Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 9

January 23, 2025

Stoicism, Coaching, and Leadership

In this episode, I chat with Erick Cloward. Erick is an executive coach, based in Amsterdam, who helps leaders build more resilient teams and make better decisions. He is a former tech CTO and software developer. Erick started the Stoic Coffee Break podcast in 2018, to provide people with practical advice on applying Stoicism to their lives –- it now has more than 9 million downloads. He has his first book coming out on 4th February, from Adams Media, titled Stoicism 101: From Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus to the Role of Reason and Amor Fati, an Essential Primer on Stoic Philosophy.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow did you first become interested in Stoicism?

Misconceptions people have about Stoicism

Why Stoicism is important today

How did you get started doing your podcast and what have you learned from the experience?

What’s your book, Stoicism 101, about?

What aspects of Stoicism do you think are most relevant to executive coaching?

What can Stoicism tell us about leadership?

How Stoicism might help people to avoid getting so angry

Links

LinksThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 18, 2025

Are you ready for a multidisciplinary deep-dive into anger?

I get pretty excited about all of the events we organize through our nonprofit, the Plato’s Academy Centre. Our new event, however, is one that is especially important to me. Anger is the main topic that I plan to focus on this year. Why? Well, the short answer is that when I ask myself what the most important thing is that I could do before I die, the answer is something to do with what I call “the problem of anger.”

This event is free of charge, everyone is welcome to attend, and recordings will be available if you register in advance.

Anger is everywhere. Many politicians thrive on it — it’s like oxygen to them. (Angry people are easy to manipulate.) Social media is awash with rage-farming and something about certain platforms, such as Twitter, often seems especially to fuel angry exchanges and extremely hostile language. The Stoics, and other ancient philosophers, saw our own anger is one of the biggest threats to humanity. I believe they were correct and yet, in a sense, it’s become one of the most neglected emotions in modern philosophy and psychotherapy.

Earlier this year I put together a small informal group of psychologists to discuss opportunities for doing important psychological research on Stoicism and anger. I thought there would be 3-4 of us but our little group rapidly grew to consist of twenty researchers and clinicians, from around the world. (We don’t even have a name for the group yet, I just call it “Anger Squad”.) So before we knew it the question arose: What next? The answer seemed obvious to me: organize a conference!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I have divided this event into three main sections: philosophy, therapy, and research. We have presentations from experts explaining the approaches to anger found in Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, Plutarch, early Christianity, Greek myths and legends, and Aristotle. The intention is for the philosophers to communicate in plain English what the differences are between these approaches so that the audience and our therapists and researchers can take away practical insights, which might be worthy of future research!

We also have presentations from clinicians covering several major evidence-based approaches to cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), including Beck’s cognitive therapy, schema therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and also a successful CBT and Stoicism based training that’s been tested in UK prisons. We want the clinicians to highlight ideas that the audience can take away and use in their own lives but also areas of philosophical interest in relation to anger. We’re looking for ways in which ancient philosophy could complement modern evidence-based psychotherapy, and help us tackle the question of anger.

The researchers will then give an overview of some areas where we have important insights into the nature of anger. Followed by a multidisciplinary panel, with philosophers, clinicians, and researchers, discussing your questions and tackling some of the major questions that trouble us in relation to anger today. Why not join us? Everyone is welcome. This event will be of especial interest to therapists, philosophers and psychologists but absolutely everyone can benefit from learning more about the nature of anger and different perspectives on how to work with this powerful emotion.

Some questionsHere are some of the questions I would encourage you to think about in relation to the philosophy and psychology of anger…

What is the nature of anger? Are there qualitatively different types of anger, in the same way that we know there are different types of anxiety?

Do different types of anger respond to different forms of therapy and different self-help strategies?

What are the ingredients of anger? In particular, to what extent is our anger cognitive and shaped by angry thoughts and beliefs?

What are the predisposing factors that make someone vulnerable to problems with anger?

Are there healthy and unhealthy forms of anger or — like Buddhists and Stoics believe — is all anger unhealthy?

What exactly are the costs, or risks, associated with anger? What are the longer-term implications of anger, and what is its wider impact on different domains of our life?

What exactly are the benefits of anger and can they be achieved in better ways, without incurring the same costs?

Conventional CBT for anger is effective but could it potentially be improved?

Do Stoicism and other ancient philosophies potentially offer clues for ways in which modern therapists could help their clients to cope with anger?

This, like all our virtual conferences, is completely free of charge, although you’re welcome to donate an amount of your choosing to help us continue doing similar work in the future. Please share the link and encourage your friends to join us as well.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 16, 2025

Stoicism and Life Coaching

In this episode, I chat with Benny Voncken, a life coach, and the co-founder of the Via Stoica website and Podcast. He reached out to me saying he’d love to share his experience putting Stoic philosophy into practice because it greatly reduced his anxiety, worries, and helped him deal with problems such as anger and frustration.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

HighlightsHow did you become interested in Stoicism?

Tell us about your website and podcast.

Why do you think Stoicism is important today?

How do you see the value of Stoicism in relation to life coaching?

What are some ways Stoic ideas or techniques can help people?

What do you think Stoicism tells us about coping with worry and anxiety?

I’m very interested in anger, how do you think Stoicism might help people to avoid getting so angry?

What’s a good way for people to begin learning about Stoicism and applying it in their life?

Links

LinksThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 9, 2025

If you want to be a philosopher prepare to be ridiculed...

CommentaryIf you yearn for philosophy, prepare at once to be met with ridicule, to have many people jeer at you, and say, “Here he is again, turned philosopher all of a sudden,” and “Where do you suppose he got that high brow?” But do you not put on a high brow, and do you so hold fast to the things which to you seem best, as a man who has been assigned by God to this post; and remember that if you abide by the same principles, those who formerly used to laugh at you will later come to admire you, but if you are worsted by them, you will get the laugh on yourself twice.

Epictetus tends to portray becoming a philosopher in all or nothing terms. If you are serious about becoming a philosopher, a true lover of wisdom, you should assume that people are going to ridicule you for doing so. They’ll accuse you of being insincere, pretentious, and a phoney. You have to be ready to ignore them and do what seems right to you regardless, as though you’re answering a calling from God.

January 8, 2025

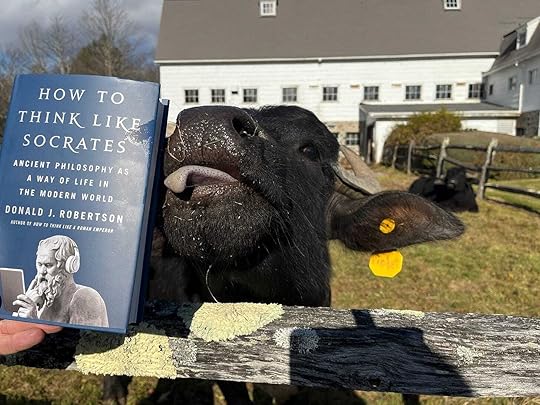

Read the Initial Reviews of "How to Think Like Socrates"

How to Think Like Socrates, my latest book, was released about six weeks ago in the US and some other regions. I wanted to thank all of you for your support, and especially for taking the time to review the book online.

Already, over 160 people have rated or reviewed it on Goodreads, where it currently has 4.16 stars. On Amazon, it is rated 4.4 stars from 44 reviews, and it has a 4.8 star rating on Audible, for the audiobook — which seems to be the most popular format.

We even got a shout out from Audible on Twitter:

Amazon’s new AI feature summarizes the content of reviews on their website as follows:

Customers praise the book for its writing quality, pacing, and profound insights. They find it enjoyable, educational, and easy to read. Readers say it's worth the money and worth the wait.

Barnes and Noble made it a Bookseller’s pick with the following recommendation:

A practical application of his philosophy to contemporary problems, this book makes the wisdom of Socrates more accessible than ever before.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Publisher’s Weekly gave it this review:

Robertson draws incisive links between modern psychotherapy and ancient philosophy, bringing Socratic dialogues to life through colorful narration and detail. It’s a creative look at the enduring relevance of an ancient thinker.

If you haven’t already done so, you can download our illustrated guide to How to Think Like Socrates using the link below:

A Guide To How To Think Like Socrates4.46MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload our illustrated PDF with information on key characters, events, and techniques from the book.DownloadThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 3, 2025

Now Available: Mindful Stoicism

Artwork by Jonathan Conda

Artwork by Jonathan CondaLast year, I was invited to design an audio course on Stoicism and Mindfulness for Sam Harris’ Waking Up app. I went to the d’Aragon studio in Montreal to record the lessons. I’m delighted to say that part one was published today, with the second part to follow in March. Waking Up have provided a special link so that you can enroll on the course and claim a free 30-day trial if you’re new to the app.

Author and psychotherapist Donald Robertson mixes Stoic philosophy, modern psychology, and vivid historical anecdotes. The potent combination helps us challenge our limiting beliefs, clarify our core values, and find fulfillment in even our most difficult experiences.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“It's not easy to live consistently with wisdom, because our own fears and desires often lead us astray,” he says. But by illuminating today’s best therapeutic practices with the light of ancient Stoic teachings, “we discover a philosophy that allows us to build emotional resilience permanently, by making it an integral part of life.”

Artwork by Jason ChatfieldOutline of Part One

Artwork by Jason ChatfieldOutline of Part OneStoicism as a Philosophy of Life

What is Stoicism?

Values Clarification in Stoicism

Living in Accord with your Values

Stoic Mindfulness and Resilience

Cognitive Distancing

Postponing Rumination

Decatastrophizing

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 2, 2025

Watch "Why Socrates Matters"

Watch the video of our recent symposium on the modern relevance of Socrates, hosted by Anya Leonard of Classical Wisdom.

Prof. Angie Hobbs, philosopher

Prof. Armand D’Angour, classicist

Donald Robertson, psychotherapist

Prof. Massimo Pigliucci, philosopher

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 31, 2024

Stoicism: The Bull and the Lion

In Tom Wolfe’s novel, A Man in Full (1998), two of the leading characters become enthusiastic followers of Epictetus’ Stoicism. They are inspired by his references to the image of a strong bull who naturally steps forward to protect the weaker members of the herd from attack by a lion. Indeed, one of the chapters entitled “The Bull and the Lion”, contains the following exchange:

“That’s fine,” said Charlie, “but how do you know what your character is? Let’s say there’s a crisis you’ve got to deal with. How do you know what you’re really made of?” “Epictetus talks about that,” said Conrad, “He says, how does a bull, when a lion’s coming after him, and he has to protect the whole herd – how does he know what powers he’s got? He knows because it has taken him a long time to become powerful. Like the bull, a man doesn’t become heroic all of a sudden, either. Epictetus says, ‘He must train through the winter and make ready.'” — Tom Wolfe, A Man in Full

Epictetus several times employs the image of a strong bull who protects the rest of the herd. However, the symbol of the bull as a leader was not unusual in the ancient world, and had been in use for many centuries. For example, we find it used by Homer to describe the Mycenaean king, Agamemnon:

As when a bull stands out among the herd, preeminent above the rest, for he is leader among the grazing cattle, so was Agamemnon made glorious on that day. — Iliad, 2.480–483

This symbolism is much older even than Homer’s works and appears to have originated in near eastern cultures, where the bull was an important religious symbol associated with kingship. One of the main Phoenician deities, e.g., was the Canaanite storm god, Baal, who was often symbolized by a bull.

Curiously, in Greek mythology, Zeus, a storm god like Baal, assumes the form of a bull in order to abduct Europa, a Phoenician princess, from the city of Tyre. Zeus takes Europa to Crete where she gives birth to a child who goes on to become King Minos, the founder of the Minoan civilization, which was, of course, steeped in the symbolism of the bull. This legend seems to evoke the idea of Greek civilization appropriating aspects of near eastern culture.

…observing one shared way of life and one kind of social order, like a herd that grazes together with equal right in a common pasture.

The Europa myth might also remind us of the origins of Stoicism itself, as Zeno, its founder, was a Phoenician, who found himself in Athens, a Greek city. There is some evidence that Zeno employed the metaphor of a herd of cattle to describe the ideal Stoic community in the Republic, which was quite possibly the founding text of Stoicism. For example, according to Plutarch:

Indeed, the much-admired Republic of Zeno, the one who founded the Stoic school of thought, comes down to this one main point: that we should not live divided according to cities or demes, each defined by our own separate laws, but instead, we should consider all humans to be our fellow-demesmen and citizens, observing one shared way of life and one kind of social order, like a herd that grazes together with equal right in a common pasture. Zeno wrote this, envisioning, as if in a dream, a certain model of civic order and the image of a philosophical commonwealth. — Plutarch, On the Fortune of Alexander, 329A-C

This suggests that Zeno may have introduced the metaphor of the ideal Stoic Republic as consisting of a herd of cattle led by a bull. Indeed, the early Stoic school itself was a small community perhaps intended to be modelled on this ideal to some extent, so Zeno himself, or the subsequent scholarchs of the school, may have been seen as analogous to the bull in this imagery.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Late Minoan bull statuette, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.The Bull in Roman Stoicism

Late Minoan bull statuette, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.The Bull in Roman StoicismTwo centuries later, in the Roman Republic, Cicero portrays the Stoic Cato employing the bull as a metaphor for leadership instincts in his account of Stoic Ethics:

Nature has given bulls the instinct to defend their calves against lions with immense passion and force. In the same way, those with great talent and the capacity for achievement, as is said of Hercules and Liber, have a natural inclination to help the human race. — De Finibus, Book III

Curiously, a few generations later, in the Roman Empire, Seneca also says something quite similar, perhaps shedding light on the original meaning of the metaphor in Stoicism:

But the earliest mortals and those of their descendants who pursued nature without being spoiled shared the same guide and law, being entrusted to the decisions of a superiors, since it is natural for inferior things to give way to more powerful ones. Take herds of dumb animals: either the biggest or the strongest creatures have command. It is not the bull inferior to his breeding but the one who surpasses the other males in size and muscle who goes before the herds; it is the tallest elephant who leads the troupe; among men, “the best” replaces “the biggest”. So the ruler used to be chosen for his intellect, and the greatest happiness among nations was enjoyed by those among whom only the superior man could be more powerful. A man can safely enjoy as much power as he wishes if he believes he only has power to act as he should. — Seneca, Letters, 90

Seneca also briefly employs this image in his play Phaedra, when he writes: “Goaded on by love, the bold bull undertakes battle for the whole herd.”

Shortly after this, we find some of the most intriguing Stoic references to this bull imagery in Epictetus. Although cattle in general are sometimes looked down upon in the Discourses, the bull is several times used by Epictetus as a metaphor for an exceptionally good man, i.e., the ideal Stoic wise man or Sage:

It was asked, How shall each of us perceive what belongs to his character? Whence, replied Epictetus, does a bull, when the lion approaches, alone recognize his own qualifications, and expose himself alone for the whole herd? It is evident that with the qualifications occurs, at the same time, the consciousness of being imbued with them. And in the same manner, whoever of us hath such qualifications will not be ignorant of them. But neither is a bull nor a gallant-spirited man formed all at once. We are to exercise, and qualify ourselves, and not to run rashly upon what doth not concern us. — Discourses, 1

Here one ought nobly to say, “I am he who ought to take care of mankind.” For it is not every little paltry heifer that dares resist the lion; but if the bull should come up, and resist him, would you say to him, “Who are you? What business is it of yours?” In every species, man, there is some one quality which by nature excels, – in oxen, in dogs, in bees, in horses. Do not say to whatever excels, “Who are you?” If you do, it will, somehow or other, find a voice to tell you, “I am like the purple thread in a garment. Do not expect me to be like the rest; nor find fault with my nature, which has distinguished me from others.” — Discourses, 3

You are a calf; when the lion appears, act accordingly, or you will suffer for it. You are a bull; come and fight; for that is incumbent on you and becomes you, and you can do it. — Discourses, 3

The bull is also clearly equated with the “good man” in the passage below, a synonym for the Sage, and the metaphor of a hunting dog is employed in a similar manner:

For who that is charged with such principles, but must perceive, too, his own powers, and strive to put them in practice. Not even a bull is ignorant of his own powers, when any wild beast approaches the herd, nor waits he for any one to encourage him; nor does a dog when he spies any game. And if I have the powers of a good man, shall I wait for you to qualify me for my own proper actions? — Discourses, 4

In another passage he employs a similar metaphor, equating the role of the bull with that of the queen bee:

But what have you to do with the concerns of others? For what are you? Are you the bull in the herd, or the queen of the bees? Show me such ensigns of empire as she has from nature. But if you are a drone, and arrogate to yourself the kingdom of the bees, do you not think that your fellow-citizens will drive you out, just as the bees do the drones? — Discourses, 3

Marcus Aurelius, who had read the Discourses, perhaps even the four books lost today, mentions a similar metaphor, which he extends to the ram who guards the flock of sheep:

ConclusionIf any have offended against thee, consider first: What is my relation to men, and that we are made for one another; and in another respect, I was made to be set over them, as a ram over the flock or a bull over the herd. — Meditations

The Stoics, as we have seen, were probably drawing upon symbolism that originated in early near eastern civilizations. The image of the bull as leader might seem straightforward but Epictetus, in particular, develops it by asking his students to contemplate how the bull knows that he is, unlike the calves and heifers, capable of defending the herd by tossing a lion on his horns. The answer is that he has learned his own strengths and weaknesses through trial and error, just as a boxer or wrestler knows approximately which opponents are a good match for him, based on his previous experience. He puts himself to the test repeatedly, and thereby forms a clear impression of his own capabilities. We must do this for ourselves, in order to know which challenges in life we are capable of meeting.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 24, 2024

Five Practical Tips from Socrates

I was recently invited to contribute an article on How to Think Like Socrates for The Next Big Idea Club. Below are my first four pieces of advice and a link to the original article where you can read the fifth and final tip. There’s also an audio recording, which I narrated on that web page, if you prefer to listen to the article.

The Next Big Idea: Socrates1. How to practice the Socratic Method.

The Next Big Idea: Socrates1. How to practice the Socratic Method.Socrates, despite being one of the most influential philosophers in history, wrote nothing. At least, that’s what people like to say. However, Plato, his most famous student, tells us that while in prison awaiting his execution, Socrates wrote poetry. More intriguingly, Epictetus, the famous Stoic philosopher who lived four centuries later, claimed that Socrates jotted down countless notes that were designed for his own self-improvement but never intended for publication. Another of his students describes how Socrates taught a young man to practice philosophy by means of a formal written exercise.

For this exercise, Socrates drew two columns, the first headed “Justice” and the second “Injustice.” His companion was invited to list examples of wrongdoing under the heading of injustice, such as theft and deceit. It’s often easier to understand our values if we begin by defining their opposites. However, the basic skill underlying the Socratic Method really comes into play in the next step. Socrates asked his friend to imagine any situations where the things he’d listed under Injustice might be placed under the heading of Justice. For instance, a general who seized the weapons of the enemy during a war might be said to be stealing, but perhaps that’s not unjust. Likewise, a father might be considered justified in concealing medicine in his sick child’s food despite this being a form of deceit. Socrates was skilled at coming up with these sorts of examples.

Training yourself to think of exceptions to rules and definitions can help you avoid applying them too rigidly. This skill is important because the advice and techniques we learn from self-help books are often of limited value. What’s good advice in one situation may become bad advice in another. Solutions that work well for some problems may backfire when applied to others. Wisdom consists of thinking for yourself by adapting rules to fit new situations. Socrates’ two-column technique only teaches one small part of his famous philosophical method, but it’s a great way to start thinking more flexibly and adaptively about life.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

2. Generate alternative perspectives.Epictetus said, “People are distressed not by events but by their opinions about events.” This was one of the main inspirations behind cognitive therapy, the leading form of modern evidence-based psychotherapy. The idea goes back to Socrates, a century before the Stoic school of philosophy was founded. Modern psychological research has confirmed that our beliefs shape our emotions more than we normally assume. By changing the way we think, we can change the way we feel.

“Socrates, at times, behaved rather like a modern-day cognitive therapist.”

An obstacle stands in the way. Some of our beliefs are so entrenched that we find it difficult to imagine ever viewing events differently. When we’re gripped by strong emotions, such as fear or anger, it may feel natural to view certain events as catastrophic or certain people as unbearable. Socrates, at times, behaved rather like a modern-day cognitive therapist. He would ask his friends whether they imagined that the events that upset them might be viewed differently by other people. What you see as a catastrophe, someone else might view as bad but only temporary, whereas a third might even look at it as an opportunity. By becoming aware that multiple alternative perspectives are conceivable, you can attune to the way your beliefs influence your emotions.

3. Separate your thoughts from external events.

3. Separate your thoughts from external events.Cognitive therapists say our beliefs are like colored lenses through which we look at the world. Suppose you’re wearing blue lenses, which color the world with sadness. There’s a difference between looking at the world through your sad, blue lenses and looking at them. This shift in perspective can be compared to observing your own biases as if you were observing someone else’s.

When we can distinguish between our thoughts and external reality, we experience two main benefits. The most obvious is that our emotions tend to be reduced in intensity. The second is more subtle but arguably even more valuable: We become better at exploring alternative ways of looking at problems. With this flexibility, we find creative solutions to improve how things work out in the long term.

Therapists today have fancy names for this, like cognitive distancing or defusion, but it basically means learning to separate beliefs from the things they refer to. It allows you to view your own thinking with greater objectivity and has been found especially helpful for emotional problems such as anxiety and depression. The simplest way to do this is by writing your thoughts down and observing them from a detached perspective. Another method is to tell yourself, “I notice right now that I am having the thought…” and then state the thought you were having as if you were putting it in quotation marks. You can also imagine that some thought or belief has been painted in big letters on a wall, picturing the color and shape of the letters or changing their appearance until you have a sense of the words being like external objects. Therapists may also ask their clients to repeat a troubling thought aloud rapidly for around thirty seconds or to say it more slowly, with longer pauses. It’s interesting to try worrying in slow motion!

These techniques allow us to experience a thought or belief with greater detachment by looking at our mental lenses rather than looking through them. You’re not avoiding the thought, and you can still discuss evidence for and against it. You’re just experiencing it from another perspective. I believe that Socrates gained this sort of detachment from his own beliefs by discussing them with his friends. He compared self-knowledge to an eye that sees itself, and the best way to achieve this, he thought, was by engaging in philosophical conversations where you view the other person as a mirror for the mind, in which you contemplate your thinking more objectively.

4. Illeism, meaning talking in the third person.

4. Illeism, meaning talking in the third person.When Socrates finished discussing philosophy with his friends, he would go home and continue the conversation with himself in private. He would imagine another Socrates interrogating him about his assumptions concerning wisdom, justice, and other virtues. Socrates appears to have been known for referring to himself as if he was another person. A similar technique, which involves talking about yourself using your name or third-person pronouns, is called Illeism. It is occasionally used in modern psychotherapy to help clients manage anxiety and other distressing emotions.

“We often seem better at giving other people advice than solving our own problems.”

The psychologist Igor Grossman heads a center that conducts research on the nature of wisdom at the University of Waterloo, in Canada. He was intrigued by a paradox: we often seem better at giving other people advice than solving our own problems. He and his colleagues carried out a variety of experiments and found that when people write about their problems in a journal using the third person, they exhibit more wisdom than when writing in the first person. He calls this method distanced reflection, and it can improve your ability to reason, especially about problems that normally evoke strong feelings.

Read the original article or listen to the audio recording on the website of The Next Big Idea Club.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 17, 2024

The Socratic Method at Christmas

Photo by Scott Rodgerson on Unsplash

Photo by Scott Rodgerson on Unsplash[This modified excerpt from my latest book How to Think Like Socrates, discusses ]

The Socratic Method is a process of thinking. Its constant refrain is “Yes but…”, because it happily seeks out one exception after another to our definitions, assumptions, and other verbal rules. It forces us to think for ourselves by continually placing in question our most important values in life, such as our goals for self-improvement.

Wisdom cannot be taught but, perhaps, it can be learned…

Socrates did not think books were useless. In fact, he was an avid reader, who frequently enjoyed quoting other writers. However, like the cryptic oracles of Apollo, we have to question what we read and learn from others and put it to the test by trying to identify exceptions, or situations where it no longer holds true. Even the pronouncement that no man was wiser than Socrates, and the imperative to know ourselves, need to be examined in this way to be properly understood. Wisdom cannot be taught but, perhaps, it can be learned – especially if we make the effort to examine our own lives, and the assumptions on which our actions are based.

You can start right now. Where should you begin? At the very end, of course. Imagine you are facing execution like Socrates, perhaps even having your life judged, and possibly condemned, by your peers in court. For the sake of argument, let’s assume your fate is sealed, and there’s no point trying to convince the jury to acquit you. Looking back on your life, what would matter to you the most? What, in other words, would you want your life to stand for? This is how we frame the question today during a process known as “values clarification”, used in cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Let’s go further. Suppose you’re raising the hemlock cup to your lips, as Socrates did, about to take the fatal sip that will close your eyes for eternity. Imagine that these are your last few moments. Pause and think of what appeared most important to you throughout life. If you’re not sure how to answer, use this as a clue – what did you spend most of your time doing? That’s a very simple and instructive question to ask. Time is our greatest asset, in a sense. In what did you actually invest your time, yesterday and the day before? How important do those activities really seem, as you imagine looking back on them from the end of your life?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The pursuit of wealth is easy to examine from this perspective. As the saying goes, you can’t take it with you. How valuable is a million dollars? How much good would it be doing in your bank account as you are on the verge of passing away? It’s too late to spend it, either wisely or foolishly. From this point of view, when time is up, it’s more obvious that money itself is of no intrinsic value. What matters, if anything, is the use we choose to make of it. Many of the things that appear valuable throughout life are of this nature. We store them up, hoping to use them one day, when we get around to it, but perhaps they’re of no real value unless they’re used wisely.

Fame likewise seems worth pursuing to many people. Today we quantify fame even more simply than we do wealth. Perhaps you have a million followers on social media. Imagine, on your deathbed, asking yourself: Did that alone make life worth living? Once again, perhaps fame, like wealth, is merely a means to an end. At most, it creates the opportunity to influence certain people. If you never actually used your reputation for anything good, though, what was the point of spending time acquiring it? What if this is true of most of the things that appear valuable to the majority of people? What if we are born into a society that perpetually confuses the appearance of value with real value?

How about the opposite of wealth and fame? Suppose your business has failed, and you’ve lost everything in a bankruptcy. Suppose your reputation has been ruined by slanderous gossip, and, like Socrates, you’re surrounded by people who hate you, without even knowing you. Sometimes life can be unfair. Imagine, once again, your last moments. How much do such things as poverty and ridicule really matter, as long as you are certain that you did what was right? How much did they matter to Socrates? How much did they matter to other individuals like him throughout history?

What about the pursuit of knowledge? That seems like a more noble goal to many people, than acquiring wealth and fame. Is all knowledge equally valuable, though? Could you die content, not knowing how many angels can dance on the head of a pin? Have anyone’s final words ever been: “I only wish I’d finished watching all the Friends DVDs, so that I know how the series ends!” What about knowing how to help people, through the study of science or medicine? Of what value is that, or any other knowledge, unless you put it into practice wisely?

During his trial, Socrates distanced himself from the earlier philosophers who had made claims about the nature of celestial bodies. He considered this futile speculation, and of little practical value. You see, toward the end it becomes more obvious that many things we imagined to be important were only of potential value. What matters is how we use them, before our time is up. Facing up to the prospect of our own death can shatter this illusion, and free us from the bonds of our misplaced values.

Fortunately, you do not need to be executed to find this out. Why? Because Socrates has already done it for you. By contemplating his life, and the lives of other men and women who are long dead, we get to see what sense their values make once their lives are over. Socrates, during his trial, is presented as a man who was willing to live in relative poverty, and risk making powerful enemies, in order to pursue his philosophical mission. He considered a certain type of wisdom to be immeasurably more important than things like wealth and reputation. We should ask ourselves, as he asked others, whether we have somehow been duped into “undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the lesser” throughout our lives. If our goal is to improve ourselves, he says, we should ask whether wisdom and excellence of character come from possessing such things as wealth and reputation, or vice versa.

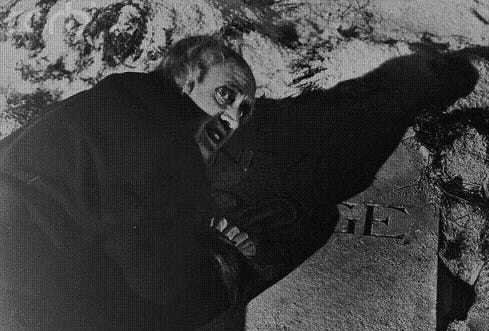

Many people, perhaps most people, never consider this perspective until it’s too late but sometimes, if we’re lucky, we get a second chance. In the Charles Dickens novel A Christmas Carol (1843), the miser, Ebeneezer Scrooge, has a moral epiphany, and decides to share his wealth with the poor, after a dream in which the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows him his own gravestone.

In 1888, Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, had a similar awakening, after reading, in a French newspaper, his own obituary, titled “The Merchant of Death Is Dead” – it had been published by mistake. Nobel was so shocked by this negative account of his legacy that he rewrote his will, dedicating 94% of his vast personal fortune to set up the famous Nobel Prizes for those conferring the greatest benefit on mankind in different branches of the sciences and arts.

By reading about the death of Socrates, and using your imagination, you gain an opportunity to skip ahead to the end of your own life. If you can do this, you may realize that many things which appear important, or which other people tell you are important, are not important in reality. Ask yourself the question (to borrow a Biblical phrase): quo vadis? – Where are you going? Socrates knew that we have to begin by eliminating our false convictions, to clear the way, before we can begin, with open minds, to learn the true goal of life. You can’t fill a jar with clean water if it’s already full of dirty water. We should examine our values by asking ourselves regularly whether the things we desire really make our lives worth living.

A Guide To How To Think Like Socrates4.46MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload our free illustrated guide to the characters, events, and practical techniques discussed in How to Think Like Socrates.DownloadWhere does it leave us, though? With an uncomfortable sense of uncertainty, perhaps, about the most important things in life. There is one glimmer of light. What if knowing how to examine our lives by asking these sorts of questions, turns out to be our goal? Socrates would later say that the greatest good for man, the purpose of life itself, is to converse daily about virtue, or the improvement of our own character, because “the unexamined life is not worth living.” After his trial, he reminded his friends to keep questioning themselves and others, including his own sons, in order to purge intellectual conceits, especially if they seemed to care more about wealth, or suchlike, than about wisdom and virtue. Philosophy, for him, was, first and foremost, a process for improving our character, by critically examining our deepest values.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.