Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 13

October 23, 2024

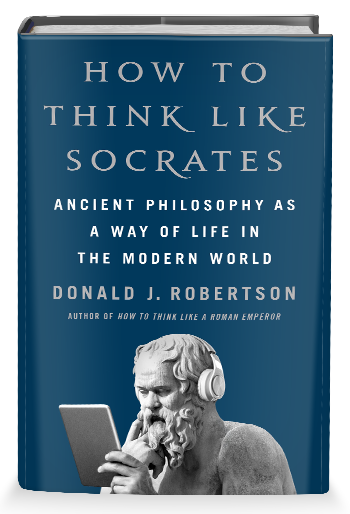

Requesting a Review Copy of "How to Think Like Socrates"

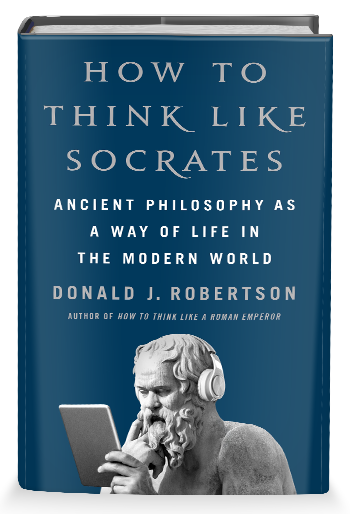

My latest book, How to Think Like Socrates, the follow-up to How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, will be published soon, and is now available for preorder in hardback, ebook, and audiobook formats. (I narrated the audiobook myself.) NB: Don’t forget to fill out the online claim form if you preordered a copy, in order to get access to your bonus rewards.

GiveawayThe Goodreads Giveaway ends in about one day’s time so this is your last chance to enter if you want a chance to win a free copy of the book. (US and Canada only — ends Oct 24th.)

Review CopiesIf you’re a blogger, YouTuber, or podcaster, you can request an advance reader copy (ARC) of How to Think Like Socrates to review, using the online form below. You can also use the form to request an interview with me about the book.

Bulk Orders & Signed CopiesWe’ve made a special arrangement with Porchlight Books, who are taking preorders for signed copies of How to Think Like Socrates. Porchlight are also offering substantial discounts, of up to 37%, for bulk orders of the book. They can also ship books internationally.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Video: Socrates, Stoicism, and Coaching

A deep dive into "How to Think Like Socrates" with Michael Balchan at Heroic coaching. I had to jump straight in a cab to the airport following this session and I’m now in Texas, getting ready to speak with Ryan Holiday about Socrates — stay tuned for the video.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 22, 2024

Socrates versus Roger Stone

This is an article about Greek philosophy and contemporary US politics. Occasionally, I’ve tried to look closely at the views expressed by certain political figures in order to compare them with the ethical teachings of ancient philosophy. They don’t necessarily have to be people with whose politics I agree. I don’t hold opinions about politics strongly wherever there’s room for uncertainty and debate, although I do hold some moral values that have political implications. Stoicism has taught me to remain emotionally detached from questions about which external states-of-affairs are preferable to which.

Once, it’s said, Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school heard a pretentious young man exclaim that he disagreed with everything the (long-deceased) philosopher Antisthenes had written. It’s easy to make yourself seem clever by dismissing something out of hand or doing a hatchet-job on the author. However, Zeno asked him what there was of value to be learned from reading Antisthenes. The young man, caught off guard, said “I don’t know.” Zeno asked him why he wasn’t ashamed to be picking holes in a philosopher’s writings without having first taken care to identify what might be good in his works and worth knowing. That’s not unlike what philosophers call the Principle of Charity today. We arguably gain more benefit from reading a book if we look for the good bits first. Otherwise, if we indulge in criticism straight away, we risk missing what’s most important entirely. So it was with that in mind that I decided to read Stone’s Rules, the latest book from political strategist, and ardent Trump-loyalist, Roger Stone.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Get me Roger Stone!Stone’s story is now permanently entwined with that of Trump. Stone claims he started calling on Trump to put himself forward as a presidential candidate back in 1988, although Trump wasn’t interested at first. “I launched the idea of Donald J. Trump for President”, he says. However, he later qualifies this by saying,

Those who claim I elected Trump are wrong. Trump elected Trump — he’s persistent, driven to succeed, clever, stubborn, and deeply patriotic. I am, however, among a handful who saw his potential for national leadership and the presidency.

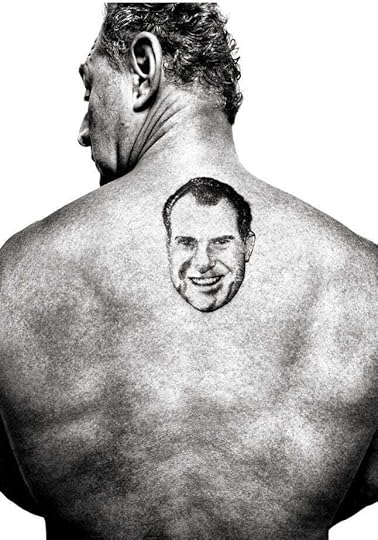

Stone is a specialist in negative campaigning. His political career began way back in 1972 when, aged twenty, he joined Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign team. Nixon became his lifelong hero. Indeed, Stone collects Nixon memorabilia and actually has a large tattoo of the former president’s face on his back. However, after the Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation, Stone was left with a reputation as a professional “dirty trickster”. He successfully turned this into a selling-point and survived to have a long, albeit controversial, career in politics. In the 1980s he worked on Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign and formed the political consulting firm Black, Manafort and Stone, along with Charlie Black and Paul Manafort.

Black, Manafort and Stone’s first client was, in fact, Donald Trump. Later, in the 1990s, Stone began working with Trump in a variety of other capacities. In 2000, he was appointed campaign manager for Trump’s first, albeit abortive, presidential campaign. Trump sought the nomination for the Reform Party but quit during the presidential primaries. It wasn’t surprising then that Stone later served as an advisor to Trump during the initial stages of his 2016 presidential campaign. He resigned in August 2015, although Trump said that he had been fired. However, Stone continued to support Trump and according to some reports to serve in an informal capacity as one of his political advisors. Stone and several of his associates came under the scrutiny of the Mueller investigation, mainly due to Stone’s communications with Julian Assange of Wikileaks and a team of hackers using the online identity Guccifer 2.0, who were subsequently revealed to be acting as agents of Russian military intelligence (GRU).

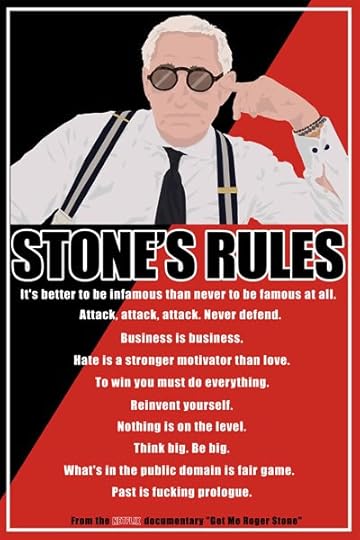

Stone’s a difficult man to describe. He revels in controversy. For example, he posed for a photo shoot dressed as the Joker from Batman. I find that, paradoxically, people who aren’t very familiar with him often assume that others are “attacking” him when in fact they’re just repeating his own claims. He became more widely-known outside of political circles in the summer of 2017 when the Netflix documentary Get me Roger Stone was released. The film is structured around ten of Stone’s “rules” for success in life and politics.

This idea was then expanded into his new book Stone’s Rules: How to Win at Politics, Business, and Style (2018). The blurb compares Stone to a combination of Machiavelli and Sun Tzu. However, the book actually consists of 140 rules, described in a few paragraphs each, written in a fairly casual and often humorous style. There are many short anecdotes about Nixon and other US politicians. As the title suggests, some of the rules are more about succeeding in life, some are more specific to politics. A considerable number of them are about sartorial advice, such as Rule #18: “White shirt + tan face = confidence” or Rule #36, which claims “Brown is the color of shit”. He also includes his mother’s recipe for pasta sauce (or rather “Sunday Gravy”). There are instructions on how to prepare martinis just like Nixon did — who, according to Stone, used to say of them, “More than one of these and you want to beat your wife.”

In the book’s foreword, political commentator Tucker Carlson (formerly of Fox News) acclaims Stone “the premier troublemaker of our time” and “the Michael Jordan of electoral mischief”. However, Carlson also describes his friend as “wise” and “on the level”. Stone is happy to celebrate his notoriety as the “high priest of political mischief”, “slash-and-burn Republican black bag election tamperer” with “a long history of bare-knuckle politics” and the title “Jedi Master of the negative campaign”.

Why Socrates?Stone himself believes that “To understand the future, you must study the past” (Rule #4: “Past is fucking prologue”) and that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. So I want to approach his rules for life from the perspective of ancient Greek philosophy, which began addressing similar ideas almost two and a half thousand years ago, in the time of Socrates. Some of the underlying assumptions about the best way to live, or to govern, haven’t changed much. Stone’s Rule #69 likewise acknowledges that “everything is recycled” in the political arena:

All the ideas today’s politicians present to the voters are simply recycled versions of the same basic formulae that have been employed by political hucksters and power-accumulating government careerists for nearly a century.

Indeed, the arguments Socrates and the Stoics deployed against ancient Sophists address difference of value so fundamental that they’re still just as relevant today. Stone’s rules contain several echoes themselves of perennial philosophical debates about the best way to approach life. Sometimes he says things that resemble Socrates or the Stoics and sometimes he sounds more like their opponents the Sophists. So let’s have a look at a few key examples…

Make Your Own LuckStone’s Rule #5 quite simply advises “make your own luck”. This is a sound piece of age-old wisdom. Socrates likewise argues, in the Euthydemus, that wisdom is man’s greatest gift because it allows him to turn bad fortune into good. In Plato’s Republic, Book Ten, Socrates also says that unlike the majority of people the true philosopher isn’t perturbed by apparent setbacks. He realizes that we can never be certain whether the events that befall us will turn out to be good or bad in the long-run — there are many reversals of fortune in life. If we stop to complain about every apparent setback, we do ourselves more harm than good. In these passages, Socrates sounds very much like a forerunner of the Stoics. For example, Epictetus, the most famous Roman Stoic teacher would later say that wisdom, like the magic wand of Hermes, has the power to turn everything it touches into gold — he means that the wise man knows how to turn apparent misfortune to his advantage.

Stone’s Rule #60 is his version of the wand of Hermes: “Sometimes you’ve got to turn chicken shit into chicken salad.”

In politics and in life, you play the cards you are dealt. Sometimes you have to take your greatest disadvantage and turn it into a plus. Lyndon Johnson called it “changing chicken shit into chicken salad.”

According to Stone, Donald Trump particularly exemplifies this philosophy of life. Likewise, Rule #13 “Never quit” cites Donald Trump, Winston Churchill and Richard Nixon as exemplars of psychological resilience and persistence in the face of setbacks. Stone quotes Nixon as saying “A man is not finished when he is defeated, he is only finished when he quits.”

Stone also admires G. Gordon Liddy who lived by Nietzsche’s maxim “That which does not kill me can only make me stronger.” Liddy might appear a surprising choice of role model. He was the man who, under orders from Nixon, led the Watergate burglary of the DNC headquarters, and was sentenced to twenty years in prison for doing so. Stone’s right to say, though, that in many cases “Today’s defeat can plant the seeds of tomorrow’s victory.” For example, as a psychotherapist and counsellor, I often heard clients tell me that, paradoxically, losing their job turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to them. Psychological endurance isn’t a virtue in itself, though, as Socrates points out in the Laches and elsewhere. It really only deserves praise when it’s in the service of something good rather than evil. Crooks can be very resilient. Toughness in the service of vice is arguably just another form of weakness.

Hate Trumps LoveRule #54 “Hate is a stronger motivator than love” appears to be one of the fundamental premises of Stone’s entire political philosophy. It’s the basis of his favourite strategy: negative campaigning. Hatred is, he thinks, the most powerful motive incentivizing voters in US elections:

Only a candy-ass would think otherwise. People feel satisfied when there is something they can vote FOR. They feel exhilarated when there is something — or someone — they can vote AGAINST. Just ask President Hillary Clinton about all of the people who rushed out to vote FOR her.

Stone argues that Trump’s central campaign theme was extremely positive “Make America Great Again” but that he was nevertheless “the beneficiary, and an extraordinarily deft amplifier, of a deep, and frankly much-deserved, loathing” for Hillary Clinton.

Do-gooders and disingenuous leftists who decry the politics of fear and negativism are simply denying the reality of human nature, and only fooling themselves. Emotions cannot simply be erased or ignored, and to believe they can is a suicidally-naive approach to political competition.

There’s undoubtedly some truth in this but is it the whole truth? Stone’s Rule #52 “Don’t get mad; get even” arguably hints at a contradictory observation about human nature:

Be aggressive but don’t get angry. Nixon would get angry and issue illegal orders then reverse them when he calmed down.

So why isn’t the same true of voters? Hatred and anger are certainly powerful motivators but so are fear and regret. When people act out of hatred they’re not usually thinking rationally about the wider implications or long-term consequences of their actions: it’s more of a knee-jerk response. That often leads to a pendulum swing when the negative consequences of decisions motivated by anger become apparent. Perhaps, just like Nixon, voters might act out of anger (as a result of negative campaigning) but then come to regret their decision once they’ve calmed down again.

The danger of negative campaigning is that in voting against someone they have been encouraged to hate voters end up electing someone else, not on the basis of merit or competence, but just because they symbolize opposition to the hate figure. That can backfire dramatically, though, if it turns out the winning candidate’s shortcomings have been overlooked. Indeed, as we’re about to see, Stone is quite candid about employing his trademark negative campaigning strategy to create a smokescreen and divert attention away from potentially damaging criticism of his allies.

The Big LieStone’s Rule #47 “The Big Lie Technique”.

Erroneously attributed to Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels, the “big lie” manipulation technique was actually first described in detail by Adolf Hitler himself. […] Nonetheless, the tactic of creating a lie so bold, massive, and even so monstrous that it takes on a life of its own, is alive and well all through American politics and news media. Make it big, keep it simple, repeat it enough times, and people will believe it.

Arguably, a classic example of this would be the “birtherist” conspiracy theory, which falsely claimed that Barack Obama was born in Kenya in order to cast doubt on his eligibility to serve as US president. Stone previously stated in an interview that although he didn’t plant the idea of birtherism in Donald Trump’s mind he did encourage him to keep spreading it. However, although Stone proudly advocates this technique it obviously doesn’t serve his interests to place examples of his own handiwork under the spotlight so he doesn’t actually mention birtherism anywhere in his book.

Instead, he focuses on the claim that the Democrats propounded a “Big Lie” by claiming that the Russian state helped Donald Trump win the 2016 presidential election and that Stone himself had played a role by colluding with Wikileaks. So despite writing about his mastery of this art in this book he’s also claiming that his enemies are the ones really perpetrating it. Of course, you can’t credibly admit that you’re telling Big Lies and then, in the next breath, go on to accuse your opponents of doing so unless you back that up with some pretty compelling evidence. Stone’s assumption, though, is that enough people won’t notice or don’t care about that. In some respects, he may be right.

One of the main reasons Stone gives for using the Big Lie is to create a smokescreen to defend yourself against criticism. Stone’s Rule #41 “Attack, attack, attack — never defend” and #42 “Let no attack go unanswered” hammer home the point that the best form of defence is attack. Stone’s argument is that, in life generally but especially in politics, if you try to defend yourself against criticisms rationally you simply risk educating more people about the accusations against you. Mud sticks. So instead launch a “devastating” counter-attack to divert attention away from the charges against you, and ignore them or at least say as little as possible in rebuttal of them. It doesn’t matter, of course, whether the criticisms you face are actually valid or not. Hence, Stone’s Rule #81 “Never Admit Mistakes”. He mentions briefly in passing that people will probably say that’s what he’s doing in response to the allegations that he colluded with Russia during the 2016 election campaign but he denies this and focuses instead on claiming that it’s all part of a Democrat / Deep State conspiracy against him.

In a nutshell, Stone believes that if someone attacks you in politics you should focus on attacking their character even more aggressively than they’ve attacked yours, and avoid having to defend yourself rationally. This is what philosophers call the ad hominem fallacy, being deployed as a deliberate rhetorical strategy. It’s also similar to the fallacy of “Whataboutism” or changing the subject — Never mind Russian collusion what about Hillary’s email server?! The hope is that everyone will forget about the criticisms made against you and focus on the allegations, true or false, that you’re making against your opponents. If it works, you’ve thrown them off your trail completely and instead sent them down an endless rabbit hole of conspiracy theories. Of course, that doesn’t prove you’re innocent, it just diverts attention away from the problem by changing the subject. Try that one in court: “Never mind that I robbed a bank what about the judge — everyone knows he’s a Communist and I heard he’s also the head of a weird sex cult!”

However, as Jon Meacham says “Lies are good starters but they’re not good finishers.” The truth usually comes out eventually. Stone is probably right that, rhetorically, it’s a very powerful strategy to attack the character of your critics instead of answering their criticism. However, that won’t keep working forever. Sooner or later your credibility will begin to wane as a result and people will stop taking you seriously, just like the proverbial boy who cried wolf. It might take months, or it might take years, even decades, but the more “Big Lies” you tell the more people will eventually begin to question your credibility.

Worse, although the Big Lie strategy may work quite well in the political arena, at least in the short-term, it has the potential to come back to haunt you in the law courts. For instance, some reports suggest that Stone is likely facing indictment as part of the Russia investigation. What would happen if the prosecution chose to read certain passages from this book aloud before a judge and jury? Once you admit to using deceit on a massive scale to deflect criticism, and never admitting to wrongdoing as a matter of principle, how can anyone ever again trust anything you try to say in your own defense? What goes around comes around.

Book One of Plato’s Republic features a Sophist called Thrasymachus (literally “fierce fighter”). Stone sometimes sounds a bit like him. Thrasymachus adopts the cynical position that justice is for losers and that true wisdom is possessed by those courageous enough to become unjust, by lying, cheating, and getting away with it. He particularly admires tyrants, who hold absolute political power and can do what they want. He looks down on the sheep who bleat about morality as naive simpletons. Might is right, in other words. The honest and just man, he thinks, is bound to be exploited by the dishonest and unjust. Socrates claims that the unjust seek power because they want to gain from it. However, truly good men do not seek political power for its own sake but are more often motivated by the desire not to allow tyrants to rule.

Socrates doesn’t say this explicitly but he strongly implies the view that the motivation of good and honest people to become involved in politics will wax and wane, reaching its peak in response to the threat of tyrants seizing power. History, in other words, may consist of a pendulum swinging between periods of political complacency, when corrupt leaders are allowed to take power, and periods of moral outrage when the people realize they’ve been duped and become motivated to set things right.

Thrasymachus is convinced that the unjust are always stronger than the just. However, Socrates argues that injustice breeds division and hostility, creating enemies within and without the state over time. Justice, by contrast, breeds harmony and friendship, and creates stronger alliances, although we might add that justice often moves more slowly than injustice. So although the unjust may prevail in the short term, over time their power is bound to crumble as they increasingly find their associates turning against them. Their problem is that they can’t really trust anyone.

Hypocrisy is BadStone’s Rule #84 says “Hypocrisy is what gets you”, so he actually does recognize the danger of losing credibility. However, throughout the book he refers countless times to the deliberate use of hypocrisy, insincerity and deceit. For example, Stone’s Rule #55 “Praise ’em before you hit ‘em”:

This technique was one of Dick Nixon’s best. The veteran political pugilist would praise his opponent’s sincerity and commend the opponent’s genuine belief in what are, nonetheless, terrible ideas and repugnant ideologies. […] “Praise ’em before you hit ‘em — makes the hit seem more reasonable and even-handed, and thus more effective,” said the Trickster.

Likewise, Stone’s Rule #39 “Wear your cockade inside your hat” by which he means that it can be advantageous to conceal your true affiliations from everyone except your allies. He writes “sometimes it is best to cloak your real political intentions, so you are able to accomplish more without being under suspicion.” But once you’ve told everyone that, in a book, you’ve kind of let the cat out of the bag haven’t you?

There’s undoubtedly some truth to the idea that deceit can be expedient in politics and Big Lies can have powerful effects. However, these aren’t qualities we normally praise or admire in other people, which makes it hypocritical to adopt them ourselves. That might work in the short-term but, once again, in the longer-term more and more people are likely to figure out what’s going on and you risk losing credibility as a result. If your philosophy is based on deceit you also run the risk of surrounding yourself with fair-weather friends who share similarly ruthless values. So you better hope that when a crisis looms they don’t just decide it’s expedient to throw you under the bus to save their own skin. For instance, that’s typically what happens when defendants agree to plea bargains and turn state’s evidence against their erstwhile “friends” during criminal investigations.

ConclusionStone prefaces his rules by explaining:

To me, it all comes down to WINNING. It comes down to using any and every legal means available to achieve victory for my friends and allies, and to inflict crushing, ignominious defeat on my opponents and, yes, enemies.

I can’t read this without thinking of Conan the Barbarian who, when asked what is best in life, replies: “To crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women!” I doubt Stone would object to the comparison. He describes his book as a “compendium of rules for war” and “the style manual for a ‘master of the universe’”.

So from the outset winning is everything. Although, a couple of pages later in Rule #1 he also says “There is no shame in losing. There is only shame in failing to strive, in never trying at all.” That attitude interests me because it’s more consistent with the values espoused by Socrates and the Stoics. If we invest too much value in outward success then we inevitably place our happiness, to some extent, in the hands of fate. The philosophers thought wisdom and resilience came from avoiding that and learning to place more importance on our own character and less on the outcome of our actions. It’s one thing to aim at a particular outcome, such as winning an election. It’s another thing to make it so all-important that we’re willing to sacrifice our own integrity in pursuit of it. That’s a recipe for neurosis because it makes our emotions depend upon events that are never entirely up to us. Stone’s good off to a good start with Rule #1 and it should make us wonder what would have happened if he’d developed that thought further and incorporated it into a more rounded philosophy of life.

That’s how the book begins. It concludes with Stone’s Rule #140 “He who laughs last laughs heartiest”:

I will often wait years to take my revenge, hiding in the tall grass, my stiletto at the ready, waiting patiently until you think I have forgotten or forgiven a past slight and then, when you least expect it, I will spring from the underbrush and plunge a dagger up under your ribcage. So if you have fucked me, even if it was years ago, don’t think yourself safe.

That brought to my mind something his hero Richard Nixon once said:

“I want to be sure he is a ruthless son of a bitch, that he will do what he’s told, that every income tax return I want to see I see, that he will go after our enemies and not go after our friends.”

Those are the words of Nixon giving instructions to his aides about the appointment of a new commissioner of internal revenue, caught on tape in the Oval Office on May 13, 1971. As part of this attempt to persecute his opponents, Nixon later handed his notorious “Enemies List”, containing 576 names in its revised version, to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). He assumed political power was a weapon to be wielded, a way of harming his enemies and helping his friends.

Nixon’s words happen to echo an ancient Greek definition of justice as “helping your friends and harming your enemies”, which Socrates vigorously attempted to refute nearly two and a half thousand years ago. In Book One of Plato’s Republic, Socrates basically points out that to genuinely harm your enemies, by definition, is to make them worse than they are already. Just making them weaker by removing certain external advantages such as wealth, friends, or status doesn’t necessarily harm them deep down. As Stone himself conceded: the wise man can “make chicken shit into chicken soup” and turn setbacks into opportunities.

We can only really harm others, according to Socrates, by corrupting their character and turning them into foolish and vicious people, if that’s even possible. He concluded that, paradoxically, the wise man will actually help both his friends and his enemies. That doesn’t mean giving his enemies external advantages, which would be foolish because they’d probably use them against us other others. Rather it means educating them and helping them to become wiser and better individuals, perhaps one day becoming our friends instead of our enemies as a result. Of course that’s idealistic, but it’s arguably a much healthier goal than simple revenge.

I’ll cut to the chase and say that I think the future of American politics should perhaps involve greater bipartisanship. People would do better to try to understand their political enemies, in my view, rather than simply attack them. The law of retaliation (lex talionis) is “an eye for an eye” but as Gandhi reputedly said, that leaves the whole world blind. Socrates argues that revenge harms us more than it does our enemies because it degrades our character and tricks us into investing far too much importance in external things. I’ll therefore leave the last word to him:

“Then we ought to neither return wrong for wrong nor do evil to anyone, no matter what he may have done to us. Be careful though, Crito, that by agreeing with this you do not agree to something you do not believe. For I know that there are few who believe this or ever will. Now those who believe it, and those who do not, have no common ground of discussion, but they must necessarily disdain one another because of their opinions. You should therefore consider very carefully whether you agree and share in this opinion. Let us take as the starting point of our discussion the assumption that it is never right to do wrong or to repay wrong with wrong, or when we suffer evil to defend ourselves by doing evil in return.” (Crito, 49c)

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 17, 2024

The Saad Truth about Happiness

In this episode, I speak with Dr. Gad Saad. (Apologies for the room reverb on my mic!) Dr. Saad is a well-known public intellectual, champion of free speech, and renowned evolutionary psychologist. He is Professor of Marketing at the John Molson School of Business, at Concordia University, in Montreal, and has recently also been appointed Visiting Professor and Global Ambassador at Northwood University. Gad has a popular YouTube channel, and a podcast called The Saad Truth, and he’s the author of several best-selling books; the latest one is titled The Saad Truth about Happiness: 8 Secrets for Leading the Good Life. Yesterday was the four-year anniversary of the release of his most widely-known book The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense. Gad is currently working on his next book Suicidal Empathy.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Highlights

HighlightsWhat is happiness? Are some people confused about what it means to be happy?

What makes us so unhappy today?

Do consumerism and celebrity culture make us unhappy? .

The relationship between emotional resilience and happiness

Secrets to living a happy life

What problems are caused by woke culture and political correctness?

For and against anger

LinksThe Saad Truth about Happiness

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 13, 2024

Sharing Your Reviews of "How to Think Like Socrates"

Thanks to everyone who downloaded their advance review copy of my latest book How to Think Like Socrates. NB: If you haven’t already done so, you can still request a review copy if you have a Founder membership — see the link at the end of this post. If you can leave feedback on Netgalley or Goodreads before 19th Nov, the publication date, that would …

October 12, 2024

The Golden Rule in Stoicism

All things therefore whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, even so do ye also unto them. — Matthew, 7.12

Treat others as you would like to be treated by them. The “Golden Rule”, as it’s known, is one of the simplest and most influential of all ethical principles. In this article, we’ll begin by looking at what it is before exploring some examples found in the writings of Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and other Stoic philosophers.

The Golden Rule is a remarkably simple guide to ethical behaviour, which anyone can understand and try to follow. It’s found in both positive and negative forms:

Do what you would praise others for doing

Avoid doing what you would criticize others for doing

Indeed many people today take it for granted that applying a different standard to other’s actions than we do to our own would be a form of moral hypocrisy.

I explored the ways Stoicism can be used as a guide to modern life in my recent book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, but this article will focus on a very simple principle that Stoics used as a guide to ethical action. People often say they find Stoic ethics confusing and want a very clear and simple example of practical advice, well here it is…

Judaism and Christianity

Judaism and ChristianityVersions of the Golden Rule have been identified in many different philosophical and religious traditions, throughout history and across different cultures. For instance the Talmud quotes the Hebrew sage Hillel the Elder as teaching:

What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.

This is one of the the Golden Rule’s most famous expressions, alongside several instances found in the New Testament. For example, in addition to the quote from the Gospel of Matthew at the start of this article, there’s also:

And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise. — Luke, 6.31

However, the Golden Rule is also clearly a theme in Greek and Roman philosophy, especially for the followers of Socrates and later the Stoics. The New Testament actually claims that St. Paul addressed a group of Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, at foot of the Athenian Acropolis, quoting a couple of lines to them from the Stoic philosopher-poet Aratus (Acts, 17.16).

Paul and other early Christians are therefore known to have been familiar with Stoic philosophy. Indeed, Stoicism is believed by many modern scholars to have been one of the key philosophical influences upon early Christian ethics. Whether or not early Christians actually derived the Golden Rule from Stoic philosophy, they must have realized that the Stoics had already been teaching very similar ideas. It’s the ethics of the Socratic and Stoic tradition that we’re going to focus on therefore in the rest of this article.

Socrates and the Golden Rule

Socrates and the Golden RuleAlthough, the Golden Rule is most commonly associated with Christianity, it was arguably also implicit, centuries earlier, in the Socratic Method or elenchus. Socrates taught that we should cross-examine ourselves regarding our moral convictions. The word he uses for his method, elenchus, refers to questioning a witness in court in order to expose contradictions in their testimony. In the Socratic dialogues written by both Plato and Xenophon that sometimes takes the form of Socrates drawing attention to someone applying a double standard morally by praising or criticizing qualities in others but not in themselves. Socrates described his use of “Socratic Questioning” as a sort of therapy that aims to cure people of their conceit regarding the most important things in life, especially contradictory assumptions about the nature of good and evil, virtue and vice. It’s a cure, in other words, for moral hypocrisy and inconsistency.

For instance, in one of Xenophon’s dialogues, Socrates asks a young man called Critobulus to describe the qualities he’s seeking in a friend (Memorabilia, 2.6). They agree that the ideal friend would have positive qualities such as moral virtue, self-discipline, and kindness. However, Socrates suddenly turns the question around by asking Critobulus how many of these qualities he embodies himself. He’s ashamed to admit that he possesses very few of them. He was judging others by a standard, for being a good friend, that he neglected to apply to himself. Socrates makes him realize that because he finds it fairly easy to describe what behaviour he would praise in others that can potentially serve as a reliable guide when it comes to judging his own character and actions.

In another dialogue, Socrates’ friend Chaerecrates is complaining about his older brother’s behaviour. He wants his brother to treat him with more respect but claims he doesn’t know how to achieve this.

‘I assure you,’ said Socrates, ‘so far as I can see, you needn’t employ any subtle or novel method on him: I think you could prevail on him to have a high regard for you by using means which you understand yourself.’ — Xenophon, Memorabilia, 2.3

It’s not rocket science, in other words. Chaerecrates, though, insists he’s not aware of any magic formula for winning other people’s respect.

‘Tell me, then,’ said Socrates, ‘if you wanted to prevail upon one of your acquaintances to invite you to dinner whenever he was holding a celebration, what would you do?’

Chaerecrates admits that, of course, he’d begin by taking the initiative and inviting the other person to dinner first. Socrates therefore asks what he’d do if he wanted someone to take care of his property while he’s travelling. Charecrates says he’d offer to do the same for them first. What, asks Socrates, if you wanted a foreigner to invite you to their home as a guest when visiting their country? Once again, Charecrates admits that “obviously I should first have to do the same for him.” Socrates, with typical irony, concludes:

‘So you know all the magic spells that influence human conduct, and have kept your knowledge dark all this time! Why do you hesitate to begin? Are you afraid that you will look bad if you treat your brother well before he treats you well?

Of course, our moral values need to be sound in the first place but Socrates quite rightly pointed out that much progress can be achieved toward rationality simply by resolving inconsistencies in our ethical thinking.

The only difference here is that Socrates limits this advice to treating our friends as we wish to be treated by them in return. However, in other dialogues he appears to argue that the wise man seeks to help both friends and enemies. Nevertheless, these examples and others clearly show there’s plenty of “Golden Rule” type thinking to be found in the Socratic dialogues. Indeed, in Plato’s Laws, although it’s not attributed to Socrates, the Golden Rule is stated quite explicitly in relation to property rights:

The Golden Rule in StoicismThe principle of them is very simple: Thou shalt not, if thou canst help, touch that which is mine, or remove the least thing which belongs to me without my consent; and may I be of a sound mind, and do to others as I would that they should do to me. — Plato, Laws, 11.913

The Stoics reputedly considered themselves to be a Socratic school of philosophy and they drew a great deal of inspiration from Socrates. In their writings, we therefore find the Golden Rule developed into something much closer to its more familiar form, as found in the Christian tradition.

In the fragments from the Stoic Hierocles preserved by Stobaeus, for instance, we find a very clear expression of the Golden Rule:

The first admonition, therefore, is very clear, easily obtained, and is common to all men. For it is a sane assertion, which every man will consider as evident. And it is this: Act by everyone, in the same manner as if you supposed yourself to be him, and him to be you. — Hierocles, Fragments

Hierocles goes on to illustrate this point by reference to the master-slave relationship:

For he will use a servant well who considers with himself, how he would think it proper to be used by him, if he indeed was the master, and himself the servant. The same thing also must be said of parents with respect to children, and of children with respect to parents; and, in short, of all men with respect to all. — Hierocles, Fragments

In discussing the master-slave relationship, the Stoic philosopher Seneca likewise wrote:

But this is the kernel of my advice: Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your betters. — Seneca, Letters, 47

The same sentiment is expressed elsewhere in more general terms, in a passage where Seneca, without giving the source, presents it as a familiar maxim he’s quoting:

“You must expect to be treated by others as you yourself have treated them.” We receive a sort of shock when we hear such sayings; no one ever thinks of doubting them or of asking “Why?”— Letters, 94

In On Anger, Seneca explains that when growing angry with another person over some perceived transgression, Stoics should remind themselves that they are capable of doing the same or similar things.

No one says to himself, “I myself have done or might have done this very thing which I am angry with another for doing.” — Seneca, On Anger, 3.12

A few sentences later, he expands upon this by also applying a version of the Golden Rule to the problem of anger:

Let us put ourselves in the place of him with whom we are angry: at present an overweening conceit of our own importance makes us prone to anger, and we are quite willing to do to others what we cannot endure should be done to ourselves.— Seneca, On Anger, 3.12

Elsewhere, Seneca applies this wisdom to the question of how best to bestow gifts or favours on others:

Let us consider… in what way a benefit should be bestowed. I think that I can point out the shortest way to this; let us give in the way in which we ourselves should like to receive. — Seneca, On Benefits, 2.1

In one of the fragments sometimes attributed to Epictetus, he writes:

What you avoid suffering yourself, seek not to impose on others. — Epictetus, Fragments

Epictetus, himself a freed slave, continues as follows:

You avoid slavery, for instance; take care not to enslave. For if you can bear to

exact slavery from others, you appear to have been yourself a slave. For vice has nothing in common with virtue, nor freedom with slavery. As a person in health would not wish to be attended by the sick nor to have those who live with him in a state of sickness ; so neither would a person who is free bear to be served by slaves, nor to have those who live with him in a state of slavery. — Epictetus, Fragments

Marcus Aurelius nowhere states the Golden Rule as explicitly as either Hierocles or Seneca. The closest he comes is in the following passage:

See that you never feel towards misanthropes as such people feel towards the human race. — Meditations, 7.65

However, throughout The Meditations he does adopt the related assumption that we should treat all others as our “kinsmen” and fellow citizens. For instance, in perhaps one of the book’s most famous passages he writes:

Nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, for we are made for co-operation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away. — Meditations, 2.1

Marcus elsewhere says that someone who is wise remembers “that every rational being is his kinsman, and that to care for all men is according to man’s nature” (Meditations, 3.4).

Regarding the actions of others he writes:

This is from one of the same stock, and a kinsman and partner, one who knows not however what is according to his nature. But I know; for this reason I behave towards him according to the natural law of fellowship with benevolence and justice. — Meditations, 3.11

In one of the most striking passages in The Meditations, he appears to echo the Christian notion of loving even one’s enemies:

It is peculiar to man to love even those who do wrong. And this happens, if when they do wrong it occurs to thee that they are kinsmen, and that they do wrong through ignorance and unintentionally... — Meditations, 7.22

Finally:

ConclusionA branch cut off from the adjacent branch must of necessity be cut off from the whole tree also. So too a man when he is separated from another man has fallen off from the whole social community. Now as to a branch, another cuts it off; but a man by his own act separates himself from his neighbor when he hates him and turns away from him, and he does not know that he has at the same time cut himself off from the whole social system. Yet he has this privilege certainly from Zeus, who framed society, for it is in our power to grow again to that which is near to us, and again to become a part which helps to make up the whole. — Meditations, 11.8

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. For Socrates treating friends otherwise was a moral contradiction, a double standard, and therefore irrational. He even implies that we should show our enemies with the same regard. A few generations later, the Stoics took his ethical philosophy and developed it into more of a system. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, had said, like Aristotle before him, that a friend is “another me” (alter ego est amicus). However, we are to strive to make all men (and women) our friends. The Golden Rule gradually become more explicit and took on its familiar form in authors such as Seneca when he admonishes us for being “quite willing to do to others what we cannot endure should be done to ourselves”.

Finally, in Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquity, we find a systematic emphasis on the ethics of brotherly love, which the Stoics called philostorgia or “natural affection”. We’re to regard ourselves and others as brothers and sisters, even as limbs of the same organism. From this vision of the unity of humankind, it follows naturally that we should apply the same moral standard to others that we apply to ourselves. This is probably one aspect of what the Stoics meant when they described the supreme goal of life according to their philosophy as living consistently.

October 11, 2024

Discussion: How has Stoicism improved your life?

What are the most important ways in which you feel Stoic philosophy has had an impact on your life? How does it change things for you? Which ideas or practices do you find most useful? Share your thoughts below and read about what other people have found most helpful. (Please respond, if you can, to at least one other comment in the thread, to help the conversation grow.) Let’s see what people have to say!

Photo by Cliff Johnson on Unsplash

Photo by Cliff Johnson on Unsplash

October 10, 2024

Rewards for Preordering How to Think Like Socrates

Preorder my latest book How to Think Like Socrates today and you'll be eligible to claim exclusive bonus content. (If you’re interested in getting a signed copy, you can preorder one from Porchlight — they will ship internationally.)

Join me for an exclusive live Q&A on Zoom where we'll dive deeper into the book. Tues 19th Nov at 6-7pm Eastern Time. NB: A recording will be available for playback if you're not able to attend.

Download a free, actionable cheat sheet to help you apply Socratic wisdom from the book to your daily life.

Enjoy 6 months of full access to my Substack newsletter, packed with insights and exclusive content.

Gain access to bonus audio and video interviews, offering unique perspectives on the book.

Follow these stepsPreorder the book.

Log into the claim form using a Google account, and complete it.

Wait to receive an email after 20th Nov, with links for your rewards.

NB: You will need a Google account to access the claim form. Dates are based on the US release; you may find the book is published on another date in different countries. If you've already preordered your copy, before reading this, feel free to go ahead and submit your claim form now.

Terms and conditions. All orders placed before Nov 19th are eligible. You must submit your details using the online claim form on this page. The bonus content will be sent to you using the email you provide. If you are already a paying subscriber to my Substack newsletter, you will receive a complimentary six month extension. Details of this offer may be subject to change without prior notification.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 5, 2024

Could the Meaning of Life be Lorem Ipsum?

What if you discovered that the meaning of life was somehow hidden right under your nose?

Suppose the most important idea in the entire universe was written down in plain sight, but overlooked by everyone. That the words, assumed to be nothing but incomprehensible garbage, were being used as a filler — placeholder text for graphic design? That would be pretty ironic, wouldn’t it?

Lorem ipsum is the name given to the (mangled) Latin text commonly used in publishing as a generic placeholder, since around the 1960s. It allows designers to arrange the visual elements of a page of text, such as font and layout, without being distracted by the content. Other Latinate words are occasionally used because it’s assumed just to be garbage. Here is a typical example, though, of some lorem ipsum placeholder text.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Here’s the thing: the Lorem ipsum text isn’t actually meaningless. The Latin was so corrupt that the original source was almost unrecognisable. Nevertheless, in the early 1980s, a Latin scholar called Richard McClintock, based in Virginia, accidentally discovered the source of the passage in a well-known philosophical text. It’s derived from a book called De Finibus, which was written in the first century BC, by the famous Roman statesman and philosopher, Cicero. He was a follower of the philosophy taught by Plato’s successors in what’s known as the “Academic” school.

The Meaning of LifeAlthough it’s usually just referred to as De Finibus, the full Latin title is De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, which is notoriously tricky to translate into English. Literally, it means “On the ends of good and evil”, but really it concerns different philosophical views about the best way of life, which comes fairly close to what we would refer to today as the “meaning of life”.

De Finibus is a series of five dialogues in which Cicero portrays himself and his friends discussing the major schools of Roman philosophy. After weighing the pros and cons of Epicureanism and Stoicism, Cicero concludes with an account of the “Middle Platonism” introduced to the Academy by his own teacher, Antiochus of Ascalon. Overall, Cicero found himself more in agreement with Stoicism than Epicureanism. His personal brand of Platonism, like that of his teacher, probably assimilated many aspects of Stoicism, as well as Aristotelianism. However, although broadly sympathetic to this eclectic philosophy Cicero also notes its flaws. His conclusion is unclear and may be in favour of a more skeptical form of Platonism. Overall, what Cicero therefore gives us in De Finibus is a fascinating overview of several competing philosophical perspectives.

Cicero’s friend and political rival, the great Roman republican hero, Cato of Utica, is portrayed as speaking in defence of Stoicism. The series of dialogues as a whole is framed in terms of a discussion between Cicero and Cato’s nephew, Brutus, the lead assassin of the dictator Julius Caesar. However, the lorem ipsum text comes from the first book of De Finibus, in which a Roman statesman and philosopher, renowned for his Greek scholarship, Lucius Torquatus is portrayed offering a summary and defence of Epicurean philosophy as a way of life.

The Original TextSo what does the passage from which lorem ipsum comes actually say? Well the placeholder text itself is pretty garbled but the passages it occurs in (De Finibus, 1.10.32–33) basically shows Torquatus defending Epicurus’ philosophical doctrine that the most important thing in life is the experience of pleasure. This idea was widely rebuked in the ancient world, not least by Stoic and Academic philosophers such as Cato and Cicero. However, Torquatus argues that those who criticise the pursuit of pleasure do so not because they think pleasure itself is bad but because harmful consequences often follow from irrational over-indulgence. The Epicurean philosophy was more sophisticated than this, though. Epicurus proposed that wisdom consists in the rational long-term pursuit of pleasures that are natural and lasting, which he associated with practical wisdom and the attainment of supreme emotional tranquillity (ataraxia).

The central paradox of Epicureanism is that achieving lasting pleasure and freedom from pain often requires us to endure short-term pain or discomfort. We may also have to renounce certain transient pleasures for the sake of our own long-term happiness. Epicurus therefore recommended living a very simple life. For example, someone who is serious about maximising their own pleasure and who pursues it philosophically might judge it prudent to undertake vigorous physical exercise and follow a healthy diet, enduring “short-term pain for long-term gain,” as we say today. Torquatus says that the pursuit of pleasure has undeservedly acquired a bad name because people confuse the foolish and reckless pursuit of short-term pleasures with the prudent long-term pursuit of pleasure taught by Epicurus and his followers.

The whole of the relevant section from De Finibus reads as follows in H. Rackham’s 1914 Loeb Classical Library translation, with the fragments included in the lorem ipsum placeholder text in bold:

But I must explain to you how all this mistaken idea of denouncing of a pleasure and praising pain was born and I will give you a complete account of the system, and expound the actual teachings of [Epicurus,] the great explorer of the truth, the master-builder of human happiness. No one rejects, dislikes, or avoids pleasure itself, because it is pleasure, but because those who do not know how to pursue pleasure rationally encounter consequences that are extremely painful. Nor again is there anyone who loves or pursues or desires to obtain pain of itself, because it is pain, but occasionally circumstances occur in which toil and pain can procure him some great pleasure. To take a trivial example, which of us ever undertakes laborious physical exercise, except to obtain some advantage from it? But who has any right to find fault with a man who chooses to enjoy a pleasure that has no annoying consequences, or one who avoids a pain that produces no resultant pleasure?

On the other hand, we denounce with righteous indignation and dislike men who are so beguiled and demoralized by the charms of pleasure of the moment, so blinded by desire, that they cannot foresee the pain and trouble that are bound to ensue; and equal blame belongs to those who fail in their duty through weakness of will, which is the same as saying through shrinking from toil and pain. These cases are perfectly simple and easy to distinguish. In a free hour, when our power of choice is untrammeled and when nothing prevents our being able to do what we like best, every pleasure is to be welcomed and every pain avoided. But in certain circumstances and owing to the claims of duty or the obligations of business it will frequently occur that pleasures have to be repudiated and annoyances accepted. The wise man therefore always holds in these matters to this principle of selection: he rejects pleasures to secure other greater pleasures, or else he endures pains to avoid worse pains.

Although Torquatus is portrayed as defending this philosophy of life, it seems clear that Cicero was unconvinced. In the following chapters, Cato is depicted arguing in favour of the opposing Stoic position. The Stoics believed that the meaning or purpose of life is the pursuit of wisdom and virtue, first and foremost, rather than seeking pleasure or tranquillity. Then again, the Academic philosopher Antiochus’ view is presented as being that the best life consists in a combination of virtue and sufficient “external goods”, such as health, property, and friends, etc. Nevertheless, many people today continue to be drawn to Epicureanism. Maybe this is because it provides a fairly sophisticated account of one of a handful of perennial philosophies of life that recur in different forms throughout the ages.

Cicero took these conflicting philosophical views about the most important thing in life very seriously indeed and tried to carefully evaluate their pros and cons. What do you think? Was this a bad philosophy that deserved to be consigned to the dustbin of history or is the meaning of life hidden in the garbage of the lorem ipsum placeholder text?

October 3, 2024

Never enter a contest where victory is not up to you...

CommentaryYou can be invincible if you never enter a contest in which victory is not under your control. Beware lest, when you see some person preferred to you in honor, or possessing great power, or otherwise enjoying high repute, you are ever carried away by the external impression, and deem him happy. For if the true nature of the good is one of the things that are under our control, there is no place for either envy or jealousy; and you yourself will not wish to be a praetor, or a senator, or a consul, but a free man. Now there is but one way that leads to this, and that is to despise the things that are not under our control.

You can be undefeated if you only engage in contests where victory is within your power, in other words. When you see someone being honored by others or possessing great power, be cautious once again not to let your initial impression sweep you along with it, into assuming he is fortunate, but pause for thought. Don’t, in other words, allow yourself to assume that the things the majority of people crave necessarily make them fulfilled in life.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.