Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 26

June 2, 2013

What's the Big Idea?

I’m on my way home from a children’s book conference. It’s a long flight, and I’m struck by how abstract my grasp of distance becomes when I’m traveling at 500 miles an hour. I’d probably have to walk (and swim) the 4,000 miles to really appreciate how far I’ll travel over the next few hours.

A casual preoccupation with scale — both spatial and temporal — began even before I became an author. It was my own children’s constant questions about the size of things, however, that focused my interest and led to one of my first books. Biggest, Strongest, Fastest is a book of animal superlatives. As I worked on that book, I was confronted with what would become a recurring issue: the limitations of the printed page when presenting things of large or small size. I used a simple scale reference — the silhouette of a human figure or hand next to an image of an elephant or flea — to help the reader take the true measure of an animal that wouldn’t fit on the page or one too small to see clearly if not enlarged. In another title, Actual Size, I employed life-size illustrations of animals or parts of animals to get the point across. As long as a subject’s size allows for comparison to something as familiar as the human body, these approaches work pretty well. Once something gets too large or small to relate to something familiar that can be experienced directly, it gets trickier. Similar challenges arise when dealing with big numbers or very long or short periods of time.

Of course, problems of expressing and grasping extremes of scale didn’t originate with the picture book. Millions of years of natural selection operating on our human and pre-human ancestors have favored perceptual abilities that respond to things that aid or threaten our survival. Food, mates, and danger, in most cases, ranged from the size of a small insect to the size of an elephant. A distant mountain or approaching storm represented the upper size limit of something in the physical world that could be directly understood. Many things that were larger or farther away, such as the sun or moon, were eventually incorporated into superstition or myth.

Similar limitations exist in the realm of the temporal. We are limited in our ability to intuitively understand periods of time briefer than, say, the blink of an eye or longer than a few human generations. This hasn’t really changed. We may have an intellectual grasp of the interval that passes when light travels from our computer screen to our eyes at 186,000 miles per second or the 65 million years that have passed since an asteroid collision incinerated much of the earth, but I suspect that none of us have anything other than a metaphorical grasp of these spans of time.

For most of our history, these limitations weren’t important (which is why they exist). But much contemporary science is concerned with objects and events that lie far outside our perceptual abilities. The best science writing — for both children and adults — can provide a vivid (if limited) sense of many things that we can’t actually experience. The book, however, is the same medium that was available to daVinci and Newton. On one hand, this speaks to the value and enduring power of the printed page. But also makes me (a dyed-in-the-wool ink-on-paper person) wonder about the possibilities of new media. The to-this-point-underwhelming (to me, at any rate) ebook will no doubt be the 8-track tape player of the near future. As digital media evolves, however, they may make it possible to explain and demonstrate phenomena that are beyond the capability of the traditional book.

I’m keeping my options open.

(After this was posted, a friend sent an interesting link related to scale. It's worth checking out: http://htwins.net/scale2/)

Published on June 02, 2013 21:52

May 30, 2013

A Glimpse at my Process--Beginnings

My recent visit to the Montana prairie got me

thinking about how an author organizes ideas and chooses what to include in a

piece of writing and what can be left out. Any new subject presents so many possibilities, and

possibilities are what writers thrive on.

Each of us has her or his own ways of working through this process of

considering alternatives and then focusing in on some topics while passing over

others—here’s an example of mine.

I already have the main focus for my book, the life

of bison on American Prairie Reserve (APR), a developing project that aims

to protect a parcel of an ecosystem that once spread from north to south across

the middle third of America.

Already, enough land is protected by APR so that the bison and other

wildlife have a significant area to roam.

My book will focus on the life of one bison calf born there and will

have sidebars featuring various aspects of the life of bison and their

habitat. What topics should I

include and what can I pass over?

A 48-page book can only have so many words!

A lone bison bull on the American Prairie Reserve

While I bounce along in a sturdy four-wheeler with my

driver and guide, Dennis Lingohr, my mind scans possible topics as my eyes scan

the landscape. Our vehicle climbs

up a steep slope and heads down the other side, and I know there’s one point

I’ll be sure to make—the prairie is far from being a rolling plain. It is a wrinkled landscape, with hills

and valleys, nooks and crannies, streams and ponds. Some areas seem quite barren, while others are lush with spring

grass.

Dennis explains how this variety of habitats

reflects both the geological history of the area and the human usage of the

land. For example, glaciers

scraped some of the land of its topsoil, while flood irrigation by ranchers

created grassy swaths that provide good forage for the bison. The landscape will play a major role in

my book.

An alert prairie dog checks out the intruders

Penstemon on the prairie

We pass through a prairie dog town—the bison and the

prairie dog are both key ingredients in a healthy prairie ecosystem, so I’ll be

sure to include the prairie dog.

But what about the wildflowers?

They are beautiful and visually appealing, but do they play an important

role in the life of the prairie itself?

Do the bison nibble on them or leave them alone? I’ll need to find out. Then there’s the weather—just this one

day we are experiencing some of its variety. The day starts out with broken clouds and a light

breeze. As we lunch sitting on an

overlook, the sun peeks out, disappears, and comes out again. The storm clouds gather in the

distance, and I get nervous about the possibility of rain, which can make the

roads impassable.

As I ponder my experience, my mind begins to make

lists of possibilities. I remind

myself that the topics I include must spark the interest of young people. Luckily, my book is not a textbook that

has to include certain facts. It’s

a collection of tidbits and stories that, taken together, will introduce this complex ecosystem from the viewpoint of its largest and most powerful

inhabitant, the bison. But before

even one word is written, I must sort and balance, take on and discard, until I

reach a point where I’m confident my book will both inform and inspire.

Now that I’m back home, where the streets are paved

and the landscape is dotted with houses, I think back to my prairie experience

of wildness and openness, lonesome landscape and companionable creatures, and I

look forward to the challenge of organizing and presenting this

quintessentially American animal and its complex habitat to young readers.

thinking about how an author organizes ideas and chooses what to include in a

piece of writing and what can be left out. Any new subject presents so many possibilities, and

possibilities are what writers thrive on.

Each of us has her or his own ways of working through this process of

considering alternatives and then focusing in on some topics while passing over

others—here’s an example of mine.

I already have the main focus for my book, the life

of bison on American Prairie Reserve (APR), a developing project that aims

to protect a parcel of an ecosystem that once spread from north to south across

the middle third of America.

Already, enough land is protected by APR so that the bison and other

wildlife have a significant area to roam.

My book will focus on the life of one bison calf born there and will

have sidebars featuring various aspects of the life of bison and their

habitat. What topics should I

include and what can I pass over?

A 48-page book can only have so many words!

A lone bison bull on the American Prairie Reserve

While I bounce along in a sturdy four-wheeler with my

driver and guide, Dennis Lingohr, my mind scans possible topics as my eyes scan

the landscape. Our vehicle climbs

up a steep slope and heads down the other side, and I know there’s one point

I’ll be sure to make—the prairie is far from being a rolling plain. It is a wrinkled landscape, with hills

and valleys, nooks and crannies, streams and ponds. Some areas seem quite barren, while others are lush with spring

grass.

Dennis explains how this variety of habitats

reflects both the geological history of the area and the human usage of the

land. For example, glaciers

scraped some of the land of its topsoil, while flood irrigation by ranchers

created grassy swaths that provide good forage for the bison. The landscape will play a major role in

my book.

An alert prairie dog checks out the intruders

Penstemon on the prairie

We pass through a prairie dog town—the bison and the

prairie dog are both key ingredients in a healthy prairie ecosystem, so I’ll be

sure to include the prairie dog.

But what about the wildflowers?

They are beautiful and visually appealing, but do they play an important

role in the life of the prairie itself?

Do the bison nibble on them or leave them alone? I’ll need to find out. Then there’s the weather—just this one

day we are experiencing some of its variety. The day starts out with broken clouds and a light

breeze. As we lunch sitting on an

overlook, the sun peeks out, disappears, and comes out again. The storm clouds gather in the

distance, and I get nervous about the possibility of rain, which can make the

roads impassable.

As I ponder my experience, my mind begins to make

lists of possibilities. I remind

myself that the topics I include must spark the interest of young people. Luckily, my book is not a textbook that

has to include certain facts. It’s

a collection of tidbits and stories that, taken together, will introduce this complex ecosystem from the viewpoint of its largest and most powerful

inhabitant, the bison. But before

even one word is written, I must sort and balance, take on and discard, until I

reach a point where I’m confident my book will both inform and inspire.

Now that I’m back home, where the streets are paved

and the landscape is dotted with houses, I think back to my prairie experience

of wildness and openness, lonesome landscape and companionable creatures, and I

look forward to the challenge of organizing and presenting this

quintessentially American animal and its complex habitat to young readers.

Published on May 30, 2013 22:00

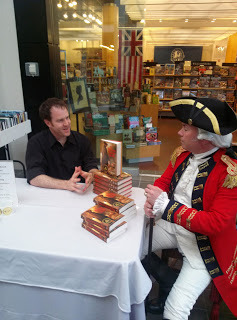

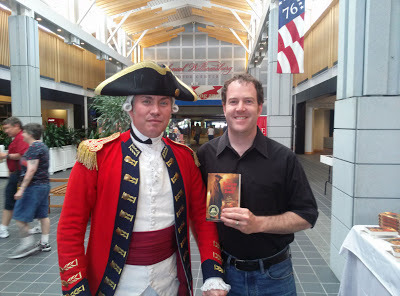

An Hour with Benedict Arnold

About a week ago, in Williamsburg, Virginia, I the great

pleasure of spending an hour with Benedict Arnold. Allow me to explain.

I was sitting outside the bookstore in the Colonial

Williamsburg visitor’s center. This isn’t the ye olde part of Colonial Williamsburg,

this is more like a little shopping mall, with gift stores, a theater, ticket

counters, etc. So I’m sitting there at a table surrounded by tall stacks of my

Benedict Arnold book, and sweaty tourists keep walking by without stopping, and

I’m starting to feel that unique book signing version of lonely desperation.

And then Benedict Arnold strides up. I mean, he was

seriously striding.

I’d heard a rumor that the actor who plays Arnold on the

streets of Colonial Williamsburg might stop by, and here he was. He had the

tricorn hat, the white wig, the heavy red coat of a British officer (this was

the post-treason Arnold). He even walked with a cane and limp, as Arnold did

after being wounded in battle at Saratoga.

“How do you do, sir?” he boomed.

I said something like, “Good. I mean, very well, general.” I

gestured to the piles of books. “I wrote a book about, well… about you.”

“Yes, I’ve read it,” he said, picking up a copy.

I worried he might be offended by the title, The Notorious Benedict Arnold, but it

didn’t seem to bother him. To my surprise, he sat down next to me. I smiled,

but didn’t know what to say. My first thought was to tell I was a big fan of

his. But do I mention my disapproval of the whole betraying your country for

money thing?

A family walked by, slowing to look at us. A writer and a

Redcoat at a folding table.

“Good day to you all!” Arnold called.

The dad stepped to the table. He looked back and forth from

the cover of my Arnold book to Arnold. Then he said, “Could we get a picture

with you?” He meant Arnold. Arnold stood and the kids posed with him and the

dad took a picture on his phone.

Then Arnold sat back down, shook my hand, and introduced

himself as Scott.

That’s when things got really fun. Turns out this guy is

perhaps more obsessed with Benedict Arnold than I am, and knows even more. And

he loves his job, says it’s the best gig in Williamsburg, because he’s such a

controversial figure, and because he gets to ride around on a horse and

harangue Americans.

Think of the dedication. I mean, we nonfiction writers spend

a year or two trying to get into the heads of historical figures. But then we

move on. He never does. He stays inside Arnold. Sometimes, when he’s in a

hurry, he drives home dressed as Arnold. He’s even gotten gas as Arnold (yes,

there were strange looks given).

For about an hour, we swapped theories on obscure points in

For about an hour, we swapped theories on obscure points inArnold’s story. I forgot all about trying to sell books, and was actually

annoyed when people stopped by to talk (usually with him) or take pictures

(always with him). When this happened, he snapped back into character and

traded greetings, and sometimes witty insults, with the visitors. I just sat

there, impressed and inspired. Here’s someone as skilled as any writer at

making history engaging and memorable. And there’s no technology in sight—just the

good old fashioned building blocks of story and character.

Some people enjoyed taunting Arnold, asking if he had any

regrets, if he wished he hadn’t betrayed his country, stuff like that. But he

had quick comebacks at the ready. The only thing that seemed to bother him was

when a group of kids came up, giggling, waving plastic muskets, and asked, “Are

you supposed to be George Washington?”

“No,” he said, frowning, recalling a painful scene. “I was

once… an associate of his.”

The kids stopped laughing. They wanted to hear the story.

Published on May 30, 2013 04:34

May 28, 2013

The Power of Non-Fiction

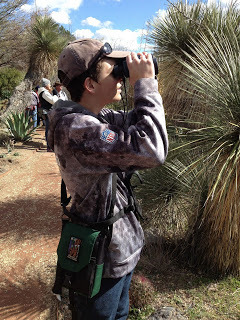

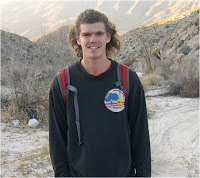

Alex Grant, the

young man pictured here, is the subject of this post. Before I get to him, I

wish to make an announcement that is tangentially, but delightfully, related.

The power of non-fiction, and the myriad ways that

educators, authors and other creative people can harness it, will be the

subject of The 21st Century Children’s Nonfiction Conference, to be

held on June 14-16 at SUNY New Paltz, about 80 miles north of New York City.

Among many stellar speakers are INK’s own Vicki Cobb and Melissa Stewart, along

with Kent Brown of the Highlights Foundation, Robin Terry of National

Geographic Children’s Publishing and other luminaries. The conference

includes 23 workshops, three intensives, two panels, six meals and unlimited

networking opportunities. Details at http://www.childrensNFconference.com;

further information from organizer Sally Isaacs, sisaacs@starconsultinginc.com.

Now about Alex. We met early on a chilly February morning on

a footbridge in the Boyce Thompson Arboretum, 60 mile east of Phoenix. We were among

a dozen or so birding enthusiasts who had gathered for the weekly guided bird walk

sponsored by the Arboretum. Alex and I discussed two related birds, initially indistinguishable to my eyes. Both were wrens, small songbirds with barred tails and thin bills. Binoculars

lifted, Alex pointed out the differences: the canyon wren had more distinct

coloration — reddish brown wings and back, and a bright white throat, compared with the paler, grayish brown

rock wren whose throat lacked the lustrous white. Alex spoke

eagerly, with the facts at his command and a confidence that belied his age: 15. Very soon he might be leading walks like this, as his reputation had reached the Arboretum

and a ranger had invited him to become a volunteer bird guide

— the Arboretum's youngest by far. He and his parents had come on this walk while he considered the offer.

Rock Wren

Canyon Wren

Later, as the sun finally warmed the air enough

for us to shed an outer layer or two, I asked Alex’s mother, Sonja Grant, about her

son’s zeal for birds. It had begun during the summer between first and

second grade. The catalyst was a book called Birds of the World. Alex had checked it out of the library and it had changed his life. True, he had already shown a keen interest in nature, and he'd owned books about birds as well as sharks, insects and other taxa. He’d read some of

them so many times that their pages had fallen out. But with its dazzling photos

and engaging text, Birds of the World

had taken Alex to a new level of interest that he calls “a deep passion.” Before

long, the passion spread to both of his parents, and the family had a new hobby.

School vacations became extended birding outings in Arizona, California, Texas and

Maine, the trips oriented around an important statistic—the number of species seen

between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31 of the year. That number had reached 306 in 2012. Birders refer to a year in which they keep count as "a big year"; the Grants decided to do another big year in 2013, and by mid-May their list was up to 263 species.

Finishing his freshman year at Gilbert High School in Gilbert, AZ, Alex is homing in on a

college education and career in ornithology. And it all started with a non-fiction book.

I am reminded of a quote I once saw from a Jo Carr (if you

know who she is, please let me know): “You can almost divide

non-fiction into two categories: non-fiction that stuffs in facts, as if

children were vases to be filled, and non-fiction that ignites the imagination,

as if children were indeed fires to be lit.” I don’t know anything about the

book that turned Alex into a bird lover (a fair number of books bear the title Birds of the World). It may even fall in

the “stuffs in fact” genus in Jo Carr’s taxonomy but clearly it ignited Alex

Grant’s imagination and illuminated the apparent direction of his life.

Many modalities of non-fiction (in the form of books and other media) will be explored at the New

Paltz conference. Perhaps the one you teach or create will ignite a child’s

life, or your own.

Published on May 28, 2013 01:00

May 24, 2013

When Writers Take Vacations

Finally, the day has come ~ May 24th. Right now, as you are reading this, the Lewis family is embarking on our European vacation. Last month when I saw the INK post schedule for May, I chuckled when I read that my post day was the day we were leaving. Right now, I really have nothing profound to say about nonfiction books and the writing process. My brain is preoccupied with the trip and has been for a few days. So, I’m going to share my thoughts about the trip and writing fiction and nonfiction.

Four years ago when our daughter was looking at colleges, the term semester abroad was of great interest to the entire family. There was no question that our daughter would be studying in a foreign country. We were excited about the idea that after my daughter’s semester abroad, we would be traveling to wherever she was studying to “pick her up”. Fortunately, her semester abroad was spent at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich UK, where she was able to take some great publishing and English Lit classes. And, an amazing three-week spring break romp around Europe, may I add?

Last time we were in London, I was pregnant with my daughter, who turned 21 this week. In other words, it’s been a long while. We went for the London Toy Show, in February. I can only hope the weather is going to be a little better than last time. Our apartment is on the Thames River, feet from where the Mayflower sailed. I’m mentioning all this for several reasons. First, I have nothing but the trip on my brain. Second, my writer self is so excited at the thought of being in the midst of all that history.

After a week in London with side trips to Cornwall, Oxford and possibly Dover, we head to Paris; which I think a certain husband promised me about 20 years ago.

Things are free and clear on the work front. With one publisher, I just signed the release forms, so that book is now off to the printer. With another publisher, I just completed the edits with my project editor, after two rounds of edits with my editor. Women of Steel and Stone is now off to the copy editor. And, hopefully, a new book proposal will make magic at an acquisition meeting, while I’m gone.

My writer brain is a clear slate ready to absorb any and all there is to see and learn these next two weeks. My work in progress (WIP) that has been brewing and percolating just happens to be set in Paris. I’m ready to begin this new adventure, figuratively and literally. My only hope is that with these months cooped up in my office pounding away on a keyboard, my brain doesn’t explode from all the stimuli and writing fodder. Since my husband continues to remind me that sitting is the new smoking, my walking shoes are packed, so I know my feet are ready for the adventure.

Wishing everyone safe travels this summer.

Au revoir, amis écrivains.

Four years ago when our daughter was looking at colleges, the term semester abroad was of great interest to the entire family. There was no question that our daughter would be studying in a foreign country. We were excited about the idea that after my daughter’s semester abroad, we would be traveling to wherever she was studying to “pick her up”. Fortunately, her semester abroad was spent at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich UK, where she was able to take some great publishing and English Lit classes. And, an amazing three-week spring break romp around Europe, may I add?

Last time we were in London, I was pregnant with my daughter, who turned 21 this week. In other words, it’s been a long while. We went for the London Toy Show, in February. I can only hope the weather is going to be a little better than last time. Our apartment is on the Thames River, feet from where the Mayflower sailed. I’m mentioning all this for several reasons. First, I have nothing but the trip on my brain. Second, my writer self is so excited at the thought of being in the midst of all that history.

After a week in London with side trips to Cornwall, Oxford and possibly Dover, we head to Paris; which I think a certain husband promised me about 20 years ago.

Things are free and clear on the work front. With one publisher, I just signed the release forms, so that book is now off to the printer. With another publisher, I just completed the edits with my project editor, after two rounds of edits with my editor. Women of Steel and Stone is now off to the copy editor. And, hopefully, a new book proposal will make magic at an acquisition meeting, while I’m gone.

My writer brain is a clear slate ready to absorb any and all there is to see and learn these next two weeks. My work in progress (WIP) that has been brewing and percolating just happens to be set in Paris. I’m ready to begin this new adventure, figuratively and literally. My only hope is that with these months cooped up in my office pounding away on a keyboard, my brain doesn’t explode from all the stimuli and writing fodder. Since my husband continues to remind me that sitting is the new smoking, my walking shoes are packed, so I know my feet are ready for the adventure.

Wishing everyone safe travels this summer.

Au revoir, amis écrivains.

Published on May 24, 2013 02:00

May 23, 2013

The Voices Made Me Do It

Last week I had the good fortune to be on the panel that Deborah Heiligman wrote about Tuesday. Preplanning conversations and postmortem drinks at the very literary Algonquin Hotel gave Deb, Marfe’ Ferguson Delano, and me plenty of time to talk about the writing process. These conversations got me thinking about

“voice.” Finding the right voice for a nonfiction book fits somewhere in the

scheme of things between the research and final draft.

You know

how writers of fiction and deranged people – that may be an oxymoron – say,

“It’s the voices … it’s the voices that made me do it?” That makes perfect

sense to me. My books, primarily based on interviews with young people,

absolutely must be true to the people featured. So after an interview, I

transcribe and replay their tapes over and over again as a way to get their

voices into my ears. My journey to understanding “voice”

in writing began as an act of embarrassment and humility.

My Confession:

Once upon a time, long, long ago, after photographing four

children’s books, I decided to try my hand at writing as well as illustrating.

My first, full book contract was about a thirteen-year-old foster boy who spent

a year socializing and loving a puppy that would later become a guide dog for

the blind. What made the boy unusual was that he himself was slowly going

blind. The book was called Mine for a

Year.

After the usual gazillion drafts,

the manuscript was ready to meet its editor. At that time I knew very few

children’s authors and needed a critical read. A magazine editor-cum-good

friend, a brilliant writer himself, said he’d take a look at it. Before he

could change his mind I was sitting in his office with my beautiful, perfect,

gorgeously written first book. He turned to the first page. “WHAT IS THIS CRAP?” He didn’t say

crap. “I’m not going to read this! There’s nothing happening here. There’s no

voice! It’s not you. It’s not the kid.” I grabbed the pages and flew out of

the office. I was devastated, furious, and very

embarrassed.

Once home I spent weeks trying to figure out how to make

this boy read real. What could I do differently? Why didn’t the photographs

alone create the boy’s character? And what is this thing called “voice” anyway?

A week or so later an Aha moment

arrived. Since it was the boy’s story, why not let him tell it?

I rewrote everything in the first person, and

interviewed the boy again to add material and to make sure what was written

matched the way he spoke. We collaborated. We made changes together.

After more than a few drafts,

it was back to the mag editor for round two. With one eyebrow raised - he never

once looked up - he opened to the first page, and read it. Think long, horrible

pregnant pause here. “Okay, now you have voice. Now I want to read this.” For the most part, I’ve been

writing in first person ever since.

A number of INK writers have said how hard it is to come up

with a topic each month. I for one would love to know how you treat voice in

your books.

Published on May 23, 2013 02:00

May 21, 2013

Interview with Chicago Review Press Publisher, Cynthia Sherry

I first visited Chicago Review Press, located in a vintage

brick building not far from the Loop in 1996 to do some editorial work on my

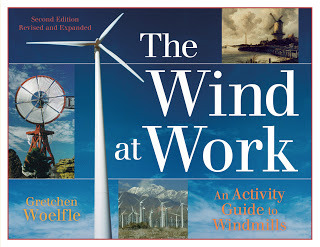

first book, The Wind at Work. At that

time CRP occupied one floor of the building. I remember a delicious Italian

lunch with the staff at a nearby restaurant. (LA doesn’t have an Italian

population, so I hunt down the pasta in Chicago, Brooklyn, SF – and Italy too!)

Fast forward to Summer 2012, and another trip to Chicago. I

had just flown in from New York, in time for a late lunch – French this time –

with Cynthia Sherry, before she took me on a tour of the expanded offices of

CRP – now filling the entire four-story building with Independent Publishers

Group (IPG), its distribution arm. We talked about how Chicago Review Press had

fared – very well, thank you – in the intervening fifteen years, and I’m

pleased that they have just published an updated edition of The Wind at Work.

Cynthia Sherry, publisher of Chicago Review Press, has been

with the company since 1989, where she acquires books, oversees the editorial

and book production of about 65 titles a year, and manages a staff of ten.

Cynthia is a graduate of Grinnell College in Iowa, where she majored in English

and met her husband, musician Rick Sherry. They live in Chicago with their two

daughters.

Tell

me a little about the background of CRP.

Curt Matthews, a graduate student at the University of Chicago and

poetry editor for Chicago Review

magazine, had come across some wonderful works that were too long for the

journal, and in 1973 he and his wife Linda decided to publish them out of their

basement. They received permission from the University of Chicago to call their

fledging company Chicago Review Press. The name had cachet and many of the early

publications were Chicago-centric, including a very early graphic novel called Prairie State Blues.

In 1975 the press published The Home Invaders: Confessions of a Cat

Burglar, by Frank Hohimer, who was doing time at Joliet Correctional

Center. CRP sold the film rights and the film Thief, based on Hohimer’s book, was released in 1981. Income from

that film propelled the company forward. Four decades and many successes later,

Chicago Review Press now publishes about 65 nonfiction titles each year and is a sister company to Independent Publishers Group

(IPG), one of the largest book distributors in North America.

Chicago Review Press has always focused on

publishing titles of lasting interest. Some of our titles have been in print for more than 20 years. We also believe in developing new voices and taking chances

on quirky and sometimes controversial subjects. With more than 700 titles in

print and e-book formats, Chicago Review Press publishes history, popular

science, biography, memoir, music, film, and travel, among others. Our

award-winning line of children’s activity books and young adult biographies

make up 25% of our list. The company is proud to remain independently owned and

minded.

Why

do focus on activity books for children? Who is your audience?

We generally focus on activity books because we feel that hands-on

activities expand learning and are fun for kids. The primary audiences are

educators, homeschoolers, librarians, and engaged learners ages 9 & up. We

don’t dumb the material down for kids and we typically provide a lot of

interesting sidebars that put the subject in the context of the era. Recently

we launched a young adult biography series called “Women of Action” that has

been well received, and we will likely expand in the coming years.

The

first edition of The Wind at Work stayed in print for fifteen years! Other

publishers whisk books out of print in a few years. Why are you

different?

We are very focused on publishing books that will backlist well and we are more

patient than the larger New York publishing houses. Sometimes we publish a book

that’s ahead of its time or for a niche market that requires more work and time

to penetrate. Getting books into the National Parks, for example, can take a

year or more because they want to see the finished book and they have review

committees looking over the content carefully. Lots of children’s books will

receive reviews months after publication and parents and teachers want to know

that the material has been time-tested. The

Wind at Work is an example of a unique book whose market grew over the

years as wind technology became more prevalent.

Other

publishers suffered in the 2008 economic downturn. What happened at CRP?

We were large enough to withstand the economic downturn, but small enough to

be flexible and make appropriate changes to our business model. We were quick

to convert our backlist titles to ebooks. We have also been fiscally

conservative over the years and that put us in a great position to build our

business and invest in new technology while other companies were downsizing and

retrenching. Also, we don’t pay large advances and that has protected us over

the years from any big downsides in the risky business of publishing.

What

are you doing with ebooks?

We embraced ebooks from the beginning and converted all of our backlist

titles into the three ebook formats. It’s definitely a growing segment of the

publishing business, but where it will level out is anyone’s guess. I think it

will end up being at least 30% of the business, but perhaps as much as 50%.

Ebooks currently represent about 20% of CRP’s overall sales, but I think there

is a lot of growth potential as younger readers growing up with handheld

devices become book buyers. That said, I also think that print is here to stay

and that some books lend themselves better to a print format, namely picture

books and heavily designed books.

What

do you see in CRP’s children’s book future?

We will likely branch out and try new things, but slowly. Right now we are

working on developing a few new series like our “Science in Motion” series for

ages 9 & up and our “Women of Action” biography series for young adults. We

will pay attention to common core standards and STEM as we move forward and try

to grow our library and education markets. We like science and building things,

so activities will stay in the mix. As for now, fiction and picture books are

still too risky for us, but who knows what the future will bring for CRP.

Published on May 21, 2013 21:01

Compleat Biographer Conference, A Report: Sphinxes, Secrets, Virgin Eyes

This past Saturday, Susan Kuklin, Marfé Ferguson Delano and I were on a panel at the Compleat Biographers Conference

here in New York City. Tanya Lee Stone was supposed to be with us, but unfortunately

could not come. (We missed you, Tanya!) Thanks to Gretchen Woelfle for telling us about the call

for YA biography writers. This organization is relatively new (2010) but I think they have a good thing going.

We had a fun time planning the panel Friday night over a lovely meal and a bottle of wine. We sat next to a man with very strange facial hair, just a line from his lower lip down his chin. Not a soul patch, more like a soul line. (That was a detail you needed, right?).

Anyway, we decided that the best kind of panel is a conversation, not just talking heads. So we didn't over-plan--we wanted the conversation to be real, and it was. Marfé was the designated moderator, and she did a terrific job. And it is always fascinating to

listen to how Susan does her work. (There was an collective gasp in the room when she talked about interviewing a young man who had been on death row since he was a kid.) People asked really good questions. One

question was, naturally, is writing a biography for kids different from

writing one for adults, and if so, how? And our answers were—it isn’t different, it is different,

and in the end I think we agreed that all writing is about choices and some of

the choices we make when we write for kids we make because we are writing for

kids—and for their gatekeepers. But other than that, it isn't different at all. (Marfé wisely had started our session with an anecdote about someone saying she was sure writing for kids was easier than writing for adults. We dispelled that notion immediately.)

There was one high school teacher in the audience and I found myself looking to her often for agreement, nods, approval. Do those of you who speak to audiences do that? Find one or two people you look at to gauge how you're doing? (It's much better, by the way, if you focus on the happy, nodding people rather than the bored, angry-looking, or sleeping people--if you have any of those. We didn't. But I've learned that nice little lesson over the years...)

Happily, there was also another YA author in the room, Catherine Reef. Marfé had been on a panel with her at this conference in D.C. two years ago, and asked her to chime in. Catherine did, and she really added to our discussion!

I left our panel feeling inspired and renewed, which is

always a good thing. I left the conference, also, with nuggets of knowledge and

inspiration, and I will share those I remember with you. Maybe Marfé and Susan will remember more...

Nuggets:

*Will Swift presented the BIO AWARD to Ron Chernow. In his introduction Swift told that audience that we should all read the prologue

to Chernow’s Washington book. I did and it's terrific. It's about Gilbert Stuart painting Washington's portrait, and is really an essay about writing biography, about how we try to capture real people, not just their likenesses. I recommend it to you, too. (And now I really want to read the whole book.)

*Swift said that Chernow is a master at shedding light on

things that their characters are trying to hide from themselves.

*Interestingly, soon after Chernow himself said, in his speech, that writing a biography is an act of intellectual presumption!

*Chernow said truth will emerge in subtle ways even if the people we are writing about are evasive. So many of our subjects are sphinxes. He said that he realized with the help of his

late wife that Rockefeller was revealing who he was by trying to conceal.

*He also said, and I loved this especially, that when you are writing a

biography you need to find the balance between writing the character from the

inside out and from the outside in.

*In working on George Washington, the more Chernow read, the less familiar Washington

seemed. There were dimensions of his life and personality (his meanness, his

temper, his sensitivity) that previous biographers overlooked. Chernow decided

that the 5% who knew him were more reliable than 95% who didn’t.

*He said he learned he had to look at Washington with virgin

eyes.

After lunch we went to a panel about how to deal with black

holes when writing a biography. It started out promising when the moderator

said that you can have black holes in research, in periods of a person’s life,

or in the understanding of our character. In secrets. Yes! Tell us how to deal with them, please! They didn't give us many

answers, sadly.. but here are a few nuggets:

*When you read someone’s memoir or autobiography you have be

suspicious and ask yourself what was the reason they were writing their autobiography

or memoir. Look for what is not said.

*Mythologies make you want to find the real story.

*If there are people still living who knew the person you're writing about, go talk

to them. You want the gossip. (Chernow's 5% or, if you're lucky, more.)

*Writing a biography is really a group project—you are assembling all the

voices of those who will help you.

*If there’s something important you don’t know, that’s part

of the story.

Maybe it was the lights going off and on in that room, or

the daunting feeling of the black hole, but we three decided to leave the conference right after

that panel. Somehow within fifteen minutes we found ourselves at The Algonquin

Hotel, at a round table, having drinks.

here in New York City. Tanya Lee Stone was supposed to be with us, but unfortunately

could not come. (We missed you, Tanya!) Thanks to Gretchen Woelfle for telling us about the call

for YA biography writers. This organization is relatively new (2010) but I think they have a good thing going.

We had a fun time planning the panel Friday night over a lovely meal and a bottle of wine. We sat next to a man with very strange facial hair, just a line from his lower lip down his chin. Not a soul patch, more like a soul line. (That was a detail you needed, right?).

Anyway, we decided that the best kind of panel is a conversation, not just talking heads. So we didn't over-plan--we wanted the conversation to be real, and it was. Marfé was the designated moderator, and she did a terrific job. And it is always fascinating to

listen to how Susan does her work. (There was an collective gasp in the room when she talked about interviewing a young man who had been on death row since he was a kid.) People asked really good questions. One

question was, naturally, is writing a biography for kids different from

writing one for adults, and if so, how? And our answers were—it isn’t different, it is different,

and in the end I think we agreed that all writing is about choices and some of

the choices we make when we write for kids we make because we are writing for

kids—and for their gatekeepers. But other than that, it isn't different at all. (Marfé wisely had started our session with an anecdote about someone saying she was sure writing for kids was easier than writing for adults. We dispelled that notion immediately.)

There was one high school teacher in the audience and I found myself looking to her often for agreement, nods, approval. Do those of you who speak to audiences do that? Find one or two people you look at to gauge how you're doing? (It's much better, by the way, if you focus on the happy, nodding people rather than the bored, angry-looking, or sleeping people--if you have any of those. We didn't. But I've learned that nice little lesson over the years...)

Happily, there was also another YA author in the room, Catherine Reef. Marfé had been on a panel with her at this conference in D.C. two years ago, and asked her to chime in. Catherine did, and she really added to our discussion!

I left our panel feeling inspired and renewed, which is

always a good thing. I left the conference, also, with nuggets of knowledge and

inspiration, and I will share those I remember with you. Maybe Marfé and Susan will remember more...

Nuggets:

*Will Swift presented the BIO AWARD to Ron Chernow. In his introduction Swift told that audience that we should all read the prologue

to Chernow’s Washington book. I did and it's terrific. It's about Gilbert Stuart painting Washington's portrait, and is really an essay about writing biography, about how we try to capture real people, not just their likenesses. I recommend it to you, too. (And now I really want to read the whole book.)

*Swift said that Chernow is a master at shedding light on

things that their characters are trying to hide from themselves.

*Interestingly, soon after Chernow himself said, in his speech, that writing a biography is an act of intellectual presumption!

*Chernow said truth will emerge in subtle ways even if the people we are writing about are evasive. So many of our subjects are sphinxes. He said that he realized with the help of his

late wife that Rockefeller was revealing who he was by trying to conceal.

*He also said, and I loved this especially, that when you are writing a

biography you need to find the balance between writing the character from the

inside out and from the outside in.

*In working on George Washington, the more Chernow read, the less familiar Washington

seemed. There were dimensions of his life and personality (his meanness, his

temper, his sensitivity) that previous biographers overlooked. Chernow decided

that the 5% who knew him were more reliable than 95% who didn’t.

*He said he learned he had to look at Washington with virgin

eyes.

After lunch we went to a panel about how to deal with black

holes when writing a biography. It started out promising when the moderator

said that you can have black holes in research, in periods of a person’s life,

or in the understanding of our character. In secrets. Yes! Tell us how to deal with them, please! They didn't give us many

answers, sadly.. but here are a few nuggets:

*When you read someone’s memoir or autobiography you have be

suspicious and ask yourself what was the reason they were writing their autobiography

or memoir. Look for what is not said.

*Mythologies make you want to find the real story.

*If there are people still living who knew the person you're writing about, go talk

to them. You want the gossip. (Chernow's 5% or, if you're lucky, more.)

*Writing a biography is really a group project—you are assembling all the

voices of those who will help you.

*If there’s something important you don’t know, that’s part

of the story.

Maybe it was the lights going off and on in that room, or

the daunting feeling of the black hole, but we three decided to leave the conference right after

that panel. Somehow within fifteen minutes we found ourselves at The Algonquin

Hotel, at a round table, having drinks.

Published on May 21, 2013 00:00

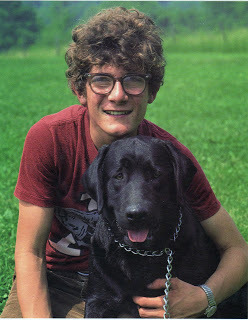

May 20, 2013

Telling Stories

So, for one thing, Ann Bausum's splendid

post

this past Friday, inspires me to show you all my 5th grade picture. It's inspired giggles from many an audience of tactless schoolchildren, bless their hearts.

So, for one thing, Ann Bausum's splendid

post

this past Friday, inspires me to show you all my 5th grade picture. It's inspired giggles from many an audience of tactless schoolchildren, bless their hearts. For another, I'm compelled to inform you that on this day in A.D. 526, a big whacking earthquake in Syria ended the lives of some 300,000 people, about 230K more than have died in the current troubles, since the Arab Spring arrived in that ancient land. Over how many borders the troubles will spill, how many more will suffer, have their lives extinguished, taciturn Heaven only knows. And on May 20, 1768, savvy, rosy Dolley Madison (far the better politician than her brilliant hubby), was born. Exactly 94 years later, President Lincoln found time away from the abysmal war that was consuming his administration in 1862, to sign the far-reaching Homestead Act into law. May 20, 1927? Charles Lindbergh took off from Long Island, bound for Paris. Now imagine the lives, the thoughts, the contexts, the actions, the rippling after-effects, the stories represented by each of those little factoids! Doesn't that just knock you out?

The glorious lake formed by many a long-ago eruption

of the Taal Volcano on the island of Luzon.

And in the center of the lake? Vulcan Point, yet another island.

For yet another thing, in my post last month, I confessed my dire misgivings and oogly-booglies about traveling to Manila. So I did and did not, after all, wind up lost and alone, thousands of miles away from what little savoire faire I possess. I lived to tell the tale of my adventure in the Philippines - but not here. This ain't no travelogue, after all. I'll confine myself to saying that what I saw was glorious (troubling too, of course, being that the divide there between those who have and those who don't is ever so much wider and deeper there than our American chasm between rich and poor) and being with the students at Brent Internat'l School was a tremendous joy. Unlike Ann B. and ever so many others, whose love of their children brought them to writing books for young readers, that bespectacled, introverted 5th grader you see above drew pictures and devoured children's books partly as a means of avoiding my parents' offsprings, i.e. my little brothers. As a grown up greeting card illustrator, I came to children's books because they were the ones that had the pictures! Imagine my surprise when I discovered that a big part of the business of children's books was visiting schools, universally infested (in the sense that P.G. Wodehouse used the term - if you guys only knew how many hours I've drawn and painted whilst listening to Right Ho, Jeeves, about hapless Bertie Wooster and his butler) with little people! Further imagine my surprise when I found out how much FUN it was, visiting with kids - what a big fat, life-affirming, profession-affirming bonus! What it would have meant to my dorky ten-year-old self if a living, breathing writer of books had come to Mrs. Fadler's classroom at Bryant Elementary School!

Can you find me, roosting in the midst of a bunch

of swell kids at Effingham, Kansas the other day?

Of course it's a blast, answering their many questions. Drawing pictures for them. Assuring them that their teachers weren't merely persecuting them when they insisted that revision actually is a key part of the writing process. Repeat after me, I tell 'em, 'All REAL writers/ if they have any self-respect whatsoever/ work on their writing some more. / Oh, baby!' But beyond all of the theatrics (after all any REAL writer is an entertainer, too, and especially if you wish to get and keep the attention of a bunch of lively young squirts), what a large load of joy it has been all these years, talking with young Americans about the vivid, complex life behind each and every one of the famous names they're asked to remember, behind the multitudes whose names we'll never know. Asking them, wouldn't you guys be treated with more respect, be cut some slack if others understood what all you've done and experienced? Your history? Isn't it the same for a nation? A people? Would you not better understand why nations behave as they do, the more you understood those nations' history? Nations are more than borders and banners. A nation is a combination of all of the stories of all of the people who've lived in the land all through the years of the living past! We are, by golly, a story-loving species and never have I been more grateful to have accidentally found myself among those who write them, than when I'm talking about books, these precious story-delivery devices, with a bunch of young readers. And grateful I am and still occasionally surprised that a crabby, shy, paintbrush-pusher like myself should be among these noble nonfiction-meisters, my fellow INKsters, who show and tell what we humans have been about, what we have come to understand about our world, infested with our bumptious species.

Speaking of which, just for you to know, according to a story in Sunday's edition of the Kansas City Star, the Kansas legislature has banned the "spending of any money to implement the national Common Core standards for math and reading" lest the federal government further intrude its control into the workings of the state. (Nor has the KS Board of Ed. seen fit to implement the Next Generation Science Standards.) On the other hand, there's this story , in which some fine points are made concerning this thorny discussion.. In any event, certainly anyone with even a knucklehead's understanding of America's history knows our time-honored push-pull between states' rights/individual rights and federalism, but not since President Lincoln's time has the partisan chasm between Americans been so deep and dangerous. Where this will lead - well, I guess Heaven knows that, too. For now, we can only imagine. And tell the stories.

Read more here: http://www.kansascity.com/2013/05/18/...

Published on May 20, 2013 05:00

May 17, 2013

For the Kids

Susan E. Goodman shared a wonderful tribute to mothers

recently, and the coincidence of my youngest son’s upcoming college graduation

inspires me to add a note of recognition for children.

Whenever I do a school visit, I include a brief introduction

Whenever I do a school visit, I include a brief introductionabout myself. “Here’s me in fourth grade,” I say, soon after the session begins.

“If you’d asked me then what I wanted to be when I grew up, the first thing I’d

have said was, ‘I want to be a children’s book author.’” It made perfect sense.

I loved books. I loved to write. Why not write books for kids? Case closed.

And yet, I tell the school children, I didn’t immediately

become a children’s book author when I grew up. Instead I turned, upon

finishing college, to what I call “more practical writing,” and then I describe the

work I did for ten years with the marketing of books, academic public relations,

and the editing of an alumni magazine.

“It was only when I took a break to have kids,” I tell my

audience, “that I reconnected with that childhood idea to write for young

people.” So I have an easy answer when kids ask, “What made you want to become a

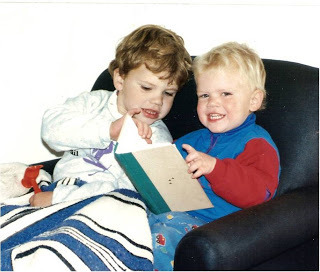

children’s book author?”—“My kids,” I reply. Then I show a childhood photo of

Sam and Jake “reading” Winnie the Pooh together. Hearts melt.

What came next, I tell the students, is the birth of my

writing career. “While I watched my kids grow up, they watched my career grow.

Now they’re in middle school/high school/college (fill in the blank depending on

what year I’ve been speaking), and I’ve published seven/eight/nine books (add

corresponding number of titles).”

Then I show a photo of my two sons at their present ages,

contrasted with the photo of them as young children. Kids eat it up, of course,

because they can see themselves in such a narrative, and I never tire of

telling this story about my life and the lives of my sons.

Sam, Class of 2011, now with City Year

Jake, Class of 2013, Pitzer College

Silly me.

When I first became a children’s author, I thought

that my story was unique. Now I’ve met and heard about dozens of authors who

were inspired to write because of the children in their lives. Their own kids.

Their grandkids. The children they teach. The children who visit the libraries where they work. The

10-year-old child embedded in their own hearts. You know what I’m talking

about!

Yet here we are, writing away for the archetypal young while

our own original sources of inspiration grow toward adulthood and beyond. This Saturday my youngest son graduates from college, and the narrative of my school

visits will have to be updated again. From cuddly boys to grown men. There’s a

tale to celebrate!

So it’s no wonder I’m drawn to visit schools, and you may be,

too, for the same reason. Instantly we are surrounded by the little people who remind us why we

write.

Yes, it helps that our work can pay the bills, and yes, we

write because we were meant to be writers, but we write for young people

because, at the heart of it, we care about their future. If we can just give

them good stories, good history, good science, inspiring knowledge, we will

have, we hope, made a difference.

I always say that being a parent was and is the best job I’ve

ever had. Probably the hardest, too, but by far the most rewarding. Writing for

young people is a very close second! Like parenting, it is a labor of love, born

of the idea of passing on the joy of life to the youngest among us.

Thanks, Jake and Sam, for inspiring me to be a better parent and a better writer. While I'm at it, I commend my fellow authors for writing and sharing your hearts and

minds through your own works, and we all thank those in the wider publishing community who

connect our creations with those smaller hands across the land. All are causes for celebration!

Published on May 17, 2013 00:00