Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 27

May 16, 2013

Reminding Myself

I have been traveling much more than usual of late. Travel always sparks new ideas. Perhaps it is because it is spring, or because I’ve been to Italy and Texas and Little Cranberry Isle and back, but my brain is bursting with new ideas. I am always reminded, when I get outside of my own mini-microcosm, how many ways there are to live in this wide world. How many different perspectives, situations, surroundings, events—all shaping the larger cultures, and the smaller ones within. And how many interesting people there are--everywhere!

I remind myself to stop and be grateful. Grateful for all these things, and grateful I had parents and teachers and the rest of the village to remind me to look around and be AWAKE.

It is a marvel, really. A miracle. All of these fascinating things just beyond our own fingertips. Every day brings some new observation, if you’re looking. We talk about research, writing, and revision often, and those topics feel comfortable, like a well-worn pair of work gloves. But it’s the wonder that stops me in my tracks. Those moments when I allow myself to see the world through my own child inside, who is not imposing too much knowledge or point of view on the world. That is when I get my best ideas.

This is a lesson I will remind myself to hold close when I talk with children about writing nonfiction. Or perhaps, I will let them teach me. They are the best at it, after all.

I remind myself to stop and be grateful. Grateful for all these things, and grateful I had parents and teachers and the rest of the village to remind me to look around and be AWAKE.

It is a marvel, really. A miracle. All of these fascinating things just beyond our own fingertips. Every day brings some new observation, if you’re looking. We talk about research, writing, and revision often, and those topics feel comfortable, like a well-worn pair of work gloves. But it’s the wonder that stops me in my tracks. Those moments when I allow myself to see the world through my own child inside, who is not imposing too much knowledge or point of view on the world. That is when I get my best ideas.

This is a lesson I will remind myself to hold close when I talk with children about writing nonfiction. Or perhaps, I will let them teach me. They are the best at it, after all.

Published on May 16, 2013 05:46

May 14, 2013

Good Review / Bad Review

If you write a book, you will most likely get reviewed. Like it or not. Some reviews are perfectly nice; some not so nice. And then there are those reviews which seem to be lazy repeats of the front jacket copy, but that's another story.

I read all the reviews that I get to see (my first book had well over 200 reviews, every one of them carefully clipped out and mailed to me by my publisher; I saw [maybe] ten reviews of my last book, all via e-mail!). Because I always blame myself for falling short, I study every line of the reviews, trying to figure out how to make future books better. I was thinking about my process with reviews a few weeks back and how both the good and bad ones have helped me to re-evaluate and change how I write.

The Good Review: Way back in another time and dimension, I wrote a history of tractors (brilliantly titled -- wait for it -- TRACTORS: From Yesterday's Steam Wagons to Today's Turbocharged Giants, available as we speak at Amazon used books for $0.70). I may have told this story here before, so I'll make it brief. I was telling my Dad about this wonderful, innovative, amazing book about tractors I'd just revised and was ready to mail back to my publisher. After I stopped yammering, my Dad sat back, smiled knowingly, and said: "Jimmy, that'll be a big hit in Russia."

I thought that line was brilliant and laughed out loud. But later I started to wonder who, in their right mind, would actually want to pick up a book about tractors, let alone read it. Panic set in. The package with the manuscript was sitting on a table, very neatly wrapped and ready to go out. But I hesitated. I had to do something before the published book was banished to the far away remainder Gulogs, but what? Which is when I remembered that almost all of the early steam tractors blew up at some point or other, and that the inventors and on-lookers often wrote about these unexpected and exciting developments. I opened the package and spent the following days putting in quotes, many of them offbeat and funny (what's not to laugh about when a giant metal tank of steam explodes?). And guess what; it not only received very positive reviews, but School Library Journal gave it a star (and this was when starred reviews weren't very commonplace).

The thing about the SLJ review is that it mentioned the quotes. Not in any depth; more in passing briefly over what the book was about. I didn't think much of that little phrase until a few years later I began doing research on underage boys from both sides in the Civil War. As I gathered in more and more research, I began to wonder how I would present the information. Happily, I remembered the SLJ review for TRACTORS and decided to let these young soldiers tell their own stories, using pieces from their letters home, diaries, memoirs, and company histories to describe their enlistment, training, battle experience...in short, their stay in the army start to finish. This wealth of firsthand accounts also provided the book's subtitle. THE BOYS' WAR: Confederate and Union Soldiers Talk abop the Civil War received very nice reviews (and it didn't hurt that it was published the very same week that Ken Burns' Civil War documentary was first aired!).

The Bad Review: Okay, this should be 'reviews.' So I was able to have several nonfiction books published and the reviews were encouraging. But one review source, while saying very positive things about these books, also tacked on a brief complaint. They wanted citations for my various sources. Please remember that this was a very different time (the 1980s); most nonfiction books then, even the most serious, usually had a brief bibliography and little else. So when this review source said this, I was troubled and wondered what to do about it.

Here's a bit of publishing history. I'm sure there were people around back then who championed having more sources, but I never came across them. Not in person, that is. When I spoke to editors and other writers, just about everyone thought the idea of extensive notes and sources was a bit, how to say this, excessive. It would take up a decent amount of space in the book (which could be used to add text or illustrations) and would enough kids really use them to justify this? I know, this seems like a silly question now, but back then it was real and we were all trying to puzzle out what to do (or not do).

When the first negative review like this appeared, I had another book at the binder about to appear and another in galley pages (yes, it was a different era). I dithered a bit and both books were published sans notes and sources. And, yes, that review source criticized both titles for this lack of information.

What to do? I wondered. I had another manuscript ready to go off and I was wondering if I should ignore my colleagues and just put in the info. Which was when I happened to have dinner with a friend, Jim Giblin. We spoke about this emerging notes and sources situation (me feeling a bit put upon and undecided about what to do). Jim's response was characteristically practical. Why risk having a negative sentence or phrase soil an otherwise good review. Put the notes in!

Fine, I said. But most backmatter is a bunch of ids and ibids and such that even adults find boring and difficult to interpret. His answer: Have some fun with them.

Which is what I've tried to do ever since. I try to play with and change up the backmatter in every book, shaping it in a way that makes it not just possible for young readers to know where my information came from and how to access it, but easy and non-threatening as well. Every time I do backmatter, I learn new things about how to communicate this to the readers (a quest that will probably never end but keeps me on my toes and having some fun).

Good Review/Bad Review. Each kind is trying to tell me something besides whether the book works or not. Sometimes it takes a while for me to see exactly what it might be, but if I stay open to the reviewer's emotional response and hints, in time it'll register and lead me.

I read all the reviews that I get to see (my first book had well over 200 reviews, every one of them carefully clipped out and mailed to me by my publisher; I saw [maybe] ten reviews of my last book, all via e-mail!). Because I always blame myself for falling short, I study every line of the reviews, trying to figure out how to make future books better. I was thinking about my process with reviews a few weeks back and how both the good and bad ones have helped me to re-evaluate and change how I write.

The Good Review: Way back in another time and dimension, I wrote a history of tractors (brilliantly titled -- wait for it -- TRACTORS: From Yesterday's Steam Wagons to Today's Turbocharged Giants, available as we speak at Amazon used books for $0.70). I may have told this story here before, so I'll make it brief. I was telling my Dad about this wonderful, innovative, amazing book about tractors I'd just revised and was ready to mail back to my publisher. After I stopped yammering, my Dad sat back, smiled knowingly, and said: "Jimmy, that'll be a big hit in Russia."

I thought that line was brilliant and laughed out loud. But later I started to wonder who, in their right mind, would actually want to pick up a book about tractors, let alone read it. Panic set in. The package with the manuscript was sitting on a table, very neatly wrapped and ready to go out. But I hesitated. I had to do something before the published book was banished to the far away remainder Gulogs, but what? Which is when I remembered that almost all of the early steam tractors blew up at some point or other, and that the inventors and on-lookers often wrote about these unexpected and exciting developments. I opened the package and spent the following days putting in quotes, many of them offbeat and funny (what's not to laugh about when a giant metal tank of steam explodes?). And guess what; it not only received very positive reviews, but School Library Journal gave it a star (and this was when starred reviews weren't very commonplace).

The thing about the SLJ review is that it mentioned the quotes. Not in any depth; more in passing briefly over what the book was about. I didn't think much of that little phrase until a few years later I began doing research on underage boys from both sides in the Civil War. As I gathered in more and more research, I began to wonder how I would present the information. Happily, I remembered the SLJ review for TRACTORS and decided to let these young soldiers tell their own stories, using pieces from their letters home, diaries, memoirs, and company histories to describe their enlistment, training, battle experience...in short, their stay in the army start to finish. This wealth of firsthand accounts also provided the book's subtitle. THE BOYS' WAR: Confederate and Union Soldiers Talk abop the Civil War received very nice reviews (and it didn't hurt that it was published the very same week that Ken Burns' Civil War documentary was first aired!).

The Bad Review: Okay, this should be 'reviews.' So I was able to have several nonfiction books published and the reviews were encouraging. But one review source, while saying very positive things about these books, also tacked on a brief complaint. They wanted citations for my various sources. Please remember that this was a very different time (the 1980s); most nonfiction books then, even the most serious, usually had a brief bibliography and little else. So when this review source said this, I was troubled and wondered what to do about it.

Here's a bit of publishing history. I'm sure there were people around back then who championed having more sources, but I never came across them. Not in person, that is. When I spoke to editors and other writers, just about everyone thought the idea of extensive notes and sources was a bit, how to say this, excessive. It would take up a decent amount of space in the book (which could be used to add text or illustrations) and would enough kids really use them to justify this? I know, this seems like a silly question now, but back then it was real and we were all trying to puzzle out what to do (or not do).

When the first negative review like this appeared, I had another book at the binder about to appear and another in galley pages (yes, it was a different era). I dithered a bit and both books were published sans notes and sources. And, yes, that review source criticized both titles for this lack of information.

What to do? I wondered. I had another manuscript ready to go off and I was wondering if I should ignore my colleagues and just put in the info. Which was when I happened to have dinner with a friend, Jim Giblin. We spoke about this emerging notes and sources situation (me feeling a bit put upon and undecided about what to do). Jim's response was characteristically practical. Why risk having a negative sentence or phrase soil an otherwise good review. Put the notes in!

Fine, I said. But most backmatter is a bunch of ids and ibids and such that even adults find boring and difficult to interpret. His answer: Have some fun with them.

Which is what I've tried to do ever since. I try to play with and change up the backmatter in every book, shaping it in a way that makes it not just possible for young readers to know where my information came from and how to access it, but easy and non-threatening as well. Every time I do backmatter, I learn new things about how to communicate this to the readers (a quest that will probably never end but keeps me on my toes and having some fun).

Good Review/Bad Review. Each kind is trying to tell me something besides whether the book works or not. Sometimes it takes a while for me to see exactly what it might be, but if I stay open to the reviewer's emotional response and hints, in time it'll register and lead me.

Published on May 14, 2013 00:30

May 13, 2013

Happy Mother's Day

I was going to write about something entirely different

for this month’s blog but when I typed the first line on Sunday morning, out

came, Thanks, Mom.

Yesterday, of course, was Mother’s Day. At this point in my and my family’s life, I

am the mother who is celebrated with gorgeous flowers, chocolate (two of my

great pleasures) and, if I feel like it, an extracted promise to do some odious

chore.

My mom died in 2006, so she isn’t here to be included in gift

giving. Or phone calls, although we affectionately and impulsively tucked her

favorite, well-used red princess phone into her casket. She was a wonderful mom for many reasons. Given I.N.K.'s focus, I'd like to celebrate how she helped me become a writer just by being who she was.

We always had books in the house. We were always read to.

I had a lot of nightmares when I was a kid. So I slept with my door open and the hall

light on, which threw a swatch of light into my bedroom that was perfect for

sneak reading. Let’s just say, I took

advantage of it. I think my mom

knew. She never said a word, doubtlessly

realizing that forbidden fruit is always more delicious.

Once I had a pajama party, maybe in fourth grade, and late

into the night when we went into the kitchen for snacks, we found it had been

invaded by a stream of ants. Our squeals

brought Mom downstairs. I frankly can’t

remember if she dealt with the ants first—or, not at all. All I can see is the picture of my mom

standing in the kitchen in her nightgown, reading The World Book entry about ants to a bunch of girls waiting

for their Swanson’s chicken pot pies to come out of the oven. She always liked to look up things.

When she could afford it, she bought us/her an Encyclopedia Britannica.

A year or two later, I was enthralled by reading Gone

with the Wind. I got in trouble when

my

myteacher found that I was using my textbook as a shield to camouflage my open

copy. When Mom found out, she

laughed. But her favorite GWTW story was

when I burst into my parents’ bedroom a few nights later, waking her up with the

tearful accusation, “You didn’t tell me it was going to end like that.”

Fast forward--about two years after I got a master’s

degree in psychology that my parents paid for, tried it out and realized the

job wasn’t for me, I decided to become a writer. Somewhat arbitrarily. Then it was what Mom didn’t say that was

important. She didn’t say, you have

never shown much interest in writing before or how will you make money or is

this practical.

And when my first

article came out in the Sunday edition of the Boston Herald American, she called the paper to get a

dozen copies sent to her in Detroit. She wanted originals, not xeroxes. When my first book came out, she just might have put me in the royalty plus column all by herself.

Thanks, Mom.

Published on May 13, 2013 02:00

May 9, 2013

Balance

At critique group this week, four of us sat around a table,

crunching on nuts, sipping iced tea, and talking about balance. All four of us

work at home, which can be great for things like having a flexible schedule.

(Critique group meetings at 2 pm on Tuesdays? No problem.)

But working at home can have its drawbacks, as well—and

that’s where the conversation wound around to after the critiquing was done.

Working at home can be lonely. If I didn’t have a dog, there

might be days when I never left the house.

Working at home can be sedentary. If I didn’t get up for

snacks, I might hardly move at all.

Most of all, working at home can be non-stop, if you let it.

With no time card to punch, no daily commute defining the parameter of the

‘work day,’ you really could work all the time. Writer friends confess to me

all the time that they feel guilty taking time away from their desk to meet a

friend for lunch, take a walk in the park, go out with their husband for

coffee.

But they shouldn’t, and if you work at home, you shouldn’t,

either.

A story a few weeks ago on npr discussed several studies

done on keeping your brain healthy and your memory strong—two things that come

in handy when you’re a writer (or do anything else, for that matter.)

The studies looked at people over 80 and how they fared as

they aged. But the conclusions apply to us all, especially those of us who work

at home:

Physical exercise is key.

Social contact is essential.

And you need to leave your house and get out in the world,

on a regular basis.

So, while I could work all the time, taking the long view of

a productive career (not to mention a happy life) suggests that I shouldn’t—and

I shouldn’t feel guilty about it, either.

I just joined a gym class full of neighbors I’d like to get

to know.

I start today.

Published on May 09, 2013 01:00

May 8, 2013

When Facts Change...Again!

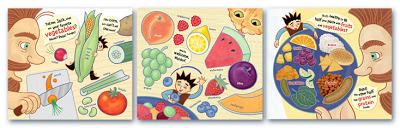

New information can be tough to swallow at times. I wrote previously on I.N.K. about my picture book based on the USDA Food Guide Pyramid that had to be updated due to a change in the graphic (see middle image, below). It happened again in 2011 when the MyPlate program was introduced. Actually, I prefer the plate graphic to the pyramids, which were visually awkward to work with.

My ever-alert editor at Holiday House, Mary Cash, sent me an email the day the news appeared in the New York Times. It was a surprise, but there's no sense crying over spilled milk, right? Obviously my 1994/2007 book The Edible Pyramid , which was set inside a pyramid-shaped restaurant, was instantly defunct. Or was it? More about that in a second.

A new approach was needed, so I began to noodle on it. For some reason, the idea of having big images of various foods with a small main character popped into mind. Have bugs as characters? Hmmm...obvious downsides to that. How about if the food is accidentally put into a machine that enlarges it...sounds implausible at best, or just plain dumb. Oh! I know who it's gonna be: that classic character Jack, who climbs up the beanstalk! So I wrote the story, yada yada, made a dummy, yada yada, digitally painted the illustrations, and yada yada, here it is:

Or will be, soon. It's technically a Fall title, but books have a way of getting around before their official birthday, you know? The story starts out like the traditional fairy tale, but instead of eating Jack, the giant cooks him a healthy meal. The giant, Waldorf, is definitely a good egg.

The book is designed to be a fun introduction to MyPlate and hopefully to a lifetime to healthy eating for kids. The goal for the illustrations was to show an abundance of fresh, appetizing foods, the best starting point for good meals. No processed factory foods here, except at the end under the Empty Calories section.

What about the leftovers, the existing copies of The Edible Pyramid? I was surprised to find out that some educators are still using the pyramid system, because the main difference is the presentation rather than the content. It can take awhile for some organizations to make the transition, apparently. So it's still selling, if not like hotcakes.

In any case, I'm looking forward to cooking up some activities to go with the book. Okay, I'll stop with the food and eating sayings now. Stick a fork in me, I'm done!

My ever-alert editor at Holiday House, Mary Cash, sent me an email the day the news appeared in the New York Times. It was a surprise, but there's no sense crying over spilled milk, right? Obviously my 1994/2007 book The Edible Pyramid , which was set inside a pyramid-shaped restaurant, was instantly defunct. Or was it? More about that in a second.

A new approach was needed, so I began to noodle on it. For some reason, the idea of having big images of various foods with a small main character popped into mind. Have bugs as characters? Hmmm...obvious downsides to that. How about if the food is accidentally put into a machine that enlarges it...sounds implausible at best, or just plain dumb. Oh! I know who it's gonna be: that classic character Jack, who climbs up the beanstalk! So I wrote the story, yada yada, made a dummy, yada yada, digitally painted the illustrations, and yada yada, here it is:

Or will be, soon. It's technically a Fall title, but books have a way of getting around before their official birthday, you know? The story starts out like the traditional fairy tale, but instead of eating Jack, the giant cooks him a healthy meal. The giant, Waldorf, is definitely a good egg.

The book is designed to be a fun introduction to MyPlate and hopefully to a lifetime to healthy eating for kids. The goal for the illustrations was to show an abundance of fresh, appetizing foods, the best starting point for good meals. No processed factory foods here, except at the end under the Empty Calories section.

What about the leftovers, the existing copies of The Edible Pyramid? I was surprised to find out that some educators are still using the pyramid system, because the main difference is the presentation rather than the content. It can take awhile for some organizations to make the transition, apparently. So it's still selling, if not like hotcakes.

In any case, I'm looking forward to cooking up some activities to go with the book. Okay, I'll stop with the food and eating sayings now. Stick a fork in me, I'm done!

Published on May 08, 2013 00:00

May 6, 2013

ARE WE HAVING ANY FUN YET? TEACHING TO THE TEST

So today (I’m writing on Monday) I was supposed to do a 9:00

AM test call for an upcoming video conference with some seventh graders. Lo and behold, at 8:30 AM, my screen lights

up and a harried-looking tech person appears amidst stacks of boxes. “Sorry,” she says, “but we have standardized

tests all day long today so I’m in a hurry.” Since our upcoming video conference is based on

a book I wrote about the Revolutionary War, I ask her if the students have

studied that period yet. “Not much,” she

says. “All we do in this state is test,

test, test, so the kids don’t learn a thing.”

Hmmmm….I think she was in such a hurry that she was accidentally

thinking out loud in front of a total stranger.

But she’s definitely not alone. I

hear this same complaint from teachers all the time when I visit schools.

Ever since the No

Child Left Behind Act first reared its head in 2002, kids in have had to take tons

of standardized tests, and if they don’t do well, their schools pay the piper. They stand to lose federal funding and free

tutoring and worse. These tests cover

a very narrow part of the curriculum, but they supposedly show whether kids are

learning or not, whether their teachers are any good, whether students have to

take even more mind-numbing skill-and-drill classes in summer school, and whether

they will stay awake long enough to pass to the next grade. Cheating is common—even

some teachers and principals cheat by upping the test scores because teachers

and principals can get fired or get a fat raise depending upon the results. Kids are bored to death or stress

out over these tests. And nobody is having any fun.

The worst part is

that so much invaluable class time is spent teaching to the tests at the

expense of every single thing that can get kids excited about learning. Who wants to sit in a chair all day long and study

from some dry-as-dust standardized test prep book just to keep their school out

of trouble? And as updated more “interesting”

tests get progressively harder, even more test prep is in the works.

Ahem. Ladies and

gentlemen, there are better ways to teach and there are better ways to learn. Why

would anyone want to give up creative hands-on activities or ignore great music

and art and foreign languages and amazing stories from history just so that

they can mark the right box on a test form?

Who want to cut out class trips, whether they’re to the school library

(to find some great nonfiction books, of course) or to some outstanding museums or to the great outdoors? What

is happening to young peoples’ health when physical education and even recess

give way to studying for the tests? What if a class wants to explore a certain

topic in depth? In many schools, plenty

of such worthwhile and beloved activities are on the chopping block.

Even the best

teachers have trouble raising test scores under certain conditions. In some

places kids can come to school hungry. Some neighborhoods are like revolving

doors where students come and go all the time. Plenty of parents are overworked

or jobless or have other problems that keep them from getting involved with

their kids’ education in any way. If students have recently moved here from

foreign countries and are not fluent in English, they will fare poorly on the

tests no matter how smart they are. But

the tests reflect none of this. They don’t

show a thing about individual student progress or whether kids can think

creatively or whether they have good critical thinking skills or whether they

love to learn.

But at least someone

is thinking creatively out there. I loved this article entitled Eighth

grader designs standardized test that slams standardized tests. Its your homework, so of course you have to read

it.

Published on May 06, 2013 21:00

Happy Birthday

I experienced another birthday recently

(celebrated is no longer appropriate; endured is over-dramatic, at least for

the time being). Without quantifying too much, let’s just say I can remember

Sputnik but not the Korean War.

Why bring it up? My life has,

coincidentally, been concurrent with the last half of the 20th century. Plus a

bit of the 21st. And this period has been a remarkable one for science. I 've

read persuasive arguments that for all the amazing advances in medicine,

communications, and transportation that the past 50 or 100 years have

witnessed, the greater paradigm shift happened during the industrial

revolution. The telegraph, the steam engine, and the transition from farm to

factory had a bigger impact on most peoples lives. This may be true, but our

understanding of the natural world wasn’t changing at the same rate. The

universe described by Newton in the 17th century was the same universe people

inhabited at the beginning of the 20th century. Since then, we’ve come light

years, literally.

One of the most commonly encountered

criticisms of a scientific world view is that science, as a tool for

understanding the world, is no more legitimate than almost any other

mythological or investigative methodology. On the left, this manifests itself

as relativism — the idea that there are no absolute truths, only truth relative

to some cultural or intellectual frame of reference. On the religious right,

science is sometimes positioned as an antagonist to Christianity or Islam, and

is often characterized as a religion itself, especially evolutionary theory. To

quote the Institute of Creation Research (I know, I spend too much time looking

at sites like this): “Evolutionism is thus intrinsically an atheistic

religion.”

I think much of the misunderstanding

about science has to do with a focus on conclusions rather than process. This

is partly a function of the way science and scientific ideas are reported in

popular media. When some finding — margarine is better for one’s heart than

butter — is accepted as dogma only to be discredited later, it appears that the

scientific method has failed. But

the fact that science can accommodate new information and change its

conclusions to provide a more accurate description of something is one of its

strengths. Science thrives on failure. This is in contrast to many of the

belief systems science now finds itself in conflict with, most of which have

not changed the explanations they offer (if any) for hundreds or thousands of

years.

So, back to that birthday. It’s offers a

good excuse to think about a few of the important scientific concepts that have

been accepted as mainstream science only during my lifetime. Many replaced

earlier theories that had to be discarded or completely revised.

An incomplete

list:

• By deciphering the structure and

mechanism of DNA in 1953, Watson and Crick explained the mechanism of heredity and

showed that life is digital, not analog.

• In 1964, Wilson and Penzias discovered

the cosmic background radiation, which allowed other scientists to confirm the

Big Bang as the universe’s origin and relegate the steady-state theory to the

dustbin of cosmology.

• Continental drift. What is obvious to a

second grader — the continents fit together like a jigsaw puzzle and must have

been connected at some point — was proposed by a few geologists but resisted by

most until the 1960s, when symmetrical magnetic anomalies on the seafloor

showed that the continents were separating along the mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Continental drift explained not only the shape and position of the continents

but the existence of many geological features, such as the Himalaya mountains

and the Marianas Trench.

• Until the 1970s, it was widely accepted

that all multi-cellular life on earth is dependent on the sun, either directly

or indirectly. In 1977, hydrothermal vents were discovered in the Pacific

Ocean. These “black smokers” are surrounded by ecosystems that get their energy

not from the sun but from dissolved chemicals in hot water emerging from the

vents.

• In 1980, Walter and Luis Alvarez

discovered a worldwide layer of the element Iridium in strata dating from the

end of the dinosaur era 65 million years ago. They proposed a large asteroid

impact as a key event in the extinction of the dinosaurs (and many other forms

of life), an idea that is widely accepted by earth scientists.

• A few scientists proposed the idea of

human-caused global warming as long ago as the 19th century, but it wasn’t

until the 1980s that an overwhelming majority of climate scientists accepted

the idea of androgenic global warming. As in the case of evolutionary theory,

political and cultural factors have resulted in large segments of the

population in this country dismissing what is an almost unanimous consensus

among scientists.

• In 1998, cosmologists determined that

the expansion of the universe is accelerating, probably due to dark energy,

something we still don’t understand but which apparently constitutes almost 70%

of the mass-energy of the universe.

These are just a few of the new ideas

that science, by its own rules, has had to accept over the past 50 or 60 years.

I say “had to” because each new idea displaced existing theories that, in many

cases, represented the life’s work of other scientists.

But what, one might reasonably ask, does

all this have to do with writing non-fiction books for children? It’s a

reminder that science is a dynamic, messy affair. It rarely deals in absolutes.

Its crowning achievements often turn out to be incorrect or incomplete. Keeping

this in mind as we write can help us give young readers a more accurate picture

of what science is and how it works.

Published on May 06, 2013 00:00

May 2, 2013

The Road Not Taken

Bergen County Court House, Hackensack, NJ

When I was in high school, I

fully expected to grow up to be a lawyer. It seemed to be an honorable and

exciting way to make a living, at least based on the exploits of the legal shows

I watched on TV. I didn’t actually know any lawyers. My family circle included

loads of CPAs, some doctors, and a bunch of store owners. But that handsome,

young Ben Caldwell on Judd for the Defense sure made the law look interesting.

I’m flashing back to my

childhood plans for a few reasons. First, I’m on jury duty as I write this.

Once every three years, the citizens of my county get themselves to the

courthouse to watch a “You the Jury” film and spend one day in the lottery that

plucks jurors from the general population. This time, the film struck a chord

because it was introduced by Stuart Rabner, Chief Justice of the New Jersey

Supreme Court. Back in the early 1970s, when both of us were teenagers, our

dads were undergoing medical procedures at the same time. I remember the future

Chief Justice from the hospital waiting room.

Today there were four

possible trials needing jurors, three civil and one criminal. I got called for

the criminal pool, but was excused after I informed the judge about my

approaching book deadline. (Fortunately, I didn’t even have to make a lame joke

about how my editor might turn up on his docket for murdering me if I was too

late with the manuscript.) It was a gun possession case with two defendants and

three lawyers. From my vast experience watching The Good Wife and the various incarnations of Law and Order, I know that the more lawyers you have, the longer

the trial will be.

That’s not the only reason

lawyers are on my mind. I also recently attended an alumni conference at my

college alma mater, where about 80 percent of those present seemed to be

lawyers. Some were corporate attorneys, to be sure, but the vast majority were

involved with social justice issues like marriage equality and sexual abuse in

the military. I admit I was envious at their abilities to not just talk (or

write) about change, but to do the nitty-gritty work of making it happen. While I don’t regret my ultimate career path, I kind of respect my younger self

for my good intentions.

So what happened to my

aspirations to the law? I took a constitutional law course sophomore year in

college and realized that legal reasoning didn’t seem to have much in common

with actual logic. I just couldn’t wrap my head around the extent to which

semantics dictated the outcome of a case. The “letter of the law” seemed to

depend so much on the actual wording of a statue that common sense was lost in

the process. I preferred to use words to inform, rather than to debate. So I

switched my major from Politics to History and never looked back.

Published on May 02, 2013 21:30

Paperback Writer? -- Guest Post from Karen Blumenthal

In the world of nonfiction for

young people, California librarian Jonathan Hunt is one of my gurus. His

reviews and essays are always incredibly insightful, and his latest article in Horn Book is no exception.

His thoughtful look at readers of

children’s and young adult nonfiction comes on the heels of two recent

experiences, the Texas Library Association annual conference and the upcoming paperback

publication of my book Bootleg: Murder,

Moonshine, and the Lawless Years of Prohibition.

I was at TLA because Bootleg is part of the new Spirit of

Texas Middle School program, which recognizes authors with a Texas connection.

In addition, my book Steve Jobs: The Man

Who Thought Different is on this year’s Lone Star list for

middle-schoolers, and I had a chance to visit with some of the amazing

librarians who devote their precious spare time to reading and picking books

for these lists.

One of them surprised me with her description of her

readers. Her middle school students are “insulted” by heavily illustrated

nonfiction and almost shun them, she told me. Instead, they gravitate to smaller

books like Steve Jobs because it’s

neither too thick nor too thin, and it is sparingly illustrated.

Hunt said almost the same thing in

his essay, noting that “too many photographs can rob author and reader alike of

the opportunity to exercise their imagination.”

As an avid nonfiction reader who

As an avid nonfiction reader who

would appreciate more photos and relevant images in adult books, I always assumed

illustrations brought a greater depth and visual dimension to a true story. But

they have another side effect: To properly display images, nonfiction children’s

books are somewhat larger than fiction books, which gives them the appearance

of either picture books (babyish!) or coffee table books (and who wants to

actually read those?)

In fact, Hunt makes the case for

smaller “novelistic” book sizes for factual stories, saying that they circulate

easily in his library, without any special selling from him.

That’s encouraging news for Bootleg, which is the first of my four

books for young people to go from hardcover to trade paperback. (Steve

Jobs was published simultaneously in hardcover and paperback.)

Lauren Burniac, who oversees the

paperback imprint Square Fish, says the Bootleg

paperback, which will be out in late July, will be smaller in size than the

original, which itself had a smaller trim size than many contemporary

nonfiction books.

Paperback edition

While many young adult and

children’s novels are published in paperback about a year after their hardcover

publication, few nonfiction books make the leap. But with Common Core Standards

calling for more students to read nonfiction and with school and library budgets

tight, Burniac says that roughly a quarter of her paperback list is now

nonfiction, up from just two or three titles before.

“We’re making a real effort to

bring nonfiction into paperback,” she says, with the hope that a lower price

will bring the books not just into libraries, but also into classrooms. (And, I hope, maybe on to home bookshelves!)

Will a paperback nonfiction book in a smaller size attract

more buyers and more readers?

Or does that old publishing saw

hold, that people choose fiction for the authors and

nonfiction for the subject?

What do you think?

young people, California librarian Jonathan Hunt is one of my gurus. His

reviews and essays are always incredibly insightful, and his latest article in Horn Book is no exception.

His thoughtful look at readers of

children’s and young adult nonfiction comes on the heels of two recent

experiences, the Texas Library Association annual conference and the upcoming paperback

publication of my book Bootleg: Murder,

Moonshine, and the Lawless Years of Prohibition.

I was at TLA because Bootleg is part of the new Spirit of

Texas Middle School program, which recognizes authors with a Texas connection.

In addition, my book Steve Jobs: The Man

Who Thought Different is on this year’s Lone Star list for

middle-schoolers, and I had a chance to visit with some of the amazing

librarians who devote their precious spare time to reading and picking books

for these lists.

One of them surprised me with her description of her

readers. Her middle school students are “insulted” by heavily illustrated

nonfiction and almost shun them, she told me. Instead, they gravitate to smaller

books like Steve Jobs because it’s

neither too thick nor too thin, and it is sparingly illustrated.

Hunt said almost the same thing in

his essay, noting that “too many photographs can rob author and reader alike of

the opportunity to exercise their imagination.”

As an avid nonfiction reader who

As an avid nonfiction reader whowould appreciate more photos and relevant images in adult books, I always assumed

illustrations brought a greater depth and visual dimension to a true story. But

they have another side effect: To properly display images, nonfiction children’s

books are somewhat larger than fiction books, which gives them the appearance

of either picture books (babyish!) or coffee table books (and who wants to

actually read those?)

In fact, Hunt makes the case for

smaller “novelistic” book sizes for factual stories, saying that they circulate

easily in his library, without any special selling from him.

That’s encouraging news for Bootleg, which is the first of my four

books for young people to go from hardcover to trade paperback. (Steve

Jobs was published simultaneously in hardcover and paperback.)

Lauren Burniac, who oversees the

paperback imprint Square Fish, says the Bootleg

paperback, which will be out in late July, will be smaller in size than the

original, which itself had a smaller trim size than many contemporary

nonfiction books.

Paperback edition

While many young adult and

children’s novels are published in paperback about a year after their hardcover

publication, few nonfiction books make the leap. But with Common Core Standards

calling for more students to read nonfiction and with school and library budgets

tight, Burniac says that roughly a quarter of her paperback list is now

nonfiction, up from just two or three titles before.

“We’re making a real effort to

bring nonfiction into paperback,” she says, with the hope that a lower price

will bring the books not just into libraries, but also into classrooms. (And, I hope, maybe on to home bookshelves!)

Will a paperback nonfiction book in a smaller size attract

more buyers and more readers?

Or does that old publishing saw

hold, that people choose fiction for the authors and

nonfiction for the subject?

What do you think?

Published on May 02, 2013 01:00

April 30, 2013

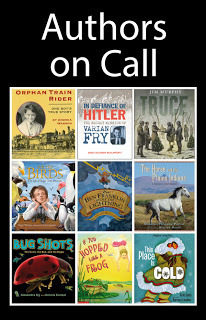

Authors on Call

iNK Think Tank has

been pioneering a new kind of interaction with schools through Authors on Call,

a group of nine nonfiction authors who are equipped to do interactive

videoconferencing. (Many authors now

Skype but there are other ivc technologies that some schools prefer.) We call our programs Class ACTS where “ACTS”

is an acronym for Authors Collaborating with Teachers and Students. They are not exactly school visits nor are

they professional development for teachers but a hybrid that takes the books

and expertise of an author and “bakes” it into the classroom experience with

the “buy in” of the teachers and the students. Andrea Warren wrote up her Class

ACTS experience and posted it on this blog here. Let me give you some other examples.

I have been working with, Sarah Svarda, a media specialist

from Discovery School in Murfreesboro, TN.

She is using me as a mentor to help her 120 4th, 5th,

and 6th grade library students learn how to do research. She teaches these students once or twice a

week and since she has so many students and interactive videoconferencing is more

effective with groups of 40 or less (so that kids can ask questions) we decided

that I would meet the students in smaller groups over the period of time that

they were doing their research. Sarah would then model the lesson to the other

students who didn’t interact with me. So

I met with the 4th grade just when they were starting the program,

then with the 5th grade as they were several weeks into their research

to help direct it more specifically, and then with the 6th grade as

they were starting to write. I have one

more session to go, which will be some kind of wrap-up.

The students’ original idea of “research” is

to look something up in an encyclopedia (or Wikipedia) and write up what they find,

which often includes verbatim material, and turn it in the next day as homework. So, in effect, I was teaching them what I do

when I start a project—a long term process that changes over time. As it happens, I’m just beginning a new book

on hurricanes, so I do what all nonfiction authors do. I went to the library and took out every book

on hurricanes I could lay my hands on. I

showed the kids my pile of 25+ books and told them that I start by reading a

lot of sources. This was a real

eye-opener for them. I told them that I don’t read every book but that I look

at all the books and read the ones that grab me first. This was another eye-opener—comparing sources

and expressing preferences for different writers. In addition to the 4 videoconferences, Sarah

and I also chronicle what we do on a wiki—a communal document. You can see the wiki for our work, as can parents and other people in the public, but only Sarah and I can write on

it. Read it from the bottom up to get

the chronology of our progress.

We are also working with a group of teachers in PA. Sue Sheffer is a retired educator working

with the York School District on a Library of Congress grant to help teachers

use primary source material. The group

is scheduling sessions with our history authors: Roz Schanzer, Carla McClafferty, Jim Murphy, Andrea

Warren plus Myra

Zarnowski, our children’s lit consultant,who wrote a terrific book for

teachers: Making Sense of History . The

raves for each author have been off the charts.

Alexandra Siy is working with teachers from Lewis and Clark

Elementary in Missoula, MT. They are

using her book Cars on Mars as a

mentor text for their own research. Here

is the link to their wiki. Again, the enthusiasm for the program is

unequivocally positive.

Here’s what our Class ACTS programs offer that is different

from a school visit or professional development for teachers:

Author school visits are considered

“enrichment.” Class ACTS are programs

that are aligned with the curriculum and the classroom work of the students. They

take place over a period of time from two weeks to several months. They bring the excitement of a school visit to daily work, although the author isn't present on a daily basis. Since a Class ACTS program is no ephemeral one-shot, it can be transformative for students.

An author visit is about the author and the

author’s book. Class ACTS is about students and their work. The shift is to the “demand” side of the

school money—it’s where the rubber meets the road in terms of results, so here

authors can make a profound difference. Students are discovering that doing

work in depth produces a more thoughtful learning experience than simply “covering”

material. And content is now starting to matter again.

All educators know that the key to learning is

motivation. When students are motivated

they will do the hard work of learning.

Having an author involved in the process provides motivation. Studies have shown that another character

trait exhibited by successful people is grit.

I maintain that none of us nonfiction authors would be here without

it. We also exemplify the skills

mandated by the Common Core Standards.

Scheduling is much more flexible than a school

visit because it’s just a short time during the day and you don’t need travel

time, etc. So the videoconferences are

booked with a short lead time and are given at the optimum time for the

students.

Teachers find that all day professional

development sessions are not nearly as

useful as having a personal learning network—a place to go to ask a quick

question on an as needed basis. Through

Class ACTS, an author becomes a part of the teachers’ pln with very positive

outcomes.

Last year, Authors on Call piloted a program with many

authors and one school. This year we have

sold a variety of programs and we’re

learning all the time. Here’s some of

what we’re discovering:

The teachers we’re working with this year are

PHENOMENAL. Make no mistake, there is a

lot of extra work figuring out how to use us and our books and our skills so

that students benefit. The teachers we’re

currently working with are early adopters who see something for themselves in

taking a risk and doing something different.

As a result, they are, perhaps, a self-selected group totally committed

to their students and are doing the lion's share of the work. We authors are

learning from them in this truly collaborative effort. I have no doubt that our

incredibly successful outcomes are due to the quality of the teachers we’re

working with.

Last year, in our pilot program, the best

teachers were the ones that signed on first.

They created a bandwagon effect with other teachers joining in because

they didn't want to be left out. But the

teachers who joined later were not as effective

A successful program depends on planning, collaboration

and commitment. But the rewards are beyond anything anyone imagined in terms of

student output. It is humbling to see

how much talent children have when you give them the opportunity to strive, think,

create and shine.

It takes patience for a new idea to take

hold. The success of Authors on Call

depends on schools that have the videoconferencing technology to understand the

value of books and authors and for schools that appreciate books and authors getting

the technology. We’re moving forward,

however, and Authors on Call is leading the way.

For more information on Class ACTS programs, you can

download a pdf of our brochure here.

Published on April 30, 2013 21:30