Donald J. Robertson's Blog

October 16, 2025

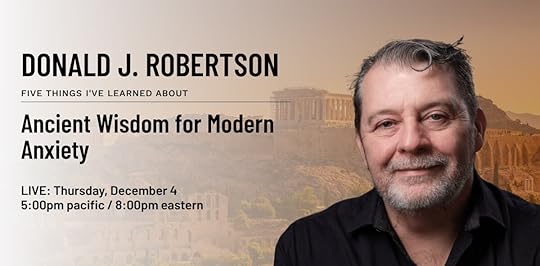

Five timeless lessons that changed how I deal with anxiety

Hi everyone,

Last week, I announced my upcoming live workshop with Five Things I’ve Learned, and I’ve been thinking more about what I most want you to take away from it.

Over the years of studying both psychotherapy and Stoic philosophy, I’ve returned again and again to five simple ideas that help people (myself included) find calm when life feels overwhelming:

The View from Above — how changing your perspective can shrink even the biggest worries.

Premeditation of Adversity — the Stoic art of preparing for adversity before it happens.

Stoic Mindfulness — learning to observe your thoughts instead of being ruled by them.

Virtue & Character — finding strength and confidence in your own strengths and values.

Contemplating the Sage — drawing on timeless role models like Socrates or Marcus Aurelius.

My colleagues and I are turning these five insights into a visual Stoic Resilience Infographic — a kind of quick-reference “cheat sheet” for resilience — which I’ll be sharing with everyone who attends the workshop.

If you’d like to go deeper into the ideas behind it, I’d love you to join me live on Thursday, December 4 at 8 pm Eastern. It’s a two-hour practical session on how ancient wisdom can help us face modern anxiety.

Several readers have said this topic feels especially timely.

If you register now, you’ll be among those to receive the Stoic Resilience Infographic when it’s released.

“Donald’s ability to make ancient philosophy practical and relevant to daily life has been a game-changer.” — Jane S., course participant

See you in December,

PS. Check out on Substack for more details.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 15, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: Values Chameleons

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. Scott and Kasey discuss the trouble with mistaking preferences for values. Also, why we can’t use sacrificing our values as a bargaining chip, call it a forced wager, and blame the house for our “lost investment” when the relationship goes bust.

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 14, 2025

Video: Modern Stoicism for Modern Life

The Centre for Inquiry Canada (CFIC) is a non-profit educational organization dedicated to the promotion of scientific skepticism, secularism, and rational inquiry. Check out my recent interview with them, discussing Stoicism, Socrates, and self-improvement.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 9, 2025

What to Expect When You're Dead

In this episode, my guest is Robert Garland, a British classical philologist and historian who is the Roy D. and Margaret B. Wooster Professor of the Classics at Colgate University. He is the author of numerous works on ancient Greek and Roman history, including The Greek Way of Death and Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks. His most recent book, however, is What to Expect When You're Dead: An Ancient Tour of Death and the Afterlife.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsIn your research, what most surprised you about how ancient cultures looked at death?

What do we gain by thinking about death? For example, a central Stoic practice is called memento mori—reflecting on one’s mortality. They think wrapping our heads around death can help us to live more wisely, do you agree?

Your book examines beliefs from Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and Mesopotamians. Are there any common factors? What are the biggest differences between them?

Did groups within these cultures who faced death more frequently, such as soldiers or perhaps Roman gladiators, have a different perspective on death?

How did ordinary Greeks and Romans differ in their beliefs from the sort of thing we find in the writings of ancient philosophers? To what extent did philosophical views influence popular culture?

Many people today turn to philosophy, and Stoicism in particular, to regain a sense of control in uncertain times. In a world where so much was attributed to fate or the gods, how did the contemplation of their own mortality console people facing hardship and loss?

Has your own attitude toward death changed as a result of your research?

LinksThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 8, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: The Philosophy of Love and Relationships

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. Scott and Kasey discuss the forthcoming virtual event for Plato’s Academy Centre and its featured speakers. They also talk values chameleons: taking on the shade of your partner to ensure the survival of the relationship.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

🔥 Bestseller Deal: How to Think Like Socrates — 65% Off Today!

Snap up a bargain! My latest book, How to Think Like Socrates, is currently 65% off on Amazon com, as part of their Prime Big Deal. Today only!

Outside the US, you may find similar offers available in other regions. For example, there’s currently 18% off in the UK. Outside of Amazon, you may sometimes find other retailers have their own deals competing with Amazon’s.

As with How to Think Like a Roman Emperor I end the book in tears. A beautiful telling of the life and times of Socrates. Robertson’s interpretation of Socrates’ interactions with friends and colleagues adds a richness and depth… The sequel to How to Think Like a Roman Emperor we didn’t know we needed. — Amy, Audible Reviewer

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 7, 2025

Ancient Wisdom for Modern Anxiety — Join My New Live Workshop

Hello everyone,

I’m excited to share something new. This December I’ll be teaching a live, two-hour online workshop as part of the Five Things I’ve Learned series:

👉 REGISTER NOW: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Anxiety

📅 Thursday, December 4 — 8pm Eastern

For over two decades I’ve studied the Stoics — and used their wisdom alongside modern cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Again and again, I’ve seen how their timeless techniques can help us manage stress, quiet anxious thoughts, and build resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

In this workshop, I’ll share five of the most powerful Stoic practices you can start using right away, including:

How to shrink worries with the “View from Above”

How to prepare for adversity with Premeditatio Malorum

How to step back from anxious thoughts using Stoic-inspired CBT methods

How to anchor yourself in your values and character

How to create your own inner mentor to guide wiser decisions

This isn’t a lecture on philosophy. It’s a practical guide to tools you can actually use.

What others say about my teaching

“What sets Donald’s teaching apart is how he ties ancient philosophy to Stoicism and modern cognitive therapy, making it highly relevant and useful for living in today’s world.” — Wayne Mahoney

“I was seeking ways to become more emotionally resilient, and Donald’s course helped me to do that.” — Melanie Wight

“Got into Stoicism recently and it really does change how your mind works dramatically. For someone with ‘issues’ this is priceless.” — Jamie Busby

Reserve your spot now

Tickets are $60, and space is limited for the live Q&A.

👉 Reserve Your Seat Here

Coming soon…

In the lead-up to the workshop, I’ll be sharing details of some new resources — an infographic guide to five Stoic secrets for resilience and a worksheet for decatastrophizing. Sign up now and you’ll receive these as bonus content at the event.

I’d love for you to join me live. This will be an opportunity to explore ancient wisdom in a very practical way — and to apply it directly to one of the biggest challenges of modern life: anxiety.

See you in December,

PS. Check out on Substack for more details.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 2, 2025

Our duties can be derived largely from our social roles...

Our duties are in general measured by our social relationships. He is a father. One is called upon to take care of him, to give way to him in all things, to submit when he reviles or strikes you. “But he is a bad father.” Did nature, then, bring you into relationship with a good father? No, but simply with a father. “My brother does me wrong.” Very well, then, maintain the relation that you have toward him; and do not consider what he is doing, but what you will have to do, if your moral purpose is to be in harmony with nature. For no one will harm you without your consent; you will have been harmed only when you think you are harmed. In this way, therefore, you will discover what duty to expect of your neighbour, your citizen, your commanding officer, if you acquire the habit of looking at your social relations with them.

September 30, 2025

Anger: The Alternative Aristotle

Everyone agrees that excessive anger can do harm. However, at least in the west, the majority of people today assume that mild or moderate anger can potentially be helpful. Especially if it’s channelled toward what they consider to be constructive ends, such as protesting against perceived injustice. In academic literature, the view that a certain amount of anger can be justified is often traced back to Aristotle, who, it is generally believed, taught that anger can be healthy in moderation, in accord with his famous ethical doctrine of the Golden Mean. In contrast to this view, the Stoics, in the west, and the Buddhists, in the east, traditionally adopt a harder line that rejects all anger as unhealthy.

Indeed, in On Anger, Seneca repeatedly opposes the Stoic theory of anger to what he considers to be the standard Aristotelian position. He argues that whereas Aristotelians believe that anger can sometimes be appropriate, the Stoics reject all anger as intrinsically unhealthy.

Aristotle says: “Anger is necessary, nor can any struggle be carried to victory without it: it must fill the mind and kindle the spirit, but it must be employed as a foot soldier, not the general.” — Seneca, On Anger, 1.9.2

Aristotle does not actually say this, however, or anything like it, in any of his surviving works. One possible interpretation of this is that Seneca may be quoting later authors in the Peripatetic tradition and retroactively attributing their view to Aristotle, the founder of their school. Nevertheless, Seneca insists that what he considers to be the conventional Aristotelian view stands in stark contrast to that of the Stoics.

Aristotle stands as a defender of anger and forbids us to excise it: he says it’s a spur to virtue, and removing it will leave the mind defenseless and too sluggish and supine to undertake great actions. — Seneca, On Anger, 3.6.3

The doctrine being attributed to Aristotle by Seneca came to be known as metriopatheia (the moderation of certain passions) as opposed to Stoic apatheia (the elimination of certain passions), where anger would be a key example of the sort of passion concerned. As we shall see, Aristotle’s surviving remarks on anger are fragmentary, appear inconsistent, and therefore lend themselves to different interpretations.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What Aristotle Seems to BelieveThe key passage in which Aristotle describes the relationship of the wise and virtuous person to anger reads as follows:

Concerning anger [περὶ ὀργῆς], the mean is gentleness [πραότης]. [...] The excess is irascibility [or quickness to anger, ὀργιλότης], the deficiency an incapacity for anger [ἀοργησία]. — Ethica Nicomachea, 1125b26–29

First, we should note that Aristotle is not simply referring here to “anger” as an emotional state, which modern psychologists call “state anger”, but rather to our disposition or proneness to anger, which modern psychologists call “trait anger” — he’s talking, in other words, about our character. Second, we should note that ancient thinkers (with the exception perhaps of Plato) viewed our emotions, or “passions”, such as anger, not as feelings occuring in a distinct part or region of the mind but as psychophysiological states encompassing the whole psyche.

Aristotle here defines the virtuous ideal, or “mean”, as lying somewhere between excessive “irascibility”, by which he means proneness to anger, and its opposite, “inirascibility”, the complete inability to experience anger. It’s important to understand that the “mean” (mesotēs) in Aristotle really refers to a disposition somewhere in the middle ground between two extremes. It’s not necessarily dead in the centre but at a point, relative to our circumstances, as determined by practical wisdom (phronimos). To put it another way, it’s what a wise man would choose to do and therefore avoids certain extremes. Hence, Aristotle’s “mean” may be asymmetrically related to the extremes, and closer to one end than to the other. Moreover, he does not even consistently hold that the “mean” must differ only in quantity or degree from the extremes — it is often a qualitatively different attitude or emotion.

For instance, the alternative to too much or too little anger-proneness is described in the passage above as praotes, usually translated as “gentleness”, although, as we will see this word is somewhat ambiguous and difficult to translate into English. This term was used in Greek to describe domesticated animals, as well as humans who are virtuous and even tempered. We might say, by analogy, that the praotes individual has “tamed”, “civilized”, or “domesticated” his passions, or perhaps that he is a civil human being. The established translation, however, is “gentle”. He is gentle rather than excessive and harsh. A “gentleman” as we might once have said, in English, is not prone to bouts of excessive rage, nor is he completely insensitive to wrongdoing.

Another key passage that is usually cited when attributing the doctrine of metriopatheia to Aristotle appears to clarify what he means by praotes:

The gentle person [πρᾶος] is angry at the right things, toward the right people, in the right manner, at the right time, and for the right length of time—as reason prescribes. — Ethica Nicomachea, 1125b31–35

In this passage, Aristotle clearly states that the gentle person does become angry but in accord with reason, which is sometimes taken to provide conclusive support for the claim that he endorses metriopatheia or the moderation of anger. Anger should not be eliminated but rather controlled and moderated by reason, he seems to be saying here.

That should decisively settle the debate. However, there are two problems with this interpretation. First, Aristotle appears, as we shall see, to contradict this passage elsewhere. Of course, it’s quite possible that he changed his mind or unintentionally contradicted himself. There’s a second problem with this passage, though. Aristotle famously employed a philosophical method he called endoxia, which consists in clearly describing conventional wisdom first before analyzing a concept philosophically. He often starts by describing what the majority of people believe. That’s exactly how the passage above is introduced in his writings: not as his own considered opinion but as the position adopted by most non-philosophers. Arguably, therefore, it’s meant to be descriptive not normative.

Today we would refer to this as the assumption about anger made in our common “folk-psychology”. It would therefore be circular to argue that Aristotle’s writings support the view held by the majority of people because, in fact, in this passage he may just have intended to describe what the majority of people already believe: that anger is appropriate in moderation. Moreover, even this popular definition leaves open the question as to precisely where and when anger is appropriate — and the answer, upon reflection, could be that anger is “seldom or never” appropriate.

Photo by Howard Senton on UnsplashThe Problems for Metriopatheia

Photo by Howard Senton on UnsplashThe Problems for MetriopatheiaThese two quotes, as we have seen, may appear decisive at first glance but on closer inspection leave some questions unanswered. Aristotle does not necessarily believe that praotes entails having moderate anger because it could be a qualitatively different emotional disposition — it may have some things in common with anger without actually being a form of anger. In addition, Aristotle’s description of praotes as entailing the moderation of anger in accord with reason is presented as a description of popular opinion, a starting point for reflection, rather than his own philosophical conclusion.

First of all, elsewhere in discussing his doctrine of the mean, Aristotle states that praotes, gentleness or civility, has more in common with the total absence of anger-proneness than to its excess.

The excess [irascibility] is more opposed to gentleness than the deficiency [...] gentleness is closer to the deficiency. — Ethica Nicomachea, 1126a29–b4

Even if were to accept the doctrine of metriopatheia or the moderation of anger, Aristotle appears to warn us that his ideal is more akin to the elimination of anger than to some sort of centre ground.

Moreover, elsewhere in Aristotle’s writings we find several passages that appear to directly conflict with this popular interpretation of his views on anger. Most obviously, in the Rhetoric, Aristotle famously defines anger as a desire for revenge.

Let anger be defined as an impulse, accompanied by pain, to a conspicuous revenge for a conspicuous slight directed without justification towards what concerns oneself or towards what concerns one's friends. — Rhetoric, 1378a30–33

There was more or less a consensus among ancient philosophers of different schools that anger should be defined broadly in terms of the desire for revenge. Even Seneca, who opposes the Stoic view of anger to the Aristotelian view, acknowledges that they share a very similar, if not identical, definition of anger.

Aristotle’s definition is not very different from ours: he says that anger is the strong desire to return pain for pain. (The difference between his definition and ours cannot be explained briefly.) — Seneca, On Anger, 1.3.3

Anger is essentially a desire for payback, therefore, or revenge. However, elsewhere in the text we were discussing earlier, Aristotle states that:

The gentle person is not vengeful [τιμωρητικός], but inclined to sympathetic understanding [συγγνωμονικός]. — Ethica Nicomachea, 1126a1–4

That creates a problem for the popular interpretation of Aristotle on anger. If praotes is not vengeful, and anger is essentially a desire for revenge, it appears to follow logically that the gentle person can never be angry.

Moreover, in this passage, Aristotle clearly states that, rather than being vengeful or anger-prone, the gentle person is, by disposition, sympathetic toward others and inclined to pardon their offences. In modern psychology, we typically use the word “empathy” (rather than “sympathy”) to describe what Aristotle appears to mean here, and it would indeed typically be contrasted with the psychology of anger, which is by nature remarkably unempathic.

ConclusionThese passages are problematic for the standard interpretation of Aristotle on anger, which maintains that he considered anger that is moderated by reason to be healthy. Instead, he appears committed to the view that the healthy alternative to anger, praotes or civility, completely replaces the desire for revenge with an empathic disposition, which would exclude it from his own philosophical definition of anger. He may be saying that the wise man, rather than moderating his anger, replaces it with empathic understanding, a fundamentally different attitude.

When read alongside the passages cited earlier, this could be taken to imply that the wise and virtuous alternative to both anger excessive anger and a total incapacity for anger is not a “moderate” or “healthy” version of anger but rather something qualitatively different. Contrary to Seneca, Aristotle doesn’t refer anywhere in his surviving writings to the wise and virtuous man as being moderately angry, or even to him experiencing anger at all. Instead, he makes a point of using the word praotes, meaning civility or gentleness. This appears, perhaps, to be qualitatively different from any form of anger insofar as it is empathic and non-vengeful.

It may seem puzzling why Aristotle would, then, describe it as avoiding the extreme of being totally incapable of anger — although he does say that it has more in common with this than with excessive anger-proneness. Today most people tend, by default, to think of anger primarily in terms of its intensity, something that has been called the “hydraulic” model of emotion. Research in neuropsychology universally rejects this simplistic view. Anger, and other emotions, are complex psychological states composed of different ingredients, such as physiological reactions, certain thoughts and underlying beliefs (cognitions), desires and action tendencies, as well as other feelings. Aristotle, likewise, thought of anger as a complex state of the whole psyche. It would, arguably, make no sense therefore for him to define the “mean” primarily in terms of the raw quantity of anger experienced.

Perhaps what he meant by praotes, civility or gentleness, was a state of the whole psyche that is qualitatively closer to the total absence of anger than to excessive anger. If that includes freedom from excessive anger but also freedom from the extreme of total non-anger, then it may imply that the desire for revenge has been replaced with some other desire. He doesn’t explicitly state what that would be, as far as I’m aware, but based on his claim that gentleness and civility (praotes) entails sympathetic understanding, and an inclination to pardon, he may mean that anger is replaced with a desire primarily for justice and reconciliation, rather than revenge or retribution.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 25, 2025

The Controversial History of Marcus Aurelius

In this episode, I chat with father-son team Matthew and Matteo Storm, who host the Lost Roman Heroes podcast, a bi-weekly dive deep into the overlooked lives and legacies of ancient Rome. They’re history buffs with a passion for ancient Rome. Matthew is also the author of several works of historical fiction, based in the Roman empire, the most recent being THE EMPEROR: Heraclius Battles Persia for the Life of Rome.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow did the Lost Roman Heroes podcast begin?

Travel to Carnuntum and other historic locations.

Matthew’s historical fiction set in the Roman empire

What are your favourite quotes from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius?

How can we be sure Marcus actually wrote the Meditations?

Was it intended for publication?

Why are Hadrian and Herodes Atticus notable by their absence from the list of people Marcus admires in Book One of the Meditations?

Was it really a bad idea for Marcus to appoint Commodus his successor?

Who was Avidius Cassius, the usurper?

Was Faustina the loyal wife Marcus makes her out to be or the scheming and unfaithful one depicted in the histories?

Links

LinksThanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.