Danny Dorling's Blog, page 19

May 21, 2019

Brexit and the end of the British Empire, Keele Public Lecture

With gratitude to the man from the Stoke area who asked the first question, after listening to this argument, and said: ‘You put me right’.

Title: Brexit and the End of the British Empire

Abstract: From Brexit the British may learn a great deal about themselves as a result of having voted to ‘Leave’. Not least that Britain, and even Brexit, has its roots in the British Empire. Traditionally British Geography, a subject that was partly born in its current form in Britain due to Empire, has not been very good at explaining what the Empire was and why it mattered so much to Britain. Brexit may well be the point at which the English, in particular, finally learn about the importance of geography. Geography is central to Brexit from the Irish border through to the modern day priorities of India. Living with the highest rate of income inequality in Europe could have been the real problem for the British, not being in the EU. The source of British woes was not immigrants or some perceived lack of sovereignty, but of their own making, and possibly partly an outcome of having so recently been at the heart of the largest empire the world has ever known.

Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the end of Empire

May 6, 2019

Lakin McCarthy Presents Danny Dorling: Rule Britannia

A talk on ‘Rule Britannia, From Brexit to the end of Empire‘ – at Komedia Comedy Club, Brighton, May 5th 2019.

Now is the hour to turn our attention to what really went so very wrong for Britain: accepting gross inequality, not understanding our own history, blaming the north and the working class for what the south and the middle class chose – Brexit. An authoritative, insightful and entertaining look at our controversial past, the anxiety-filled present . . . and the possibility of a fairer future.

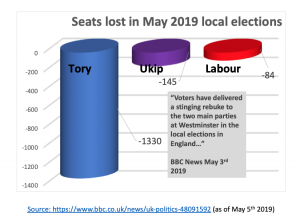

A mock “BBC graphic” of how many seats each losing party lost in the local elections of May 2019

Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the end of Empire

May 2, 2019

Food and Hard Times in Three European Countries

Having enough to eat of a decent quality and quantity has long been a central expectation of what it means to live in a Western country. But today food poverty is a major social and moral concern in Britain and some parts of Europe.

An audio recording of Rebecca O’Connell, Danny Dorling, and Hannah Lambie-Mumford, introduced by Liz Dowler, speaking on Food and Hard Times in Three European Countries, University College London, London, April 30th 2019

Families and Food in Hard Times, is a European Research Council funded study that presents key findings concerning these questions:

• What is the relationship between economic inequality and diet in the UK and other parts of Europe?

• Which types of families are going without enough decent food in different European countries?

• What are the consequences of food poverty for children and families?

• Where do the state and charity figure in addressing food poverty and its causes?

Guest speaker: Professor Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford. ‘Diet, exercise and economic inequality – why is Britain so bad at being European?’

Discussant: Dr Hannah Lambie-Mumford, Research Fellow at Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), University of Sheffield.

Q&A chaired by Professor Elizabeth Dowler, Emeritus Professor of Food and Social Policy, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick.

Danny was talking on “Diet, exercise and economic Inequality – why is Britain so bad at being European?”

The UK is the country of Europe that consistently reports the highest rates of income inequality of any country on the continent. Along with Hungary it reports the worse rates of obesity. Car use, and pollution from cars is excessive, walking and cycling to work is low. As a result, the British get less exercise than most other Europeans. So what is it about Britain that has led to these differences? In the 1970s Britain has the second lowest rate of income inequality of any large country in Europe. Only Sweden was more equal. The population of the UK were generally thin and healthy. Life expectancy was rising rapidly, it has falling recently in the UK. No other country in Europe has falling life expectancy. And car use in the 1970s was low and rates of cycling and walking were high. Not everything was good, but something went very wrong after the 1970s.

‘A picture of Brighton beach in 1976, featured in the Guardian, appeared to show an alien race.’ Photograph: PA.

April 26, 2019

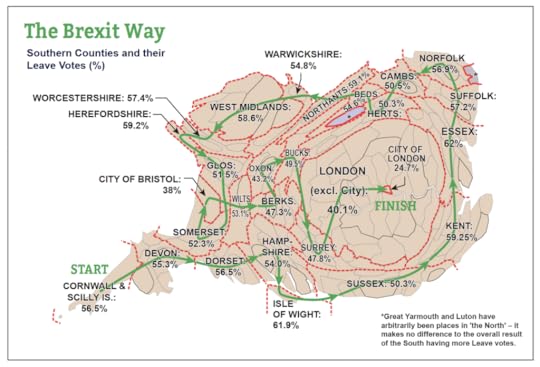

Time for the truth: We ‘left’ the EU because of Hampshire

An illustrated talk by Danny Dorling (on one small part the book Rule Britannia) given at Winchester Skeptics in the Pub on April 25th 2019.

In Hampshire 546,267 people voted to leave the EU in June 2016, some 54.0% of all those who voted in the county. Hampshire was never singled out as a hotbed of leave voters and yet the people of this county, along with just a few of the other English Home Counties, were crucial to securing the referendum result. So why was this not commented upon at the time, or later – and what might it mean for how little we understand ourselves?

We can define a ‘Anti-Hampshire’ which has almost exactly the same electorate as Hampshire but is made of five northern and one Welsh district often labelled as hot-beds of leavers. In Anti-Hampshire only 494,816 voted to leave, 53.7% of all those who voted. Anti-Hampshire consists of Blackpool, Derby, Great Yarmouth, Leeds, Merthyr Tydfil and Sheffield (the fifth largest city in Britain).

It is time for a few home truths about the geography of who we are, how we got here, and where we are most probably going.

The table below is numbers voting leave and the % of all who voted in “Anti-Hampshire”

Blackpool 45,146 (67%)

Derby 69,043 (57%)

Great Yarmouth 35,844 (72%)

Leeds 192,474 (50%)

Merthyr Tydfil 16,291 (56%)

Sheffield 136,018 (51%)

A different set of areas outside of the South of England where people could vote can be used to compare every county in the South of England. In each and every case the electorate of the area in the South of England was lower, but the leave vote was higher. Click play below to hear the talk.

The Brexit Way: A walking route through the areas of the UK that supplied the majority of Leave votes despite having a minority of voters

April 23, 2019

Dying Quietly: The New Suburbs

Mustn’t grumble. Mustn’t make a fuss. England’s suburbs are slowly dying, as years of austerity slowly changes the landscape. Since 2014, life expectancy has been falling across most of England, especially in the suburbs. The elderly are now dying faster than before. And it is in the suburbs, far away from your children (if you had children), that you now much more often live and die alone.

The mantra that there is no such thing as society, just families and their children, rings both true and hollow in the suburbs.

The suburbs are changing more quickly today than they have changed in decades. The centres of cities are increasingly reserved for the young, the successful and those who can afford to avoid long commutes. Out of town villages are where the very affluent go when they age—the idyllic cottage in the country.

Rising economic inequality

In the great suburban new hope of the era from 1930 to 1970, the suburbs were supposed to be where life’s winners went. Suburban schools were ‘good’, suburban jobs were plentiful and well paid. Suburban doctors were not over‐worked; hospitals were accessible. But the money began to run out in the 1970s.

England accommodated its loss of empire by accepting rising economic inequality. After the 1970s the country as a whole became poorer in comparison with the rest of the developed world and with most of Europe, but in the 1980s, 1990s and noughties those at the top took a greater and greater share of the pie each year. As they did so they took more and more from the poor and from suburban middle England, from the places where the majority lived, the places that saw progress stall.

Today there are far fewer winners, so those fewer winners win much more. The semi‐detached three‐bedroom suburban house is now the place you end up in if you have not failed but also have not succeeded. The bills remain high, the council tax rises, the repairs have to be done. This is beginning to swing suburbs in the south of England towards Labour.

Suburban Conservative‐voting England, where the fewest immigrants arrive, is where UKIP did best in various votes before 2017. We try to pretend it is the poor council estates, the east coast and ‘the north’ where this dissatisfaction was greatest; but that is not where the sense of loss was strongest.

In 2007 the best‐off one per cent of people in the UK took 15.4 per cent of all income. The suburbs suffer the most from such inequality. In other European countries, where the one per cent take less, the poor do much better—but it is the suburbs that most benefit from greater economic equality. Compared with Scandinavian norms the best‐rewarded one per cent of people in the UK take enough extra to fund a second national health service.

The suffering of the suburbs

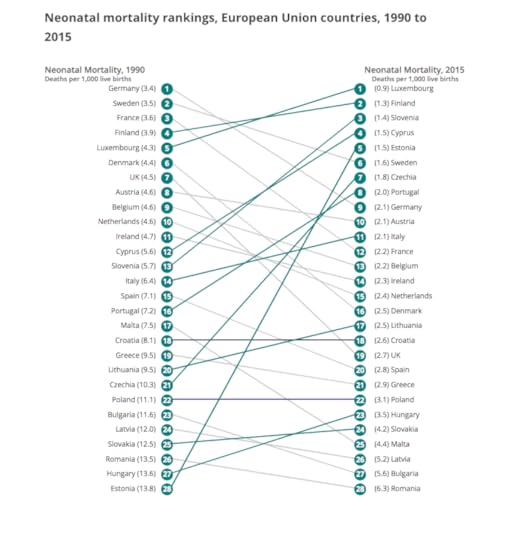

Between the censuses of 2001 and 2011 the number of people who had to resort to private renting in the UK doubled. The increases were greatest in the south‐east and especially within London. This was portrayed as a ‘buy‐to‐let revolution’ but it was led by landlords who owned multiple properties, not by ‘small investors’. And all the time living standards in the UK, especially in England, were falling in relation to those in the rest of Europe. This is illustrated most dramatically by the changed ranking in neonatal (first twenty‐eight days) mortality rates from 1990 to 2015 (see Figure 2).

Neonatal mortality rankings, European Union countries, 1990 to 2015

Figure 2: Neonatal mortality rates, EU countries, 1990–2015

The decline in living standards was felt most acutely in the suburbs. They are where more and more of the food banks are placed and the gas bills are not paid on time. From slowing improvements in infant mortality, through to declining school budgets, low wage work for the majority, the introduction of crippling student loans leading to precious jobs, and then paying the highest rents in Europe, the problems of the English were no longer concentrated in ‘those inner cities’.

Poverty rose faster in outer London than inner London. It is in southern England’s suburbs where poverty rose the most between the 2001 and 2011 censuses. So gradual and hidden was the rise that without a census it could not be seen.

When, in 2016 and early 2017 young adults in Britain looked at what was increasingly on offer, they began to balk at the unfairness of it all. Large numbers did not vote in the general election of 2015; Labour did not offer them much of an alternative then. Almost as many young adults did not vote in the referendum of 2016, for either side. Again, what was there for them to vote for? But come June 2017, their votes were against the landlords, against student fees, and against the decay of the suburbs that was increasingly looking like their fate.

….

The architecture of wealth extraction

Joe Brewer writes: “The architecture of wealth extraction is a cancer on this planet. It continually corrupts our governments, poisons the natural environment, and pits us against each other in a ‘race to the bottom’ that has only one logical outcome – the wholesale destruction of life‐giving capacities for the only home planet we’ll ever have.”

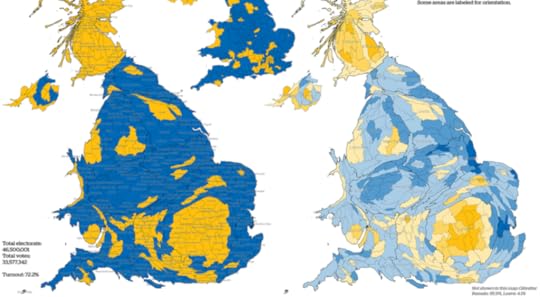

It was the suburbs that voted Brexit. Just look at the map and forget your preconceived prejudices. The map shows the pattern. If you want a modern day definition of suburb in England it could be: that part of the end of your town or city where the majority of people quietly, desperately and angrily voted to leave the EU as they felt on the edge.

Areas are shaded by whether a majority who voted voted to Leave or Remain and also by the proportions voting in these ways

Figure 3: The human geography of the EU referenced vote, 2016

The English and American suburbs are both quietly dying. They are no longer places of success, but have become places of social and political retreat (where people hark after ‘being great again’). The US vote for Trump was highest in those suburbs in which the health of Americans was declining most quickly.

What matters for this analysis is that the break occurred between 2015 and 2017. Before then the situation simply appeared to be worsening continuously. For example, mortality rates in the UK remained high in 2016 and among the elderly peaked again in early 2017. What was most shocking was how little attention this received. It is as if we now expect it. But as the June 2017 UK election result showed, people had begun to notice and to react. As I write (in May 2018) support for Corbyn’s Labour party still lies at 38 per cent of all voters—as it did in June 2017.

The revolt of the suburbs: Brexit

The old party of the suburbs were the Conservatives. Their suburban grip remains strong but was then weakened by UKIP. Today most of the UKIP vote, built from suburban discontent, has returned to the Tories. Today, they now offer Brexit as suburban salvation. Like Trump, they will now build a wall to stop more migrants, but it will be an invisible electronic wall of visa restrictions and entitlements reduced. This, they promise, will ‘make Britain great again’.

We sold dear to the empire and brought cheap from it. Those days are gone. Failure to replace the empire with an alternative, while allowing the one per cent to take more and more, is what has been killing suburbia.

In the US and the UK, the architecture of wealth creation has been allowed to take a particular form which is now harming the wellbeing of the majority, especially the young. This is why suburbia is now suffering.

All across England, suburbs are changing from places of aspiration to neighbourhoods where many can be frightened into voting to ‘take back control’. But the suburbs need to be recaptured by the young. If the next generation is to settle down and have children in the suburbs then they need to win those suburbs back—politically—from the landlord and the ideology of let the Devil take the hindmost.

…

This blog is adapted from a longer piece in the Political Quarterly journal:

DANNY DORLING

Danny Dorling is a British social geographer and is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography of the School of Geography and the Environment of the University of Oxford.

click here to read more, for the link to the journal website and for a PDF of this article.

April 15, 2019

The Wreckers: Fabian Review Essay, Spring 2019

The crises which have engulfed this government should not blind us to the fact that the Conservatives are supremely successful at what they are best at.

The Wreckers

Danny Dorling

As a child I used to make sandcastles whenever I could get to a beach, which was usually just once a year in the summer. The beach was most often in Wales: Whitesands bay, on St David’s head. It is a very good beach for making castles. The sand is just about the right texture and there is a clean stream. During the summers of the 1970s, hundreds of families would camp in the valley above the beach. They still do today. Each morning the children would run down to the sea. And there, newly cleaned by the tide, was a flattened beach upon which to build new sandcastles.

It takes a certain degree of competence to make a good sandcastle. To make a great sandcastle requires much more than that. It requires teamwork. No single child working on their own can make a series of sandcastles on a beach that people stop and stare at in wonder and say: “How were they ever made to look like that?” Often a few adults, secretly wishing they were still children, will have played a part (it helps to have some bigger spades). But for the best results, to build a sand sculpture of hundreds of small castles and outbuildings, with the stream winding through them and much else besides – and to do this all before the tide comes in – requires great cooperation with many other builders and the spreading of competence as children learn from each other.

Very occasionally there was a child who did not like to share, or a small group of such children egging each other on, and they would wait until no one was looking and then try to knock the castles down. I never really understood their motivation, why they felt the need to destroy, why they hated what so many others had made by working well together. But, in just a few minutes, a tiny few could destroy what it had taken a much larger number of others to build up over many hours. Smirking and for some odd reason satisfied, the wreckers would leave a wasteland behind.

As I grew up and watched the Conservatives tear down so much of the industry of Britain, so much of the welfare state, and so much solidarity, I was often reminded of the look on the faces of some of those aberrant, angry, antisocial children. It was hard to work out what might drive someone to take apart what others have so carefully built up in a society and to replace it with nothing but a wasteland. What pleasure could you get from doing that? And then I began to realise that they thought they were actually making something through their destruction. They were showing that cooperation was folly. And they were convincing themselves at least that they were more powerful and more successful; destined to have their way.

Essentially, their policies promote division, competition and fear in place of the norms of cooperation and coordination of provision we see elsewhere in Europe. And yet, they have a reputation for competence, for being ‘a pair of safe hands’ as it were, and continue to do so in spite of the chaos that we can see all around us today. So, while the U-turns, the bungled general election in 2017 and the mishandling of Brexit certainly display incompetence, attempts to portray the Conservatives as such ignore the party’s undeniable success.

The Conservatives in Britain are the most successful right of centre party in Europe, not just in having been in power so many times and for so long, but in having successfully pursued the most right-wing agenda of any mainstream European party. During the 1980s and 1990s they succeeded in changing hearts and minds. They were to transform the UK from being one of the most equitable countries in all of the continent in the 1970s, to the country which now consistently tops the OECD league table for income inequality in Europe. A league table shift of such great magnitude does not happen by accident.

For a time, the Conservatives succeeded in deflecting Labour away from seeing issues such as inequality as so crucial. Only a decade or so ago, the huge disparity between the super-wealthy and the rest was portrayed by key Labour figures as “not a great problem, so long as the rich pay their taxes”.

On education too, the Conservatives have been remarkably successful in shifting the parameters of the debate. In no other European country is so much money spent to give an unfair advantage to such as small number of children as the money spent on private schools in the UK. In every area of social life, Conservatives promote evaluative voluntary individualist logic as the alternative to generous omnipresent ordered delivery. On their watch, pre-school education became a private business opportunity; state schools were progressively underfunded and selection at age 16 was introduced via academies.

They have continued to prioritise grammar schools because each grammar school creates so many losers for each winner. Their mentality assumes that only a few can win and most people deserve to be losers; grammar schools are especially dangerous because they imply that the future winners can be identified in early childhood through a test! The Conservatives repeatedly decimate further education and have turned higher education into a marketplace with loans for the many and free entry for the few. Those few who now go to university essentially for free are mostly their own children who will emerge with no student debt thanks to their affluent parents paying their fees upfront.

On housing, the Conservatives have determinedly destroyed – through right to buy, stock transfers and a lack of funding – much of our social provision. One in four children in England now lives in a home from which they can be evicted with just two months’ notice at the whim of their private landlord. Conservatives fix the housing market, constantly intervening in it to prop it up. George Osborne’s various ‘help-to-buy’ schemes now leave future governments with the most enormous financial liability should house prices fall by more than 5 per cent (a relatively mild scenario given that Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has predicted falls of 30 per cent could be possible). Those schemes were introduced to mask what was happening to the majority who could never get a mortgage to buy a home. Osborne’s measure of success was house prices. The higher they were, the better he thought he was doing.

On health, Conservatives succeeded in moving the UK from being one of the best ranked in the world in the 1960s and 1970s through to one of the worst countries in Europe for health outcomes after their period of hegemony. The UK used to have one of the very best rates of child health in the world. However, by 1990, following 11 years of Tory underfunding, six countries in Europe had lower neonatal mortality rates than the UK, but that was just the start of the decline. By 2015 the UK ranked 19th for neonatal mortality across Europe. Most recently the situation has become far worse, as infant mortality in the UK has risen year after year from 2015 onwards. Nowhere else in Europe has it risen. Similarly, but for separate reasons, overall life expectancy across the UK peaked in 2014 and has fallen since. Again, nowhere else in Europe has a record of change as bad as this. And again, such an extreme record does not happen by chance. It requires a huge amount of work to shift a country from being so successful in terms of comparative health outcomes, to so unsuccessful over such a short space of time. They are indeed competent – at making life much worse for most people.

How should Labour respond? How do you respond to wreckers who have such a different view of what is right and fair and decent?

Labour’s answer on education is to offer a National Education Service, which is laudable, but which has echoes of the 1940s in its title, implying that Whitehall operating benignly from above will somehow create a situation in which your child – and since the 1980s it’s all about ‘you and your family’ – will prosper. If it’s all about you and if you don’t have children, or if you have the money to live in the good catchment area, or send your children private, then evaluative voluntary individualist logic tells you to vote Tory. In fact, for your children to get ahead, you need less spent on the education of the ‘competitor’ children or grandchildren. A very large minority of the British population have been taught not to share well in recent decades. Because of this it is perhaps not surprising then that in 2019, around 40 per cent of adults have still been saying in opinion poll after opinion poll they are happy to lend their support to the Conservatives.

In the face of Tory individualist logic, Labour needs to be far bolder. Working with Michael Davies recently I wrote a paper for the Progressive Economy Forum titled Jubilee 2022: Writing off the student debt. In it we explained why it was both right and practical for Labour to include a promise in the next election manifesto to cancel the vast majority of outstanding university student debt for all those students who went to university in 2012 or thereafter. The policy makes good economic sense as well as being fair. And, in a country where half of all young women now go to university, and where people have been made to think so individualistically, it also makes brilliant political sense. Almost everyone who went to university between 2012 and 2018, and those who will go in 2019, 2020 and 2021 (and those thinking of going in future, and their families) would have an obvious extra incentive to vote Labour at the next general election – as would their parents and grandparents – but only if Labour promises to cancel most of the outstanding unfair debt.

We don’t just need to unravel the recent errors of Conservatives. That is just a first step to make a promise that if you vote Labour it will be as if the introduction of £9,000 a year fees by David Cameron and Nick Clegg never happened. Labour also need to offer something so much more enticing than a ‘national service’. I have many ideas, but so do you, and so do many others. You don’t build a good set of sand castles on the beach alone; and you always have to be wary for those who would try to destroy what you have made. Jubilee 2022: Writing off the student debt is a small castle that I built recently with Michael and the help of a few other experts on student finance, I’m quite proud of it. Would you like to make a castle to go next to it? Perhaps suggest a better pre-school policy or housing policy, to add to all the beautiful landscape of all the proposals that are already being suggested?

On housing, Labour has to stop being polite. Conservative policies are taking a huge human toll. In early 2019, as the head teacher of what had been Marston Middle School in Oxford in the 1980s, Roger Pepworth, explained so clearly after the death of a former pupil who had most recently slept rough on the streets of Oxford: “I do not have solutions. I only know that the dreams that Sharron, a lovely child, had until her death, have perished in the wreckage of an austerity programme that has literally killed her and her like.”

Sharron’s death will not be forgotten in Oxford for a long time to come. Decades ago the Conservatives dismantled the social provision that, had it been in place, could have helped Sharron when she was a young girl in the 1980s. The Tories ensured later that when Sharron most needed help as an adult, it was not there. Millions live in fear of how they will pay the rent or cope with the mortgage payments. Millions more live with the misguided belief that the homes they own are worth a fortune now and will fund a luxury retirement for them (as long as they keep voting Conservative). But top Tories don’t have mortgages. They buy and sell in cash and have property around the world – they dupe other people into voting for their party. Top Tories care not one jot that homelessness rises when they are in power.

In the UK today, even just within London, we still have more bedrooms within residential homes than there are people who need a bed. We have not built enough where the need is great enough; but the fastest way in which we will better house ourselves again is to repeat what we did for the whole period from 1921 to 1981; for those 60 years, each year, we better used the stock we had than the year before. We built more but more importantly each year we shared better. Growing income equality meant that the rich did not buy second homes so often. People increasingly moved into housing of the size their families needed; and a third of all housing was allocated on the basis of need, not greed. History will repeat, but the mechanism will be different in future. On Whitesands Bay each summer today new and different sandcastles are being built with each new tide.

The solution for all of our public services in future will not be a return to the 1970s. That tide went out long ago, and many tides have come in since to wash the solutions of those days away. Just like social policy of the past, new castles are made of sand, they always melt into the sea – eventually. You just have to keep on building more. The better health system of the future will not simply be a return to what we had before the 2012 privatisation act. To be better, it has to be different.

For the last four decades, there have been more social wreckers on the policy beach than social builders, but that time has ended: evaluative voluntary individualist logic has had its day. The alternative of generous omnipresent ordered delivery is becoming more obviously and urgently viable again. Well ordered, for everyone, delivered to time, to where there is most need, and generous, not skimping. Achieving this will mean more investment, but it will also mean more ideas and above all more cooperation. For too long a party with a reputation for competence has been trusted with our social fabric and services. Those politicians who, as teenagers, joined the Conservative party in the late 1970s and 1980s did so because they admired Mrs Thatcher’s policy of wrecking – so-called ‘creative destruction’. They are and were very competent, but only at breaking things – we must ensure they are never trusted again.

Danny Dorling is a professor of geography at the University of Oxford. His book A Better Politics was published in 2016 and is available to download free. Most recently he published ‘Rule Britannia: from Brexit to the end of empire’ in cooperation and collaboration with Sally Tomlinson

The Wreckers, Fabian-Review-Spring-2019 / Fabian Review Essay, Volume 131, No. 1, pp. 21-23.

For a PDF of the article click here.

A Drip Sand Castle – It’s easy if you try.

Day of reckoning: Brexit and UK Universities

Universities helped foster the environment in which Brexit became possible. It is time to make amends.

The UK’s higher education system helped create the Brexit mess. We taught the politicians who have led the debacle. We sat back and watched as the nations of the UK became ever more socially and economically divided from the 1980s onwards. We benefited from the growing fear that without a university degree your child would be consigned to a life of low pay and drudgery.

Those who ran our universities took more and more for themselves—arguing that they were now running large businesses and so deserved to be handsomely rewarded. We provided succour to the belief that Britain could “go it alone” with our endless press releases about all the incredible innovations our universities were fostering, which would soon result in so many new companies and new jobs being created.

We lapped up ridiculous university rankings that proclaimed our “leading institutions” were among the very best in the world, and by doing so we helped spread the message that the UK was so very great that it could take back control and ascend again to its rightful place astride the world stage. We—if we stand back and take a long, hard look at ourselves—have become a large part of the problem.

Read the rest of this article by Danny Dorling in Research Fortnight, first published April 14th 2019.

Who cut that lawn so nicely?

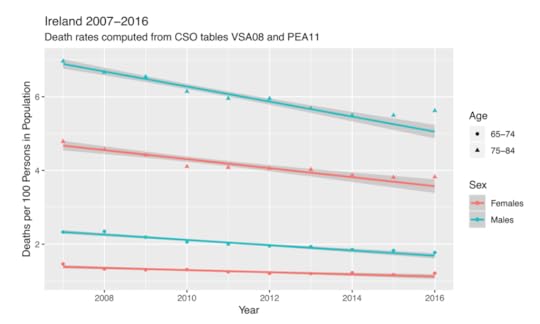

Ireland: Recession, Austerity and Life Expectancy

Dear Sir

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the letter of February 25, 2019 from Professor J Hanley. This refers to our short paper on “Recession, Austerity and Life Expectancy” published in the Irish Medical Journal in February 2019. We should like to make the following comments

(i) Prof. Hanley begins by stating: “… the article accurately depicts the slowing down of improvements in life expectancy worldwide”.

We do not make any claims on the worldwide trend in life expectancy. However, it may be useful to know that the most recent estimate given by the World Bank for global life expectancy for both men and women combined is 73 years and two weeks. There has not been a slowdown in the worldwide rise in life expectancy in recent years, in fact a slight acceleration has taken place since a slowdown that did occurred in the years immediately prior to 1995. [1]

(ii) Prof. Hanley further states that the article “misrepresents the actual pattern of death rates”. The article doesn’t present death rates.

(iii) Prof. Hanley suggests that for Ireland we gave the “mistaken impression that mortality rates have risen since 2008.”

We did not state that mortality rates had risen as we did not analyse mortality rates. However, the data he provides show that, for men aged 75-84 in Ireland, there was an obvious rise in the most recent year. We are remiss in not having made more of that and perhaps should have looked at death rates as well as both life expectancy and the deviation form the number of expected deaths that has occurred. However we did show, in Table 1, that 4.4% more men were dying in this age group than would have been expected had the recent trends in life expectancies continued.

We do acknowledge that there could be some confusion in our text using “rates” to refer to the rate of excess as a percentage of all deaths that have occurred.

(iii) Prof. Hanley said that it is unfortunate that the media reported as a “spike” the even greater departure for the trend that we reported for women in Ireland. We have no control over the media reporting of our work, or of the journalists’ interpretations.

(iv) Prof. Hanley provides his own graph. We feel it is important to be able to compare like with like i.e. to explore the most recent years in the context of trends from the previous years (albeit in our work, which was on life expectancy and the absolute number of deaths). We have therefore superimposed lines of best fit for the years 2007 to 2014. The lines certainly show a downward trend in mortality rates, but for 2015 and 2016 the data points, particularly for males aged 75-84, are some way above this trend, which is one of the main points our paper tried to make. We hope this reply helps to strengthen that point. Something unusual is occurring in Ireland.

Ireland 2007-2016: Death rates by age and sex

Reference [1] Source: World data life expectancy data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/... (accessed 30th March 2019).

Yours faithfully

Danny Dorling Jan Rigby Christopher Brunsdon

read more here

April 14, 2019

Peak Inequality: a public lecture by Danny Dorling

There’s no reason to be pessimistic about the future. The UK and the USA are probably at a peak of economic inequality right now. Income inequality will almost certainly reduce in the years and decades to come; decade after decade after decade. And we will slowly learn what most other people in the rich world know, that having more and more money doesn’t make you happier; it doesn’t make your country more sustainable; and it doesn’t solve the problems of the planet.

A public lecture by Danny Dorling, about the book ‘Peak Inequality‘, open to all and organised by Shipley Constituency Labour Party. Held in the Queens Hall, Burley in Wharfedale, on April 13th 2019:

Peak Inequality: Britain’s ticking time bo

mb

April 7, 2019

Britannia, Brexit and what now in the week before the April 12th deadline?

Danny Dorling speaking at the Cambridge Literary Festival, introduced by Cathy Moore, in the Palmerston Room, St John’s College, University of Cambridge, April 6th 2019 (the image shown here is of a protestor standing on one of the pillars of the gates of Blenheim Palace in 2018).

A protestor standing on one of the pillars of the gates of Blenheim Palace in 2018.

As Sally Tomlinson and Danny Dorling wrote, in 2018, within book “Rule Britannia” that was published on 15th January 2019:

“Whatever kind of Brexit occurs – hard, soft, or even a cancellation and staying in the European Union – Britain will be much diminished by the Brexit process. Already the British have lost face in a multitude of small ways. More additional money had to be found to pay for Brexit in the November 2017 Budget than could be found for the NHS.8 On the same day as that Budget, we also learnt that Britain would lose its special place on the International Court of Justice for the first time since the court’s inception in 1946.

The arguing and making of claims and counter-claims about its national status has not improved the image of Britain in the eyes of much of the rest of the world But there is an upside. The British may well learn a great deal about themselves as a result of what they are going through. Not least that Britain, and even Brexit, has its deepest roots embedded firmly in the ashes of the British Empire.”

To listen to talk click the arrow below:

And for more on the book that the talk is based on click here.

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers