Welcome to the Neurotic Paradox!

Why do people continue to do things that are clearly not in their best interests? It can seem obvious, from the outside, when a friend’s behaviour is self-defeating. And yet they may continue very persistently to sabotage themselves. Ovid, the Roman poet, captured it well, in a famous piece of verse from his Metamorphoses:

Desire is persuading me one way,

reason another. I see the better course and I approve it,

but I follow the worse. — Metamorphoses, 7,19-21

In 1948, O. Hobart Mowrer, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois, who would later become president of the American Psychological Association (APA), published an article titled ‘Learning theory and the neurotic paradox’, which attempted to explain this puzzling, but universally recognized, phenomenon.

Stated in its most general form, the neurotic paradox is this: How is it that behavior which is manifestly unrewarding and even self-defeating can persist over a long period of time, in persons who are not manifestly psychotic or mentally defective? From the standpoint of common sense and from the standpoint of much contemporary learning theory, such behavior is paradoxical in the extreme. — Mowrer, 1948, my italics

In other words, unless perhaps an individual has very severe cognitive impairment, we might expect them to learn from their experience and, eventually, stop doing things that are clearly making their life worse. But often they don’t. So what’s going on?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Mowrer proposed a simple clinical theory, which combined two different forms of behavioural psychology, which was once called “learning theory”. It’s known as the “two-factor theory” of neurosis. Despite its simplicity, Mowrer’s hypothesis has largely stood the test of time. (I’ll discuss some caveats and modifications at the end.)

Modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) combines ideas from cognitive and behavioural psychology, two rival traditions in the social sciences. It also combines both behavioural and cognitive approaches to treatment. Although many clinicians have forgotten about Mowrer’s original “two-factor” theory, it is actually the cornerstone of virtually all of the behavioural psychology models used in modern CBT.

Mowrer was right, basically. Like most theories that hit the nail on the head, his innovation ended up being taken for granted. It’s become the clinical equivalent of “common sense”, so much so that Mowrer is now seldom referenced or given the credit that he is due for his innovation. Yet his basic insight remains foundational. We are still in the grip of the Neurotic Paradox today.

Photo by Hasan Almasi on UnsplashThe Two-Factor Theory

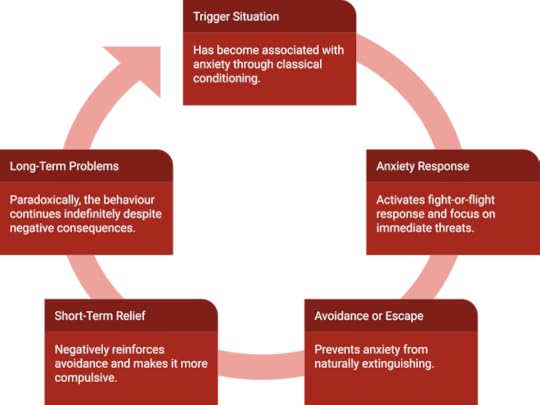

Photo by Hasan Almasi on UnsplashThe Two-Factor TheoryThis is how Mowrer explained the Neurotic Paradox, which had puzzled people since before even the time when Ovid was writing. It uses two well-established forms of conditioning or “learning” theory.

First Factor: Pavlovian (Classical) ConditioningIn plain English: We learn to feel irrational anxiety in response to things that were repeatedly associated, over time, with triggers that naturally cause anxiety. For instance, if every time a child tries to speak, they’re yelled at to keep quiet, they may eventually learn to associate feelings of anxiety with any efforts to speak in public. (In technical terms: through the repeated association of a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus, which triggers an unconditioned response, a conditioned stimulus-response reaction is established.)

This explains why we feel irrational anxiety. Over time, we build up an association between anxiety and certain triggers, or situations, which may no longer actually present any threat to us. It has become a habit to feel anxious, even though we’re no longer in danger. Pavlov trained his dogs to salivate whenever they heard a bell ring, by pairing the bell repeatedly with the presentation of food. Instead of salivating, their early childhood experiences can train humans to feel anxiety (or other feelings) involuntarily in response to certain cues or signals.

Let me also apply this to relationships. Someone who repeatedly watched their parents fight, as a child, may have been conditioned to feel intense anxiety whenever they perceive signs of conflict in a relationship. Later, in adult life, when a potential conflict arises in their own relationship, even if it’s mild and could be easily resolved, they have learned to respond with intense anxiety. This may appear “irrational” or out of proportion to the real situation because it’s not a “natural” response to a “real” threat. Rather, it’s a conditioned response to a conditioned stimulus that has been built up through habit and association, perhaps even without us being fully conscious of how it was learned.

The first factor explains why our anxiety can seem “neurotic” or “irrational” but it doesn’t explain why our behaviour would seem neurotic. In fact, conditioned anxiety would normally be expected to wear off over time, through a process technically referred to as “extinction” or “emotional habituation”. If, as kids, I punched you really hard on the shoulder every time I said the word “Surprise!”, after a while the word alone may have made you jump involuntarily. But eventually this anxiety reaction would wear off. You wouldn’t still expect to be jumping out of your skin every time you hear the word “Surprise!” twenty or thirty years later. That’s not how classical conditioning normally works — it usually wears off naturally unless something maintains it. So why does neurotic anxiety and behaviour, set up in our youth, persist so long into adult life, and perhaps even permanently?

Second Factor: Operant Conditioning

Second Factor: Operant ConditioningThe other major approach to learning theory is known as “operant conditioning”. To most people this is familiar as the process of “reward and punishment” that forms the basis, for instance, of training animals. Pavlov noticed that a dog can be conditioned to involuntarily salivate every time it hears a bell, if that has been repeatedly associated with the presentation of food (when the dog was hungry). Later psychologists observed that a dog, for instance, could be conditioned to raise its paw voluntarily every time a signal is given, if it is repeatedly rewarded for making approximations to performing this behaviour. Maybe it lifts its paw a little, and is rewarded with a treat, then a little more next time, and given a treat, and so on, until the desired behaviour has, step by step, been “shaped” through what is known as “positive reinforcement”.

We call it “positive” reinforcement when something happens that the dog likes, such as receiving a treat or a pat on the head. (That’s a simplification, reinforcement is technically anything that increases the probability of the behaviour, but for our purposes we can think of it as receiving a treat.) So far so good but there’s another form of reinforcement, which is often slightly more subtle and indirect, and shapes neurotic behaviour even more powerfully. It’s called “negative” reinforcement, not because it’s “bad” or “unpleasant”, but because it consists in removing or avoiding something we don’t like. (Negative reinforcement is therefore not to be confused with punishment, a very different concept.) You can think of it, crudely, as not a direct reward or treat but rather the sort of thing that brings about a feeling of relief. “Thank God that’s over!” Neuroses, or emotional problems, are built primarily on a foundation of negative reinforcement.

The icing on the cake of Mowrer’s theory was that once we have acquired neurotic anxiety through classical conditioning, we also end up behaving in neurotic ways that temporarily avoid or alleviate it. Suppose I have a fear of public speaking. I may feel an overwhelming urge to “avoid” ever getting into any situations where I’m expected to speak in public. If I do find myself, unexpectedly, the centre of attention, and expected to speak in public, I may do whatever I can to “escape” the situation as rapidly as possible — perhaps by making my excuses and dashing for the door. Of course, that’s not going to help me much in the long-run. It may lead to a variety of personal and interpersonal problems. So why do we do it?

Avoidance relieves anxiety in the short-term but maintains it in the long-term.

The biggest problem is that it will prevent the anxiety from ever extinguishing, or wearing off naturally. Avoidance relieves anxiety in the short-term but maintains it in the long-term. Avoidance is the world’s number one most popular coping strategy but it’s like constantly picking at a scab — every time you avoid an irrational fear, you keep the wound from healing. Worse, through constant negative reinforcement, our behaviour will not only become more likely but eventually it will become faster, less conscious, and more automatic. We’ll start to feel ourselves avoiding trigger situations more compulsively, and in more subtle ways. It will become increasingly hard for us to resist engaging in this behaviour because it has been powerfully reinforced countless times, over many years.

The core of the neurotic paradox is the simple fact that anxiety compels us to engage in avoidance behaviour, which maintains our irrational feelings. It’s a vicious cycle. The anxiety should normally wear off over time, without reinforcement. (Nothing catastrophic happens that would make us feel realistic anxiety.) The unhelpful behavior should normally fade away too, without reinforcement. (Nothing positive happens as a result of our avoidance.) However, the opposite happens, and we’re caught in a trap, going round in circles. The anxiety compels us to act in a way that maintains it, and the behaviour is negatively reinforced, because it relieves the anxiety.

If I avoid public speaking situations, I’ll never get over my anxiety. Moreover, my urge to avoid them will bring temporary relief, which will eventually make make me, in layman’s terms, “addicted” to avoidance. Avoidance feels good, or at least it feels better than anxiety. Over the years, this will make our neurotic behaviour more and more compulsive, until we’ll find ourselves struggling to overcome it, even though, like Ovid, we may realize it’s doing us more harm than good in the long run. The long-term consequences of our actions are not usually powerful reinforcement. The relief from anxiety that avoidance brings is virtually immediate, and extremely powerful, so that it overrides our concern about the longer-term consequences of our behaviour.

Okay, so it’s a simple theory, but there are a couple of moving parts here, so let’s apply it again to our previous example. Someone who repeatedly watched their parents fight, as a child, let’s suppose has learned to associate anxiety with perceived signs of conflict. It’s an over-generalization that no longer helps them, and it should just wear off normally, but it won’t if they engage in avoidance, and avoidance can take many subtle forms. Suppose they discovered, as a child, that “keeping the peace” and “people pleasing” can help them to avoid the threat of conflict, and thereby relieve their own anxiety. Those behaviours will probably, over the years, become deeply-ingrained and compulsive.

As an outside observer, it may be glaringly obvious that, for instance, this individual is remaining too long in an unrewarding job or an unhealthy, or even abusive, relationship. Why can’t they see that? Because their submissive people-pleasing coping strategy has been powerfully negatively reinforced, so many times, that it’s become compulsive and maybe even part of their personality. The long-term benefits of leaving and finding a new job or relationship seem vague to them, whereas the anxiety-relief that comes from behaving submissively is instantaneous and overwhelming. They sacrifice their long-term happiness, for short-term relief from anxiety, because that’s how conditioning works.

Even worse, the more anxiety they feel, the harder it will be for them to focus on the long-term benefits of behaving in an autonomous and assertive manner. When we are anxious, our brain goes into an emergency mode, in which it largely shuts down reasoning in terms of the longer-term, and focuses on survival in the present moment. So we reach for avoidance as the best solution, although our lack of assertiveness traps us even deeper in the situation that’s causing us problems.

Orval Hobart Mowrer (1907 — 1982)The Solution

Orval Hobart Mowrer (1907 — 1982)The SolutionIf the Neurotic Paradox sounds pretty bleak, the good news is that Mowrer’s theory offers us a road to salvation because it points to a very clear solution. The beauty of this theory is that it applies to countless different forms of avoidance, and different forms of maladaptive behaviour. Sometimes that can make it hard to fully comprehend the implications, because they’re so pervasive across different situations. So I’ll give two different examples for comparison.

Suppose you are afraid of public speaking, as we described above. The solution would be to abandon the avoidance behaviour and, instead, to face your fears consistently. That’s not easy to do but it’s the foundation of what we now call Exposure Therapy, perhaps the most robustly-established treatment in the entire field of research on psychotherapy. By facing our fears patiently, and enduring the anxiety, it will eventually extinguish, as long as we completely abandon the avoidance behaviour. Although that is difficult at first, if we can resist the urge to run out of the door, because the anxiety abates, the compulsion to avoid the situation will also eventually cease too, as it’s no longer being maintained by anxiety relief or “negative reinforcement”.

Now let’s turn to our slightly more subtle example. Suppose someone has learned to feel anxious about interpersonal conflict, and so they avoid it in more subtle ways, such as “people pleasing” and neurotic agreeableness. If they can learn to accept the anxious feelings rather than trying to avoid or control them, and engage in assertive behaviour regardless, over time, their anxiety will naturally abate. They will learn that nothing catastrophic happens and that even if their partner is upset, they can cope with it, if they approach it in the right way. As the anxiety reduces, the negative reinforcement that maintains the compulsive people-pleasing will be extinguished. When this happens, although it may seem very simplistic to phrase it this way, people will often say things like “I just realized, it wasn’t worth it anymore”, as their underlying incentive to engage in dysfunctional behaviour has gone.

ConclusionMowrer’s two-factor theory was, in my opinion, a stroke of clinical genius. It is, however, nearly eighty years old. It’s remarkable that it still retains so much explanatory power, and plays a role in even very recent cognitive-behavioural conceptualization models. Avoidance can take many forms, from obvious behavioural avoidance (e.g., “running out of the room”) to subtle avoidance such as avoiding eye-contact, avoiding talking about certain subjects, distracting yourself, “positive thinking”, superstitions, and any number of other safety-seeking strategies.

Although it’s usually applied to anxiety disorders, the Two-Factor theory also applies to other emotional problems, including anger and depression. Behavioural psychologists have understood depression largely as a deficit of positive reinforcement but we now know that it is also maintained by avoidance and therefore negative reinforcement, not unlike anxiety. For example, a depressed person may try to avoid unpleasant feelings such as boredom and sadness by distracting themselves from them, using drugs, having sex, watching television, playing games, and so on. This behaviour can start to become compulsive, in just the way that Mowrer described. Anger itself can be seen as a “secondary emotion”, which arises as an attempt to cope with anxiety, or emotional pain, and thereby itself becomes negatively reinforced, more or less as the Two-Factor theory describes.

We now realize that many other factors can maintain problems such as public speaking anxiety or people-pleasing behaviour, and so on. For instance, many forms of anxiety, such as fear of snakes and spiders, appear to be innate and are probably due more to lack of exposure than classical conditioning — but this is probably a minor distinction. Most notably, our cognitions — our thoughts and beliefs — have a powerful influence on our feelings and actions in anxious situations. Nevertheless, there’s an interplay between the behavioural conditioning processes described by Mowrer and the cognitive processes that are emphasized in modern cognitive therapy, such that most clinicians tend to work on both levels at once, or at least to alternate between them.

The benefit of Mowrer’s theory is that it really highlights the self-defeating (paradoxical) nature of our behaviour, and drawing attention to this is the first step toward changing it. The Two-Factor Theory makes it clear that the solution consists primarily in reversing our avoidance behaviour, and facing our fears, consistently enough for the anxiety to be allowed to wear off naturally. But it also helps to explain why people are so reluctant to do this in the first place: because anxiety is unpleasant and our avoidance has become such a strong habit that it’s somewhat compulsive. So drop your avoidance, and safety-seeking, face your fears, persist, go through the fire of anxiety, and you’ll emerge from the other side eventually, at the promised land of better long-term consequences for your own mental and physical health, and your relationships.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.