Danny Dorling's Blog, page 15

May 20, 2020

The illusion of speed and growth in our society

Danny Dorling, and Sofie Furu discussing the Book Slowdown and the illusion of speed and growth in our society, an on-line talk held with SoCentral – nordisk inkubator for samfunnsinnovasjon, Oslo, Norway, May 20th 2020.

The slowing down snail

May 18, 2020

Put your foot on the brake

The rate of population growth is slowing – and it’s time for human activity to relax too. It’ll do our species so much good, says Danny Dorling.

Big Issue Magazine Illustration

Outside the brief periods of population decline in wartime and pandemic, population growth rates have exceeded one per cent every year since 1901. However, according to the latest UN estimates they will now almost certainly fall below that level by 2023, then quickly drop to below 0.9 per cent annual growth around the year 2027, and then fall not quite as rapidly. The current pandemic is unlikely to alter these figures. By late April, approaching 0.003 per cent of the population of the world had died due to Covid-19.

If the numbers we collect about ourselves could speak, perhaps they would say: “We have given you all the information we have and given you all the options; if you humans don’t slow down, you are finished.” We should now mostly know what we have to do and what resources we have to do it with. There is no sudden ship of technological marvels about to appear over the horizon to save us.

The big economic wheel keeps turning and its central axis is moving, but a slower set of gears is engaging and soon it will slow to a stop, even reverse. Disaster capitalists – those who came to believe in the cult of creative destruction – hate not having a choice to continue as we are. But we don’t.

Although we don’t know for sure what will happen between now and peak human (the day after which the total number alive begins to slowly fall), we can now work out what can’t happen. When the capitalist transition began, we believed that the world was at the centre of the universe. As the transition accelerated, we learned that there might not be a god or gods. Each generation had so much to learn.

Hopefully, in future, we will no longer have to wind down simply to cope with having become so wound up

When the capitalist transition started there was no single key economic centre to the world and there will very likely be no single key centre when the transition ends. We should not concern ourselves with what country will be hegemonic in future. We don’t have to worry about whether Beijing will take over from London and New York. Such questions are questions of the past; questions that mattered greatly at the height of the age of transition.

Today the shock is not change. The shock is when the change stops. When the cranes are taken down, and we are building mostly to repair and renew what we first built a long time ago. The shock is that we are no longer expanding, and no longer seeing a geographical shift to a single new centre of dominance. However, as we adapt to slowdown, we may not sense that our pace of change is slowing.

Everything is relative. Even the feeling of time passing is relative. When you are young, your summer holidays feel like they go on forever. When you are old, you wonder where all the time went and why birthdays come around so quickly. No wonder we cannot easily see that slowdown is occurring. And just as we find it hard to understand change, so too will we find it hard to understand a state of very little change – until it becomes normal, until the stories we tell fit the times we experience.

Hopefully, in future, we will no longer have to wind down simply to cope with having become so wound up. We do not know what will happen, but to achieve a better future we must first imagine it. Slowdown means the end of rampant capitalism. It never could last forever, based as it was on the expectation of continually expanding markets and insatiable demand, and its creation of a bizarre concentration of wealth that has made a mockery of democracy.

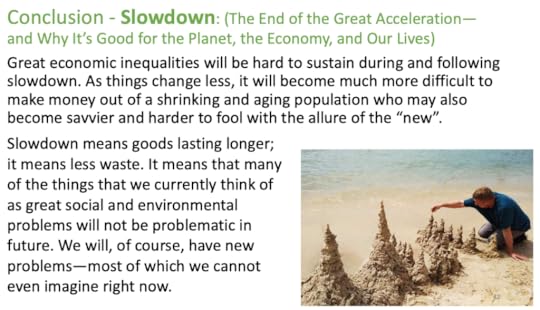

Slowdown means goods lasting longer; it means less waste

Great economic inequalities will be very hard to sustain during and following the slowdown. As things change less, it will become much more difficult to make money out of a shrinking and ageing population who may also become savvier and harder to fool with the allure of the ‘new’ – as well as the world’s gold or its fine pearls. Most advertising aims to persuade us that we want what we do not need; we must buy it, or at the very least covet it and despair if we cannot even dream of having it. However, now that more and more people study psychology and the social sciences and have greater numeracy skills, fooling the majority will become harder and harder to achieve.

Slowdown gives us time to worry more about one another and less about what we will ourselves receive in future. Slowdown means more time to question all that our grandparents never had time to question, because they were dealing with so much that was new.

Slowdown means goods lasting longer; it means less waste. It means that many of the things that we currently think of as great social and environmental problems will not be problematic in future. We will, of course, have new problems – most of which we cannot even imagine right now. And we will, of course, do things we have always done, things that right now we long for.

Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration – and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives by Danny Dorling is out now.

For a PDF of this article and a link to the original posting click here.

May 14, 2020

Uniting Behind A People’s Vaccine Against COVID-19

As reported in the Financial Times; Le Monde; News Week Españo and many others, an open letter: Uniting Behind A People’s Vaccine Against COVID-19, May 14th 2020 signed by Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, Imran Khan, Cyril Ramaphosa and many others, organised by Oxfam:

Humanity today, in all its fragility, is searching for an effective and safe vaccine against COVID-19. It is our best hope of putting a stop to this painful global pandemic.

We are calling on Health Ministers at the World Health Assembly to rally behind a people’s vaccine against this disease urgently. Governments and international partners must unite around a global guarantee which ensures that, when a safe and effective vaccine is developed, it is produced rapidly at scale and made available for all people, in all countries, free of charge. The same applies for all treatments, diagnostics, and other technologies for COVID-19.

We recognize that many countries and international organizations are making progress towards this goal, cooperating multilaterally on research and development, funding and access, including the welcome $8 billion pledged on 4th May. Thanks to tireless public and private sector efforts and billions of dollars of publicly-financed research, many vaccine candidates are proceeding with unprecedented speed and several have begun clinical trials.

Our world will only be safer once everyone can benefit from the science and access a vaccine — and that is a political challenge. The World Health Assembly must forge a global agreement that ensures rapid universal access to quality-assured vaccines and treatments with need prioritized above the ability to pay.

It is time for Health Ministers to renew the commitments made at the founding of the World Health Organization, where all states agreed to deliver the “the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being”.

Now is not the time to allow the interests of the wealthiest corporations and governments to be placed before the universal need to save lives, or to leave this massive and moral task to market forces. Access to vaccines and treatments as global public goods are in the interests of all humanity. We cannot afford for monopolies, crude competition and near-sighted nationalism to stand in the way.

We must heed the warning that “Those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” We must learn the painful lessons from a history of unequal access in dealing with disease such as HIV and Ebola. But we must also remember the ground-breaking victories of health movements, including AIDS activists and advocates who fought for access to affordable medicines for all.

Applying both sets of lessons, we call for a global agreement on COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics and treatments — implemented under the leadership of the World Health Organization — that:

1. Ensures mandatory worldwide sharing of all COVID-19 related knowledge, data and technologies with a pool of COVID-19 licenses freely available to all countries. Countries should be empowered and enabled to make full use of agreed safeguards and flexibilities in the WTO Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health to protect access to medicines for all.

2. Establishes a global and equitable rapid manufacturing and distribution plan — that is fully-funded by rich nations — for the vaccine and all COVID-19 products and technologies that guarantees transparent ‘at true cost-prices’ and supplies according to need. Action must start urgently to massively build capacity worldwide to manufacture billions of vaccine doses and to recruit and train the millions of paid and protected health workers needed to deliver them.

3. Guarantees COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics, tests and treatments are provided free of charge to everyone, everywhere. Access needs to be prioritized first for front-line workers, the most vulnerable people, and for poor countries with the least capacity to save lives.

In doing so, no one can be left behind. Transparent democratic governance must be set in place by the WHO, inclusive of independent expertise and civil society partners, which is essential to lock-in accountability for this agreement.

In doing so, we also recognize the urgent need to reform and strengthen public health systems worldwide, removing all barriers so that rich and poor alike can access the health care, technologies and medicines they need, free at the point of need.

Only a people’s vaccine — with equality and solidarity at its core — can protect all of humanity and get our societies safely running again. A bold international agreement cannot wait.

Signed:

Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo — President of the Republic of Ghana

Imran Khan — Prime Minister of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

Cyril Ramaphosa — President of the Republic of South Africa and Chairperson of the African Union

Macky Sall — President of the Republic of Senegal

Karen Koning Abuzayd — Commissioner of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry for Syria, Under Secretary-General as UNRWA Commissioner-General (2005–2010)

Maria Elena Agüero — Secretary General, World Leadership Alliance-Club de Madrid

Esko Aho — Prime Minister of Finland (1991–1995)¹

Dr. Shamshad Akhtar — Former UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

Rashid Alimov — Secretary General, Shanghai Cooperation Organization (2016–2019), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Tajikistan (1992–1994)²

Amat Alsoswa — Former Yemen’s Minister for Human Rights, Former United Nations Assistant Secretary General, UNDP Assistant Administrator and Regional Director/ Arab States Bureau

Philip Alston — John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law, New York University School of Law and Former UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights

Baroness Valerie Amos — United Nations Undersecretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator (2010–2015)

Rosalia Arteaga Serrano — President of Ecuador (1997)²

Maria Eugenia Brizuela de Avila — Minister of Foreign Affairs of Salvador (1999–2004)

Shaukat Aziz — Prime Minister of Pakistan (2004–2007), former VP of the Citibank²

Jan Peter Balkenende — Prime Minister of The Netherlands (2002–2010)¹

Joyce Banda — President of the Republic of Malawi (2012–2014) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation¹

Nelson Barbosa — Professor, FGV and the University of Brasilia, and former Finance Minister of Brazil

José Manuel Barroso — Prime Minister of Portugal (2002–2004), President of the European Commission (2004–2014)¹

Carol Bellamy — Former Executive Director, UNICEF (1995–2005)

Valdis Birkavs — Prime Minister of Latvia (1993–1994)¹

Irina Bokova — Director-General of UNESCO (2009–2017)

Gordon Brown — Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2007–2010)

Winnie Byanyima — Executive Director of UNAIDS and UN Under-Secretary General

Kathy Calvin — Former Chief Executive Officer of the United Nations Foundation

Kim Campbell — Prime Minister of Canada (1993)¹

Fernando Henrique Cardoso — President of Brazil (1995–2003)¹

Gina Casar — Executive Director of AMEXCID, Associate Administrator of UNDP (2014–2015)

Hikmet Cetin — Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey (1991–1994), former Speaker of the Parliament²

Ha-Joon Chang — Director, Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge

Judy Cheng-Hopkins — Former Assistant Secretary-General, Peacebuilding Support, United Nations

Laura Chinchilla — President of Costa Rica (2010–2014)¹

Joaquim Chissano — President of the Republic of Mozambique (1986–2005) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation¹

Helen Clark — Prime Minister of New Zealand (1999–2008), UNDP Administrator (2009–2017)¹²

Emil Constantinescu — President of Romania (1996–2000)²

Radhika Coomaraswamy — former UN Under Secretary General and The Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict

Ertharin Cousin — Executive Director of the United Nations World Food Programme (2012–2017)

Paula A. Cox — Premier of Bermuda (2010–2012)

Herman De Croo — Minister of State of Belgium; Honorary Speaker of the House²

Olivier De Schutter — Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights

Danny Dorling — Professor of Human Geography at Oxford University

Ruth Dreifuss — President of Switzerland (1999) and Federal Councillor (1993–2002)

Diane Elson — Emeritus Professor University of Essex, Member of UN Committee for Development Policy

Maria Fernanda Espinosa — President of the United Nations General Assembly (2018–2019), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador (2007–2009, 2017–2018) and Member of the Political Advisory Panel of UHC2030

Moussa Faki — Chairperson of the African Union Commission

Christiana Figueres — Executive Secretary of UNFCCC (2010–2016)

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir — President of Iceland (1980–1996)¹

Louise Fréchette — UN Deputy Secretary-General (1998–2006)

Sakiko Fukuda-Parr — Director of the Julien J. Studley Graduate Programs in International Affairs and Professor of International Affairs at The New School

Patrick Gaspard — Former United States Ambassador to South Africa, President of the Open Society Foundations

Jayati Ghosh — Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University

Felipe González — President of the Government of Spain (1982–1996)¹

Rebeca Grynspan — Vice President of Costa Rica (1994–1998), Ibero-American Secretary General

Alfred Gusenbauer — Chancellor of Austria (2007–2008)¹

Han Seung-Soo — Prime Minister of the Republic of Korea (2008–2009)¹

Noeleen Heyzer — Member of the UN Secretary-General’s High Level Advisory Board on Medication²

Mladen Ivanic — President of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2014–2018)²

Devaki Jain — Feminist economist, Honorary Fellow at St Anne’s College, Oxford and member of the erstwhile South Commission (1987–90)

Arjun Jayadev — Professor of Economics at Azim Premji University

Rob Johnson — President of the Institute for New Economic Thinking

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf — President of the Republic of Liberia (2006–2018)¹

Mehdi Jomaa — Prime Minister of Tunisia (2014–2015)¹

Anthony T. Jones — Vice-President and Executive Director of Gorbachev Foundation of North America (GFNA)¹

Ivo Josipovic — President of Croatia (2010–2015)²

Naila Kabeer — Professor of Gender and International Development at the London School of Economics

Michel Kazatchkine — Special Advisor to the Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS (UNAIDS) in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and Senior Fellow, Global Health Center, the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva

Rima Khalaf — President of the Global Organization against Racial Discrimination and Segregation, and Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2010–2017)

Horst Köhler — President of Germany (2004–2010)¹

Jadranka Kosor — Prime Minister of Croatia (2009–2011)²

Bernard Kouchner — Minister of Health of France (1992–1993, 1997–1999, 2001–2002), Minister of Foreign affairs of France (2007–2010); founder of Médecins sans frontiers / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and Médecins du Monde / Doctors of the World (MdM)

Chandrika Kumaratunga — President of Sri Lanka (1994–2005)¹

Aleksander Kwaśniewski — President of Poland (1995–2005)¹²

Rachel Kyte CMG — Dean of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University

Luis Alberto Lacalle Herrera — President of Uruguay (1990–1995)¹

Ricardo Lagos — President of Chile (2000–2006)¹

Zlatko Lagumdzija — Prime Minister of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2001–2002)¹²

Laura Liswood — Secretary General of the Council of Women World Leaders

Nora Lustig — President Emerita of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association, Professor of Latin American Economics, Tulane University

Jessie Rose Mabutas — Executive Board Member, African Capacity Building Foundation, Expert Member, Accreditation Panel of the UN Adaptation Fund, and Executive Board Member, Section on African Public Administration of the American Society for Public Administration

Graça Machel — Founder, The Graça Machel Trust and Foundation for Community Development

Susana Malcorra — Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina (2015–2017)

Isabel Saint Malo — Vice President of Panama (2014–2019)

Purnima Mane — Global expert on gender, HIV and sexual and reproductive health issues, President of Pathfinder International (2012–2016)

Mariana Mazzucato — Professor at University College London and Founding Director of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP)

Mary McAleese — President of Ireland (1997–2011)

Rexhep Meidani — President of Albania (1997–2002)¹²

Carlos Mesa — President of Bolivia (2003–2005)¹

Branko Milanovic — Visiting Presidential Professor at the Graduate Center City University of New York

Aïchatou Mindaoudou — United Nations’ Special Representative for Côte d’Ivoire and Head of the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (2013–2017)

Festus Mogae — President of the Republic of Botswana (1998–2008) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation¹

Mario Monti — Prime Minister of Italy (2011–2013)¹

Kgalema Motlanthe — President of the Republic of South Africa (2008–2009) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation

Rovshan Muradov — Secretary General, Nizami Ganjavi International Center

Cristina Narbona — First Vice President of the Spaniard Senate and former Minister of the Environment of Spain

Bujar Nishani — President of Albania (2012–2017)²

Dr. John Nkengasong — Director of African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

Olusegun Obasanjo — President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999–2007) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation¹

Djoomart Otorbayev — Prime Minister of Kyrgyzstan (2014–2015)²

Roza Otunbayeva — President of Kyrgyzstan (2010–2011)¹

Ana Palacio — Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain (2002–2004)

Dr. David Pan — Executive Dean, Steve Scwarcman College, Tsinghua University China²

Flavia Pansieri — Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights (2013–2015)

Elsa Papademetriou — former Vice President of the Hellenic Republic (2007–2009)²

Andres Pastrana — President of Colombia (1998–2002)¹

Muhammad Ali Pate — Global Director, Health, Nutrition and Population Global Practice of the World Bank and Director of Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents

Kate Pickett — Professor of Epidemiology at the University of York

Thomas Piketty — Professor of Economics at the Paris School of Economics and a co-director of the World Inequality Database

Rosen Plevneliev — President of Bulgaria (2012–2017)²

Hifikepunye Pohamba — President of the Republic of Namibia (2005–2015) and Champion for an AIDS- Free Generation

Karin Sham Pòo — Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF (1987–2004)

Achal Prabhala — Coordinator of the AccessIBSA project

Dainius Puras — Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health

Iveta Radicova — Prime Minister of Slovakia (2010–2012)¹

José Manuel Ramos-Horta — President of Timor Leste (2007–2012)¹

J.V.R. Prasada Rao — Special Envoy to the Secretary General of the UN on AIDS (2012–2017) and Health Secretary of the Government of India (2002–2004)

Geeta Rao Gupta — Executive Director of the 3D Program for Girls and Women and Senior Fellow at the United Nations Foundation

Oscar Ribas — Prime Minister of Andorra (1982–84; 1990–94)¹²

Mary Robinson — President of Ireland (1990–1997), UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Chair of the Elders

Dani Rodrik — President-Elect of the International Economic Association, Professor of International Political Economy, Harvard University

Petre Roman — Prime Minister of Romania (1989–1991)¹

Juan Manuel Santos — President of Colombia (2010–2018), 2016 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Member of the Elders and Conservation International Arnhold Distinguished Fellow

Kailash Satyarthi — Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (2014) and Child Rights Activist

Ismail Serageldin — Co-Chair Nizami Ganjavi International Center, Senior VP of the World Bank (1992–2000)²

Fatiha Serour — Africa Group for Justice & Accountability

Michel Sidibé — Minister of Health and Social Affairs of Mali

Mari Simonen — Former Assistant Secretary General of the UN and Deputy Executive Director of UNFPA

Pierre Somse — Minister of Health and Population of Central Africa Republic

Vera Songwe — Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations and Executive Secretary, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

Michael Spence — Nobel Laureate for Economic Sciences (2001), William R. Berkley Professor in Economics & Business, NYU

Joseph E. Stiglitz — a Nobel laureate in economics and University Professor at Columbia University

Eka Tkeshelashvili — Deputy Prime Minister of Georgia (2010–2012)²

Aminata Touré — Prime Minister of Senegal (2013–2014)¹

Danilo Türk — President of Slovenia (2007–2012)¹

Cassam Uteem — President of Mauritius (1992–2002)¹

Marianna V. Vardinoyannis — Goodwill Ambassador of UNESCO²

Ann Veneman — Executive Director of UNICEF (2005–2010)

Chema Vera — Executive Director (Interim) of Oxfam International

Melanne Verveer — United States Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues (2009–2013), Executive Director of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security at Georgetown University

Vaira Vike-Freiberga — President of Latvia (1999–2007), Co-Chair Nizami Ganjavi International Center

Filip Vujanovic — President of Montenegro (2003–2018)²

Margot Wallström — Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sweden (2014–2019)

Richard Wilkinson — Emeritus Professor of Social Epidemiology, University of Nottingham Medical School

Kateryna Yushchenko — First Lady of Ukraine (2005–2010)²

Viktor Yushchenko — President of Ukraine (2005–2010)²

José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero — President of the Government of Spain (2004–2011)¹

Valdis Zatlers — President of Latvia (2007–2011)²

Ernesto Zedillo — President of Mexico (1994–2000)¹

Gabriel Zucman — Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley

¹ Member of WLA Club de Madrid

² Member of Nizami Ganjavi International Center (NGIC)

As reported by David Pilling and Andrew Jack in the Financial times on Thursday May 14th 2020

April 30, 2020

It’s Captain Tom’s birthday: the past 100 years should teach us a powerful lesson

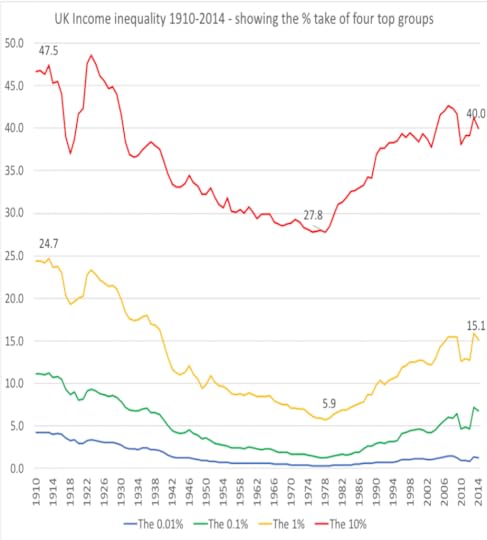

Over the NHS fundraiser’s lifetime, inequality has dropped but shot back up again. After this crisis we must keep it down.

‘By the time Tom was 57 years old in 1977, the best-off took less than 6% of all income in Britain; three times less than when he was aged 12.’ A birthday message at Piccadilly Circus. Photograph: Toby Melville/Reuters

[Article (by Danny Dorling) originally published on April 30th 2020]

Tom Moore entered the world on 30 April 1920 as Britain was emerging from the worst pandemic since mortality records began: the influenza of 1918-19. Total mortality in the UK rose by 24% in a year in 1918. Tom was just nine years old when the bitterly cold winter of 1929 increased mortality by 15%, and a newly married husband aged 48 when the influenza pandemic of 1968 led to a mortality increase of 6%.

We do not yet know how Covid-19, the pandemic that inspired Captain Tom to begin his record-breaking walk at the age of 99, will rank in this deadly league table; yet it will almost certainly be less deadly than the events of 1918, 1929 or 1968.

In 1937, when Tom was 17 years old, there was no National Health Service. It was a time of mass unemployment and mass poverty. One shilling in every six earned in Britain went to the best-off 1% of the population. The vast majority of Britons were poor. If they fell ill, they had to pay to see a doctor, or hope for charity.

When 20-year-old Tom was conscripted to the war effort in 1940, Britain began to change faster than it ever had before; the next 17 years would be some of the most remarkable in UK history. In 1957, when Tom was 37, the best-off 1% in the UK took only 9% of all national income. A great transformation had taken place and people were told they had never had it so good. But it would get better.

The influenza of 1968 returned in 1970 and again in 1972. One million people died worldwide. Yet it was a time when the global population was younger because of lower life expectancy than today; and it was a time of growing optimism and equality. By the time Tom was 57 years old in 1977, the best-off took less than 6% of all income in Britain; three times less than when he was aged 12. It was the smallest share they have ever taken; housing was affordable and there was full employment.

Tom could have expected the situation to get better still. But a very different UK emerged instead. Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979 heralded 18 years of radical Conservative economic policy. In 1997, when he was 77, the take of Britain’s 1% had doubled to 12% of all national income. When Tom turned 87, after a decade of “New” Labour, the share of the best-off 1% had risen to over 15%, which meant that inequality had returned to the levels they were when Tom was a very young man. Today the very best-off 1% in Britain receive around 14%, or a seventh of all income.

At the start of this century our leading politicians believed that the rich should be rewarded and the poor should be bullied. Though not very long from now, we may look back and see that it took the Covid-19 pandemic to bring to a halt the rise in economic inequality.

Though prime minister Boris Johnson likes to talk of “levelling up”, the coronavirus pandemic has instead resulted in a levelling down. Many Britons with no wealth will fall further into debt this year. Yet it’s estimated that a third of FTSE-100 companies have cut their chief executive’s pay as a result of the economic shutdown; anyone whose wealth is held in stocks and shares has seen it collapse in recent months; and house prices are falling, and are likely to fall the most where they were highest.

Captain Tom’s fundraising achievement, for which he has been promoted to colonel, is a tribute to Britain’s belief that our NHS is worth preserving. But charity efforts even of this magnitude can raise only a tiny fraction of the billion a week needed if the UK it is to fund its health services to the levels of Germany. Of all large European countries, it is Germany that has dealt with the pandemic the best.

At first, the economic impact of Covid-19 looks devastating. But think back to the first half-century of Tom’s life. Think of how his situation changed from one in which living in poverty was very likely, through to a time when his children could expect to have well-paid jobs, enjoy full employment and start a family in their 20s if they wished.

The last time economic inequality began to fall in the UK was around the time Tom was born, at some point between 1913 and just after the end of the first world war. The war debts could only be repaid by taxing the rich; no one else had enough money. The same is likely to happen again today, with the debts of lockdown and global recession.

Coincidentally, a century after Captain Tom was born, the prime minister announced the birth of his own son. But there is no need for Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds’ baby to live through such a rollercoaster century. We should learn from the past 100 years: pull inequality down, but this time keep it down.

For the original article and a PDF click here.

The falls and then rise of income inequality in the UK

April 29, 2020

How quickly might we forget the lessons of Covid-19?

My father still remembers the H3N2 influenza pandemic of 1968 when over a million people died worldwide. He remembers being too ill to get out of bed to tend to me, then an infant; but within a decade of that event it had been largely forgotten by most people. His father was a teenager during the 1918 H1N1 Influenza pandemic and thus at risk; but it had so little effect on my grandfather’s life that he never talked of it. Will Covid-19 be different?

The number of people who are dying today is small as compared to the 1968 pandemic, which was itself much smaller than that of 1918. However, thanks to improved public services and living standards a far higher proportion of the population are elderly today. We also tend to face much lower general risks. And so a pandemic today can become all consuming. It also more clearly reveals our deficiencies than pandemics did in the past.

In January 2020 the UK had five times fewer ventilators per person at risk than did Germany. The UK had been spending roughly a billion Euros less a week on its health services as compared to Germany. It was also possible that the UK had far fewer very frail people at risk, because so many more have died in recent years from austerity. When this is all over we in the UK should compare ourselves to Germany and ask why we could not plan as they did?

So what did we do? After weeks of inaction, on Wednesday March 11 ‘… some of the experts on the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies began to realise that the coronavirus was spreading through the UK too fast for the NHS to cope’. Others did not realize it was so serious at that time and it took a few more days to convince them. For example, on March 22nd the Times Newspaper reported the chief advisor to the Prime Minster, Dominic Cummings as stating “…if that means some pensioners die, too bad.”

On Thursday March 12th as the Financial Times has explained, the Prime Minster told the ‘…British public to prepare to “lose loved ones before their time” [but] said he would not follow the example of Ireland and Italy and close schools and ban sporting events to limit the spread of the disease.’ On March 21st a journalist in the Daily Mail, upon seeing all the evidence laid out before, said: ‘I see very little evidence of a pandemic’. He also wrote that ‘every human being in the United Kingdom suffers from a fatal condition – being alive.’ That journalist helped illustrate why much of the UK government and its advisers and people of his political persuasion do not understand collective risk and what matters most in life. This we must not forget. Such people will be around saying much the same things next time; but if we remember we can be better prepared for their views.

That same week a fund manager wrote ‘…Coronavirus has a mortality rate of less than 5%, so it isn’t going to be the end of the world.’ True, but who would image a few million less than 300 million dead as ‘not the end of the world’? A few days earlier, a market analysis had complained that panic had been caused by politicians because ‘…news which is likely to foment volatility is better delivered after market hours.’ Yes, someone did really say that! And then he went on to suggest: ‘There is indeed a virus among us, one far more damaging than that which goes by the name COVID-19.’ By this he meant people with different political views to himself!

It is very possible that too many people who held extremely individualistic attitudes, and valued older lives very lowly in the UK and USA held positions of influence in 2020. Time will tell, but if this is one lesson that we learn it is a lesson we ned to remember well.

On April 4th, as the situation began to settle, an esteemed Professor of Statistics suggested that: ‘if COVID deaths can be kept in the order of say 20,000 by stringent suppression measures, as is now being suggested, there may end up being a minimal impact on overall mortality for 2020 (although background mortality could increase due to pressures on the health services and the side-effects of isolation).’ It is worth comparing that number to the 55 times higher estimate of the 1,110,332 dead if we “did nothing” scenario that had been published just a few weeks earlier. We should try very hard to remember how we were flying blind when all this began.

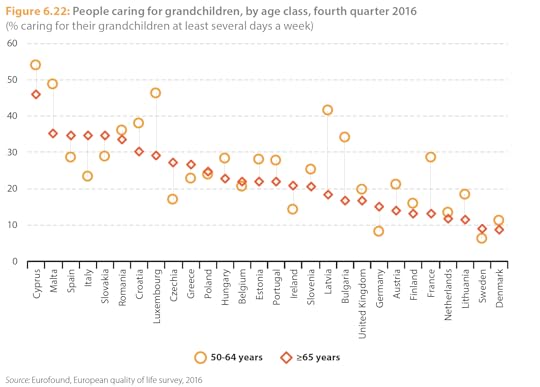

So what are we beginning to learn. One lesson has been that the number of people who died in each country in Europe depended (to an extent) on the prior living arrangements in that country – most importantly the extent to which mean old and young tended to live together, which varies markedly across Europe. In March, for those tested as having the disease, the mortality rate report across Europe varied from 9% per infected person in Italy and 6% in Spain, to as low as 0.4% in Germany; and 0.3% in Norway. These are all now much lower as the numbers of people tested rise and as people showing fewer symptoms are tested.

So why do I worry about us forgetting the lessons? It is because we did so before, and because we forget that we forget. I’ll end with two graphs. The first I drew on March 28th 2020. It showed what appeared to be exponential rises in mortality in Europe, because at that time mortality was rising exponentially in Europe. Although note that the mortality rates were very low. We should remember that we were once this frightened.

Mortality rate of those dying with Covid-19 per 100,000 people as of March 28th 2020

The second graph shows the proportion of grandparents who tend to spend at least several days a week caring for their grandchildren in different countries in Europe. Often this was because they lived in the same household. If Covid-19 got a hold in a country, and that was a country in which grandparents often lived with grandchildren, then because the grandchildren were sent home from school infection rates could initially increase. By April 8th the highest numbers of deaths in Europe had been reported in Spain and Italy; with twice as many dying in Italy than France; and almost fifty times fewer dying in Denmark than France.

Grandparents caring for grandchildren for several days a week (% in 2016)

There are a lot of lessons to learn, but chief among them is not forgetting what this felt like at the time. We were, after all, expecting a pandemic – we had been for years. So why were we so badly prepared? And what did we think was so important that we could not act more sensibly, more quickly and with better hindsight. We cannot justify making so many mistakes again.

For a PDF of this post or to see the original article on line click here.

References:

[1] https://twitter.com/martinmckee/statu...

[2] http://www.dannydorling.org/books/bet...

[3] https://www.buzzfeed.com/alexwickham/...

[4] https://twitter.com/DocMelbourne/stat...

[5] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/co...

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/65094a9a-6...

[7] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/ar...

[8] https://www.propertychronicle.com/a-f...

[9] https://www.aier.org/article/the-anat...

[10] https://thecritic.co.uk/has-the-gover...

[11] https://medium.com/wintoncentre/how-m...

[12] https://www.researchgate.net/publicat...

[13] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statist...

[14] As updated on March 22nd: https://www.cebm.net/global-covid-19-...

[15] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documen...

For a PDF of this post or to see the original article on line click here.

April 28, 2020

Decarbonising economies is like denuclearising weaponry—essential for survival

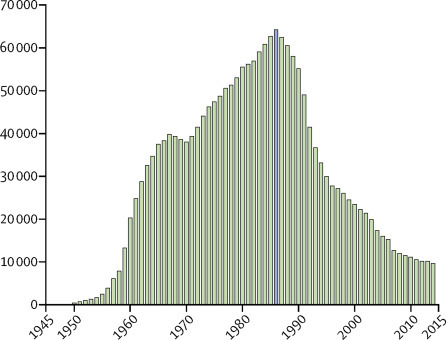

Humanity has been here before, facing what appeared to be an imminent end (figure). The rise in nuclear weapons was rapid, from the first two used on Aug 6 and Aug 9, 1945, through to 10,000 held by 1960, almost 40,000 in 1970, and peaking at over 60,000 in the mid-1980s. At the time, it did not feel like a peak; it felt as if we were all going to die.

FigureThe rise and fall in nuclear weapons held worldwide, 1945–2015

(Originally re-drawn here)

In the 1930s, a few people knew that nuclear weapons would be potentially cataclysmic. By the 1960s, there was a well-established anti-nuclear weapon peace movement, but the protestors were treated as fools by the media. By the 1980s, it was becoming clear that nuclear war was mass annihilation and could not be avoided by threats of mutually assured destruction. Disarmament began in earnest.

The climate emergency has a similar trajectory, but without that most imminent of threats. People’s reaction to both is similar: ignorance, acceptance, revulsion, and rejection, but only generation by generation. People tend to stick with what they believed as teenagers. Today’s teenagers know that the climate emergency is real, just as the teenagers who put flowers in the barrels of guns in the 1960s knew what their parents did not.

In the 1970s, hardly anyone knew that greenhouse gases would be potentially cataclysmic. By the 2000s, there was a well-established climate emergency movement, but the protestors were treated as fools by many. By 2019, it become clear that if left unabated, global heating would be disastrous and could not be avoided by the market foreseeing our assured destruction. Decarbonisation began in earnest, while millions marched to proclaim that this was not enough. Then, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic provided many people who have not experienced such turmoil before with an insight into what happens when normal life is up-ended.

No-one who is sane would choose or welcome in any way the shock of the 2020 pandemic emergency, but it has caused a much more rapid economic and consumption slowdown than would otherwise have ever been possible. The virus initially reduced CO2 emissions from China by a quarter, before they began to plummet worldwide, and the small number of human beings alive who can afford to fly internationally have been forced to dramatically reduce their international air flights. The pandemic has also illustrated how rapid and unified global action to protect health is possible when there is a political will.

A global demographic and economic slowdown had begun long before the virus hit. In a post-pandemic world, it would be unforgivable to simply return to business as usual. An acceleration of the slowdown that was already occurring before the pandemic began is humanity’s hope and should be our aim.

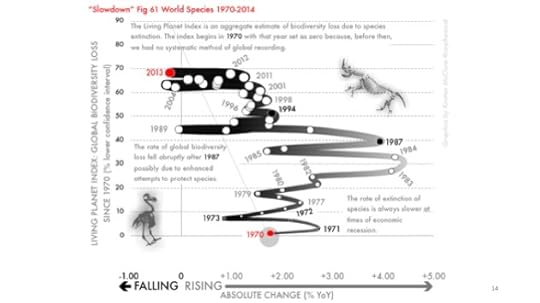

Shifting to a longer timescale, since life began on Earth, there have been five major mass extinction events. Six out of seven of all the planet’s species died 450 million years ago due to global cooling. Three-quarters were wiped out 370 million years ago, again due to climate change, and 250 million years ago, after another rapid climate change of 5°C warming, 24 of every 25 species became extinct. Some 200 million years ago, the climate changed again, and four of every five species on Earth were wiped out. The last of the great five mass extinctions occurred around 65 million years ago, when an asteroid that was 6–9 miles wide hit Earth, and three out of four of all species became extinct. Today, we are just a few decades into the sixth and most rapid of all mass extinctions. Humanity has had a worse and faster effect on the biodiversity of the planet than a huge asteroid.

The good news is that if you take extinction as the disappearance in sexual species of the very last breeding pair, then extinction is quite hard to achieve, although by no means impossible. The bad news is that this is not really the kind of extinction that matters for the wider environment. What matters most is the extinction of function: a species no longer having the numbers to fully play its part in the web of connections.

The planet can be saved—if we care enough to do so. Today, as Matthew Taylor and Jessica Murray observed, “…there is no way to completely shield young people from the reality of the climate crisis, and that would be counterproductive even if it were possible. Rather, parents should talk to their children about their concerns and help them feel empowered to take action”, just as a few of their parents and grandparents did before them to avert nuclear catastrophe. The emerging lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic give us an opportunity profoundly to re-evaluate our humanity, including a far more careful consideration of those yet to be born. Our future remains in our hands.

For a pdf of this article and a link to the original source, see here.

April 27, 2020

Three charts that show where the coronavirus death rate is heading

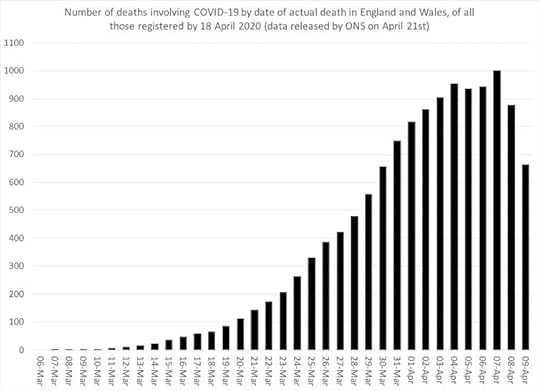

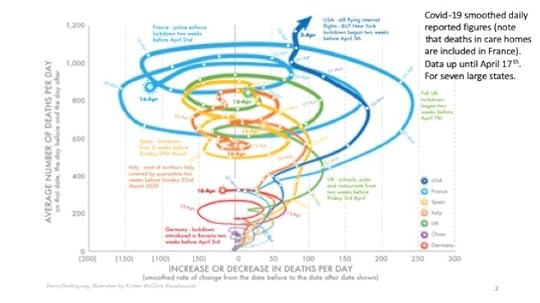

On April 7, The Conversation published three graphs showing the rise of deaths from COVID-19 in seven countries. This is an update 20 days later. What we could not have known then was that April 7 was the point at which the peak, or at least the first peak, in mortality in England and Wales was reached.

Analysis from the Financial Times, which includes deaths outside hospitals, has posited April 8 as the peak for COVID-19 deaths for the whole of the UK.

Here, those April 7 graphs are updated for Europe and geographical evidence is drawn together from around the rest of the world to try to paint a clearer picture of the direction in which we are heading – probably one where countries converge towards a single global death rate.

England and Wales reach a peak

First, the situation in England and Wales. The graph below shows the rise in mortality each day since the outbreak began, not just in hospitals, until April 9. The additional data is provided by the Office for National Statistics in its weekly reports.

This graph and the one below are based on smoothed data, which uses a moving average for the period from the day before to the day after each date shown to better illustrate a trend.

Mortality in England and Wales attributed to COVID-19, March 6 to April 9 2020.

Mortality in England and Wales attributed to COVID-19, March 6 to April 9 2020.Danny Dorling, Author provided

The peak by this method of counting occurred on April 7 when the smoothed number of deaths recorded was 1,001, compared to 944 on April 6 were 879 on April 8.

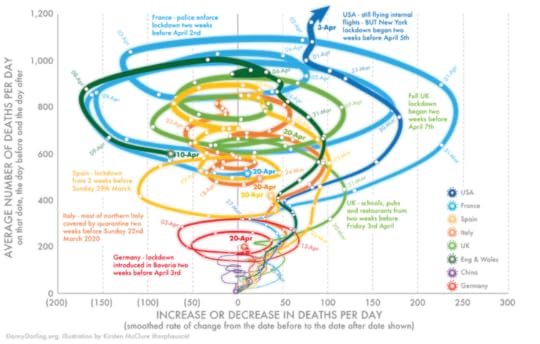

Rates of change in affected countries

The graph above is conventional. The one below is a bit different.

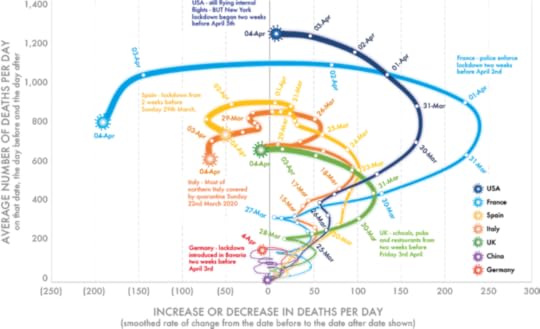

It shows both the smoothed number of deaths each day but now also the rate of change in that number. And it adds data from seven additional country datasets: France, the USA, Spain, Italy, China, Germany and the UK as a whole.

These seven countries are highlighted because they originally had the highest number of deaths. The data is more up to date in this graph because it is mostly drawn from the most recent daily hospital data.

Mortality in seven countries attributed to COVID-19 (January 23 to April 20, 2020)

Mortality in seven countries attributed to COVID-19 (January 23 to April 20, 2020)Danny Dorling, Author provided

The method of showing change used in the graph above was developed for my book, Slowdown, which I worked on with illustrator Kirsten McClure who turned my crude Excel graphs into the clearer visual shown above.

It’s a useful way to look at data when you are trying to demonstrate change over time. When a line curves to the right, deaths per day are increasing. When it curves to the left, they are decreasing. Loops indicate a change in trend – so death rates rising, falling and rising again.

This graph shows the rise in mortality in seven countries up until April 20. By this point, the daily number of deaths was falling most days in most countries, although it had risen to be very high in the USA.

Most intriguing is that from April 7 to 10, the shape of the curve for England and Wales, when all absolutely certain COVID-19 related deaths including in care homes are included, almost exactly matches that for France. This is significant because there is so much debate about how different European countries are doing, when in fact it is the similarities that are most remarkable.

In all the countries shown here, the fall in deaths may have begun a little earlier than the imposition of lockdowns would have suggested, although the lockdowns almost certainly accelerated the falls.

The looping effect was seen originally in China, and may suggest one outbreak superimposed upon another.

The rest of the world

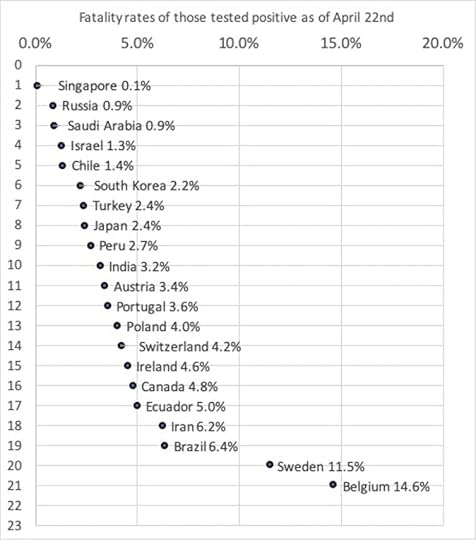

The final graph shows the current fatality rates of all those known to have the virus in the 21 countries that had conducted 10,000 tests by April 22, excluding the seven above.

Mortality in 21 countries attributed to COVID-19 of those testing positive for the disease by April 22, 2020.

Mortality in 21 countries attributed to COVID-19 of those testing positive for the disease by April 22, 2020.Danny Dorling, Author provided

It ranges from Singapore, where only one in 1,000 of all those who have tested positive have died, to Belgium, where 15% or almost one in seven have died. In Belgium, it is almost exclusively people who are very ill who are tested and so the mortality rate appears to be 150 times high than in Singapore where a much wider range of the public has been tested.

But the real mortality rate of these two countries will end up being very similar, and much nearer to the lower end of the range. It is extremely unlikely that Singapore, with its very efficient health system, is failing to record the deaths of those known to have the disease.

This illustrates a key point: over time, all of these mortality rates will probably begin to converge on a single global rate of those who have caught the disease. This is what has happened in the past. The flu of 1918 may have had a mortality rate as high as 2% of all those who caught it. In contrast, the H1N1 flu of 2009 had a mortality rate 100 times lower at 0.02%.

For COVID-19, the final rate will tend to be towards the lower end of the spectrum shown, if this disease is at all like previous pandemics, which we don’t know for sure yet.

The picture is complex. But these graphs tell us a few key things: England and Wales passed at least one peak on April 7. And, based on the second graph, it’s clear that rates have begun to cascade down in Europe. Across the globe, rates vary widely based on differing testing policies – but we can expect that they will converge around a single figure before too long.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For another link to the original post and a pdf of this article click here.

April 24, 2020

Stepping back to focus on the longer term (talking about slowdown)

Danny Dorling giving a short keynote at the British Sociological Association Annual Conference (on-line in a time of Covid19) on April 24th 2020.

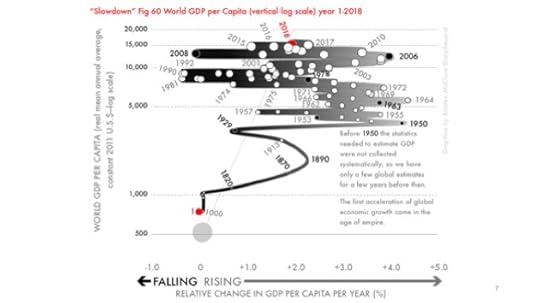

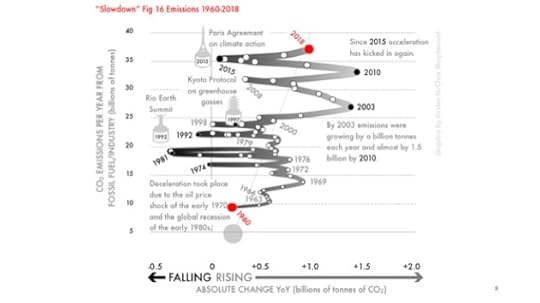

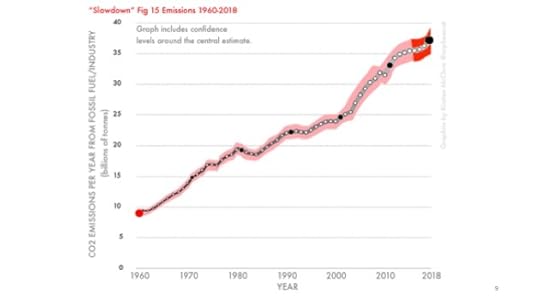

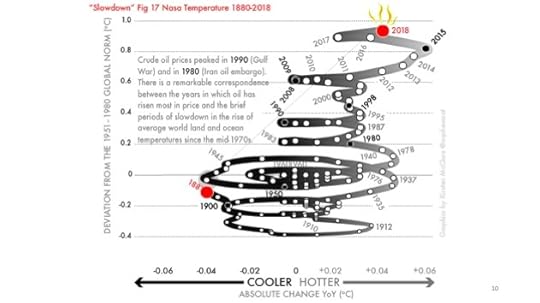

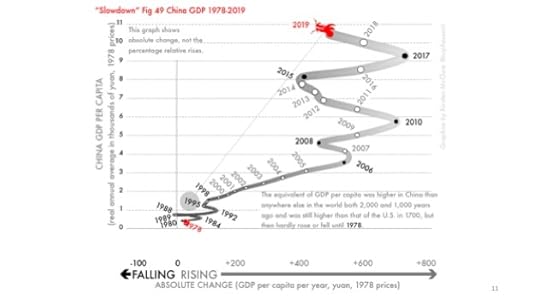

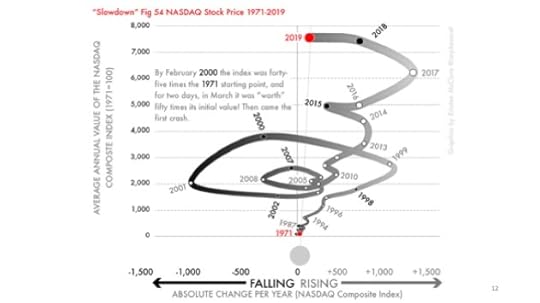

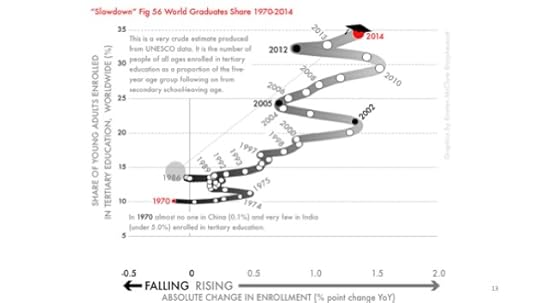

Click play below to hear the talk and just scroll down through the images below as you are listening. Each is one of the slides being referred to and all come from this book.

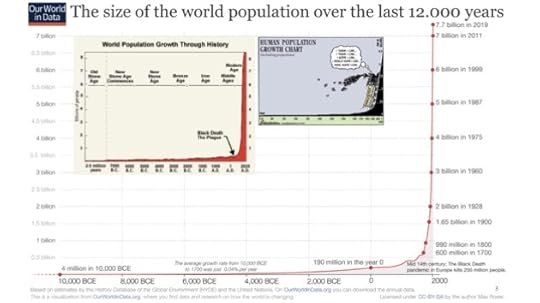

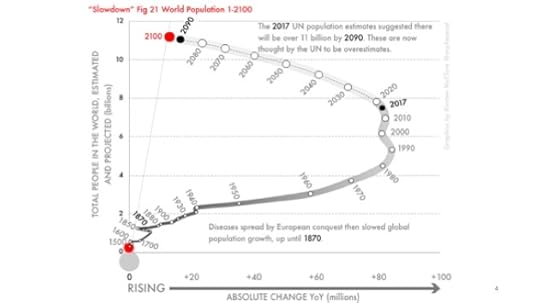

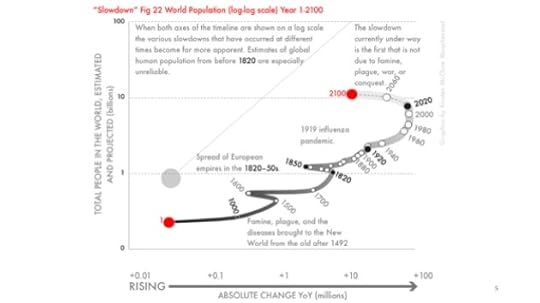

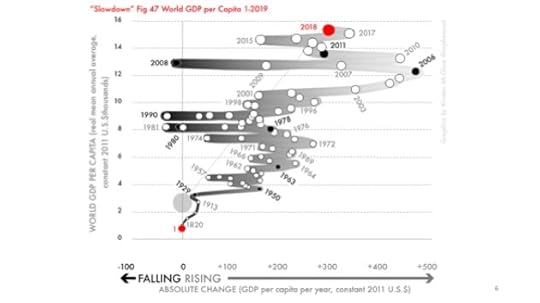

Slide 01

Slide 02

Slide 03

Slide 04

Slide 05

Slide 06

Slide 07

Slide 08

Slide 09

Slide 10

Slide 11

Slide 12

Slide 13

Slide 14

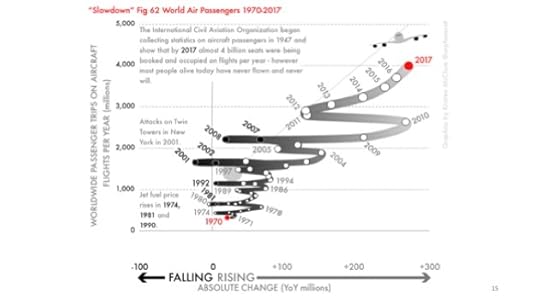

Slide 15

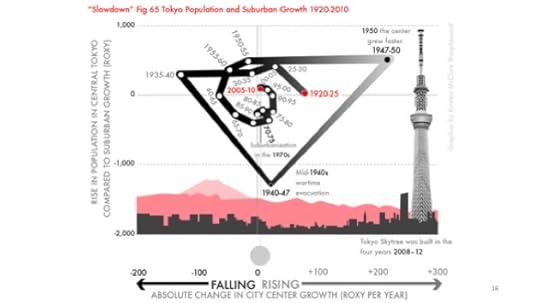

Slide 16

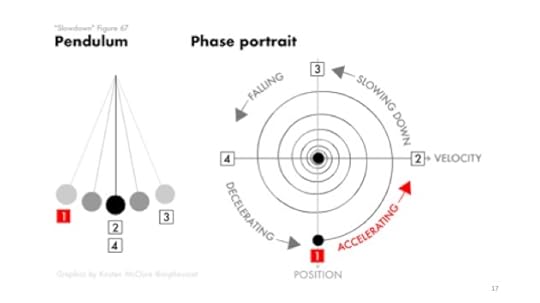

Slide 17

Slide 18

April 18, 2020

The Geography of Slowdown

Danny Dorling giving the final talk at the Geographical Association annual conference (on-line), on April 18th 2020

Fertility rates, growth in GDP per person, increases in life expectancy, and even the frequency of new social movements have all steadily declined over the last few generations – with the latest data from the most remote places now confirming that slowdown in upon us. Why not embrace the current slowdown as a moment of promise and a move towards stability?

The Slides for this talk can be found here: Download PDF (6.5 MB)

Download PDF (6.5 MB)

Concluding slide

April 7, 2020

Three graphs that show a global slowdown in COVID-19

Danny Dorling, University of Oxford

Almost as soon as the COVID-19 pandemic began, graphs and many other visualisations charting the rise of the virus started to multiply. Many show the cumulative number of deaths attributed to the virus. This number, of course, will always rise, but will also – eventually – plateau. A cumulative total can never fall.

Other published graphs have shown the number of deaths reported each day for various countries. These are more useful, but the reader is still left trying to discern the extent to which the rise from one day to the next is larger or smaller.

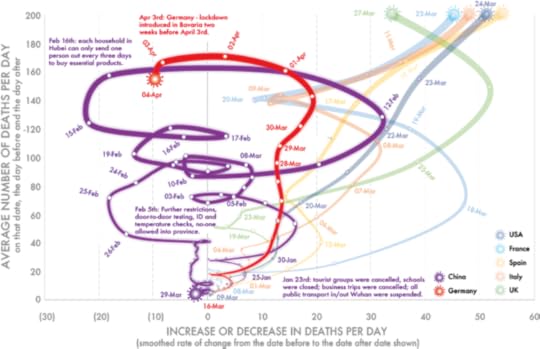

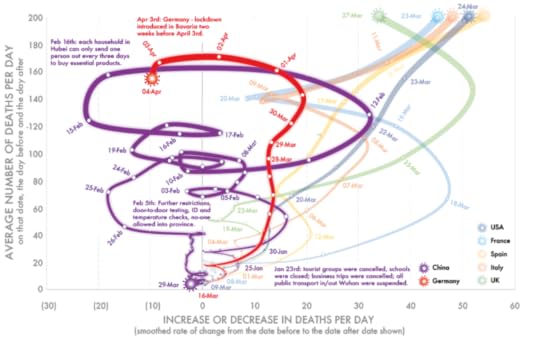

The graph below is different. It shows both the number of deaths each day and the rate of change in that number. Most importantly, it uses smoothed data – a moving average from the day before to the day after each date shown. This method of showing change is explored in my forthcoming book, Slowdown, which I worked on with illustrator Kirsten McClure who turned my crude Excel graphs into clearer visuals. It’s a useful way to look at data when it is change that is of the greatest interest.

The first graph (below) shows the rise in mortality in seven countries up until Thursday, April 2, 2020. At that point, the number of deaths was still rising every day in the US, France and the UK. The increases in mortality had begun to slow in Spain and Italy. Germany and China were reporting far lower numbers of deaths.

Mortality in seven countries attributed to COVID-19 (January 23 to April 2, 2020).

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

The picture began to change very markedly on Friday, April 3 and Saturday, April 4. As the graph below shows, the number of deaths in the US stayed the same (when smoothed). France was now reporting falling mortality, as was Spain and Italy. So too, for the first time, was the UK. The three-day smoothed daily number of deaths in Germany was also now falling. The graph is worth interpreting in the light of when the various national lockdowns began.

Mortality in seven countries attributed to COVID-19 (January 23 to April 4, 2020).

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

It is worth emphasising that both graphs above show a smoothed estimate of the number of deaths occurring on each day. This estimate is made by working out a three-day moving average of the number of deaths and it is shown on the vertical axis. The horizontal axis of the graph then shows the rate of change in that measure. Once a curve crosses to the left of the central axis, the number of deaths is falling. As I write, the number is not yet falling in the US, but it is about to.

When that graph was drawn just two days earlier, the picture it showed was less optimistic for France and the US, although even by April 2 it was evident that they too were swinging leftwards.

Reliability of the numbers

The numbers that are reported each day cannot be terribly reliable. For example, the daily tally of deaths are not those that have actually happened in the last 24-hour period, but rather the deaths that were reported in that period. In the early days of the pandemic, there were concerns about lower numbers being reported on Sundays as deaths then were not registered until Monday. Because of spending cuts, over the course of the past two decades in the UK there was an increase “in the median delay between occurrence and registration for deaths registered by a coroner from five days in 2001 to 18 days in 2018”.

In recent weeks, the registration of deaths has hopefully been faster than this; but additionally, the definition of what a death associated with COVID-19 is, has changed over the preceding weeks. The sources of data, however, tend to be very similar, including the data used here.

Because the numbers of deaths that have occurred in China and Germany are so much lower than in other countries, the graph below highlights this data. Mortality began to fall in China by February 14 and in Germany by April 2. However, wherever mortality falls it can rise again, as is shown by the various loops in China.

Mortality in China and Germany attributed to COVID-19 (January 23 to April 4, 2020)

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

Danny Dorling/Kirsten McClure, Author provided

While all the graphs above show that the rise in the number of deaths per day from COVID-19 may be abruptly slowing, they don’t confirm that this trend will continue. It has almost certainly been the social distancing measures put in place that have resulted in each of these seven trends altering as and when they did.

As modellers know all too well, the number of cases could conceivably rise again – and China appears to be the only country that has so far fully brought the novel coronavirus under control. On April 6, for the first time since January 2020, China reported no new COVID-19 deaths.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For the version on ‘The Conversation’, and a PDF of this article, click here.

Inset of Graph showing trends in seven countries up until April 4th 2020

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers