Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 8

March 1, 2025

Thank You for the Reviews of "How to Think Like Socrates"

I’ve been writing a lot of original material about the philosophy and psychology of anger recently. For a change, I just wanted to say a big “thank you” to everyone who’s been reviewing my latest book, How to Think Like Socrates. If you’ve read the book but haven’t already done so, please consider rating it or posting a short review on Amazon or Goodreads — these all help the book to find its audience. I narrated the audiobook myself, which currently has 4.8 stars from the first fifty reviewers on Audible.

"Robertson draws incisive links between modern psychotherapy and ancient philosophy, bringing Socratic dialogues to life through colorful narration and detail. It’s a creative look at the enduring relevance of an ancient thinker." ― Publishers Weekly

If you haven’t read How to Think Like Socrates yet, please check out the reviews for yourself. You can also listen to a short sample of the audiobook on Audible, or a longer excerpt that was recently published by Ryan Holiday, via The Daily Stoic podcast.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 27, 2025

Meditation: The View from Above

Thanks to for remastering my audio recording of the View from Above, a guided Stoic meditation exercise.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Check out my article about the Acropolis and View from Above in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius.

You’ll also find an version of the script in this article…

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 25, 2025

Counting the Cost of Anger

When people successfully overcome their own anger, even if in some cases it seems to be the result of a lengthy or complex process, they often sum up the change they’ve experienced by saying things like: “I just realized that it wasn’t worth getting angry anymore.” Anger begins to feel pointless and unnecessary to them.

Consider how much more pain is brought on us by the anger and frustration caused by such acts than by the acts themselves, at which we are angry and frustrated. — Marcus Aurelius

There are behavioural techniques, which can help people to notice when they’re becoming angry and interrupt the emotion. In my experience, though, these often work best when the individual has taken the time to critically evaluate their anger, by questioning their assumptions about how helpful it is. Sometimes it’s necessary to repeat this exercise, e.g., by asking yourself these questions each week, or even every day, until you feel that you’re crystal clear about what you gain or lose by getting angry.

Photo by Laurenz Kleinheider on Unsplash

Photo by Laurenz Kleinheider on UnsplashMost people assume that they already know what the disadvantages are of getting angry. However, when they’re questioned in detail, they usually realize that they’ve been overlooking or minimizing certain aspects of the problem, and change their appraisal of their anger as a result. I have found that by questioning the value of your anger in this way, when you’re not feeling angry, you can just ask yourself, whenever it is next triggered, to rate how helpful it is likely to be (0-100%) in order to “snap out of the trance” and interrupt the escalation of your feelings.

Alternatively, after working through the cost-benefit analysis exercise, when you next begin to get angry, try asking yourself the following question: What does me more harm, my anger or the thing about which I’m angry? That technique is derived from Stoicism. I’ve tested it with over a hundred individuals, most of whom reported an immediate reduction in the intensity of their anger as a result.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Cost-Benefit Analysis ExercisePreliminary QuestionsHow helpful did your anger feel to you, in the heat of the moment, the last time you experienced it (0-100%)?

Looking back on that situation, how helpful do you believe your anger actually was in reality (0-100%)?

Why didn’t you rate both answers the same? (If you didn’t.)

Why didn’t you rate both answers 100%? (If you didn’t.)

How’s your anger been working out for you so far?

How’s it likely to work out for you in the long-run?

Cost-Benefit QuestionsWhat are the benefits of your anger?What do you gain? What pros are there?

Re-evaluateAre those benefits real or illusory?

Could you be exaggerating the value of any of those benefits?

Do those benefits always result from your anger or only sometimes?

How long do those benefits last?

Do other people see those as benefits or as costs?

Could you obtain similar benefits in other ways?

What are the costs of your anger?What do you lose by getting angry? What cons are there?

Re-evaluateMight you be underestimating the seriousness of any of these costs?

What is the wider impact of your anger?

How might it affect your friends and family?

How might it affect people with whom you work or have to interact?

How might it affect your performance at work or your studies?

How might it affect your mental health?

How might it affect your physical health?

How might it affect your overall quality of life?

How might the costs of your anger increase if it continues for years or even decades?

Are you potentially overlooking any other disadvantages of anger?

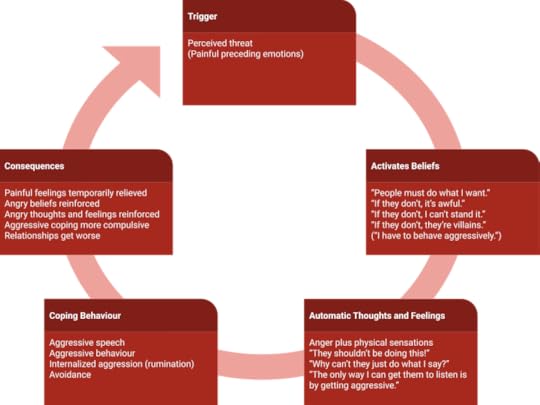

Diagram conceptualizing the vicious cycle of anger in cognitive-behavioural terms Additional Questions

Diagram conceptualizing the vicious cycle of anger in cognitive-behavioural terms Additional QuestionsCarefully distinguish between anger (the emotion) and aggression (the behaviour).

Questions about coping

Does anger sometimes cause you to speak or act aggressively when it's not appropriate or helpful?

Does anger sometimes make you feel that speaking or acting aggressively is the only way you can get what you want?

Could you potentially gain some of the perceived benefits of aggression without feeling anger?

Does anger cause you to overlook other potential ways of coping with problems?

Does anger cause you to do certain things excessively or too forcefully?

Does anger cause you to engage in revenge fantasies or picture yourself speaking or acting aggressively?

Are you getting angry in order to divert your attention from other painful emotions such as hurt, fear, or sadness?

Does anger prevent you from exercising patience or moderation in situations where it might have been helpful to do so?

Questions about reasoning

Does anger cause you to make any mistakes in your reasoning about events?

Does anger interfere with your ability to solve problems?

Does anger cause you to impose unrealistic or overly-rigid demands on yourself, situations, or other people?

Does anger cause you to apply crude solutions to complex problems such as social or interpersonal ones?

Does anger cause you to exaggerate the seriousness of certain problems?

Does anger sometimes cause you to underestimate risks?

Does anger cause you to behave impulsively without thinking through the consequences of your actions properly?

Does anger sometimes cause you to do things that you later regret?

Questions about empathy

Does anger sometimes cause you to attribute hostility to other people and jump to conclusions about what they’re thinking?

Does anger sometimes cause you to focus on negative things about a person and ignore positive things?

Does anger cause you to vilify or demonize other people?

Does anger prevent you from empathizing with other people or being able to understand their perspective? How does that affect the way you communicate with them?

Questions about values

How consistent is anger with your core values? Is it the sort of person you want to be in life?

How would you feel if someone exhibited the same sort of anger toward you that you experience toward others?

Would you want to live in a world where everyone exhibited the same sort of anger as you?

What sort of example do you think you set to people you care about (friends, children, spouse) when you get angry?

What does you more harm, your anger or the thing about which you’re angry?

Review your answers to the questions above and rate, in general, how helpful you now believe your anger is (0-100%)?

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 22, 2025

Video: Stoicism, Anger, and CBT

I recently went to Studio SF in Montreal for a candid conversation about Stoicism, anger, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with host Ivan Nonveiller. You can watch the video below or listen to the audio podcast on Spotify.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 20, 2025

Stoicism and The Moment that Defines your Life

In this episode, I chat with Chuck Garcia, the founder of Climb Leadership International. Chuck coaches executives of Fortune 500 companies on public speaking and emotional intelligence. He is an Adjunct Professor in Columbia University’s Graduate School of Engineering and teaches in their professional development and leadership program. Chuck is also a passionate mountaineer. He is the author of the book A Climb to the Top: Communication & Leadership Tactics to Take Your Career to New Heights, and more recently, his latest book, The Moment That Defines Your Life: Integrating Emotional Intelligence and Stoicism when your Life, Career, and Family are on the Line.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow did you first become interested in Stoicism?

What misconceptions do you think people might have about Stoicism?

Why do you think Stoicism is important today?

What’s your book The Moment that Defines your Life about?

What is a moment that defines your life?

Are there any connections, for you, between Stoicism and mountaineering?

What aspects of Stoicism do you think are most relevant to executive coaching?

How do you see the relationship between Stoicism and emotional intelligence

How do you think Stoicism might help people to avoid getting so angry?

What’s a good way for people to begin learning about Stoicism and applying it in their life?

Links

LinksWebsite: https://chuckgarcia.com/

The Moment that Defines your Life

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 18, 2025

"I talk" and "I thought" for Anger

One of the very earliest modern strategies for managing anger consists in replacing “you talk” with “I talk”. Andrew Salter, the pioneer of assertiveness training and one of the earliest behavior therapists, wrote way back in 1949 that:

The inhibitory are well liked by those who are not close to them. […] They are often colorless, dull, and boring. They avoid the word “I” as being in bad taste. Instead, they say, “shouldn’t one”, and “oughtn’t one.” They mean, “should I”, and “ought I.” — Andrew Salter, Conditioned Reflex Therapy

Salter believed that we should become less inhibited and more assertive, by learning to use the word “I” more often, and by expressing our feelings more openly.

The next […] technique to keep in mind, is the deliberate use of the word I as much as possible. “I like this...” “I read that book and ...” “I want ...” “I heard ...” This will not make you appear priggish, and will sound natural. — Andrew Salter, Conditioned Reflex Therapy

Subsequent generations of psychotherapists embraced the notion of “I talk”, especially in assertiveness training and Gestalt therapy. Indeed, there’s good reason to believe that “I talk” can lead to healthier communication, and reduce anger and aggression, in a number of ways. However, we should probably distinguish between good and bad versions of “I talk”. For example, complaining stubbornly to other people by saying “I need this” or “I’m entitled to that”, can often be counterproductive. However, calmly and assertively stating “I understand this is how you feel”, “I feel differently”, “I think this”, and “I would prefer that”, etc, can be surprisingly helpful.

I like to describe “I talk” and “I thought” as verbal techniques that hold up a mirror to our anger.

In this article, I’m going to describe two specific ways of using “I talk” and “I thought” to help yourself overcome anger. I call it “I talk’ when someone speaks aloud using the first-person pronoun, but I call it “I thought” when they use it in their internal speech. Anger, by its very nature, tends to force our attention outward, at least when we’re talking about other-directed or situation-directed rather than self-directed anger. Sometimes, when we internalize our anger, our thoughts become engrossed in angry rumination, or even revenge fantasies, which also divert attention from what we’re actually doing in the present moment. “I thought” and “I talk” force us to shift our attention back onto our own behavior, and thereby encourage us to take more ownership over our emotions. That alone, in many cases, can be enough to derail anger and replace it with another emotion. I like to describe “I talk” and “I thought” as verbal techniques that hold up a mirror to our anger.

Photo by Fares Hamouche on Unsplash

Photo by Fares Hamouche on UnsplashStoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“I thought”My basic formula for “I thought” looks like this:

“I notice right now that I am angering myself by [specify thoughts or actions].”

Say this to yourself as soon as you notice the earliest warning signs of anger emerging. Make a mental note so that later you can write down your observations, and keep a daily record of the various ways in which you angered yourself in different situations.

First of all, this replaces “I am angry”, “he made me lose my temper”, “this situation makes me furious”, and similar thoughts, expressed grammatically in the passive voice, with “angering myself”, which is in the active voice. If you want to adopt a victim mentality, by disowning responsibility, use the passive voice. If you want to take responsibility for your own emotions, however, use the active voice. This simple piece of grammar weaves a magic spell that allows you to follow up with questions such as: How exactly am I angering myself? It also allows you to ask “Is it angering myself doing more harm than good?”, conclude “I am going to stop angering myself”, and so on. In other words, it can help restore the agency that anger has taken away from you.

The next step is to get specific. By stating exactly how you’re angering yourself, you refocus attention on the root cause of the problem, instead of blaming other people for your emotions. Look for changes in your facial expression such as frowning, angry alterations in your gaze or eye movements such as eye-rolling or staring, tension in your neck and shoulders, or clenching of your jaw, and other voluntary muscular responses. Look for any changes in your breathing, and the corresponding changes in the sound of your voice. Look for changes in your focus of attention — where does all of your attention go and how does it narrow in order to create and intensify your anger? Notice, in other words, what you had previously failed to notice.

The final ingredient is what we call “verbal defusion” or “cognitive distancing” in modern psychotherapy. “I thought” often involves telling yourself things like:

I notice right now that I am angering myself by telling myself “This guy is a jerk, how dare he speak to me that way!”

Referring to your own thoughts, and beliefs, as events taking place, which you can step back and observe with detachment, powerfully changes your perspective from experiencing your anger to observing your anger. That will tend to do two things:

Reduce the intensity of the emotion, which helps in the short-term

Increase your cognitive flexibility, your ability to view the problem from new perspectives, which potentially changes your behavior, and will therefore help you much more in the long-term

I believe that, for many people, it’s even more powerful to notice the underlying patterns in your thinking and label those appropriately using “I thought”. As Albert Ellis put it, we tend to get upset by imposing demands on ourselves, others, or life, which are far too absolute and rigid. For example:

Demanding that other people should always treat me the way I want.

Imposing rigid expectations on life, and specific situations, which are bound to lead to frustration.

Applying perfectionistic standards to ourselves, which we cannot realistically expect to meet.

These type of rigid demands are a recipe for neurosis because when, inevitably, they’re not satisfied, we become upset. It’s as if we’ve programmed our brain with an algorithm that says: “Things should be as I want them to be otherwise I will become upset.” Therapists call this the “Tyranny of the Shoulds”, and it’s particularly obvious in most cases of anger, where people make themselves annoyed by focusing stubbornly on what they believe should or should not be the case, especially what they believe other people should say or do.

Another example would be if you spot typical errors and label them as cognitive distortions such as “I notice right now that I am angering myself by catastrophizing, and blowing things out of proportion again” or “I notice that I am angering myself by jumping to conclusions prematurely about what other people are thinking”, and so on.

Remember to write down your “I thought” statements afterwards in a daily record, if possible. This will make it much easier for you to notice patterns in your behavior, and to respond differently in future situations.

Andrew Salter, a hypnotist, pioneered behavior therapy and assertiveness training“I talk”

Andrew Salter, a hypnotist, pioneered behavior therapy and assertiveness training“I talk”“I talk” is what you say aloud to the other person. Its goal is to replace aggressive behavior, and aggressive speech, with assertive and compassionate speech. It can be difficult to change your behavior in the heat of the moment. It takes practice. However, by using the “I thought” strategy above first, it will become easier to subsequently use “I talk” as well.

Many people have found it helps them simply to use the word “I” rather than “you”, in order to replace anger with assertiveness. However, I think there are probably good and bad ways of using “I talk”. (Obviously, “I hate you!”, for instance, would come across as pretty aggressive rather than being assertive in a constructive way.) So I like to share a formula, which I have found helpful. It looks like this:

“I feel [emotion] about [trigger] so I would prefer it if we could [proposed solution].”

For example, “I feel really angry about you using my toothbrush so I would prefer it if we could please agree to stick to only using our own.”

Moreover, “I talk” can be broken down into easy steps. Begin just by saying “I feel angry”, and focus on shifting your attention from the perspective of experiencing your anger to observing your anger. Even better, notice the emotion that preceded your anger and express that as clearly as you can using “I talk”. In almost all cases, in fact, other-directed anger is preceded by feelings of frustration, shame, hurt, fear, and so on. Learn to notice these often fleeting emotions, accept them, and allow time for them to be processed naturally by your brain. Just accepting them for 5-10 seconds is enough to transform the experience for many people, so that anger no longer feels necessary.

We often become angry as a way of coping with these painful primary emotions, usually by avoiding them, and diverting our attention away from them by blaming other people for the problem. Merely saying the words “I feel hurt”, is actually one of the most powerful anger management strategies for many people. It can take courage, however, to express your feelings instead of masking them, and trying to protect your ego, by angering yourself instead. Of course, it prompts the question: “Why does that hurt your feelings so much?” And the answer will usually reveal that it hit a nerve and triggered a deeper anxiety, e.g., “I feel hurt by you using my toothbrush because to me it means that you don’t really respect me anymore.”

So you can start by using simpler versions of “I talk” and progress to more assertive ways of communicating, which propose a collaborative solution.

“I feel angry” (or “I feel hurt”) or whatever emotion precedes your anger.

“I feel hurt because you used my toothbrush” or “I feel hurt when you use my toothbrush because it means…”

“I feel upset when you use my toothbrush, so I would prefer it if we could agree to stick to only using our own.”

A number of research studies have actually been conducted on “I talk” (aka “I language”, “I statements”, or “I messages”), which show that it tends to promote less defensiveness, greater self-awareness, more ownership of emotions, and a healthier style of communication.

By careful use of the first-person pronoun, in other words, we can often change our emotional response, replacing anger with healthy concern, and also express ourselves in a more constructive and less threatening way. Simply by changing the words we use, we can train ourselves to look in the mirror, and become more self-aware of our emotions, and less angry, as a result.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 13, 2025

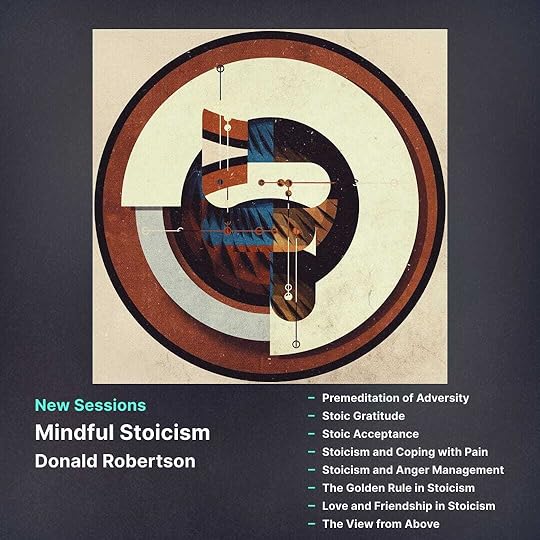

New Lessons for Mindful Stoicism

I am delighted to announce that eight brand new sessions for my audio course on Stoicism and Mindfulness in Sam Harris’ Waking Up app have now been released.

Artwork by Jonathan Conda

Artwork by Jonathan CondaThe folks at Waking Up are offering you a free 30 day trial of the app. (This offer is exclusively for new subscribers to the app)

Author and psychotherapist Donald Robertson mixes Stoic philosophy, modern psychology, and vivid historical anecdotes. The potent combination helps us challenge our limiting beliefs, clarify our core values, and find fulfillment in even our most difficult experiences.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“It's not easy to live consistently with wisdom, because our own fears and desires often lead us astray,” he says. But by illuminating today’s best therapeutic practices with the light of ancient Stoic teachings, “we discover a philosophy that allows us to build emotional resilience permanently, by making it an integral part of life.”

ContentsStoicism as a Philosophy of Life

What is Stoicism?

Values Clarification in Stoicism

Living in Accord with your Values

Stoic Mindfulness and Resilience

Cognitive Distancing

Postponing Rumination

Decatastrophizing

Premeditation of Adversity

Stoic Gratitude

Stoic Acceptance

Stoicism and Coping with Pain

Stoicism and Anger Management

The Golden Rule in Stoicism

Love and Friendship in Stoicism

The View from Above

Artwork by Jonathan Conda

Artwork by Jonathan CondaThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 11, 2025

CBT Imagery Exercise for Anger

In this article, I’ll briefly describe an imagery exercise that combines several cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques for dealing with anger. It’s loosely based on various common techniques such as Rational Emotive Imagery (REI) and Imaginal Exposure but tailored slightly for anger and incorporating some more recent (“third-wave CBT”) exercises.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

PreparationThe Target SituationThe most important thing is that you’ll need to identify a scene that makes you feel angry when you imagine it. Ideally that would be a recent event that you can relive in your memory, although it could be anything, as long as it does evoke anger. Often, instead of remembering a past event, you will want to anticipate an event that may happen in the near future in order to prepare yourself to cope without anger. You should rate the intensity of your anger using a scale from 0-10. (We call this a SUD scale, which stands for Subjective Units of Discomfort.)

Imagine the anger-provoking scene as if it’s happening right now, what you would see but also what you would feel, what you would be doing with your body, perhaps even what you would smell or taste. Don’t just picture it but really imagine that you are there as if it’s happening right now, and get your senses more involved. Focus on the most upsetting aspect of the scene – what really makes you angry? Note your initial SUD rating. Ideally, it would be roughly 6-9 at first (moderate or high intensity) but it’s possible to work with any rating.

Photo by engin akyurt on UnsplashAngry Thoughts and Beliefs

Photo by engin akyurt on UnsplashAngry Thoughts and BeliefsNext, you’ll want to identify the thoughts that make you angry. Sometimes that’s easy and other times it’s more tricky. Some techniques you can use are as follows:

Think of the event that makes you angry as a trigger and your anger as the response but ask yourself if there were any negative automatic thoughts that happened between them, i.e., after the trigger event happened but just before you began to get angry in response to it.

Notice all of the thoughts that went through your mind in relation to the anger and ask yourself which one makes you most angry when you focus your attention on it for a while.

Imagine that you can translate your anger into words and ask yourself: “What does it feel as if I’m telling myself?” or “What does it feel as if I’m thinking?”

If you notice questions associated with your anger, try turning them into statements, and perhaps asking yourself what would be so upsetting if that were true? For example, if you keep asking yourself “Why is this guy treating me this way?”, you may really be thinking “This guy should not treat me this way, and if he does that’s totally unacceptable.” In cognitive therapy, it’s easier to work on this statement rather than the question.

You may also find it helpful to use what we know about stereotypical angry beliefs as a guide. For example, when we’re angry with another person, we tend to have underlying beliefs such as (some but not necessarily all of) these:

Someone has done something they should not have done. (They’ve acted unfairly or unjustly, for example, or are guilty of wrongdoing.)

They are a terrible person. (They’re an idiot, they’re awful, they’re evil, they’re a crook, and so on.)

They deserve to be punished. (I ought to teach them a lesson, I hope they get what they deserve, etc.)

I can’t tolerate their actions. (This is unbearable, I can’t handle it, can’t stand it, can’t accept it, or can’t cope with it.)

I have to react aggressively. (Yelling or using violence, or otherwise showing my anger, is the only way I can get them to listen or do as I say.)

With mild irritation the thoughts might be similar but less extreme. For example, “My kids shouldn’t take so long to get dressed for school, it’s not acceptable, I have to raise my voice and snap at them to get them to hurry up.” Sometimes you may also be angry with yourself or with a situation, rather than with another person, in which case your angry beliefs may be slightly different. For example, “This situation is unfair”, or “I should not be so stupid”, etc.

Upsetting thoughts tend to form clusters, and can be seen as specific examples of more general underlying beliefs or attitudes. For example you might tell yourself “This guy’s being rude to me. Why can’t he talk to me properly? He’s not treating me right”, etc., if you have a strong underlying belief that says “People must respect me.” Many psychotherapists believe that the most disturbing beliefs are rigid “should” statements – the so-called Tyranny of the Shoulds. This type of thinking is particularly prominent in many cases of anger. Shoulds can actually be phrased as “must”, “have to”, “need to”, “got to”, etc., but they all express a rigid categorical imperative or demand, usually imposed on other people when we’re angry, but sometimes on ourselves or life in general.

For example, suppose I rigidly believe that “People should respect me”, “Life should be fair”, or “I should always get things right.” I’m creating, to put it bluntly, an obvious “recipe for neurosis”, because whenever those demands are not met, I’ll get upset. It’s almost as if I have an algorithm programmed in my brain that says “People must respect me because if they do not I will get angry.” To overcome your anger, you may need to change any programming of that sort.

The ProcessNow you’re ready to begin. Close your eyes and imagine yourself in the target situation, as if it is happening right now, and allow yourself to feel angry. Check your initial intensity rating: How upset do you feel from 0-10? Here’s a basic outline of the process with detailed information below:

Accept your angry feelings, view them with detachment, and let go of any struggle against them

Observe your angry thinking from a more objective point of view, e.g., by picturing it as writing you can observe from a distance

Optionally: Dispute your angry thinking by labelling cognitive biases that it contains and listing reasons for changing your perspective

Generate more rational alternative ways of thinking and rehearse asserting those beliefs in your imagination

Practice, practice, practice – until it becomes a habit

1. Emotional AcceptanceFirst, allow yourself, paradoxically, to stop trying to control your emotional pain or anger. Let go completely of any struggle against those unpleasant feelings or any desire to eliminate them or change them in any way. Relax into radical acceptance of the angry feelings. Feelings change naturally, they never remain static, so allow them to come and go freely, and evolve naturally. Think of this as allowing your brain to digest your feelings of anger, by experiencing them patiently and without resistance. In fact, you’re simply allowing natural emotional processing to take place, by giving yourself a bit more time than normal to experience your upsetting emotions. Notice where your anger is located in your body, and what sensations you feel. Notice things you hadn’t noticed before, such as slight changes in your breathing or in your facial expression. (Often people frown or stare, when angry, for example, and some people clench their jaw or their fists, often tensing their neck and shoulders – but everyone is different.)

Patiently accept your feelings, and sit with them for a while. Think of them as “over there” in your body. Think of consciousness as the space within which thoughts and feelings occur, and view them as occupying just one small corner of your awareness, as if those feelings are the size of a marble in the middle of a huge football stadium. Don’t avoid your feelings of anger, though, but radically accept them, and allow yourself to fully experience them.

After a while, check your intensity rating again, by asking yourself “What number do I have now?” You may find, ironically, that accepting your feelings in this way, causes them to reduce in intensity. In any case, letting go of any struggle against them is an important first step.

2. Cognitive DefusionNow turn your attention to one of the main beliefs that’s contributing to your anger. Again, you’re not trying to get rid of these thoughts or the beliefs underlying them but rather to accept them in order to experience them from a different perspective, with greater self-awareness, detachment, and objectivity.

For example, imagine you are looking through a big window at the target situation, so that you can take a marker pen and write your angry thought on the glass. Look at the belief, written on the window, but also look through the window at the scene. Think of this as representing the way you look at real events through the filter or lens of these beliefs. Now imagine the colour of the writing changing a few times, and the size of the writing, and the font or typeface of the letters. You’re just doing that to encourage your mind to spend more time than normal focusing on the image of the writing, so that you get used to experiencing the thought as an object “over there” before you, instead of becoming too absorbed in it. Another way of doing this, instead of the window, is to imagine your key angry beliefs written on big white labels, which you are sticking on objects or people in the target situation.

Again, take time to picture the words as if they are located “over there”, so that the experience becomes more familiar, and you get used to looking at them from this perspective. Notice how it changes the way you think and feel about those beliefs, when you view them with greater detachment and objectivity, in this way, almost as if you were observing someone else having those thoughts. You may find that you spontaneously begin to question your own angry beliefs, perhaps they seem mistaken, distorted, or even absurd to you, from this point of view.

After a while, check your intensity rating again, by asking yourself “What number do I have now?” You may find that getting used to viewing your main angry beliefs from this perspective reduces the intensity of your emotions, but it will also tend to increase the flexibility of your thinking, and therefore of your behaviour, and your ability to cope with the situation, especially over the longer-term.

3. Optional: Cognitive DisputationThe two preceding steps may suffice at first but, over time, you may find it helpful to also begin challenging or disputing your angry beliefs and attitudes. In my view, the best way to do this is to begin by noticing any errors or distortions in your thinking. Therapists make lists of common “thinking errors” to help clients do this but generally, as Aaron T. Beck pointed out, most errors fall into one of four basic categories:

Extreme thinking, i.e., you may be exaggerating (magnifying) or trivializing (minimizing) certain things. Are you blowing anything out of proportion or “catastrophizing” events unnecessarily? Are you underestimating your ability to tolerate or cope with the situation?

Selective thinking, i.e., you may be ignoring certain details, or focusing too much on others. Do you have tunnel vision for the aspects of the situation that make you angry? Are you guilty of selective attention or selective memory with regard to these events? Are you maybe not telling yourself the whole story?

Overgeneralization, i.e., talking as if something is “always” or “never” the case. Someone may indeed have done something wrong but do they always act that way? Do you never do anything wrong yourself?

Unfounded assumptions, i.e., jumping to conclusions. Are you “mind reading” people by falsely assuming you know what they’re thinking? Are you “fortune telling” by assuming you know something will definitely happen in the future when, in fact, it’s uncertain?

To realize that a thought contains an error, and consistently view it from that perspective, is to weaken the belief. The previous step of cognitive defusion will make it much easier for you to see the shortcomings of your own beliefs.

Another useful form of disputation is to ask yourself “How is that way of thinking working out for me?” or “How is it going to work out in the long run?” A more elaborate version of the same strategy consists in listing all the negative consequences of holding a particular angry belief. (If you like, you can weigh up the pros and cons of your angry thinking, although I think that’s better done afterwards rather than during the imagery exercise.) Another simple question I like to ask, from the Stoics, is this: “What does you more harm, your own anger or the thing you’re angry about?” (After the exercise, you may also want to use other forms of cognitive disputation, such as listing the evidence for and against your unhealthy beliefs.)

Again, rate the intensity of your emotion from 0-10 – what number do you have now? Focusing on the flaws in your reasoning is likely to weaken the intensity of your anger, but so is learning to view the situation from different perspectives, because it introduces more “cognitive flexibility”, and therefore less rigid thinking, and anger generally requires rigid thinking.

4. Generation of AlternativesI usually ask clients to do this during imagery techniques, even if we’ve only touched briefly on the cognitive disputation stage. Ask yourself: what would be a more rational way of thinking about the situation? Or, if you prefer, you can ask what would be a more realistic or more helpful thing to tell yourself – but keep it honest and rational. Another similar technique would be to ask yourself what a non-angry person, who is coping better with this situation, might say to themselves about it. It can take some time to find the right phrase but treat that as a process of trial and error learning. Experiment with different ways of looking at the situation, and explore new ways of thinking. Again, being flexible in your thinking is the opposite of anger, which requires rigid tunnel vision.

I also like to ask people, while they’re still imagining the situation, to repeat the rational alternative beliefs to themselves about three times in a calm and assertive tone of voice, in their mind. Or to repeat it as if they believe it 100% at an emotional level, and to imagine what their voice would sound like in that case. Then, one last time, rate the intensity of your anger, from 0-10 – what number do you have now?

PracticeMost people experience obvious improvements the first time they do this sort of exercise. However, repetition makes those changes stronger and more habitual. Ideally, you want to make a powerful mental association between the target situation and the new way of thinking and feeling. You can also think of the initial feelings of anger and the angry thoughts as triggers that you want, through association, to evoke your new rational perspective.

Keep working on one scene at a time. Once you feel certain it doesn’t bother you anymore you can move onto a different scene. Finish working on one situation, though, before you start working on another one. In my experience, if you repeat this sort of exercise for about 5-10 minutes each day, for about 1-2 weeks, you’ll normally be able to observe signs of improvement.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 6, 2025

If you want to appear wise then become wise...

CommentaryIf it should ever happen to you that you turn to externals with a view to pleasing someone, rest assured that you have lost your plan of life. Be content, therefore, in everything to be a philosopher, and if you wish also to be taken for one, show to yourself that you are one, and you will be able to accomplish it.

This passage clearly follows on from the theme of the previous one: what it means to become wise. If you ever find that you’ve become preoccupied with external things, such as wealth or reputation, because you’re trying to please someone else then realize that you have turned your back on philosophy. Just focus on the pursuit of wisdom.

February 4, 2025

Video: Stoicism, Socrates, and Modern Psychotherapy

Here’s a video of a recent conversation I had about ancient philosophy and psychotherapy with psychotherapist Alice McGurran, for the British therapy app Welldoing. I really enjoy speaking to other therapists. It’s what I started doing but I don’t get as much opportunity these days. So this was a chance to really focus on some of the questions that are of most interest to me personally.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

From the WebsiteDonald J. Robertson is a CBT psychotherapist who has been researching philosophy and applying it in his work for twenty years. He is one of the founding members of the non-profit organisation Modern Stoicism.

His latest book, How to Think Like Socrates, blends history, philosophy and psychology, providing a semi-fictionalised account of Socrates' life based closely on accounts found in ancient sources.

So, why Socrates? Robertson sees him as a forerunner to modern cognitive psychotherapy, exemplifying not only what it means to be mentally flexible and how to clarify your values, but also standing for the benefit of dialogue with another person – one way of describing therapy – as the best means of gathering wisdom and self-knowledge

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.