Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 3

September 2, 2025

Anger: Escape from the Neurotic Paradox

In the 1960s, the psychologist O. Hobart Mowrer coined a famous term for the way in which we tend to persist in bad habits, despite the long-term suffering they cause us. He called it the Neurotic Paradox. Theoretically, we should learn from the consequences of our actions, and change our habits, but for some reason we do not. Many great thinkers have been puzzled by this over the centuries. For example, Spinoza wrote:

Human lack of power to moderate and restrain the passions I call Bondage. For the man who is subject to passions is under the control, not of himself, but of fortune, in whose power he so greatly is that often, though he sees the better for himself, he is still forced to follow the worse. — Ethica, IV, preface

Spinoza and Mowrer were right. Even today, psychotherapists recognize this basic paradox as a common factor in most emotional problems, although it can take many different forms. Of all emotions, though, the most striking example of this paradox occurs in anger. Angry people, for the most part, behave in ways they describe in the heat of the moment as "necessary” to get what they want. Later, however, when they’re no longer angry, have calmed down and are thinking more rationally, they often (but not always) look back on their anger with regret.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Cost-Benefit AnalysisTheoretically, under normal conditions, we can decide which course of action to follow by weighing up the consequences, or pros and cons, of the available options — a process known as cost-benefit analysis. This can take time to do properly. Few people are able to think through the consequences of different courses of action comprehensively on their first pass. In order to perform rational problem-solving, we have to:

Define the problem our goals, and the major obstacles, concisely and without bias

Identify the full range of potential solutions available to us

Consider the consequences of each course of action and classify them as pros or cons

Ask ourselves whether those consequences are real or imaginary, how long they last, and whether we might be exaggerating or underestimating them

Consider whether solutions could be combined or if some would be better broken down into their elements

Rank the solutions in terms of how quickly and easily they could be implemented

Select the solution with the best overall net worth by weighing the costs against the benefits

This can be a useful approach, if you have time. It can take patience, however, and in the heat of the moment most people are too angry to think through a cost-benefit analysis properly and calculate the net worth of their actions by weighting the costs against the benefits. Nevertheless, patiently reviewing the costs and benefits when you are not feeling angry, can be beneficial, if repeated regularly.

It’s usually easier to consider the short-term consequences of our actions. Evaluating the longer-term consequences, and wider impact, tends to take more time and effort. The bigger picture is often discussed during a therapy or coaching session, when you are feeling more calm and rational. By talking through and writing down your cost-benefit analysis, it can get easier to recall some of the details, or at least the overall conclusion, when you next become angry again. As we shall see, there are techniques that can help you to do this by bridging the gap between your calm and rational mode of thinking and your angry mode of thinking.

Consequence BlindnessWhen we become angry, our brain enters a different state, which cognitive psychologists call the hostility mode. The fight-or-flight response is triggered, changing our body’s physiology, but, more importantly, our brain begins to function differently. Non-conscious implicit “cognitive schemas” are activated, which are deep-seated clusters of beliefs that shape our feelings and behaviour, centred around themes such as threat and helplessness. Our prefrontal cortex becomes less dominant and the limbic system hijacks our thinking, which becomes heavily biased in ways that significantly impair our capacity for rational decision-making, problem-solving, and empathic understanding. We find it particularly difficult to evaluate the longer-term consequences of our actions as the red mist descends.

This is highlighted by the frequency with which angry people later, when no longer angry, express regret for their actions. What seemed like a good idea at the time, or the only option, no longer seems like it was the right thing to do. This temporary blindness to consequences is closely-associated with other well-established characteristics of anger. Research consistently shows that angry people tend to behave more impulsively and recklessly. Cognitive studies have shown that whereas anxious people overestimate risks, anger tends to make us underestimate risk, which can even mean that we place ourselves and other people in danger. People who are most prone to anger, therefore, have more accidents than average, and their life expectancy tends to be shorter. In extreme cases, they are more likely to engage in risky behaviour, and get themselves injured or even killed.

Plato had a great analogy for this. Someone armed with a sword can potentially kill anyone he pleases — he is armed and dangerous. That may give him a sense of power or control. Imagine, however, that he is blindfolded. He is dangerous but, in a sense, powerless, because he has no idea whether he is stabbing his friends or his enemies. He can cause harm but lacks insight into the consequences of his actions — he’s just waving a sword around blindly. Later, when the blindfold is removed, he may regret his actions. When your brain enters the hostility mode, you get a surge of adrenaline and may even have more physical strength and energy, but your judgment is severely clouded. During anger you become like a blindfolded swordsman.

SimplificationOn the occasion of every act ask yourself, “How is this with respect to me? Shall I repent of it?” — Meditations, 8.2

One solution is to simplify and condense the process of decision-making so that it uses less time, energy, and mental bandwidth (“cognitive load”) during episodes of anger. If we don’t have time for rational problem-solving and rigorous cost-benefit analysis we can potentially find a “quick and dirty” form of decision-making, which still functions adequately under heightened stress and time pressure. You may have to be able to do something very simple if you’re going to regain your self-awareness quickly enough.

For example, we can use a technique called “time projection” to simply imagine ourselves looking back on our anger and aggression from a time in the future, when we’re no longer angry, and imagine, for a moment, whether we will regret what we were about to do. That can be done quite quickly by asking ourselves a question such as one of the following:

Will I regret this later?

How will I feel about this when I’m no longer angry?

What will I make of this looking back on it, one day, in the future?

There’s another very powerful question, which I have found people can quite easily ask themselves even in the heat of the moment.

What does me more harm: my anger or the thing about which I'm angry?

That question can be answered in two different ways. The first is simply by considering whether the consequences of getting angry are more harmful than the situation about which you’re angry. The other requires adopting a slightly more philosophical perspective by asking yourself whether anger might be intrinsically harmful, regardless of its consequences, because it’s inherently incompatible with your core values, and the type of person you want to be in life. We can refer to that as shifting our orientation from external goals toward internal ones, or adopting a values orientation.

Values OrientationAbout what am I now employing my own soul? On every occasion I must ask myself this question, and inquire, “What have I now in this part of me which they call the ruling principle? And whose soul have I now? That of a child, a youth, […] a tyrant, a domesticated animal, or a wild beast?” — Meditations, 5.11

Anger, as we have seen, specifically impairs our ability to think about the consequences of our actions, especially the longer-term consequences — and it makes it difficult to perform more demanding calculations such as weighing the costs against the benefits. However, thinking about the consequences of our actions is not the only way that humans make decisions. Although many people take it for granted that this is how decisions should be made, in fact, others simply consult their values and principles instead.

Of course, these two perspectives are not mutually exclusive, we can potentially combine them. However, when we’re under emotional stress, our attention is narrowed, and our mental bandwidth is significantly reduced, we may find it much more efficient simply to ask ourselves:

How does my anger and aggression right now accord with my core values?

Is this really the type of person that I want to be in life?

What sort of person have I become right now? Is this what I want my life to be about?

Here we are specifically referring to valued character traits or what ancient philosophers called the virtues. They’re also the qualities you tend to admire most in the character of other people.

Of course, the problem with this approach is that most people don’t have any values. More accurately, they don’t know what their values are, or they have very vague and abstract values. That can easily be resolved by spending some time clarifying your values when you are feeling calm and relaxed, and writing down concise notes on their personal meaning for you. In reality, most people tend to identify surprisingly similar values. The cardinal virtues of Stoicism were wisdom, justice (including kindness), temperance, and fortitude. Most people value wisdom, and these other traits, but the words probably have a slightly different connotation for everyone. Ask yourself how you would label the character traits you most value, and then explore what their personal meaning is to you.

This process can go on for a lifetime. However, spending even ten minutes doing it will usually make it much easier for you to consult your values in real situations. Even if the answer is not conclusive, that doesn’t matter. The big problem occurs when you’re completely unable to consult your values because they’re so vague that you can’t connect with them even a little. In my experience, most people can interrupt anger, in the heat of the moment, simply by pausing to ask themselves: “How does this align with my core values?”

It’s works even better if you can reference specific values. For example, you might say “How does getting mad right now square with the value I place on being a patient human being?” or “Is yelling at my kids a form of temperance or is it the opposite?” or “How is it just of me to rigidly demand that other people do what I want?”, and so on. Think of the type of person you want to be in life and ask yourself, when you notice anger starting to appear, whether it’s in accord with those values or not. You may even be able to activate your values orientation with a single word or phrase, lightening the cognitive load while nevertheless snapping yourself out of the trance of anger.

In Nikos Kazantzakis' novel Zorba the Greek, the central character is an unusual man who ridicules the whole idea of decision-making by rational calculation, or cost-benefit analysis. Zorba laughs at his English friend, and boss, for overthinking everything.

You think too much. That is your trouble. Clever people and grocers, they weigh everything. — Zorba the Greek

Zorba lived completely in the moment. He valued integrity, resilience, and courage. Critics see him as excessively childlike because of his extreme spontaneity. However, he illustrates an alternative way of life, which does not depend upon weighing up the consequences of every action, but is not completely reckless either, because he is guided by certain values.

Nobody views Zorba as a role model. We’re told did some terrible things earlier in his life, and he makes some reckless decisions in the novel. He perhaps lacks certain values. However, there is something appealing about him. He shows us that it may be possible to live well without having to weigh every decision in the moment. The Indian mystic and philosopher, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, used to say that he called his ideal was “Zorba the Buddha”, someone who combined the wisdom of Buddha with the freedom and vitality of Zorba. If you can be fully present in the moment, but allow your core values to guide your actions, you may be able to combine wisdom and immediacy. Learning how to act wisely without having to think too much, by getting clearer about your values, is often our best defense against anger.

What do you do, though, instead of what anger is telling you to do? The basic strategy for dealing with anger is postponement, or doing nothing, until our anger has naturally abated, and we can think calmly and rationally once again. However, if you have to take action, rather than trying to plan what you’re going to say and do systematically, it’s often quicker just to ask yourself what would way of behaving be most in accord with your core values. Acting in accord with your values usually takes effort, but it may be less effort than trying to engage in rational problem-solving, while you’re still feeling the effects of anger.

Look over this article, and consider the simple questions mentioned above. What would happen if you ask yourself these things in order to nip anger in the bud? Could you even focus on these sorts of questions before, during, and after episodes of anger — to really drive home the new mind-set? Please comment on this article and let me know what you find the most helpful things to say to yourself when you notice that you’re beginning to get angry unnecessarily. It’s often useful to read about other people’s coping strategies. What works, in many cases, is very simple, and may even appear like common sense, but we often don’t see the wood for the trees when it comes to self-improvement, and we can gain confidence and focus by learning how other people succeed in coping with similar problems.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 28, 2025

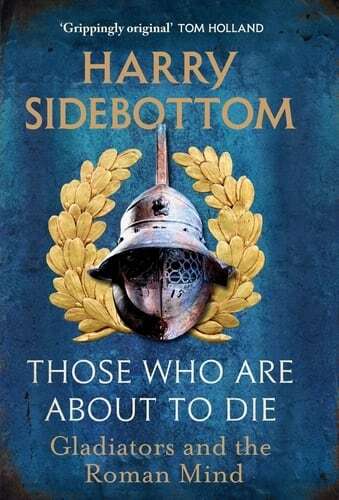

A Day in the Life of a Roman Gladiator

In this episode, I chat with Harry Sidebottom. Harry is a Lecturer in Ancient History at Lincoln College, Oxford. He is the bestselling author of fifteen historical novels, and nineteen books in total. His debut trade non-fiction book, The Mad Emperor: Heliogabalus and the Decadence of Rome, was a Book of the Year in the Spectator, the Financial Times and BBC History. His latest book, Those Who Are About to Die: A Day in the Life of a Roman Gladiator is published in the UK on the 28th Aug, and in the US later next year.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsGladiators capture the public imagination but what did you want to explore the Roman mindset by focusing on them?

What does the institution of gladiatorial games tell us about Roman views on life and death?

What do you think it may surprise your readers to learn about the world of the gladiators?

What are the differences between the fighting skills of a gladiator and a legionary?

What were the strangest animals they fought or hunted in the arenas?

As a historian who has deeply studied the Roman mind, what have you learned about their core values? And how do you think those compare to our modern sensibilities?

From your research, what can the Romans teach us about resilience in the face of adversity?

Links

LinksThose Who Are About to Die (Penguin)

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 26, 2025

Stop using Fear to Motivate Yourself

Photo by Hamed Taha on Unsplash

Photo by Hamed Taha on UnsplashOne of the most common problems I encounter with clients is that they’re using fear to motivate themselves. Put simply, that’s what you’re doing when you tell yourself horror stories about how catastrophic the outcome will be if you don’t work much harder and perform much better in the future.

For example, “I absolutely must pass this exam, because failing is not an option for me!” Many people are convinced that this is the only, or at least the most efficient, way to “get things done”, as they often put it. However, in some cases it can become problematic and may even backfire. Those people who tell themselves they absolutely have to achieve certain things, or must not fail in their endeavours, are often the ones most obviously struggling, and driving themselves crazy. So what’s going wrong?

The desperate need to achieve success can lead to rigid demands such as:

I must work far harder!

I should never make mistakes!

I always need to be better than everyone else!

I have to succeed!

My work has to be perfect, or at least meet an exceptionally high standard!

How are you going to force yourself to work ten times harder, though, never make mistakes, be better than everyone, and always succeed? That sounds pretty demanding, right?

“I have to be terrified of failure, if I want to be motivated enough to achieve success.”

Well, the crudest and most obvious solution would arguably be to put the fear of God in yourself by absolutely drumming it into your brain that any sort of failure would just be an unmitigated disaster! If you can convince yourself that the alternative to working like crazy would be suffering an unbearable catastrophe, then you’re going to feel terrified of failure and you’ll work your backside off to avoid it happening, right? You might even believe: I have to be terrified of failure, if I want to be motivated enough to achieve success.

You rot your life away and what do they give?

You're only killing yourself to live! — Black Sabbath, Killing Yourself to Live

Telling yourself that you must achieve some goal often goes hand-in-hand therefore with telling yourself that it would be unthinkably bad if you failed. We hype up the costs of failure for ourselves by focusing as much as possible on the worst that could possibly happen, replaying that clip in our mind, and exaggerating the probability and severity of the worst-case scenario. We can also amplify our fear of failure by downplaying our ability to cope with the consequences. “What if I fail? That would be awful! How would I cope?” Psychologists call this catastrophizing.

If we catastrophize the consequences of failure, we can sneakily motivate ourselves to try harder by, well, making ourselves petrified of failure. The fear causes our bodies to produce adrenaline and other stress hormones and that gives us a rush of nervous energy, which it’s tempting to use in order to “get things done”. It’s like constantly revving the engine of your car. Already, you might be thinking this doesn’t seem like a healthy long-term strategy to employ in life. You’d be surprised how common it is for people to do precisely this, though. We all do it to some extent.

It’s a foolproof plan, right? What could possibly go wrong? Well, perhaps beating yourself relentlessly with the stick of abject fear in order to get yourself to work could have some drawbacks further down the line. First of all, though, does it at least work in the heat of the moment? Well, yes and no. Focusing on how catastrophic failure would be will, for sure, get your heart pumping. It will release adrenaline, which will give you a surge of energy and motivation. We also tend naturally to focus our attention narrowly on perceived threats, so you’ll find it easier to concentrate at first. As the writer and wit, Dr. Samuel Johnson, notoriously put it:

Depend upon it, Sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.

Scaring the living daylights out of yourself is certainly one way to get up and out of bed early in the morning, in order to get some work done. Focused attention, and the adrenaline rush, are the main benefits of this approach to life. You have to ask yourself, though: is it doing you more harm than good?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The DownsideThose are typically the perceived advantages of using fear to motivate yourself. It’s worth asking whether they’re real or illusory, though. Does it really motivate you to work harder or only feel like it’s doing so? Do you actually do better work this way or get more accomplished? Are the benefits, such as the burst of adrenaline, temporary or durable — exactly how long do they last?

Well, let’s get specific… The initial surge of adrenaline following exposure to our fears normally lasts less than one hour. In reality, when it’s triggered by worrying or anticipatory fear, rather than facing our fears in reality, it’s usually much shorter, say, less than half an hour — and sometimes so fleeting it may only last a few minutes. The adrenal glands release the hormone into your bloodstream, it’s then actively broken down by your liver and kidneys, so that the body can return to homeostasis, and the remnants are excreted in your urine.

After the initial adrenaline rush, if we continue to perceive an ongoing threat, the acute response turns into the chronic stress response as adrenaline fades and cortisol starts to take over. This basically just makes you feel rough, rather than actually motivating you to work harder. In fact, fatigue, lethargy, brain fog, poor concentration, and a loss of enthusiasm tend to follow as consequences of chronic stress.

In other words, you can’t just keep triggering the anxiety response all day long. You have roughly half an hour or so of adrenaline each time, if you’re lucky, followed by its more toxic consequences. You can try focusing on the worst-case scenario later in the day but doing so will fall foul of the law of diminishing returns because your body responds by inhibiting its reaction to adrenaline. In short, if you keep trying to fire your adrenal glands, by repeatedly worrying about failure, you're asking for a surge of power from a system that has now placed itself in damage control mode.

I have some more bad news for you: your feelings aren’t entirely under your control. So the adrenaline boost you get from fear is likely to fluctuate depending on all sorts of arbitrary factors, from how well you slept, to what sort of lunch you had, and perhaps even the weather. Emotions are a notoriously fickle and unreliable source of motivation. You’ll go from being a raging workaholic one day to sulking under the bedcovers the next because to some extent your feelings come and go, well, whenever they feel like it.

Just to add to that, it’s well-established that anxiety tends to abate naturally over time through a process called emotional habituation. So the surge of energy you get from worrying about specific problems, even if it works okay at first, is likely to wear off over time if you do it too often. Normally that’s a good thing — it’s a natural and highly adaptive feature of emotional processing. But if you’re hooked on adrenaline, and believe that you need fear to avoid catastrophic failure, it’s going to feel like withdrawal, or at least as though you’re somehow vulnerable unless you relentlessly keep your guard up and keep working harder. You’re going to have to get creative in your worrying, forcing your mind to keep circling around different aspects of same problem, or jumping from one problem to another, just to keep getting your adrenaline fix. Genuinely successful people, in fact, don’t rely on their feelings, and certainly not anxiety, to get work done. They use their goals and values to provide a more stable and consistent source of motivation.

One of the difficulties with using anxiety as a source of motivation is that, apart from the fact that it fluctuates naturally, anxiety can be alleviated in many different ways. So we are provided with endless shortcuts that allow us to relieve our anxiety without accomplishing our goal. These range from drinking whisky to reassurance seeking, from distraction to taking a nap, from sex to rationalizing the problem. There are countless opportunities for us to “cheat” by temporarily damping down or neutralizing our anxious arousal. The more you rely on fear, in other words, the more appealing procrastination become, over time, and the more compulsively you may find yourself avoiding work.

Next, it’s worth asking yourself what the costs or disadvantages of using fear to motivate yourself might be.

What effect does it have on your mental and physical health?

How might it interfere with or impair your performance at work?

What impact could it have on your relationships — with friends, family, colleagues, and even strangers?

How does it affect your self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-image?

What effect does living this way have on your daily routine and overall quality of life?

Crucially, you should consider not only the short-term consequences of using anxiety to motivate yourself but also the longer-term. How is it likely to work out for you in the long-run? Weeks, months, and even years from now, where is this strategy probably going to lead you?

Finally, and most importantly in my experience, you should ask yourself whether motivating yourself in this way might, ironically, backfire on you by achieving the complete opposite of what you want. Like throwing gasoline on a fire in order to put it out, could it be that your solution is actually just making your problem even worse?

Could it be that using anxiety to motivate yourself backfires by interfering with your ability to focus on certain ideas and perform certain tasks? For example, does it make you distracted or physically and mentally tense in ways that harm your performance?

Could the stress make it harder for you to handle complex tasks or find more nuanced solutions to problems? Does it make your thinking and behaviour become more rigid and inflexible in ways that undermine your ability to think clearly and adapt to the challenges you face?

Might this strategy backfire increasingly if you rely on it too much and for too long? Could an extreme aversion to failure cause you to worry, procrastinate, avoid thinking about problems, and put off important tasks? What if all that adrenaline leads to fatigue over time and, eventually, to burnout?

One of the most powerful ways to challenge this type of pattern is to focus your attention on the insight that your fear of failure may actually be the very thing that’s preventing you from succeeding. Trying too hard to succeed, is a sure road to failure. It’s the opposite of what you want. The more you want to succeed, the more you should be challenging your rigid demands and fear of failure because, ironically, they’re precisely what’s standing in your way.

Photo by Sean Benesh on UnsplashThe Alternative

Photo by Sean Benesh on UnsplashThe AlternativeHow do other people manage to succeed without using fear to motivate themselves? Stop and really think about that for a while. Some of the most successful people in the world are able to do without this strategy. Not everyone is driven by anxiety. The main advantages of a non-anxious attitude are that you’ll be more flexible and adaptive. Someone who is unafraid of failure will be able to accept what initially feels like a setback or looks like failure, and take it in their stride. They’re willing and able to go one step back, if it allows them to take two steps forward. What if that is precisely the secret of their success?

Imagine a great writer or musician who is able to endure criticism because they know that it’s inevitable when you create something truly original. What about a great general who is willing to sacrifice positions, and make tactical retreats from some battles, in order to win the war. Boxers may take some punches in order to win the fight. In chess, you have to be willing to sacrifice some pieces to win the game. To get through a maze, you might have to be willing to backtrack sometimes in order to find the way to the exit. A successful businessman may be one who is willing to take certain risks and accept certain losses, in order to secure bigger goals. How will a student ever learn if they’re not willing to make mistakes? If you are rigidly perfectionistic and terrified of losing, you will be unable to accept temporary defeats, or the appearance of failure, in order to achieve longer-term success.

A better philosophy would be one that says “I really love doing well and succeeding, it’s really important to me, but setbacks aren’t the end of the world, I can cope with them, and they can even be a positive thing if I can learn from them.” Ask yourself whether you could get all the benefits of using anxiety to motivate yourself, with none of the costs. Rewarding yourself for progress and taking pride in your work is a much healthier and more flexible way of motivating yourself in the long-run.

Perhaps most importantly, look deeply into your heart and ask yourself what your core values are. What sort of person do you want to be? What do you want your life to stand for? Perhaps you value wisdom, kindness, fairness, courage, or self-discipline. Then ask yourself whether using anxiety to get things done is consistent with your own values — is this the type of person I want to be in life? What would you do instead, then, if you were acting more consistently in accord with your true values?

DecatastrophizingFinally, it’s worth asking yourself whether “failure” would necessarily be as awful as you like to assume. Are you just frightening yourself unnecessarily by catastrophizing failure?

Could you be exaggerating the severity of the problem?

Might you be exaggerating the probability of the worst happening?

Are you underestimating your ability to cope, survive, and even learn from your failures?

How many of the things you’ve worried about over the years actually happened and were as bad as you assumed they would be? Learn to view problems as opportunities. How else would you become stronger and more resilient if not by experiencing setbacks and learning to get through them?

Ask yourself bluntly, “So what if I fail? Would it really be the end of the world?” How bad would it really be on a scale from 0-100, where 100 is, say, global nuclear apocalypse, genocide, or maybe suffering the most extreme form of medieval torture? On the scale of worst things imaginable, where is failing an exam, or failing to deliver on time for a contract at work? Probably nowhere near the top, right? And “this too shall pass” — it won’t last forever…

But you can go even further. You could make an effort to counteract your catastrophizing bias by focusing on the positive aspects of failure. You may quickly be surprised to realize something — they’re usually easy to spot. If you approach failures in the right way, as temporary setbacks, not as problems but as challenges or opportunities, you will cope well, and may even grow wiser and stronger as a result. In fact, how else do you think people become resilient? By living in luxury and always succeeding at everything they do? You need some problems, otherwise, frankly, you would die of boredom. See them for what they are, though. Not “catastrophes” but the sort of obstacles that countless other people have also faced, coped with, and survived, throughout their lives.

ConclusionIt’s very common for people to use fear to motivate themselves. It just doesn’t work very well, though, especially in the long run. So why do we do it? Probably because we learn this bad habit from our parents and teachers as children, when they try to frighten us into trying harder at school, and so on. Sometimes it happens because we experience a traumatic setback, and we use the memory to try to scare ourselves into working extra-hard so that it never happens again. Mostly, though, we use the fear of failure to make ourselves do things because it’s so easy. In the art of motivation, it’s the quick and dirty solution. It’s basically the crudest and most simplistic coping strategy at our disposal.

It’s also a bit addictive. We become hooked on the short-term relief that comes from working harder when it temporarily alleviates the pain of anxiety, which we inflicted on ourselves in the first place. It’s sticking a bandaid on a self-inflicted wound. There are better ways of building motivation, such as positive reinforcement and connecting our actions with our core values. They start from the realization, though, that coming to rely on fear actually does us more harm than good.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 19, 2025

Deep Cognitive Disputation of Rules

One of the basic techniques of cognitive therapy involves identifying irrational thoughts and asking yourself: Where’s the evidence for that? Passing thoughts tend to reveal more stable underlying beliefs, which usually become the main focus of therapy over time. There are many techniques that can assist us in evaluating the evidence for and against our own troubling beliefs. It’s also helpful to evaluate the “pros and cons” of beliefs that take the form of implicit or explicit rules. For example, “I must always control my emotions”, “People have to respect me” or “Life should be fair.” These rules, or rigid demands, often appear central to our emotional problems — hence therapists often refer to them as The Tyranny of the Shoulds.

Photo by Edge2Edge Media on Unsplash

Photo by Edge2Edge Media on UnsplashOne of the most common techniques for challenging such beliefs consists in drawing two columns, often on a flipchart, used to list the “pros and cons” of the belief. Some clients will, at first, only list the disadvantages (“cons”). This can be misleading. The fact that they believe it at all, let alone so strongly, when upset, suggests that there must be some reasons why it appears helpful or necessary to accept this rule in the heat of the moment. It’s particularly important to root out those hidden reasons for clinging onto an unhelpful way of thinking, so that they can be subjected to more careful evaluation.

However, it’s one thing to realize, in retrospect, that our beliefs and actions are not helpful. It’s another to really grasp that in the heat of the moment. If you can learn to notice when a belief is active and simultaneously perceive it as worthless and self-defeating, you will loosen its grip on your mind and you will typically also weaken its effect upon your emotions. That comes from repeatedly disputing the irrational belief in the right way, until an alternative perspective becomes habitual and second nature to you. That’s made easier if the disputation is both powerful and concise.

It’s not just false, it’s the opposite of the truth.

It’s not just unhelpful, it’s the opposite of what you want.

In this article, I want to focus on what I consider to be one of the most effective ways of challenging a rule or “should”. That consists in drawing attention to the fact that, in ways you previously overlooked, your belief may actually be self-defeating. It’s not just false, it’s the opposite of the truth. It’s not just unhelpful, it’s the opposite of what you want. These sorts of rules attempt to solve a problem, but actually make it worse. You’re trying to fix things, but actually breaking them more and more. Like throwing gasoline on a fire to try to put it out. Like trying to dig your way out of a hole, and just getting stuck deeper and deeper. Or trying to free yourself from a net, only to make yourself more entangled the harder you struggle. These sorts of rules are a trap.

The fact that we often persist in ways of acting that are obviously doing us more harm than good, used to be known in psychology as the Neurotic Paradox.

Why do we Have Irrational Beliefs?First, I want to discuss some of the reasons why a belief might seem convincing when we’re highly emotional, even if it seems irrational to us later, when we’ve calmed down. As the philosopher Spinoza once wrote:

Human infirmity in moderating and checking the emotions I name bondage: for, when a man is a prey to his emotions, he is not his own master, but lies at the mercy of fortune: so much so, that he is often compelled, while seeing that which is better for him, to follow that which is worse. — Ethica, IV, preface, my italics

The fact that we often persist in ways of acting that are obviously doing us more harm than good, used to be known in psychology as the Neurotic Paradox. It’s one of the central challenges for self-improvement.

To help shed some light on this anomaly, it may be useful to repeatedly ask yourself these two questions about a specific belief (e.g., “I must always succeed”):

When I’m most upset, or the last time I became upset about this, how strongly did I believe this, from 0-100%?

Now that I’ve no longer upset, how helpful, objectively speaking, is it to hold this belief, rated from 0-100%?

We sometimes call this the difference between “hot” and “cold” cognitions. Noticing the difference between what you believe when emotional versus what you believe when feeling calm and rational is the easy part for most people. Now comes a harder question. Assuming you rated the first question higher: why are those numbers different?

That’s a difficult question. Most people tend to say, at first, “I don’t know.” They might say “Because it feels more believable when I’m upset” or “Because it feels necessary sometimes”. That’s a circular explanation, though — it doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know. The big question is: Why do these rules seem more believable or more necessary, when you’re upset and less believable when you’re not upset? There are several possible answers. One that I find useful is that when we become highly emotional our awareness tends to become more narrow in scope and focused on potential threats.

This leads to a bias called selective attention. We behave as if we’re dealing with a crisis and ignoring extraneous information, we focus exclusively on the perceived problem. That may be useful in a real emergency. However, it comes at a great cost. Selective thinking, during heightened emotion, tends to make us ignore certain evidence relating to our beliefs and to ignore some of the consequences of our actions. In particular, emotional stress can temporarily inhibit thinking about the longer-term consequences of our actions.

That can narrow focus can make beliefs seem convincing in the heat of the moment, which seem very unconvincing when we’ve calmed down and are able to consider the consequences of our rigid rules in a more balanced way. To put it simply, we tend to forget all of our reasons for adopting healthier attitudes when we’re highly emotional and our attention becomes focused on our immediate problem. That leads to other cognitive biases such as:

Exaggeration, because we ignore conflicting evidence

Overgeneralization, because we ignore the exceptions to our belief

Unfounded assumptions, because we ignore alternative possibilities

We can list the evidence against a belief or negative consequences of holding it in more detail when we’re feeling calm and rational. We can repeat this exercise many times, write down our reasons for rejecting an irrational belief, discuss them with a therapist, repeat them aloud, condense them, and integrate them more deeply in other ways, so that we’re more likely to remember them even when we become highly emotional. In this way, we can gradually change the unhelpful beliefs that become activated, even during intense depression, anger, or anxiety.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Cost-Benefit AnalysisLet’s focus on evaluating the “pros and cons” of a rule — sometimes called cost-benefit analysis. There are three main ways in which this may weaken your level of belief.

If you identify more costs or disadvantages (“cons”) than before, or you come to believe they are more serious than before.

If you start to question whether some of the perceived benefits or advantages (“pros”) are real.

If you conclude that the perceived benefits are not only illusory but that holding the belief actually achieves the opposite.

Of all the reasons that we can muster against holding an unhealthy belief, this third type may be the most powerful: evidence that it is actually self-defeating. By that, I mean that even the residual motives that we have for holding a belief are false and, in a sense, the opposite is true. Put bluntly, in many cases, we find that the perceived benefits of a belief are not only illusory but holding the belief actually achieves the opposite. Let me give you some examples:

“I have to drink alcohol to relax in social situations” — But what if, in the long-term, it turns out that it actually does the opposite by fueling your social anxiety?

“Yelling at my kids is the only way I can get them to listen to me” — What if over time that causes them to lose respect for you, though, and to question your authority?

“I must worry about my problems to cope with them” — What if worrying clouds your judgment, stresses you more, and actually makes you much worse at solving problems?

“I must strive for perfection if I want to avoid failure” — What if it does the total opposite by leading to greater fatigue, procrastination, and avoidance over time?

“People must respect me” — What if rigidly demanding respect from others too rigidly actually backfires by making them lose respect for you?

“I have to ruminate about the causes of my depression to find a solution” — But what if dwelling on the problem is actually making you more depressed?

Really drawing your attention to the fact that a course of action does the opposite of what you want is a very powerful way of weakening your belief in it. We can call these sorts of rules paradoxical because they are ultimately self-defeating. Ironically, the harder you try to make things better, by following these sorts of rigid rules, the worse they tend to become. You’re basically just digging yourself into a deeper hole. They’re not just unhelpful — it’s worse than that — they’re profoundly self-defeating. It’s as if you’re trying your hardest to get somewhere in life with these rules but they’re taking you in the opposite direction.

Spotting Paradoxical BeliefsThere are a couple of questions which can help you to spot the counter-productive nature of certain beliefs or actions:

Does this belief feel or appear as if it’s doing one thing while actually doing the opposite?

Does this belief potentially make the very problem it's trying to solve worse rather than better?

These additional questions may help you dig even deeper into the counter-productive nature of your beliefs:

Does it benefit you in certain situations but backfire in most others, thereby achieving the opposite overall?

Does it benefit you in a limited way but prevent you from doing something that would potentially be more beneficial?

Might your belief potentially affect other people in a way that is the opposite of what you want?

Does it seem to benefit you in the short term but actually do the opposite over the long-term?

Let’s apply those to a common example: “I must always get things perfectly right to avoid a catastrophic failure” or “My perfectionism motivates me to work harder and thereby helps me to succeed.”

Perhaps it feels like your perfectionism is helping you to succeed but, objectively speaking, if you think about it, you’re less successful than other people who have more flexible attitudes.

Perhaps your rigid perfectionism causes you to make more mistakes than normal, or avoid learning from harmless mistakes in a way that would help you to make progress.

Perhaps it works for certain simple short-term tasks but backfires dramatically when you try to apply that level of perfectionism to more complex situations where greater tolerance of mistakes would make more sense.

Perhaps it does motivate you to some extent but coming to depend on it too much has actually prevented you from developing healthy and flexible motivational strategies that would help you to succeed more consistently.

Perhaps it motivates you to succeed in the short term but leads to greater frustration and fatigue in the long-term, which undermines your motivation, and causes subtle avoidance and procrastination, which can backfire and lead to failure.

Sometimes it’s obvious that a belief or action is backfiring, like you’re trying to put out a fire by dousing it in gasoline. Often, though, it’s a bit more subtle, and you may need to think carefully about how your efforts at a solution could be making the problems worse.

ConclusionIt’s easier to notice how other people’s rigid beliefs may backfire dramatically. You probably have probably met someone who tried way too hard to be your friend and actually drove you away as a result. You may notice people desperate to control a situation, who end up making it worse and causing more chaos. The world is full of people who wanted so badly to succeed that they inevitably failed. We all try too hard sometimes, and end up achieving the opposite of what we want. Usually that’s because we’re approaching things in an overly-rigid way, rather than being flexible and adaptive enough in our approach.

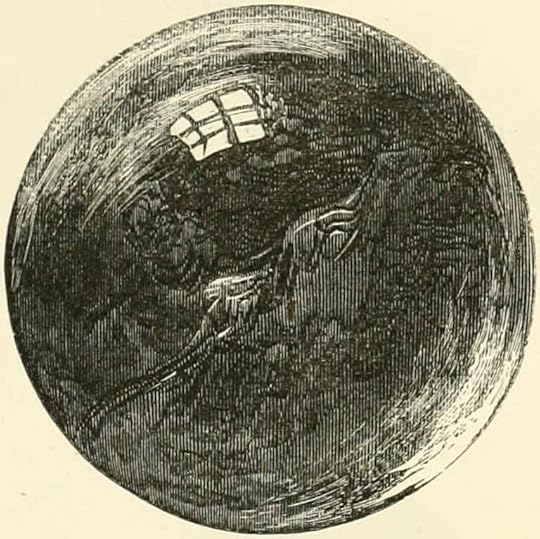

As the philosopher Wittgenstein put it, therapy consists in showing the fly the way out of the fly-bottle. The early 20th century flytrap design he probably had in mind is shown in the photo below. It’s a great illustration of the Neurotic Paradox. Flies are drawn to the bait inside the glass bottle, entering through the hole in the bottom. They get stuck because they instinctively fly upwards to escape threats — “I must fly upwards or else I will die!” They keep banging against the top of the glass, trying harder and harder to escape, until they become exhausted and die in the bottom of the bottle. Flying upwards usually works, but not in this situation. Their rigid “rule” about how to escape danger is, ironically, precisely what kills them in the end.

Realizing that your rules are backfiring and getting you the opposite of what you want potentially forces you to reconsider the perceived benefits that motivated you to cling on to that way of thinking. You’re in “psychological quicksand”, and the more you fight and struggle to get out, the deeper you’re sinking. It would be better for you to pause and give yourself a moment to think of an alternative solution.

You often have to see this happening in the heat of the moment, though, in order to really shatter your belief in the old rule. It’s not just that it’s not working. That might lead you to think that instead of replacing it with a more flexible way of thinking, you should just try harder, more forcefully, or more aggressively to apply your rigid rule: “Try doing more of the same!” But the more effort you make to follow these paradoxical rules, the more they’re going to blow up in your face. Spot the self-defeating nature of your beliefs in the heat of the moment, really focus your mind on the insight that they’re not helping, and back yourself out of the trap created by these paradoxical rules.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 18, 2025

You are invited to: The Philosophy of Love and Relationships

I’m proud of my wife, Kasey, for taking on the responsibility of organizing our next Plato’s Academy Centre virtual conference. Kasey and her co-author, clinical psychologist Scott Waltman, are currently working on their latest book, which will be about Stoicism and cognitive-behavioural therapy self-help for relationships. She has put together an amazing program of speakers for the event, which is called The Philosophy of Love and Relationships.

This is a free event, although donations are welcome — as they help us to continue doing similar events in the future. Everyone is welcome, and don’t worry if you’re in a different time zone — a full recording will be sent to everyone who registers in advance.

My aim is practical: it is to extinguish cruel flames,

and from love's fetters to free the captive heart. — Ovid, Remedia Amoris

We’ve been thinking about running an interdisciplinary event of this kind for a few years now. So it’s great to see it finally happening. We’re sure the experts will give you a wide range of insights in the the challenges we face in love and relationships, including some valuable practical advice. We’ve invited a range of academic philosophers, classicists, and psychologists to present.

Speakers include:

Prof. Michael Fontaine, author of How to Get Over a Breakup: An Ancient Guide to Moving On — based on the famous Remedia Amoris of the Roman poet Ovid

Dr. Helen Marie, author of Choose You — an expert on trauma, attachment, and relationships

Prof. Armand D'Angour, author of Socrates in Love and How to Talk about Love — an ancient guide for modern lovers, based on Plato’s masterpiece the Symposium

Dr. Kore Nissenson Glied and Anna White, co-hosts of The Type C Personality podcast — experts on helping people-pleasers overcome burnout

And many more…

Please share this message with any friends who you feel may be interested in The Philosophy of Love and Relationships.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 16, 2025

The Forgotten Virtue of Magnanimity

One of the greatest shortcomings of conventional self-help and psychotherapy is that they are inherently problem-oriented. People seek therapy because they feel something is going wrong for them. That applies to many problems but in this article I’m going to focus exclusively on anger. People come to therapy because they want to control their anger. At first, though, they’re often very unclear about what the alternative to anger would look like. There are reasons to believe that adopting a more positive values-oriented outlook can actually help you to cope better with emotions such as anger. By that I mean a perspective that focuses on the value of specific character traits, of the sort that ancient philosophers, such as the Stoics, referred to as the virtues.

Photo by Sylvain Mauroux on Unsplash

Photo by Sylvain Mauroux on UnsplashSeveral of the classical virtues are relevant to the problem of controlling your temper, such as wisdom, fairness, kindness, courage and, perhaps most obviously, temperance. However, in this article, I’m going to discuss a less well-known virtue. In a sense, it’s the forgotten virtue, because we no longer have a word for it in English. It was, however, once a very familiar and extremely important concept to ancient Greeks and Romans. In Greek, it’s called megalopsychia and in Latin magnanimitas, from which we derive the English word magnanimity. This is how we currently define it:

magnanimity. The quality of being magnanimous: loftiness of spirit enabling one to bear trouble calmly, to disdain meanness and pettiness, and to display a noble generosity. — The Merriam-Webster dictionary

This is how megalopsychia is defined in an ancient dictionary of philosophical terms.

megalopsychia. Nobility in dealing with events; magnificence of soul, together with reason. — The Definitions, Pseudo-Plato

You might think those are pretty similar definitions. So what’s missing? As is often the case, the Greeks and Romans were more aware of the most literal meaning of the word, in addition to the denotation given by this dictionary definition. Megalopsychia and magnanimitas, as you might be able to infer, both meant having a big psyche or animus — a great mind or soul.

Ancient philosophers were very aware of this literal meaning, and that is precisely how they used the word. The Stoics, for instance, actually believed that the psyche can become bigger or smaller, lighter or heavier. For example, we’re told the early Greek Stoics defined emotional suffering as “an irrational contraction of the psyche”, which takes various forms (Diogenes Laertius, 7.1.111). The Stoic Sage, incidentally, never experiences emotional suffering, we’re told, because his mind does not contract (Diogenes Laertius, 7.1.118).

That might sound overly metaphysical today. However, we do know that attention can become broad or narrow, flexible or rigid, which perhaps comes close to what the Stoics intuitively recognized and expressed in their own way. When someone gets angry their attention tends to narrow and become rigidly fixed on the perceived threat or problem. When someone is unperturbed by insults, and so on, we may therefore expect the opposite. Their attention remains broad and flexible, and the problem, though not avoided by them, seems to occupy only a small corner of their mind.

In modern-day English, we no longer use the word “magnanimity” with its original literal meaning in mind. It no longer means having a big mind or soul. And, in any case, it’s no longer a word that’s commonly used. There are, however, still fragmentary traces of this concept found in various idiomatic expressions in use today. People sometimes say that, rather than becoming angry at a perceived offence, we should be “bigger than that”. They talk about “being the bigger man”, by walking away from an argument, or responding generously. “It takes a big person”, they say, to have a generous spirit in the face of provocation. We might also include phrases such as “You should be above this” or “It’s beneath you to respond to something like that”.

We perhaps speak more literally today, as is often the case, when we use the antonym, the opposite of magnanimity, and refer to someone who is easily provoked as being petty or small-minded. We may even say “he’s a vicious little man”, referring pointedly, not to someone’s stature, but his character.

I believe that we could benefit from reclaiming the original meaning of magnanimity, by linking it to phrases such as these. To be magnanimous means to be the bigger man, and to be above all petty-mindedness. Why should we care? Isn’t this just semantics? I think it’s psychologically quite important. By restoring this forgotten virtue, and labelling it, we can invoke it in the face of anger. The shift to a values-orientation is inherently antagonistic to the psychology of anger. When we become angry we tend dramatically to shift our focus outward onto the other person. We forget about our own thoughts and actions in the present moment and become mindless rather than mindful, preoccupied with what we want to happen next, such as punishing the target of our anger.

When we focus on virtues, we shift our attention back on to our own character and actions. We recover our mindfulness and self-awareness. We compensate for the impairment of our ability to weigh up the long-term cost of our actions against the perceived benefits of our anger by falling back on our principles for guidance. Ask yourself, for instance, in the heat of the moment: “Will I regret this later when I’m no longer angry?” Ask yourself, “Is getting angry in accord with my core values? Is this the sort of person that I want to be in life?” Ask yourself, “What sort of person am I right now: magnanimous or the opposite? Am I ‘bigger than this’, or am I being petty and small-minded?”

You need a quick and simple solution to anger in the heat of the moment, when you’re not thinking straight, and under pressure. Appealing to your values is quicker and easier, it uses less mental bandwidth (“cognitive load”) than trying to carry out a detailed cost-benefit analysis of your actions. Once you’ve regained your self-awareness, ask yourself, “What would I do if acting in accord with my true values? Instead of yelling or acting aggressively, what would be the magnanimous response right now?” What would the bigger person say or do right now?

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stoic MagnanimityHere is a selection of passages from different ancient philosophers, which help to shed some light on the importance they placed on magnanimity. In earlier authors, magnanimity is associated, as today, with generosity. For the Stoics, however, and some other philosophers, such as Cicero, the emphasis shifts and becomes more associated with a form of emotional resilience.

For example, we’re told that the early Greek Stoics classed magnanimity as one of the most important virtue because is specifically entails “rising above” external events.

Magnanimity they define as the knowledge or habit that makes one superior to [literally “above”] whatever happens, whether good or evil. — Diogenes Laertius, 7.1.93

We’re therefore told that the Stoic philosopher Hecato of Rhodes, following Zeno and Chrysippus, the founders of Stoicism, taught that magnanimity is an integral part of all virtue.

“For if magnanimity by itself,” he says, “can make us superior to everything, though it is only one part of virtue, then virtue too is sufficient for happiness [eudaimonia], in that it looks down on all things that seem troublesome.” — Diogenes Laertius, 7.1.128

In other words, true magnanimity allows us to look down upon all of our troubles. This quality makes virtue self-sufficient, they reason, because, by definition, magnanimity is not dependent upon anything external. The “great souled” individual neither needs praise nor fears criticism, he is completely free from attachment to externals. He realizes that everything he needs to flourish and achieve eudaimonia is within him.

Photo by Art of Hoping on UnsplashMusonius Rufus on Magnanimity

Photo by Art of Hoping on UnsplashMusonius Rufus on MagnanimityI’m going to quote several passages from the Stoic teacher, Musonius Rufus’ lecture on why a philosopher will not sue someone for assault. Musonius focuses on the role magnanimity plays in the Stoic’s response to physical or verbal attacks.

[…] a sensible person would not resort to lawsuits or indictments since he would not think that he had been insulted. Indeed, it is petty to be vexed or put out about such things. He will calmly and quietly bear what has happened, since this is appropriate behavior for a person who wants to be magnanimous. — Musonius Rufus, 10.3

This is a clear example of how magnanimity makes “forgiveness” seem irrelevant to Stoics. The Stoic Sage, or wise person, “would not think that he had been insulted”, in the first place. He is, ideally, so much “bigger than that”, or magnanimous, that he does not consider himself to have significantly injured, and there is therefore nothing to forgive, or any reason to sue his assailant for compensation.

Musonius immediately follows this by citing the famous legend according to which Socrates was in the audience for a performance of Aristophanes’ comedy The Clouds, which mercilessly lampoons the philosopher, and even contributed to his eventual trial and execution.

Socrates obviously refused to be upset when he was publicly ridiculed by Aristophanes; indeed, when Socrates met Aristophanes, he asked if Aristophanes would like to make other such use of him. It is unlikely that this man would have become angry if he had been the target of some minor slight, since he was not upset when he was ridiculed in the theater! — Musonius Rufus, 10.4

The story goes that when Socrates heard some foreigners asking who it was that was being mocked on the stage, he calmly rose from his feet to publicly acknowledge that he was the one being satirized, before sitting back down and enjoying the rest of the play. Here, magnanimity is the quality specifically associated with an ability to shrug off insults without becoming angry.

In the next passage, Musonius gives the example of the Athenian statesman, Phocion the Good.

Phocion the Good, when his wife was insulted by someone, didn’t even consider bringing charges against the insulter. In fact, when that person came to him in fear and asked Phocion to forgive him, saying that he did not know that it was his wife whom he offended, Phocion replied: “My wife has suffered nothing because of you, but perhaps some other woman has. So you don’t need to apologize to me.” — Musonius Rufus, 10.4

Again, this provides a very clear example of how, for the Stoics, neither an apology nor forgiveness is necessary, or meaningful, because the wise man would never take serious offence in the first place. In the absence of any real injury, what sense would it make to expect an apology or offer to forgive anything?

And I could name many other men who were targets of abuse, some verbally attacked and others injured by physical attacks. They appear neither to have defended themselves against their attackers nor to have sought revenge. — Musonius Rufus, 10.4

The magnanimous person has no interest in revenge because there is no real injury to pay back. Given that the Stoics define anger as the desire for revenge, it follows that magnanimity eliminates anger.

Seneca on MagnanimityNext, I’ll quote several passages from Seneca’s On Anger, which explicitly portray magnanimity as the main virtue that opposes the vice of anger. In the opening chapter, Seneca argues that although some people believe that anger can make them great-souled, it actually does the opposite. He goes on to define magnanimity as a form of emotional resilience, incompatible with anger.

I take greatness of mind to mean that it is unshaken, sound throughout, firm and uniform to its very foundation; such as cannot exist in evil dispositions. — Seneca, On Anger, 1.20

In a later chapter, Seneca returns to the topic of magnanimity in relation to anger.

There is no greater proof of magnanimity than that nothing which befalls you should be able to move you to anger. The higher region of the universe, being more excellently ordered and near to the stars, is never gathered into clouds, driven about by storms, or whirled round by cyclones: it is free from all disturbance: the lightnings flash in the region below it. In like manner a lofty mind, always placid and dwelling in a serene atmosphere, restraining within itself all the impulses from which anger springs, is modest, commands respect, and remains calm and collected: none of which qualities will you find in an angry man… — Seneca, On Anger, 3.6

Here, freedom from anger seems to be the very essence of magnanimity. Moreover, the mind of the truly magnanimous man is compared to the celestial realm, the heavens, which lie far above the turmoil of the earth’s weather.

In another passage, again, magnanimity is portrayed as the opposite of anger.

It cannot be doubted that he who regards his tormentor with contempt raises himself above the common herd and looks down upon them from a loftier position: it is the property of true magnanimity not to feel the blows which it may receive. So does a huge wild beast turn slowly and gaze at yelping curs: so does the wave dash in vain against a great cliff. The man who is not angry remains unshaken by injury: he who is angry has been moved by it. He, however, whom I have described as being placed too high for any mischief to reach him, holds as it were the highest good in his arms: he can reply, not only to any man, but to fortune herself: “Do what you will, you are too feeble to disturb my serenity: this is forbidden by reason, to whom I have entrusted the guidance of my life: to become angry would do me more harm than your violence can do me. ‘More harm?’ say you. Yes, certainly: I know how much injury you have done me, but I cannot tell to what excesses anger might not carry me.” — Seneca, On Anger, 3.25

The great-souled man is like an animal so huge, that he can look down upon the hostility of other creatures as if it were simply nothing to him. Incidentally, you may recognize the metaphor of the immovable cliff against which the waves harmlessly crash, which is best-known from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius.

In yet another passage, magnanimity is portrayed as the attitude of someone who views the concerns that people tend to squabble over as being ultimately quite childish and trivial.

“In what way,” say you, “do you bid us look at those things by which we think ourselves injured, that we may see how paltry, pitiful, and childish they are?” Of all things I would charge you to take to yourself a magnanimous spirit, and behold how low and sordid all these matters are about which we squabble and run to and fro till we are out of breath; to anyone who entertains any lofty and magnificent ideas, they are not worthy of a thought. — Seneca, On Anger, 3.32

As I’ve quoted so much from Seneca’s On Anger, I may as well include the closing words of the book, which concludes with one more reference to magnanimity.

Let us keep our tempers in spite of losses, wrongs, abuse or sarcasm, and let us endure with magnanimity our short-lived troubles: while we are considering what is due to ourselves, as the saying is, and worrying ourselves, death will be upon us. — Seneca, On Anger, 3.43

In another of his writings, Seneca names magnanimity the “noblest of all the virtues”.

Besides this, as most insults proceed from those who are haughty and arrogant and bear their prosperity ill, he has something wherewith to repel this haughty passion, namely, that noblest of all the virtues, magnanimity, which passes over everything of that kind as like unreal apparitions in dreams and visions of the night, which have nothing in them substantial or true. — On the Firmness of the Wise Person, 11

In On Clemency, Seneca says that although some virtues are more relevant to some men than to others, magnanimity is important for everyone, because it provides us with emotional resilience.

ConclusionMagnanimity befits all mortal men, even the humblest of all; for what can be greater or braver than to resist ill fortune? — Seneca, On Clemency, 5

My advice is as follows. When you are not angry, ask yourself what it means to you personally to have magnanimity or to be “bigger than” insults, and capable of rising above both good and bad fortune. If you are interested in ancient philosophy, reread the passages above, and consider their meaning very deeply. Contemplate exemplars of magnanimity, perhaps including the famous Stoic philosophers, and other historical or even fictional characters. Look for evidence of this virtue in other people, whom you have known personally. Who exemplifies this virtue for you?

Next, imagine yourself behaving with magnanimity in response to different situations. First, relive memories of events where you became irritated or angry, and imagine yourself responding with magnanimity instead. Second, imagine events in the near future, which might provoke your anger, and rehearse acting with magnanimity instead. Focus on the intrinsic value that you place upon this virtue — imagine that’s the sort of person that you want to be in life.

Finally, in real situations, call upon this virtue and consult it for guidance. If possible, do so before, during, and after problems. Look out for challenging or “high-risk” situations, where your anger may be provoked, and prepare in advance, just beforehand, by saying to yourself, three or four times, “I’m committed to doing this with magnanimity” or “being the bigger person.” In the situation, as soon as you spot the early-warning signs of anger, nip it in the bud, if possible, by asking yourself “How does this anger accord with the value I place on magnanimity?” Once you’ve regained some composure, ask yourself “What would I do if I was acting with magnanimity?”, or a similar sort of question, to guide your actions. Later, when everything is over, and you’re calm and relaxed, review what happened, and ask yourself, “How much magnanimity did I exhibit in that situation? What would I have done differently, if acting with greater magnanimity?” Or, if you prefer, substitute another word or phrase, or just ask yourself how your actions align with your core values in general.

Even if you don’t do all of those things, I hope the general outline gives you some inspiration. You can consult your values in many different ways in relation to challenging situations. Keeping them at the forefront of your mind can be very helpful. It often helps to be more specific, though, about the virtue that you’re working on so I hope that this discussion of the “forgotten virtue” of magnanimity gives you some inspiration in that regard. You’ll find many other references to this concept in the Stoic literature, including, of course, the contemplative practice known today as the View from Above. Try to make it more personal, though, by reflecting on what these ideas mean to you, and how they might be relevant to your character, and the challenges you face in your own life.

Please comment below with your thoughts on how this concept might be applied to different situations and any questions that you might have about how it relates to ancient philosophy or modern psychology.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 14, 2025

Why should you think like a Roman Emperor?

I was recently interviewed about Stoicism by veteran Canadian broadcast journalist Mary Ito for the CRAM podcast. You can watch the video of our conversation on YouTube. The audio is also available on Apple, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. Follow @CRAMideas on Instagram and check out their website.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 12, 2025

The Charmstone of Clan Donnachaidh

My clan has a magic stone. It’s called the Clach na Bratach in Scots gaelic, meaning the Stone of the Standard. It was allegedly discovered in 1314 by Duncan the Stout (Donnchadh Reamhar), the founding chief of the Robertson Clan (Clan Donnachaidh). In this article, I begin by telling you its story, before explaining why I don’t believe in magic but, in a paradoxical sense, I do still believe in magic stones.

Late 19th century woodcut of the Clach na Bratach.

Late 19th century woodcut of the Clach na Bratach.First, let’s discuss how the stone was discovered. The clan warriors were en route to Bannockburn, to fight under Robert the Bruce, when they made camp for the night, and struck their battle standard into the ground beside a nearby fountain. The following morning, as the standard was being pulled up, a clod of earth was dislodged, exposing a mysterious object that was spotted glinting among the dirt and gravel. The chief, mesmerized by this curious artefact, announced that it was a good omen, predicting victory and, sure enough, they were victorious in battle.

Recent photograph of the stone from the Clan Donnachaidh Museum.

Recent photograph of the stone from the Clan Donnachaidh Museum.Seven centuries after its legendary discovery, the stone is now exhibited in the Clan Donnachaidh Museum in Pitlochry. It is a polished crystal ball, about the size of an apple. The clan’s warriors reputedly carried it into battle in a small metal cage atop their standard. In addition to bringing luck, and foretelling the outcome of battles, the Clan Donnachaidh subsequently claimed the stone had healing properties. It became the most celebrated charmstone or “Curing Stone’ in the history of Scotland.

We’re told that it cured all manner of diseases in cattle and horses, and up to a point, also in humans. They would drink the water in which the stone had been “thrice dipped” by the hands of the clan chief. Eventually, in 1715, a crack appeared in the stone just before Chief Alexander Robertson joined the doomed Jacobite rising. The chief was exiled, and the clan’s estates were forfeited, confirming the bad omen.

The stone was, nevertheless, still in use in the late 18th century, according to the text of a Memorandum by Duncan Robertson of Strowan.

There is a kind of stone in the family of Strowan which has been carry'd in their pockets by all their representatives time out of mind. […] They ascribe to this Stone the Virtue of curing Diseases in Men and Beasts, especially Diseases whose causes and symptoms are not easily discover'd; and many of the present Generation in Perthshire would think it very strange to hear the thing disputed.

The author is uncertain whether he believes in its healing powers or not:

The Wits and Philosophers laugh at the notion of ascribing such Virtues to a Stone, as a thing impossible and ridiculous. I wou'd not positively affirm that it has such Virtues as are ascribed to it, but I think I may safely say there is nothing impossible in it.

He explains that “hundreds in former ages, and many alive at this day, affirm that this Stone has been the means of curing some Diseases”. By the end of the 18th century, its perceived benefits were probably linked by many to the Christian faith.

There is a Prayer to be used at dipping the stone; and such Prayers if used with a Heart full of faith and Confidence in the Divine Goodness, wou'd undoubtedly prevail in every Distress, especially where ordinary means are wanting […]

This, of course, leads to an obvious question. After praying over this stone and drinking the water in which it had been dipped, did hundreds of my ancestors in the Clan Donnachaidh, over the centuries, recover from various “diseases whose causes are not easily discovered”, because of the power of suggestion?

The Abbot of Inchaffray blesses the Scots before the Battle of Bannockburn

The Abbot of Inchaffray blesses the Scots before the Battle of BannockburnStoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

My Philosophy of CharmstonesI carry around a magic stone. Sometimes it sits on my desk when I’m working. Sometimes I handle it while walking and thinking about what it symbolizes. I walked into my local witchcraft shop recently and asked the friendly assistant for a stone that symbolizes anger. She recommended a piece of red jasper. I asked my wife to pick the best one out of the basket for me. I do not believe that stones have magic properties. Nevertheless, whenever I look at this one, I recall that it was specifically chosen because of its connection with anger. Whether that association exists in any natural or supernatural sense doesn’t matter to me, because it’s forever the memory that I have established about how it came into my possession. I purposefully created the association in my own mind.

My own personal charmstone.

My own personal charmstone.I’m fascinated by the Clach na Bratach. Not because I actually believe it has magical powers but because I know that, for over five centuries, many hundreds of my clansfolk believed that it did, and that it cured their illnesses. (I’m not so sure how it could have cured their cows and horses, but that’s another matter.) When I look at it, it reminds me of the tremendous potential of the human mind, and I find that quite inspiring.

…we know enough about the power of suggestion to expect that roughly a third to half of them likely exhibited some symptom improvement as a result.

Perhaps not all of the sick people who came to the stone for help were actually cured of their diseases, although I’m confident that for a time, at least, they probably felt as if they were getting better. Moreover, we know enough about the power of suggestion to expect that roughly a third to half of them likely exhibited some symptom improvement as a result. That’s what we find, on average, from countless randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which include placebo control groups. So I believe that there are probably psychological benefits that can be obtained by treating charmstones as a form of autosuggestion. Nevertheless, it may surprise you to learn that’s not the main reason why I use them.

One of the most important psychological mechanisms in modern evidence-based psychotherapy is known as “cognitive distancing” or “cognitive defusion”. We have to use jargon to refer to it because although in some ways it’s a simple concept, it’s also an unfamiliar one to the majority of people, and so no word existed for it in the English language. Cognitive distancing was described by Aaron T. Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy, in his seminal treatment manual, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (1976). Suppose, Beck would say, that you have been wearing coloured spectacles, red ones, for so long that you’ve forgotten about them and now assume that the world is, in fact, reddish. The colour of the lenses becomes totally fused with your perception of external objects.