want to know how people respond to the bare-bones technique, what problems they encounter, if any, and what questions they have. In reality, a technique like this would normally be delivered as one component of a more complex cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) treatment plan for anger, along with a lot more assessment and information about the problem and a variety of treatment strategies. So don’t worry too much if it seems like a fragment of something bigger, because that’s the idea.

Photo by Lewis Roberts on UnsplashTips and Advice

Photo by Lewis Roberts on UnsplashTips and AdviceI'll just a couple of brief points in response to some of the questions we’ve had so far. Several people asked how this could be applied to real world (in vivo) situations as well as the imaginal (in vitro) situation, a memory, which we used for the exercise script. The short answer is that, with repetition, emotional changes experienced in response to mental images tend to transfer to real world situations, and there are other strategies that can be used to facilitate this. Moreover, for many people, anger in response to memories is a major component of their problems. We chose a memory for this exercise because it’s much easier for most people to do that sort of test.

Some people said it can be challenging to focus attention on a question of this kind while experiencing anger in a real situation. That’s to be expected but the difficulty here may actually be a an integral part of the exercise. For instance, it requires significant effort to do sit ups with a weight on your chest but that’s precisely why it’s beneficial. So don’t worry if it feels hard at first to focus your attention continually on the question assigned in the exercise. Think of yourself as exercising your brain, your mental muscle, in the same way that you might do physical exercises to strengthen the muscles of your body. You’ll definitely find it easier with practice.

Likewise, you’ll notice that here we’re only asking you to do the exercise once — the bare minimum. In reality, you’d normally repeat an exercise like this at least three times, perhaps more, or just continue doing it for longer, maybe another five minutes, in one session. You’d also typically expect to repeat those sessions about once per day, for roughly 5-10 days. With more repetition, you’d expect to observe more benefit, but here we’re just interested in getting feedback on a single repetition of a few minutes’ duration. Of course, there’s nothing to prevent you from using the technique more extensively afterwards, if you choose to do so.

There are definitely other techniques, which we would expect to enhance the effects of the one described in the online form above. We’re isolating it here, though, because we want to ensure we’re getting feedback on this technique alone, and not mixing it up too much with other techniques that could affect the outcome. Although, under normal circumstances, of course, we’d want to do combine techniques that enhance each other when used together.

If you want a more comprehensive overview of anger management strategies from CBT, check out my pretty detailed article below.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 13, 2024

What can Stoicism teach us about anger?

I’m doing some research for a book about anger, and would value your input. What concepts or practices do you think we can learn from Stoic philosophy that might help us deal with our own anger and that of others? Let’s start a discussion! Everyone is welcome to join in. Please comment.

Photo by Caz Hayek on Unsplash

Photo by Caz Hayek on Unsplash

September 10, 2024

Some Anger-Management Strategies

All of these techniques are used in cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), although different practitioners tend to combine them in different ways. Our main source for concepts and terminology used below will be the works of Aaron T. Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Core StrategiesSelf-MonitoringSelf-monitoring is an important part of most CBT. In many cases, though, it’s not just about gathering information. In my view, it’s better to think of self-monitoring as cognitive skill, i.e., a form of “mindfulness” or self-awareness training. That’s because self-monitoring alone can often lead to self-improvement, perhaps through a “measurement effect” of sorts. One reason for this is that self-observation tends to interfere with the automaticity of habits, including the sequence of thoughts and actions that occur during anger.

The simplest form of self-monitoring is to keep a tally or count of how many times each day you notice yourself getting angry – tracking the frequency in this way is usually how I advise clients to begin self-monitoring. For example, you might simply note down that you became angry once on Sunday, three times on Monday, and twice on Friday.

The next step could involve recording the frequency, intensity, and duration of your anger episodes (e.g., 'Angry twice on Wednesday - once for 5 minutes at 5/10 intensity, and once for an hour at 4/10 intensity'). Timing episodes last can help reduce their duration, which often also leads to a decrease in their frequency and intensity.

A more advanced approach, although commonly used in CBT, is called the daily thought record. This can take different forms but, e.g., a simple version might include recording where and when an episode of anger occurred, and your thoughts, actions, and feelings in response to it.

Situation | Automatic Thoughts | Feelings | Behaviour

Briefly describe the situation, including the date and time. Note especially any negative automatic thoughts that popped into your mind between the triggering event occurring and your emotional reaction appearing. Describe your emotions briefly (rating the intensity from 0-10), and note any physical sensations accompanying them, and also note what you said or did. Below, I’ll describe how cognitive therapy disputes negative automatic thoughts. This form can be adapted to include thinking errors you identify in your negative automatic thoughts, and evidence for and against them, which turns it into more of an exercise in cognitive disputation instead of simple self-monitoring.

Photo by Daniel Lincoln on UnsplashSpotting Early-Warning Signs

Photo by Daniel Lincoln on UnsplashSpotting Early-Warning SignsI normally recommend that all clients do this early on, when working on anger. People tend to report feeling that they have more control earlier in episodes of strong emotions such as anger and that as it escalates they feel less in control. If you can notice what previously went unnoticed, especially the “early-warning signs” of anger, you will be more able to “nip it in the bud” before it escalates. Writing things down tends to heighten attention, so making a list of the early warning signs that you notice can actually change how you feel during an episode of anger. You have to first notice that you’re becoming angry before you will be able to apply any other techniques in the situation. However, becoming more aware of what’s happening earlier in the process will often be sufficient to break the cycle.

Early-warning signs might include certain images, automatic thoughts, or bodily sensations, but in practice it’s very common for people to begin noticing areas of muscular tension, or physical behaviours, that they’d previously overlooked. A coach or therapist can help you do this by asking questions. For instance, it’s common for angry people to frown, clench their jaw, tense their shoulders, or make their hands into fists. They’re often unaware, at the time, though, that they’re doing these things because they’re so absorbed in thoughts about the situation that is making them angry. Reversing that by increasing awareness of your own activity in the present moment is therefore likely to derail your anger, and increase your sense of control over your response to the situation. Charles Darwin famously observed that some of our emotional expressions are inherited from animals, such as furrowing our brow when worried or angry.

Taking a Time-OutOne of the simplest and most powerful tools for managing anger comes simply from learning to view anger as a different “mode” of psychological functioning from your normal brain state, not unlike the way we think of someone who is intoxicated or very tired or anxious as temporarily “not themselves” or “not thinking clearly”. Anger introduces some well-documented biases and limitations, which impair our ability to solve complex problems, especially social ones. Once we know that, though, if we notice ourselves entering what Beck calls the “hostile mode”, we can treat it as a signal to take a “time out” from the situation, and postpone our attempts to tackle any problems. Wait until you’ve calmed down and are thinking more clearly before planning how to respond to the situation, or engaging in problem-solving.

Automatic versus Voluntary ThoughtsWhy do people find it so difficult to deal with anger and other unruly emotions? One of the reasons is that most of us don’t distinguish clearly enough between our automatic and voluntary mental activity. Automatic thoughts are ideas or images that just pop into your mind unbidden, perhaps triggered by something you hear or so, or just seemingly out of nowhere. They are usually fast, sometimes barely conscious, and typically stand-alone at first rather than part of a logical sequence of reasoning. Voluntary thinking tends to be slower, more conscious, and consists more of an ongoing internal conversation, or line of reasoning.