Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 19

May 4, 2024

Win an Advance Copy of How to Think Like Socrates

Would you like to win a copy of How to Think Like Socrates? My publisher, St Martin’s Press, have generously agreed to give away twenty-five print copies of the book. Offer ends May 30th, and is open only to residents of the US and Canada. (Stay tuned for other offers if you live elsewhere!)

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What other authors have said…This is an intriguing and original book, as well as being engagingly written and highly accessible. It is innovative both in linking the Socratic dialogues, especially those of Plato, with their historical context and in highlighting the significance of Socratic philosophical enquiry for modern readers. The connection made between Socratic method and CBT psychotherapeutic guidance is particularly suggestive. — Christopher Gill, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Thought, Exeter University, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance

Donald Robertson creates a wonderful semi-fictionalized Socrates to introduce modern readers to the birth of philosophy in Athens. We experience first-hand the method Socrates made famous — of subjecting our deepest beliefs to a cross-examination that jolts and stings like an electric ray. In our modern world that swirls with disinformation and unreason, we need nothing less to awaken us from our illusions. — Nancy Sherman, Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, and author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! Wisdom isn’t a rulebook but a mindset. It develops from a life of honest and courageous inquiry. Donald Robertson masterfully and vividly takes us back to the Athens of Socrates and recreates the setting as well as he does the powerful ideas that one place, time, and person launched into the world forever. It’s an introduction to philosophy as a way of life that’s as gripping as any novel, and is as novel as a philosophy book can be. Highly recommended! — Tom Morris, author of Philosophy for Dummies and Stoicism for Dummies

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

May 2, 2024

The Stoic Mindset in Sports and Life

In this episode, I speak with Mark Tuitert. Mark is an Olympic gold medallist in speed skating. He is the author of a new book called The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of Stoicism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Highlights

HighlightsHow Mark’s accomplishments in speed skating shaped his life

How he first become interested in Stoicism and Marcus Aurelius inspire you

How do you Stoicism helped Mark as an athlete

What do you think were the key things that helped you deal with your own anger?

What do you think the relationship is between the sporting or Olympic mindset and the Stoic mindset?

What’s your favorite exercise from the book and why?

How do you feel about the experience of being in Athens and visiting the home of philosophy?

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 30, 2024

Responding to Critical Reviews of "Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor"

Some people say you should never read negative reviews. I disagree. I love reading all reviews, good or bad. How can we grow as writers or creators if we ignore our audience? In this recent video, Jerry Seinfeld, likewise, talks about his love of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations and how he learned to enjoy reading critical reviews of his work. We can benefit a lot from critical feedback, as long as we receive it wisely.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I’ve been lucky that all of my books have been pretty well-received. My most recent is a biography called Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, for Yale University Press’ Ancient Lives series. It currently has 4.27 stars from 139 reviewers on Goodreads, and 4.7 stars from 71 reviewers on Amazon, plus 4.7 from 21 reviews on Audible US — that’s quite good compared to my other books. I’ll respond to excerpts from reviews below but link to the original in case anyone thinks I’m taking them too much out of context. I assume that no book is perfect, and everything can be improved. And I also find that reflecting on criticisms can often help to bring to light some interesting observations about the writing process and the content of the texts themselves. So here are my thoughts about all of the criticisms of Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor that people have made so far…

What reviewers didn’t like…

What reviewers didn’t like……those more interested in Stoicism rather than a prosaic biography of Marcus would be better served by reading Mediations itself, Discourses by Epictetus, a collection of Seneca’s letters, and How To Think Like a Roman Emperor (3/5 stars and also by author Donald Robertson*). In fairness to Mr. Robertson, a focus on Stoic philosophy in this book might have made it too similar to his other aforementioned work. — Goodreads

I can’t argue with the conclusion. I agree that you’d be better off reading the Meditations, or other primary sources, if your goal is to learn more about Stoic philosophy. I’m not sure about the premise, though: that this book should deliver more philosophy. This is very much a biography — and part of a series of ancient biographies. So don’t expect it to provide a comprehensive account of Stoic philosophy. Compared to other biographies of Marcus, this one was intended to link his life more to his philosophy, and I think it achieves that to some extent. But it’s definitely not intended as a substitute for reading the Meditations. Could we signal more clearly to readers that it’s a biography and not a textbook on philosophy? I don’t think so, to be honest — it seems pretty clear to me from the cover — but maybe I’m wrong.

Could it have been a biography of Marcus, though, that also includes a lot more philosophy? Well, that’s possible, although there’s a limit to how many words the books in this series could be (as with most books). The primary goal is for it to be a comprehensive biography so to also go into much more depth about the philosophy we’d need a bigger book, which wouldn’t have been possible within the parameters of this series, unfortunately. Of course, I think the solution, if you want both a biography and a book on Stoic philosophy, is simply to read two books: perhaps this one and How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, or another introductory text on Stoic philosophy.

Maybe I should read it and not listen. The narrator's voice was pleasant, but I think I might have focused better seeing the names.— Goodreads

Not everyone likes my voice, to be fair. So it’s good that this reviewer does. It doesn’t seem like a criticism of the book per se but perhaps underneath this comment there is one: that there are too many Latin (and Greek) names. That’s a tricky one. We did try to reduce those, believe it or not, but if we’re going to do a thorough biography, it’s hard to avoid mentioning names of places and people quite a lot. For a Roman emperor, those are going to be mostly Greek and Latin, unfortunately. We did put quite a bit of effort into simplifying many names by abbreviating them, choosing to use slightly Anglicized pronunciation where appropriate, or using other devices.

I liked Verissimus better. This was a bit dry and repetitive. Kudos on the scholarship. Would have liked more about the philosophy, along with the details about the successive campaigns. — Goodreads

I’m glad the reviewer liked Verissimus, my graphic novel about Marcus Aurelius. Different books appeal to different people. Verissimus and Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor are completely different styles of book. (There are probably other people who would prefer this book and dislike Verissimus.) I would describe my writing style as deliberately melodramatic, so I’m sure some people would find it dry — that’s always a risk with ancient history and philosophy — but I’d be more inclined to expect the opposite criticism. It’s a very conscious choice that I make to use language and certain literary devices to make my books about history more dramatic than normal. That style of writing isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but I’ve been pleasantly surprised to find that most people seem okay with it.

I do think my nonfiction writing can be repetitive — there are usually technical reasons for that, e.g., when talking about how to apply Stoicism or CBT to different emotions there’s a lot of overlap so it can be a serious challenge to avoid repetition. I’m not sure how this biography repeats itself, though — in the editorial process we searched for any redundancy and tried to weed out anything that was said more than once. (Except for maybe two instances, where it was deemed necessary.) The question about including more philosophy was touched on above: I think if we want the biography to be as complete as possible, we’d need a longer book for that, which wasn’t possible within the constraints of this series. As for more details on the military campaigns, that’s more or less all the information we have. (Although it’s always possible to flesh them out more by drawing on general information about legionary equipment and tactics, and so on.) Also, I think that going into much more detail about military campaigns, may perhaps have turned off some other readers, who aren’t into that side of things.

A short biography of the philosopher/king of ancient Rome. Here the reader is given the facts as known (and much is unknown) about the life led by Marcus Aurelius. However, it is not a book for delving deep into his stoical philosophy. After putting down this book, I thought why did I take my time to try to understand some obscure and ancient conflicts (such as the one with Cassius the Usurper)? — Amazon

It’s 50k words, which is an average length book. That might be shorter than people expect for some biographies, though. It’s the same as the rest of the Ancient Lives series. Do we know much about Marcus? It’s relative to your expectations. We know little about most ancient figures, compared to modern ones, of course. Overall, I think most historians would say we are actually fortunate to know quite a lot about Marcus Aurelius — almost all of which is covered in this book. In fact, we probably know more about Marcus than we do about any other ancient philosopher, certainly more than we do about any other Stoic philosopher. That’s because he was also an emperor, so records exist of his rule, as well as inscriptions, statues, monuments, legal digests, and correspondence, etc.

Again, if you really want a deep dive into Stoic philosophy, yes, you’d be better to read a book dedicated to that subject, rather than a biography of Marcus Aurelius. I can see why someone might think “Do I care about the civil war with Avidius Cassius?” That’s a key part of Marcus’ biography, though, so it really just comes down to whether you’re interested in finding out about the events of Marcus’ life, and his relationships with other people, or you’re looking for something else from the book. I have found, from the courses I run on Marcus’ life and philosophy, that people who are really interested in the Meditations tend to say they get a lot more from the text once they’ve learned more about Marcus’ biography. Some reasons why that might be the case are obvious: Marcus mentions lots of other people in book one so knowing who they are and what his relationship with them was like makes it easier to understand what he is writing about. Avidius Cassius isn’t mentioned in the Meditations but I think knowing that, at that time, he was Marcus’ general, and probably a friend of sorts, who would later betray him and start a civil war, sheds a different light on many of the passages from the Meditations, such as 2.1, perhaps the most famous of them all, where Marcus tells himself to prepare each day to deal philosophically with people who may be deceitful or treasonous… such as Cassius.

Nothing to dislike, however the narrator was rather monotone and the book was heavy with names and places. Already aware of Marcus and his stoic ethos, I had hoped to put more detail and colour to his character, but I felt this was in relatively short supply. In some respects I felt that I got to know Hadrian and Lucius better than I did Marcus. Nevertheless, an informative listen overall. — Audible

A couple of people have said my delivery is monotone but actually I more often get the contrary criticism that my accent makes my delivery slightly sing-song, and some people don’t like that. I’m lucky that despite having an accent, the majority of listeners seem to quite like my delivery. It’s not to everyone’s taste, though. We do make a conscious effort when in the studio to vary the tone of certain passages, and the producer may ask me to do several takes of them specifically for that reason.

Again, we tried to simplify and reduce the foreign names but that’s bound to happen with an ancient biography, to some extent. I do concur somewhat that we learn more about Hadrian and Lucius in some ways. That’s because the ancient histories tend to contrast characters. Marcus is portrayed as calm and reasonable, and they highlight that by contrasting him with more erratic and unreasonable men, such as his adoptive brother Lucius Verus. Stories about calm and reasonable men can often seem, well, boring. It’s the crazy ones, usually, who make stories more colourful. So we learn about Marcus by setting his behaviour in a social context, in relation to more dramatic characters.

I made a decision to say more than normal about Hadrian because I thought the contrast highlighted important aspects of Marcus’ life and character, which have been somewhat overlooked in previous biographies. To be quite blunt, I believe that Marcus’ character was profoundly affected by the loss of his father, when he was a small boy, and being taken under the wing of Hadrian was probably quite traumatic for Marcus, as a teenager. I think his horror at Hadrian’s purges, and other excesses, was one of the things that drove Marcus into the arms of Stoic philosophy, and explains his psychological development.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 25, 2024

Let people think you’re a fool...

CommentaryIf you wish to make progress, then be content to appear senseless and foolish in externals, do not make it your wish to give the appearance of knowing anything; and if some people think you to be an important personage, distrust yourself. For be assured that it is no easy matter to keep your moral purpose in a state of conformity with nature, and, at the same time, to keep externals; but the man who devotes his attention to one of these two things must inevitably neglect the other.

Some people view philosophies such as Stoicism as a way of achieving external success at work, etc. Epictetus, though, advises his students that if they’re really committed to philosophy and the pursuit of wisdom, they’ll probably need to sacrifice some external things. They may need to accept the fact that other people will look down on them for that and think they’re just plain idiots.

April 24, 2024

Special Event: Live from Athens

I will be presenting at a special virtual event on Friday 26th April, to commemorate the birthday of Marcus Aurelius, hosted by Phil Yanov as part of the Conversations with Modern Stoicism series. Marcus Aurelius: Live from Athens: How Stoicism can Save Western Democracy. This will be a one hour session with an intro, presentation, Q&A, breakout sessions, and open conversation with audience Q&A. See the event listing for the time (in your time zone) and other details.

I’ll be drawing on material from my books about Marcus Aurelius, including the newly-released biography Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor. Everyone is welcome; please come along and join the conversation!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 23, 2024

Exclusive Excerpt from "How to Think Like Socrates"

But men of faint heart never yet set up a trophy… wherefore you must go forward to your discoursing manfully, and, invoking the aid of Apollo and the Muses, exhibit and celebrate the virtues of your ancient citizens. —Plato, Critias, 108c

[How to Think Like Socrates is now available for preorder in hardback, ebook, and audiobook formats from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other bookstores. Order now and be one of the first to receive a copy!]

The year is 79 BCE. Three centuries have passed since the death of Socrates. A distinguished traveler from Rome, the statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero, is visiting the Athenian Academy for an afternoon stroll with his friends. The school founded here by Plato, Socrates’s most famous student, is the most important philosophical institute in history—every subsequent academy bears its name. For centuries young men had flocked here to hang on the words of great orators and philosophers as they paced up and down brightly painted marble colonnades while athletes trained nearby, wrestling and running on the tracks. When Cicero and his companions arrive, however, they find the grounds eerily silent and completely deserted.

As they walk along the vacant pathways, nevertheless, the friends feel a profound connection to the past, stronger than any text could convey. The nearby garden of Plato’s house, one says, seems, very vividly, “to bring the actual man before my eyes.”

We should feel inspired not only to know about the great sages of history, in a purely intellectual way… but also to emulate their way of living.

Cicero feels that such places, where great philosophers once explored the nature of wisdom, actually miss the sound of their voices. He imagines the Academy itself mourning the loss. The companions agree that the form of nostalgia they are experiencing can be a healthy sentiment, if it encourages them to follow the example set by men like Plato and Socrates. We should feel inspired not only to know about the great sages of history, in a purely intellectual way, says Cicero, but also to emulate their way of living.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Just seven years prior, the Academy area, which lay outside the city walls, had been occupied and despoiled by Roman legionaries during the dictator Sulla’s brutal siege of Athens. Its sacred groves were felled to provide timber for war machines, and its shrines and libraries were looted. The Academy may, therefore, have appeared semi-derelict to Cicero and his friends. Despite the damage inflicted by Sulla, philosophical studies continued at Athens for several centuries, but the city never recovered its former glory.

Since the end of the classical period, the study of philosophy has shifted from being a practical way of life to being a largely bookish and theoretical pursuit. This change has been lamented by many, such as the British philhellene Lord Byron, who mourned the decline of Athens, and the fading memory of Socrates, the quintessential Athenian philosopher.

As Byron reminisced about watching the Mediterranean sun disappear behind the mountains, he exclaimed:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedOn such an eve his palest beam he castWhen, Athens! here thy Wisest looked his last.How watched thy better sons his farewell ray,That closed their murdered Sage’s latest day!Socrates was, of course, executed not literally “murdered” by his fellow citizens – Byron’s language is meant to express a sense of terrible injustice and loss. Yet despite Socrates’ reputation as one of history’s greatest sages, his teachings and the remarkable stories of his life, with which they were entwined, remain unfamiliar to the majority of people. The Socratic dialogues are seldom read today, except by a handful of classical scholars. And Plato’s Academy, the cradle of Western philosophy, has lain in ruins for well over a thousand years—but it does still exist.

Preorder your copy today to read more from How to Think Like Socrates…

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

What other authors have said…This is an intriguing and original book, as well as being engagingly written and highly accessible. It is innovative both in linking the Socratic dialogues, especially those of Plato, with their historical context and in highlighting the significance of Socratic philosophical enquiry for modern readers. The connection made between Socratic method and CBT psychotherapeutic guidance is particularly suggestive. — Christopher Gill, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Thought, Exeter University, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance

Donald Robertson creates a wonderful semi-fictionalized Socrates to introduce modern readers to the birth of philosophy in Athens. We experience first-hand the method Socrates made famous — of subjecting our deepest beliefs to a cross-examination that jolts and stings like an electric ray. In our modern world that swirls with disinformation and unreason, we need nothing less to awaken us from our illusions. — Nancy Sherman, Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, and author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! Wisdom isn’t a rulebook but a mindset. It develops from a life of honest and courageous inquiry. Donald Robertson masterfully and vividly takes us back to the Athens of Socrates and recreates the setting as well as he does the powerful ideas that one place, time, and person launched into the world forever. It’s an introduction to philosophy as a way of life that’s as gripping as any novel, and is as novel as a philosophy book can be. Highly recommended! — Tom Morris, author of Philosophy for Dummies and Stoicism for Dummies

April 17, 2024

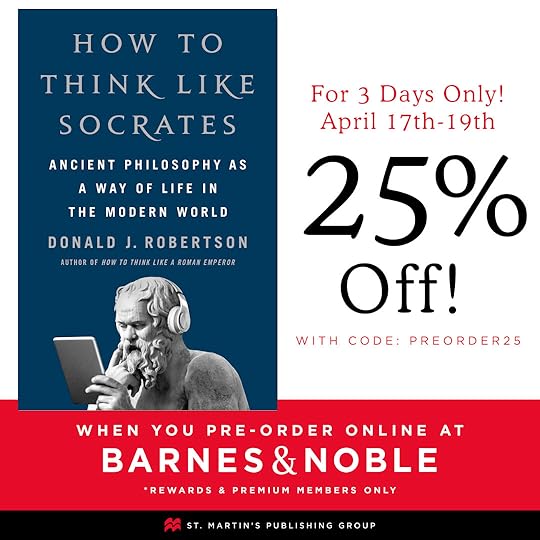

Announcing How to Think Like Socrates

Well, this is no ordinary book, and so it took a long time to finish, but it’s finally here… I am delighted to officially announce that my new book How to Think Like Socrates, published by St Martin’s Press, is now available for preorder!

Usually it takes about a year to write a book like this but How to Think Like Socrates took more like a year and a half. It’s a similar concept to How to Think Like a Roman Emperor — a combination of ancient biography, philosophy, and modern psychology woven together — but I would say that roughly four times as much work went into the new book. Check out the special offer below, which Barnes and Noble have generously agreed to, in celebration of the cover reveal. Scroll down to read some early endorsements from other authors, and a brief explanation of the unique approach adopted in writing How to Think Like Socrates.

Preorder it in any format (hardback, ebook, or audiobook) at Barnes & Noble before 19th April and get 25% off with code PREORDER25. Note: this discount is only available to B&N members but free memberships are available. Already a member? Preorder your copy now from Barnes & Noble.

If this discount doesn’t apply in your region, don’t worry — other special offers will be available in the future. You’ll also find the book listed on Amazon and on many other retailers — learn more on the website of Macmillan, the publisher.

This is no ordinary book so I hope that people enjoy it and I’m relieved that the feedback so far from authors that I respect has, as you will see below, been very positive.

One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! — Tom Morris

What other Authors SaidThis is an intriguing and original book, as well as being engagingly written and highly accessible. It is innovative both in linking the Socratic dialogues, especially those of Plato, with their historical context and in highlighting the significance of Socratic philosophical enquiry for modern readers. The connection made between Socratic method and CBT psychotherapeutic guidance is particularly suggestive. — Christopher Gill, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Thought, Exeter University, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance

Donald Robertson creates a wonderful semi-fictionalized Socrates to introduce modern readers to the birth of philosophy in Athens. We experience first-hand the method Socrates made famous — of subjecting our deepest beliefs to a cross-examination that jolts and stings like an electric ray. In our modern world that swirls with disinformation and unreason, we need nothing less to awaken us from our illusions. — Nancy Sherman, Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, and author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

One of the best books ever written on the power and practicality of philosophy for a good and successful life! Wisdom isn’t a rulebook but a mindset. It develops from a life of honest and courageous inquiry. Donald Robertson masterfully and vividly takes us back to the Athens of Socrates and recreates the setting as well as he does the powerful ideas that one place, time, and person launched into the world forever. It’s an introduction to philosophy as a way of life that’s as gripping as any novel, and is as novel as a philosophy book can be. Highly recommended! — Tom Morris, author of Philosophy for Dummies and Stoicism for Dummies

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

How I Wrote this BookAlthough I’ve written three books in a row about Marcus Aurelius, when people ask if he’s my favorite philosopher, I usually reply that, in fact, he’s my second favorite. Socrates has always been my favorite philosopher. So it seemed obvious to me that I should follow-up the success of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor by writing a similar kind of book about Socrates.

There were some big challenges, though. Socrates lived over five centuries before Marcus Aurelius, and our information about his life is notoriously incomplete and unreliable. The Stoics often expressed their philosophy in short maxims and simple principles, but Socrates was known for asking questions and engaging in intricate, sometimes quite lengthy, dialogues, in which his philosophical intentions are seldom made entirely explicit. Worse, although Marcus engaged in several notable wars, the story of the period in which he lived is relatively straightforward. By contrast, Socrates lived through the notoriously complex Peloponnesian War, which spanned 27 years, and involved many Greek states, most notably the birthplace of Socrates, Athens, whose political in-fighting can be quite baffling at times to modern readers.

Early on in the project, I had to make a difficult decision. The source materials with which we have to work when telling the story of Socrates, such as the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon, and the later anecdotes about him, are generally taken to be semi-fictional in nature. Rather than attempting to write an academic biography, which would probably be unreadable for most non-academics, I decided to adopt a narrative style and embrace the literary character of Socrates — building upon the stories about him handed down to us in ancient sources. I simplified dialogues, combined character, added sections for clarification, and basically approached the project as if I were writing a movie script that aimed to tell the story of Socrates, in a way that captures the spirit of his character and the core of his philosophy. My overriding concern at all times was to make the life and thought of Socrates more accessible to modern readers.

I combined elements from Plato, Xenophon, and other ancient sources, in order to reconstruct the story we’re told about Socrates’ life, in a way that I could both dramatize and connect with the substance and method of his philosophy. Not only that, but I set out to make links apparent with modern psychology! Although I have degrees in philosophy, and, in fact, that’s where I started out, I am a clinician by profession, not an academic — I’m a psychotherapist, first and foremost, rather than a philosopher, historian, or classicist. To my mind, that’s an advantage in one key sense — the psychological implications of Socratic thought always stood out to me quite clearly, in ways that I felt were often completely overlooked by academics.

Socrates, as much as the Stoics, is the ancient forerunner of modern cognitive psychotherapy — and yet very little has been written about his approach to psychotherapy, although it is sometimes quite explicitly stated in the Socratic dialogues. I wanted to highlight the psychological implications of Socratic philosophy, in relation to the self-improvement concerns shared by modern readers, which were just as important to philosophy students in ancient Athens.

This is the book about Socrates that I wish I had read as a teenager, before I read anything else on philosophy.

I undertook what, at first, seemed like an almost impossible task, because I told myself that if I even made it 1% of the way toward achieving my goal, it would be worthwhile. I wrote a book about Socrates that I felt would be of benefit to the sort of people who came to me for help with problems such as anxiety and depression. Moreover, this, in a nutshell, is the book about Socrates that I wish I had read as a teenager, before I read anything else about philosophy.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 11, 2024

Stoicism and the Eleusinian Mysteries

For I made a vow, when the war began to blaze highest, that I too would be initiated... —Marcus Aurelius, quoted in Lives of the Sophists

Photo taken by the author, Donald Robertson, showing the bust of Marcus Aurelius at Elefsina.

Photo taken by the author, Donald Robertson, showing the bust of Marcus Aurelius at Elefsina.The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 AD) is best-known today as the author of The Meditations, a collection of personal reflections on ethics and self-improvement inspired by Stoic philosophy. While researching my recent book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, I visited several locations associated with key events in his life. One was Carnuntum, in Austria, the legionary fortress where he stationed himself while fighting the Marcomannic War, and where part of The Meditations was written. Another was the Greek town of Elefsina, just outside Athens, which was known in antiquity as Eleusis, the home of the famous Eleusinian mystery religion, based upon the myth and rites of the goddess Demeter. Marcus became a patron of Eleusis and was initiated there toward the end of his life.

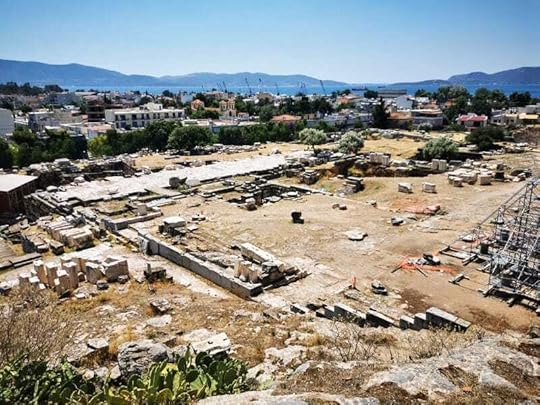

The archeological site of Eleusis. Photo by the author.

The archeological site of Eleusis. Photo by the author.You can still see a bust of Marcus Aurelius in the extensive archeological site which contains the ruins of the ancient Temple of Demeter. Marcus is quite well-preserved, although his head has either broken off recently or been removed for repairs. This bust adorned the pediment (the top section) of the Greater Propylaea, a monumental gate at the entrance to a large fortified complex containing the temple of the Eleusinian mysteries. This gate was apparently part of a rebuilding project undertaken after the temple was sacked by a Sarmatian tribe called the Costoboci, around 170 AD. They rode all the way from their homeland, north of Roman Dacia (i.e., somewhere in the area of modern-day Ukraine), down through the Balkans, and finally besieged the temple and looted its treasures, before being driven back by the Roman army.

Following the sack of Eleusis, Marcus had the telesterion (initiation hall) completely rebuilt, and in 176 AD he visited Athens in person to be initiated.

Marcus was very interested in religion. We know this from his private correspondence and various details provided in the Roman histories. His father’s side of the family even claimed to be descendants of King Numa, who, according to legend, founded the ancient priestly colleges and rites of the Roman religion. As emperor, Marcus served as pontifex maximus, or high priest, and took his duties in this regard very seriously. Following the sack of Eleusis, he had the telesterion (initiation hall) completely rebuilt, and in 176 AD he visited Athens in person to be initiated.

The mystery religions were sworn to secrecy. That makes them very frustrating for historians because while we know they were very influential, we know very little about their doctrines or rituals. Marcus had probably already been initiated into the Cult of Mithras, while commanding the legions in Carnuntum, near modern-day Vienna in Austria, during the First Marcomannic War. Mithraism was very popular with Roman soldiers and many temples to Mithras, or mithraeums, have been unearthed at Carnuntum. There happens also to have been a mithraeum at Eleusis, alongside the main temple, which was dedicated to the goddess Demeter. However, in this article we’ll focus on the Eleusinian Mysteries and their relationship with the writings and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

Sheaves of corn and poppy flower at Eleusis. Photo by the author, Donald Robertson.The Worship of Demeter

Sheaves of corn and poppy flower at Eleusis. Photo by the author, Donald Robertson.The Worship of DemeterDemeter was the Olympian Greek goddess of the harvest, responsible for the art of agriculture. She was sometimes called simply the goddess of grain. She was also associated with fertility, and to some extent with nature in general. Her worship at Eleusis was part of a very ancient tradition, bound up with her myths and with the symbolism of growing and harvesting crops.

Photo by Leonhard Niederwimmer on Unsplash

Photo by Leonhard Niederwimmer on UnsplashThe site at Eleusis still contains archeological remains depicting poppy flowers and corn (wheat or barley) sheaves, two of the main symbols of Demeter. Poppy flowers, which like to grow in wheat and barley fields, also adorned the pediment containing the bust of Marcus Aurelius. He had linked his own image, in stone, with the symbolism of the goddess.

More generally, Demeter is associated with agriculture and the harvesting of cereals, fruits, and other crops. For instance, when Demeter was in distress, the Attic king Phytalus showed her kindness and hospitality. In return she taught him how to cultivate fig trees. As we’ll see, there are several quite striking references to ears of corn and fig trees in Stoic writings, which employ symbolism quite reminiscent of the mysteries of Demeter.

The Abduction of PersephoneThe latter part of the word Demeter happens to mean “mother” in Greek (meter). There’s some debate as to whether the first part (de) originally meant “earth” or “grain” — she could be either named earth-mother or grain-mother. We happen to have a book titled The Compendium of Greek Theology by a Stoic called Cornutus, which links Demeter with Hestia, goddess of the hearth, and states bluntly “both seem to be none other than the earth.”

Since it gives birth to everything and nourishes it like a mother, the ancients called it ‘De-meter’, as if it were Earth-Mother; or else ‘mother Deo’ because the earth and the things on it ungrudgingly produce what men can divide among themselves and feast on; or because on it they meet with, i.e. find, what they seek. — Cornutus, Compendium of Greek Theology

Whatever its origins, though, the name Demeter was bound to evoke the notion of motherhood. Indeed, Demeter had a beloved daughter called Persephone, sometimes known as Kore, meaning a young girl, virgin, or maiden. One day as she was picking flowers, she was abducted by the god Hades. He took her to his dark underground kingdom where she was forced to become his unwilling queen. Demeter was distraught at the mysterious disappearance of her daughter, and travelled the earth searching for her in vain. In other words, the Eleusinian mysteries were based around tragic and highly emotive symbolism — the abduction and rape of a child. Perhaps we would even describe this as a story about “sex trafficking” today.

Photo by Mateus Campos Felipe on Unsplash

Photo by Mateus Campos Felipe on UnsplashWhile Demeter wept, the earth became barren, and there was much suffering. Eventually, Zeus took pity on her, and arranged for Persephone to return to the world of the living. However, Hades had tricked her into eating six pomegranate seeds, for each of which she was fated to spend one month every year living with him in the Underworld.

Cornutus, says explicilty that the disappearance of Persephone symbolizes the planting of seeds.

There is a myth that Hades kidnapped the daughter of Demeter, because of the disappearance of the seeds under the earth for a certain time. — Cornutus, Compendium of Greek Theology

The fruits and grains of the harvest, sacred to Demeter, are provided by her, by Nature, only in due season, for part of the year. Persephone was likewise only with her mother for part of each year, symbolizing the cycles of nature, and the transience of all worldly things, even our loved ones. It’s a myth, in part, about coming to terms with loss, and impermanence.

The Rites of EleusisEvery year, the rites would begin with thousands of initiates gathering to listen to a proclamation from the hierophant of Demeter at the Stoa Poikile, in the Athenian agora. This was, of course, the location where the Stoic school was founded and after which it was named. Five days of celebrations and ritual preparations followed, culminating with a torchlit procession along the Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis. The ceremonies continued there for another four days during which time initiations were carried out.

For among the many excellent and indeed divine institutions which your Athens has brought forth and contributed to human life, none, in my opinion, is better than those mysteries. For by their means we have been brought out of our barbarous and savage mode of life and educated and refined to a state of civilization; and as the rites are called ‘initiations,’ so in very truth we have learned from them the beginnings of life, and have gained the power not only to live happily, but also to die with a better hope. — Cicero

The nature of these initiations was highly secret. We know they consisted of things said (logomena), things enacted (dromena) and things seen (deiknymena). It’s likely that dramatic scenes from the myth of Demeter and Persephone were acted out in theatrical performances — perhaps the actors even felt themselves to be representing the goddesses spiritually. In any case, the initiation must have been a highly-emotive experience. It was said to culminate in the epopteia or mystical vision — literally, “the seeing”.

Initiates drank a concoction known as the kykeon (“mixture”), which was perhaps a type of barley-water flavoured with mint leaves. However, some researchers now believe that it also contained powerful psychotropics. This was potentially due to the deliberate cultivation and processing of ergot, a hallucinogenic fungus that grows naturally on barley and other crops. This experience left initiates feeling somewhat less afraid of dying — to “die with better hope” as Cicero cryptically puts it. Perhaps they felt they had expanded their consciousness and glimpsed a vision of the afterlife.

Marcus in EleusisAlthough Marcus was devoted to Stoicism, a philosophy founded in Athens, he had never actually been there, as far as we know, until a hiatus in the Marcomannic Wars allowed him to tour the east in 176 AD. There are many references to the fact he was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries while at Athens. This was clearly a well-known fact and probably considered one of the most significant events of his reign.

After he [Marcus Aurelius] had settled affairs in the East he came to Athens, and had himself initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries in order to prove that he was innocent of any wrongdoing, and he entered the sanctuary unattended. — Historia Augusta

While Marcus was there he set up funding for several chairs in philosophy and rhetoric at Athens.

When Marcus had come to Athens and had been initiated into the Mysteries, he not only bestowed honours upon the Athenians, but also, for the benefit of the whole world, he established teachers at Athens in every branch of knowledge, granting these teachers an annual salary. — Cassius Dio

Another historian, Philostratus, quotes from a purported letter of Marcus Aurelius in which he asks the famous Sophist Herodes Atticus, his old Greek rhetoric tutor, to officiate at his initiation in Eleusis.

[Marcus wrote to Herodes Atticus:] demand reparation from me in the temple of Athena in your city at the time of the Mysteries. For I made a vow, when the war began to blaze highest, that I too would be initiated, and I could wish that you yourself should initiate me into those rites. — Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists

Marcus may have meant the famous Temple of Athena Parthenos, known as the Parthenon, on the Acropolis, in the centre of Athens.

The process of being initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries actually took several days and began in Athens. After some initial rites there was a procession from the Sacred Gate of the Kerameikos, or cemetery, in Athens, to nearby Eleusis. The Sacred Way, as the road from Athens to Eleusis was known, measured 22km, and could probably be walked in about four or five hours. It’s notable that the procession began among the tombs of the Kerameikos as much of the symbolism relates to Hades and the concept of an afterlife, but also to the notion of coming to terms with our own mortality.

We can certainly take note of several parallels between the Stoic ideas expressed by Marcus and the imagery of the Eleusinian mysteries.

If Marcus vowed during the height of the First Marcomannic War that he would be initiated, that almost certainly means he made this promise while he was in the middle of writing The Meditations. We cannot know whether passages in The Meditations were influenced by teachings from Eleusis or not. However, we can certainly take note of several parallels between the Stoic ideas expressed by Marcus and the symbolism of the Eleusinian mysteries.

The Mysteries in The MeditationsMajor themes found in the Stoicism of The Meditations clearly resonate with the myth of Demeter, such as coping with loss, accepting mortality, and viewing these things as processes of universal nature. For example, the following passage quotes a lost tragedy of Euripides, and could hardly sound more Eleusinian:

Life must be reaped like the ripe ears of corn. One man is born; another dies. — Meditations, 7.40

Marcus obviously loved this line because he quotes it again later in The Meditations (11.6). He clearly means that we should accept death as a natural process, like the reaping of corn that is growing old. As the plant begins to die, it sheds seeds, which are sown in order to grow new crops.

Elsewhere, Marcus quotes a notorious passage from the Discourses of Epictetus (3.24), which once again uses the reaping of corn as a metaphor for accepting mortality:

When a man kisses his child, said Epictetus, he should whisper to himself, “Tomorrow perhaps you will die.” — But those are words of bad omen. — “No word is a word of bad omen,” said Epictetus, “which expresses any work of nature; or if it is so, it is also a word of bad omen to speak of the ears of corn being reaped”. — Meditations, 11.34

He also quotes Epictetus (3.24) employing the metaphor of looking for figs out of season.

To look for the fig in winter is the act of a madman and such is he who looks for his child when it is no longer allowed. — Meditations, 11.33

The fig-tree was another symbol of Demeter, as we’ve seen. The loss of Persephone was strongly associated with the symbolism of crops being out of season and denied to us. At first, Demeter grieved terribly, and searched frantically for her child. Although Persephone was eventually returned, it was only temporary. Her mother was forced to accept recurring periods during which her child was absent, and to view this as part of the natural order. How could an ancient Greek or Roman have talked about looking for a child when it is no longer allowed without recalling the myth of Persephone?

The Stoic Cornutus, who had claimed that Demeter was “none other than the earth”, goes on to say:

Mythology tells that she is first and last because the things that were born from the earth and sustained by it are dissolved into it; and this is also why the Greeks start and end their sacrifices with her. — Cornutus, Compendium of Greek Theology

Marcus uses similar language and literally describes death as a mystery (mysterion) of nature — a phrase which perhaps sounds like an allusion to the mysteries of Demeter, the earth-mother and goddess of nature.

Death is such as generation is, a mystery of nature; composition out of the same elements, and a decomposition into the same; and altogether not a thing of which any man should be ashamed, for it is not contrary to [the nature of] a reasonable animal, and not contrary to the reason of our constitution. — Meditations, 4.5

By contrast, those who refuse to accept loss as part of nature remind Marcus of the sacrificial piglets who screech and wriggle beneath the blade. (A cruel image by modern standards but one that to which many ancient Greeks and Romans would be desensitised.)

Imagine every man who is grieved at anything or discontented to be like a pig which is sacrificed and kicks and screams. Like this pig also is he who on his bed in silence laments the bonds in which we are held. And consider that only to the rational animal is it given to follow voluntarily what happens but simply to follow is a necessity imposed on all. — Meditations, 10.28

The Greeks often sacrificed animals such as cattle and sheep. The sacrifice of piglets was not unusual but was, as it happens, particularly associated with the worship of Demeter and Persephone. Indeed, as we’ve already seen, worshippers would sacrifice piglets to these goddesses in exchange for the chance to be initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. The psychodrama that followed was intended to cleanse them of their own fear of death, i.e., they all hoped to become unlike the sacrificial piglets.

The church father Hippolytus reported that after being initiated, celebrants would chant “Rain! Conceive!” (hye kye!). These words seemingly addressed the sky and earth respectively, and were a plea for crops to grow, especially fields of wheat and barley. This obviously resembles another Athenian rainmaking prayer admired by Marcus in The Meditations for its simplicity:

A prayer of the Athenians: “Rain, rain, O dear Zeus, down on the ploughed fields of the Athenians and on the plains.” In truth we ought not to pray at all, or we ought to pray in this simple and noble fashion. — Meditations, 5.7

Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics, mentions that “Euripides says that when the earth is parched it loves rain, and the sublime heaven, when full of rain, loves to fall to earth.” Marcus seems to quote the same line from this lost tragedy of Euripides, which echoes the symbolism of the chant “Rain! Conceive!” once again:

“The earth loves the rain;” and “the solemn heaven is moved by love;” and the universe loves to make whatever is about to be. I say then to the universe, that I love as you love. And is not this too said that “this or that loves to be produced?" — Meditations, 10.21

Once more, a simple agrarian metaphor is used to express a spiritual or philosophical concept. In this case, the earth “loving” to receive the rain, in accord with nature, symbolizes the Stoic love of one’s fate (amor fati).

As noted above, we have no idea whether Marcus would have said these ideas were derived from the Eleusinian mysteries. However, as he was writing The Meditations, we know he vowed that one day, as soon as the war was over, he would go to Athens. That means he had long intended to stand before the Stoa Poikile in order to listen to the pronouncement of the hierophant, along with thousands of other worshippers. He would ritually bathe and sacrifice a screaming piglet to Demeter and Persephone. He would gather with others among the tombs at the Keramikos and proceed by torchlight along the Sacred Way to be initiated in the Telesterion at Eleusis.

It was with philosophical intent that they began to celebrate the ‘mysteries’ for her, rejoicing at the same time in the discovery of things beneficial for life, and in a festival which they used to bear witness to the fact that they had stopped fighting with each other over the necessities, and were replete, i.e. satiated. — Cornutus, Compendium of Greek Theology

With this end in mind, I feel certain, Marcus realized that his talk of “ears of corn”, “figs in winter”, and “mysteries of nature”, was echoing the famous symbolism of the Eleusinian mysteries.

April 3, 2024

Stoicism at the Athenian Acropolis

The Roman emperor, and Stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius wrote in his personal notes on Stoic philosophy:

A fine reflection from Plato. One who would converse about human beings should look on all things earthly as though from some point far above, upon herds, armies, and agriculture, marriages and divorces, births and deaths, the clamour of law courts, deserted wastes, alien peoples of every kind, festivals, lamentations, and markets [agoras], this intermixture of everything and ordered combination of opposites. — Meditations, 7. 48

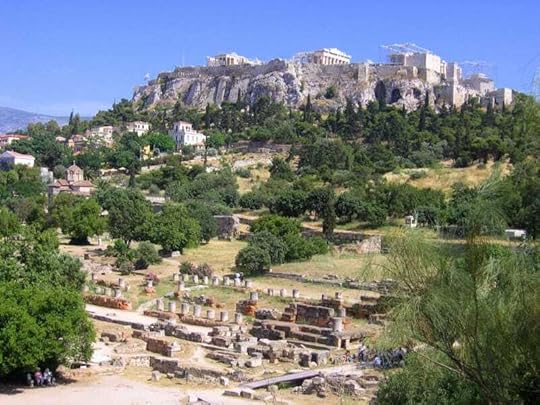

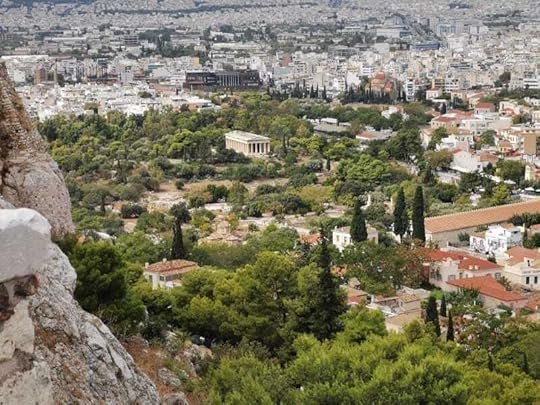

View of the Acropolis from below, overlooking the ancient agora

View of the Acropolis from below, overlooking the ancient agoraThis looks like it’s intended as a quote from Socrates in Plato’s writings but, incidentally, it doesn’t appear in any of the surviving Platonic dialogues.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In this and other passages, it’s clear that Marcus is describing a mental exercise — he tells himself to regularly picture such scenes. The French scholar Pierre Hadot coined the name the “View from Above” for this sort of contemplative practice, which appears in many ancient sources — not only the Stoics.

Sometimes it’s tempting to imagine that what’s being described is like the viewpoint of Zeus, or the other gods, atop Mount Olympus, as they look down on mortal affairs below. Indeed, the practice of trying to expand one’s mind by imagining the perspective of a god was a common contemplative exercise in the ancient world and could take several other forms. However, one day a more obvious analogy dawned on me.

I was reading this passage from The Meditations on the Pnyx hill, wondering whether it truly came from Plato or even Socrates. I looked up for a moment at the Acropolis in front of me and suddenly realized that I could almost be reading a description of the view from the Acropolis, where the ruins of the Parthenon, an ancient temple to Athena is located. The word “Acropolis”, in ancient Greek, literally meant “highest part of the city”. It refers to the hill in the centre of Athens that overlooks the ancient agora, the city centre and marketplace. (Indeed, in the passage above, Marcus uses the word agora, translated “marketplace”.)

There are several other passages in The Meditations that appear to relate to the same contemplative practice. For example:

You should always keep these three thoughts at hand… if you were suddenly raised aloft and looked on human affairs from above in all their diversity, with what contempt [or rather indifference] you would view them, seeing at the same time what a host of beings live all around in the air and the ether, and that however often you were raised aloft, you would behold the same things, ever unvarying, ever as short-lived — and it is in these that you set your pride! — Meditations, 12.24

However, in another well-known passage, Marcus actually employs the word acropolis:

Remember that your ruling centre becomes invincible when it withdraws into itself and rests content with itself, doing nothing other than what it wishes, even where its refusal to act is not reasonably based; and how much more contented it will be, then, when it founds its decision on reason and careful reflection. By virtue of this, an intelligence free from passions is a mighty citadel [acropolis]; for man has no stronghold more secure to which he can retreat to remain unassailable from that time onward. One who has failed to see this is merely ignorant, but one who has seen it and fails to take refuge there is beyond the aid of fortune. — Meditations, 8.48

Typical translations of akropolis as “citadel”, etc., obscure the fact that the original Greek implies a high-up place, akin to the “some point far above” mentioned by Marcus in passage 7.48, quoted earlier .

Combining these passages, therefore, a description emerges of the ideal Stoic mind-set as resembling, in Marcus’ own words, an acropolis, high above, looking down on the hustle and bustle of an agora.

NeostoicismIn the sixteenth century, the Neostoic Justus Lipsius actually told the following story about Solon, one of the “seven sages”, which is set in a high tower, presumably on one of the hills, overlooking Athens, quite possibly the Acropolis.

Solon, seeing a very friend of his at Athens mourning piteously, brought him into a high tower and showed him underneath all the houses in that great city, saying to him “Think with yourself how many sundry mournings in times past have been in all these houses, how many at this present are, and in time to come shall be; and leave off to bewail the miseries of mortal folk, as if they were your own.”

Photo I took of the ancient agora from the Acropolis, after Stoicon 2019 in Athens

Photo I took of the ancient agora from the Acropolis, after Stoicon 2019 in AthensLipsius’ friend advises him to imagine a similarly broad perspective on events, not by literally climbing a hill but by using his imagination to place himself atop Mount Olympus.

I would wish you, Lipsius, to do the like in this wide world. But because you cannot in deed and fact go to, do it a little while in conceit and imagination. Suppose, if it please, that you are with me on the top of that high hill Olympus; behold from there all towns, provinces, and kingdoms of the world, and think that you see even so many enclosures full of human calamities. These are but only theatres and places for the purpose prepared, in which Fortune plays her bloody tragedies.

He is to continually remind himself of the “View from Above” in order to alleviate his distress, but also to remind himself of his own mortality.

Which things think well upon, Lipsius, and by this communication or participation of miseries, lighten your own. And like they [Roman generals] which rode gloriously in triumph, had a servant behind their backs who in the midst of all their triumphant jollity cried out often times “you are a man” [and “remember you must die”], so let this be ever as a prompter by your side, that these things are human, or appertaining to men. For as labour being divided between many is easy, even so likewise is sorrow.

The “View from Above” was a particularly familiar concept to ancient Athenians. This elevated, serene, and somewhat detached perspective on the agora where goods were sold and other important business conducted was the view from the sacred Acropolis in the middle of their city, and from other nearby vantage points on high ground.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

March 25, 2024

How to Eat Like a Stoic

The ancient Cynic and Stoic philosophers were very interested in food. (At the end of this article you’ll even find a modern recipe for Stoic soup.)

They talk both about what we should eat and how we should eat it, if we want to live wisely and gain strength of character. For instance, we’re told of the Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus:

He often talked in a very forceful manner about food, on the grounds that food was not an insignificant topic and that what one eats has significant consequences. In particular, he thought that mastering one’s appetites for food and drink was the beginning of and basis for self-control.

Musonius taught that Stoics should prefer inexpensive foods that are easy to obtain and most nourishing and healthy for a human being to eat. It might seem like common sense to “eat healthy” but the Stoics also thought we potentially waste far too much time shopping for and preparing fancy meals when simple nutritious meals can often be easily prepared from a few readily-available ingredients.

Musonius advises eating plants and grains rather than slaughtered animals. He recommends fruits and vegetables that do not require much cooking, as well as cheese, milk, and honeycombs. The Stoic weren’t strictly vegetarian — unlike their philosophical cousins the Pythagoreans. Some Stoics were probably vegetarian and others not, although they wouldn’t have eaten very much meat in general.

The Early Stoic and Cynic DietZeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school, had for many years been a Cynic philosopher. “Zeno”, we’re told, “thought it best to avoid gourmet food, and he was adamant about this.” He believed that once we get used to eating fancy meals we spoil our appetites and start to crave things that are expensive or difficult to obtain, losing the ability to properly enjoy simple, natural food and drink.

We know more about the Cynic diet because it was simpler and more austere. The Cynics were known, typically, for drinking water (instead of wine), and eating barley-bread and lentil soup or lupin beans — all very cheap ingredients. One Cynic letter says: “It is not only bread and water, and a bed of straw, and a rough cloak, that teach temperance…” We’re told of Crates, the Cynic teacher of Zeno, who abandoned his fortune:

Having adopted simpler ways, he was contented with a rough cloak, and barley-bread, and vegetables, without ever yearning for his former way of life or being unhappy with his present one.

The Stoics were generally more urbane and less extreme than their Cynic predecessors, and their diet seems to have been a bit less restricted. However, right down until the time of the last famous Stoic of antiquity, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, we hear about some Stoics modelling themselves on the Cynic lifestyle, which in turn appears to have been influenced by aspects of the notorious Spartan agoge or training.

For example, in a letter to Marcus Aurelius, we find his rhetoric tutor and family friend, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, joking about how he saw one of the emperor’s little sons clutching a chunk of brown bread, “quite in keeping with a philosopher’s son.” In another letter, we get a glimpse of Marcus’ eating habits:

Then we went to luncheon. What do you think I ate? A wee bit of bread, though I saw others devouring beans, onions, and herrings full of roe.

Eating with Attention and Moderation

Eating with Attention and ModerationMusonius also thought we should train ourselves to avoid gluttony:

Since this behavior [gluttony] is very shameful, the opposite behavior — eating in an orderly and moderate way, and thereby demonstrating self-control — would be very good. Doing this, though, is not easy; it demands much care and training.

Stoics should eat slowly and with mindfulness of their own character and actions, paying attention (prosoche) to their thoughts and actions. They should use reason to judge where the boundary of what’s healthy lies and exercise moderation wisely.

The person who eats more than he should makes a mistake. So does the person who eats in a hurry, the person who is enthralled by gourmet food, the person who favors sweets over nutritious foods, and the person who does not share his food equally with his fellow-diners. […] Since these and other mistakes are connected with food, the person who wishes to be self-controlled must free himself of all of them and be subject to none. One way to become accustomed to this is to practice choosing food not for pleasure but for nourishment, not to please his palate but to strengthen his body.

That very simply means making an effort to eat healthy food. However, for Stoics the main reason for doing this isn’t just to improve our health, paradoxically, it’s to strengthen our character by exercising self-awareness and the virtue of self-discipline. That’s important today because we’re bombarded with contradictory advice about the healthiest way to eat. The Stoics would say that we shouldn’t allow that to confuse us. We should make a reasonable decision and stick to it in order to develop self-control because that’s fundamentally more important than losing weight or becoming physically healthy anyway. To be clear, both goals are of value, but for Stoics the primary goal is strength of character and physical health, while “preferred” as they phrase it, is of secondary importance.

Therefore, the goal of our eating should be staying alive rather than having pleasure — at least if we wish to follow the sound advice of Socrates, who said that many men live to eat, but that he ate to live. No right-thinking person will want to follow the masses and live to eat, as they do, in constant pursuit of gastronomic pleasures.

Many people who follow Stoicism today also employ intermittent fasting. It’s likely that some ancient Stoics did too, I think. Socrates famously said that “hunger is the best relish”, alluding to the irony that we actually enjoy our food more when we’re hungry, and spoil our appetites when we over-indulge. I fast at least once a week, sometimes eating and fasting on alternate days. For lunch I tend to eat dakos, a simple Cretan salad made from barley-bread rusks, perhaps like the ancient Spartans and Cynics used to eat, and a few common ingredients like chopped tomatoes, olives, and feta.

I think Musonius, and the other Stoics, would also approve of the recipe below because it’s very cheap, mainly uses common vegetable ingredients, which are easy to obtain, and it’s also very easy to prepare. You can easily make a large batch and store it in portions to reheat later. It’s unfussy but tasty and nutritious.

Recipe for Stoic SoupIn Meals and Recipes from Ancient Greece, Eugenia Ricotti describes the following recipe called “Zeno’s Lentil Soup”. It’s a modern recipe loosely based upon ancient sources, including remarks attributed to Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoic philosophy, which are found in the Deipnosophistae (or “Dinner Experts”) of Athenaeus of Naucratis.

1 lb. (450g) lentils

8 cups (2 litres) broth

1 large minced leek

1 carrot, 1 stalk of celery, and 1 small onion, all sliced

2 tablespoons vinegar

1 teaspoon honey

olive oil

12 coriander seeds

salt and pepper to taste

She says to rinse the lentils and put them in a pot with the broth to boil. Then reduce heat and simmer for one hour. Then skim the top, add the vegetables, and leave to simmer until cooked, which should be about 30 minutes. She says that if it seems too watery either add cornstarch or pass some of the lentils through a sieve. Finally, add vinegar and honey for flavour.

After pouring into serving bowls, add a good amount of olive oil — she suggests about 2 tablespoons per serving. Finish by sprinkling on the coriander seeds and adding more salt and pepper to taste.

I’ve made this recipe quite a few times myself. I use dried green lentils, which I soak overnight and boil for a few minutes. I use red wine vinegar and often add a couple of garlic cloves and perhaps a few bay leaves, possibly also a little paprika. I’d also usually garnish it with a few fresh coriander leaves and serve with bread. This is a photo of my version…