Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 25

June 19, 2013

On How Research Can Make You Throw-Up

Being a nonfiction writer is so glamorous! At least that’s

what it looks like from reading the jacket flap bios of many nonfiction

writers and illustrators. After all,

we’ve trekked with gorillas, dived with seahorses, explored dark caves, and

flown up to the Arctic with the Air Force. You might even think that from

reading my books and articles. After all, I’ve hung out with rocket scientists

at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, hiked to the summit of Mount St. Helens when

it was erupting, visited volcano observatories on Mount Merapi with a team of

American and Indonesian volcanologists, and spent sunny days bobbing on the

ocean with wave energy engineers. It IS

pretty awesome. Except for when it’s not.

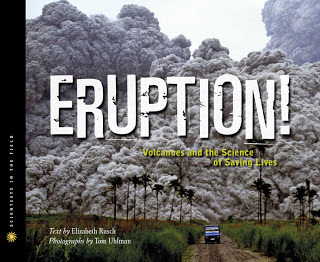

I’m going to tell you a story that you’re not going to find

any suggestion of in my book Eruption: Volcanoes and the Science of

Saving Lives , just released by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on June 18.

Soon after signing the contract to write this book, I got on

the horn to the volcanologists at the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program to

see if I could tag along on any summer field work. Volcanologist Andy Lockhart

told me that his team was helicoptering a small group of Chilean volcanologists

onto the upper flanks of Mount St. Helens to do some maintenance work on a

monitoring station and to install a new one. And he invited me to go! “Wow,” I

thought. “I have the coolest job EVER.”

After a few days, though, he called me back to say that he

was mistaken; government rules would not allow unauthorized personnel on the

helicopter. But he said: If you can find

your own ride…

So I called Tom Uhlman, the photographer hired to shoot the

book, to see if he would be up for splitting the cost of hiring our own

helicopter. He was game, so I priced it out, and we

booked it. I was going to helicopter in

to meet some American and Chilean volcanologists on the flanks of freaking

Mount St. Helens! “Awesome,” I thought. “I have the coolest job in the WORLD.”

A few days later, the helicopter company called. They were

mistaken. There was no way they were going to land their helicopter on an ash

field where their delicate components would get ground up by the glasslike

slivers of ash.

I was heartbroken. There had to be a way…

So I called Andy. “Is there any way we could hike in and

meet you?” I asked.

He didn’t think we could take the usual climbing route

because it’s too snow- and ice-covered and we’d need crampons and ice axes. But

he thought we might be able to go up and around the glacier.

So I called around and found a volunteer guide. He would carry

a radio, a GPS and map. Tom and I packed

our backpacks, hiking boots and hiking polls. We were set.

The hike started out mellow, winding through the woods. We

hopped on a trail that circles the volcano and the sun shone brightly, the sky

was blue, and the wildflowers were everywhere. I thought: “I really do have the

best job in the world…”

Soon we headed off trail up some steep hills full of loose

volcanic skeet. We heard a distant helicopter and caught a glimpse of it far

off, but we couldn’t tell where it went.

We checked our GPS reading and the map

and trudged up canyons and down canyons. We were winded but happy.

Finally, we found the canyon that we thought would lead us

safely to the volcano monitoring station. We were much later than we thought getting

there, but still had many daylight hours ahead of us, so up we went. Up and up

and up. Through skeet piles that avalanched under our feet. Over large rocks

and boulders. And then we faced a huge, steep snow field. The kind where

you’d be better off having crampons and ice axes.

We decided that the guide and I would head up

alone, and Tom would stay with his equipment until we were sure we had found the

right place. (This is Tom, having a much needed rest.)

We couldn’t see or hear the helicopter or any voices. But it was

still a long way up and over a ridge, so we thought maybe it was all hidden from view.

We trudged up, kicking our toes in to the snow to make

shallow steps. Did I mention that I’m a little scare of heights? I just kept my

eyes on the snow ahead and tried not to look down. Then, I lost my footing. I slipped and started shooting down the ice

field, picking up speed. I kicked my heels into the snow and grabbed desperately at the glacier with my hands but I just kept sliding. I was nearing the guide, and

I reached out my hand. In what felt like

slow motion, he grabbed my arm and stopped my slide. We both sat in the snow

for a while, panting.

“Not far now,” I said.

He gave me a gentle look. "I don’t hear anything," he said. "I don't think they are up there. Maybe

we should head back."

But we had come this far. So we trudged to the top and over

the ridge.

This amazing photo of the America and Chilean scientists

working on the volcano monitoring station on Mount St. Helens? I didn’t take

it. Neither did Tom, nor the guide.

That’s because we never made it there.

We hiked over the ridge to find nothing. Nothing but a bunch

of volcanic rubble.

I actually had a tantrum, stomping my feet up and down,

pounding my fists in the air and yelling: “I don’t believe it! Where are

they???” (I was only half joking.)

We estimated that we hiked about 18 miles, with at least

6,000 vertical gain. It was a beautiful day, but I ran out of water long before

we got back to the trailhead (and anyone who knows me knows I am a fiend about

packing ample water.) We hiked out after dark, tired, hungry, and dehydrated

with our legs wobbling from all the vertical (and I run half marathons!)

No one had any energy to drive anywhere. Our guide kindly

offered to put us up for the night. We gobbled down some burgers and a beer and

stumbled off to bed.

But for me, the ordeal wasn’t over. I woke up in the middle

of the night, and I didn’t feel right. I

was surprised to find that my legs felt pretty good as I made my way to the bathroom

– but that’s the only part of me that felt good. Let’s just say that I kissed the

porcelain god.

I cleaned it all up and crawled back to bed. I felt a little shaky the next day, but made

it back to Portland. An email greeted me when I got home: “Where were you? We

had a very successful day and brought you a nice lunch and lots of water.”

To this day, we don’t really know what went wrong. Sometimes

things go wrong.

And that isn’t the only time I’ve had to struggle to hold down

a meal while doing field research. I’m deep in the throes of researching and

writing another Scientists in the Field book about wave energy pioneers –

engineers on a quest to transform that up and down motion of waves into

electricity.

One of my first trips out was a sparkly blue-sky day with

only four foot swells. But stuck inside the boat’s cabin peering out the tiny

windows, trying to interview a scientist and take notes, the waves felt a lot

bigger. After a while everyone on board started to look a little pale and a

little uncomfortable. Someone offered motion sickness medicine and a few popped

the pills. Others sipped ginger ale. And one person – I’m not saying who and it

wasn’t me – threw up off the back of the boat. Several times.

But that’s all in a day’s work.

Care to share any gruesome stories from your research? I

dare you.

Elizabeth Rusch

(Photos courtesy of Tom Uhlman, except the shot at the top, courtesy of USGS scientist Martin LeFevers.)

what it looks like from reading the jacket flap bios of many nonfiction

writers and illustrators. After all,

we’ve trekked with gorillas, dived with seahorses, explored dark caves, and

flown up to the Arctic with the Air Force. You might even think that from

reading my books and articles. After all, I’ve hung out with rocket scientists

at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, hiked to the summit of Mount St. Helens when

it was erupting, visited volcano observatories on Mount Merapi with a team of

American and Indonesian volcanologists, and spent sunny days bobbing on the

ocean with wave energy engineers. It IS

pretty awesome. Except for when it’s not.

I’m going to tell you a story that you’re not going to find

any suggestion of in my book Eruption: Volcanoes and the Science of

Saving Lives , just released by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on June 18.

Soon after signing the contract to write this book, I got on

the horn to the volcanologists at the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program to

see if I could tag along on any summer field work. Volcanologist Andy Lockhart

told me that his team was helicoptering a small group of Chilean volcanologists

onto the upper flanks of Mount St. Helens to do some maintenance work on a

monitoring station and to install a new one. And he invited me to go! “Wow,” I

thought. “I have the coolest job EVER.”

After a few days, though, he called me back to say that he

was mistaken; government rules would not allow unauthorized personnel on the

helicopter. But he said: If you can find

your own ride…

So I called Tom Uhlman, the photographer hired to shoot the

book, to see if he would be up for splitting the cost of hiring our own

helicopter. He was game, so I priced it out, and we

booked it. I was going to helicopter in

to meet some American and Chilean volcanologists on the flanks of freaking

Mount St. Helens! “Awesome,” I thought. “I have the coolest job in the WORLD.”

A few days later, the helicopter company called. They were

mistaken. There was no way they were going to land their helicopter on an ash

field where their delicate components would get ground up by the glasslike

slivers of ash.

I was heartbroken. There had to be a way…

So I called Andy. “Is there any way we could hike in and

meet you?” I asked.

He didn’t think we could take the usual climbing route

because it’s too snow- and ice-covered and we’d need crampons and ice axes. But

he thought we might be able to go up and around the glacier.

So I called around and found a volunteer guide. He would carry

a radio, a GPS and map. Tom and I packed

our backpacks, hiking boots and hiking polls. We were set.

The hike started out mellow, winding through the woods. We

hopped on a trail that circles the volcano and the sun shone brightly, the sky

was blue, and the wildflowers were everywhere. I thought: “I really do have the

best job in the world…”

Soon we headed off trail up some steep hills full of loose

volcanic skeet. We heard a distant helicopter and caught a glimpse of it far

off, but we couldn’t tell where it went.

We checked our GPS reading and the map

and trudged up canyons and down canyons. We were winded but happy.

Finally, we found the canyon that we thought would lead us

safely to the volcano monitoring station. We were much later than we thought getting

there, but still had many daylight hours ahead of us, so up we went. Up and up

and up. Through skeet piles that avalanched under our feet. Over large rocks

and boulders. And then we faced a huge, steep snow field. The kind where

you’d be better off having crampons and ice axes.

We decided that the guide and I would head up

alone, and Tom would stay with his equipment until we were sure we had found the

right place. (This is Tom, having a much needed rest.)

We couldn’t see or hear the helicopter or any voices. But it was

still a long way up and over a ridge, so we thought maybe it was all hidden from view.

We trudged up, kicking our toes in to the snow to make

shallow steps. Did I mention that I’m a little scare of heights? I just kept my

eyes on the snow ahead and tried not to look down. Then, I lost my footing. I slipped and started shooting down the ice

field, picking up speed. I kicked my heels into the snow and grabbed desperately at the glacier with my hands but I just kept sliding. I was nearing the guide, and

I reached out my hand. In what felt like

slow motion, he grabbed my arm and stopped my slide. We both sat in the snow

for a while, panting.

“Not far now,” I said.

He gave me a gentle look. "I don’t hear anything," he said. "I don't think they are up there. Maybe

we should head back."

But we had come this far. So we trudged to the top and over

the ridge.

This amazing photo of the America and Chilean scientists

working on the volcano monitoring station on Mount St. Helens? I didn’t take

it. Neither did Tom, nor the guide.

That’s because we never made it there.

We hiked over the ridge to find nothing. Nothing but a bunch

of volcanic rubble.

I actually had a tantrum, stomping my feet up and down,

pounding my fists in the air and yelling: “I don’t believe it! Where are

they???” (I was only half joking.)

We estimated that we hiked about 18 miles, with at least

6,000 vertical gain. It was a beautiful day, but I ran out of water long before

we got back to the trailhead (and anyone who knows me knows I am a fiend about

packing ample water.) We hiked out after dark, tired, hungry, and dehydrated

with our legs wobbling from all the vertical (and I run half marathons!)

No one had any energy to drive anywhere. Our guide kindly

offered to put us up for the night. We gobbled down some burgers and a beer and

stumbled off to bed.

But for me, the ordeal wasn’t over. I woke up in the middle

of the night, and I didn’t feel right. I

was surprised to find that my legs felt pretty good as I made my way to the bathroom

– but that’s the only part of me that felt good. Let’s just say that I kissed the

porcelain god.

I cleaned it all up and crawled back to bed. I felt a little shaky the next day, but made

it back to Portland. An email greeted me when I got home: “Where were you? We

had a very successful day and brought you a nice lunch and lots of water.”

To this day, we don’t really know what went wrong. Sometimes

things go wrong.

And that isn’t the only time I’ve had to struggle to hold down

a meal while doing field research. I’m deep in the throes of researching and

writing another Scientists in the Field book about wave energy pioneers –

engineers on a quest to transform that up and down motion of waves into

electricity.

One of my first trips out was a sparkly blue-sky day with

only four foot swells. But stuck inside the boat’s cabin peering out the tiny

windows, trying to interview a scientist and take notes, the waves felt a lot

bigger. After a while everyone on board started to look a little pale and a

little uncomfortable. Someone offered motion sickness medicine and a few popped

the pills. Others sipped ginger ale. And one person – I’m not saying who and it

wasn’t me – threw up off the back of the boat. Several times.

But that’s all in a day’s work.

Care to share any gruesome stories from your research? I

dare you.

Elizabeth Rusch

(Photos courtesy of Tom Uhlman, except the shot at the top, courtesy of USGS scientist Martin LeFevers.)

Published on June 19, 2013 03:00

June 18, 2013

Helping Kids Nurture Their Inner Ratters

Last July 8, a Cairn terrier came into our lives. We had been without a dog since Tinka, our beloved Golden Retriever, died in 2004. While in Pennsylvania for a party, we heard about a dog who needed a home, and even though we debated for seven years whether or not we could have a dog in the city (we lived in Bucks County, PA, during the Tinka years), we have not looked back. Ketzie is, as I tell her often, a value-adder in our lives.

There is only one time when I feel at all doubtful about Ketzie. And that's the last walk of the night. Not because I'm too tired, but because the last walk of the night has become THE RATTING WALK.

Before you get too grossed out (or maybe too excited), see below for one of the cuter aspects of the dog being a ratter. Here she is hiding under our bed. "Hiding." Why is she hiding? She has a new toy bone, and she doesn't want us to get it. OR rather, she'd like for us to try to get it, but she wants to put up a fight. She knows it is safe under there.

(Why are there books there? Our bed is a little bit broken. Until we can get our friend Keith to make us a new one, we have to prop it up with something. We have more books than we have space for, so.....)

Where we lived in Pennsylvania, there were mice and moles and skunks and deer. Where we live now, there are rats. Mostly they are hidden. But once in a while, at night, one will scamper across the street or sidewalk in front of us. While my instinct is to jump back, Ketzie's instinct is to become very alert. She assumes a posture we don't see any other time: alert in every cell of her body. It's as if her ratting genes coming to ATTENTION. Cairns were bred to get rats out of cairns (or maybe, truly, out of homes made of stones). And at night, just outside our lovely apartment building, Ketzie is ready to be OF SERVICE.

I don't think we're going to train her to be on the rat-hunting squad. Yes. There is a rat-hunting squad in NYC and that link is to an article and a video about it. Please watch the video. It's only a minute and a half, and so worth it. I'll wait until you come back.

Right? Ketzie really should be on that squad. But considering every night we're (husband and I) terrified she will catch a rat, I don't think it is in her future.

When we have to force her to come back inside--Cairns are stubborn!-- I feel like we're thwarting her most basic nature. Which makes me sad.

Tinka, our Golden, did not understand fetching in our Buckingham back yard. But the first time we threw a stick into the ocean, in Nova Scotia, she swam in, retrieved it, and laid it at our feet. Another clear sign of genes being able to express themselves.

As parents and teachers and writers it is our job to help kids find their true selves. To help them express who they are, who they were meant to be. People who live their lives letting their innermost selves guide what they do are the ones we admire the most. Often those people have to fight inner and outer battles to do so. Paul Erdős was one of those people. He was so lucky that his mother (and later his father) nurtured his love of math, and understood his true nature. Mama let Paul be home-schooled until he was ready for school. She challenged him with math from the time he showed the great interest and ability (when he was four). Later on, the love and support he got from his parents, and the great foundation he had in math, allowed him to go out into the world--on his own terms.

(Shameless and excited plug: THE BOY WHO LOVED MATH is coming out next Tuesday. Check out my website for news, etc.)

Even if we are not math prodigies or ratters or retrievers, we each have inborn strengths and talents that should be nurtured. We each have problems to overcome; everyone has to learn strategies for how to fit into the world. Some, like Paul Erdős, have more of a challenge than others. But with adults in their lives who understand their needs, they have a greater chance at success and a happy life.

As parents, teachers, and dog-owners, we do the best we can. Even though I don't let Ketzie go after rats, I do buy her a new toy every time she destroys her current favorite. I think--I hope--that along with about an hour and half's worth of walks every day, good food, and lots of attention, that's enough. She seems pretty happy, and at home.

There is only one time when I feel at all doubtful about Ketzie. And that's the last walk of the night. Not because I'm too tired, but because the last walk of the night has become THE RATTING WALK.

Before you get too grossed out (or maybe too excited), see below for one of the cuter aspects of the dog being a ratter. Here she is hiding under our bed. "Hiding." Why is she hiding? She has a new toy bone, and she doesn't want us to get it. OR rather, she'd like for us to try to get it, but she wants to put up a fight. She knows it is safe under there.

(Why are there books there? Our bed is a little bit broken. Until we can get our friend Keith to make us a new one, we have to prop it up with something. We have more books than we have space for, so.....)

Where we lived in Pennsylvania, there were mice and moles and skunks and deer. Where we live now, there are rats. Mostly they are hidden. But once in a while, at night, one will scamper across the street or sidewalk in front of us. While my instinct is to jump back, Ketzie's instinct is to become very alert. She assumes a posture we don't see any other time: alert in every cell of her body. It's as if her ratting genes coming to ATTENTION. Cairns were bred to get rats out of cairns (or maybe, truly, out of homes made of stones). And at night, just outside our lovely apartment building, Ketzie is ready to be OF SERVICE.

I don't think we're going to train her to be on the rat-hunting squad. Yes. There is a rat-hunting squad in NYC and that link is to an article and a video about it. Please watch the video. It's only a minute and a half, and so worth it. I'll wait until you come back.

Right? Ketzie really should be on that squad. But considering every night we're (husband and I) terrified she will catch a rat, I don't think it is in her future.

When we have to force her to come back inside--Cairns are stubborn!-- I feel like we're thwarting her most basic nature. Which makes me sad.

Tinka, our Golden, did not understand fetching in our Buckingham back yard. But the first time we threw a stick into the ocean, in Nova Scotia, she swam in, retrieved it, and laid it at our feet. Another clear sign of genes being able to express themselves.

As parents and teachers and writers it is our job to help kids find their true selves. To help them express who they are, who they were meant to be. People who live their lives letting their innermost selves guide what they do are the ones we admire the most. Often those people have to fight inner and outer battles to do so. Paul Erdős was one of those people. He was so lucky that his mother (and later his father) nurtured his love of math, and understood his true nature. Mama let Paul be home-schooled until he was ready for school. She challenged him with math from the time he showed the great interest and ability (when he was four). Later on, the love and support he got from his parents, and the great foundation he had in math, allowed him to go out into the world--on his own terms.

(Shameless and excited plug: THE BOY WHO LOVED MATH is coming out next Tuesday. Check out my website for news, etc.)

Even if we are not math prodigies or ratters or retrievers, we each have inborn strengths and talents that should be nurtured. We each have problems to overcome; everyone has to learn strategies for how to fit into the world. Some, like Paul Erdős, have more of a challenge than others. But with adults in their lives who understand their needs, they have a greater chance at success and a happy life.

As parents, teachers, and dog-owners, we do the best we can. Even though I don't let Ketzie go after rats, I do buy her a new toy every time she destroys her current favorite. I think--I hope--that along with about an hour and half's worth of walks every day, good food, and lots of attention, that's enough. She seems pretty happy, and at home.

Published on June 18, 2013 00:30

June 17, 2013

On a Day Like Today

So, at the time of this writing, it is the 236th anniversary of that June day in 1777 (and the 66th anniversary of Flag Day, 1947: my folks met on a blind date - and should have kept on walking? I don't know, but sometimes I wonder...),when the gents at the Congress, in their smelly duds made of natural fibers, agreed – felicitous notion! – upon a new design for a flag. Yes, they'd keep the 13 stripes. But by now, it clearly did not do to have the standards of England and Scotland crisscrossing that blue field up in the corner. No, there must be 13 stars as well, a "new Constellation." After all: thirteen States = one independent nation. That was the theory, and one that was in serious jeopardy. Even then, a flashy British general and sometime playwright, John Burgoyne, was up in Canada, fixing to raise the curtain on a pretty substantial invasion. And Ben Franklin was in Paris, in the last glittering and glorious, fetid, filthy, unjust decades of l'Ancien Régime , trying to wangle help from the French for the Americans' desperate enterprise. Which they, the people, got after word spread that General Burgoyne's play had flopped in the fall of '77 at Saratoga, NY.

"Gentleman Johnny" Burgoyne

But if you're reading this, dear Lover of Factual Information, you probably already know this and plenty more bits of so-called "trivia." How easy it is to dismiss a brief record of a time/space intersection as a mere "factoid." Each of which representing critical, complex moments in our all-too-human saga. It was on a mid-June day, maybe like today, when Sir Francis Drake [probably every bit as grubby as his crew] sailed along the coast of northern California in 1579. When the ballsy [can I say that? probably not] privateer claimed the land thereabouts for England and "Good [Spiteful, Determined] Queen Bess" and called it [never mind the resourceful hunters who already lived there] New Albion.

It was June 17, 1882 when Igor Stravinsky came into the world. ('Twas May 26, 1913, by the by, when Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky rocked and shocked Paris with the premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps, the Rite of Spring?) And today marks 74 years since the last time French officials held a public execution by guillotine. Ever so much more humane than an axe, non? (Thereafter these ultimate pains-in-the-neck were private.) Who was the man of the hour on that almost-summer day in Paris of 1939? Who took Parisians' minds off their war-worries? A 31-year-old career criminal, Eugen Weidmann.

The Battle of Bunker [Breed's] Hill, imagined by the great Howard Pyle

Just 106 years after Weidmann got it in the neck – two centuries + 38 years ago today – some 1,500 exhausted, filthy, cranky-but-determined colonial soldiers did battle north of Boston. All the day before and late into the night they'd been marching then digging, piling up rocks and dirt, and building fortifications on Breed's hill (where most of the hot fighting would happen). Now,off to the south, a not-quite-8-year-old held his mother's hand as they watched the flames, after the British put torches to Charlestown. 71 years later, old John Quince Adams remembered how he "saw with my own eyes those fires, and heard Britannia's thunders in the Battle of Bunker's hill and witnessed the tears of my mother and mingled them with my own..."

Around 2,500 British soldiers, sweltering in their red wool coats, confronted some 1,500 'patriots.' After all of the drumming, shooting, cannon thunder, shouts and screams, the 'redcoats' could claim a victory, but more than a thousand were hurt or killed. On a day like today, but decidedly not.

Now I'd be remiss and will have been a twit if I did not mention a book or two. Or more.

George vs. George: The American Revolution As Seen from Both Sides, written AND illustrated by brilliant Rosalyn Schanzer.

George Washington, Spymaster: How the Americans Outspied the British and Won the Revolutionary War, by clever Thomas B. Allen.

King George: What Was His Problem? The Whole Hilarious Story of the American Revolution, by that smartypants Steve Sheinkin (illus. by Tim Robinson).

Fight For Freedom: The American Revolutionary War, by Benson Bobrick

The Revolutionary John Adams, George Washington, that I wrote and illustrated. Young John Quincy, too, but it's out of print, the world being rotten and unjust.

Johnny Tremain, by Esther Forbes.

The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, vols. I & II, M.T. Anderson

George Washington's Army and Me, written and illus. by Michael Dooling.

Published on June 17, 2013 05:00

June 13, 2013

Being an Introvert

A few months ago, I wrote about heading out into the world

to write, and the little teashop I sometimes visit when I’m stuck or stalled—to

shake things up and help me see my ideas from a new perspective.

But most of the time, I do my best work at my desk in my

very quiet office, all alone, preferably with the dog snoring quietly at my

feet. I don’t play music, even music without lyrics. I can’t think

with external noise going on. The noise distracts me from what I am trying to hear.

I usually know the basic idea I’m poking/prodding/massaging

into life. I pretty much know the what.

What I’m trying so hard to hear in my little quiet office is

the how. How do I express this idea in writing most authentically mine?

In her wonderful TED Talk, Susan Cain affirms the importance

of solitude, how introverts like me should embrace our need for quiet time. I

learned long ago that I need quiet time and even a quiet life (a modest social

calendar without too many distractions) to find my writing voice.

But Cain also

talks about how introverts should not try to force themselves to be extroverts, and this applies to the other

side of a writing life: going out into the world to talk about my books to

other people.

This has to do with authenticity, as well.

When I first started presenting, almost 20 years ago, I

tried to be more ‘out there’ than I usually was—bigger, badder, louder—the kind of author who

quickly has a room full of first graders shouting back responses in a happy

chorus.

I LOVE authors who can do this, and kids love them, too.

But every time I tried this, it felt like a false note, a lukewarm imitation of someone else. What I needed instead, I realized, was to be the best version of myself I can be.

For me this means sharing my passions: the importance of

following your curiosity, the importance of being open to new people and new

experiences. It also means sharing my enthusiasm for being in awe—of the

amazing things people have accomplished, of all the possibilities out there for

all of us.

And I don’t have to do headstands while playing the ukulele to do this.

I can be this passionate, enthusiastic, amazed and awestruck presenter, quietly talking

to kids, teachers and librarians. I can be my little old self: Thoughtful.

Engaged. A good egg. And an introvert.

Published on June 13, 2013 01:00

June 12, 2013

Try This at Home

Let me tell you about my grandson Elliott.

Let me tell you about my grandson Elliott.I spent the day with him yesterday, and here is a partial list of his achievements:

• rolling from side to side

• taking the top piece (cherry light) off a stacking police car puzzle and looking through the hole that allows it to sit on top of the car

• removing his socks from his feet and chewing on them (the socks)

• whacking himself with a wooden hammer he was trying to whack some pegs with

• sticking out his tongue while trying to swallow food.

You can see the boy has potential. For an eight month old, he is doing the exact right things to develop this pure potential, while appearing (from the outside) to be messing around and doing nothing much productive. I credit his mother, my lovely older daughter Bethany.

When Bethany was small, I gave her an important job: painting the trees. All three of my children had this job during their preschool days; tongue-in-cheek, they accuse me of being an abusive parent because of this job. The job: take a coffee can full of water and a paintbrush outside. Paint all the trees with water so that they change color. When you have finished (and the first trees are dry), start over.

I believe that this, too, helped develop the potential of a child in my care.

Nowadays, I spend most of my days on my own, working in the barn. Recent work includes a series of four books called Science Fair Winners (Bug Science, Crime Scene Science, Junkyard Science, and Experiments to Do on Your Family) from National Geographic. They are designed to take a child's personal interest and build it into a science project with connections to research actually happening in the field. Some of the stuff is fairly high level and somewhat complicated, involving such phenomena as people's response to litter, conflict resolution, sibling recognition based on shared DNA, and so on.

But now I've been asked to take science projects a little younger, and to take them out of the school and lab setting, with a book called Try This at Home. For me, it's an opportunity to bridge the gap between at home trial and error activities (like baby Elliott trying to get the hammer in the right position to whack the pegs), exploration of easily observed natural phenomena (like little Bethany trying to get all the trees to stay that nice dark wet color), and the science fair-y explorations of middle schoolers.

What SHOULD kids try at home? As you can imagine, my view on this is somewhat idiosyncratic. I take a somewhat Montessori approach to young childhood, because I see the power of play-as-work to help a child figure out how the world works through her own experience. An hour of play at the sink is worth five books on the subject of splashing -- but a book on splashing has the power to inspire that play.

And so, I hit the books and the internet and some friendly scientists and teachers and parents to find ways to inspire kids to play and observe and notice things for themselves. It's going to be messy. We're going to be using a lot of food coloring, because it helps you see what's happening when, for example, a rose pulls water from a vase, or salt water separates from fresh, or water beads absorb 300 times their weight. There will be explosions and bubbles and foam and broken eggs and jelly bones.

May heaven help me, I have to supply and set up all 50 experiments and activities

so they can be photographed in my kitchen or here in the barn or outside in the yard. Before this happens, I have to make sure all the experiments and projects meet expectations, so I'm trying them at home myself. I'm stocking up on baby food jars, rubber gloves, Ivory soap, batteries and magnets. I'm making a big mess and learning things I didn't expect about the world. Best of all, I'm going to invite the kids -- and grandkid -- over to play with science with me.

Published on June 12, 2013 03:00

June 11, 2013

Who Made That?

It's been stressful around here for several weeks, so I was looking for some sort of mental relief. Then along came the New York Times Magazine on Sunday with the cover story: Who Made That? For those who haven't seen it, it's an A to Z collection of brief essays on the origin of a good number of common objects. Things like the band aid, Bunsen burner, diet soda, white lab coat, and the breath mint are covered (though why they included Rachel Maddow in the mix escapes me. Not that there's anything wrong with that).

So I opened the magazine and started reading. And almost immediately started to smile. It's loaded with interesting, odd, startling, funny details and hard to put down if you get a kick out of this sort of (not always serious) details.

Such as:

Did you know that the longest single zip-line is in Sacred Valley, Peru, and is 6,990 feet long. As the Scooter used to say, "Holy Cow!" The longest combined zip-line is in Georgia and measures 48,000 feet!

Or that:

Doris Richards founded the first dog park in 1979 in Berkeley, CA, in a space that seems to have had a good number of 'No Dogs' signs posted before she and her friends took it over.

Or that:

"Nero married a man in a public ceremony and accorded him the honors of an empress." Now that was something my textbooks seemed to have overlooked.

Or that:

Before 1968, every lacrosse stick was fashioned by Native Americans and took almost a year to make: "40-year-old hickory shafts had to be cured for months before being steamed, bent and carved."

It occurred to me while going through this list that coming across these details was one of the reasons I love to read nonfiction and do research; to come across some little known fact that grabs my attention and might grab the attention of readers. It's these bizarre little nuggets that can humanize someone I'm writing about or provide a moment of lightness in an otherwise grim story. And sometimes there is a connection with information that brings back a flash of a personal experience.

While reading about Brunch, I suddenly found myself recalling a day back in the early 1950s when my friend, Paul, and I were walking from my house to his. We were about six and the walk was about a mile distance, which we did unaccompanied. Along the way we decided to get his mother to make us something to eat, but wondered what we should ask for. It was 10:30AM, so it was too late for breakfast and too early for lunch. We then started playing with all sorts of combinations of the words (BreLunch, BreakLunch, BerLun, BreakUn and other even sillier ones) and speculating on what sort of food would be appropriate. We were nearly to his house when we hit on the word Brunch.

We stopped in our tracks when the word was spoken and looked at each other. It was so right we whooped and sprinted all the way to his house to let his mother know that we were geniuses and had just invented a whole new food category. We would be famous, we told each other. We would open a Brunch only restaurant (which we intended to call BrunchTime) and get rich.

Of course, when we announced we wanted Brunch, Paul's mom just smiled and said sure, as if the word Brunch was old news. Then she asked what we wanted and we asked for the only menu item we'd had a chance to think up: A peanut butter and jelly, bacon and fried egg sandwich on toasted Wonder Bread. With sliced dill pickle. Now that got her attention!

If you haven't read this Sunday's Times Magazine, you might want to take a few minutes and wonder down its aisle of invention. Even if you don't find a personal connection to any of them, at least you'll come away kinowing what a Brannock Device is. Have a safe and happy summer everyone. And I.N.K. on!

Published on June 11, 2013 00:30

June 6, 2013

Personal History

This month, each of us I.N.K. bloggers is supposed to write our last original post for the 2012-2013 school year, followed by a rerun of one of our favorite blogs in July and then a month off in August. But forgive me if I break protocol. Try as I might, I can't seem to write something original this month. My dad passed away on May 5, 2013, at age 93, and I'm still adjusting to the world without him in it. He was a wonderful father and a terrific role model who instilled in me a spirit of independence, a sense of humor, a love of sports, and a steadfast integrity in work and life. I had decided to run this post from December 2009 as my "best of" next month, but I offer it now, in his memory.

My dad will be 90 years old on December 8. To celebrate, we’re having a big party this Sunday, commemorating the milestone with excellent food, good cheer, and even a surprise or two. My brother, a one-time stand-up comedian, will be master of ceremonies at the festivities. Not surprisingly, my contribution will be providing the historical context.

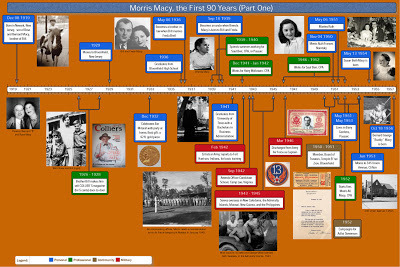

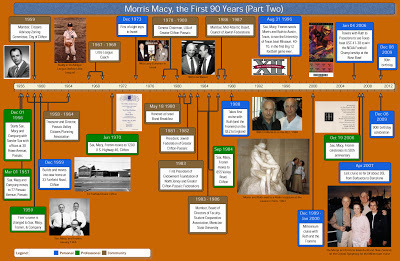

A few years ago, for my parents’ 50th anniversary, I created mini-magazines with pictures, short articles, and even a few puzzles about their life together—no doubt a reflection of my many years as an editor of Scholastic’s classroom magazines. This time, having just completed the back matter for an upcoming book, I decided to apply one of the go-to standards of nonfiction back matter to my dad’s life—the timeline.

Since I wanted this timeline to make a visual statement as well as an emotional one, I started by searching for software that would enable me both to organize events and import pictures. I found a few different programs, designed for business presentation purposes but adaptable for personal use. I took the plunge and bought one, then started working on the content. It turns out that despite knowing my dad for 55 years, I could not pinpoint as many defining moments and turning points as I thought. So I doggedly pursued the details of his life as I had those of Annie Oakley and Nellie Bly before him, poring over scrapbooks and photo albums and turning every visit to my parents’ home into an oral history session.

I learned volumes. For instance, my dad, who helped found one of the biggest accounting firms in New Jersey, got his start in business at age seven, when his older brother “forced” him to sell copies of Collier’s magazine for five cents door-to-door. He turned 13 in the midst of the Great Depression, so he celebrated his Bar Mitzvah with a party at home; he said his best gift was a $2½ gold piece. (Who even knew there was such a thing?) In the 1950s, both of my parents campaigned for Adlai Stevenson; they’ve got a letter signed by Stevenson thanking them for their support and a souvenir ticket to one of his rallies. Later in the decade, my dad continued his commitment to civic affairs by serving on the Citizens Advisory Zoning Committee in our town and the Citizens Planning Association for the area.

When I write biographies, I start with a subject who had an impact on society and use every available resource to try and learn more about who that person was. Working on my dad’s timeline, I went in the opposite direction. For most of my life, I’ve seen my dad from the context of our family, from my particular perspective as his older child, his only daughter. But looking at his accomplishments all mapped out on a colorful timeline helped me get a clear sense of his place in the world beyond our front door. What a great learning experience. What a great man.

Click on the timelines to see larger images.

Published on June 06, 2013 21:30

Keeping the Faith

<!--

/* Font Definitions */

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0;

mso-font-charset:128;

mso-generic-font-family:roman;

mso-font-format:other;

mso-font-pitch:fixed;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0;

mso-font-charset:128;

mso-generic-font-family:roman;

mso-font-format:other;

mso-font-pitch:fixed;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

/* Style Definitions */

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal

{mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:"";

margin:0in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

.MsoChpDefault

{mso-style-type:export-only;

mso-default-props:yes;

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

@page WordSection1

{size:8.5in 11.0in;

margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in;

mso-header-margin:.5in;

mso-footer-margin:.5in;

mso-paper-source:0;}

div.WordSection1

{page:WordSection1;}

</style> <br />

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">When you're working on a biography, what can you do when facts are sparse about an aspect

or a period of your subject’s life? <a href="http://deborahheiligman.com/" target="_blank">Deborah Heiligman</a>, <a href="http://www.susankuklin.com/" target="_blank">Susan Kuklin</a>, and I hoped for some answers to this question when we attended a panel called "Dealing with Black Holes in Your Narrative" at the </span><span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Compleat Biographer’s Conference a few weeks ago in New York. Deb shared some helpful nuggets from this panel in her <a href="http://inkrethink.blogspot.com/2013/0..." target="_blank">latest INK</a> column. (Thanks, Deb!)</span><br />

<br />

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">I keep thinking about what one of the panelists, an award-winning and esteemed biographer, said he <i>won’t</i> do in such a case. He won’t speculate on what someone

was thinking or feeling or doing. He eschews phrases such as “may have” or “could have”

or “must have felt.” He abstains from “perhaps” and “maybe.” He

believes these expressions can reduce a book’s credibility and energy level.</span></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<br /></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">An

audience member asked this panelist whether he thought it was ever OK to use

them. Surely the spare, occasional use of "she may have thought..." or "perhaps he felt..."—set against a

background of facts, of course—was acceptable? she asked hopefully. No, never, not to him. He

replied that even this can undermine a reader's faith in a book. Panelist 2 agreed with him. Case closed. </span></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<br /></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Except that it wasn't. Panelist 3, who is also an award-winning and esteemed biographer, eventually piped up. She pointed out that a writer is, after all, an interpreter

of a subject’s life. As long as the facts are firm, she said, then in

her view it’s fine for the biographer to wonder occasionally about a person's feelings or thoughts. You can present

the evidence you have, she said, and leave it as a question.</span><br />

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";"><br /></span>

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Several audience members nodded in agreement with her. I was one of them. But I recently saw a reader review of <span style="background-color: white;"><a href="http://marfebooks.com/master-georges-..." target="_blank"><i><span style="color: purple;">Master George's People</span> </i></a></span>on amazon.com that made me reexamine my position. The reviewer faulted the book for what she called </span>"no-source opinion statements, like 'the enslaved people no doubt saw the matter differently' and 'they felt.'" I know for sure what <i>I felt</i> when I read this criticism, and it was a brief moment of panic. Panelist number 1's words echoed in my head. My word choice had undermined at least one reader's faith in my book.<br />

<br />

But then I reminded myself that I would not have taken an unfounded, no-source leap. I grabbed the book and turned to the example the reviewer quoted. It's from chapter 4, "Resistance and Control." Here's the complete paragraph:<br />

<br />

<span style="font-size: x-small;"><span style="font-family: "Courier New",Courier,monospace;">Most of all Washington deplored the "spirit of thieving and housebreaking...among my people." He believed he fed, clothed, and housed his "people" as well as or better than any other slave owner in the region. As far as he was concerned, they were entitled to nothing more. From the slaves' point of view, however, what they were given by their master was totally inadequate. So they took it upon themselves to make up the difference. Meat disappeared from the meat house and corn vanished from the corn loft, as did cherries from the orchards and nails from construction sites. "I cannot conceive how it is possible that 6000 twelve penny nails could be used in the corn house at River Plantation," Washington fumed. <u>To him, these were acts of theft, pure and simple. Mount Vernon's enslaved people no doubt saw the matter differently. They felt they had earned a share of the goods their labor had produced."</u></span></span><br />

<br />

I went back to my annotated copy of the manuscript to check my source notes. To my surprise, the paragraph ended with "...Washington fumed." The last 3 sentences weren't there. Then I realized I must have added them later, at the suggestion of one of the two historians who vetted the manuscript for me. (One is a research historian at Mount Vernon who specializes in slave life, the other, a university professor, is a leading authority on African American colonial history.) I searched through my correspondence, and sure enough, I came across a note from one of them saying that I needed to add something about how the slaves felt about helping themselves to the fruits of their labor. Leaving the last word with Washington left the story one-sided. The other historian agreed.<br />

<br />

As far as we know, Washington's slaves left no written accounts. Very few of them could read or write. So it's true that we can't know exactly how they felt about their activities. But there are primary sources revealing how enslaved African Americans on other plantations viewed taking things, food in particular, from their owner, and a common theme was that "the result of labor belongs of right to the laborer."<br />

<br />

My framework of facts was firm, so I feel very comfortable with my decision to suggest how Washington's slaves would have felt about snatching chickens or sneaking cherries, to indicate that these activities did not compromise their moral code. Indeed, I think I would have been negligent not to have done so, unfaithful to those whose story I'm telling.<br />

<br />

Should biographers absolutely stay away from speculating about a subject's thoughts and feelings? Or is it acceptable to suggest occasionally how a subject might have felt or thought, as long as this is set against a strong background of facts? I'd love to know what other writers and readers think about this.<br />

<br /></div><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/blogsp..." height="1" width="1"/>

/* Font Definitions */

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0;

mso-font-charset:128;

mso-generic-font-family:roman;

mso-font-format:other;

mso-font-pitch:fixed;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0;

mso-font-charset:128;

mso-generic-font-family:roman;

mso-font-format:other;

mso-font-pitch:fixed;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

/* Style Definitions */

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal

{mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:"";

margin:0in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

.MsoChpDefault

{mso-style-type:export-only;

mso-default-props:yes;

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

@page WordSection1

{size:8.5in 11.0in;

margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in;

mso-header-margin:.5in;

mso-footer-margin:.5in;

mso-paper-source:0;}

div.WordSection1

{page:WordSection1;}

</style> <br />

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">When you're working on a biography, what can you do when facts are sparse about an aspect

or a period of your subject’s life? <a href="http://deborahheiligman.com/" target="_blank">Deborah Heiligman</a>, <a href="http://www.susankuklin.com/" target="_blank">Susan Kuklin</a>, and I hoped for some answers to this question when we attended a panel called "Dealing with Black Holes in Your Narrative" at the </span><span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Compleat Biographer’s Conference a few weeks ago in New York. Deb shared some helpful nuggets from this panel in her <a href="http://inkrethink.blogspot.com/2013/0..." target="_blank">latest INK</a> column. (Thanks, Deb!)</span><br />

<br />

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">I keep thinking about what one of the panelists, an award-winning and esteemed biographer, said he <i>won’t</i> do in such a case. He won’t speculate on what someone

was thinking or feeling or doing. He eschews phrases such as “may have” or “could have”

or “must have felt.” He abstains from “perhaps” and “maybe.” He

believes these expressions can reduce a book’s credibility and energy level.</span></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<br /></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">An

audience member asked this panelist whether he thought it was ever OK to use

them. Surely the spare, occasional use of "she may have thought..." or "perhaps he felt..."—set against a

background of facts, of course—was acceptable? she asked hopefully. No, never, not to him. He

replied that even this can undermine a reader's faith in a book. Panelist 2 agreed with him. Case closed. </span></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<br /></div>

<div class="MsoNormal">

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Except that it wasn't. Panelist 3, who is also an award-winning and esteemed biographer, eventually piped up. She pointed out that a writer is, after all, an interpreter

of a subject’s life. As long as the facts are firm, she said, then in

her view it’s fine for the biographer to wonder occasionally about a person's feelings or thoughts. You can present

the evidence you have, she said, and leave it as a question.</span><br />

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";"><br /></span>

<span style="mso-fareast-font-family: "Times New Roman";">Several audience members nodded in agreement with her. I was one of them. But I recently saw a reader review of <span style="background-color: white;"><a href="http://marfebooks.com/master-georges-..." target="_blank"><i><span style="color: purple;">Master George's People</span> </i></a></span>on amazon.com that made me reexamine my position. The reviewer faulted the book for what she called </span>"no-source opinion statements, like 'the enslaved people no doubt saw the matter differently' and 'they felt.'" I know for sure what <i>I felt</i> when I read this criticism, and it was a brief moment of panic. Panelist number 1's words echoed in my head. My word choice had undermined at least one reader's faith in my book.<br />

<br />

But then I reminded myself that I would not have taken an unfounded, no-source leap. I grabbed the book and turned to the example the reviewer quoted. It's from chapter 4, "Resistance and Control." Here's the complete paragraph:<br />

<br />

<span style="font-size: x-small;"><span style="font-family: "Courier New",Courier,monospace;">Most of all Washington deplored the "spirit of thieving and housebreaking...among my people." He believed he fed, clothed, and housed his "people" as well as or better than any other slave owner in the region. As far as he was concerned, they were entitled to nothing more. From the slaves' point of view, however, what they were given by their master was totally inadequate. So they took it upon themselves to make up the difference. Meat disappeared from the meat house and corn vanished from the corn loft, as did cherries from the orchards and nails from construction sites. "I cannot conceive how it is possible that 6000 twelve penny nails could be used in the corn house at River Plantation," Washington fumed. <u>To him, these were acts of theft, pure and simple. Mount Vernon's enslaved people no doubt saw the matter differently. They felt they had earned a share of the goods their labor had produced."</u></span></span><br />

<br />

I went back to my annotated copy of the manuscript to check my source notes. To my surprise, the paragraph ended with "...Washington fumed." The last 3 sentences weren't there. Then I realized I must have added them later, at the suggestion of one of the two historians who vetted the manuscript for me. (One is a research historian at Mount Vernon who specializes in slave life, the other, a university professor, is a leading authority on African American colonial history.) I searched through my correspondence, and sure enough, I came across a note from one of them saying that I needed to add something about how the slaves felt about helping themselves to the fruits of their labor. Leaving the last word with Washington left the story one-sided. The other historian agreed.<br />

<br />

As far as we know, Washington's slaves left no written accounts. Very few of them could read or write. So it's true that we can't know exactly how they felt about their activities. But there are primary sources revealing how enslaved African Americans on other plantations viewed taking things, food in particular, from their owner, and a common theme was that "the result of labor belongs of right to the laborer."<br />

<br />

My framework of facts was firm, so I feel very comfortable with my decision to suggest how Washington's slaves would have felt about snatching chickens or sneaking cherries, to indicate that these activities did not compromise their moral code. Indeed, I think I would have been negligent not to have done so, unfaithful to those whose story I'm telling.<br />

<br />

Should biographers absolutely stay away from speculating about a subject's thoughts and feelings? Or is it acceptable to suggest occasionally how a subject might have felt or thought, as long as this is set against a strong background of facts? I'd love to know what other writers and readers think about this.<br />

<br /></div><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/blogsp..." height="1" width="1"/>

Published on June 06, 2013 00:00

June 4, 2013

Assessing the Assessors: A Challenge to CETE

Recently

I received an email from a “passage writer” at the Center for Educational

Testing and Evaluation (CETE) in Lawrence KS offering me $500

to write passages for the assessment tests. Instead of excerpting my books,

which they’ve been doing for years, they are now asking me to create new

material. Maybe it’s because I’ve upped my price for the excerpts. Many years

ago, I didn’t charge very much. After all, it was just two or three

paragraphs written in prior years that would appear on an exam. Back then, I

didn’t notice that the number of children who would be reading my work would be

in the tens of thousands. In recent years, I’ve wised up and charged

considerably more for this limited use of a piece of my work, as have many other nonfiction authors. I guess the test creators felt reasonably confident that relatively few test

takers (children) have encountered our books in their classroom work, so the material would be new to them. Schools

supply children with committee-generated reading material (i.e. textbooks),

complete with worksheets, teachers’ guides, study questions, controlled

vocabulary and reading levels. The writing is pedestrian at best and

downright insulting to the reader at worst. I’ll wager that not a single

kid picks up one of these books out of curiosity or to read for pleasure.

Meanwhile,

our body of children’s nonfiction literature is waiting on library shelves on

the very same subjects that are in the curriculum. Since these books do

not have a captive audience, the authors write to captivate. The books

are designed to inspire and entertain as well as inform readers about the real

world. One reason why these books are so good is that authors are writing

material that they each feel passionate about and they have the freedom to use

many of the same literary devices fiction writer use, humor, satire, poetry,

and personal idiosyncrasies that give the works “voice.” The books are

beautifully illustrated and designed, a treat for the eye as well as the mind.

The freedom for self-expression in nonfiction has been hard-won by many of

these authors over the years. I, personally, have fought numerous battles

with editors for playful language, activities integrated into the text, art

that is woven into a description instead of using a disconnected caption,

and insertion of humorous asides.

Many years ago, I was asked to write a science text book. I was given an

outline and writing guidelines that made me feel strangled. Although I

needed the money, I turned it down. “I don’t write like this,” I told

them. “You could give an outline to Shakespeare and you might get

something you’d like to publish but you wouldn't get Shakespeare.”

(Not that I’m Shakespeare, but I think you get my point.) Another example

is fellow I.N.K. blogger, Steve Sheinkin, who wrote history textbooks

for years until he couldn’t stand it any more. His most recent book, Bomb! The Race to Build-and Steal-the World’s Most Deadliest

Weapon , was a National Book Award Finalist, and won the Sibert,

Newbery, and YALSA awards. So you can imagine how thrilled we authors are

that the CCSS require that our kinds of books are finally to be included in

literacy across the disciplines in elementary and high school classrooms. Our

step-child genre is emerging into the spotlight.

Not so

fast, say the test-makers. Maybe the price for excerpts from

excellent books by established authors has become too high, hence the offer to

commission new passages. But the kicker to the soliciting email was that

there were two attachments: “Tips for Writing Topics” and “Writing Guidelines.”

Here’s an excerpt:

“Topic

ideas should not be too broad. Proposed topic ideas should be given in detail,

in one to two full paragraphs.

“When

coming up with topic ideas for reading passages, it's always best to go with

something familiar to you. Choose topics in which you have prior knowledge or

interest. This will make the passage easier to write, and will often reflect in

the writing. Because writers may use a maximum of 5 sources when writing a

passage, choosing passages in your realm of knowledge will also minimize the

number of sources you have to rely on.

“Keep in

mind that passages may not have references to drugs, sex, alcohol, gambling,

magic, holidays, religion, violence, or evolution, and that topic ideas should

not lend themselves to passages which would require such content.”

And

“Use

grade-appropriate vocabulary. To check your passage, use Microsoft

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level readability test (part of Microsoft Word programs).”

Clearly

the authors of these documents didn’t know who they were writing for. Did

they think that after 90 books I need their tips? Do they have

any idea how these “tips” flatten text and clip the wings of a talented writer?

Don’t they have any consideration for the reader when they write?

Is it their intention that education is supposed to teach students how to read

bad writing?

The good

intentions of the Common Core Standards are being hijacked by the test

makers. Suddenly CETE is setting itself up as an arbiter of the quality

of nonfiction children are supposed to comprehend and think about

critically. So here’s my challenge to them:

Why don’t you let us authors take your standardized tests under the

same conditions that you give to children? Give us the time limits and

the pacing proctors. We can even try and do them cold without test prep.

If we flunk, what would that tell you? If we aced them what would that

mean? I have no idea how we’d do. I can provide at least two dozen top

nonfiction authors in all disciplines and more if you need a significant

sample. I can promise we’ll do our best and that none of your proctors

would have to follow your instructions for putting test papers with

vomit on them into plastic bags. Are you game? Whadya think?

I received an email from a “passage writer” at the Center for Educational

Testing and Evaluation (CETE) in Lawrence KS offering me $500

to write passages for the assessment tests. Instead of excerpting my books,

which they’ve been doing for years, they are now asking me to create new

material. Maybe it’s because I’ve upped my price for the excerpts. Many years

ago, I didn’t charge very much. After all, it was just two or three

paragraphs written in prior years that would appear on an exam. Back then, I

didn’t notice that the number of children who would be reading my work would be

in the tens of thousands. In recent years, I’ve wised up and charged

considerably more for this limited use of a piece of my work, as have many other nonfiction authors. I guess the test creators felt reasonably confident that relatively few test

takers (children) have encountered our books in their classroom work, so the material would be new to them. Schools

supply children with committee-generated reading material (i.e. textbooks),

complete with worksheets, teachers’ guides, study questions, controlled

vocabulary and reading levels. The writing is pedestrian at best and

downright insulting to the reader at worst. I’ll wager that not a single

kid picks up one of these books out of curiosity or to read for pleasure.

Meanwhile,

our body of children’s nonfiction literature is waiting on library shelves on

the very same subjects that are in the curriculum. Since these books do

not have a captive audience, the authors write to captivate. The books

are designed to inspire and entertain as well as inform readers about the real

world. One reason why these books are so good is that authors are writing

material that they each feel passionate about and they have the freedom to use

many of the same literary devices fiction writer use, humor, satire, poetry,

and personal idiosyncrasies that give the works “voice.” The books are

beautifully illustrated and designed, a treat for the eye as well as the mind.

The freedom for self-expression in nonfiction has been hard-won by many of

these authors over the years. I, personally, have fought numerous battles

with editors for playful language, activities integrated into the text, art

that is woven into a description instead of using a disconnected caption,

and insertion of humorous asides.

Many years ago, I was asked to write a science text book. I was given an

outline and writing guidelines that made me feel strangled. Although I

needed the money, I turned it down. “I don’t write like this,” I told

them. “You could give an outline to Shakespeare and you might get

something you’d like to publish but you wouldn't get Shakespeare.”

(Not that I’m Shakespeare, but I think you get my point.) Another example

is fellow I.N.K. blogger, Steve Sheinkin, who wrote history textbooks

for years until he couldn’t stand it any more. His most recent book, Bomb! The Race to Build-and Steal-the World’s Most Deadliest

Weapon , was a National Book Award Finalist, and won the Sibert,

Newbery, and YALSA awards. So you can imagine how thrilled we authors are

that the CCSS require that our kinds of books are finally to be included in

literacy across the disciplines in elementary and high school classrooms. Our

step-child genre is emerging into the spotlight.

Not so

fast, say the test-makers. Maybe the price for excerpts from

excellent books by established authors has become too high, hence the offer to

commission new passages. But the kicker to the soliciting email was that

there were two attachments: “Tips for Writing Topics” and “Writing Guidelines.”

Here’s an excerpt:

“Topic

ideas should not be too broad. Proposed topic ideas should be given in detail,

in one to two full paragraphs.

“When

coming up with topic ideas for reading passages, it's always best to go with

something familiar to you. Choose topics in which you have prior knowledge or

interest. This will make the passage easier to write, and will often reflect in

the writing. Because writers may use a maximum of 5 sources when writing a

passage, choosing passages in your realm of knowledge will also minimize the

number of sources you have to rely on.

“Keep in

mind that passages may not have references to drugs, sex, alcohol, gambling,

magic, holidays, religion, violence, or evolution, and that topic ideas should

not lend themselves to passages which would require such content.”

And

“Use

grade-appropriate vocabulary. To check your passage, use Microsoft

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level readability test (part of Microsoft Word programs).”

Clearly

the authors of these documents didn’t know who they were writing for. Did

they think that after 90 books I need their tips? Do they have

any idea how these “tips” flatten text and clip the wings of a talented writer?

Don’t they have any consideration for the reader when they write?

Is it their intention that education is supposed to teach students how to read

bad writing?

The good

intentions of the Common Core Standards are being hijacked by the test

makers. Suddenly CETE is setting itself up as an arbiter of the quality

of nonfiction children are supposed to comprehend and think about

critically. So here’s my challenge to them:

Why don’t you let us authors take your standardized tests under the

same conditions that you give to children? Give us the time limits and

the pacing proctors. We can even try and do them cold without test prep.

If we flunk, what would that tell you? If we aced them what would that

mean? I have no idea how we’d do. I can provide at least two dozen top

nonfiction authors in all disciplines and more if you need a significant

sample. I can promise we’ll do our best and that none of your proctors

would have to follow your instructions for putting test papers with

vomit on them into plastic bags. Are you game? Whadya think?

Published on June 04, 2013 21:30

June 3, 2013

WHAT KIDS CAN DO

This weekend I got a truly amazing package in the mail. It

was jam-packed with 20 stories written by third graders, and they weren’t just

any old stories either. Each one was eye-popping,

unique, full of surprises, AND 100% TRUE; in short, the type of tales kids can hold onto for the rest of their lives. So

what’s the story behind these stories?

Back in the end of March, I did a live video conference with these

budding authors via a Library of Congress grant. Designed to get kids excited about using primary

source material, the grant is linked directly to the CCSS.

As an example of the incredible stories you can uncover by

exploring such sources, we had a wonderful time exploring the action-packed journals

of Lewis and Clark from one of my books and also figuring out what other primary source material I used to make the pictures as accurate (and as much

fun) as possible.

After that, we discussed several cool ways kids can write

their own nonfiction stories by using primary sources, and one of my suggestions was for each kid to

interview an older member of their family about their own adventures a

long time ago. We talked about methods

news reporters use to ask hard questions, not just easy ones. (I said that

their families would love to be interviewed this way.) And I introduced them to my infamous “meat

and salt” method of writing non-fiction, in which the meat = the facts (names,

dates, places, etc.) and the salt = all the unusual or surprising or funny big

and little things that bring a story to life and make you want to read more.

These are some very lucky kids. They happen to have an outstanding Pennsylvania teacher

named Amy Musone, and after our talk, she decided that the family interviews

were worth pursuing. With Skype support from

Sue Sheffer, a retired teacher working with Amy and her class via a grant from the Library of Congress, the kids got on a roll and started brainstorming. They decided

which family members they wanted to interview and why, and each student focused on a particular time in that person’s life.

The results knocked everyone’s socks off, including Amy’s. So

at the end of May, their school held a big after-school Celebration of Family

Stories, replete with refreshments no less.

Family members from all over came to hear the students read their tales,

and they laughed, cried and were simply captivated.

Every story is compelling, to say the least. There are tales about bombing Nagasaki, playing the ancient game of

Pac Man, taking knitting classes in Ecuadorian schools, blowing up an abandoned

building with a tank, scrubbing floors in Marine barracks with a toothbrush and

saluting every time you wanted a drink of water, and what life is like without

technology. It’s impossible to know

which story to put first, but here are a few tiny abridged excerpts written by third

graders in their own words—mere hints about the whole shebang. Check 'em out:

ADVENTURES

“dad was such a dare devil that he went car surfing with his

friends. His friend tried to throw him off!, but my dad was good at staying

on. He only fell off a couple of times! ...my

dad thinks cliff jumping is the most fun stunt because he loves the rush of

falling through the air!” (the author includes

lots more stunts his dad’s mom didn’t know about plus a photo of Christopher

Reeve as Superman.)

“My brave, amazing Uncle was in the Army….he and his team

had to go through this confidence course….there was a building that was 40’

tall and they had to repel down the building.

The 40’ tall building would sway.

My Uncle said this was the most scariest time for him in the Army….[now]

My Uncle is looking forward to becoming a Fire Chief. [He] is a wonderful Uncle

because he risks hi life for others and everyday helps somebody that needs

help.”

SOME COOL GROSS STUFF

“During the first year of medical school, my mom had to

dissect a human body. It was a smelly

task and after they were done for the day, they would be smelly too. Something that she thought was pretty funny

was the comments that people would say and the funny faces they would make when

they would smell the anatomy students.”

AND LOTS OF HISTORY

“When my Great Grandma was a little girl…she felt sad

because when a white person threw a rock at a black person, a black person

couldn’t throw a rock back…..She went to the March on Washington in 1963. The

Civil Rights Leaders talked about how it wasn’t right how African Americans

were being treated. In the South, police

had dogs bite African Americans….”

“There was the time in China when all people no matter you

are men, women, or kids, would wear blue shirts and pants. My dad was born

during this time in 1978 with no brothers or sisters…..at that time there were

not much toys so they would go out and play in the nature. My dad and his friend would catch tadpoles

and watch them grow up…They…would feed their tadpoles leftover rice….He didn’t

have any black and white TV until he was 10.

He had his first small single door refrigerator at 12 years old.”

“Back in the year 1904, the war between Russia and Japan

began. In addition my great great great grandpa

was born. Even though he lived in Russia

he didn’t like it very much. There was a

massive war going on. This meant that

once he was old enough, he would be forced to be in the Russian army…It was

then that he decided to save enough money to buy a ticket and move to the

United States…..” (and his further adventures once he arrived) “I hope that one

day I will follow in the footsteps of my great great great grandpa and be as

courageous as [he] was (except that I’d like to play football too)."

“My grandma just turned 79 years old. Abuela used to sow

tobacco plants on the farm she grew up on….Abuela’s ancestors are a mix of

African slaves, Spaniards from Spain and Taino Indians, the first inhabitants

of Puerto Rico. Abuela’s education lasted only until the 4th grade

because Abuela had to work on the farm... They traveled on horseback…and there

was no technology….it was a beautiful place, surrounded by palm trees,

mountainsides and the songs of frogs.” And this: “Back when my grandma was a child all she was

allowed to wear were dresses and skirts, no pants or shorts which sounds TERRIBLE

to me.”

You gotta love these kids (and their school too), right? Now every one of them is an author, a researcher, an historian, and an open-minded, creative thinker who's learning to use his or her noggin to uncover the facts.

Published on June 03, 2013 21:00