Danny Dorling's Blog, page 21

March 3, 2019

Brexit – the Ides of March

The ides of March, March the 15th, is the date on which Romans traditionally settled debts. It was the date Julius Caesar was murdered. The phrase is associated with turning points in history.

Why, exactly two months before this date, did the UK prime minister fail to secure a deal acceptable to all but a small minority of MPs on the 15th of January 2019? Only 196 Conservative MPs voted to support her that day, the day when the first ‘meaningful vote’ was held. Only another half a dozen other members of parliament rallied to her cause, notably not including her supposed allies in the DUP. Some 432 MPs opposed the deal she presented. It was the worst defeat that any British government has ever suffered. January 15th 2019 dwarfed the terrible defeats of 1920s governments and was almost three times larger than the worse defeat any government suffered in the 1970s – the last two most contentious electoral decades, and the last two decades which were turning points in British economic and political history.

Why did the Prime Minster present a ‘deal’ that was so awful that even her own MPs, in such huge numbers, rejected it? One answer was that no better deal could be negotiated. The bargaining position of the UK, in its attempts to leave the EU, is so awful that Mrs May and all her hundreds of officials and all the many resigning and rebounding Brexit and Exit ministers were simply unable to come back with anything better. This was even after many protracted months of negotiations, begging and pleading, with the well-meaning negotiators of the rest of the EU 27. The 588 pages was it. The best that could be arranged if the UK really wanted to leave. That, at the end of the day, was all that could reasonably be put on the table. It happened like this because the vast majority of EU countries, especially the larger and more powerful countries, have so little to lose from the UK leaving in comparison to what the UK has to lose.

This you need to know if you are working in public service. If you are the head teacher of a school where you lose sleep because the school meals you provide are the most important thing for many of the children in your school, and they grow thinner during the ‘holidays’, then you are obviously worried about the cost of food rising. You will be worrying about your school catering staff who are EU but not UK citizens. This situation is particularly acute in poorer parts of London. But similar reasonable fears can be found everywhere. If you are running a hospital in the Midlands, you will be greatly concerned about how you can continue to supply the same number of routine operations after March 29th without all the staff you need. Furthermore, you will have been talking to the hospital pharmacist about medical supplies, you too are become increasingly understandably frightened. I have talked to so many public sector professionals who are scared in recent months that I have lost count of the examples of what may be about to go so badly wrong.

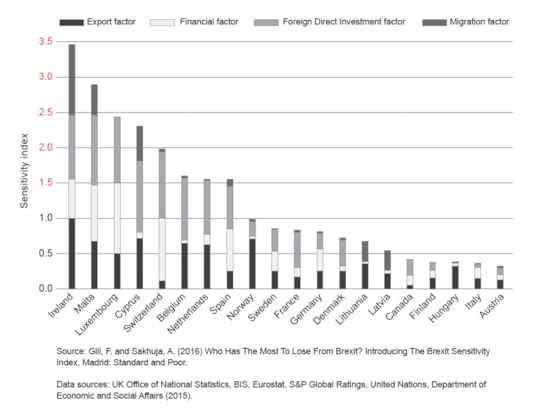

We desperately need to know why we are where we are. A few weeks before the Referendum was held in June 2016 a finance firm, Standard and Poor, produced a graph that still helps today to explain the situation (see Figure 1 below). That graph is reproduced below and shows their estimates of which other countries in Europe would be most adversely affected by the UK leaving the EU.

Figure 1: European countries most effected by Brexit other than the UK, estimates made in spring 2016:

European countries predicted to be most effected by Brexit other than the UK in spring 2016

From the Book by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson: Rule Britannia, Brexit and the end of Empire, London: Biteback

Figure 1 shows that the one non-UK European country most effected by a hard exit would be Ireland. However, Ireland is also benefitting from being an obvious destination of choice for companies that wish to relocate from the UK to an EU member state where the common everyday language is English. Dublin is currently experiencing an economic renaissance. The second most effected country is Malta, which is very small. The third most effected country is Luxembourg, which is very small. The fourth most effected country is Cyprus, which is very small. The fifth most effected country is Switzerland, which is not a member of the EU and which is not involved in the negotiations. None of these most effected countries are especially greatly affected economically. Furthermore, there is (and can be) no border on the Ireland of Ireland. English politicians have been very slow to understand that. Although not also understanding who economically unimportant the UK has become, in terms of what it can supply to the rest of the EU that is vital, could be seen as similarly stupid.

The UK is utterly divided on Brexit. By a narrow majority the bulk of the votes to Leave were supplied by people who live in the South of England. At general elections most of those who voted to Leave normally voted Conservative or UKIP. Most Conservative voters voted Leave. Most Leave voters were (and still are) social class A, B or C1. You need to understand all this when you are trying to figure out why British politicians, and especially Conservative MPs, are acting in such perverse ways. In many ways they are simply reflecting the wishes of a very vocal group of their supporters; and so very rich Brexit funders.

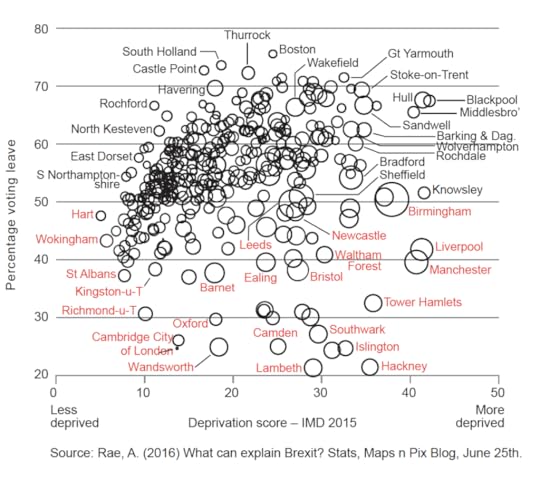

Figure 2 (below) shows the geographical correlation of the Leave vote verses deprivation. The correlation was 0.03. In other words, there was no correlation with deprivation at all. Within some of the local authority areas shown in Figure 2, people in the poorer parts of the district will have been more likely to vote Leave. This is especially the case in London, Oxford and Cambridge. However, in just as many cases it will have been better-off people who more often voted Leave within at least as many other local authority districts. The Leave voters there were disproportionately older people who owned their homes outright. This was especially the case where the bulk of Leave voters were to be found, in the leafier parts of southern countries.

Figure 2: The proportion of those who voted voting leave verses the deprivation score of each area in England:

The proportion of those who voted voting leave verses the deprivation score of each area in England

From the Book by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson: Rule Britannia, Brexit and the end of Empire, London: Biteback

Brexit reflected the rise of the far-right in the south of the UK over many decades. Towards the end of that process the southern concentrated Conservative party formally broke away from the mainstream Europeans Conservatives in 2009 and completed their exit from the European mainstream in 2014. In that year the speculation was that they would merge within the European Parliament with the ‘Belgian right-wing liberal Lijst Dedeker, the Danish People’s Party, Italian Lega Nord MEPs and a number of Latvian and Lithuanian MEPs currently part of the Union for a Europe of the Nations group.’ In the event they also initially ganged up with the neo-Nazi ‘Alternative for Germany’ party, until that group switched its European parliamentary allegiance to the UKIP grouping in 2016. The majority of British MEPs belong to European party groups that are to the right of mainstream European Conservatives. UK Conservative and UKIP MEPs are by far the largest group of far-right MEPS in Europe. You have to know this if you want to know how the UK is viewed from the mainland, and why all this is happening. In 2014 a majority (52%) of British people who voted in the European elections voted right-rate by European standards.

To be clear: UK Conservatives are the largest contributors of MEPs within the far-right ‘European Conservatives and Reformists’ group in the European parliament. UKIP are the now largest group within the “Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy” extreme-right grouping in the European parliament. Here far-right means to the right of mainstream European Conservatives. Extreme right means to the right of the far-right. Europe’s far- and extreme-right will be in trouble without all these UK MEPs in the near future. That is not a concern for the EU negotiators.

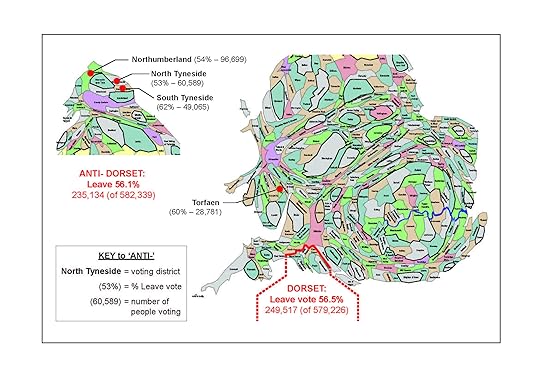

Finally, when you are wondering what is happening over the course of the next few weeks and who brought this all about, consider the map shown in Figure 3. I have produced 28 such maps, one for every county in all of the South of England. In each and every case the electorate of the county in the South is lower than the electorate of a set of comparator areas (in this case the comparator is labelled ‘Anti-Dorset’). In each and every single case the Southern English county provided more Leave voters. In no case have I had to use the same area twice, and I have included every single area that voted in all of the UK in constructing these 28 comparisons. Figure 3 shows just one of the 28 maps. It shows that Dorset was more important than impoverished Torfaen in Wales, North and South Tyneside and the whole of Northumberland in getting the UK into the situation it finds itself today. If we don’t even understand this, we are going to find so much of what will happen next impossible to understand.

Figure 3: A comparison of voting in the referendum in Dorset as compared to areas outside of the south of England

A comparison of voting in the referendum in Dorset as compared to areas outside of the south of England

Part of a series of figures for each county of the South of England, in preparation, to appear here.

There are reasons behind the reason behind the reasons. On the day of the first meaningful vote, January 15th 2019, Sally Tomlinson and I published a book “Rule Britannia: from Brexit to the end of Empire” in which Figures 1 and 2 in this article were first presented and in which we trace the reasons back and back to eventually get to the legacy of the British Empire. You may well not agree with much of what we have written. A summary is here: http://www.dannydorling.org/books/rul...

But whatever your view is, you have no excuse not to know the basic facts about how weak the bargaining position of the UK was, who most voted out, and where most of them lived. No one who is numerate should blame the north, or the poor, or the working class for what is about to become us. On valentine’s day, February 14th 2019, Mrs May suffered yet another humiliating House of Commons defeat a by 303 to 258 votes. A fifth of her party did not support her, six Conservatives voted with Labour. Beware the Ides of March.

For a pdf of this article and the on-line version in Public Sector Focus click here.

February 27, 2019

Is the Human Species Slowing Down?

In the ‘Origin of Species’, Charles Darwin described how a population explosion occurs. He called the events required – ‘favourable seasons’. Charles was not to know it, but such circumstances arose for his own species at around the time of his own birth. However, the favourable seasons for human population growth were not experienced favourably, with times of great social dislocation – ranging from small scale enclosure, right through to global colonisation.

Now those seasons are over we have experienced the first ever sustained slowdown in the rate of global human population growth for at least one generation. However, we are not just slowing down in terms of how many children we have, but in almost everything else we do (other than the rise in global temperatures we live with). Even the size of the rise in global student debt may now be slowing. If this is true – what does it mean? And what measurements suggest it is true?

in January 2019, the press reported that: “Jørgen Randers, a Norwegian academic who decades ago warned of a potential global catastrophe caused by overpopulation, has changed his mind. “The world population will never reach nine billion people,” he now believes. “It will peak at 8 billion in 2040, and then decline.”

Similarly, Prof Wolfgang Lutz and his fellow demographers at Vienna’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis now predict the human population of the planet will stabilise by mid-century and then start to go down.

And a recent Deutsche Bank report now suggests that the planetary population will be peaking at 8.7 billion in 2055 and then declining to 8 billion by century’s end.

In February a reviewer in the Times newspaper wrote that: “The world’s population may be about to contract” and questioned whether this might be good news, or not. So there is much to debate:

In this audio recording of a talk, Danny Dorling is speaking at the Cambridge University Scientific Society, on February 26th 2019, in the Pfizer Lecture Theatre of the Chemistry Department:

February 25, 2019

The Key to the Brexit Backstory

How did Britain’s wealthy take the end of the British empire? Not well — and the rest of us are still paying the price.

The British empire may strike many of us as distant history that has no more than a marginal impact on our 21st-century lives. But we can’t really understand Brexit — the British move to exit the European Union — without understanding how that empire ended and, more pointedly, how Britain’s rich reacted to that demise. Two scholars at the University of Oxford, Sally Tomlinson and Danny Dorling, have an incisive new book out that explores the chain of events that have brought us to Brexit. This excerpt from that book, Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire (Biteback, 2019), offers a historical perspective that seldom informs our daily news doses on the latest in Brexit manoeuvring.

Partly, if not largely, because of failing to come to terms with its loss of a huge empire, the UK had been ramping up economic inequality since the late 1970s, reaching a point where the gap between rich and poor in Britain was wider than in any other European country. When India, and then most colonies in Africa, won their freedom, the British rich found themselves suddenly becoming much poorer. They blamed the trade unions and socialists in the 1970s. To try to maintain their position, from 1979 onwards they cut the pay of the poorest in a myriad of ways and vilified immigrants in the newspapers they owned or influenced, while managing to hold on to some of the pomp and ceremony that their imperial grandparents had enjoyed.

Something had to break, and, in the end, it was a break with the EU – it was Brexit. It is true that Brexit was partly the language of the unheard – the masses cocking a snook at the demands of their over¬lords – and there were some who actually believed the propaganda that problems in health, housing and education were due to immi¬grants, and some who really thought ‘their’ country was being taken over by colonial and EU immigrants, by refugees from anywhere, or even by Islam. But there were many others who voted Leave out of hope. They just hoped for something better than what they had.

The British had been distracted from the rise in inequality and the consequent poverty that grew with it by decades of innuendo and then outright propaganda suggesting that immigration was the main source of most of their woes. Without immigrants, they were told, there would be good jobs for all. Then they were told, at first in whispers, and later through tabloid headlines, that without immigrants their children could get into that good school, or the school they currently go to would not be so bad. Without immigrants, they could live in the house of their dreams, a home currently occupied by immigrants who have jumped the queue and taken their birthright. ‘We’ (always ‘we’, always ‘us’) need to cap net immigration to the ‘tens of thousands’ and then all will be so much better. All this was said to distract people from looking at who was actually becoming much wealthier and who was funding a political party to ensure that the already wealthy could hoard even more in future. Or, as Alex Massie of The Spectator wrote in 2016:

“If you spend days, weeks, months, years, telling people they are under threat, that their country has been stolen from them, that they have been betrayed and sold down the river, that their birthright has been pilfered, that their problem is they’re too slow to realise any of this is happening … at some point some¬thing or someone is going to snap.”

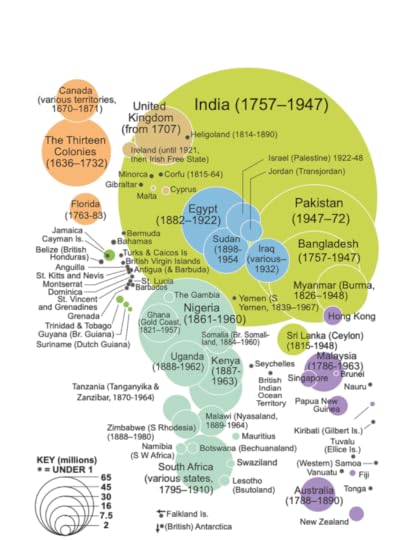

The British Empire – by population today

Sally Tomlinson is emeritus professor at Goldsmiths University and honorary fellow of the education department at Oxford. A selection of her work appears in The Politics of Race, Class and Special Education (2014) in the Routledge World Education series. Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor in geography at the University of Oxford. His work focuses on housing, health, employment, education, wealth, and poverty, and his books include The Real World Atlas (Thames and Hudson), Inequality and the 1% (Verso), Population 10 Billion (Constable) and All That Is Solid (Allen Lane).

Click here for PDF and published version of this blog.

February 20, 2019

(Mis)Rule Britannia: Brexit is the last gasp of empire

Brexit represents the last gasp of the British empire, argue Sally Tomlinson (Goldsmiths, University of London) and Danny Dorling (University of Oxford) in a blog for the LSE published on February 20th 2019. The men who have led it cannot accept that the colonial era, and the exploited wealth that came with it, is over.

The article is below. A talk trying to explain the sorry mess Britain finds itself in, given on the day this blog was published, can be listened to by clicking the play button here:

Public Lecture by Danny Dorling about the book “Rule Britannia”, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, February 20th 2019.

All imperial countries and their leaders have problems when their empires disappear, and they no longer have the forced tribute or inequitable trade deals they have depended on. Even when previously colonised people come to work for their former masters and build up the ‘mother country’, they may find a distinct lack of hospitality and even face deportation in their old age. So, as the sad tragedy known as Brexit moves into its assumed final stages, it is time to revisit the British Empire and its ending – Brexit being perhaps the last gasp of this empire.

Picture: Cover of a Seamen’s Hospital booklet via Europeana and the Wellcome Collection and a CC BY 4.0 licence

Brexit is a gasp of rancour which seems to have brought to the surface much resentment, hatred, and ill-informed debate. Even Theresa May could not possibly have envisaged a situation where, faced with headlines such as “Officials warn of putrefying piles of waste after no-deal Brexit”, and the current UKIP leader writing to the Queen telling her she had committed treason by signing the Maastricht Treaty, she (May, not yet the Queen) is forced to return to the EU in late February, to try to renegotiate that infamous withdrawal treaty that in January Parliament had rejected and the EU had said it would not renegotiate.

May will not be helped by her international trade secretary announcing (to a Conservative think-tank) that EU countries would now be keen to negotiate due to weaknesses in their economies. Nor will she be helped by what was quickly labelled as the ‘Malthouse compromise’ on the backstop, after a junior minister (Kit) who claims (in Who’s Who) that his hobbies are baking bread and watching others dance and play.

Only a couple of generations or so ago, Britain was in control. It was in control of more people in an empire larger than any other there had ever been in the history of the world. The disappearance of this empire led inexorably to a loss of control of land, labour, wealth and also to what sustained an imperial identity. Clinging to fantasies of empire, a group of people – led by those mainly educated in schools designed to produce the rulers of empire – are today in the process of creating an era of misrule and mistakes that will have serious consequences for all the people of the four nations that currently make up Britain, those in many connected European countries, and well beyond.

A major consequence of the misrule of Britannia is possibly the further dissolution of the UK (most of Ireland having left the Kingdom a century ago). Polly Toynbee rightly pointed out in 2017 that the Irish border was ‘a road block to the fantasies of Brexiteers, reviving deep-dyed contempt for the Irish’ who at that time were dismissing it ‘with an imperial fly-whisk’. Ireland, the first country to be colonised by the English in 1169, was divided in 1922 by a hated border. During the 30-year long Troubles from 1969 to 1999, the British army blockaded country lanes, and the Provisional IRA booby-trapped roads. Could no-deal lead it again into violence, or even into a vote for a United Ireland?

The misplaced nostalgia for a British empire – a time when by force and violence Britain did indeed ‘rule the waves’ for a long period – has been used by the small number of influential people we have documented in our book, Rule Britannia: Brexit and the end of empire, who have a dangerously imperialist misconception of the country’s place in the world. These misconceptions often began in childhood. Where else do the ideas of taking back control of a mythical country come from? Once upon a time the ‘Romance of Empire’ book series told children that “England was a gallant little nation whose power and conquests are obviously the rewards of merit since all her opponents are bigger and uglier than she is”(cited in JS Bratton), and the world map had large pink bits which we were told ‘belonged to us’. The Brexiteer master manipulators used such memories to take control of the opinions of some voters through a campaign notable for lies and misinformation.

Misrule by misinformation was, and is, also notable for fantasies about free trade – either with a Commonwealth (of 53 countries, 31 with fewer than three million people) who have not so far been too enthusiastic about trading with a country which once took their land and labour and protected its own trading position – or with the world’s largest economies, who are embroiled in their own trade disagreements. The imperial days when raw materials and slave or indentured labour overseas created an industrial revolution have long gone, and manufacturing has shrunk to 10% of the UK economy. The British state may be good at making and selling arms, perhaps unusually good at spying and tourism too, but even selling good higher education may be impeded by mean-spirited immigration rules and high fees creating Giffen goods.

Across Britain, for over a hundred years, misrule by disinformation has created in many people a particular dislike of almost all foreigners, immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Those who voted to take back control of immigration were unlikely to have known about legislation such as the 1905 Aliens Act – designed to keep out East European and Jewish migrants – or the 16 immigration control acts passed since the invited arrival of post–war migrants from former colonies. There has been minimal information about the current immigration bill before Parliament, which aims to control migration by cash. Those earning less than £30,000 are apparently too poor or low-skilled to deserve entry into the country.

Lies and misinformation about immigrants, especially those who arrived after the end of the second world war, reached fever pitch during the referendum campaign. And those lies have recently become shriller and nastier. From the 1960s onwards, people were told that without immigrants there would be more employment for ‘British workers’: more housing, good schools and welfare benefits for the deserving. The truths were seldom reported: poorer immigrants from former colonies took jobs the ‘native’ Britons did not want, they lived mainly in private not public housing in city areas where their labour was needed, and mostly attended schools for the working classes which had never been that good. In fact it was their arrival that made the schools better, especially in London.

Grotesque inequalities in a supposedly rich country have been blamed on anyone or anything other than the inability of the British rich to share a smaller domestic pie, once the last of the colonies was gone.

The 1930s – when the empire was still more or less intact – saw similar inequalities between rich and poor that we see now. It was the disappearance of the empire after the war, when the looting of land and labour diminished, that led to the rich becoming poorer. This was blamed on immigrants, despite their labour and taxes contributing to the country’s wealth – and on socialists and trade unions. There was barely a mention of friends in Saudi Arabia and other oil countries raising oil prices, or of how other European countries managed to avoid the growth in inequality that the UK has experienced since 1978.

Peak Inequality, as Danny Dorling’s book describes it, may now have been reached. The richest of all work so very hard to avoid paying taxes by sending money to the 14 overseas tax havens that are still British protectorates. A few are even paying for Ubercopters to pick up tired skiers and return them to their fondue and wine. The consequences of no longer ruling the lands, the waves or the skies of imperial times will have consequences that are now only slowly becoming apparent. Empires only finally end when the elite children – those that were related to the last emperors, viceroys and colonial governors – are no longer running the shell that remains.

Reference

Bratton, J. S. (1986) “”Of England, home and duty: Images of England in Victorian and Edwardian literature” in (ed) JM MacKenzie: Imperialism and Popular Culture. Manchester. Manchester University Press.

Sally Tomlinson and Danny Dorling will discuss Inequality, Brexit and the End of Empire at an event at the LSE on Friday 29 March 2019. Find out more here.

Sally Tomlinson is an Emeritus Professor at Goldsmiths, an Honorary Fellow in the Department of Education, University of Oxford, and an Associate in the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick.

Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford and the author of numerous books on issues related to social inequalities in Britain, including Peak Inequality: Britain’s ticking time bomb (2019), Policy Press.

They are the joint authors of Rule Britannia: Brexit and the end of Empire (2019), Biteback.

Click here to read more of this post as a PDF file or on-line.

February 18, 2019

How Inequality and Austerity have Divided Britain,

What does Brexit tell us about ourselves – and what will happen now?

An audio recording of an open public meeting organised by Cheltenham Labour Party and held in Cheltenham on Friday 15th February 2019:

Flyer advertising :How Inequality and Austerity have Divided Britain, what does Brexit tell us about ourselves – and what will happen now

February 13, 2019

Connections: Global Inequality, the British Empire and Brexit

Danny Dorling speaking at the monthly meeting of “Global Justice Now”, Oxford Town Hall, February 12th 2019.

Global Justice Now campaigns on all aspects of social and economic justice, with a particular (but not exclusive) focus on people in the Global South. Our main campaigns at the moment are focusing on:

• Trade Deals, in particular putting democratic decision-making at the heart of trade policy.

• Migration, focusing both on harmful government policies and negative media coverage.

• Pharmaceuticals, challenging the corporate control of medicines. This is an interesting campaign area because whilst our focus is on the Global South, the UK NHS is challenged by the same issue.

• Food, championing small-scale food producers who are under threat by the increasingly dominant role of very large corporations.

The talk is based on the book “Rule Britannia“. And was given as Theresa May was supposed to be in last minute negotiations with the “EU27”:

A portrait of Theresa May by Erika, February 2019

February 12, 2019

Book launch audio recording: Rule Britannia – from Brexit to the end of Empire

Things fall apart when empires crumble. Rediscovery of past glories is attempted again and again, until eventually those living in what was once the heart of the empire become reconciled with their fate. Many of the British are not yet reconciled. A major cause of Brexit was a stoked-up fear of immigrants, but Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire (Biteback Publishing) argues that at its heart the rhetoric of Brexit was the playing out of older school curricula that had been dominated by empire. Brexit was led by people, almost all men, who mostly had fond memories of something that never was as great as they believed it to be. Co-authors Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson are in conversation. The conversation is chaired by writer and researcher Maya Goodfellow.

Maya Goodfellow, Sally Tomlinson and Danny Dorling, taking about the book “Rule Britannia: from Brexit to the end of Empire“, at the London Review Bookshop, Bloomsbury, London, February 11th 2019

Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the end of Empire – published January 15th 2019

Foreword to: The influence of place, geographical isolation and progression to higher education

Take a minute to think about where current education policy is likely to take us in England, and to some extent in Wales. Scotland and Northern Ireland run things a little differently.

I went to school in England in the years immediately after most state schools had been made comprehensive. In the city in which I grew up, no one really knew whether the old secondary modern (located in the affluent north of the city) was better or worse than what had been the county grammar (located near the manufacturing plants), and most children went to their nearest school.

But when league tables were published in the 1990s, the social divides between local schools began to widen and widen. House prices around good schools soared upwards and those schools were increasingly perceived as ‘better’ and more successful. Upper middle class parents began to calculate whether to avoid the house price hike and instead move their children from schools in weak catchment areas to private schools. Average, but not upper, middle class parents could not afford that option, but they could at least shun the worst areas with greater determination, and so sink and substandard schools became more common. To where will all this logically lead?

Today young people are told to compete ever harder to go to university and to try to go there as quickly as they can, preferably at age eighteen. Since 2012 the cap has been lifted on the number of students any university can take. This shift to competition amongst universities has contributed to devaluing other non-university routes into employment. Muddled attempts to bring back apprenticeships were made, but the educational maintenance allowance was abolished. And then English and Welsh universities began to market themselves everywhere they could with hoardings at bus stations and advertising in social media and even adverts placed on local TV. The message was ‘winners go to university’, especially to universities with the right brand image.

The successful institutions grew and grew. If this continues the city of Durham could soon become seen as solely a university town, the same with Loughborough, and Exeter, and any number of places that stole some advantage in the early rounds of the introduction of ‘the market’. Other institutions will shrink, just as the overall number of eighteen year olds is shrinking. Some smaller universities, particularly those serving peripheral communities, may no longer be financially viable and have to close.

The closure of a university will be disguised as a merger with a neighbouring town’s institution. This withdrawal of provision of higher education from some places will inevitably have a negative impact on the most economically deprived and vulnerable. Coastal towns on England’s North West coast, for example, will become places from which the talented young will flee. We will end up with more and more student ghettos and weaker, diminished communities unless initiatives such as those documented in this report are begun.

British post-war politicians once talked of the brave new world to come in which the old would live in comfortable housing in mixed communities, and through their windows they would watch as ‘parades of perambulators’ passed by, pushed by parents who smiled and waved at both the old and young around them. Some of the children went on to local higher education, others didn’t, but all could be happy and the pay-gap between graduates and non-graduates was soon at its lowest ever. Polytechnics were built for local people, just as universities had been before them. For instance, long before both World Wars, the University of Sheffield was founded with the money raised from thousands of penny subscriptions paid by steelworkers so that their grandchildren would have a university they could attend. The introduction of the market into higher education cruelly stole those dreams and the principle behind that initial investment.

The recommendations in this report will help to initiate the changes required to begin to mitigate some of the worst effects of the opportunity landscape we have created. In a normal small European mainland city there is a normal small European university. It does not boast on its website to be the best (better than all the rest in similar towns). The buildings are often not flashy, but the teaching tends to be excellent, as are the outcomes: a highly skilled multi- lingual, technically able and imaginative workforce.

Opportunities across much of the rest of Europe exist for well funded, good quality further education. That is not the same in Britain where institutions are constantly competing with their neighbours for ‘student FTEs’ and working with the perennial fear of being ‘market failures’. Good education requires some stability. In mainland Europe, the young mostly live with their families, not in student ghettos, or in apartments funded by private finance initiatives with huge returns to recoup. Remote schools and universities are helped out, not penalised.

We have a very long way to go, but with reports such as this we can begin to point the way towards a better destination and a fairer distribution of resources across the higher education sector to support high quality local provision. In Britain, young people from more isolated rural areas and poorer social backgrounds may be particularly vulnerable to losing out in our increasingly market-driven higher education system. Sorting this all out will take time. And will require many small steps.

Foreword to: The influence of place,

geographical isolation and progression to higher education, London: The Bridge Group, February 12th 2019

by Professor Danny Dorling

Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography University of Oxford

read more (full report as a PDF and link to more on-line material).

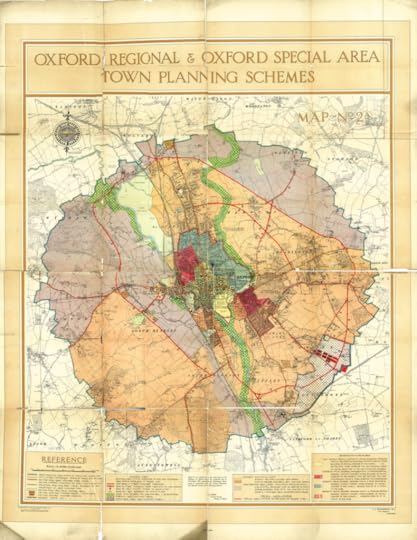

Oxford Regional and Oxford Special Area Town Planing Schemes, 1927

February 7, 2019

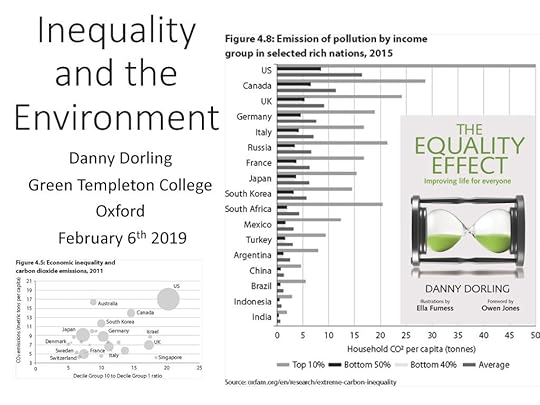

Inequality and the Environment 2019

The first of an interdisciplinary seminar series on the topic of ‘Inequality and the Environment’, organised by Alex Milden.

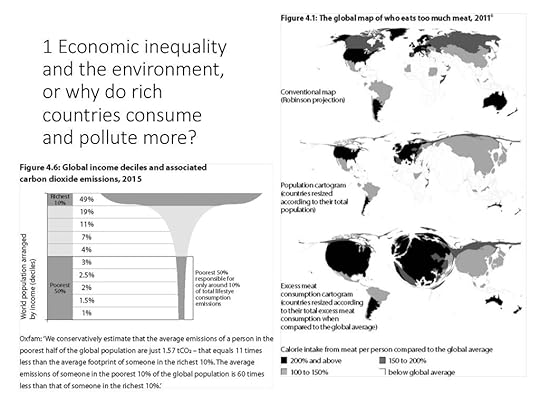

Economic inequality and the environment, or why do rich countries consume and pollute more?

Are there too many people: can the planet cope?

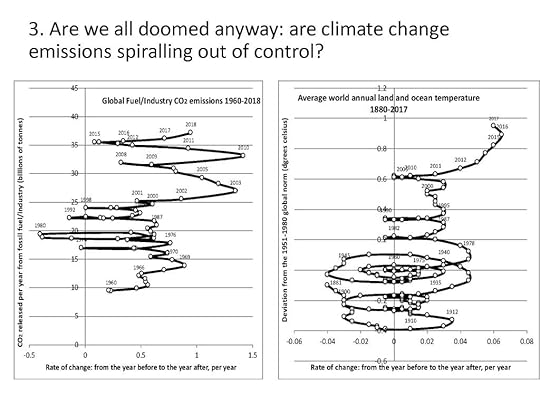

Are we all doomed anyway: are climate change emissions spiralling out of control?

How can social sciences help, or how do we stop the physical sciences stealing our thunder?

Inequality and the Environment introduction

Economic inequality and the environment, or why do rich countries consume and pollute more?

Inequality and the Environment question 1

Are there too many people: can the planet cope?

Inequality and the Environment question 12

Are we all doomed anyway: are climate change emissions spiralling out of control?

Inequality and the Environment question 3

How can social sciences help, or how do we stop the physical sciences stealing our thunder

Inequality and the Environment question 4

February 4, 2019

The spurious link between immigration and increased crime

In the era of Brexit attempts have repeatedly been made to associate recent immigrants with criminality; and despite all evidence to the contrary this slur continues.

Thames Valley – Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC), Anthony Stansfeld

On Saturday 22nd December 2018, three days before Christmas, the Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Berkshire – Thames Valley – Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC), Anthony Stansfeld, was reported to still be standing by his very recent allegation that that ‘foreign nationals’ were one of the reasons for increasing demand being placed upon Oxfordshire’s police officers in recent years . He had been quoted as claiming that “A significant amount of the more serious crime is now being committed by foreign national offenders.” (Photo above: Anthony Stansfeld, Thames valley Police and Crime Commissioner, reproduced with permission of the Oxford Mail).

Local members of parliament reacted angrily. The Oxford West and Abingdon MP explained that “I am concerned that the PCC singling out foreign nationals as the perpetrators reeks of dog whistle politics and risks an increase in hate crimes to people from other nations who’ve made their home in our communities” The Oxford East MP used statistics to explain that the number of people from abroad committing crimes was actually declining, yet still Anthony Stansfeld (pictured above) would accept no criticism, simply claiming that “I tell the truth on these things.”

So where does this particular version of the ‘truth’ come from? And how does it manage to resist so much good sense, statistical evidence, or warnings of the potential consequences of repeating such accusations which are often echoes of a much older prejudice?

Students of criminology could request interviews with the Thames Valley PCC to ask him where his views come from, but he may not know. Few of us make good judges of our own motivations, beliefs, and what lead to our particular prejudices developing in the first place. Fear and mistrust of others is common worldwide, especially of people who are seen as different. However, the reactions of the two members of parliament for the city of Oxford in this case helps to illustrate that there is also now a strong movement to counter such stereotyping, and that fight-back also has a long history.

There is no correlation between immigration rates and crime. Meticulous research recently revealed that Wales has the highest rate of imprisonment of people to be found anywhere in Europe. Wales is hardly a favoured destination for immigrants, unless you count English people moving there in retirement. Wales suffers from one of the lowest immigration rates in all of Europe. In 2014 less than 5% of its population were born abroad (see the map below). This is a rate of in-migration that is amongst the lowest of any country or region in Europe. Outside of London and Northern Ireland the rate of migration from abroad into much of the UK very low. It is a low rate of immigration into a large home born population that is most comparable to that found in many Eastern European countries. Eastern Europe also tends to receive few people born abroad, and is very like the North of England and Wales in that respect. The highest rate of immigration from abroad in Europe is found in Switzerland, a country not known for its high crime rates. Next most attractive is the Mediterranean coast of Spain, where a high proportion of the large number of immigrants were born in Britain (we often call them ‘expats’). After those two areas it is central west London that attracts the most people born elsewhere.

Immigrants: The proportion of people living in each region of Europe born in another country (2014)

Immigrants: The proportion of people living in each region of Europe born in another country (2014)

Key– in the darkest shaded areas over a fifth of people were born abroad, in the lightest areas less than one in twenty was. Areas in the map are drawn in proportion to their total populations. Source, Figure 9.4 of Dorling, D. and Gietel-Basten, S. (2017) Why Demography Matters, Cambridge: Polity (reproduced with the kind permission of Benjamin Hennig)

We have recently written a book in which we try to explain that, people are apt to blame others when the relative position of their place in the world is falling, as it is currently in the Britain. There is a very real sense that things fall apart when empires crumble, and Britain remains, at the heart of what is a still contracting relic of a former world empire. The fear of outsiders in Britain has been stoked up in recent decades by newspapers whose owners want people to blame others, rather than the single political party they almost all support. Above all else they do not want the blame placed on the economic inequality by income that has been allowed to grow to become the worse, to have become the highest, in all of Europe. Some even try to blame immigrants for that inequality too, claiming that their presence lowers wages, as if people choose to be badly paid! But the highest median wages in Europe are found in cities on the mainland with high proportions of immigrants (the dark areas in the map above).

We all too easily fail to see what is happening when the rich take more and more leaving less for the rest, especially for the poorest. We are encouraged to imagine ogres that are not there. These ogres include ever rising numbers of apparently ‘criminal immigrants’, the fictional supposedly quick-breeding migrants who are taking ‘our’ homes, ‘our’ partners’ jobs, and claiming the best places in what should be ‘our’ children’s schools, and at the very same time apparently committing so much crime. However, the most common serious crime in the UK is speeding in a car. It is also by far the most deadly. The vast majority of car drivers who speed are not immigrants, although the Duke of Edinburgh, was recently involved in a collision and then found to be not wearing a seat belt, and he was born abroad. But the reason he choses not to wear a seat belt, or to drive as he does, is unlikely to be related to some early experience he had as a child living in Greece, France and Germany.

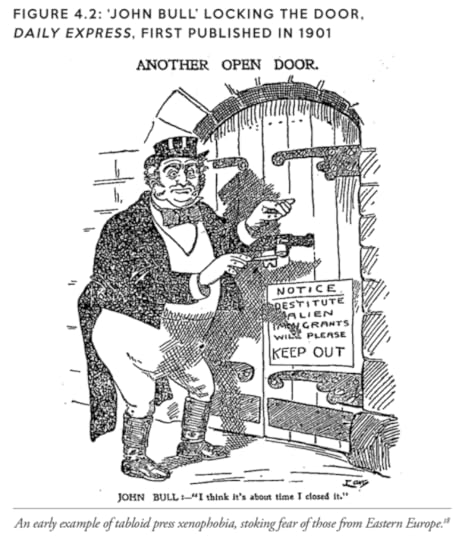

‘John Bull’ Locking the door, Daily Express, first published in 1901

Source, Figure 4.2 of Dorling, D. and Tomlinson, S. (2019) Ruel Britannia: From Brexit to the End of Empire, London: Biteback, Reproduced from the archive of the Daily Express (out of copyright).

Fear of immigrants tends to rise at times when economic fortunes are falling and people are questioning the political strength of their country; scapegoats are searched for. In 1899 the Second Boer war began in South Africa, a war in which the British suffered very bad losses . In 1901 there were racist campaigns against foreign immigrants in the Daily Express. In 1903 George Edalji, a Midlands solicitor with a mixed race background, was found guilty and sentenced to seven years hard labour for crimes he did not commit. His sentence was reduced and he was later found to have not been guilty of the most serious crimes of which he had been accused. However, he was never found completely innocent despite his sister, Maud, campaigning to clear his name for nearly 60 years, right through to her death in 1961. His wrongful conviction did help bring about the establishment of the Court of Criminal Appeal for England and Wales which first sat on May 15th 1908, 111 years ago this year. We can adapt, so when will we learn to stop saying ‘foreign national offenders’?

The crimes people are least likely to be found out for are the common crimes of the rich: driving dangerously, evading taxes, and fraud. The crimes which are most often publicised are the crimes most strongly associated with the poor. Recent immigrants from poor backgrounds are often labelled as racially or ethnically different, living in urban squalor that is apparently of their making (despite the fact that they have only just arrived and have had no time to make it). In contrast, recent immigrants who are wealthy are rarely labelled as living in unusually higher concentrations, but most do. The segregation of the rich away from other people’s neighbourhoods is the most concentrated spatial segregation of all. The rich tend not to mix.

In 2007 it was shown through analysis of the national census that the greatest concentration of overseas born children living in the UK were to be found around affluent Hyde Park in London. They had been born in the USA, their parents most likely worked in finance. In the next year came the great financial crash, for which no banker in the UK was jailed, British, American or of any other nationality.

A century earlier, in 1905, as we recount in our recently book (‘Rule Britannia’) the MP Major Evans-Gordon was instrumental in bringing in the Aliens Act which ‘…gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for immigration and nationality matters. Ostensibly designed to prevent paupers and criminals from entering the country, one of its main objectives was to stop Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe. Campaigning in favour of the law, Evans-Gordon said, ‘Not a day passes but English families are ruthlessly turned out to make room for foreign invaders,’ and ‘The rates are burdened with the education of thousands of foreign children.’ Problems with health, housing and education were all claimed, as now, to be caused by immigration. A little later, the league was absorbed by Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.’ [Note: This quote is an extract from Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the End of Empire, London: Biteback, published January 15th 2019, By Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson; and this article is mainly based on material brought together in that book].

Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the end of Empire – published January 15th 2019

Source, Cover of Dorling, D. and Tomlinson, S. (2019) Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the End of Empire, London: Biteback [an image from the Empire marketing board]

It is good to see MPs today behaving so differently. Less than three years ago one of their number, Jo Cox, was murdered by a man shouting ‘Britain First’ as he killed her, and who gave his name in court on being charged with her murder as ‘Death to traitors. Freedom for Britain’. Since the referendum, racist hate crime has increased by 16 per cent across Britain, and peaked at a 58 per cent rise in the week following the vote.

Hate crime is done to immigrants, not by them. Three weeks after the Referendum a 16 year old Polish girl was found hanged at her school. She had been bullied and told that she ‘did not belong here’. In September 2016 a Polish man was killed in Essex, the Polish Ambassador visiting the scene and expressing shock at the rise of racist and xenophobic behaviour. Long before the Windrush scandal there had been a hostile environment to immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers of all kinds, and a rise of far-right fascist groups in the UK. But many politicians are fighting back against the racism, more than they have ever done so before. Police forces around the country are now better informed and despite cuts, are better equipped to deal with the expectations put upon them. They do not need the spread of untruths by an ignorant Police and Crime Commissioner, or the creation of hostile environments by politicians who appear to harbour a deep dislike of people they see as not like them. It is time we called out the lie of ‘immigrant criminals’ once and for all, for what it is: racism.

Danny Dorling works at the University of Oxford. He was previously a professor at the University of Sheffield, and before then at Leeds. His earlier academic posts were in Newcastle, Bristol, and New Zealand. His most recent book, with Sally Tomlinson, is ‘Rule Britannia: Brexit and the end of Empire’.

Sally Tomlinson was born in Stockport. Her first primary school job was teaching children from the Caribbean and Asian subcontinent in Wolverhampton in the year Enoch Powell was making his anti-immigrant speeches. She has worked in universities in Warwick, Lancaster, Goldsmiths London and Oxford’.

For a link to the full article and a PDF click here.

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers