Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 2

September 23, 2025

Welcome to the Neurotic Paradox!

Why do people continue to do things that are clearly not in their best interests? It can seem obvious, from the outside, when a friend’s behaviour is self-defeating. And yet they may continue very persistently to sabotage themselves. Ovid, the Roman poet, captured it well, in a famous piece of verse from his Metamorphoses:

Desire is persuading me one way,

reason another. I see the better course and I approve it,

but I follow the worse. — Metamorphoses, 7,19-21

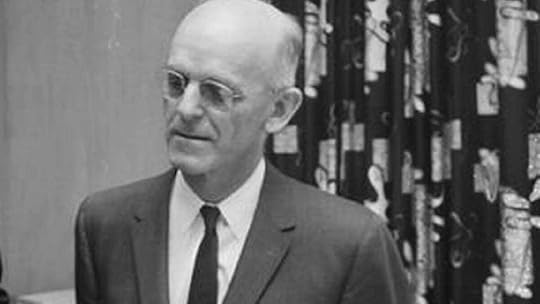

In 1948, O. Hobart Mowrer, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois, who would later become president of the American Psychological Association (APA), published an article titled ‘Learning theory and the neurotic paradox’, which attempted to explain this puzzling, but universally recognized, phenomenon.

Stated in its most general form, the neurotic paradox is this: How is it that behavior which is manifestly unrewarding and even self-defeating can persist over a long period of time, in persons who are not manifestly psychotic or mentally defective? From the standpoint of common sense and from the standpoint of much contemporary learning theory, such behavior is paradoxical in the extreme. — Mowrer, 1948, my italics

In other words, unless perhaps an individual has very severe cognitive impairment, we might expect them to learn from their experience and, eventually, stop doing things that are clearly making their life worse. But often they don’t. So what’s going on?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Mowrer proposed a simple clinical theory, which combined two different forms of behavioural psychology, which was once called “learning theory”. It’s known as the “two-factor theory” of neurosis. Despite its simplicity, Mowrer’s hypothesis has largely stood the test of time. (I’ll discuss some caveats and modifications at the end.)

Modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) combines ideas from cognitive and behavioural psychology, two rival traditions in the social sciences. It also combines both behavioural and cognitive approaches to treatment. Although many clinicians have forgotten about Mowrer’s original “two-factor” theory, it is actually the cornerstone of virtually all of the behavioural psychology models used in modern CBT.

Mowrer was right, basically. Like most theories that hit the nail on the head, his innovation ended up being taken for granted. It’s become the clinical equivalent of “common sense”, so much so that Mowrer is now seldom referenced or given the credit that he is due for his innovation. Yet his basic insight remains foundational. We are still in the grip of the Neurotic Paradox today.

Photo by Hasan Almasi on UnsplashThe Two-Factor Theory

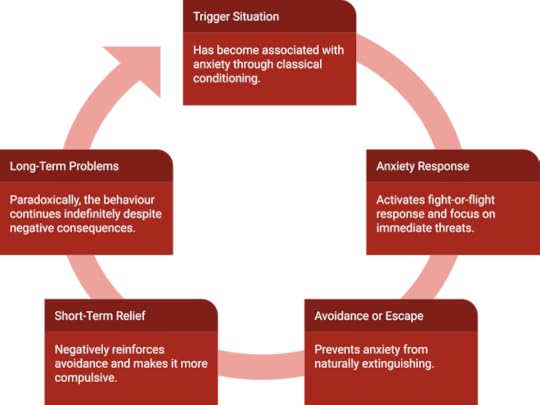

Photo by Hasan Almasi on UnsplashThe Two-Factor TheoryThis is how Mowrer explained the Neurotic Paradox, which had puzzled people since before even the time when Ovid was writing. It uses two well-established forms of conditioning or “learning” theory.

First Factor: Pavlovian (Classical) ConditioningIn plain English: We learn to feel irrational anxiety in response to things that were repeatedly associated, over time, with triggers that naturally cause anxiety. For instance, if every time a child tries to speak, they’re yelled at to keep quiet, they may eventually learn to associate feelings of anxiety with any efforts to speak in public. (In technical terms: through the repeated association of a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus, which triggers an unconditioned response, a conditioned stimulus-response reaction is established.)

This explains why we feel irrational anxiety. Over time, we build up an association between anxiety and certain triggers, or situations, which may no longer actually present any threat to us. It has become a habit to feel anxious, even though we’re no longer in danger. Pavlov trained his dogs to salivate whenever they heard a bell ring, by pairing the bell repeatedly with the presentation of food. Instead of salivating, their early childhood experiences can train humans to feel anxiety (or other feelings) involuntarily in response to certain cues or signals.

Let me also apply this to relationships. Someone who repeatedly watched their parents fight, as a child, may have been conditioned to feel intense anxiety whenever they perceive signs of conflict in a relationship. Later, in adult life, when a potential conflict arises in their own relationship, even if it’s mild and could be easily resolved, they have learned to respond with intense anxiety. This may appear “irrational” or out of proportion to the real situation because it’s not a “natural” response to a “real” threat. Rather, it’s a conditioned response to a conditioned stimulus that has been built up through habit and association, perhaps even without us being fully conscious of how it was learned.

The first factor explains why our anxiety can seem “neurotic” or “irrational” but it doesn’t explain why our behaviour would seem neurotic. In fact, conditioned anxiety would normally be expected to wear off over time, through a process technically referred to as “extinction” or “emotional habituation”. If, as kids, I punched you really hard on the shoulder every time I said the word “Surprise!”, after a while the word alone may have made you jump involuntarily. But eventually this anxiety reaction would wear off. You wouldn’t still expect to be jumping out of your skin every time you hear the word “Surprise!” twenty or thirty years later. That’s not how classical conditioning normally works — it usually wears off naturally unless something maintains it. So why does neurotic anxiety and behaviour, set up in our youth, persist so long into adult life, and perhaps even permanently?

Second Factor: Operant Conditioning

Second Factor: Operant ConditioningThe other major approach to learning theory is known as “operant conditioning”. To most people this is familiar as the process of “reward and punishment” that forms the basis, for instance, of training animals. Pavlov noticed that a dog can be conditioned to involuntarily salivate every time it hears a bell, if that has been repeatedly associated with the presentation of food (when the dog was hungry). Later psychologists observed that a dog, for instance, could be conditioned to raise its paw voluntarily every time a signal is given, if it is repeatedly rewarded for making approximations to performing this behaviour. Maybe it lifts its paw a little, and is rewarded with a treat, then a little more next time, and given a treat, and so on, until the desired behaviour has, step by step, been “shaped” through what is known as “positive reinforcement”.

We call it “positive” reinforcement when something happens that the dog likes, such as receiving a treat or a pat on the head. (That’s a simplification, reinforcement is technically anything that increases the probability of the behaviour, but for our purposes we can think of it as receiving a treat.) So far so good but there’s another form of reinforcement, which is often slightly more subtle and indirect, and shapes neurotic behaviour even more powerfully. It’s called “negative” reinforcement, not because it’s “bad” or “unpleasant”, but because it consists in removing or avoiding something we don’t like. (Negative reinforcement is therefore not to be confused with punishment, a very different concept.) You can think of it, crudely, as not a direct reward or treat but rather the sort of thing that brings about a feeling of relief. “Thank God that’s over!” Neuroses, or emotional problems, are built primarily on a foundation of negative reinforcement.

The icing on the cake of Mowrer’s theory was that once we have acquired neurotic anxiety through classical conditioning, we also end up behaving in neurotic ways that temporarily avoid or alleviate it. Suppose I have a fear of public speaking. I may feel an overwhelming urge to “avoid” ever getting into any situations where I’m expected to speak in public. If I do find myself, unexpectedly, the centre of attention, and expected to speak in public, I may do whatever I can to “escape” the situation as rapidly as possible — perhaps by making my excuses and dashing for the door. Of course, that’s not going to help me much in the long-run. It may lead to a variety of personal and interpersonal problems. So why do we do it?

Avoidance relieves anxiety in the short-term but maintains it in the long-term.

The biggest problem is that it will prevent the anxiety from ever extinguishing, or wearing off naturally. Avoidance relieves anxiety in the short-term but maintains it in the long-term. Avoidance is the world’s number one most popular coping strategy but it’s like constantly picking at a scab — every time you avoid an irrational fear, you keep the wound from healing. Worse, through constant negative reinforcement, our behaviour will not only become more likely but eventually it will become faster, less conscious, and more automatic. We’ll start to feel ourselves avoiding trigger situations more compulsively, and in more subtle ways. It will become increasingly hard for us to resist engaging in this behaviour because it has been powerfully reinforced countless times, over many years.

The core of the neurotic paradox is the simple fact that anxiety compels us to engage in avoidance behaviour, which maintains our irrational feelings. It’s a vicious cycle. The anxiety should normally wear off over time, without reinforcement. (Nothing catastrophic happens that would make us feel realistic anxiety.) The unhelpful behavior should normally fade away too, without reinforcement. (Nothing positive happens as a result of our avoidance.) However, the opposite happens, and we’re caught in a trap, going round in circles. The anxiety compels us to act in a way that maintains it, and the behaviour is negatively reinforced, because it relieves the anxiety.

If I avoid public speaking situations, I’ll never get over my anxiety. Moreover, my urge to avoid them will bring temporary relief, which will eventually make make me, in layman’s terms, “addicted” to avoidance. Avoidance feels good, or at least it feels better than anxiety. Over the years, this will make our neurotic behaviour more and more compulsive, until we’ll find ourselves struggling to overcome it, even though, like Ovid, we may realize it’s doing us more harm than good in the long run. The long-term consequences of our actions are not usually powerful reinforcement. The relief from anxiety that avoidance brings is virtually immediate, and extremely powerful, so that it overrides our concern about the longer-term consequences of our behaviour.

Okay, so it’s a simple theory, but there are a couple of moving parts here, so let’s apply it again to our previous example. Someone who repeatedly watched their parents fight, as a child, let’s suppose has learned to associate anxiety with perceived signs of conflict. It’s an over-generalization that no longer helps them, and it should just wear off normally, but it won’t if they engage in avoidance, and avoidance can take many subtle forms. Suppose they discovered, as a child, that “keeping the peace” and “people pleasing” can help them to avoid the threat of conflict, and thereby relieve their own anxiety. Those behaviours will probably, over the years, become deeply-ingrained and compulsive.

As an outside observer, it may be glaringly obvious that, for instance, this individual is remaining too long in an unrewarding job or an unhealthy, or even abusive, relationship. Why can’t they see that? Because their submissive people-pleasing coping strategy has been powerfully negatively reinforced, so many times, that it’s become compulsive and maybe even part of their personality. The long-term benefits of leaving and finding a new job or relationship seem vague to them, whereas the anxiety-relief that comes from behaving submissively is instantaneous and overwhelming. They sacrifice their long-term happiness, for short-term relief from anxiety, because that’s how conditioning works.

Even worse, the more anxiety they feel, the harder it will be for them to focus on the long-term benefits of behaving in an autonomous and assertive manner. When we are anxious, our brain goes into an emergency mode, in which it largely shuts down reasoning in terms of the longer-term, and focuses on survival in the present moment. So we reach for avoidance as the best solution, although our lack of assertiveness traps us even deeper in the situation that’s causing us problems.

Orval Hobart Mowrer (1907 — 1982)The Solution

Orval Hobart Mowrer (1907 — 1982)The SolutionIf the Neurotic Paradox sounds pretty bleak, the good news is that Mowrer’s theory offers us a road to salvation because it points to a very clear solution. The beauty of this theory is that it applies to countless different forms of avoidance, and different forms of maladaptive behaviour. Sometimes that can make it hard to fully comprehend the implications, because they’re so pervasive across different situations. So I’ll give two different examples for comparison.

Suppose you are afraid of public speaking, as we described above. The solution would be to abandon the avoidance behaviour and, instead, to face your fears consistently. That’s not easy to do but it’s the foundation of what we now call Exposure Therapy, perhaps the most robustly-established treatment in the entire field of research on psychotherapy. By facing our fears patiently, and enduring the anxiety, it will eventually extinguish, as long as we completely abandon the avoidance behaviour. Although that is difficult at first, if we can resist the urge to run out of the door, because the anxiety abates, the compulsion to avoid the situation will also eventually cease too, as it’s no longer being maintained by anxiety relief or “negative reinforcement”.

Now let’s turn to our slightly more subtle example. Suppose someone has learned to feel anxious about interpersonal conflict, and so they avoid it in more subtle ways, such as “people pleasing” and neurotic agreeableness. If they can learn to accept the anxious feelings rather than trying to avoid or control them, and engage in assertive behaviour regardless, over time, their anxiety will naturally abate. They will learn that nothing catastrophic happens and that even if their partner is upset, they can cope with it, if they approach it in the right way. As the anxiety reduces, the negative reinforcement that maintains the compulsive people-pleasing will be extinguished. When this happens, although it may seem very simplistic to phrase it this way, people will often say things like “I just realized, it wasn’t worth it anymore”, as their underlying incentive to engage in dysfunctional behaviour has gone.

ConclusionMowrer’s two-factor theory was, in my opinion, a stroke of clinical genius. It is, however, nearly eighty years old. It’s remarkable that it still retains so much explanatory power, and plays a role in even very recent cognitive-behavioural conceptualization models. Avoidance can take many forms, from obvious behavioural avoidance (e.g., “running out of the room”) to subtle avoidance such as avoiding eye-contact, avoiding talking about certain subjects, distracting yourself, “positive thinking”, superstitions, and any number of other safety-seeking strategies.

Although it’s usually applied to anxiety disorders, the Two-Factor theory also applies to other emotional problems, including anger and depression. Behavioural psychologists have understood depression largely as a deficit of positive reinforcement but we now know that it is also maintained by avoidance and therefore negative reinforcement, not unlike anxiety. For example, a depressed person may try to avoid unpleasant feelings such as boredom and sadness by distracting themselves from them, using drugs, having sex, watching television, playing games, and so on. This behaviour can start to become compulsive, in just the way that Mowrer described. Anger itself can be seen as a “secondary emotion”, which arises as an attempt to cope with anxiety, or emotional pain, and thereby itself becomes negatively reinforced, more or less as the Two-Factor theory describes.

We now realize that many other factors can maintain problems such as public speaking anxiety or people-pleasing behaviour, and so on. For instance, many forms of anxiety, such as fear of snakes and spiders, appear to be innate and are probably due more to lack of exposure than classical conditioning — but this is probably a minor distinction. Most notably, our cognitions — our thoughts and beliefs — have a powerful influence on our feelings and actions in anxious situations. Nevertheless, there’s an interplay between the behavioural conditioning processes described by Mowrer and the cognitive processes that are emphasized in modern cognitive therapy, such that most clinicians tend to work on both levels at once, or at least to alternate between them.

The benefit of Mowrer’s theory is that it really highlights the self-defeating (paradoxical) nature of our behaviour, and drawing attention to this is the first step toward changing it. The Two-Factor Theory makes it clear that the solution consists primarily in reversing our avoidance behaviour, and facing our fears, consistently enough for the anxiety to be allowed to wear off naturally. But it also helps to explain why people are so reluctant to do this in the first place: because anxiety is unpleasant and our avoidance has become such a strong habit that it’s somewhat compulsive. So drop your avoidance, and safety-seeking, face your fears, persist, go through the fire of anxiety, and you’ll emerge from the other side eventually, at the promised land of better long-term consequences for your own mental and physical health, and your relationships.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 18, 2025

Watch our Stoicism & Anger Video

Thank you , , , , , and many others for tuning into my live video with and ! Join me for my next live video in the app.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

The Inner Fortress: Military Resilience and Stoic Philosophy

In this episode, my guest is Carlos Garcia. Carlos is the Co-Founder and CEO of True Progress Lab, a coaching company that operates on the motto 'Get Calm. Get Bold. Get After It'. He is also a Major and Judge Advocate in the U.S. Army Reserve, and an Army-certified Master Resilience Trainer.

HighlightsCarlos, you have a fascinating background—an attorney, a Major and Judge Advocate in the U.S. Army Reserve, and a high-performance coach. How did your experiences in these high-stakes environments lead you to focus on resilience and coaching?

You're an Army-certified Master Resilience Trainer. What are the core principles the military teaches for handling adversity?

Are there overlaps with ancient Stoic philosophy?

How do you think the army’s resilience training could be improved?

You mentioned that reading about Stoicism and Marcus Aurelius has been "instrumental" in shaping your philosophy. Which of his ideas resonated most deeply with you, and how do you see them applying to a modern leader or soldier?

Your flagship course is called The Inner Fortress, can you tell us a bit about that?

A key focus of your coaching is overcoming FOPO, or the "fear of people's opinions". Why do you find this specific fear is such a powerful inhibitor for the successful professionals you work with?

You use a unique blend of Stoic philosophy and exposure therapy to help clients. Could you walk us through how you combine an ancient philosophy with a modern therapeutic technique to help someone act more boldly?

Finally, based on your experience, what do you think are some of the most helpful pieces of advice you can pass on to our listeners?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Links

LinksWeb: trueprogresslab.com

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Substack Live: You are invited to "Stoicism and Anger"!

NB: This event was postponed due to technical problems but will take place later today.

How do the Stoics conceptualize anger? Is there such a thing as healthy anger? And what do Marcus Aurelius and Seneca have to say about it? Use your mobile device to join us at 5pm eastern time today for a free discussion on Substack Live. Everyone is welcome!

Hosted by The Stoa Letter, you will need to use the Substack app on your mobile device to join this live event.

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

The Stoa LetterBecome more Stoic. Build resilience and virtue with ancient philosophy. By Caleb

The Stoa LetterBecome more Stoic. Build resilience and virtue with ancient philosophy. By CalebStoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 16, 2025

Could Jordan Peterson be the Messiah?

In 2018, an old friend, who’s an author and editor, hired me to read and review a series of books for a self-improvement website. Some of them were books on Stoicism. One of them was Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, an instant bestseller, which had been published only a few months earlier. I didn’t know very much about the author, except that he was a professor of clinical psychology at Toronto University — I also lived in Toronto at the time. I’d never come across his work before in a clinical context, although I’d heard about his videos, and the controversy surrounding some of his comments regarding Canada’s Bill C-16.

I expected that he would probably draw upon evidence-based clinical practice in psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and modern research on psychopathology, and adapt recent scientific findings for use as a form of self-improvement. That’s often what professors of clinical psychologists do when they write self-help books. In fact, I was genuinely surprised to find that there was no mention of CBT anywhere in the book and little or no use of relevant psychological research. There are long passages of what I would perhaps describe as some form of Jungian mystical theology, discussing, for example, the symbolism of the snake in the Garden of Eden. I enjoyed it, to some extent, but nevertheless I found it difficult to imagine that the majority of his readers were really looking for Biblical exegesis.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

One of the things that struck me most about the book, though, was the way it opened. In the years since it came out, I’ve never come across any mention of the unusual way in which Peterson sets the stage for his 12 Rules. When it’s come up in conversation, and I tell people what I recall reading, they often look quite taken aback and say they can’t believe that’s what he says. So I would pull up the book on my mobile phone (thanks to the Kindle app!) and let them read the opening pages for themselves. And then they would say something like: “Oh my God! He really does say that! I had no idea.” Even those who have read the book seem, invariably, to have skimmed this part without really noticing what they just read.

It doesn’t take long just to quote the relevant passages verbatim so I thought it might be useful, for those who don’t have the book, to read what Peterson actually says at the start of 12 Rules. Before getting to that, though, I think it’s helpful to provide some more context by reading what’s said in the Foreword that precedes it.

Part 1: Peterson as Moses

Part 1: Peterson as MosesThe Foreword is written by the psychoanalyst, Norman Doidge. He begins it by unabashedly comparing Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules to Moses’ Ten Commandments. He doesn’t just do this fleetingly, but spends about 500 words on the comparison, in order to set the stage for the book. He concludes:

One neat thing about the Bible story [of Moses] is that it doesn’t simply list its rules, as lawyers or legislators or administrators might; it embeds them [the Ten Commandments] in a dramatic tale that illustrates why we need them, thereby making them easier to understand. Similarly, in this book Professor Peterson doesn’t just propose his twelve rules, he tells stories, too, bringing to bear his knowledge of many fields as he illustrates and explains why the best rules do not ultimately restrict us but instead facilitate our goals and make for fuller, freer lives.

To my surprise, Doidge is emphatic about urging Peterson’s readers to interpret his rules for living not in a flexible but in a “rigid” (his word) manner: “After all,” he says, “God didn’t give Moses ‘The Ten Suggestions,’ he gave Commandments” because, as he puts it, “without rules we quickly become slaves to our passions.” Freedom, paradoxically, comes from rigid rule-governed behaviour — according to this book.

That, in a nutshell, runs counter to most modern research in psychotherapy, which tends to converge on the problematic nature of rigid thinking, rigid rule following, and rigid styles of coping, and to find evidence for the benefits of more flexible and adaptive ways of thinking and behaving. (You might also classify this as the commonsense view, as most people probably assume that flexible rules of life tend to be healthier and more adaptive than highly rigid ones.) Doidge, however, swimming against this scientific current, makes it clear that he considers Peterson to have written a book endorsing the value of rigid rule-following. (I’m not kidding; this is what he says.) Also, the “Commandments”, as Doidge puts it, are, of course, Peterson’s not yours — you’re to follow the 12 Rules as if they were being brought down from Mount Sinai by Moses. They’re not rules of living that you’ve discovered or invented yourself.

Doidge explains that: “I saw him [Peterson] grow, from the remarkable person he was, into someone even more able and assured—through living by these rules.” He attributes the “extraordinary response” to Peterson’s YouTube videos to a combination of his personality (or “charisma” as he puts it) and what he describes as the “hunger among many younger people for rules”, such as the simple pieces of life advice being laid out for them by Peterson. Just like Moses, Peterson, according to his friend Doidge, is a kind of prophet, whose authority we should unconditionally trust if we wish to be saved from our own ignorance and folly. We all have, as he puts it, a “deep unarticulated need” for rules and structure, and we are naturally looking for a father figure who can alleviate our confusion and suffering by simply telling us not only what to do but also what to think — we are all in deep spiritual crisis and desperately need Jordan Peterson to give us his “Commandments”, in other words, so that he can save us from ourselves.

At first, I though perhaps I’d misunderstood. But it’s not just a slip when Doidge speaks about Peterson’s rules being meant in a rigid sense like divine commandments etched in stone. It’s a message he hammers home repeatedly…

So why not call this a book of “guidelines,” a far more relaxed, user-friendly and less rigid sounding term than “rules”? Because these really are rules. And the foremost rule is that you must take responsibility for your own life. Period.

When I first read that, I felt certain he was about to note the obvious contradiction and that he would cleverly explain it to be some sort of subtle paradox. The number one rule is that you must take responsibility for your own life, and make your own decisions. That’s going to be achieved not by learning to think for yourself, and, for instance, adapting other people’s rules to meet the needs of your own challenges in life. Rather, the goal seems to be to strictly adhere to the rules written down by an authority figure who can be trusted because they’re wiser than you are. I was genuinely surprised to discover that neither Doidge nor, presumably, Peterson thought there was anything odd about this claim. They appear simply not to have noticed the irony in saying that we should take responsibility for our own lives by “rigidly” adhering to the “commandments” provided by an authority figure. Slavish devotion to the morality of the herd is something we are to view as bad whereas, it seems, equally slavish devotion to the rules of a lone authority figure is, somehow, something good.

As I read, I began to wonder whether I’d ever before read a Foreword to a book by a psychologist which portrays the author in these sort of grandiose terms. It seemed very peculiar to me that Doidge, a psychoanalyst by trade, didn’t think to question his own, pretty explicit, need not only to set Peterson up on a pedestal as an idealized father figure but even, for good measure, to compare him to the Biblical prophet Moses. I wondered if perhaps it was all just carelessness — a mere façon de parler. Sure, perhaps it came across at times as though he was viewing Peterson as some kind of idealized guru or saviour — and it maybe even felt a little bit cultish — but that can’t have been his intention.

I was hoping the Foreword would change tack eventually, and make it clear that, of course Doidge didn’t simply want us to view Peterson as our “daddy” and willingly subjugate ourselves to his rule. The tone seemed uncomfortably submissive to authority, in a way that appeared very out of place in a modern self-help book, but it might be leading somewhere else. However, its concluding sentence will, I think, leave many readers feeling equally perplexed:

And perhaps because, as unfamiliar and strange as it sounds, in the deepest part of our psyche, we all want to be judged.

Now, just a minute, surely he cannot mean that we all unconsciously desire to be judged by Jordan Peterson? He was definitely talking about Peterson but perhaps nevertheless he did mean “judged by God”? I would hope so, even though agnostics and atheists might still have a hard time with that notion being an underlying theme of 12 Rules. In any case, it seemed like a very peculiar note to leave us on, as he handed us over to Peterson.

I found these aspects of the Foreword so jarring, in fact, that I made a mental attempt to set the whole thing aside, and pretend to myself that I hadn’t read it. I didn’t want it to color my reading of the rest of the book. So I told myself that he probably just didn’t realize how grandiose it sounded to compare the 12 Rules of Jordan Peterson, unironically, to the Ten Commandments of Moses. I remember thinking to myself “There’s no way Peterson is going to go along with this and make himself out to be some sort of Messiah figure — no professor of clinical psychology would do that because it would just come across like he was suffering from delusions of grandeur.” So I began reading what Peterson himself had written, assuming that he would appear in an academic or clinical role, rather than as a Biblical prophet, and hopefully come across in a more level-headed sort of way…

Peterson has not shied away from controversy

Peterson has not shied away from controversy Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Part 2: Peterson as ChristHaving been compared to Moses in the Foreword, Peterson opens the book by now comparing himself to Christ. In what he calls the Overture to the book, he says that he has learned to pay attention to his dreams, from his training in clinical psychology. (Presumably he’s alluding to Jungian analytic psychology, which is over a century old now, because this sort of dream interpretation is not a standard component of modern evidence-based psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy.) He clearly places great importance on these dreams and states that he interprets them primarily in terms of Christian symbolism, that being the tradition with which he is most familiar. Peterson’s Overture centres on one dream in particular.

I dreamt one night during this period that I was suspended in mid-air, clinging to a chandelier, many storeys above the ground, directly under the dome of a massive cathedral. The people on the floor below were distant and tiny. There was a great expanse between me and any wall—and even the peak of the dome itself.

The intersection of the nave and transept in Gothic cathedrals is known as the “crossing” and, as Peterson recognizes, it is considered the architectural heart of the building, and a symbol of the crucifixion. He therefore adds:

I knew that cathedrals were constructed in the shape of a cross, and that the point under the dome was the centre of the cross.

Peterson, in other words, experienced a mystical vision in which he saw himself in the position of Jesus Christ, suspended from the centre of a cross, which, in this case, forms the ceiling of a cosmic cathedral. He soon makes that crystal clear despite, for some reason, initially phrasing it in a roundabout way.

Peterson goes on to refer to the fact that by being suspended from this cross he is forced to share in the suffering of Christ — although he’s speaking, of course, not about the physical pain of crucifixion but some form of spiritual or psychological anguish.

I knew that the cross was simultaneously, the point of greatest suffering, the point of death and transformation, and the symbolic centre of the world.

He is also at pains to emphasize that he found himself, in his dream or vision, swapping places with Christ unwillingly. Peterson is a reluctant messiah.

That was not somewhere I wanted to be. I managed to get down, out of the heights—out of the symbolic sky—back to safe, familiar, anonymous ground. I don’t know how. Then, still in my dream, I returned to my bedroom and my bed and tried to return to sleep and the peace of unconsciousness.

Nevertheless, Peterson tells us, he was forced back onto the cross again, in order, like it or not, to occupy the role of Christ at the centre of the cathedral, and, indeed, the centre of the universe.

As I relaxed, however, I could feel my body transported. A great wind was dissolving me, preparing to propel me back to the cathedral, to place me once again at that central point. There was no escape. It was a true nightmare.

When I first read this, I got the impression that Peterson had in mind what has become known as the Culture Wars, when he referred to the “great wind” that kept forcing him back into the position of becoming a reluctant Messiah. I’m not sure if that was his intention or not but it seemed natural to me to read his words that way. In any case, he proceeds to interpret his vision of himself on the cross, and to tell us what it meant to him personally.

Charles Stanley Peach, Plan of a Church Constructed on Divine Principles, 1910Part 3: What sort of Messiah is Peterson?

Charles Stanley Peach, Plan of a Church Constructed on Divine Principles, 1910Part 3: What sort of Messiah is Peterson?The interpretation Peterson gives, which he says took him several months to arrive at, is that the centre of “Being” is occupied by the individual. He was being forced to accept that transformation requires a special kind of suffering that comes from tearing oneself away from the moral doctrines of “the group” in order to find meaning elsewhere, by embracing a kind of radical individualism.

The centre is marked by the cross, as X marks the spot. Existence at that cross is suffering and transformation—and that fact, above all, needs to be voluntarily accepted. It is possible to transcend slavish adherence to the group and its doctrines and, simultaneously, to avoid the pitfalls of its opposite extreme, nihilism. It is possible, instead, to find sufficient meaning in individual consciousness and experience.

The notion that one’s individuality is the absolute centre of Being and infinitely more important than “the group”, or the rest of mankind, struck me, at first glance, as the complete opposite of Christianity. (It’s also a very modern Western concept and one that’s usually alien to, or a minority view, in ancient and non-Western cultures.) At face value anyway, Jesus typically seems to have emphasized that the Christian virtues consist in humility and brotherly love, not this sort of radical elevation of the self. At least, those are the values I remember being taught at Sunday School, and which seem to be emphasized in New Testament passages such as the following:

Jesus called them together and said, 'You know that those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many. — Mark 10:42-45

Peterson seemed to me to be turning “putting yourself first” into a religion, by framing it in Christian language and symbolism. Perhaps there’s a subtle way of interpreting what he says about embracing individuality and “transcending slavish adherence to the group” that overcomes the fact that it seems, on its face, to be the polar opposite of “whoever wants to be first must be the slave of all.” At first blush, this appeared to me to be the antithesis of Christian ethics, and an obvious paradox that I expected Peterson would surely go on to explain — but he does not.

Peterson’s deam unironically replaces the ideal of Christ with Nietzsche’s Antichrist.

I’m not a Christian, and I don’t share some of their traditional values. However, Christians in the New Testament certainly appear to have spoken as if they believed a form of self-denial, and service to others, not self-aggrandizing individualism, was the road to spiritual awakening and salvation.

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. — Philippians 2:3-8:

In fact, it sounded to me as though Peterson had borrowed a lot more from Nietzsche than from the New Testament. Nietzsche, the author of a work titled The Antichrist, rejected Christianity as what he called “slave morality”. In the preface to The Antichrist, he wrote, for instance, “One must make one’s self superior to humanity, in power, in loftiness of soul,—in contempt.” As the name implies, Nietzsche was proposing a deliberate inversion of Christian values. Peterson’s deam unironically replaces the ideal of Christ with Nietzsche’s Antichrist. It’s Christianity for people who hate Christianity — or so it seemed to me.

In Christianity, Jesus is the Messiah, in Nietzsche’s philosophy our salvation lies in the Ubermensch or “Superman”, a hypothetical ideal derived from our own creative values — not a real person. In Peterson’s vision, however, both the Christian Messiah and Nietzschean Superman appear to have been replaced by the image of Peterson himself, dangling from some sort of metaphysical crucifix, at the very centre of existence — assuming the position of Christ while echoing the doctrines of Nietzsche’s Antichrist.

Peterson has read Nietzsche, and is influenced by him in some ways. I’m not sure he realizes that Nietzsche, in turn, was influenced by Plato albeit in a deeply paradoxical manner. Nietzsche sounds not so much like Socrates, Plato’s hero, but, often, more like the Sophists, particularly Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic and Gorgias and Callicles in the Gorgias. Peterson, perhaps because of the indirect influence upon him of these characters, via Nietzsche, ends up sounding at times almost exactly like an ancient Greek Sophist. That’s not necessarily an insult, although the word has a very negative connotation today. Although the Sophists are, in a sense, typically the “bad guys” or “losers”, in Plato’s dialogues, Plato clearly admired them in some regards, and took them seriously as intellectuals.

Peterson interprets the message of his dream as a call to “transcend slavish adherence to the group and its doctrines” by embracing what he describes as “the elevation and development of the individual”.

My dream placed me at the centre of Being itself, and there was no escape. […] I came to a more complete, personal realization of what the great stories of the past continually insist upon: the centre is occupied by the individual. […] How could the world be freed from the terrible dilemma of conflict, on the one hand, and psychological and social dissolution, on the other? The answer was this: through the elevation and development of the individual, and through the willingness of everyone to shoulder the burden of Being and to take the heroic path.

Throughout 12 Rules, Peterson returns to these two overarching themes:

The moral and spiritual “centre is occupied by the individual” — he’s advocating for an unabashedly self-centred ethic in other words.

We should arrive at a new set of values which “transcend slavish adherence to the group and its doctrines” — altruism, in other words, is viewed as a form of weakness or subordination.

These assumptions permeate the rest of the book, where they are elaborated upon, albeit in a fragmentary and sometimes inconsistent manner. At this point, it’s worth pausing to note that most psychologists would take someone describing how they emphatically see themselves as being the centre of the universe as a textbook example of unhealthy narcissism. In cognitive therapy, for example, it would often be evidence of an early maladaptive schema (EMS) of “Grandiosity/Entitlement” and “Self-Aggrandizing” as a dysfunctional emotional coping strategy. It’s not typically how healthy individuals describe themselves because it clearly indicates a profound cognitive bias (aka “egocentric bias”). Assuming you’re (quite literally) the centre of the universe is not a lens through which most people would normally recommend viewing the world. And, moreover, none of us want to live in a world populated entirely by narcissists.

In any case, we should be fundamentally self-centred, he thinks, but dominance hierarchies, he says, are real and rooted in biological reality. It’s a dog-eat-dog world and every man for himself, etc. What he doesn’t say, therefore, is that this way of thinking divides society in the biologically “weaker” and “stronger” classes, and pits them against one another. So you better hope you’re one of the “strong” because their self-centred and individualistic desires are bound to trump yours. The alternative, of course, would be to work together with everyone else to create a harmonious society where all of our interests are respected, insofar as possible. That’s more akin to the Stoic and Christian ideal, for instance, whereas Peterson seems to think it’s a sign of weakness.

His language, in this regard, echoes that used by some of the ancient Sophists. For them, the heroic path, likewise, consists in rejecting “slavish adherence to the group and its doctrines”, and in placing their individual goals and values at the centre of everything, above the needs of others. For example, in Plato’s Gorgias, the Sophist Callicles consistently argues that popular morality is a conspiracy of the weak, who are many, to enslave the strong, who are few, by attempting to make them feel ashamed of using their strength to take more than an equal share. Real men are radical individuals, who rise above popular morality, and become a law unto themselves. Awkwardly, this leads them to conclude that what the Greeks called political “tyrants” (i.e., dictators), who are unafraid to impose their will on others aggressively, provide the best role models for young men.

…he’s essentially replacing the image of Christ on the cross of Calvary with the image of himself as a Sophist, being crucified at the centre of Being.

The Sophists ask “How could a man be happy if he is enslaved to anyone?“ To be a real man, he must be a completely free and unrestrained individual, which is impossible as long as he cares about the feelings of other people.

It is the weaklings, the many, who make the laws... to frighten the stronger men... and to prevent them from getting more than they themselves have.... But if there arises a man sufficiently endowed by nature, he will shake off all these restrictions, shatter them to pieces, and escape. Trampling underfoot our documents, our tricks and charms, and all our laws that violate nature, he rises up and reveals himself our master, who was once our slave. Then the justice of nature shines forth. — Plato’s Gorgias

If I take the interpretation Peterson gives us of his vision of himself on the cross seriously, I would therefore have to say that he, I presume unintentionally, portrays himself as a Sophist Messiah. The message he derives from the dream, and wants to convey to his readers, seems ultimately to derive from the Sophists in Plato’s dialogues. By attributing their critique of “slavish” values, and call to radical individualism, to his mystical vision of suffering and transformation, he’s essentially replacing the image of Christ on the cross of Calvary with the image of himself as a Sophist, being crucified at the centre of Being.

Could Peterson be the Messiah of the alt-right?Conclusion

Could Peterson be the Messiah of the alt-right?ConclusionI don’t think Peterson is the first person to have had a vision where he saw himself swapping places with Jesus Christ. For some mystics, on the one hand, this might be an epiphany. Peterson clearly feels that it revealed his life’s purpose. For most clinical psychologists, on the other hand, it’s bound to sound a bit narcissistic, or even like a typical psychotic delusion of grandeur. For that reason, it is, at the very least, highly surprising that Peterson would open his book in this way without acknowledging the grandiose nature of the claims he is making about himself, and his own importance for mankind, especially as these remarks follow a Foreword, which placed so much importance on comparing him to Moses and his 12 Rules to the Biblical Ten Commandments.

My understanding was that the whole point of the New Testament was that Jesus said he came to “fulfil” the laws of the Old Testament, by restoring their true purpose. He felt that mankind was taking the Ten Commandments and other Jewish doctrines too literally and rigidly, and thereby missing their spiritual meaning. He teaches mankind that the highest commandment, is to love God above all and our neighbours as ourselves, is the spirit of the laws. Peterson sees himself as a Christlike figure but wants us, for some reason, to revert back to the inflexible literalism of the Ten Commandments. Even Nietzsche wanted the Ubermensch to create his own values — he doesn’t present himself as a modern-day Moses, handing down a new version of the Ten Commandments to everyone else.

I think Peterson says some interesting things in the book. I also think he says quite a few very odd things. It’s an unusual book, not least because of the the way it seems to present itself at times not just as a self-help guide but as a sort of manifesto for taking a stand in the Culture Wars. The Sophists combined political rhetoric and self-improvement advice. These two things have always seemed to me to blend together about as well as oil and water. I think Peterson’s portrayal of himself as a Christlike figure and the notion that he’s handing down Commandments like Moses is probably part of what makes him so divisive. That sort of imagery, I would imagine, attracts those who share his values, and are looking for a father figure, but repels those who oppose Peterson’s values, or who value autonomy and the freedom to think for themselves rather than passively acquiesce to an intellectual authority figure.

I suppose only time will tell whether Peterson’s dream, from the Overture to his rule book, will come true or not. By portraying himself as a Messiah figure, however, and then adopting the philosophical stylings of an ancient Sophist his work was bound to become a divisive text in the Culture Wars by reviving the perennial contest between philosophy and Sophistry.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 11, 2025

To will the end you have to will the means...

In the same way, when some people have seen a philosopher and have heard someone speaking like Euphrates (though, indeed, who can speak like him?), they wish to be philosophers themselves.

Euphrates was a Stoic renowned for his eloquence, perhaps a student along with Epictetus of Musonius Rufus. (He’s also mentioned in passing, with admiration, by Marcus Aurelius.)

Man, consider first the nature of the business, and then learn your own natural ability, if you are able to bear it. Do you wish to be a contender in the pentathlon, or a wrestler? Look to your arms, your thighs, see what your loins are like. For one man has a natural talent for one thing, another for another. Do you suppose that you can eat in the same fashion, drink in the same fashion, give way to impulse and to irritation, just as you do now? You must keep vigils, work hard, abandon your own people, be despised by a paltry slave, be laughed to scorn by those who meet you, in everything get the worst of it, in honour, in office, in court, in every paltry affair.

Our duties can be derived largely from our social roles...

In the same way, when some people have seen a philosopher and have heard someone speaking like Euphrates (though, indeed, who can speak like him?), they wish to be philosophers themselves.

Euphrates was a Stoic renowned for his eloquence, perhaps a student along with Epictetus of Musonius Rufus. (He’s also mentioned in passing, with admiration, by Marcus Aurelius.)

Man, consider first the nature of the business, and then learn your own natural ability, if you are able to bear it. Do you wish to be a contender in the pentathlon, or a wrestler? Look to your arms, your thighs, see what your loins are like. For one man has a natural talent for one thing, another for another. Do you suppose that you can eat in the same fashion, drink in the same fashion, give way to impulse and to irritation, just as you do now? You must keep vigils, work hard, abandon your own people, be despised by a paltry slave, be laughed to scorn by those who meet you, in everything get the worst of it, in honour, in office, in court, in every paltry affair.

September 9, 2025

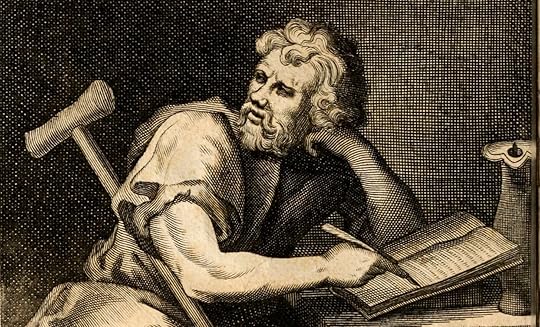

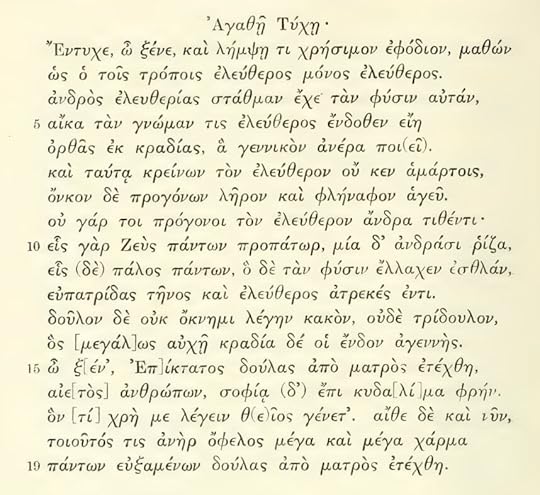

An Ancient Poem About Epictetus

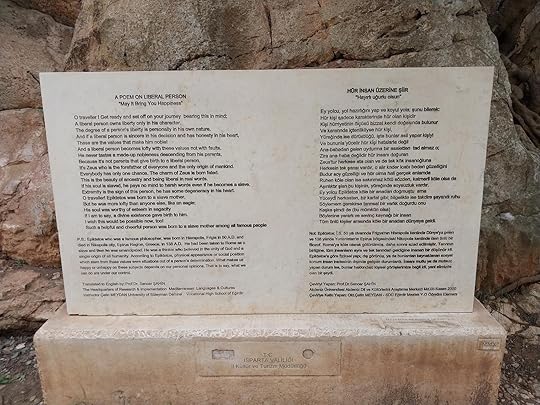

Several years ago I was told about the existence of an obscure inscription that contains a poem praising the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. It may even have been written by one of Epictetus’ students. I have to thank Güney Celbiş for first bringing it to my attention, providing me with his own translation, a photo of the plaque, and the link to the video below. (I found a clearer photo on the Internet, which is the one I’ve used here.) This article contains a new English translation of the poem.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The poem was discovered carved in rock in Yazılı Canyon Nature Park in Isparta, a province in southwestern Turkey. In fact, the place is known as Yazılı Kanyon, literally "Inscribed Canyon," for this very reason. Epictetus was born into slavery in Hierapolis, Phrygia (modern-day Pamukkale in Turkey), and later lived and taught in Rome until he was set free and subsequently went into exile in Nicopolis, Greece, where he established a school. Epictetus was, therefore, originally from what is now the neighbouring province of Denizli, less than a hundred miles from the location of this poem. It notes that Epictetus’ mother was a slave. She probably lived in this region.

The poem seems to commemorate the startling contrast between Epictetus’ humble origins nearby and his subsequent fame as a teacher of philosophy, after being taken to Rome — the story of a local boy made good. The inscription must have been commissioned as an act of philanthropy, and public education, by a wealthy follower of Epictetus, who perhaps lived in the region. The other inscriptions on the rock face state that the author’s name was Leontianos, and that he left his walking stick here as a dedication to the Apollo, suggesting that there was once a shrine to the god here.

O stranger, Epictetus was born from a slave mother,

yet he was an eagle among men, his mind glorious in wisdom.

It happens to lie on the “Kings Road”, a path believed to have been travelled by St. Paul during his first missionary journey, around 47-48 CE, as he brought the teachings of Christianity to the Roman province of Galatia in Asia Minor. Paul would have passed through this canyon to reach his destination, although this was a few years before Epictetus was even born, so long before the inscription existed.

Epigraphers date the inscription to the Roman Imperial period, most likely between 150 and 230 CE. That timeframe is significant because it means that it could potentially have been written by one of Epictetus’ younger students, or at least someone who had met one of his students. Epictetus was at the height of his fame around this time, and his Discourses were in circulation. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius, of course, was a follower of Epictetus’ teachings — though they never met in person. The dating, if accurate, makes it possible that this inscription could have been created during Marcus’ lifetime, and possibly under his rule (161 — 180 CE).

The official plaque that marks the location of the inscription on the canyon’s rock face was placed there by Isparta Governorship's Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. It is written in both Turkish and English and includes a translation of the poem from Hellenistic Greek. It appears to be dated from the year 2000.

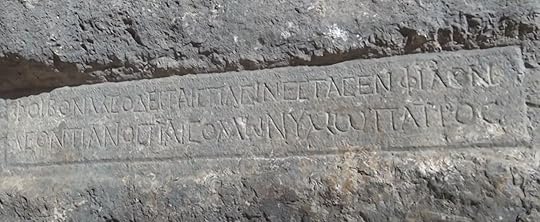

The original inscription, unfortunately, is badly damaged today. Treasure hunters chiseled away the rock face, believing something could be hidden behind it. The modern translation therefore had to be reconstructed from the surviving fragments. The plaque attributes this translation to the renowned Turkish epigrapher Prof. Sencer Şahin. However, I believe the inscription was originally transcribed by the American epigrapher J. R. Sitlington Sterrett, in the late 19th century. He records of his journey to the canyon:

We leave our horses and proceed on foot, the gorge growing narrower and more precipitous all the while. In half an hour we reach the narrowest part at Yaziilii [Kaya]. Here the river has cut its way through the solid rock, and is fully thirty feet deep; it is perfectly clear and swarms with large fish, some lying lazily on the bottom, others swimming around at various depths. The gorge at this point has been widened by artificial means, so as to make a road-bed. The three following inscriptions on the face of the rock show that a sanctuary of Apollo once existed in this wild spot. — Sterrett, J. R. Sitlington. "The Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor." In Papers of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 3 (1884-1885), 315-317, nos. 438-440. Boston: Damrell and Upham, 1888.

The English translation on the plaque is not very literal so I have used Gemini Pro AI to compare information on the Greek fragments to the Turkish and English translations on the plaque, and the translation and comments of Güney Celbiş, in order to create a more polished English version. For reference, I have included the original English translation underneath. (It’s possible that Prof. Şahin made his translation from a later reconstruction of the Greek text than the original one published by Sterrett.)

Pay heed, O stranger, and you will receive a useful provision for your journey,

learning that only he who is free in his character is truly free.

As you will see, the poem not only praises Epictetus, but distills elements of his Stoic philosophy. Its central message is that true freedom is a state of mind, which comes from relinquishing our attachment to external goods, such as wealth and reputation.

Photo by guideofadventureOn the Free Person

Photo by guideofadventureOn the Free PersonTo Good Fortune.

Pay heed, O stranger, and take this useful provision for your journey:

know that only he who is free in character is truly free.

Hold a man's own nature as the measure of his freedom;

if a man be free in judgment, from an upright heart within—

this is what makes him noble.

Judge the free man by these things and you will not err;

do not, then, speak the idle nonsense of ancestors.

For ancestors do not make a man free;

Zeus is the one forefather of all, and one is the root of mankind.

And one is the lot of all; he who has been allotted a good nature,

that man is truly well-born and is free.

But I do not hesitate to call a man an evil slave, even a thrice-slave,

who boasts greatly, yet whose heart within is base.

O stranger, Epictetus was born from a slave mother,

yet he was an eagle among men, his mind glorious in wisdom.

I need not say he was born divine. But I wish, even now,

that such a man—a great help and a great joy—

by the prayers of all, were born from a slave mother.

Part of the inscription, based on a close-up from the YouTube video below.

Part of the inscription, based on a close-up from the YouTube video below.The video clip below shows the area of the pass where the plaque and inscription are located. The section showing an inscription on the rock face, and the plaque nearby, begins at around 13:00 (timestamp). This inscription appears to be the dedication to Apollo recorded by Sterrett, which I believe says:

Leontianos, son of a father of the same name, has set me up, Phoebus [Apollo], as a friend to all travellers.

Sterrett also records a longer dedication, which appears to say:

You, Phoebus Apollo, who watches over these paths,

ever delighting the mind of the traveller with libations,

I, Leontianos, a musical spirit, dedicate this walking stick.

And you, O blessed one, receive with joy

this vehicle for my hand, this support for my knees,

this staff for a traveller, with which I completed my journey,

a guiding hand on the path. And now, being free,

O Phoebus, I will rest here from my former labors.

Below is the English translation of the poem shown on the plaque, which I have included for reference, although I believe the translation above to be better, more faithful to the Turkish source, and probably also closer to the original Greek inscription.

The English Text from the Plaque at Yazılı KanyonA POEM ON LIBERAL PERSON

"May it Bring You Happiness"

O traveller! Get ready and set off on your journey, bearing this in mind;

A liberal person owns liberty only in his character.

The degree of a person's liberty is personally in his own nature.

And if a liberal person is sincere in his decision and has honesty in his heart,

Those are the values that make him noble!

And a liberal person becomes lofty with these values not with faults.

He never tastes a made-up nobleness descending from his parents,

Because it's not parents that give birth to a liberal person.

It's Zeus who is the forefather of everyone and the only origin of mankind.

Everybody has only one chance: The charm of Zeus is born fated.

This is the beauty of sincerity and being liberal in real words.

If his soul is slaved, he pays no mind to harsh words even if he becomes a slave. Extremity is the sign of this person, he has some degeneracy in his heart.

O traveller! Epictetus was born to a slave mother,

But he was more lofty than anyone else, like an eagle;

His soul was worthy of esteem in sagacity.

If I am to say, a divine existence gave birth to him,

I wish this would be possible now, too!

Such a helpful and cheerful person was born to a slave mother among all famous people.

Sterret’s original reconstruction of the ancient Greek

Sterret’s original reconstruction of the ancient GreekIf you have any more information about the inscriptions at Yazılı Kanyon, please get in touch or comment below, especially if you live in Turkey, and may have some local insight. Thanks for your support!

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 4, 2025

Substack Live: You are invited to "Stoicism and Anger"!

POSTPONED — Apologies for any inconvenience but today’s Substack Live on Stoicism and anger has been postponed due to technical issues.

How do the Stoics conceptualize anger? Is there such a thing as healthy anger? And what do Marcus Aurelius and Seneca have to say about it? Use your mobile device to join us at 5pm eastern time today for a free discussion on Substack Live. Everyone is welcome!

Hosted by , you will need to use the Substack app on your mobile device to join this live event.

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Donald J. Robertson in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash The Stoa LetterFree Live Event w/ Donald Robertson Thursday Sept 4 | Stoicism and AngerHow do the Stoics conceptualize anger? Is there such a thing as healthy anger? And what do Marcus Aurelius and Seneca have to say about it…Read more5 days ago · 29 likes · 2 comments · Michael

The Stoa LetterFree Live Event w/ Donald Robertson Thursday Sept 4 | Stoicism and AngerHow do the Stoics conceptualize anger? Is there such a thing as healthy anger? And what do Marcus Aurelius and Seneca have to say about it…Read more5 days ago · 29 likes · 2 comments · MichaelThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Back to School: How can Stoicism Help us as Parents?

Photo by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash

Photo by Vitaly Gariev on UnsplashI have one child who is a night owl, and one who is an early, crack-of-dawn riser. Did I choose for one daughter to stay up very late ever since she was a toddler, so late that she feels super tired in the morning even now as a teen? And did I decide that my other daughter would be the opposite, always waking up with the sun and getting fatigued in mid-evening?

No, of course not!

But many modern moms and dads have a preconceived notion that they should be able to “control” their kids and shape them into perfect beings through their parenting. It makes being a mom or dad these days even harder than it needs to be.

Luckily, I have some words of wisdom for this predicament: applying Stoic thinking to your parenting can help. That’s even more important now, during this sometimes-tense transition time of back-to-school season here in the US.

How can Stoicism Help?

How can Stoicism Help?One of the core principles of Stoic parenting is the recognition that our kids’ behaviors are up to them, not to us. We can guide our kids and create meaningful consequences for their actions, but in reality, children are not strictly under our control. I didn’t decide to have kids with vastly different internal clocks, for example, and I also did not choose any of my kids’ physical traits and their basic personalities and temperaments.

Just acknowledging that makes parenting less inherently stressful on us as parents, while it also helps us gain a healthy perspective on your role. Stoicism can help us become more aware and more accepting of what being a mom, dad, or caregiver is really like.

Plus, there’s a silver lining. It comes when we realize that the goal is not to control our kids, but to build their character and help them grow into responsible, independent individuals who can use their own judgment and pursue the Stoic virtues of wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. This is the rational side of Stoic practice. What’s more, we can also guide them toward becoming people who care about their communities and their fellow humans in general, embedding the prosocial side of Stoicism in our children, the side that is rooted in Stoic cosmopolitanism.

Remember that if you choose to adopt Stoicism as a parent, you’re swimming upstream in a society obsessed with looks, money, status, and outward achievements. And you’ll feel it when other people ask questions or look at you funny. What’s more, kids are under huge pressure to perform in school, sports, competitive activities, and even on social media. It’s a tough job, but in essence, it's our role to inculcate how to live well beyond superficial external things and to make clear to our kids that their value is not in their wins or grades or social media likes, but instead in their choices that move them closer to virtue.

The Stoic MomHow parents, caregivers, and kids can benefit from Stoic life philosophyBy Meredith Alexander KunzTop Tips from Stoicism

The Stoic MomHow parents, caregivers, and kids can benefit from Stoic life philosophyBy Meredith Alexander KunzTop Tips from StoicismTo move in that direction, here are my top pieces of advice for Stoic-inspired parenting.

Start with the fundamentals: helping your kids become independent and make good choices

Question your knee-jerk emotions and reactions to situations with your kids and teach them to do the same

Use your spark of reason to be a more calm, kind, and rational parent, and share how thought process with your kids

Remember the importance of oikeiosis, or personal growth, both for you and your children

All of these approaches apply to both parents/caregivers, and to kids. Below, I’ll share more details on each one.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Get the Fundamentals RightIt begins with fundamentals. As Musonius Rufus once said about educating children:

We must start by teaching children that this thing is good that thing is bad, that this thing is helpful and that thing is harmful, and that this thing must be done and that thing must not be done. (Lecture 4.7)

We can teach our kids to share, to show respect and kindness, to learn and to teach, and to help others. We can teach them not to cheat, not to be mean, not to be entitled or selfish. It’s not going to happen by lecturing our kids, but instead, by doing. We can show them good actions through our own actions, and thoughts by expressing our own thoughts, and decisions by sharing our own decision-making process. From early elementary school onwards, they can learn from watching us and listening to us, and from coming to understand what we place value on. In addition, we can allow them to experience natural consequences of their actions, rather than stepping in and “protecting” them from repercussions.

Take a very simple example: If your kid forgets her homework at home, rather than driving it to school for her when you see it on the kitchen table, leave it there. Let her feel what it’s like not to have her homework. It’s a valuable lesson that might offer future reminders. Maybe she’ll even learn to make her case to her teacher to allow for one late homework. I recall one very painful weekend when my daughter realized she’d never turned in a bunch of homework to her foreign language teacher, and her final grade for the semester would likely go down by a lot as a result. Stress and tears ensued. Eventually, she was able to negotiate with her teacher to hand in some work late for half points, and lifted her score just enough to be happy with it.

Question Knee-Jerk ReactionsAs anyone who has done babysitting let alone parenting knows, young kids are driven by lots of instinctual emotions and reactions. They melt down if they can’t get what they want, and often they don’t understand the importance of sharing or helping. It’s our role as parents to help them grow and move past this phase. It’s easier said than done, but by recognizing the process we’re in with our kids, we can give ourselves the strength to help them find a better way.

In the movie Frozen 2, there’s a song that stood out to me for its Stoic messages: “Do the Next Right Thing.” Anna, who sings the song, feels abandoned. She is trying to figure out the way forward (literally, hiking out of cave-like hole) and she’s scared. Her knee-jerk reaction is fear. But she decides that going one step at a time, making each next step count, will bring her to a good outcome and eventually help her find her sister again.

We can “do the next right thing” as we move through life, including in our parenting. Stoic thinking focuses on what you can in the current moment. It’s about letting go of the emotional baggage of what’s come before and doing the next right thing.

As a mother, I guide my kids to learn for themselves how to choose the next right thing, and how to avoid making knee-jerk reactions but to judge their emotions and thoughts with accuracy. To set aside distracting fears and anger and sadness, and to keep acting in the present. We have a lot of conversations about how to make decisions.

For example, kids are confronted with a ton of decisions at school. Who to sit with or play with at lunch or recess; what to do if someone tries to bully or tease you; when to raise your hand and try to answer a hard question; what to focus on in projects or papers; which clubs or sports to join; and much more. Training the decision-making part of the brain will help will help them immensely.

It’s easy to fall into cognitive distortions like catastrophizing about how a situation could be disastrous. This can paralyze our decision-making. If this had happened to Anna, she might still be stuck in that hole. So remembering to “not believe everything you think” and feel, and taking a closer look at the actions available to you, is critical!

Our Spark of ReasonBut how can we, and our kids, figure out the next right thing? In moments of uncertainty, I try to recall that I have a spark of reason deep inside, according to the Stoics. If I pause, I can attempt to figure out the next right thing. As I face what’s in front of me, I can ask “is this really true? Is this wise? Is it brave? Is it just and fair?” and turn the answers into motivators for better decisions as a mom (and as a person).

This counterbalances the irrational side of things, which often springs from fears about things spiraling out of our control, or forms of anger or insecurity—"bad passions” in a Stoic sense. It is completely understandable to feel frustrated with our kids. But if we make efforts to really understand who they are as people and acknowledge their character, we can work with them on their level—so they can begin to understand what’s up to them.

When they are old enough to realize that they are making choices and that their actions impact others, we can begin to teach them how to behave in a way that strives for the Stoic virtues of wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. Stoicism can help us maximize our agency (according to modern Stoic thinker Lawrence Becker), and to use it to make rational and pro-social choices.

A quick example for us as parents. You’re at a restaurant, waiting for food, and your elementary-school child starts whining to use your phone as entertainment. You have already set a rule that you have no phone “fun time” at the dinner table, at home or away. Do you give your child the phone to help them pass the time quietly, or do you withhold it and face more whining and possibly crying, but also potentially more interaction and conversation with your kid?

Having been there myself, I’ve tried both. But if I gave them my device when they were young, I didn’t feel very good about it. I knew I wasn’t developing my courage, or their temperance, in that moment. It didn’t seem wise either since I knew it would just encourage more whining, and less social interaction. Noticing all of that helped guide my behavior and response to my kids—who now, as older teens, are quite annoyed when other folks they’re eating with would rather look at their phones than talk to them!

Not Taking it PersonallyIt’s important to try, when dealing with kids, not to take things personally—and to use reason to avoid that. I’ve noticed it happening when we think our child’s actions are a reflection on us as people; and also, when we feel we’re disrespected or disliked by our kids. I’ve worked to become self-aware about it. This is another way of taking back our power to decide how we want to feel and act.

A long time ago, I remember being very embarrassed when my toddler had a meltdown in a public place. Looking back, it was pretty obvious what was going on. My kid was absorbed by her own emotions, her proto-passions in a Stoic sense. She was too young to understand her own feelings or get a handle on them. I did the best I could: Taking my daughter out of the situation where the tantrum took place, explaining to her why this behavior isn’t the way we get what we want, and giving her time and tools to calm down. The tantrum wasn’t a reflection on my parenting. My child was young and on her own journey to learn how to manage negative emotions.

There's another reason why we should ask ourselves if we are taking something that our kids do too personally. Some moms and dads grew up in homes where it wasn’t permitted to go against their own parents, and where they were supposed to be “seen and not heard” as kids. It's possible that, if you are used to that mindset, any kind of disobedience from children could be disturbing. We can use our reason, however, to discern if a kid’s behavior is truly a worrying act of defiance that could cause serious consequences, a pattern of behavior that shows bad intentions and unethical tendencies—or just a small, fleeting issue.

An example: What if your kid is rude to you? I have been there, and it’s not a good feeling. Expressing your own anger will probably backfire, as Seneca would explain (anger is temporary madness in his description). We can, instead, model better behavior if we can say something calmly and firmly about everyone deserving respect and common courtesy. Consequences such as privileges being withheld temporarily until the child’s behavior reflects this sense of respect for others could also be appropriate. After all, we are trying to raise rational and pro-social humans!

Even if kids (and parents) make mistakes, we can keep trying, and keep growing. The Stoic ideal of lifelong development (oikeiosis) emphasizes that we can keep moving on the path towards virtue and happiness for ourselves, and our children can do so too.

For example, if my kids are overwhelmed by schoolwork or other challenges and say “I can’t do it,” I’m right there asking, “OK. Let’s think about what you can do? How can you take back your own power over what you can choose to do or to think in this situation?”

And when it comes to seeing our kids making mistakes, we also can take the chance to remind ourselves, “I did the best I could in that situation… I’ll talk to my child about how to handle this better when she calms down/is in a better mood/is more rested, etc.” (Remembering that if what they are doing could be dangerous, we may need to take quick action to stop it.) This is the one most critical thing that’s made me less irritable and anxious as a parent. And it has helped put my children in the driver’s seats of their own futures, as they developed the ability to learn, grow, become more resilient, and make their own choices.

Just one more thought as you travel along the path of parenthood: When being a mom, dad, or caregiver gets hard, here are words from Epictetus to help you persist—

With regard to everything that happens to you, remember to look inside yourself and see what capacity you have to enable you to deal with it… if hard work lies in store for you, you’ll find endurance; if vilification, you’ll find forbearance. (Handbook, 1.10)

Here's wishing you all good things for the new school year!

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Meredith Alexander Kunz is the author of The Stoic Mom Substack, co-author (with Massimo Pigliucci and Gregory Lopez) of Beyond Stoicism: A Guide to the Good Life with Stoics, Skeptics, Epicureans, and Other Ancient Philosophers, and Live Like a Philosopher: What the Ancient Greeks and Romans Can Teach Us About Living a Happy Life, and host of The Philosopher’s Compass Podcast (YouTube, Spotify, Amazon Music)

The Stoic MomHow parents, caregivers, and kids can benefit from Stoic life philosophyBy Meredith Alexander Kunz

The Stoic MomHow parents, caregivers, and kids can benefit from Stoic life philosophyBy Meredith Alexander Kunz