Danny Dorling's Blog, page 20

April 7, 2019

Danny Dorling: Peak Inequality – a discussion with David Runciman

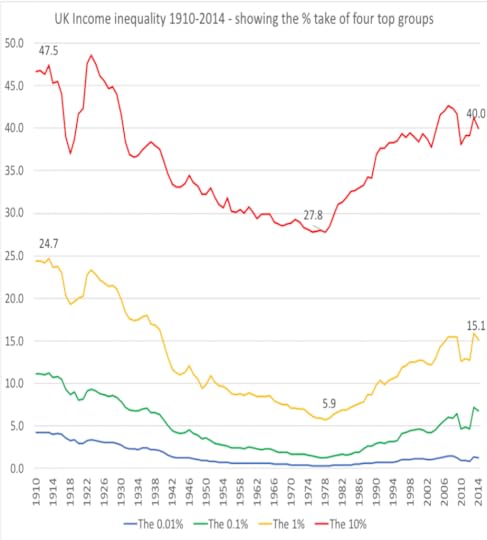

Inequality is the key political issue of our time. The dramatic rise of income inequality in the UK, from the mid 1970s through to today’s peak, created a state that was so unstable that Brexit was attempted.

Danny Dorling wrote his seminal work Injustice: Why social inequality persists in 2010, and was an early proponent of the urgent need for rapidly reducing economic inequalities before the implications of trying to live with such terrible divisions lead to a disaster. The subtitle of the book Peak Inequality was “Britain’s ticking time bomb“. He is now much sought-after as one of the foremost contributors to the debates surrounding it. teh graph below was taken form the book and appeared in the New Statesman.

The falls and then rise of income inequality in the UK

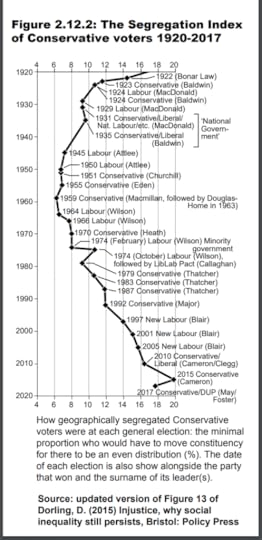

In Peak Inequality Danny Dorling brings together brand new material alongside a carefully curated selection of his most recent writing on inequality from publications as wide ranging as the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, New Statesman, Financial Times and the China People’s Daily. The book covers key inequality issues including politics, housing, education and health. He paints many pictures, and draws many graphs, maps and cartograms to illustrates just how socially, politically and economically divided the UK has become:

The political height of polarisation: The UK General Election Map of 2015

Danny explores whether we reached ‘peak inequality’ in 2018. He concludes by predicting what the future holds for Britain, as attempts are made to defuse the ticking time bomb while we simultaneously try to negotiate Brexit and react to the wider international situation of a world of people demanding to become more equal.

The fall, rise and fall again of Tory political segregation

In most affluent countries of the world equality is now on the rise. The UK still has to find its way. It is currently the most economically unequal state in the EU28 by the OECD measure of income inequality. To listen to a discussion about the book, click the arrow below:

Recorded at the Cambridge Literary Festival, The Divinity School, University of Cambridge, April 5th 2019.

Peak Inequality: Britain’s ticking time bomb

March 31, 2019

Rule Britannia at twelve days until Brexit – Why did it get this far?

The deadline is now Friday 11pm April 12th 2019. A 30 minutes talk by Danny Dorling in the free Blackwells Marque, Oxford Literary Festival, The Bodleian Quad, Oxford, March 31st 2019.

Join Danny Dorling as he explores his book ‘Rule Britannia‘ co-authored with Sally Tomlinson, which argues that the vote to leave the EU was the last gasp of the old empire working its way out of the British psyche.

Fuelled by a misplaced nostalgia, the result was driven by a lack of knowledge of Britain’s imperial history, by a profound anxiety about Britain’s status today, and by a deeply unrealistic vision of our future.

In this wide-ranging and thoughtful analysis, ‘Rule Britannia’ argues that if Britain can reconcile itself to a new beginning, there is the chance to carve out a new identity.

‘Rule Britannia‘ is a call to leave behind the jingoistic ignorance of the past and build a fairer Britain, eradicating the inequality that blights our society and embracing our true strengths.

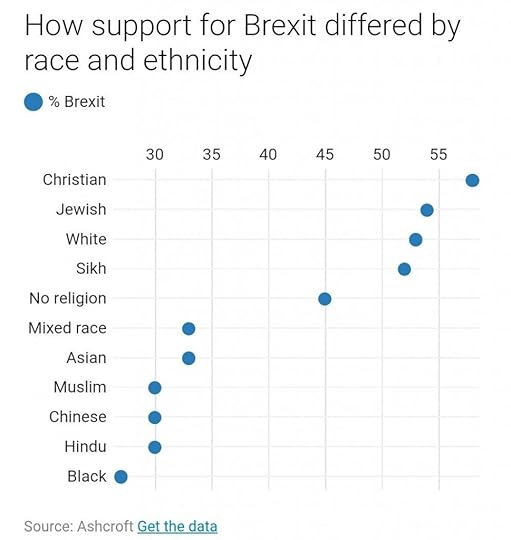

The image below was drawn (by others) using Lord Ashcroft’s Exit Poll data. Note that the sample size for Sikhs was only around 20 people and so is unreliable.It was, of course, the ‘white middle class’, especially the older members of that class who more often voted Conservative or UKIP, that group provided the great bulk of Leave votes in 2016, especially those living in the South of England – but why did they?

Support by Brexit on June 23rd 2016 by ethnicity and religion (Lord Ashcroft exit poll).

March 30, 2019

Communication by numbers, symbolic power and slowdown

A seminar for the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity, London School of Economics, March 29th 2019.

Audio recording of a seminar given on the subject of how to tell compelling stories about inequality, and social change using data. Danny talks about how to draw on statistics to present engaging and clear arguments and information to the media, the general public, policymakers and politicians with the aim of increasing awareness of inequality and helping to effect change. He shares some stories from his own experience of what works and what doesn’t, and why – and especially on why you really need to have your facts straight.

Fellows were asked to read this paper before coming to the seminar. The seminar concentrated on the complex issues of showing how change occurs, and an audio recording of it is below:

Are we now slowing down?

March 27, 2019

Still two weeks to go until Brexit?

On the eve of the House of Commons trying to break the Brexit deadlock, a public lecture concerning what Brexit tells us about the British.

On the night when the government began to post the following email to millions of UK voters, after 5.8 million had petitioned it in a matter of a few days. More than six million by the Wednesday:

UK Government response to 5.8+ million people signing a petition to revoke, just before it agreed to a debate on the issue of whether article 50 should now be revoked.

And the day before Donald Tusk said to the European Parliament: “You should be open to a long extension, if the UK wishes to rethink its strategy. 6 million people signed the petition, 1 million marched. They may not feel sufficiently represented by UK Parliament but they must feel represented by you. Because they are Europeans”

A public lecture by Danny Dorling speaking at the Ropetackle Arts Centre, Shoreham by Sea, March 26th 2019: On Brexit, British Empire nostalgia, economic inequality, political incompetence, and hope:

March 24, 2019

What has Brexit taught us about the British? The story so far.

Whatever kind of Brexit occurs – hard, soft, or even a last minute cancellation and staying in the European Union – the public and especially today’s university and school students (who had no vote) are going to be asking questions about why this has happened and what it means for many years to come.

The arguing and making of claims and counter-claims about Britain’s geographical status that has recently been taking place within the UK will probably not improve the image of Britain in the eyes of much of the rest of the world’s people. But there is an upside. The British may well learn a great deal about themselves as a result of having voted to ‘Leave’. Not least that Britain, and even Brexit, has its roots in the British Empire.

Traditionally British Geography, a subject that was partly born in this country due to Empire, has not been very good at explaining what the Empire was and why it mattered so much to Britain. Brexit may well be the point at which the English, in particular, finally learn about the importance of geography.

Geography is central to Brexit, from the Irish border, through to the modern day priorities of India. This talk includes the suggestion that living with the highest rate of income inequality in Europe was our real problem, not being in the EU. But why did we come to be so unequal and what does that half to do with the legacy of the British Empire? The source of our woes was not immigrants or some perceived lack of sovereignty, but of our own making.

Click play below to hear Danny Dorling speaking to the Geographical Association, meeting at Talbot Health School, Bournemouth, on March 20th 2019 – on the evening that Theresa May chose to try to condemn MPs in a public address to the four nations at 815pm, before she later (in effect) apologised for her actions.

For a full account of the argument made in this talk click here.

A portrait of Theresa May by Erika, February 2019

March 23, 2019

Comment by Danny Dorling on “Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline”

A provocative vision of the future in which the global population plummets, dramatically reshaping the social, political and economic landscape.

While depopulation may provide many benefits, such as higher wages for workers, improving the environment and more autonomy for women, there are (it is suggested) also disadvantages, such as worker shortages and ageing populations. This event will touched upon a wealth of research to illustrate the dramatic consequences of population decline, both good and bad, here are Danny’s brief comments:

The Keynote speaker was Darrell Bricker, Chief Executive of Ipsos Public Affairs & author of Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population

The Panelists were

Eric Kaufmann, Professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London & author of Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities

Danny Dorling, Geographer, University of Oxford

Robin Maynard, Director, Population Matters

Sarah Crofts, Head of Analysis for Ageing and Demography, Office for National Statistics

Kelly Beaver, Managing Director, Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute (chair)

The earlier book Danny was referring to, (Population 10 billion) which suggested a year 2100 population of 9 billion was more likely than 10 billion, can be found here:

And with Stuart Gietel-Basten his most recent book on demography is this one:

Why Demography Matters?

March 20, 2019

Austerity bites—falling life expectancy in the UK

On 8 March 2019 Lu Hiam and Martin McKee, referring to the most recent report from the Institute of Actuaries, said that we should not be surprised to discover that life expectancy in the UK has fallen by just over a year for both men and women since projections were made in 2015. They explain that the Department of Health and Social Care described the early warning of the start of the deterioration in life expectancy as “a triumph of personal bias over research.” The UK government and its agencies were not just failing to publish their internal monitoring of the situation; they were actively rubbishing the work of others. In such a political climate it is hardly surprising that the warning signs were ignored. The question this raises is why were competent, able, intelligent people at the heart of government choosing to ignore the statistics?

On 11 March 2019, Harriet Pike explained that the actuaries now saw the change as a “new trend rather than a blip.” She explained that three months earlier, Public Health England, had considered the reasons and decided to give less prominence to cuts in health and social care spending. Instead they ”concluded that slowing improvements in heart disease and stroke, high winter mortality from flu in several recent years, the growth of dementia as a recorded cause of death, and more deaths from drug misuse among younger people have all played a part.”

What Public Health England (and by association the Department of Health and Social Care) fail to consider is why the rate of improvement in heart disease had slowed; why more people suffering a stroke are now dying than would have died if the previous improvement in care had continued; why mortality was higher than usual in winter when the recent winters were all (without exception) unusually warm. Influenza as a substantial reason has been debunked. People who suffer dementia are now dying earlier than that group did before. This is almost certainly because care for people with dementia has worsened as austerity bites. People’s families are less able to care for them in these austerity years; and adult social services have been repeatedly decimated.

It is now too late for all those who have died. And it is probably too late for all those who will die early in 2019 and 2020. What we can now do is start to collate the evidence of why this huge mistake happened. On 12 February 2014, the deputy editor of the New Statesman, Helen Lewis, and I received an email from the Business Manager to the Chief Knowledge Officer of Public Health England.

It read:

Dear Professor Dorling and Ms Lewis

I am writing on behalf of Professor John Newton, chief knowledge officer at Public Health England. The attached article written for the New Statesman contains a number of factual inaccuracies Professor Newton is keen to rectify. Hopefully we can arrange a time for Professor Newton to speak to you shortly.

There were no factual inaccuracies in the piece. I responded by putting online a fully referenced version of the article to which the business manager was responding. That exchange took place over five years ago.

There will, at some point in the future, be a public inquiry into the events of 2014 to 2019, the years in which life expectancy fell in the UK. What matters now is to keep the evidence safe. If you are working in public health make a record of the emails you receive, the unpublished internal documents that are relevant. Keep it all. That future inquiry will be used to learn the lessons that need to be learnt so this never happens again.

For a PDF of this blog and the on-line BMJ version click here.

Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for Health, 2012-2018

March 18, 2019

Two weeks to go to Brexit?

There may be a silver lining. Brexit is a much larger national disaster than the 1956 Suez crisis, and more embarrassing.

But just as Suez was partly responsible for why we made so much social progress in Britain in the 1960s so, too, Brexit may galvanise the young to reject an old elite that made such bad decisions.

A public talk by Danny Dorling given on the Cornwall/Devon border on March 16th 2019. Both Cornwall and Devon, like most other counties in the South of England, were strong supporters of Brexit:

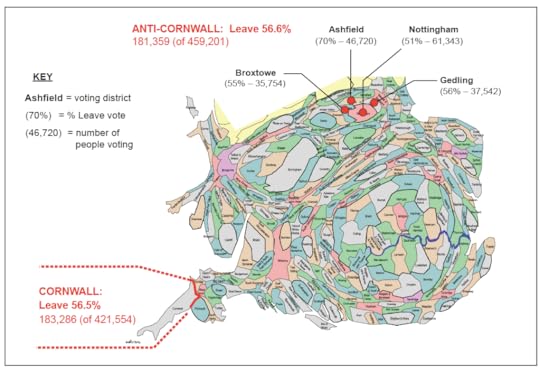

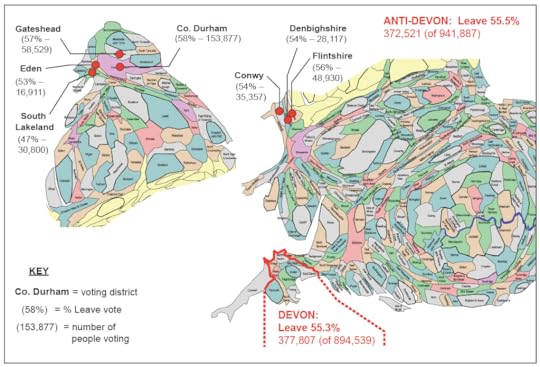

Although a fractionally higher proportion of people voted to Leave, out of all those who voted in the areas contrasted with Cornwall and Devon in the two maps below, in both cases a higher overall turnout in Cornwall and Devon meant that the two southern countries provided more Leave voters to the Leave total. This was despite their electorates being smaller than the comparator “anti” areas. This same exercise can be carried out for every single county in the South of England, always using different comparator areas of the rest of the UK, until every single area outside of the South of England has been included. It was a majority Southern English vote out. The large majority of older people in the UK live in the South of England. [Note: “of” below in brackets gives the total size of the electorate that the leave vote was a proportion of. The percentage are only of all those who voted, and hence ignore turnout]

Cornwall in the 2016 EU referendum and “anti-Cornwall”

Devon in the 2016 EU referendum and “anti-Devon”

For more details of these issues, see the 2019 book this talk was based on: Rule Britannia

March 13, 2019

Mid-March 2019: What Brexit now told us about the British

What on earth will happen now? Will some people never learn about the British past, the nature of its empire, its decline, and how all this is linked to Brexit?

On March 11th 2019 Danny Dorling gave the annual Guernsey Oxford Lecture in St James Concert and Assembly Hall, College Street, Guernsey.

A recording is below.

The lecture begins with the background to the vote and with a discussion of what we still not fully understand:.

Following the referendum in 2016 there was much quick speculation about which groups in society contributed to the leave campaign’s win. Much early comment missed the true picture. But it is also more interesting to ask what factors led to the outcome of the referendum and what these tell us about the changing state of Britain over the last few decades.

How has British society changed; for example in relation to inequality, health outcomes, housing and educational opportunities; how do these changes compare with other countries? What do they tell us about the current state of Britain and how the British people could adapt to their future post Brexit, whatever that brings?

Click on the triangle below to listen.

[Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford and a fellow of St Peter’s College. He grew up in Oxford and after going to university in Newcastle upon Tyne he has held posts in various universities in the UK and overseas before taking up his current post in 2013.]

March 5, 2019

Oxford Housing and the Survivor Syndrome

You read this magazine [The Oxford Magazine] and because of that you almost certainly know how the start of the story goes, but please bear with me, the ending is different. I am assuming that you have lived in or near Oxford for some time. By near, I include London.

You are at a social function. It could be a gathering for new postgraduate students who have just rented their first room in a shared flat. It could be a college dinner and you are sitting next to the newly appointed associate professor. It could be a garden party, or a carol concert, or at drinks after a lecture, or a rather convivial event organised by a head of house, school, faculty or department. Old staff may well carry on working to their retirement, and a few wish to extend their tenure long beyond that; but as the turnover of new staff in this university is so high and you have been around for some time, you will know that the following scenario almost inevitably repeats itself again and again.

You make the mistake of asking how they are settling in. It is a better opening gambit than the predictable ‘so what do you do?’. They look a little wary, and then they tell you. They think they have made a mistake in their housing choice. The bus into Oxford takes well over an hour and they are spending three hours a day commuting; or the rent in Oxford is astronomical and the quality of place they are renting is atrocious; or they cannot get their offer on a home accepted despite it being in the catchment of one of ‘those bad’ schools and despite being told house prices are falling due to Brexit.

You give them the look, the Oxford look. It is the Oxford way, to give the Oxford look, and you have slipped into the way. You are on autopilot because you have been in this situation so many times before. Your brow furrows, you change your stance to appear to be listening intently, you look concerned, sympathetic, you ooze apparent empathy. You say, “where are you living now?”

Their story unfolds. They are hesitant at first, but they want to know if they have made a mistake. Their implicit question: “What is the secret to being well housed in or near Oxford?” They are new. They do not know.

It is all a little embarrassing. After all, if the young woman you are talking to is a DPhil student her problem would be far less of a problem if she had parents who could help her out. The university has been so generous in offering her a place to study, and she has been so fortunate to receive research council funding for her fees and a stipend to live on; the only problem is the rent and the fact she needs to eat as well as sleep.

It’s so much rent every month for such a squalid room. The evening bar job in the White Rabbit helps, but is tiring. She worries about the insecure contract with her landlord, about her friend who is illegally sub-letting the sofa and what should happen if that is discovered. She worries that the rent will rise. She is looking into house sitting for people who go away in the summer. You tell her that a mortgage on that property would only cost half as much as what she and her legal and illegal co-tenants are all collectively paying in rent. It does not cheer her up to know just how much money her landlord is making, enough from just this one letting to spend all his days on cruise holidays. It’s ‘the Oxford housing market’.

“What is the university doing?”, she asks you. “Well it built some blocks of flats at the south end of Port Meadow” you reply. “Some even have a little kitchen in them and an oven! But because there was so much uproar about how the flats spoilt the view, when the old paper mill site at Wolvercote was to be developed the university bottled it and sold to a private developer,” you tell them, knowingly, showing off your detailed knowledge of all things Oxford, while not actually being at all impressive.

You continue: “I would have built an Italianate mock village, looking a little like Portofino or Portmeirion”, you joke, “in front of those new blocks of flats. Imagine how much better the view south across Port Meadow from Wolvercote would have been then? They could have been built to be let to university key workers”, you suggest. The bursar, who used to work in the City of London, overhears you and inwardly sighs. ‘There you go again, displaying your complete ignorance of the way money markets work’ he thinks as he smiles pleasantly and wonders away towards a potential donor, glass (for them) in hand.

A week later the new Associate Professor tells you of his problem renting. Your brow furrows and you look concerned and shift you stance to appear to be interested. His partner is expecting a baby and no landlord will rent the couple an apartment in Jericho, or anywhere nearby where they want to live. Why rent to a family with a child and risk the inevitable extra wear and tear? But they have finally found somewhere to live on the eastern edge of the city, and it will work until the child is aged four. As you talk there is, as always, the potentially embarrassing issue that might be raised of money. He is American so the risk is higher. He has not yet been in Oxford long enough to know that you can talk about anything, sex, politics, whatever, as long as you don’t mention inherited wealth or where the children go to school.

“My college doesn’t help”, the new professor tells you, as if the city’s problem would be solved if only all the colleges helped all their associate professors to buy a house. That would be a little like going back to the days when the dons lived in college, you think to yourselves. Where if you left your job you also left your home. You quip about how Oxford initially expanded only when the dons could finally stop having to pretend that they were celibate. Only then could they build grand houses for themselves on the Woodstock and Banbury roads; town houses with a basement for the male servants and an attic for the females ones. The quip doesn’t help, but to quip is the Oxford way.

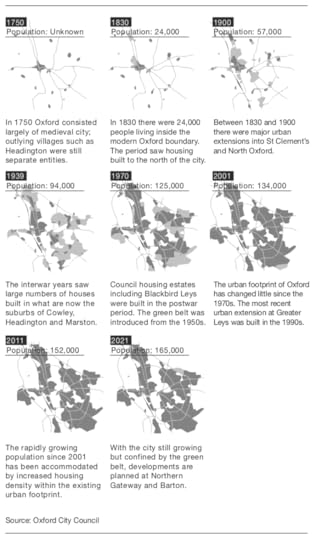

An older member of staff tells you of a problem with their children’s primary school. The staff keep on changing every year, often during the school year, and “they are all so young and inexperienced”, she says. “The last head teacher they appointed was incompetent and has already resigned. It is as if they can’t find someone who wants to do that job for any length of time who can also live in or around Oxford.” You tell them you once saw a series of maps of how Oxford expanded over time. The light grey areas on the map were what had been newly built. The maps showed that the city abruptly stopped expanding after the 1970s. “The reason” you say, to show (in the Oxford Way), just how very clever you are, “was not because of the green belt, but because the car factory was no longer taking on any new staff”.

You warm to your theme. “Tens of thousands of men used to work in the factory in Cowley. Almost all were married and had children. When their jobs were not replaced it was mostly people from the hospitals and universities that took over living in their homes. Just a few thousand people work in the factory today. Oxford did carry on expanding outwards in the 1970s, 80s and 90s; but into other peoples’ neighbourhoods and communities, not onto green fields. That is why we have such a crisis now, much worse than before”.

It doesn’t help to explain. They know that your children don’t go to a school like their children’s school. They know that somehow you managed to navigate the Oxford way. They don’t know how. You change the conversation.

Is there another way? The university has plans, but they mostly involve bringing in more students and staff to the city, a new graduate college and a new trunk road so that those without some financial advantage can commute in from further and further away each morning. The high turnover of young academics makes the snapshot at any one time look particularly impressive. So many amazing CV’s to hand at any one instance in time for the smiling snapshot picture that is the Research Excellence Framework, like baubles on a Christmas tree. Those who have made it are not unduly concerned. The most pressing perennial issue in the Oxford Magazine is why invitations to the grandest of summer garden parties were not given out this year to some of the retired academics who still live in the city.

Two local people died homeless in Oxford in late January 2019. As children they had both been pupils at Cheney school, then the average school in the city. Most of the homeless people who have died recently in Oxford grew up in the city or nearby.

The government has plans. A million new homes in the countryside between Oxford and Cambridge, along the route of the first quarter segment of the new M25+. Initially they will just label it an ‘expressway’ to imply it will not be gridlocked. It will feed into the M40, and on to London. And, if ever built, it will be gridlocked as it approaches Oxford. Their plans will not solve the housing problem.

In great contrast, her majesty’s opposition have plans, including a commitment to the compulsory purchase by the state of agricultural land on the edge of those cities in which there is the greatest housing need, and no support for the new expressway, just for a better rail link. The rail link would not be gridlocked; and much of the new housing would be allocated on the basis of need, not to make profit for greed.

The governing bodies of colleges with land around the edge of Oxford prick up their ears. Someone had told them that the Oxford way means it is their duty to do whatever they could to maximise the growth of the college endowment. To do less would be a dereliction of their duty as a trustee of an educational charity. Education is, apparently, all about amassing enormous wealth.

Key members of the governing body hold confidential talks with property developers who wanted to build detached homes on the edge of Oxford, large houses with double garages for the most affluent of London commuters. These will be “homes for your children” the oily executive from the property company lied at the public meeting held in Old Marston back in 2018, as he looked the scruffy man who had asked the question directly in the eye. He assumed the man knew little about housing. That man was me.

The bottleneck will be broken. It was broken before, between 1930s and the 1960s. The homeless have been well housed before, many decades ago. The university and its colleges have never played a progressive role in this story, that may just be their way. It is a very long and old story. One day, when I am a very old man, I may still be here. I don’t want to end my days clogging up a family house in New Marston for years after my children have finally left home. If I fail to escape this city in retirement I would like to end my days in an apartment with a lift and no stairs that had been carefully built into one of the hill sides overlooking the city. I don’t need much space, moving recently to Oxford has taught me how few material possessions you really need to retain. But you would be amazed just how many apartments could be built into those hillsides, especially if very little space were reserved to park cars.

I would hope that a new family were living in the house I now live in, and that they could then walk to work or school. A family of five last lived in it in the 1930s. I would hope that all around me were cycle lanes, students, primary school teachers, head teachers, and associate professors. And I would hope that the biggest worry I had would be whether the invitation to the summer garden party would arrive each year, so that I could set off in my gown in my electric buggy down into the city where the university now funded itself on the back of the tourist trade, rather than relying on arms dealers or plutocrats attempting to white wash their reputations. In my ageing regalia, I would continue to play my part in the entertainment.

I imagine a conversation with a newcomer and confide in them, annoyingly, “in my day you know, it was almost impossible to afford to live in this city, the roads were choked with cars and the colleges were choked with the lingering scent of bigotry. There were people sleeping on the streets, locals were considered to be miscreants, and the tourists were resented”. And they will listen politely, without a care in the world over the truly affordable rent they pay for the home on the hillside that they too have right to live in for as long as they wish, regardless of who they work for, or if they work.

Click here for a PDF of this article and for where and when it first appeared on-line.

The growth of urban Oxford, 1750 to 2021

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers