Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 18

May 31, 2024

Philosophy Attractions of Athens

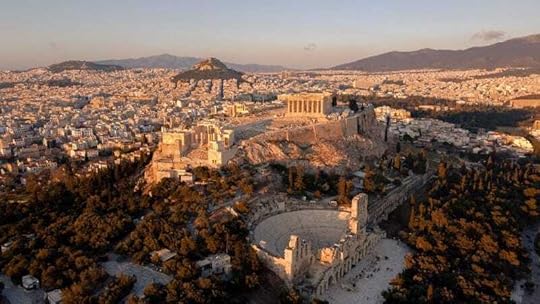

Athens, the capital of Greece, is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world. It also happens to be the home of western philosophy. Yet most tourists are unaware of the significance that certain locations in the city have for the history of philosophy.

Photo by Jim Niakaris on Unsplash

Photo by Jim Niakaris on UnsplashFriends, and strangers, who share my love of history, often ask me what locations they should visit there.

I am originally from Scotland, emigrated to Canada about eight years ago, but recently became a permanent resident of Greece. I’ve spent a lot of time exploring Athens, doing research for various books on philosophy. (My graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, depicts scenes in the Ancient Agora and Delphi.) Friends, and strangers, who share my love of history, often ask me what locations they should visit there. So I finally decided to write this short guide to Athens for fans of ancient philosophy.

One thing worth clarifying at the outset is that ancient Greece ended up becoming part of the Roman world. In 146 BC, Greece was conquered by the Roman Republic, becoming a client state and later a province of what eventually became known as the Roman Empire. Later, under the Ottoman Empire, Greece was still referred to as the “Roman nation”. Many of the archeological ruins and museum exhibits in Athens actually date not from the classical period of Pericles and Socrates, et al., but from Roman era, particularly the rule of Emperor Hadrian.

Plato’s AcademyThe Academy was one of three large gymnasia or recreational grounds in ancient Athens. It is believed to be named after a legendary hero. It contained a large grove of trees, wrestling and boxing schools, and probably running tracks, where youths would exercise naked. Older men would also gather to give speeches and discuss politics and philosophy. Socrates is believed to have discussed philosophy, walking in the grounds of the Academy. However, it is most famous for being the location where his student, Plato, later founded his school of philosophy, which became known as the “Academy” after the park in which it was located.

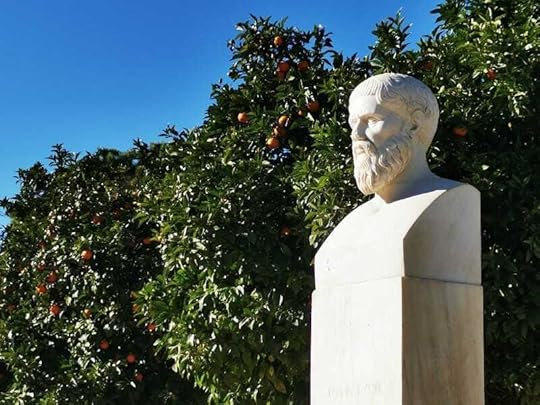

Photo of Plato’s statue in Akadimia Platonos, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of Plato’s statue in Akadimia Platonos, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThis was the first major institute of higher education in Western history, the forerunner of all subsequent colleges and universities. Now every “academy” is named after Plato’s original school. We know that Plato had a house in the grounds of the park, and taught here, although it’s not certain that he taught in a building, as philosophers often lectured while walking in the open air. There would have been shrines here, to Apollo and other gods, as well as libraries.

When you walk in Plato’s Academy Park you’re walking where Plato once walked, discussing philosophy, and where his body was eventually laid to rest.

It’s often forgotten that Plato’s tomb was also located in the grounds of this park, although no trace of it remains today. When you walk in Plato’s Academy Park you’re walking where Plato once walked, discussing philosophy, and where his body was eventually laid to rest. I’ve often wondered if a memorial could be built in the park reinstating the original epitaphs from Plato’s tomb in ancient Greek, which several ancient sources attest. Diogenes Laertius, for example, quotes them as saying:

Here lies the god-like man Aristocles [Plato’s birth name], eminent among men for temperance and the justice of his character. And he, if ever anyone, had the fullest meed of praise for wisdom, and was too great for envy.

And we’re told it was accompanied, perhaps on another part of the tomb by the following:

Earth in her bosom here hides Plato’s body, but his soul hath its immortal station with the blest, Ariston’s son, whom every good man, even if he dwell afar off, honours because he discerned the divine life.

Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, later studied philosophy here for many years, under Plato’s successors. When the Roman dictator, Sulla, besieged Athens in 87 BC, his troops sacked the buildings of the Academy and cut down its trees for timber. Roughly a decade later, Cicero, the celebrated Roman orator and statesman, visited the Academy, and describes it being completely empty. It’s worth quoting what he says in full:

When we reached the walks of the Academy, which are so deservedly famous, we had them entirely to ourselves, as we had hoped. Thereupon Piso [Cicero’s companion] remarked: “Whether it is a natural instinct or a mere illusion, I can’t say; but one’s emotions are more strongly aroused by seeing the places that tradition records to have been the favourite resort of men of note in former days, than by hearing about their deeds or reading their writings. My own feelings at the present moment are a case in point. I am reminded of Plato, the first philosopher, so we are told, that made a practice of holding discussions in this place; and indeed the garden close at hand yonder not only recalls his memory but seems to bring the actual man before my eyes.” — Cicero, De Finibus

Photo of street sign, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of street sign, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonToday the Academy survives as a large public park called Akadimia Platonos (Plato’s Academy). It is located in one of the poorer suburbs of Athens, about 20 minutes walk from the Acropolis, and the centre of the modern city. Few tourists visit the Akadimia Platonos Park but it’s popular with locals who walk their dogs, jog, and bring their children to play there. You can see the ruins of several buildings from classical antiquity, including the foundations of the palaestra or wrestling school, and a peristyle building, which could perhaps have been connected with Plato’s school. There is a statue of Plato in the nearby square, close to which there is also a small digital museum commemorating Plato’s philosophy.

When I visited Plato’s Academy Park, it surprised me that there wasn’t already an international conference centre nearby. Who wouldn’t want to attend a conference or workshop at the original location of Plato’s Academy? I started talking to my friends and colleagues about this idea and before I knew it we’d set up a nonprofit organization, registered in Greece, called The Plato’s Academy Centre, with the aim of making this dream come true. It’s still in its infancy but we’ve already created a flourishing online community as the first phase of our project to bring philosophy back to the grounds of Plato’s Academy.

Photo of ruins at Akadimia Platonos, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Lyceum

Photo of ruins at Akadimia Platonos, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe LyceumThe Lyceum was one of the other gymnasia of ancient Athens. It’s most famous as the location chosen by Aristotle, one of Plato’s students, for his own philosophy school. However, before his time, other intellectuals taught there. According to one story, Protagoras, the first and most famous of the Sophists, had his controversial book On the Gods read here, which appears to have been an early statement of agnosticism.

As to the gods, I have no means of knowing either that they exist or that they do not exist. For many are the obstacles that impede knowledge, both the obscurity of the question and the shortness of human life. — Protagoras, On the Gods

After Aristotle’s time, we’re told that Chrysippus, the third head (scholarch) of the Stoic School lectured here for a while.

Photo of ruins at the Lyceum, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of ruins at the Lyceum, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonToday, the Lyceum is a beautiful garden, which contains the ruins of a palaestra, or wrestling school. There’s a ticket office, where you must pay for entry, so the site is protected from vandals, and well looked after. It is located in Kolonaki, one of the most affluent suburbs of Athens, beside the National Gardens of Athens, and about 20 minutes walk from the Acropolis, and centre of the city.

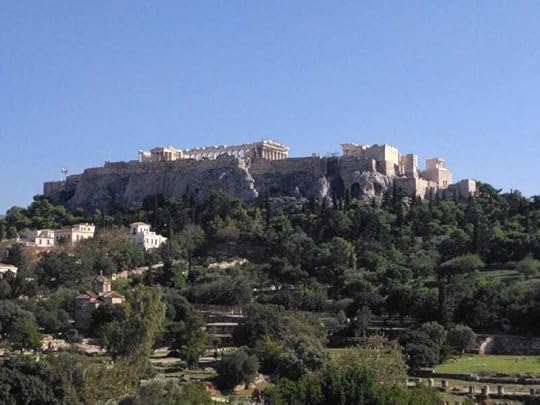

The Acropolis and ParthenonYou can’t miss the Acropolis, the huge rock at the centre of Athens, where the Parthenon, or temple of Athena Parthenos (the virgin), the patron goddess of Athens, overlooks the city. It was originally a primitive hill fort, which evolved over the centuries into a stunning temple complex, symbolizing the height of Athens’ power.

Photo of the Acropolis of Athens, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

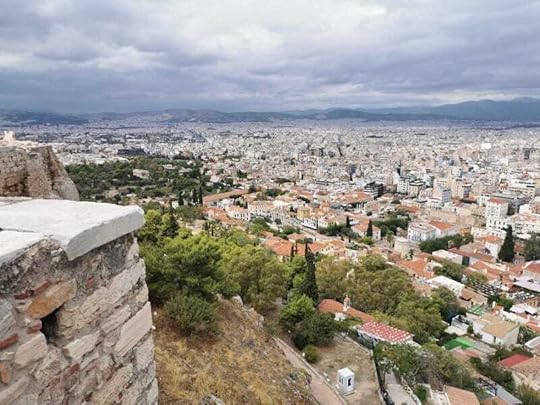

Photo of the Acropolis of Athens, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonAncient philosophers, such as Plato and the Stoics, often refer to the notion of contemplating mortal events as though seen from high above. This perspective would have been familiar to ancient Athenians as the view from atop the Acropolis, looking down on the agora, where most of the business of the city took place, far below. This is the perspective of Athena, the view from above, looking over Athens.

This is a fine saying of Plato: That he who is discoursing about men should look also at earthly things as if he viewed them from some higher place. — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 7.48

Marcus goes on to describe looking down on events of daily life, in agoras, or city centres like the Ancient Agora of Athens. In another passage, he actually mentions an acropolis:

The mind which is free from violent passions is an acropolis, for man has nothing more secure to which he can fly for refuge and in the future be unassailable. — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 8.48

Photo of the view of Athens from the Acropolis, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the view of Athens from the Acropolis, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonToday, the Acropolis is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Athens, located in the very centre of the city. There are many locations around the city from which it can be viewed in all its glory, such as at the top of nearby Mount Lycabettus. You can also buy a ticket to enter the grounds and climb up the Acropolis to visit the Parthenon.

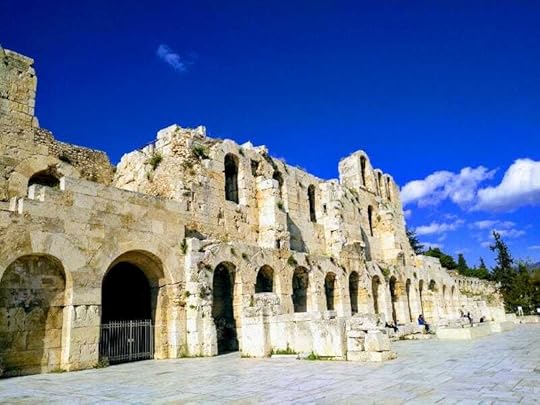

Photo of the Parthenon Temple on the Acropolis, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Odeon of Herodes Atticus

Photo of the Parthenon Temple on the Acropolis, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Odeon of Herodes AtticusThere are also a number of important archeological ruins on the slopes of the Acropolis. The Odeon of Herodes Atticus is an impressive ancient theatre, still in use today for musical performances. The Foo Fighters, for instance, recorded a concert here in 2017, and Bill Murray recently released a documentary of his musical show here. Herodes Atticus was a wealthy Greek orator, and a family friend of Marcus Aurelius. He grew up in the same household, at Rome, as Marcus’ mother.

Photo of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonHerodes was the leading figure in a movement known as the Second Sophistic, during his lifetime, the most pre-eminent Sophist, and effectively a billionaire philanthropist, responsible for several major buildings. However, he was hated by the Athenians, and frequently embroiled in controversy, e.g., being accused at one point of kicking to death his pregnant wife. During another trial, he lost his temper with Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and lunged toward him, risking being cut down by the praetorian prefect.

Marcus does not seem to have had a high opinion of Herodes. Although, he lists mosts of his main teachers in the first book of the Meditations, praising their virtues, he never mentions Herodes, despite the fact he as a family friend, and undoubtedly the most famous intellectual involved in Marcus’ education. Ignoring Herodes Atticus, Marcus instead praises a humble, unnamed slave, who looked after him and tutored him, as a small boy, in his grandfather’s household.

The Theatre of DionysusNear the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, lies the older Theatre of Dionysus, where many plays were performed, including The Clouds of Aristophanes. The Clouds ridiculed Socrates, during his lifetime, and helped fuel the gossip that led to the philosopher’s trial and execution. According to one story, some visitors from another Greek city were puzzled by the portrayal of this controversial figure on stage and asked who this man was. Socrates happened to be sitting near them in the audience and smiling, introduced himself to the whole audience, showing that he was completely unfazed by the harsh satire of him being performed on stage.

The Theatre was later restored under the Roman Empire, and sculptures from this era still stand there depicting crouching Silenos figures, which arguably bear a resemblance to earlier depictions of Socrates.

Photo of Silvanus figure from the Theatre of Dionysus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Areopagus

Photo of Silvanus figure from the Theatre of Dionysus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe AreopagusThe Areopagus is a famous rock outcrop at the foot of the Acropolis, which served as a meeting place for political councils. It is also the location of a famous New Testament episode, called the Areopagus Sermon. Curiously, in this passage, from the Acts of the Apostles, we’re actually told that St. Paul spoke to an audience of Epicurean and Stoic philosophers here, and quoted lines from the ancient Greek poet Aratus, a student of Zeno of Citium, and possibly himself a Stoic philosopher.

Photo of the Areopagus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Ancient Agora of Athens

Photo of the Areopagus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Ancient Agora of AthensThe Agora, meaning marketplace or city-centre, of ancient Athens was at the foot of the Acropolis. Socrates became associated with the agora as he chose to spend most of his time in the shops here, discussing philosophy with strangers, and his circle of friends. It is also believed that the trial of Socrates took place in the agora and that he was imprisoned and executed here.

Photo of the Temple of Hephaestus, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

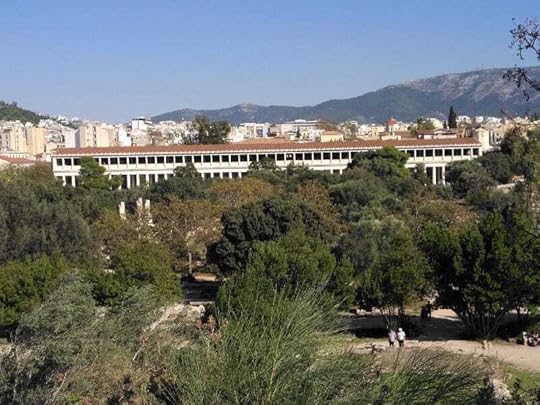

Photo of the Temple of Hephaestus, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonToday the Ancient Agora is one of the most important tourist attractions in Athens, next to the Acropolis. There is a ticket booth and you pay for entry. The grounds are full of impressive archeological ruins, including the prominent temple of Hephaestus, patron god of blacksmiths, and other tradesmen. Overlooking the Ancient Agora is a large building called the Stoa of Attalos, which is actually a modern reconstruction of an ancient Greek stoa, or colonnade, two stories tall, which houses the Museum of the Ancient Agora. This is a small museum but it contains many pieces of sculpture unearthed in the grounds of the agora, including a stunning bust of Emperor Antoninus Pius, the adoptive father of Marcus Aurelius.

Photo of the Stoa of Attalos, in the Ancient Agora, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the Stoa of Attalos, in the Ancient Agora, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonAccording to legend, Socrates spent much of his time in the shop of a cobbler called Simon. After Socrates died, Simon wrote the first Socratic dialogues, although his works are all lost today. This seemed like a fanciful myth, as Socrates was well-known for going around barefoot and placing him in a shoemaker’s shop seems deliberately ironic. However, archeologists recently unearthed cobblers nails in the ruins of a shop and, to their astonishment, nearby they also found the broken base of a kylix, or wine cup, which clearly has the name SIMON scratched upon it. This ceramic fragment can be seen exhibited in the Museum of the Ancient Agora today, and it arguably proves that Simon the Cobbler was a real person after all. Another surprising find, also exhibited in the Museum of the Ancient Agora, was a small statuette, which appears to be of Socrates himself, and was found in the ruins of the state prison, where we believe he was executed. It is as though the Athenians later felt remorse for having killed him and set up a shrine commemorating Socrates in the place where he was put to death.

The Stoa PoikileThe Stoa Poikile, or Painted Porch, was a colonnade on the edge of the Ancient Agora, facing toward the Acropolis. This is an important location because the Stoic school, which met there for centuries, was named after the Stoa Poikile. The Stoics set up their school, in other words, in the agora, among the hubbub of the city centre, where Socrates had once discussed philosophy. This perhaps marked a return to the “street philosophy” of Socrates, after Plato and Aristotle had retreated to teach in gymnasia outside the city walls.

Photo of the Stoa Poikile ruins, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the Stoa Poikile ruins, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe Stoa Poikile got its name because its wall displayed four huge paintings depicting historical and mythological battles. In a sense, it housed a small art gallery. During the life of Socrates, Athens was defeated in the Peloponnesian War, and the victors, Sparta, placed the city under the control of a military junta, called the Thirty Tyrants. The Thirty rounded up 1,400 immigrants and Democrats, seized their assets, and reputedly executed them at this location. If true, the Stoics must have realized their school met at the scene of one of the darkest incidents in Athenian history, where thousands of citizens had been summarily executed under the orders of a group of political tyrants.

Today, the ruins are in an area closed to the public, although visible through a fence. Part of the foundations of the Stoa Poikile are exposed, although the is hidden underneath adjacent buildings. Although once part of the Ancient Agora, the archeological site is separated from the rest by a train track and it is surrounded by shop and cafes on three sides. The American School for Classical Studies in Athens (ASCSA), the largest foreign archeological institute in Athens, has recently acquired some of the adjacent properties, which means they can be demolished, allowing archeologists access to the ruins underneath.

The Temple of Apollo at DelphiDelphi was a nearby city, based around an ancient Temple to Apollo, which housed the famous Pythia, or priestess of Apollo, also known as the Delphic Oracle. The oracle was the source of many famous pronouncements. Perhaps most famously, for philosophers, it was the Delphic Oracle who pronounced that no man was wiser than Socrates, when consulted by his childhood friend, Chaerephon. In the Apology of Plato, which portrays Socrates’ defence speech during his trial, this incident features prominently. Socrates claims that he was forced to begin questioning others to try to prove that they had more wisdom than him, and show the oracle must be mistaken. That was the origin of his trademark Socratic Method, or the “question and answer” approach to doing philosophy. Socrates, effectively, says that the god Apollo, speaking through his oracle, assigned him the philosophical mission, which led to his trial.

Photo of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe oracle also played an important role in the origin of Stoicism. Zeno, the founder of the Stoic school, was not an Athenian citizen but a Phoenician dye merchant, from Cyprus, who had been shipwrecked at the port of Piraeus, neighbouring ancient Athens. He traded a precious dye called Tyrian purple, made from the fermented innards of the murex sea snail. Zeno consulted the Delphic Oracle who pronounced, in typically cryptic fashion, that he should “take on the colour of dead men”. He was puzzled by this at first but eventually took it to mean that instead of dying fancy clothes purple, with dead sea snails, he should transform his own character, by dying his mind with the wisdom of dead philosophers, from previous generations. The philosopher Zeno appears to have been most impressed with was Socrates.

Photo of the archeological site at Delphi, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the archeological site at Delphi, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonThe famous maxims Know thyself and Nothing in Excess inscribed at the temple entrance became motifs in Greek philosophy…

Apollo was the patron god of the arts and, in a sense, this included philosophy. The Delphic Oracle was associated with hundreds of short maxims (typically two words each), which inspired many ancient philosophers. The famous maxims Know thyself and Nothing in Excess inscribed at the temple entrance became motifs in Greek philosophy, most notably in the Socratic dialogues. Several ancient sources also claim that the pre socratic philosopher, Pythagoras, was taught ethical philosophy by one of the priestesses of Apollo.

Today, Delphi is about two hours’ drive from Athens. It is one of the most astounding and beautiful archeological sites in the entire world, and definitely worth a visit. There is a small museum located in the grounds surrounding of the Temple of Apollo, which contains some stunning exhibits.

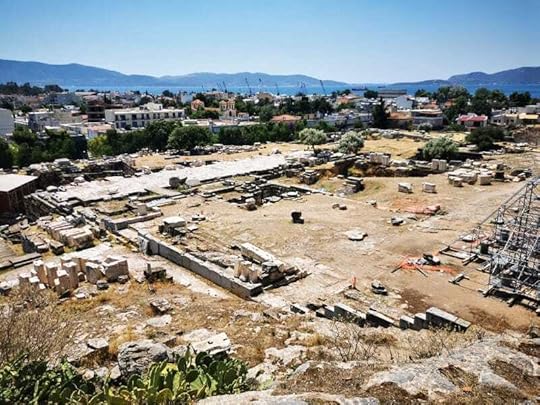

The Temple of Demeter at EleusisEleusis was also a neighbouring city, located near Athens. It was the home of the Temple of Demeter, where the main religious cult of the Greek world, the Eleusinian mystery religion, was based.

Photo of the archeological site of Ancient Eleusis, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the archeological site of Ancient Eleusis, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonDuring the First Marcomannic War, while the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was busy writing the notes that survive today as the Meditations, a tribe of nomadic Sarmatian horsemen called the Costoboci, rode all the way from their home (modern-day Romania) through the Balkans, to Eleusis, where they sacked the Temple of Demeter. Marcus swore an oath around this time that after the war he would travel to Greece, in order to be initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries there. He was true to his word and visited Athens and Eleusis in 175 CE. Marcus had the temple complex rebuilt and fortified, and a bust of him, was erected over the main gate, surrounded by poppy flowers, a traditional symbol of the goddess Demeter. That statue still survives today, and can be seen among the ruins at Eleusis. (Although recently it’s head has fallen off, or perhaps been removed for repairs!)

Photo of the bust of Marcus Aurelius at Eleusis, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the bust of Marcus Aurelius at Eleusis, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonToday, Eleusis, known as Elefsina in modern Greek, is a small town about an hour’s drive from Athens. It is a poor industrial region, lacking the splendor of Delphi. However, the ruins of the Eleusinian temple complex are quite extensive, spanning a small hill, which overlooks the nearby gulf. There is a small archeological museum at Elefsina, although I’ve never visited it because it was closed for several years, at the time when I visited.

What is Missing?I mentioned there were three main gymnasia in ancient Athens. You can still visit the ruins of the Academy and Lyceum but the third, of the Cynosarges, or “White Dog”, nothing remains, and we’re not even certain of its location. The Cynosarges was where poorer citizens, and foreign immigrants, exercised and socialized, outside the city walls. It contained a shrine dedicated to the god Hercules. Socrates’ student, Antisthenes, a forerunner of the Cynic school, used to teach here, and it may later have become associated with Cynicism — there’s an obvious similarity between the name of the gymnasia (“White Dog”) and the school (Cynic means “Dog”). There is a modern suburb called Cynosarges but it’s unknown whether this actually corresponds to the location of the original gymnasium.

You also won’t find anything remaining of the famous Garden of Epicurus, a private, walled garden located outside the city walls. It’s exact location is unknown but it was said to lie somewhere between Plato’s Academy and the Dipylon or main gate in the city walls of Athens.

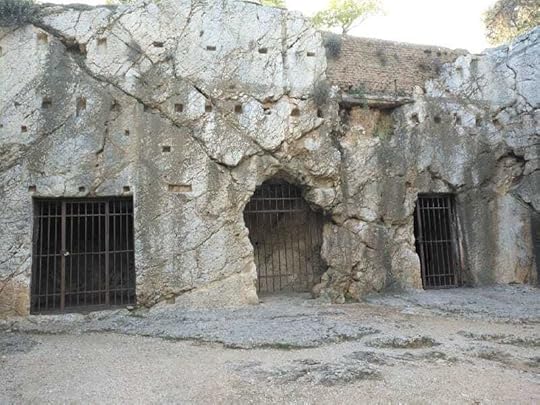

Photo of the so-called “Prison of Socrates”, taken by author, Donald J. Robertson

Photo of the so-called “Prison of Socrates”, taken by author, Donald J. RobertsonYou may also stumble across a small cave in the slopes of Philopappos Hill, signposted as “The Prison of Socrates”. This is based on folklore and whatever purpose the cave originally served, there’s no evidence to suggest it was actually the prison of Socrates. Indeed, it is believed that Socrates was held in the state prison located in the middle of the Ancient Agora, the ruined foundations of which still exist today.

ConclusionLet me know in the comments if you think I’ve missed anything, and I’ll be happy to update the article. I’ve only dealt with the locations of archeological ruins here and haven’t mentioned various other museums, which contain exhibits of interest to students of philosophy. The two best museums in Athens, in my opinion, are the Acropolis Museum and National Archeological Museum. The Benaki Museum and Numismatic Museum are also worth visiting, as is the Museum of Cycladic Art, although it relates to an earlier period in Greek history.

I hope you get a chance to visit Athens and see some of these amazing historical locations, especially the Acropolis, Agora, and nearby Delphi and Eleusis. If you’re interested in bringing philosophy back to Plato’s Academy Park, check out our Plato’s Academy Centre nonprofit startup, particularly the page explaining ways you can support the project.

Video: Donald Robertson and Ryan Holiday

Here is the full video of my recent conversation with Ryan Holiday at his Painted Porch bookshop in Bastrop, Texas. We spoke for nearly two and a half hours, mostly about Marcus Aurelius, anxiety, psychotherapy, and “Broicism”. Ryan asked me about my new biography, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 28, 2024

The Use of Mirrors in Ancient Philosophy

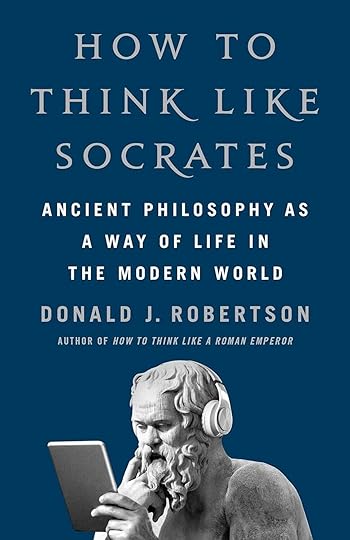

My new book, How to Think Like Socrates, includes a remarkable conversation between Socrates and the Athenian noble Alcibiades (based on Plato’s Alcibiades I). In it, Socrates claims that the famous maxim inscribed outside the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, “Know thyself” (Gnothi seauton), can best be understood by imagining that Apollo has instructed the eye to see itself.

They agree this would normally require a mirror, although Socrates notes that we can glimpse our reflection in the eyes of another person. Ironically, the eye is the only part of their body in which we can see our own gaze reflected back. In the excerpt below, Socrates develops this strange observation into a metaphor for the way in which the mind may come to “know itself” by glimpsing a reflection of itself, especially its own errors, in another person with whom we engage in philosophical dialogue.

it struck me that there are several interesting references to mirrors in ancient philosophy

As I was writing about this, it struck me that there are several interesting references to mirrors in ancient philosophy, sometimes quite literal rather than metaphorical. First of all, according to Diogenes Laertius, Socrates himself reputedly said that young men should frequently look in mirrors for one of two reasons. If they are lucky enough to be handsome, by gazing in the mirror they should remind themselves to make their conduct as beautiful as their appearance. If they are not handsome, they should look in the mirror as a reminder that they may compensate for their appearance by improving their character. (Plutarch reports the same anecdote about Socrates.)

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Diogenes Laertius also reports that Plato, who disapproved of excessive wine-drinking, advised those who got drunk to look at themselves in a mirror. He believed that by becoming more aware of their appearance, and thereby developing self-awareness, they would then abandon the habit of drinking to excess, as it made them seem ridiculous.

Diogenes Laertius claimed that Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, likewise used mirrors to help young men achieve self-awareness. Once, when a youth was asking questioning someone in a rather impertinent way, Zeno led him to a mirror and asked him to look at his reflection for a moment. Then he asked: “Does it seem appropriate for someone who looks as you do to ask such questions?”

Seneca says that his teacher Sextius remarked that some angry men have been snapped out of their rage by bringing them before a mirror and confronting them with the ugliness of their appearance (Letters 36). Seneca himself doubts this happens often because the truly enraged, he thinks, believe that their angry appearance is a good thing.

However, the same technique is described more favorably by Plutarch in On the control of anger. He says he would be grateful to a “clever companion” who held up a mirror to him during his moments of rage.

For to see oneself in a state which nature did not intend, with one’s features all distorted, contributes in no small degree toward discrediting that passion.

In other words, it seems that the idea of literally holding up a mirror to ourselves, and contemplating our own behavior, was a recurring theme in ancient philosophy.

Stoic Mirror by Rocio de TorresExcerpt from How to Think Like Socrates

Stoic Mirror by Rocio de TorresExcerpt from How to Think Like Socrates[Socrates was talking to Alcibiades.] “If you were to follow the advice inscribed at Delphi to Know Thyself,” he said, “you would care for your soul more than your property, and outdo, in that regard, even the kings of Sparta and Persia.” Socrates explained that as our true nature lies in the mind and not the body, to know oneself surely means to know the mind. Alcibiades looked intently at him. “We need to be clear about what we are, and how best to care for ourselves, if we’re to follow that famous maxim,” said Socrates, “but I think we’ve failed to understand its true significance.” “What can you possibly mean?” asked Alcibiades.

Socrates furrowed his brow and peered out from under his bushy eyebrows. “The inscription, it seems to me, advises us to know ourselves in no ordinary way,” he said, “and I can only compare it to an unusual feature of the human eye.” He leaned in a little, raised his head, and looked directly at Alcibiades. “Suppose,” he continued, “that instead of instructing you to know yourself, Apollo instructed your eye to see itself.” “I would imagine he meant,” said Alcibiades, “that the eye must look at something in which it could perceive its own image, such as the reflection in a mirror.” “Indeed,” replied Socrates, “but an image of our face may also appear when we look at the face of another person.” Alcibiades thought for a moment before exclaiming, “Yes, that’s right, we can sometimes glimpse our own reflection in the pupil of their eye!” Socrates was impressed. “So an eye looking at an eye, indeed at its very center,” asked Socrates, “would see its own image?” Alcibiades nodded in agreement. Amused by this idea, he began shifting a little as they spoke, trying to glimpse his own reflection in Socrates’s eyes.

“Indeed, the eye sees itself only when it looks directly into the other’s pupil, the very part capable of vision,” said Socrates. “Likewise, the soul knows itself only when it looks directly into the soul of another, at the part capable of knowledge. When we examine another’s capacity for wisdom, we provide ourselves with the purest mirror available among mortals,” said Socrates. Alcibiades was fascinated. “By this means,” concluded Socrates, “we may best do as the Delphic maxim advises and come to know ourselves.”

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 23, 2024

Podcast: Ryan Holiday and Donald Robertson

I went to Austin Texas, a few weeks ago to meet Ryan Holiday and we recorded two hour-long episodes for his Daily Stoic podcast. This is our first conversation, about Marcus Aurelius as Stoic and Roman Emperor. Hope you enjoy. If you like the podcast, please check out my latest book, a new biography called Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You can listen via:

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 21, 2024

The Most Famous Stoic Argued that Kindness is More Manly than Anger

Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Just be one! — Meditations, 10.16

Over the past few decades, there’s been a resurgence of interest in Stoicism. People often confuse stoicism (lower-case), a coping style that involves suppressing or concealing emotions, also called having a “stiff upper-lip,” with Stoicism (capitalized), the ancient Graeco-Roman school of philosophy. Some crudely equate “manliness” with being tough and unemotional (lower-case “stoicism”). I think there’s a more nuanced way to understand how Stoic philosophy might inform a modern man’s conception of his role in society.

Photo: chrisinthai/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Photo: chrisinthai/iStock/Getty Images PlusThe most famous ancient Stoic is Marcus Aurelius, who was emperor of Rome during the height of its power. (I wrote about his use of Stoicism in my book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.) Marcus was the closest thing the world has ever witnessed to Plato’s ancient ideal of the philosopher-king. Indeed, we’re told that he frequently quoted Plato: “that those states prospered where the philosophers were kings or the kings philosophers.”

He did have enemies, though. In 175 AD, toward the end of his reign, Marcus faced a civil war when the governor-general of the eastern provinces, Avidius Cassius, had himself acclaimed as a rival emperor by the Egyptian legion. Cassius was a cruel general, known to torture his prisoners of war and deserters alike. He criticized Marcus for being a weak and unmanly ruler, calling him “a philosophical old woman.” After only three months, however, Marcus won the civil war when Cassius’ own officers ambushed and beheaded him. No statues of Cassius survive today and his name is all but forgotten. It would seem that Cassius’s brutal brand of masculinity was not in fact a more efficient leadership style than Marcus’ philosopher-king approach.

Marcus actually tackles the question of masculinity head-on in his personal notes on Stoic philosophy as a way of life, known today as Meditations. Here’s what we can learn from the ancient text.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Manliness and fatherhoodMy impression is that Marcus inherited certain old-fashioned Roman values from his immediate family, particularly his mother, Domitia Lucilla. Despite being an immensely wealthy and highly educated Roman noblewoman, she preferred a simple way of life “far removed from that of the rich” (Meditations, 1.3). She seems to have been good friends with Junius Rusticus, who became Marcus’ main Stoic tutor. I sometimes wonder whether it could have been Marcus’ mother who first introduced him to the study of Stoic philosophy, which came to shape his concept of what it means to be a man.

Tragically, his father died when Marcus was a child, perhaps as young as three years old. We don’t know the circumstances. Marcus only knew him through early childhood memories and what he learned from family and friends about his father’s reputation, which he sums up in just two words: “modesty and manliness” (Meditations, 1.2). Other Roman nobles would have regarded “modesty” as evidence of weakness. Marcus, on the contrary, saw the modesty for which his father was known as a sign of his manliness and strength of character.

For Marcus, the ability to show kindness and compassion toward others, rather than wallowing in anger, was one of the most important signs of true inner strength and manhood.

Although he lost his father before he even had a chance to know him, Marcus was fortunate to be adopted as a teen by a Roman noble destined to become the emperor known as Antoninus Pius. Marcus made Antoninus Pius his role model in life and decades after his adoptive father’s death Marcus would still describe himself as a “disciple of Antoninus.” Meditations lists in great detail the qualities Marcus most admired in his adoptive father and sought to emulate. The first thing he mentions is that Antoninus was “gentle.” He was “never harsh, or implacable, or overbearing,” and never worked himself up into a lather over anything (Meditations, 1.16). For Marcus, the ability to show kindness and compassion toward others, rather than wallowing in anger, was one of the most important signs of true inner strength and manhood.

Manliness and mastering angerIn Meditations, Marcus goes into detail about Stoic strategies for mastering our feelings of anger. He concludes by saying something remarkably ahead of its time:

And when you do become angry, be ready to apply this thought, that to fly into a passion is not a sign of manliness, but rather, to be kind and gentle. For insofar as these qualities are more human, they are also more manly. It is the man who possesses such virtues who has strength, nerve, and fortitude, and not one who is ill-humoured and discontented. Indeed, the nearer a man comes in his mind to freedom from unhealthy passions [apatheia], the nearer he comes to strength. Just as grief is a mark of weakness, so is anger too, for those who yield to either have been wounded and have surrendered to the enemy. — Meditations, 11.18

Marcus, like other Stoics, didn’t believe that all feelings of anger and grief are signs of weakness. The Stoics accepted that there is a type of emotional reaction that’s inevitable in certain situations. Here, he’s talking about what they called the unhealthy passions, feelings such as fear or grief that someone indulges in and magnifies beyond the bounds set by nature. The wise man, by contrast, doesn’t add to this initial spark of anger or perpetuate it any further. To do so, according to Marcus, is a sign of true weakness. Although he seemed like a powerful figure, the cruel usurper Avidius Cassius was, in this sense, actually a very weak man. He lacked the strength of character and freedom from passionate grief and anger (apatheia) exhibited by Marcus’ birth father and role models such as his adoptive father, Antoninus.

To be more manly, you must first be more humanOne of the pitfalls of defining manliness is the potential implication that women don’t possess the qualities you’re describing. The Stoics avoided that by insisting that the virtues are fundamentally the same in men and women. However, they manifest in superficially different ways in each of us, depending on our nature and circumstances. It would be more accurate to say that Marcus is describing prerequisites for manliness, required for humans to fulfill their nature properly — “insofar as these qualities are more human,” as he puts it, “they are also more manly.” Stoics believed that anyone, whether male or female, required this moral and practical wisdom in order to reach their potential in life.

Elsewhere, Marcus affirms his desire to live up to Antoninus’ example and become “one who is manly and mature, a statesman, a Roman, and a ruler” (Meditations, 3.5). To him this means being able to perform his duties, and even face death, in good cheer, without being dependent upon support from others. He sums it up in the maxim: “you must stand upright, not be held upright.” Marcus repeated this striking expression of self-reliance three or four times in Meditations. Finally, he condensed it into just three Greek words:

Ὀρθός, μὴ ὀρθούμενος

“Upright, not righted (by others)” (Meditations, 7.12). That’s the sort of man he admired and wanted to become. Someone with the strength of character to stand on his own two feet and, like his adoptive father Antoninus before him, to repay even anger with unshakeable wisdom, patience, and kindness.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 14, 2024

From the Mother of Caesar

From my mother [I learned], piety and kindness, and abstinence, not only from evil deeds, but even from evil thoughts; and further, simplicity in my way of living, far removed from the habits of the rich. — Marcus Aurelius

Although it goes unmentioned in Marcus’s brief character sketch of his mother, Lucilla exhibited another notable virtue: natural affection. Marcus came to agree with his rhetoric tutor, and family friend Marcus Cornelius Fronto, who claimed that generally speaking, “those among us who are called Patricians are rather deficient” in precisely this quality.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Wealthy Roman slaveowners and the baying audiences at gladiatorial contests may appear to have been numb to human suffering. However, individuals can always be found who stand apart from their contemporaries. The Greek word Marcus and Fronto used of such people, philostorgia, which normally refers to the love of close family members for one another, is central to Stoic ethics. Philostorgia is sometimes translated as “natural affection,” “parental love,” or “familial love,” although we might best describe it as resembling the Christian concept of brotherly love. Paul equates the two terms in the New Testament when, for instance, he says: “Be kindly affectionate [philostorgoi] to one another with brotherly love [philadelphia].”

“Aurelius and his mother” by Arthur Hughes (1868)

“Aurelius and his mother” by Arthur Hughes (1868)The Stoics believed that such “natural affection” should extend to everyone, as all rational beings are viewed by the wise as their brothers and sisters. In his letters, Fronto more than once makes the striking claim that the Latin language has no equivalent word for philostorgia, as in his description of a friend:

“His characteristics, simplicity, continence, truthfulness, and honour plainly Roman, a warmth of affection, however, possibly not Roman, for there is nothing of which my whole life through I have seen less at Rome than a man unfeignedly φιλόστοργος [philostorgos]. The reason why there is not even a word for this virtue in our language must, I imagine, be, that in reality no one at Rome has any warm affection.”

It is clear from Fronto’s correspondence that he viewed Marcus and Lucilla as exceptions, among the few patricians in Rome who were capable of exhibiting the natural affection held in such regard by philosophers. Indeed, Marcus’s warmth and toward his friends is displayed throughout the correspondence with his Latin master. He even praises Fronto, on one occasion, by comparing his eloquence to Lucilla’s.

[Excerpt from Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, now available from Yale University Press in paperback, hardback, ebook, and audiobook formats.]

If we can see beyond Fronto’s rather shameless toadying, his letters provide us with additional insights into Lucilla’s character and her influence upon her son. Fronto celebrates the virtues for which Marcus’s mother was known in a letter he sent her on her birthday in which he compares her to Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom. He portrays Lucilla as a woman known for having had great love, or natural affection, toward her husband, and for loving her children. The letter suggests that she is seen as virtuous yet modest, good-natured, approachable, and kind. She is also portrayed as a straightforward, honest woman.

Fronto concludes by saying that he would bar from Lucilla’s birthday celebrations any persons who made “a pretense of good-will” and were “insincere,” those for whom everything from laughter to tears was make-believe, and who, as Homer’s Achilles put it, hid “one thing in their hearts while their lips speak another.” Fronto apparently did not see himself in this description, but it surely conjured to mind other rhetoricians of his and Marcus’s acquaintance. He would certainly have insisted that Marcus read his mother’s birthday letter, so it is likely that its portrayal of her met with her son’s approval. Lucilla emerges, in Fronto’s highly contrived compliment, as a woman known for her familial affection, honesty, and, perhaps ironically, for her straight talking.

Marcus recognized that these qualities clashed at times with the culture of the Second Sophistic, which elevated insincerity and sycophancy to an art form, and Fronto was arguably not much better than the Greek Sophists in this regard. His birthday letter could be dismissed as mere flattery, but it echoes what Marcus said about his mother privately in the Meditations. Fronto was right: the woman who taught her son not only to avoid doing wrong but to avoid even contemplating a wrong action inwardly would doubtless “hate like the gates of hell” hypocrites of the sort denounced by Achilles in Homer’s Iliad. It is no surprise that such a woman would rear a son who became famous for his love of truthfulness.

[Excerpt from Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, now available from Yale University Press in paperback, hardback, ebook, and audiobook formats.]

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 9, 2024

How Stoicism can Save Democracy

This special episode contains a live recording of my recent talk for Conversations with Modern Stoicism, hosted by . We were celebrating Marcus Aurelius’ birthday, and I spoke at length about what I think we can learn from ancient Greece about the dangers faced by democracy, and how Socrates and the Stoics could help us. I was speaking live from Athens, the birthplace of democracy. Thanks to Phil Yanov, for providing the audio recording for this podcast episode.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Do not wish for things that are not up to you...

CommentaryIf you make it your will that your children and your wife and your friends should live forever, you are silly; for you are making it your will that things not under your control should be under your control, and that what is not your own should be your own. In the same way, too, if you make it your will that your slave-boy be free from faults, you are a fool; for you are making it your will that vice be not vice, but something else. If, however, it is your will not to fail in what you desire, this is in your power. Wherefore, exercise yourself in that which is in your power. Each man’s master is the person who has the authority over what the man wishes or does not wish, so as to secure it, or take it away. Whoever, therefore, wants to be free, let him neither wish for anything, nor avoid anything, that is under the control of others; or else he is necessarily a slave.

If we’re to embrace reason then we have to be brutally honest with ourselves about everything. Yet the majority of us live in denial of the fact that life is fleeting and the things and people we love will one day be gone. The Stoics believe that if we’re completely realistic about this, though, we’ll actually be able to love others more honestly and with wisdom as well as natural affection.

May 7, 2024

Robert Burns and Stoicism

It was the precepts of this school which rendered the supreme power in the hands of Marcus Aurelius a blessing to the human race… — Dugald Stewart

Robert Burns (1759–1796), the national bard of Scotland, was good friends with Dugald Stewart (1753–1828), a professor of philosophy at Edinburgh University, and an expert on Stoicism.

According to Stewart’s own account, he was first introduced to Burns in 1786. Burns died in 1796, aged only thirty seven, so he appears to have remained friends with the philosopher throughout the last decade of his life. Stewart clearly knew Burns well, and provides a detailed sketch of his friend’s character. He says that Burns gave him handwritten copies of several of his favorite poems, namely On turning up a Mouse with his Plough, On the Mountain Daisy, and The Lament.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Why did Burns specifically choose these three poems to share with Stewart? Although he never mentioned Stoic philosophy in his writings, these poems contain themes of transience, acceptance, and resilience, which seem to resonate with aspects of Stoicism. Burns surely discussed these poems, and others like them, with his friend, Stewart, who, being an expert on Stoicism, would have realized, and perhaps noted, their relevance to the philosophy.

The poet Robert Burns, national bard of Scotland

The poet Robert Burns, national bard of ScotlandIn this article, I’ll examine To a Mouse, the most famous of the three. It was written in 1785, the year before Burns was introduced to Stewart. Burns wrote mainly in the Broad Scots dialect but, for our purposes, I’ll be explaining what his words mean when translated into modern English. First, to give you a flavour of the poem, and set the stage, I’ll quote the opening stanza in its original form:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedWee, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie,O, what a pannic's in thy breastie!Thou need na start awa sae hasty,Wi' bickering brattle!I wad be laith to rin an' chase thee,Wi' murd'ring pattle!Burns was a farmer and his poetry typically contains rustic, agrarian imagery. To a Mouse opens with Burns accidentally disturbing the nest of a field mouse while plowing. The tiny animal is startled and darts away in fear, even though Burns means it no harm.

Burns evokes this simple but powerful image in order to reflect on the analogy with his own life, referring to himself in the following lines as the mouse’s “poor earth-born companion and fellow mortal”. He is the mouse. In fact, we are all, in a sense, living lives as fragile as that of this tiny creature.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedThy wee bit housie, too, in ruin!One moment the mouse was feeling safe and secure, content in his cozy little nest, the next it was suddenly upended by the plow, without warning, and scattered to the winds, forcing him to flee in terror. After having spent so long building his home, one tiny piece at a time, it was gone in a moment, destroyed by forces beyond his control.

The neoclassical monument to Dugald Stewart on Calton Hill in Edinburgh

The neoclassical monument to Dugald Stewart on Calton Hill in EdinburghBut, says Burns to the mouse, you are not alone in discovering that our attempts at foresight may turn out to be completely in vain. I’ll quote the best-known lines of the poem in Scots:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedThe best-laid schemes o' mice an' menGang aft agley,An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain,For promis'd joy!In other words, mice and men are alike in that even their most careful plans may be thwarted. We hope for pleasure, but despite everything, we may be confronted instead with anxiety and suffering. External events are never entirely under our control.

Having opened with a simple rural image, Burns emphasizes the analogy between the mouse’s life and his own in the following lines. In the concluding stanza, however, Burns arrives at a more explicitly philosophical conclusion. Humans suffer in ways, which mice do not.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedStill thou art blest, compar'd wi' meThe present only toucheth thee:But, Och! I backward cast my e'e.On prospects drear!An' forward, tho' I canna see,I guess an' fear!In these lines, Burns echoes an observation also made famous by the Stoic philosopher Seneca. Animals dwell in the present moment, where they may suffer due to misfortune. Humans go beyond this both by worrying about the future, and ruminating on past misfortunes.

Two elements must therefore be rooted out once for all—the fear of future suffering, and the recollection of past suffering; since the latter no longer concerns me, and the former concerns me not yet. — Seneca, Moral Letters, 78

The end of the poem can seem bleak, and may reflect Burns’ worries about his own precarious situation in life. We are, indeed, even worse off than the mouse. And, conversely, the mouse is better off than us. It is possible, therefore, find a glimmer of optimism in the conclusion: perhaps if we can learn to live more in the present, like the mouse, we may at least alleviate some of our suffering.

It is indeed foolish to be unhappy now because you may be unhappy at some future time. — Seneca, Moral Letters, 24

After Stewart received a handwritten copy of To a Mouse from the poem’s author, it’s tempting to speculate that he and Burns may have discussed well-known passages such as these, found in the writings of Seneca and other ancient Stoic philosophers. We can only imagine the conversations about poetry and philosophy that these two friends had as they strolled together through the Scottish countryside.

Portrait of the Scottish philosopher Dugald Stewart

Portrait of the Scottish philosopher Dugald StewartThank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 6, 2024

Get 50% off Marcus Aurelius

Yale University Press (YUP) is having a sitewide sale from May 6th-17th. Books are 50% off and shipping is free. NB: Offer applies to orders of print editions from customers in US and Canada only. Additional terms and conditions apply. See this web page for details. Use the special code Y24SAVE50 to claim your discount.

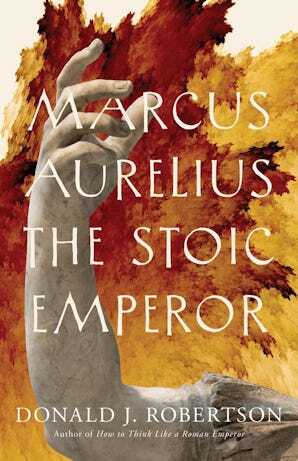

Order Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor

This offer includes the hardback edition of my latest book, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, which is part of YUP’s Ancient Lives series.

“[Robertson] thoughtfully and readably capture[s] the essence of this great man and his great life. It’s a must read for any aspiring Stoic.”—Ryan Holiday, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Daily Stoic

“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of The Pocket Stoic

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.