Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 29

April 16, 2013

Writing and Teaching Outside our Comfort Zones

I joke at school visits that my speciality is writing about things I know nothing about. There are no jokes, a boss of mine used to say. She said it with a large measure of meanness, usually when someone had just made a joke. In fact, she was the boss who made me decide to become a freelance writer. Anyway...

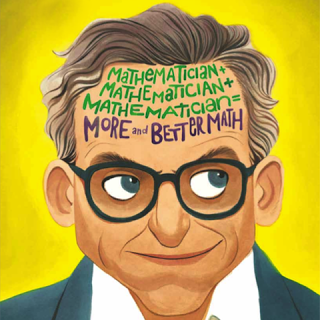

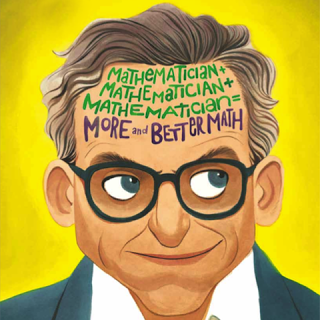

I do, often, write about things I know nothing about. Presumably by the time I'm done writing them, I do know some things. And yet.... A few weeks ago in the New York Times puzzle blog, Gary Antonick wrote about Paul Erdos on the occasion of his 100th birthday. He included some excerpts from The Boy Who Loved Math: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdos.

THAT was WAY COOL. I was dancing. But.... I couldn't understand a bit of the math in Gary Antonick's puzzle. Or in the comments afterward. I didn't try that hard, really. Mostly because I went into a white hot panic. I was so far out of my comfort zone. I passed calculus in high school only because Mr. Hunsberger was a supremely nice human being. No math courses since. And yet I wrote a book about a mathematician.

And I, the author of many science books, took one science course in college--biology for poets. Pass/fail. I passed, thank you very much.

Over the years I have written so many books outside of my comfort zone that I guess those zones have become more comfortable. But that took a long time. Teachers, especially elementary school teachers, tell me they often teach subjects they are not that comfortable with--usually science or math. And yet they find ways to teach outside their own comfort zones all the time.

Recently on Twitter a professor at Fresno State got in touch with me. She was teaching Charles and Emma to her college class of students who want to be English teachers. She wrote:

Kathee Godfrey @cakeypal

11 Apr

@DHeiligman We're going to play with the idea of the writer as scientist, figuring out what your hypothesis was and what you observed

I told her I loved that idea! What a great way to teach that book! And then she wrote back:

Kathee Godfrey @cakeypal11 Apr

@DHeiligman It also might be a how-the-English-teacher-can-infuriate-her-science-colleagues lesson. ;)

I told her I doubted it. Because the trick for her and her students, just as it is for me, is to find the way in. I asked her to tell me how it went. While I waited to hear the results of her experiment I thought more about writing outside my comfort zone--how I do it and why. It's first and foremost about finding a way in.

For me the way in is almost always with the person and the personal story. I am, above all else, a people person. How did Paul Erdos manage to live in this world being very much not of this world? Why was he the way he was? Was he happy? How did other people view him? What excited him about math? How did math change his world and how did he change the world with this math? In answering the questions about him and how he lived his life, I learned why mathematicians all over the world loved him, and still do. I understand the spirit of his math, if not the actual numbers. (Though I admit, I do understand more than Mr. Hunsberger would ever believe!)

Kathee Godfrey reported back that her class was a success. Here's what she wrote:

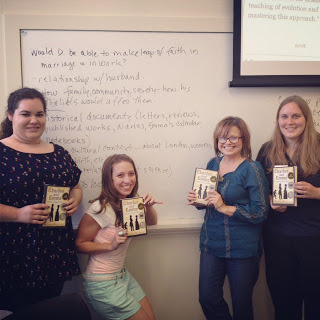

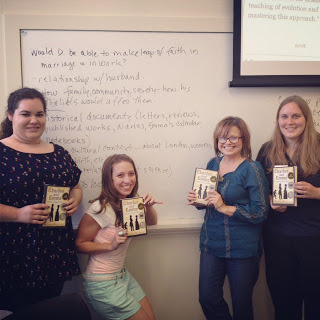

Here is the photo of several of my wonderful students: Dana Resendez, Amelia Sarkisian, Marcella Camino, and Melinda LaRochelle. We're studying your book in a senior seminar on young adult literature and all these students plan to be English teachers. In class Thursday, they came up with hypotheses about what you wanted to illustrate in your book and then identified the evidence or methods to support their hypotheses. It worked surprisingly well!

Brilliant, right? She and her students found the way in, and you can see by their smiles they were happy and proud with the results because they connected. That's all that it takes, right? As E.M. Foster said: "Only Connect."

To read more about the class, go to Kathee's own blog about it, which she calls it, by the way, The Writer As Scientist.

So how do teachers

connect when they are out of their comfort zones? Sometimes they bring in experts to help. Or ask friends behind the scenes. But mostly they rely on books--good, well-researched, entertaining, original nonfiction books for kids--to

help them teach the subject. This weekend I'll be at IRA, talking with reading teachers and other authors about nonfiction and how to use nonfiction books in their

classrooms. (Come say hello--here's my schedule .) I know I will hear more ideas from teachers about how they teach out of their comfort zones. And I know they will tell me books are key.

As to why I write, so often, outside my comfort zone... I think it's because I never want to be bored. I hate being bored. And I love to be challenged. I'm sure there's some other darker reasons, but why go there?

In college I took one art history class, also pass/fail. It was early in the morning, in a large auditorium. There were lots of slides, so the room was darkened. You know what I remember? It's where I learned the word UNDULATING. That is all I remember. I did, however, pass that one, too. With a certain amount of relief.

And now back I go, into the dark, outside of my comfort zone, to my book about--an artist!

I'm starting to think, folks, that my I.N.K. columns are in place of therapy. Thanks for listening.

I do, often, write about things I know nothing about. Presumably by the time I'm done writing them, I do know some things. And yet.... A few weeks ago in the New York Times puzzle blog, Gary Antonick wrote about Paul Erdos on the occasion of his 100th birthday. He included some excerpts from The Boy Who Loved Math: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdos.

THAT was WAY COOL. I was dancing. But.... I couldn't understand a bit of the math in Gary Antonick's puzzle. Or in the comments afterward. I didn't try that hard, really. Mostly because I went into a white hot panic. I was so far out of my comfort zone. I passed calculus in high school only because Mr. Hunsberger was a supremely nice human being. No math courses since. And yet I wrote a book about a mathematician.

And I, the author of many science books, took one science course in college--biology for poets. Pass/fail. I passed, thank you very much.

Over the years I have written so many books outside of my comfort zone that I guess those zones have become more comfortable. But that took a long time. Teachers, especially elementary school teachers, tell me they often teach subjects they are not that comfortable with--usually science or math. And yet they find ways to teach outside their own comfort zones all the time.

Recently on Twitter a professor at Fresno State got in touch with me. She was teaching Charles and Emma to her college class of students who want to be English teachers. She wrote:

Kathee Godfrey @cakeypal

11 Apr

@DHeiligman We're going to play with the idea of the writer as scientist, figuring out what your hypothesis was and what you observed

I told her I loved that idea! What a great way to teach that book! And then she wrote back:

Kathee Godfrey @cakeypal11 Apr

@DHeiligman It also might be a how-the-English-teacher-can-infuriate-her-science-colleagues lesson. ;)

I told her I doubted it. Because the trick for her and her students, just as it is for me, is to find the way in. I asked her to tell me how it went. While I waited to hear the results of her experiment I thought more about writing outside my comfort zone--how I do it and why. It's first and foremost about finding a way in.

For me the way in is almost always with the person and the personal story. I am, above all else, a people person. How did Paul Erdos manage to live in this world being very much not of this world? Why was he the way he was? Was he happy? How did other people view him? What excited him about math? How did math change his world and how did he change the world with this math? In answering the questions about him and how he lived his life, I learned why mathematicians all over the world loved him, and still do. I understand the spirit of his math, if not the actual numbers. (Though I admit, I do understand more than Mr. Hunsberger would ever believe!)

Kathee Godfrey reported back that her class was a success. Here's what she wrote:

Here is the photo of several of my wonderful students: Dana Resendez, Amelia Sarkisian, Marcella Camino, and Melinda LaRochelle. We're studying your book in a senior seminar on young adult literature and all these students plan to be English teachers. In class Thursday, they came up with hypotheses about what you wanted to illustrate in your book and then identified the evidence or methods to support their hypotheses. It worked surprisingly well!

Brilliant, right? She and her students found the way in, and you can see by their smiles they were happy and proud with the results because they connected. That's all that it takes, right? As E.M. Foster said: "Only Connect."

To read more about the class, go to Kathee's own blog about it, which she calls it, by the way, The Writer As Scientist.

So how do teachers

connect when they are out of their comfort zones? Sometimes they bring in experts to help. Or ask friends behind the scenes. But mostly they rely on books--good, well-researched, entertaining, original nonfiction books for kids--to

help them teach the subject. This weekend I'll be at IRA, talking with reading teachers and other authors about nonfiction and how to use nonfiction books in their

classrooms. (Come say hello--here's my schedule .) I know I will hear more ideas from teachers about how they teach out of their comfort zones. And I know they will tell me books are key.

As to why I write, so often, outside my comfort zone... I think it's because I never want to be bored. I hate being bored. And I love to be challenged. I'm sure there's some other darker reasons, but why go there?

In college I took one art history class, also pass/fail. It was early in the morning, in a large auditorium. There were lots of slides, so the room was darkened. You know what I remember? It's where I learned the word UNDULATING. That is all I remember. I did, however, pass that one, too. With a certain amount of relief.

And now back I go, into the dark, outside of my comfort zone, to my book about--an artist!

I'm starting to think, folks, that my I.N.K. columns are in place of therapy. Thanks for listening.

Published on April 16, 2013 00:30

April 15, 2013

Confessions of a Sissypants

"Adventure is just bad planning." Roald Amundsen

"Adventure is worthwhile in itself." Amelia Earhart

So, okay, I've written about many an adventurer.

Seafaring pioneers, living in close, seriously smelly damp quarters, offering up prayers and rationing their limited quantities of foul food and beverage down below the decks of the pitching, tossing Mayflower .

John Adams setting off on horseback [me, I sat astride a horse exactly once, when I was about 9 years old, feeling as if I'd been plunked atop a the broad, warm ridgepole of a living house] to Philadelphia, not quite 400 miles from his Braintree, Massachusetts farm. Picture this earnest, talkative lawyer and his 11-year-old son daring their voyage to France in the winter of 1778. Crossing the Atlantic, whose waves were thick with the ships of His Britannic Majesty, who had less than little use for John Adams or any of the rest of his treasonous buddies at their upstart Congress.

Teenaged Ben Franklin on his own, a runaway apprentice, hiking across NJ to PA. Or stranded in London.

Sister Sojourner, long in years (47 or so), poor in pocket, rich in conviction, setting out on foot to speak the Truth.

Teenaged express riders, each alone but for his pony and mochila full of mail, pounding away through the wilderness.

Dan'l Boone, Adventurer

Daniel Boone. Need I say more? No, I think not.

Teddy Roosevelt. Ditto.

True, setting out to write about someone, some long-gone event is a voyage of discovery. There are suppositions to be challenged. Facts to be discovered and verified. True, one must travel to walk about where others have walked before. Photographing. Sketching. Envisioning the vanished past. Thanks be to all that is holy for historic sites and practitioners of living history at such places as Plimoth Plantation and Williamsburg.

Grateful as all get out am I that I got to do it but it occurs to me that I've not been entirely worthy of writing and illustrating stories about these valiant souls. I'm afraid that my feelings regarding adventures are more aligned with those of Bilbo Baggins: "We don't want any adventures here, thank you!..."nasty disturbing uncomfortable things! Make you late for dinner!" That being said, I'm awash with pre-travel oogly-booglies because way too early tomorrow morning I'm off on one those beastly things. By the time any of you read this post, what I hope won't be part of any posthumous noting of my final efforts, I will have well and truly had an adventure to the Brent International School in Manila. About which I'll write and have pictures for next month's post, God willing.

I'll have had moral support from fellow INK-sters Deborah Heiligman and Susan Kuklin, bless 'em, regarding changing planes in Tokyo. They could have advised me to put on my big girl panties and deal with it, for crying out loud, but they knew to be kind to a rattled soul standing, bags packed, upon a ledge and/or brink. More to the point of this blog, for these 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders on the far side of the world, I shall be conducting writing workshops. Certainly I have done these before and have been charmed, sometimes chagrined, and knocked out more than once by the work of young writers. But because my presentations have generally consisted of 1. my being entertaining and instructive – about history, about writing about history, about finding the facts because making the past come alive but not in some horrid zombie way– before the convened, silent but for their laughter. And 2. a boatload of jolly Q & A. Working with young writers is a comparatively foreign country. An adventure.

In preparation, I'm finding a wealth of information gathered by those who manage classrooms every single day – wait. I must go put on a hat so I may take it off to those who daily convey the nuts and bolts of commas, indenting one's paragraphs, and constructing clear narrative to newbies in acceptable forms of written communication. It occurs to me once more that writing is one skill set, acquired by years of writing and reading; teaching writing, quantifying traits, all six, is entirely another. And nothing is more instructive than preparing to instruct. I'm so eager to meet these young writers, who've been reading my take on the Pilgrims, the Pony Express, Daniel Boone, etc. Oh to BE there, listening, sharing, guiding, and applauding their efforts. If only I didn't need to GO there.

to be continued....

"Adventure is worthwhile in itself." Amelia Earhart

So, okay, I've written about many an adventurer.

Seafaring pioneers, living in close, seriously smelly damp quarters, offering up prayers and rationing their limited quantities of foul food and beverage down below the decks of the pitching, tossing Mayflower .

John Adams setting off on horseback [me, I sat astride a horse exactly once, when I was about 9 years old, feeling as if I'd been plunked atop a the broad, warm ridgepole of a living house] to Philadelphia, not quite 400 miles from his Braintree, Massachusetts farm. Picture this earnest, talkative lawyer and his 11-year-old son daring their voyage to France in the winter of 1778. Crossing the Atlantic, whose waves were thick with the ships of His Britannic Majesty, who had less than little use for John Adams or any of the rest of his treasonous buddies at their upstart Congress.

Teenaged Ben Franklin on his own, a runaway apprentice, hiking across NJ to PA. Or stranded in London.

Sister Sojourner, long in years (47 or so), poor in pocket, rich in conviction, setting out on foot to speak the Truth.

Teenaged express riders, each alone but for his pony and mochila full of mail, pounding away through the wilderness.

Dan'l Boone, Adventurer

Daniel Boone. Need I say more? No, I think not.

Teddy Roosevelt. Ditto.

True, setting out to write about someone, some long-gone event is a voyage of discovery. There are suppositions to be challenged. Facts to be discovered and verified. True, one must travel to walk about where others have walked before. Photographing. Sketching. Envisioning the vanished past. Thanks be to all that is holy for historic sites and practitioners of living history at such places as Plimoth Plantation and Williamsburg.

Grateful as all get out am I that I got to do it but it occurs to me that I've not been entirely worthy of writing and illustrating stories about these valiant souls. I'm afraid that my feelings regarding adventures are more aligned with those of Bilbo Baggins: "We don't want any adventures here, thank you!..."nasty disturbing uncomfortable things! Make you late for dinner!" That being said, I'm awash with pre-travel oogly-booglies because way too early tomorrow morning I'm off on one those beastly things. By the time any of you read this post, what I hope won't be part of any posthumous noting of my final efforts, I will have well and truly had an adventure to the Brent International School in Manila. About which I'll write and have pictures for next month's post, God willing.

I'll have had moral support from fellow INK-sters Deborah Heiligman and Susan Kuklin, bless 'em, regarding changing planes in Tokyo. They could have advised me to put on my big girl panties and deal with it, for crying out loud, but they knew to be kind to a rattled soul standing, bags packed, upon a ledge and/or brink. More to the point of this blog, for these 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders on the far side of the world, I shall be conducting writing workshops. Certainly I have done these before and have been charmed, sometimes chagrined, and knocked out more than once by the work of young writers. But because my presentations have generally consisted of 1. my being entertaining and instructive – about history, about writing about history, about finding the facts because making the past come alive but not in some horrid zombie way– before the convened, silent but for their laughter. And 2. a boatload of jolly Q & A. Working with young writers is a comparatively foreign country. An adventure.

In preparation, I'm finding a wealth of information gathered by those who manage classrooms every single day – wait. I must go put on a hat so I may take it off to those who daily convey the nuts and bolts of commas, indenting one's paragraphs, and constructing clear narrative to newbies in acceptable forms of written communication. It occurs to me once more that writing is one skill set, acquired by years of writing and reading; teaching writing, quantifying traits, all six, is entirely another. And nothing is more instructive than preparing to instruct. I'm so eager to meet these young writers, who've been reading my take on the Pilgrims, the Pony Express, Daniel Boone, etc. Oh to BE there, listening, sharing, guiding, and applauding their efforts. If only I didn't need to GO there.

to be continued....

Published on April 15, 2013 05:00

April 11, 2013

Guest Blogger, Darcy Pattison, Everyone Knows! False Assumptions

I’d like to introduce today’s guest blogger, Darcy Pattison,

an author, blogger, and writing teacher.

Darcy has been published in eight languages. Recent nature books for

children include: WISDOM, THE MIDWAY

ALBATROSS, first place winner in the Children’s Picture Book category of

the 2013 Writer’s Digest Self-Published Book Awards, and a Starred Review in

Publisher’s Weekly; DESERT BATHS, an

NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Book 2013, and PRAIRIE STORMS. Darcy Pattison is the 2007 recipient of Arkansas

Governor’s Arts Awards for her work in Children’s Literature.

As a speaker, Darcy presents programming on her books, and

is well known across the country for her Novel Revision Retreat. Because of her reputation as an excellent writing teacher, Darcy’s blog, Fiction Notes, which offers practical advice on the craft

of writing, has many followers. Her blog can be found at www.darcypattison.com/

Have you heard the old folk song, “Sweet Violets”? It’s a

practical demonstration of setting up an expectation and thwarting it:

There once was a farmer

Who took a young miss

In back of the barn

Where he gave her a. . . lecture

On horse and chickens and eggs

And told her that she had such beautiful. . . manners

That suited a girl of her charms,

A girl that he wanted to take in his. . . washing and ironing

And then if she did,

They could get married

And have lots of . . . sweet violets.

Kids and science are like this. They make assumptions about

a topic and it is sometimes difficult to move them past those assumptions. Take

the subject of baths.

Everyone knows that a bath means lots of soap and water,

right?

Not necessarily.

I heard a story about birds who take baths with ants. Anting

is a well-documented behavior among certain species of birds, and happens one

of two ways. The birds may simply go and stand on an ant nest and allow the

ants to crawl through their wings. Or a bird may crush an ant in its beak, then

use the crushed ant like a washcloth to stroke its feathers. Scientists suspect

that the ants are helping the bird get rid of parasites, such as tiny mites. Or

the crushed ant releases formic acid, which may act as a disinfectant.

When I heard about anting, I wondered how else animals might

take a bath. First, I had to define for myself what a bath meant. Bathing is a

method of hygiene that helps remove dirt, parasites, dead skin/feather cells,

etc. When you remove the assumption that a bath means water, many types of

animal behaviors can be defined as a bath.

It was time to research. To stretch the idea to the max, I

decided to use only desert animals—just to emphasize that a bath doesn’t have

to be water. This did mean some limitations.

I couldn’t include fish. In fact, it was hard to document any cleansing

behaviors from amphibians or arachnids. I stretched the definition to the max

by including a snake (reptile), who sheds his skin as a bath.

The result if my picture book, DESERT BATHS, which was named

a 2013 Outstanding Science Trade Book. For me, the most interesting thing is

how kids stretch their definition of a bath and challenge their initial

assumptions. That’s good science.

Video on You Tube: How Do Desert Animals Take a Bath? Arkansas Audubon Summer Camp

Published on April 11, 2013 22:00

I Can Just Ask!

Today’s post will be short and sweet, partly because I’m

juggling a handful of projects (a process that deserves a whole post in its own

right) and partly because I’m a little hyped:

For the first time in my nearly 20 years of working on

biographies, I am working on a project about a live person.

Waterhouse Hawkins, Walt Whitman, Alice Roosevelt, Mark

Twain and Susy Clemens, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were all lively, and I

tried to bring them to life on the page, but technically, they are no longer with

us.

For the first time, I am working on a book about someone,

happily, who is—who very much is.

Writing about someone long gone has its advantages. You can

utilize the scholarship of others to help inform your understanding of primary

sources. And it’s way easier to determine the lasting significance of someone’s

accomplishments when you can see if it actually lasted.

But there is something amazing about thinking, “I wonder how

she felt about x?” and then realizing, “Oh! I can just ask!”

I’m feeling a little giddy, like a kid in a pastry shop

filling the box with more and more treats. Every day I seem to be emailing a

dozen or so questions (though I was kind enough to give her the whole weekend

off—both days) and then, in a little bit, getting answers.

Will everything make it into the book? Probably not. But the

box is brimming over with treats, and I get to choose the ones I like best.

And then, even better, to ask for more.

Published on April 11, 2013 01:00

April 9, 2013

Nonfiction in Non-Book Form

Let's begin by agreeing that everyone reading or writing for I.N.K. loves books, obviously(!) During my career, many changes have taken place in the publishing industry, from big box bookstores to word processors to personal computers to digital layout and illustration. Recently all this ebook stuff started up...reflowable ebooks, book apps, subscription services, and other innovative ways to deliver "content." (Don't you just love being a content creator and/or a content consumer? Whatever!)

Anyway, I looked into a variety of options, put an o.p. title on iBooks, helped start a group blog about digital books, and spent many hours absorbing blogs/forums/webinars. One criterion is that I must have big, colorful visuals as part of my

digital creations. It's fairly easy to have a text-based ebook up on

Amazon et al without too much difficulty, but it's not relevant for my purposes.

If a publisher wants to do something ebookish with one of my published books, there's no additional effort on my part, probably. But if not enough is happening along that line, many authors have been seeking other options.

After looking into various alternatives and pursuing some, I've come up with these general guidelines for evaluating potential indie projects:

How long does it take to create it?

How "gettable" is it for buyers?

How robust is the marketplace?

And does it have to be a "book?"

In all the excited chatter about this or that innovation, rarely is the cost-benefit ratio mentioned. Sure you can do X, but if it takes months and/or thousands of dollars to do X, how realistic is it for a product that needs to earn its keep via actual sales? I can tell you from personal experience that merely planning an interactive book app (for example) takes eons, much less actually making it. Many of us don't have a lot of spare money or months to gamble away on this or that project that may or may not sell. Trying to learn some new miraculous tech-of-the-moment before it withers away may not be the best use of one's time. Perhaps some "old" technology may be perfectly fine and offers orders of magnitude less hassle. Not to mention that many more potential customers already have the reader or other software installed and they don't have to buy a new device, download an app, or learn a new program.

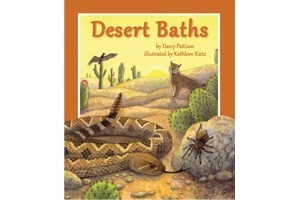

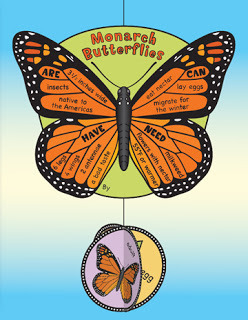

I'm not sure when the idea of getting out of the book "box" dawned on me. The question became: what am I trying to deliver...is it a book, or is it information + fun? So let's say it doesn't have to be a book or a digital book-facsimile. Then what are the possibilities: a game, a play, a song, a video, a hands-on project? Without further ado, here's one nonfiction resource that I've made:

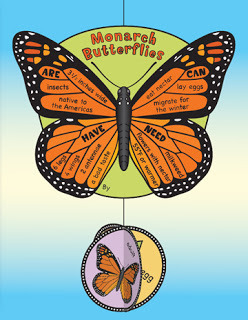

Shown is one part of a PDF that has printable posters, an informational text selection, charts, diagrams, student response pages, plus the butterfly craft where students showcase what they've learned about Monarchs. More info is in this blog post. I have no idea how commonly available this type of hands-on educational activity may be, but based on the feedback so far, teachers and students are enjoying it. And just about anybody with a computer and an Internet connection can download a PDF and already has a printer.

Other non-book nonfiction examples

• Crazy for Similes is a book extention activity in PowerPoint format, another very common program that zillions of people have. This one is a freebie, and has been downloaded over 500 times in less than a month.

• A PDF related to my book Seeing Symmetry has a scavenger hunt, an illustration matching activity, various drawing, cutting, and folding pages, posters, and a real-world symmetry recording sheet.

• On my drawing board is a printable nutrition game related to an upcoming fall book, and nearby are piles and piles of scribbles about ideas from A to Z that I'm dying to work on, just as soon as I finish this book dummy for a publisher.

And what about that marketplace guideline? As far as I know, you can't sell PDFs on Amazon, or if you can, nobody knows about it. My stuff is too big to fit in a dinky little tablet screen (you know I love you, my iPad) and besides, have you ever tried to search for anything in the so-called iBookstore? Apple wants to sell hardware and software, but books, not so much. If they did you could search on "sea turtles" and have my sea turtle book come up, and a bunch of other relevant iBooks that don't necessarily have "sea turtles" in the title or subtitle. And, you could read an iBook on a non-Apple device/computer the way you can read a Kindle book on just about any device. Not to go on a rant, but seriously!

The marketplace that I stumbled over last year is TeachersPayTeachers. With over a million registered users, it's going great guns with just under $7 million in earnings for its sellers in the 1st quarter. The sellers are primarily teachers, who are self-publishing resources that they use in their own classrooms. It's intriguing and just plain fun to cut out all the intermediaries, sell for a lower price, and hear directly from people who are using your creations and who often make suggestions for things they need. There are other options out there for selling digital and hard goods such as Etsy, and other teacher-oriented selling sites.

The best technology in the world is useless if it's too hard for people to utilize, and without a good marketplace for people to buy and sell, nothing much happens. Who knows what the nonfiction ecosystem will look like in 5 years? I'm looking forward to watching it evolve and taking part. Oh, you're probably wondering about my sales, aren't you? It's definitely a learning curve to figure out what people will pay for. Let's put it this way...if all my items sold as well as my top sellers, I'd be a very happy author-illustrator. Just like regular ol' traditional publishing, you make what inspires you, put it out there, and hope somebody will want it!

Anyway, I looked into a variety of options, put an o.p. title on iBooks, helped start a group blog about digital books, and spent many hours absorbing blogs/forums/webinars. One criterion is that I must have big, colorful visuals as part of my

digital creations. It's fairly easy to have a text-based ebook up on

Amazon et al without too much difficulty, but it's not relevant for my purposes.

If a publisher wants to do something ebookish with one of my published books, there's no additional effort on my part, probably. But if not enough is happening along that line, many authors have been seeking other options.

After looking into various alternatives and pursuing some, I've come up with these general guidelines for evaluating potential indie projects:

How long does it take to create it?

How "gettable" is it for buyers?

How robust is the marketplace?

And does it have to be a "book?"

In all the excited chatter about this or that innovation, rarely is the cost-benefit ratio mentioned. Sure you can do X, but if it takes months and/or thousands of dollars to do X, how realistic is it for a product that needs to earn its keep via actual sales? I can tell you from personal experience that merely planning an interactive book app (for example) takes eons, much less actually making it. Many of us don't have a lot of spare money or months to gamble away on this or that project that may or may not sell. Trying to learn some new miraculous tech-of-the-moment before it withers away may not be the best use of one's time. Perhaps some "old" technology may be perfectly fine and offers orders of magnitude less hassle. Not to mention that many more potential customers already have the reader or other software installed and they don't have to buy a new device, download an app, or learn a new program.

I'm not sure when the idea of getting out of the book "box" dawned on me. The question became: what am I trying to deliver...is it a book, or is it information + fun? So let's say it doesn't have to be a book or a digital book-facsimile. Then what are the possibilities: a game, a play, a song, a video, a hands-on project? Without further ado, here's one nonfiction resource that I've made:

Shown is one part of a PDF that has printable posters, an informational text selection, charts, diagrams, student response pages, plus the butterfly craft where students showcase what they've learned about Monarchs. More info is in this blog post. I have no idea how commonly available this type of hands-on educational activity may be, but based on the feedback so far, teachers and students are enjoying it. And just about anybody with a computer and an Internet connection can download a PDF and already has a printer.

Other non-book nonfiction examples

• Crazy for Similes is a book extention activity in PowerPoint format, another very common program that zillions of people have. This one is a freebie, and has been downloaded over 500 times in less than a month.

• A PDF related to my book Seeing Symmetry has a scavenger hunt, an illustration matching activity, various drawing, cutting, and folding pages, posters, and a real-world symmetry recording sheet.

• On my drawing board is a printable nutrition game related to an upcoming fall book, and nearby are piles and piles of scribbles about ideas from A to Z that I'm dying to work on, just as soon as I finish this book dummy for a publisher.

And what about that marketplace guideline? As far as I know, you can't sell PDFs on Amazon, or if you can, nobody knows about it. My stuff is too big to fit in a dinky little tablet screen (you know I love you, my iPad) and besides, have you ever tried to search for anything in the so-called iBookstore? Apple wants to sell hardware and software, but books, not so much. If they did you could search on "sea turtles" and have my sea turtle book come up, and a bunch of other relevant iBooks that don't necessarily have "sea turtles" in the title or subtitle. And, you could read an iBook on a non-Apple device/computer the way you can read a Kindle book on just about any device. Not to go on a rant, but seriously!

The marketplace that I stumbled over last year is TeachersPayTeachers. With over a million registered users, it's going great guns with just under $7 million in earnings for its sellers in the 1st quarter. The sellers are primarily teachers, who are self-publishing resources that they use in their own classrooms. It's intriguing and just plain fun to cut out all the intermediaries, sell for a lower price, and hear directly from people who are using your creations and who often make suggestions for things they need. There are other options out there for selling digital and hard goods such as Etsy, and other teacher-oriented selling sites.

The best technology in the world is useless if it's too hard for people to utilize, and without a good marketplace for people to buy and sell, nothing much happens. Who knows what the nonfiction ecosystem will look like in 5 years? I'm looking forward to watching it evolve and taking part. Oh, you're probably wondering about my sales, aren't you? It's definitely a learning curve to figure out what people will pay for. Let's put it this way...if all my items sold as well as my top sellers, I'd be a very happy author-illustrator. Just like regular ol' traditional publishing, you make what inspires you, put it out there, and hope somebody will want it!

Published on April 09, 2013 23:00

It's Spring and Revisions Are in the Air

The weather is warming up, the sun is shining, and we all want to be outside cleaning up our gardens and getting ready for the summer. Only a lot of us can't! I know at least four people who are feverishly working on revisions right now; mine arrived two weeks ago (along with a gentle hint that if I got it done in a timely fashion the book could be published a season sooner than previously thought).

As it happened, the package arrived when a non-publishing friend was visiting. He'd never seen an edited manuscript, so I showed him a few pages. His eyes went wide, then he blinked a lot and said something like, "Wow, that's a lot of green ink. I'd be really pissed off."

I'm sure that the process I go through with a revision is similar to a lot of other writers. I'm thinking it's a bit like grieving for a dead pet. Various painful stages have to be weathered in order to come out on the other side. So I explained it to him.

First, I glance through the manuscript carefully to get a sense of what needs to be done. I stop from time to time to read a comment in the margin. And sometimes I do become angry. But never at my editor. My editors (I have three) are all very smart and knowledgeable. I get angy at myself for not producing a perfect manuscript, one they would read and say there's nothing more to do. Ah, wouldn't that be nice? To write a perfect manuscript. But that's impossible, so I get angry at myself in order to motivate myself to dig into the text and make it as good as possible. There's a bit of the high school cheerleading emotion here, but it seems to work. For me anyway.

Second, I start at P. 1 and begin addressing the problems my editor has highlighted. I was once an editor, so I always do my own editorial suggestions well before I get those from my editor (and I can be really nasty about my writing); so I add my comments/suggestions to the list. Also, my lovely wife Alison and my agent will sometimes offrer suuggestions.

Initially, I attack the easy stuff. Mispellings (I am not very good at spelling) and grammar (I happen to be very creative when it comes to punctuation). My aim here is to correct the obvious mistakes, but even more important to become comfortable again with the text (after all, it can be weeks, sometimes months since I last reread the text). Then I go back over the manuscript to answer some of the harder questions and suggestions. This phase often requires additional research of one sort or another.

It's hard to say how many times I have to go over the text before I've answered all of the questions. I can only say it is not just once or twice; maybe closer to a dozen or so times. Eventually, I can sit back and say that I've satisfied my editor, myself, my wife and agent -- that the text is a lot better than it was when I sent in the original draft. Am I done? Not by a long shot.

Here's where I enter phase Three. I put the manuscipt aside for several days and try to forget about it. Not an easy thing to do. After a while, I will open the manuscript and make believe I am reading it for the very first time, with an eye to catching any repetition, any line that seems fuzzy, any idea that needs to be fleshed out a little more, any sentence that feels as if I had worked on it, etc., etc. I want the information and the themes to be accurate and clear, but I also want the text to have a smooth, graceful flow.

After I finished explaining this to my friend, he said (and I think he meant this as a compliment), "And here I thought you spend most of your day reading or taking naps." I do, of course, read a lot and I also think napping is a much underappreciated art form. But right now I have to get back to this revision, where I'm still working through the Second phase. With every page revised, I'm a step closer to getting out into the sunshine.

As it happened, the package arrived when a non-publishing friend was visiting. He'd never seen an edited manuscript, so I showed him a few pages. His eyes went wide, then he blinked a lot and said something like, "Wow, that's a lot of green ink. I'd be really pissed off."

I'm sure that the process I go through with a revision is similar to a lot of other writers. I'm thinking it's a bit like grieving for a dead pet. Various painful stages have to be weathered in order to come out on the other side. So I explained it to him.

First, I glance through the manuscript carefully to get a sense of what needs to be done. I stop from time to time to read a comment in the margin. And sometimes I do become angry. But never at my editor. My editors (I have three) are all very smart and knowledgeable. I get angy at myself for not producing a perfect manuscript, one they would read and say there's nothing more to do. Ah, wouldn't that be nice? To write a perfect manuscript. But that's impossible, so I get angry at myself in order to motivate myself to dig into the text and make it as good as possible. There's a bit of the high school cheerleading emotion here, but it seems to work. For me anyway.

Second, I start at P. 1 and begin addressing the problems my editor has highlighted. I was once an editor, so I always do my own editorial suggestions well before I get those from my editor (and I can be really nasty about my writing); so I add my comments/suggestions to the list. Also, my lovely wife Alison and my agent will sometimes offrer suuggestions.

Initially, I attack the easy stuff. Mispellings (I am not very good at spelling) and grammar (I happen to be very creative when it comes to punctuation). My aim here is to correct the obvious mistakes, but even more important to become comfortable again with the text (after all, it can be weeks, sometimes months since I last reread the text). Then I go back over the manuscript to answer some of the harder questions and suggestions. This phase often requires additional research of one sort or another.

It's hard to say how many times I have to go over the text before I've answered all of the questions. I can only say it is not just once or twice; maybe closer to a dozen or so times. Eventually, I can sit back and say that I've satisfied my editor, myself, my wife and agent -- that the text is a lot better than it was when I sent in the original draft. Am I done? Not by a long shot.

Here's where I enter phase Three. I put the manuscipt aside for several days and try to forget about it. Not an easy thing to do. After a while, I will open the manuscript and make believe I am reading it for the very first time, with an eye to catching any repetition, any line that seems fuzzy, any idea that needs to be fleshed out a little more, any sentence that feels as if I had worked on it, etc., etc. I want the information and the themes to be accurate and clear, but I also want the text to have a smooth, graceful flow.

After I finished explaining this to my friend, he said (and I think he meant this as a compliment), "And here I thought you spend most of your day reading or taking naps." I do, of course, read a lot and I also think napping is a much underappreciated art form. But right now I have to get back to this revision, where I'm still working through the Second phase. With every page revised, I'm a step closer to getting out into the sunshine.

Published on April 09, 2013 00:30

April 8, 2013

The Good, the Bad, the Ugly and More

of our writing lives...

Example #1

The Good: A friend/colleague of mine travels all around Massachusetts doing book talks for teachers and librarians. She recently told me that for the past year or more, most of her favorite picture books have been nonfiction. Hands down. The quality and turn of ideas, language and illustrations have been getting better and better.

The Bad: She also said that she and her compatriots have also noticed and discussed that fiction picture books seem to be going through a dry spell. There are peaks and troughs in every genre and, for some reason, there hasn't been a lot of excitement or innovation in that category.

The Ugly: So my friend often urges educators in her audience to use nonfiction books as read-alouds in the classroom to encourage more boys reading, and more nonfiction reading in generally, especially due to Common Core. Yet teachers admit that when they are going to read to the class they still primarily use fiction.

Example #2

The Ugly: Royalty checks often straggle in after March 31st. After opening an envelope, one friend jokingly(?) wondered if he should spend his royalty to pay that month's utility bills or buy a couple tanks of gas.

The Bad: This friend's check reflected the sales of a very well-reviewed and award-winning book.

The Good: My friend got to write the book he wanted to write, on a subject he wanted others to read about. His book was well reviewed. It did win awards. Furthermore, it clearly paid out its advance and got to the royalty stage in this time of school and library cutbacks.

Example #3

The Good: A book I loved writing about the first desegregation case has been acquired by Bloomsbury/Walker, a house I love working for.

The Bad: Although this is my umpteenth book and I should be used to it, the time between acceptance and publication, especially when illustration is involved, is always too long.

The Certain: After Deborah Heligman's delightful and surprising post, I know this book will be published on a Tuesday. And due to its subject matter, whatever year it is published, my bet is it will come out in February.

Published on April 08, 2013 02:00

April 4, 2013

You Write Like a Boy

I recently had occasion to

look through my ninth-grade diary, where I came upon this curious notation:

“English—Miss K. said I write like a boy! Thanks!” Needless to say, this entry

brings up some questions:

Why, exactly, did Miss K. think I wrote like a boy?

Was her comment meant as a compliment or a criticism?

When I wrote, "Thanks!" was I expressing sarcasm or pride?

I’ve thought long and hard

about my English teacher’s comment. From my current perch as a journalistic,

nonfiction author, I wonder if she had picked up on the fact that my writing

tended to be more reportorial than emotional. Was there a dispassion in my ninth-grade

writing that she pegged as “masculine”? Did I rely more heavily on verbs than

adjectives and thus not write flowery prose? Or was it the content that made

her draw that conclusion? I don’t know which piece of writing prompted her

comment, but in those days, I know I wasn’t writing about sports. Still,

perhaps the protagonist in a story I wrote was more self-confident than those

of the other girls in my class. I guess it will remain a mystery.

As for the second question,

I’m hoping it was more of an observation than either a compliment or criticism.

To put the comment in historical context, it was written in 1969, when the

second wave of feminism was in full swing. I don’t recall Miss K. being a

feminist. (She was known as “Miss” K., but that was before “Ms.” became a

popular option.) I asked my brother, who had her as a teacher a few years after

me, but all he remembered was that she was “cute.” I remember her being

relatively new to the profession, and perhaps not as nurturing or supportive as

some of my more memorable instructors. Still, I’d like to give her credit for

being evolved enough not to criticize me for my writing voice. So I’ll take her

words as either a compliment or an observation.

Alas, to the third point, I

think I really did feel proud of her assessment. In the late 1960s, men got the

great jobs and had the adventures that girls like me secretly wished we could

have. I never wanted to be a boy, but

I did read Boy’s Life and fervently wished

I could go on the escapades chronicled in that magazine. In my mind, by saying that I wrote

like a boy, Miss K. was telling me she thought I was tough and adventurous.

That meant I might have the stuff to pursue a worldly career beyond marriage

and childrearing. So I am 99 percent sure that I was expressing pride, rather than sarcasm, when I wrote, "Thanks!"

In my quest for

enlightenment about my diary entry, I pulled out my ninth-grade yearbook

and looked up Miss K. Yep, now I remember her. She even signed my yearbook.

Here’s what she wrote: “You certainly have the ambition and ability to go very

far in life. Best of luck and success to a very intelligent girl.” Now I wonder

if it was my ambition and drive that she thought were masculine. I was always

pretty competitive, whether in gym or in English class. And since this was

three years before Title IX started to level the playing field for women and

men, ambition wasn’t exactly an accepted part of a high school girl’s DNA.

Of course, one conclusion I

could draw is that Miss K.’s comment said more about her than it did about me.

Today, when gender roles are somewhat fluid and political correctness is

paramount, I can’t imagine any teacher thinking,

let alone telling a girl she writes

like a boy, or visa versa. Though I suspect most teachers wouldn’t have voiced those

thoughts in 1969, either, maybe it was an acceptable faux pas for a young woman

just out of teachers’ college.

At any rate, I suspect I've spent a lot more time thinking about Miss K.'s comment now than I did when she originally made it.

Published on April 04, 2013 21:30

Believe It or Not! (A Guest Post by David Elliott)

A guest post by my friend and colleague at Lesley University, David Elliott

As an elementary school kid, the closest I came to

voluntarily reading nonfiction were the Ripley’s

Believe It Or Not bubble gum cards I bought for a nickel every Saturday

morning at Jackson’s Newsstand. Even

now, I can hear the satisfying crinkle of that red cellophane as I peeled it

away from the pink slab of brittle gum and the slippery, sugar-dusted card

beneath it. And I’ll never forget my favorite card, the one about that guy who ate

a truck, bumper to bumper. Ripley’s, by the way, is still around and still

connected to the malleable world of gum. Check it out.

But when Mrs. Stevenson, my funny and terrifying

sixth grade teacher, passed out the orange books that were filled with dates

and names and other info lethal to the imagination about, oh-my-god, the

Presidents, I felt a sudden, uncompromising urge to see the school nurse. I was a dreamy kind of kid, one whose life at

home was filled with enough cold, hard facts to last a lifetime. I craved the

escape, the relief, that fiction offered.

No wonder I became an author of picture books and middle grade novels. How

odd then, that in my most recent work – a poetry series illustrated by the

wonderfully talented Holly Meade --On the

Farm, In the Wild, In the Sea --

many of the reviews mention the amount of real information the poems contain.

But I shouldn’t have been surprised; the inspiration

for many of the poems came from the facts I learned during the many hours I

spent reading about the animals. When I discovered, for example, that while a

leopard has spots, a jaguar has rosettes, I knew I’d found the beginning

lines of my jaguar poem.

The

jaguar’s back is flowering

with

delicate rosettes

as

if she’s grown a garden there...

And who

knew that a female sea turtle has to reach the ripe old age of thirty before

she can lay her first clutch of eggs?

[She] swims the seven seas

for thirty years,

where

she was born

then

finds the beach

With many of the poems, I found that unless I

included a fact, it was nearly impossible to say anything interesting or new.

Dear

Orangutan,

Three cheers to you man of the forest.

You

arrived here long before us . . .

Orangutan is a Malay word. It means man-of-the-forest.

The more I wrote, the more I discovered that hard

fact expanded the world of my imagination. This was never more true than when

writing about the prehistoric creatures featured in the forthcoming In the Past.

I was excited about the opportunity to write the

poems, partly because the idea had come during a school visit. I was standing

in the cafeteria, haplessly blinking at the very, very yellow trays of macaroni

and cheese, when a second grade boy came rushing up to me. “You have to do a

book of poems about dinosaurs,” he panted, tugging on my sleeve. “You just have

to!” My editor agreed. (Okay, maybe she

didn’t think I had to, but she liked

the idea.)

When I sat down to write about dinosaurs though, I

found that the only thing I could think of was that most of ‘em were big. Not a

very interesting book. But by the time I

had finished with my research, I had become a kind of annoying know-it-all

junior paleontologist on the subject of prehistoric fauna. I had a homemade

chart of the geologic eras taped to the wall, along with a timeline of the

animals I wanted to feature. Brachytrachelopan tripped off my tongue as if it had been my

first word. And in every single poem

there is a fact, though it may sometimes be hidden. Here’s an example.

Trilobites

So

many of you.

So

long ago.

So

much above you.

Little

below.

Now

you lie hidden

deep

in a clock,

uncountable

ticks

silenced

by rock.

A nice poem. I think (if you’ll allow me to say

so), but it becomes a better poem when you learn that trilobites are, in fact,

the ancestors of that modern day scourge – the tick.

It has been a lucky surprise, too, to see the way

the blending of fact and poem seem to fit so nicely with the language arts standards

of the Common Core --“Research to Build Present Knowledge” for example, with “Craft

and Structure” and/or “Integration of Knowledge and Ideas.” On a more personal

level, I feel just as lucky that the process of writing these books has opened

me to the poetic possibilities contained in a single fact.

Believe it or not, one day I may even try to write

some prose non-fiction. But one thing is certain: I’m not going to eat any

stinkin’ truck.

Published on April 04, 2013 02:00

April 2, 2013

Winning the Nonfiction War

Early in my career, before Science Experiments You Can Eat was published in 1972, I contracted

to write a book on how money works for a series called "Stepping Stone

Books." I had written a few books called

“First Books” for Franklin Watts (now an imprint of Hachette) but this

assignment was with a new publisher, Parents’

Magazine Press (which apparently no longer exists). I entitled my book Making Sense of Money, and set about creating it. I remember that it was a struggle. I had to

educate myself in economics (not my strong suit) and actually read (plowed

through) Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations.

I labored long and hard before I finally

sent it off to my editor (now long deceased).

She returned the manuscript with a cover letter so scathing that I

destroyed it (now, I wish I hadn’t) but I well remember her searing criticism:

“Your manuscript shows little thought or care.

Writing for children is a serious business. You have a lot of nerve thinking you can do

this.” The returned script was covered with blue pencil. (Daggers to the heart!) My husband was outraged. He thought I should

tell her to go do something unmentionable.

“But we need the money,” I said.

So here’s what I did:

By return mail I wrote:

“Dear Lillian:

Thank you for your comments.

I’m sorry that I disappointed you.

I hope my next attempt comes closer to your expectations.”

I couldn't look at the script for three weeks. Then I bit the bullet, took myself by the

scruff of my neck, and forced myself to rewrite, paying close attention to

every comment, conceding to her language whenever possible. My pain and efforts paid off. The book was published and I went on to write

three more for her. A number of

other authors, more prominent than I, also worked for her in the Stepping Stone

series. When I read their books I noticed that we all sounded exactly alike.

Lillian stifled each author’s voice with her heavy-handed blue pencil to create a uniform style in a multi-author series. Clearly, she knew how to shape us up to

fulfill her vision for the books. (Now, when I want an example of bad writing to show students, I

use my own first paragraph of one of those books.)

That was my first clash with an editor, but not the

last. Over the years I have fought many

battles for various creative aspects for my work; won some and lost some. But I

don’t think I’m unique. My personal story is representative of countless editorial

skirmishes many other nonfiction authors have also engaged in, initially

to gain a place at the table as professionals and then later as we keep pushing the envelope to make our genre a true art form.

In 2009 an editor told me that my submission didn't meet

National Education Curriculum Standards and she sent me the link so that I could read them. My first reaction: steam came out of my ears. My book met seven out of eight standards! My second reaction: I can’t do this alone. I’ll bet there’s help

out there from other authors. So I founded

iNK Think Tank from the wonderful and extraordinarily talented community that

is this blog: a small but mighty band dedicated to bringing the books and wisdom of nonfiction authors into the classroom.

Fast forward to 2013:

The “21st

Century Children’s Nonfiction Conference” will take place on the weekend of June 14-16

in SUNY, New Paltz. Bender, Richardson, White (BRW), a nonfiction book packager in the

UK, is the main corporate sponsor. But iNK Think Tank is also a corporate

sponsor. (How ‘bout that!) The conference will provide editorial coaching workshops for new authors, networking for established authors, a forum for nonfiction publishers to discuss the changes in the marketplace, and strategies for teachers for using nonfiction in their classrooms as mandated by the CCSS. Lionel Bender, founder of BRW, asked me to review an editorial he

was preparing for “Publishing Perspectives” a British online magazine. (I’m now

editing an editor; how ‘bout that!) His

editorial, published on March 25, is called“Children’s

Nonfiction Publishing Comes of Age." On the Saturday morning of the conference, I will be telling my story of the evolution of our genre, “Winning

the Nonfiction War,” as the keynote speaker. Hopefully, it will pull more recruits into our cause. Understanding the real world and the various disciplines that explain and describe it needs more than an encyclopedia (or even a wikipedia) and textbooks. It requires many voices and a subtext of humanity.

The name on my birth certificate is, “Vicki Linda;” it

means “beautiful victory.” Hmmmmm…..

Published on April 02, 2013 21:30