Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 10

December 12, 2024

Every day imagine death and other misfortunes...

CommentaryKeep before your eyes day by day death and exile, and everything that seems terrible, but most of all death; and then you will never have any abject thought, nor will you yearn for anything beyond measure.

This seems to be a clear reference to the famous Stoic practice, which Seneca called praemeditatio malorum, in Latin, or the premeditation of adversity. In Greek, this was apparently called proendemein, which basically means “dwelling on something in advance”. Epictetus clearly recommended this to students as a daily Stoic contemplative practice. We’re regularly to picture things like death, exile, and anything that we consider catastrophic, but especially our own death.

December 11, 2024

Have you thought about giving an audiobook as a last-minute present?

You can now send the audiobook of How to Think Like Socrates to someone as a Christmas present via Audible. This can be done either by printing gift card or by scheduling an email to be sent to them with the link at a time of your choosing. You also have the option to include a personal message.

I have narrated all of my audiobooks myself, including this one, which was recorded at a studio in Montreal. It was a team effort: Patrice, the sound engineer; Gordon, the audio director; Lalya, my Greek classicist and pronunciation coach; and myself — we all did our level best to make the story of Socrates really come alive for you in this recording. So we’re all heartened to see that the first batch of reviews have been a straight-run of five star ratings.

Audiobooks provide a convenient way to send a gift to someone regardless of where they live. You can even schedule exactly when you want the recipient to get it in their inbox — it can reach them on Christmas morning, if you want. The links in this email are for the US version but you can easily do the same thing from audible in other countries, including the UK, Canada, and Australia.

This book is Whispersync compatible, which means you can switch seamlessly between reading a the Kindle version and listening to the audiobook, as your progress will be tracked across both.

Early Reviews of the Audiobook

Early Reviews of the Audiobook

Brilliant Teacher of CBT and Socrates! I've learned more about CBT from Donald J. Robertson than in all my years in grad school. The way he weaves the story of Socrates and CBT together is a joy to listen to. If you haven't heard him talk about the book's release on several podcasts, you should also look around and check them out. To listen to him riff on Socrates and CBT is like being at the table with someone brilliant and getting a chance to soak up the conversation. The back story on Socrates alone opened my eyes to the richness of this historic and beautiful tale of a man who died for what he believed in. Donald J. Robertson is a fantastic writer and storyteller with an incredible voice. Bravo! — Anonymous Reviewer

Batting 1,000. As with How to Think Like a Roman Emperor I end the book in tears. A beautiful telling of the life and times of Socrates. Robertson’s interpretation of Socrates’ interactions with friends and colleagues adds a richness and depth to a man we don’t have absolute certainty about. Many of Socrates’ personal experiences and his personal conversations have been lost to time. Robertson’s telling is the sequel to How to Think Like a Roman Emperor we didn’t know we needed. — Anonymous Reviewer

Bringing Socrates to life. Socrates is the antidote to the fear of “stoic bros.” Is the situation your problem or your view of the situation your problem? Irrational fears, seeing things how they truly are, being authentically authentic. That’s Socrates! — Anonymous Reviewer

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Great reading voice, Presentation of insights engaging. When I read Donald J. Robertson’s How to Think like a Roman Emperor. It brought these concepts into a format that I could grasp but also would be excited to apply practically. This title exceeded that absorption while in addition making me grow to love and cry during the swan song. In our present times I recommend this book to bring forward the next great statesman to lead in our precious democracy. — Anonymous Reviewer

Very good! A great narrative and detailed biography. Enough high level info on modern CBT. All round very easy listen nad I learned a great deal. Would highly recommend. — Anonymous Reviewer

Outstanding Narration, accessible biography and amazing cognitive strategies all in one wonderful book! There are so many things to like about this delightful book. Much like his excellent text, How to Think like a Roman Emperor, Robertson’s Socrates book does it all. I have spent the year studying philosophy. I feel I have a much better understanding of Socrates’ dialogues after reading this book. Then from other historic texts. Robertson is such an incredible writer. I feel like I’m in the room with these historical figures. I hesitate to call this a self help book, but the reader will learn cognitive strategies to improve their thinking and processing. Sections of the book are meditative. That is what make the audible edition so special. Bravo Donald Robertson on another winner! — Larry W. Patrick

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 10, 2024

How to Learn the Socratic Method

Almost everyone today knows of Socrates, the famous Athenian philosopher, and most people have at least heard of the Socratic Method, the question-and-answer approach to philosophy made famous by him. Very few, however, can describe what the Socratic Method looks like in practice.

Various methods dubbed “Socratic questioning” are used today in teaching law and medicine, and in the practice of psychotherapy, especially cognitive therapy. However, these are only very loosely related to the original Socratic Method. In some regards, they’re quite at odds with the approach Socrates actually employed.

Nowhere is Socrates depicted saying: “Here’s how my philosophical method works…”

We have, as it happens, ample evidence of the Socratic Method, as we can observe it being deployed in the Socratic dialogues written by his students Plato and Xenophon, about eighty of which, in total, survive today. Nevertheless, we lack a clear outline of the method. Nowhere is Socrates depicted saying: “Here’s how my philosophical method works…”

Socrates explained his method by means of a simple teaching aid, a diagram consisting of two side-by-side lists.

It surprises many people to learn, therefore, that tucked away in an obscure dialogue from Xenophon’s Memorabilia Socratis (2.4) we do find an account of Socrates explaining the best way to start learning his philosophical method. In fact, he does so by means of a simple teaching aid, a diagram consisting of two side-by-side lists. Coming from a background in psychotherapy, it struck me that what Socrates described is remarkably similar to one of the most common methods used in cognitive therapy today, known as the “Two-Column Technique”.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Socratic Two-Column TechniqueSocrates was concerned that the young men of Athens were merely learning opinions rather than true knowledge or understanding. One such young man was named Euthydemus. He arrogantly considered himself to be the wisest of his generation because he had amassed a very large and expensive library of books. From them he had learned, and could repeat from memory, what he called the “maxims of the wise”.

Euthydemus was what we call today a “self-help junkie”. He was obsessed with moral and psychological self-improvement. Socrates actually praised him for realizing that the maxims of the wise are worth more than any amount of gold or silver. However, he also put Euthydemus to the test, using the Socratic Method, to see whether he had acquired real wisdom or merely the appearance of wisdom.

Euthydemus aspires to be a great political leader and claims that his studies have made him knowledgeable about what is just or morally right. Socrates therefore draws a simple diagram, consisting of two columns headed “Right” and “Wrong”. (Actually, he writes the Greek letter Δ for dikaiosune, meaning “justice” or what is morally right, and Α for adikia, meaning “injustice” or wrongdoing.) He may have used a wax tablet to do this, although this isn’t specified in the dialogue.

Euthydemus says that it’s particularly easy to name common examples of wrongdoing. Just as today, we all like to complain about politicians and other public figures. Socrates therefore asks him if things like lying and stealing belong under that heading. Euthydemus thinks this seems obvious. We have thereby started to define wrongdoing by giving various examples, and we can infer that the what is morally right probably consists in doing the contrary, and refraining from behaviour such as lying and stealing. This initial phase of the Socratic Method often seems slightly banal, because it elicits answers that Socrates’ partner in the dialogue assumes are common sense.

The Socratic Method proper begins with the next phase of the exercise. Socrates proceeds to ask Euthydemus whether the examples he gave of wrongdoing might be moved across to the other column under certain circumstances in which they become morally right. Over the course of the dialogue, Socrates brings up and discusses, among others, the following counter-examples:

What if an elected general were to deceive the enemy during a war — that may be lying but would it still be considered morally wrong?

What if the same general captures the weapons and armor of the enemy — that might be considered theft but is it wrong?

What if a parent conceals medicine in the food of a small child in order to get them to take it, believing that it will benefit their health — that’s deception but is it morally right or wrong?

What if your best friend is depressed and suicidal and you hide his sword from him for his own safety — that’s deception and theft but does it still constitute moral wrongdoing?

As you can see, the Socratic Method doesn’t consist in asking formulaic questions so much as in using creative thinking to come up with novel and unexpected questions, which potentially expose various exceptions to the original definition, in effect highlighting certain contradictions in our thinking. Socrates was exceptionally good at doing this, in part, because he spent most of his time practising these skills.

Euthydemus is embarrassed to realize that although he started off very confident in his knowledge of what is right and wrong, he is now forced to admit that he feels confused and is unsure how to revise his initial definition. He realizes that he is ignorant with regard to the nature of justice and morality. When Socrates exposed the ignorance of some people they would become very angry with him and would even physically assault him in the street. However, others became eager to educate themselves and devoted to the practice of philosophy.

Socrates explains that he interprets the famous Delphic maxim, Know Thyself, as referring to our ability to grasp the limits of our own knowledge in this way, through self-examination and questioning our assumptions. He says that ignorance of ourselves is perhaps the greatest threat we face in life. We can only truly know ourselves, though, by putting our assumptions about the most important things in life to the test, and finding out whether or not they’re mistaken.

Euthydemus, to his credit, asks Socrates how he should begin applying the Socratic Method in his daily life, if he wants to genuinely improve himself. Socrates advises him to examine his knowledge of what is good and bad in life. In other words, he should start by clarifying his understanding of what is good for us, which, in Greek philosophy, is synonymous with eudaimonia, or human flourishing, otherwise known as the goal of life.

Euthydemus says that physical health is obviously good for us, as is everything that contributes to it, whereas their opposites, sickness and whatever damages our health, are bad. Once again, this appears like common sense to him, and he assumes most people would agree. Socrates points out, however, that being in good health and able-bodied might, in some circumstances, be the reason we’re recruited for a disastrous military campaign or as sailors on a fatal expedition. The weak and sickly who are left at home, ironically, might be the only survivors. (Something like this actually happened during the notorious Sicilian Expedition when forty thousand Athenians and their allies were lost in the most catastrophic military campaign of the Peloponnesian War.)

Euthydemus is perplexed and offers instead that wisdom is surely something inherently good. Many wise men, says Socrates, have been captured and enslaved by powerful kings because of their technical expertise, and others have been persecuted by those who were envious of their cleverness. He seems to think, in other words, that whether or not we consider wisdom to be good rather depends on how we define its meaning. Many men with a reputation for wisdom have fallen into misfortune, and do not provide good examples of flourishing.

Xenophon concludes the dialogue as follows:

Many of those who were treated in this way by Socrates stopped going to see him; these he considered to lack resolution. But Euthydemus decided that he would never become a person of any importance unless he associated with Socrates as much as possible; and from that time onwards, he never left him unless he was obliged to, and he even copied some of Socrates’ practices.

Presumably, Euthydemus adopted the two-column technique that Socrates had taught him, and continued to use the Socratic Method to examine his own preconceptions about the most important things in life.

Conclusion

ConclusionSocrates viewed wisdom more as a cognitive skill than a set of beliefs. You therefore can’t acquire wisdom just by memorizing the sayings of wise men. You have to test your skills by engaging in philosophical dialogue about the goal of life, human flourishing, virtue, and other important concepts. Although there’s certainly more to the Socratic Method than this, the two-column technique provides a very simple way of honing some of the core skills underlying it. As Socrates makes clear in this dialogue, it’s a good starting point, if you’re interested in applying philosophy to self-improvement.

As a cognitive therapist, it struck me that Socrates was teaching his friends and followers cognitive flexibility. That’s the term modern researchers use for our ability to overcome rigid assumptions or tunnel vision and see events from a broader variety of perspectives. We know that cognitive rigidity, overgeneralization and selective thinking, is associated with mental health problems like clinical depression and certain anxiety disorders. Socrates was a creative thinker, whose philosophical method treated cognitive flexibility as a trainable skill. For example, a depressed individual may assume that losing their job is something shameful or catastrophic. Socrates would help them identify examples of circumstances in which it might actually turn out for the best. In my experience, incidentally, although losing a job is often very stressful and challenging, in every single case I can recall, it did lead on to better things for the individual concerned.

The only thing I want to add to what Socrates said is that today, in cognitive therapy, we use the two-column exercise in other ways. I think he would approve of these and, indeed, we can arguably find traces of similar practices in the Socratic dialogues. There are three variations worth mentioning here.

Evaluating evidence. The most common question in traditional cognitive therapy is “Where’s the evidence for that?” We often use to columns to list the evidence for and against an unhealthy belief. The second phase consists in asking whether some of the evidence for the belief might be illusory or weaker than it seemed at first.

Evaluating costs and benefits. This is the familiar concept of weighing up the pros and cons of a belief or a way of behaving, such as a specific coping strategy. What do you gain? What do you lose? The second phase is to ask yourself whether some of the pros and cons could be enhanced in some cases, and reduced or prevented in others.

Comparing good and bad versions. This is less common but I think it’s important. How would you distinguish healthy problem-solving from unhealthy problem-solving — the latter is often synonymous with morbid rumination or worry. What would distinguish a good way of using relaxation techniques, or mindfulness techniques, or assertiveness techniques, etc, from a bad way?

Perhaps the written two-column exercise described by Socrates in the Memorabilia was just a off-the-cuff moment that had no influence on later generations of philosophers. After all, it’s largely overlooked today. When I was researching my recent book, How to Think Like Socrates, though, I noticed something similar in Roman literature.

Nearly five centuries after Socrates lived, a Roman poet named Persius wrote a satire about the lectures attended, in his day, by students of Stoic philosophy. “Has philosophy taught you to live a good, upstanding life?” asks Persius. You must, he adds, be able to tell what is true from false appearances, “alert for the false chink of copper beneath the gold.” […] He follows this by saying something that echoes the Socratic dialogue we’ve just discussed: Have you settled what to aim for and also what to avoid, marking the former list with chalk and the other with charcoal? — How to Think Like Socrates

If this Stoic teacher had read the Memorabilia, he would have proceeded to ask his young students under what circumstances the things they assumed should be aimed for in life might actually belong under the heading of things to be avoided. Why don’t we ask this in schools today?

We can find many lists of opposites scattered throughout the Stoic literature. In some cases, it sounds as if the Stoics were, indeed, using them to reflect on possible exceptions, just as Socrates does in Xenophon’s dialogue above. For example, according to Diogenes Laertius, the early Stoics taught that the wise man possesses the following qualities.

Apatheia, in the sense of being free from unhealthy (pathological) passions but not apathy, in the sense of being hard-hearted and insensitive toward others.

Indifference to praise or censure, in the sense of being free from vanity but not indifference to other people’s opinions in the sense of being thoughtless.

Toughness in the sense of being austere and not swayed by bodily pleasures but not tough, in the sense of being overly-critical and severe toward others.

Virtue in the sense of earnestly seeking one’s own improvement, and avoiding evil in our lives but not the cultivation of a reputation for virtue through the (phoney) appearance of “virtue” in our speech and behaviour.

(I’m paraphrasing here because the original Greek is very concise and a little ambiguous but this is what I take him to mean.)

Clearly, an effort was made here not only to list the main qualities considered good but also to ask a follow-up question such as: Under what circumstances might each of these potentially be moved to the “bad” column?

I hope you’ve learned how easily the central cognitive skills required for the Socratic Method can be practiced just by drawing two lists. Ask yourself whether the things you assumed went in one column might, under some circumstances, go better under the opposing column. That requires creative thinking. Socrates practised doing something similar every day of his life. If you did this for a few weeks, though, I think you’d begin to notice the benefits. Training yourself in the Socratic Method leads, as I said earlier, to increased cognitive flexibility. It helps you to question things more deeply and see through the assumptions made by others. It’s our best defense against uncritical thinking.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 8, 2024

Early Reviews of "How to Think Like Socrates"

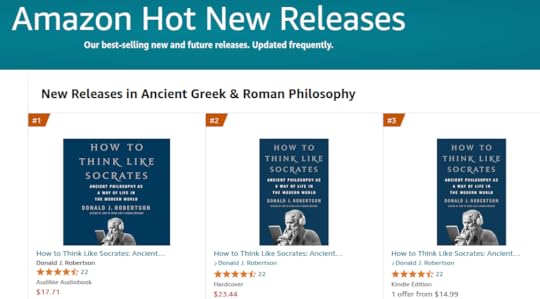

How to Think Like Socrates was released in the US and Canada on 19th November, and has already been many of you online. Thanks to everyone for your support!

The book currently has 4.16 stars on Goodreads, 4.6 stars on Amazon US, and 5 stars on Audible for the audiobook. Barnes & Noble picked it as one of their recommended titles, and the audiobook has been ranked Amazon’s number one new release in Greek philosophy since it was published. If you have read or listened to the book, and haven’t already done so, please consider leaving a review online.

A practical application of his philosophy to contemporary problems, this book makes the wisdom of Socrates more accessible than ever before. — Barnes & Noble

Some More Reviews

Some More Reviews“Robertson draws incisive links between modern psychotherapy to ancient philosophy, bringing Socratic dialogues to life through colorful narration and detail. It’s a creative look at the enduring relevance of an ancient thinker.” — Publisher’s Weekly

“The explanation of Socrates, particularly a section walking readers through the Socratic Method — the question-based method Socrates used to teach students — is the strongest portion of Robertson’s book." — The Associated Press

“How to Think Like Socrates is a definite recommendation and should find its way to your bookshelf. […] The accessibility of the information and flow of the book makes it enjoyable and educational to read. That’s why this book will become an instant classic, along with Donald Robertson’s previous books.” — Via Stoica

“In How to Think Like Socrates, Donald Robertson unites the ancient lessons of Socrates with the modern principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The book is an easy-to-read dance between historical events, Socratic Dialogues, and modern CBT.” — Sam Alaimo

A Guide To How To Think Like Socrates4.46MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload this illustrated PDF explaining the characters, events, and practical techniques in the book.Download

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What other Authors Said“One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! Highly recommended!” —Tom Morris, author of If Aristotle Ran General Motors

“Wonderful . . . In our modern world that swirls with half-truths and disinformation, we need nothing less to awaken us from our illusions.” —Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom

“An intriguing and original book, engagingly written and highly accessible.” —Chris Gill, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Thought, Exeter University, and author of Learning to Live Naturally

“A fresh and original introduction to the figure of Socrates, blending philosophy, history, and psychotherapy.” —John Sellars, reader in philosophy at Royal Holloway, University of London and author of The Pocket Stoic

“Don Robertson is your trusty and insightful guide to the life, times, and thought of the most important philosopher in the western tradition.” —Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic

Hector reading his copy. The book is dedicated to him.

Hector reading his copy. The book is dedicated to him.Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 5, 2024

The Moral Maze: Who and what is 'toxic'?

Photo by Zach Savinar on Unsplash

Photo by Zach Savinar on UnsplashYesterday, I appeared as an expert “witness” on the BBC Radio 4 program, Moral Maze, in which we were discussing the concept of “toxic” workplaces and relationships. I appear toward the end of the show for 5-10 min talking about “toxicity” from the perspective of Socrates and the Stoics.

In my view, the term “toxicity” has pros and cons but overall it’s quite an unhelpful concept. On the positive side, it can help people to label their problem if that provides them with a common language that lets them connect with others who have encountered similar problems, as they may learn ways of coping. However, relying too much on the term “toxic” creates several problems:

It risks disowning agency by attributing our emotional response exclusively to the external environment, or actions of others, rather than attributing our stress, at least in part, to our own thinking, values, coping strategies, etc.

It lumps together a wide variety of different problems, in a confusing way, which range from overt sexual and racial abuse, and other unethical or even criminal behaviour, to covert or indirect inappropriate behaviour, such as passive aggression, or subtle discourtesy.

In some situations the “toxicity” may consist in actual harm to our interests, such as prejudice that interferes with our performance at work or limits our career progression. In most cases, perhaps, the harm takes the form of stress or emotional disturbance, which is largely, if not exclusively, cognitively mediated. To paraphrase Epictetus, it’s not the workplace that’s causing you stress but rather your opinions about it. The “toxicity” is perhaps best viewed, in such cases, as caused by the interaction between the external environment and our subjective thoughts and feelings. What one person experiences as intolerably disrespectful, for instance, another might welcome as directness. One man’s meat is another man’s poison.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

However, the Stoics emphasized that only the ideal Sage is completely in control of his subjective feelings, and he (or she) is as rare as the Ethiopian phoenix. Maybe Socrates or Diogenes the Cynic were perfect sages, but, for instance, Marcus Aurelius isn’t sure we can ever know this for certain. The Stoics consider it foolish, therefore, to assume that other people are perfectly wise. As Marcus famously does at the beginning of Meditations book 2, we should prepare ourselves for the fact that people in general are flawed. We are all emotionally sensitive to certain triggers, whether we like it or not.

Perhaps surprisingly, therefore, the Stoics do not think we should be callous toward other people who complain of “toxic” workplaces or relationships. Epictetus tells his students to show empathy outwardly for the suffering of others, while inwardly reminding themselves that it’s due, largely, to their way of thinking about events. He tells his students “you are not Socrates”, but they should aspire to make progress in that direction, toward wisdom, by learning to take ownership for their own thoughts and feelings.

When we call a situation or relationship “toxic”, we’re typically alluding to the notion that it’s gradually harming us like a poisonous chemical — it’s like lead in the water. I think a better simile, though, would be that stress is like an allergic reaction. Poisons affect more or less everyone but not everyone has the same reaction to allergens — some people are more allergic to inappropriate behaviour at work than others. Allergies can go away over time, or they may get worse. It’s our own body that’s harming us, though, through its reaction to the allergens in our environment. If you’re mildly allergic, you might be able to deal with the symptoms. If you’re highly allergic to something, though, it makes sense to either remove the cause or avoid the situation, even if other people don’t have the same reaction. As Epictetus tells his students, if there’s a little smoke in your house, live with it, but if there’s too much smoke for you, you would probably be better to leave. Of course, if we know people are allergic to something, especially if it’s a common allergy, it would be respectful to remove it. Some restaurants avoid using peanuts altogether; others warn diners that there could be traces of peanut in their food. (Peanut allergies can make people very sick or even kill them.)

In a workplace, the person most responsible is, of course, the person in a leadership position, as they have most control over the environment. The show didn’t touch on this but under the Health and Safety at Work act, incidentally, British employers actually have a legal obligation to assess and prevent risks to the mental health of their employees caused by workplace stress and issues such as bullying or harassment, and so on.

A good leader, or CEO, will recognize that people will experience certain factors as “toxic” because of their individual character, and also because of social norms. It would be foolish and unrealistic to expect employees to, like Diogenes the Cynic, transcend all social norms, e.g., and be impervious to even the worst insults. We should set standards for appropriate behavior, therefore, based on social norms, while simultaneously recognizing that the harm caused is, typically, mediated by our thinking, which could be different. People have different levels of emotional resilience and what is appropriate in one setting, or acceptable in one culture, may be quite different from the norm in another.

Does that mean that Stoicism is victim blaming? No. Epictetus clearly states that those ignorant of Stoicism blame others for their problems. Those who are partially-educated blame themselves. However, the wise blame neither themselves nor others for their problems. They view their stress as due to the interaction between their subjective values and external events, but their values are determined by nature and nurture, such as genetics and cultural norms. We can, theoretically, change our acquired beliefs, and ascend to the emotional resiliency of a Socrates or Diogenes, but that’s an aspirational goal. The Stoic Sage is like the individual equivalent of a “Utopian” society — we’re not there yet! Even Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, did not claim to be perfectly wise or resilient.

In psychotherapy, or coaching, if someone arrives at the first session complaining of a “toxic” relationship or workplace environment, the first thing we always have to do is ask them to go beyond that label, and describe much more specifically what is happening and how they are responding. That leads to a multi-factor conception of what is causing their stress — it’s due to a combination of things. They usually have direct control over some aspects, indirect control over some, and no control over others. Change inevitably requires taking more responsibility for the aspects under our direct control: our own thoughts and actions.

The Moral Maze[Episode listing from the BBC Radio 4 website.]

The allegations about Gregg Wallace’s behaviour on set have been described as being part of a "toxic environment". Once primarily used to describe plants, arrows and chemicals, “toxic” - which is defined as “poisonous” – only relatively recently started being applied to workplaces and people: parents, siblings, neighbours, exes and co-workers.

Those who have experienced a toxic work culture or colleague might describe a deterioration in their personal and professional well-being – the causes of which may be difficult to define – or prove – on their own. While sexual harassment, racism, and bullying should be clearly understood, a toxic environment may involve more subtle things at play: a lack of trust, unrealistic expectations or an atmosphere of negativity. Here, employees might point to a power-dynamic in which they feel infantilised and gaslit by their bosses.

But is the debate around “toxic” environments or people helpful? What are we to make of a term which hinges on how an aggrieved person feels rather than the defined behaviour of the perpetrator? Is that an important redress for those who have for too long suffered in silence? If a boss sets a negative tone in an office, due to their own pressures and stresses, does that make them “toxic”? When does an off-colour joke become “toxic”? Some psychiatrists think that labelling something or someone as “toxic” risks writing off certain behaviour or people, rather than confronting them and dealing with it.

What should – and shouldn’t – we be prepared to accept in a workplace or in a relationship? Is it possible to detoxify cultures like the entertainment industry, which thrives on the egos of the “talent”? Can people change? When is it OK to cut off a “toxic” relative?

Chair: Michael Buerk

Panel: Sonia Sodha, Konstantin Kisin, Matthew Taylor and Anne McElvoy

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 3, 2024

Marcus Aurelius on Socrates

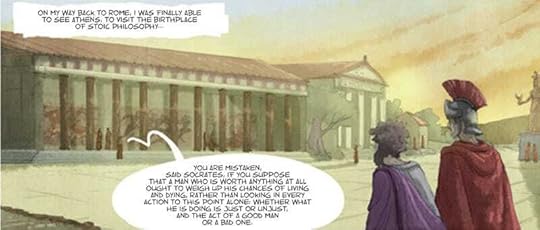

In 175 AD, probably for the first time in his life, in his mid-fifties, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, set foot in Athens. It was in fact a pilgrimage for him. During of the “War of Many Nations” he’d been fighting along the Danube frontier, he had taken a sacred oath that he would travel to Athens, if victorious, and be initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. Although these rites ended with initiation at the Temple of Demeter in nearby Eleusis, they began in the centre of Athens, outside the Stoa Poikile, or painted porch, the ancient home of Stoic philosophy.

Get How to Think Like Socrates

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. Robertson

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonAs Marcus stood upon the Stoa Poikile, he would have gazed across the Agora where Socrates once discussed philosophy, and where he was later put on trial, imprisoned, and executed. Beyond the Agora, Marcus would have seen the Temple of Athena known as the Parthenon. At that time a colossal statue of the goddess of wisdom looked down on Athens, from atop the Acropolis. Most of the drama of Socrates’ life had unfolded within the bounds of the Agora, under the gaze of Athena.

It must have been a humbling experience for Marcus to know that he was walking in Socrates’ footsteps. According to the Historia Augusta, the emperor had “ever on his lips” the saying attributed to Socrates in Plato’s Republic that “those states prospered where the philosophers were kings or the kings philosophers.”

The Stoic school appears to have been viewed, at least by some, as a Socratic sect.

Socrates and the StoicsSocrates was, in a sense, the godfather of Stoicism. The Stoic school appears to have been viewed, at least by some, as a Socratic sect. For example, Diogenes Laertius, claims a Cynic-Stoic succession descended directly from Socrates through his friend and follower, Antisthenes. Socrates taught Antisthenes, who (reputedly) taught Diogenes the Cynic, who taught Crates of Thebes, who taught Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school. We’re also told that Zeno received a pronouncement from the god Apollo, via his priestess at Delphi, instructing him to “take on the colour of dead men”. He was awakened to the meaning of this cryptic statement when he stumbled across the second book of Xenophon’s Memorabilia Socratis, which contains a famous speech by Socrates, an exhortation to the life of virtue and philosophy. Henceforth, the Stoics appear to have viewed Socrates as their supreme role model. Centuries later, for instance, we find the great Stoic teacher, Epictetus, repeatedly telling his young students to emulate Socrates, and ask themselves what Socrates would have done in various situations.

Marcus Aurelius narrowly missed the opportunity to meet Epictetus in person but he probably knew men who had attended his lectures. For example, Marcus’ favourite Stoic mentor, Junius Rusticus, gifted him a copy of the Discourses of Epictetus, from his own private library — possibly meaning that Marcus read the words of Epictetus before they were known to the public. Marcus quotes Epictetus, throughout the Meditations, more often than he does any other thinker, and it seems clear that he saw himself as a follower of Epictetus’ branch of Stoicism.

There were reputedly eight volumes of the Discourses originally, only half of which survive today. Marcus quotes from the Discourses known to us but he also quotes other sayings of Epictetus, suggesting that he had may have read the missing Discourses. It may even be that some of the passages in the Meditations that we attribute to Marcus are actually quotes or paraphrases from these lost volumes of Epictetus’ teachings.

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonSocrates in the Meditations

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonSocrates in the MeditationsSo to what extent does Marcus follow Epictetus’ advice to emulate Socrates? Well, Marcus compares his adoptive father, the Emperor Antoninus Pius, to Socrates, and urges himself: “Do everything as a disciple of Antoninus.” He goes into great detail, twice in the Meditations, listing the traits of Antoninus that he seeks to emulate in his own life. However, the most important quality that the two men had in common, according to Marcus, was their self-control.

And that might be said of [Antoninus] which is recorded of Socrates, that he was able both to abstain from, and to enjoy, those things which many are too weak to abstain from, and cannot enjoy without excess. — Meditations, 1.17

Marcus adds that, in his eyes, having the strength to abstain from certain pleasures, and the self-discipline to experience pleasure without losing control “is the mark of a man who”, like Socrates and Antoninus, “has a perfect and invincible soul.”

Marcus also cites Socrates as one of his heroes, alongside Heraclitus and Diogenes the Cynic. Socrates, and these other philosophers, Marcus says, are more deserving of our admiration than famous military leaders such as Alexander the Great, Pompey the Great, and Julius Caesar. Philosophers such as Socrates, he says, were familiar with the true nature of things, their form and substance, and unlike Alexander, Pompey, and Caesar, their intellects were not enslaved by passions — whereas these rulers were puppets of their own fear and anger the philosophers were truly free men (Meditations, 8.3).

Elsewhere Marcus lists Socrates alongside Heraclitus, and Pythagoras (here replacing Diogenes), as examples of particularly “noble philosophers” that he greatly admires. Marcus seems to imply that Socrates, along with others, has been unharmed, in a sense, by death and that during life he maintained goodwill toward all men, even those who attacked him, presumably including those who brought him to trial, and had him executed.

As to all these consider that they have long been in the dust. What harm then is this to them… One thing here is worth a great deal, to pass your life in truth and justice, with a benevolent disposition even to liars and unjust men. — Meditations, 6.47

In another passage, Marcus says that Socrates was killed by “lice”, metaphorically, the men who prosecuted him and had him executed for impiety and corrupting the youth. He links this to an argument about accepting our own mortality derived from Plato’s Apology, where Socrates prepares himself to face a death sentence.

You have embarked [on life], you have made the voyage, you have come to shore. Get out. If indeed to another life, there is no want of gods, not even there. But if to a state without sensation, you will cease to be held by pains and pleasures, and to be a slave to the bodily vessel, which is as much inferior as that which serves it is superior: for the one is intelligence and deity, the other is earth and corruption. — Meditations, 3.3

Marcus also singles out as particularly noteworthy this remark about Socrates, which he probably derives from Plato’s Crito.

Socrates used to call the opinions of the many by the name of Lamiae — bugbears to frighten children. — Meditations, 11.23

In Greek tragedy, Queen Lamia was an African ruler who turned into a child-devouring monster, after all of her own children were snatched from her by the jealous goddess Hera. Her name became associated with bogey masks, used to frighten small children. Marcus is referring, like Socrates, to our fear of death, though. The majority of people have opinions about death, and other misfortunes, that terrify them. The wise man looks behind the frightening mask, though, in order to understand the reality underneath.

The Life of ReasonIn one place, Marcus reproduces a fragment of Socratic dialogue, which goes roughly as follows:

Socrates: Do you want to have the souls of rational or irrational creatures?

Others: Rational ones.

Socrates: What sort of rational creatures, healthy ones or unhealthy ones?

Others: Healthy.

Socrates: Why then do you not seek for them?

Others: Because we have them.

Socrates: Why then are you fighting and quarreling? — see Meditations, 11.39

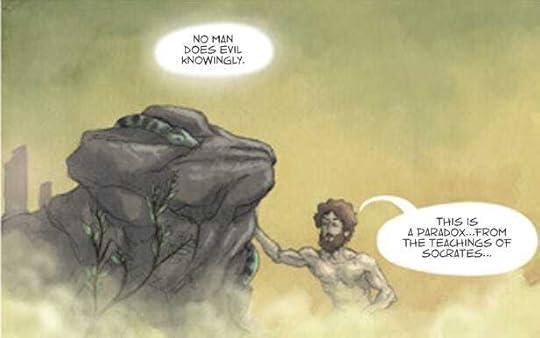

This passage does not exist in any surviving Socratic dialogues. It does look typically Socratic, although the argument is much more concise than the ones we typically find in Plato or Xenophon. Socrates, as usual, begins with questions that seem almost silly, rhetorical questions, where the answers appear so obvious they’re not worth asking. Of course, everyone wants to be capable of reasoning, and we would all like to believe that we do so fairly well throughout life.

Socrates usually works more slowly toward a paradoxical conclusion but here it comes quickly. It is our very belief that we are already rational, or wise, that prevents us from making an effort to improve ourselves. The Socratic Method, we’re repeatedly told, was designed as a cure for such intellectual conceit. We have to admit that we’re being irrational before we can become philosophers, in pursuit of reason and wisdom. Everyone wants to be wise but, ironically, nobody bothers trying to become so, because we arrogantly assume that we have enough wisdom already!

In this mini-dialogue, Socrates points to the fact that the unnamed others are bickering with one another. This provides evidence that they’re not actually behaving very rationally. Marcus places a lot of emphasis, throughout the Meditations, on the Stoic teaching that man is by nature both rational and social. He treats anger and hatred as symptoms of underlying irrationality, which we urgently need philosophy to cure.

Marcus keeps reminding himself that as naturally rational beings we should view nothing as better than reason, which he considers divine.

But if nothing appears to be better than the deity [reason] which is planted in you, which has subjected to itself all your appetites, and carefully examines all the impressions, and, as Socrates said, has detached itself from the persuasions of sense, and has submitted itself to the gods, and cares for mankind; if you find everything else smaller and of less value than this, give place to nothing else. — Meditations, 3.6

Stoics must make a continual effort to value reason above all, because there is a tendency to place more value on other things, which appear useful to us in life, such as wealth or reputation. Marcus says that we should place some value on external things but we have to be very careful to distinguish whether they’re “useful” insofar as they serve our goals as rational beings, or our appetites as animals.

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonWas Socrates a Sage?

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonWas Socrates a Sage?The Stoics were careful to avoid putting their role models on a pedestal and turning them into idols, though. They insisted that no man was perfectly wise. Most other schools of Greek philosophy were named after their founders — the Pythagoreans, Platonists, Aristotelians, Epicureans, etc. The Stoics were briefly known as “Zenonians”, after their founder Zeno, but soon dropped this and became known after the Stoa Poikile, the public building where they originally met one another to talk philosophy. Marcus, likewise, continually reminds himself that his heroes are merely mortal — the universe, the river of time, is like a furious torrent, which has swept along and swallowed up countless men like Epictetus and Socrates. (Meditations, 7.9).

He goes further and reminds himself that he cannot know for certain that other men are not superior in character to Socrates. All he has are some stories about the words and deeds of a man, Socrates, who died over five centuries earlier.

For it is not enough that Socrates died a more noble death, and disputed more skillfully with the Sophists, and passed the night in the cold with more endurance, and that when he was bid to arrest Leon of Salamis, he considered it more noble to refuse, and that he walked in a swaggering way in the streets — though as to this fact one may have great doubts if it was true. — Meditations, 7.66

These are well-known anecdotes about the life of Socrates, which Marcus could have found in Plato’s Symposium, Apology, and Phaedo. He recognizes that these stories cannot be taken at face value. Nevertheless, he finds inspiration in them.

The inner character of Socrates is more important to Marcus than his outward behavior although it cannot be known for certain. He asks himself whether Socrates was, as he seemed to have been…

Content with being just toward men and pious toward the gods in his actions

Neither frustrated by other men’s villainy

Nor going along with them, gullibly, and enslaved by their ignorance

Not experiencing as strange or intolerable any events that befell him

Nor allowing his intellect to be swayed by physical sensations, such as pleasure or pain — see Meditations, 7.66

I think Marcus means, paradoxically, that we should spend time trying to analyze the character of Socrates, even though we can never know for certain what he was like.

Anecdotes about SocratesMarcus mentions another popular anecdote about Socrates:

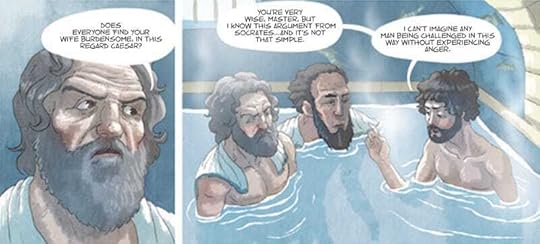

Consider what a man Socrates was when he dressed himself in a skin, after Xanthippe had taken his cloak and gone out, and what Socrates said to his friends who were ashamed of him and drew back from him when they saw him dressed thus. — Meditations, 11.28

Socrates, famously, only had one cloak, so the implication is that he was left with nothing to wear except an animal pelt, which probably shocked Athenians as it would seem like something a foreign barbarian might wear.

Xanthippe, Socrates’ young wife, became known as a shrew, although by some accounts Socrates praised her both as a mother and a wife. She reputedly had a quick temper. Respectable Greek women, at this time, seldom left the house except at allotted times. This story is not in the surviving Platonic dialogues but it is perhaps linked to an anecdote reported by Diogenes Laertius, who says that Xanthippe tore the cloak from Socrates’ back, out in public, in the Agora. When onlookers urged Socrates to strike her in punishment, the philosopher refused to do so because he said he would merely be providing a spectacle for their entertainment. The gist of both stories is probably that Socrates was unperturbed by something others found shocking and insulting. He merely shrugged it off as a harmless tantrum and went on his way.

Of course, it’s tempting to compare this to what we know about Marcus Aurelius’ wife Faustina, whose gossips claimed was unfaithful to him, and a source of much trouble. We’re told satires were performed at Rome that ridiculed her infidelity and portrayed Marcus as a cuckold. Yet in private, Marcus praises her affection and loyalty, so these rumors may have been unfounded or exaggerated. Marcus took inspiration from Socrates as someone who could turn a blind eye to other people’s opinions about his wife’s behavior, perhaps because he was convinced the criticisms of her character were unfounded.

Another anecdote, of uncertain origin, but similar to one reported in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, is mentioned by Marcus:

Socrates excused himself to Perdiccas for not going to him, saying, “It is because I would not perish by the worst of all ends”; that is, I would not receive a favor and then be unable to return it. — Meditations, 11.25

The point of this tale seems to be a familiar Greek piece of wisdom about avoiding indebting yourself to others. We have to be careful about accepting favors because although the benefits may seem appealing, we often sacrifice our freedom in doing so.

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonConclusion

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, copyright Donald J. RobertsonConclusionMarcus Aurelius wrote the Meditations over five centuries after Socrates died. Marcus was, in other words, as far removed in time from Socrates as we are from the European Renaissance and the invention of the printing press. You could almost say that to Marcus Aurelius, Socrates was already an “ancient” philosopher. Nevertheless, Marcus, following Epictetus and other Stoics, continues to take Socrates as one of his main role models in life.

There are many other passages where Marcus appears to draw on ideas that ultimately derive from earlier writings about Socrates. One of the most striking is in Meditations 11.18, where Marcus refers to contemplation of Socrates’ famous paradox that no man does evil willingly, as a remedy for anger. However, as we’ve seen, there are enough instances where Marcus mentions Socrates by name to discuss in one article, and plenty of indirect references left to discuss another time.

November 30, 2024

Download "A Guide to How to Think Like Socrates"

I created this 14 page illustrated PDF handbook, with the help of two graphic designers. It contains an overview of some of the main characters, events, and practical exercises, from my new book, How to Think Like Socrates, and everyone is welcome to download a copy. (Some of you who preordered the book were having technical issues with the Scribd link, etc, so I’m just emailing everyone on Substack the file instead.)

A Guide To How To Think Like Socrates4.46MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload our free illustrated handbook, exploring characters, events, and practical advice, from How to Think Like Socrates.DownloadAlternatively, you can also download the PDF directly from Google Drive.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 28, 2024

Ask me anything about Socrates

I’ll do my best to answer any questions you want to ask over the next couple of days. I’m not a professor of classics or philosophy. My book, How to Think Like Socrates, is written more from the perspective of a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist. But I’ve done quite a lot of research on Socrates so I’m happy to share whatever I’ve learned. You can post anything you want but here are some questions for all of you to help get the discussion started…

What might we learn from Socrates that’s relevant to coping with the moral and psychological challenges we face in the modern world?

What do you think we can learn from Socrates that we can’t learn from the Stoics, such as Marcus Aurelius?

What’s your favorite passage, saying, or image, from the Socratic dialogues?

Also, feel free to comment on questions from other subscribers. Thanks for participating in the conversation!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

How can we Measure Wisdom?

In this episode, I speak with Igor Grossmann, a professor of psychology, and renowned researcher in the field of wisdom. Prof. Grossmann directs the Wisdom and Culture Lab at the University of Waterloo, where he investigates the factors that contribute to wise reasoning. He is also the co-host of the On Wisdom podcast. His work has significantly advanced our understanding of how wisdom can be fostered and applied in everyday life.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhat is wisdom?

Is wisdom more like a static trait or a dynamic process?

How does wisdom make use of abstract versus concrete thinking?

What’s the role of intellectual humility in wisdom?

Can you explain what’s meant by open-mindedness, perspective-taking, and compromise-seeking?

How does distanced (third-person) reflection help us to exercise wisdom?

What potential insights could psychotherapists glean from your work?

How does wisdom-based thinking about problems differ from unhealthy forms of thinking about problems such as depressive rumination or anxious worrying?

Are there ways that research on wisdom can help us to cope with problems such as anxiety or depression?

Are you aware of any links between your research on wisdom and what ancient philosophers have said about wisdom?

What’s the relationship between wisdom and inter-group hostility or antisocial attitudes?

Does wisdom lead to co-operation and prosocial attitudes?

Links

LinksThe Wise Mind Balances the Abstract and the Concrete

Explaining contentious political issues promotes open-minded thinking - ScienceDirect

November 27, 2024

Stoicism, Gratitude and Thanksgiving

Gratitude is one of the defining characteristics of the ideal Stoic Sage. We know this because one obscure source, Pseudo-Andronicus, provides a classification of Stoic virtues in which “gratitude” (eucharistia) is classed as a species of “justice” (dikaiosune) and defined as “the knowledge of to whom and when one should provide thanks and how and for what.” We can also tell that this was an important virtue in early Stoicism because, although it’s lost today, Cleanthes, the second head of the Stoic school, wrote an entire book titled On Gratitude (Peri Charistos), dedicated to the subject.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The sculpture Socrates was working on would depict three goddesses, called the Graces, or Charites. They personified the virtues involved in graciously bestowing and receiving favors. One maiden offered a precious gift, another received it with gratitude, and a third repaid the giver. The three Graces symbolized this virtuous cycle by dancing together in a circle. As soon as Socrates was set to work on this piece, dedicating his entire day to its preparation, he found himself besieged by new questions. What are generosity and gratitude? What do they look like in their perfect form? — From How to Think Like Socrates

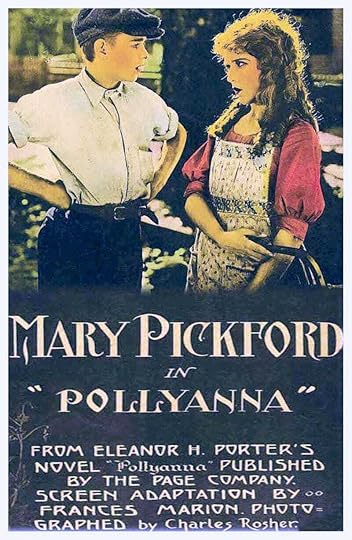

In this article, I’m going to explain some little-known reasons for the importance of gratitude in Stoicism. I’ll also describe a psychological strategy for cultivating gratitude found in Epictetus, which I’ll compare to the “Glad Game” found in a popular early 20th century children’s book, called Pollyanna.

The Charites were associated with “gracious”, or charitable, behaviour, both the giving and receiving of gifts, and of gratitude or thanks.

The Greek word for gratitude, charis, is related to “joy” (chara) — gratitude means rejoicing in, or at least appreciating, what we have received. Charis can also mean “grace”, however, as in the Three Graces or Charites. According to legend, it was actually Socrates, during his early career as a sculptor, who made the statue of them that once stood at the entrance to the Athenian Acropolis. The Charites were associated with “gracious”, or charitable, behaviour, both the giving and receiving of gifts, and of gratitude or thanks.

Another Stoic philosopher, Cornutus, wrote in his Compendium of Greek Theology:

They [the Charites] are presented naked to make another point, which is that even those who have no possessions are able to provide help with some things, to do many useful favours; and that one does not have to be really wealthy in order to be a benefactor – as it is said: “in the gifts of a friend, it’s the thought that counts.” And some think that their nakedness indicates that one must be at ease and unencumbered in order to do favours.

He claims that according to one legend, the Graces or Charites are three in number because the first symbolizes the person doing a favour, the second the person repaying it, and there is a third “because it is good when someone who has been repaid does another favour, so that there is no end to it.”

Since one should do good deeds cheerfully, and since favours make their beneficiaries cheerful, first, the ‘Graces’ [Charites] were named in common from joy [chara]…

They were also renowned for dancing in a circle, which Cornutus thinks carried a similar meaning concerning the harmonious nature of bestowing favours reciprocally on one another, receiving them with gratitude, and repaying them in kind.

Seneca mentions that Chrysippus, the second head of the Stoa, had also written about the Charites, although mainly about their relation with other myths. Like Cornutus, Seneca, in On Benefits, is more concerned with the moral symbolism of the Charites:

Some writers think that there is one who bestows a benefit, one who receives it, and a third who returns it; others say that they represent the three sorts of benefactors, those who bestow, those who repay, and those who both receive and repay them. But take whichever you please to be true; what will this knowledge profit us? What is the meaning of this dance of sisters in a circle, hand in hand? It means that the course of a benefit is from hand to hand, back to the giver; that the beauty of the whole chain is lost if a single link fails, and that it is fairest when it proceeds in unbroken regular order. In the dance there is one, esteemed beyond the others, who represents the givers of benefits. Their faces are cheerful, as those of men who give or receive benefits are wont to be. They are young, because the memory of benefits ought not to grow old. They are virgins, because benefits are pure and untainted, and held holy by all; in benefits there should be no strict or binding conditions, therefore the Graces wear loose flowing tunics, which are transparent, because benefits love to be seen.

The Charites reputedly shared the shrine of the Heavenly Aphrodite (Aphrodite Urania), which was located in the Agora of athens, right beside the Stoa Poikile, the home of the Stoic school. An ancient cult was dedicated to the Charites, who were also associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries. It seems likely that their followers may have tried to follow the simple ethical teachings, which the Charites personified for them. In addition to gratefully receiving, and repaying, benefits from others, the Greeks and Romans naturally extended this to include being grateful to the gods. In the Christian era, charis therefore came to refer to the Grace of God, through which all good things were thought to be provided. It is also the source of the Christian term for Eucharist or Holy Communion, although in Greek eucharistia literally means “Thanksgiving”.

The Charites or Three GracesGratitude in Epictetus

The Charites or Three GracesGratitude in EpictetusEpictetus says that one of his Stoic heroes would write letters of praise to himself, eulogizing misfortunes that befell him, and reframing them as opportunities.

And he [Paconius Agrippinus] was such a man (Epictetus said) that he would write in praise of anything disagreeable that befell him; if it was a fever, he would write of a fever; if he was disgraced, he would write of disgrace; if he were banished, of banishment. — Fragment, 56

For instance, Agrippinus reframed being sent into exile as an opportunity to enjoy a pleasant journey through the Italian countryside.

And on one occasion (he mentioned) when he was going to dine, a messenger brought him news that Nero commanded him to go into banishment; on which Agrippinus said, Well then we will dine at Aricia [a nice spot on the road to the port at Brundisium, where the ship would leave for the place of exile]. — Handbook, 56

“Consolation” was, in fact, one of the favours traditionally associated with the Charites. We can speculate that the letters that Agrippinus wrote to himself eulogizing misfortune, by finding reasons to be grateful, may have resembled, at least in some ways, the more common "letters of consolation" that Stoic philosophers typically wrote to their friends.

Gratitude in Marcus AureliusMarcus Aurelius talks about gratitude many times in the Meditations, in relation to accepting and welcoming one’s external fate, which today we call amor fati. There’s one passage to which I’d especially like to draw attention, though.

Do not think of things that are absent as though they were already at hand, but pick out the [the best] from those that you presently have, and with these before you, reflect on how greatly you would have wished for them if they were not already here. At the same time, however, take good care that you do not fall into the habit of overvaluing them because you are so pleased to have them, so that you would be upset if you no longer had them at some future time. — Meditations, 7.27

This is a very nuanced psychological strategy. Marcus notes that humans tend to fantasize about having things they desire by imagining absent things as if they were present but realizes that it is more therapeutic to turn this on its head by imagining present things being absent. When we make a conscious effort to imagine not having the things we value most in life, instead of craving, we may experience gratitude. He warns that this technique should be used cautiously, in order to avoid cultivating too much attachment to the things for which we’re grateful.

Pollyanna’s Glad GameFinally, I’d like to redeem something, which has developed a bad reputation. Today, the term “Pollyannaism” has come to mean irrational and sometimes unhealthy positive thinking. The term comes from the character of a young girl called Pollyanna in the popular 1913 chidlren’s novel of the same name, written by Eleanor H. Porter.

Near the start of the story, Pollyanna describes “the Glad Game”, which features prominently throughout subsequent chapters, to a household servant called Nancy.

“Yes; the 'just being glad' game.”

“Whatever in the world are you talkin' about?”

“Why, it's a game. Father told it to me, and it's lovely,” rejoined Pollyanna.

“We've played it always, ever since I was a little, little girl. I told the Ladies' Aid, and they played it—some of them.”

“What is it? I ain't much on games, though.”

Pollyanna laughed again, but she sighed, too; and in the gathering twilight her face looked thin and wistful. “Why, we began it on some crutches that came in a missionary barrel.”

“CRUTCHES!”

“Yes. You see I'd wanted a doll, and father had written them so; but when the barrel came the lady wrote that there hadn't any dolls come in, but the little crutches had. So she sent 'em along as they might come in handy for some child, sometime. And that's when we began it.”

“Well, I must say I can't see any game about that, about that,” declared Nancy, almost irritably.

“Oh, yes; the game was to just find something about everything to be glad about—no matter what 'twas,” rejoined Pollyanna, earnestly. “And we began right then—on the crutches.”

“Well, goodness me! I can't see anythin' ter be glad about—gettin' a pair of crutches when you wanted a doll!”

Pollyanna clapped her hands. “There is—there is,” she crowed. “But I couldn't see it, either, Nancy, at first,” she added, with quick honesty. “Father had to tell it to me.”

“Well, then, suppose YOU tell ME,” almost snapped Nancy.

“Goosey! Why, just be glad because you don't—NEED—'EM!” exulted Pollyanna, triumphantly. “You see it's just as easy—when you know how!”

“Well, of all the queer doin's!” breathed Nancy, regarding Pollyanna with almost fearful eyes.

“Oh, but it isn't queer—it's lovely,” maintained Pollyanna enthusiastically. “And we've played it ever since. And the harder 'tis, the more fun 'tis to get 'em out.”

It seems to me that Pollyanna resembles a Stoic. To be precise, her “Glad Game” actually sounds not unlike the eulogies Paconius Agrippinus wrote to misfortune, described by Epictetus. It’s important to note that Pollyanna was not denying the facts, and neither was Agrippinus. They’re not indulging in “positive thinking” that’s unrealistic, such as wistful fantasies. On the contrary, Pollyanna accepts the reality that she’s received crutches rather than a doll, and Agrippinus accepted that he’d been banished to exile by Nero. They both make a conscious effort, though, to search for positive aspects of their situations, for which they might experience gratitude, give thanks, or as Pollyanna puts it, be glad.

Although the virtue of gratitude was central to the ancient Stoic ideal, it’s often ignored by self-help authors today. Cleanthes wrote a whole book about it, but nobody has written a modern self-help book about Stoicism and Gratitude. It’s a simple but powerful psychological strategy, though, a potential antidote to toxic emotions like severe anger and depression. Perhaps you can’t even hope to become a Stoic Sage without practising gratitude, and genuine thanksgiving!

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.