Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 8

May 23, 2016

George Egerton: Writing a ‘Topsy-Turvey’ World

I’m delighted that my feature ‘George Egerton: “Writing a Topsy-Turvey World”‘ was long-listed for the prestigious THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition. You can read my profile of the life and writing of this extraordinary woman on the Thresholds website here, or below:

George Egerton

George Egerton: Writing a ‘Topsy-Turvey’ World

by Eleanor Fitzsimons

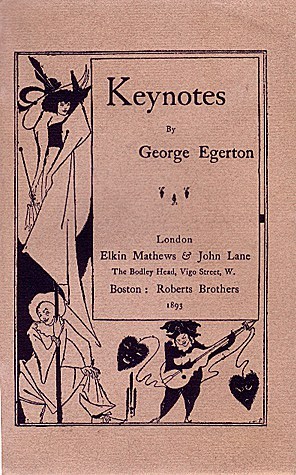

Surely, a proto-modernist writer whose experimental approach and provocative themes were echoed, decades later, in classic works by James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence should enjoy an enduring reputation. No one would countenance the neglect of an author whose challenging first collection of short stories, Keynotes, sold more than six thousand copies in its first year, was translated into seven languages, and influenced Hardy’s Jude the Obscure. Yet the name George Egerton is rarely mentioned outside academic circles.

Perhaps Egerton, a woman, ensured her own neglect by engaging in unflinching criticism of the patriarchy. In ‘Now Spring Has Come’, the second story in Keynotes, she insisted that woman should embrace her true and turbulent nature, when she wrote: ‘the untrue feminine is of man’s making.’ Egerton’s sensual exploration of such dangerous themes provoked a backlash so intense that Punch magazine reflected the unease she incited among its Victorian readers by parodying her viciously in ‘She-Notes’ by ‘Borgia Smudgiton’.

Best remembered – if remembered at all – for Keynotes, Egerton was born Mary Chavelita Dunne in Melbourne, Australia, in 1859, to Isabel George, a Welsh Protestant, and Captain John J. Dunne, an Irish Catholic. A militiaman’s daughter, Egerton’s unsettled childhood unfolded between Australia, Chile and New Zealand, where her father participated in the brutal suppression of that country’s indigenous Maori people. She was also educated for a time in a German Catholic boarding school. The early death of her mother, when Egerton was just fourteen, obliged her to abandon aspirations of becoming an artist in order to spend her formative years in and around Dublin, helping her widowed father to raise her younger siblings. As a result, she considered herself ‘intensely Irish’. Several of her stories tackle Irish themes: ‘The Marriage of Mary Ascension’ explores clerical and parental oppression in middle-class Ireland, while ‘Mammy’ includes an account of prostitution in Dublin.

Once her father could spare her, Egerton trained as a nurse and lived in New York for a time, before returning to Ireland as travelling companion to the Hon. Charlotte Whyte-Melville. When Captain Dunne discovered that Whyte-Melville’s husband, Henry Higginson, an Episcopalian priest, was having an affair with his daughter, he threatened Higginson at gunpoint, prompting Egerton to flee to Norway with her lover. Their marriage, contracted in June 1888, endured for less than a year and, shortly afterwards, Higginson, a volatile alcoholic, died of complications related to his illness. Although Egerton lived in Norway only briefly (she soon moved on to London), her time there honed her literary abilities. A talented linguist, she had learned Norwegian and immersed herself in the works of Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg and Nobel Prize-winner Knut Hamsun, with whom she enjoyed a brief romance and whose work she translated into English. She used her relationship with Hamsun as the inspiration for ‘Now Spring Has Come’. Egerton also studied the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche a decade before they were translated into English; she references him in several of her stories.

In November 1891, Egerton married Egerton Tertius Clairmonte, a Canadian citizen and struggling novelist whose lack of success obliged her to take up her own pen in order to supplement the family income. It helped that the couple had moved to rural Ireland where Egerton encountered few distractions. Her pseudonym paid tribute to her late mother, whose maiden name she took, and also to her husband. Remarking that this was ‘the only provision that he ever made for her’, Egerton’s biographer, Terence de Vere White, noted: ‘Her elopement with Higginson gave her the material for a book; her second husband, by his dependence on her, gave her the motive to employ it.’ George, the couple’s only child, was born in 1895, the same year his parents divorced. By then, John Lane and Elkin Mathews of the Bodley Head had published Keynotes (1893), which Egerton dedicated to Knut Hamsun, her former lover.

In November 1891, Egerton married Egerton Tertius Clairmonte, a Canadian citizen and struggling novelist whose lack of success obliged her to take up her own pen in order to supplement the family income. It helped that the couple had moved to rural Ireland where Egerton encountered few distractions. Her pseudonym paid tribute to her late mother, whose maiden name she took, and also to her husband. Remarking that this was ‘the only provision that he ever made for her’, Egerton’s biographer, Terence de Vere White, noted: ‘Her elopement with Higginson gave her the material for a book; her second husband, by his dependence on her, gave her the motive to employ it.’ George, the couple’s only child, was born in 1895, the same year his parents divorced. By then, John Lane and Elkin Mathews of the Bodley Head had published Keynotes (1893), which Egerton dedicated to Knut Hamsun, her former lover.

In a series of interlinked stories, Egerton’s first collection explores the gradual acceptance by her female protagonists that the purity required of them was a patriarchal construct imposed in order to deny them sexual freedom and fulfilment. In ‘Now Spring Has Come’, she was scathing in her criticism, writing:

Men manufactured an artificial morality; made sins of things that were as clean in themselves as the pairing of birds on the wing; crushed nature, robbed it of its beauty and meaning, and established a system that means war, and always war, because it is a struggle between instinctive truths and cultivated lies.

Egerton’s women reject their proscribed roles as guardians of morality, and refuse to engage in the heteronormative courtship plots familiar to readers of the time. Instead, they cooperate with other women, often overcoming constructed ethnic and social divisions in pursuit of agency and self-determination. ‘Woman, where her own feelings are not concerned, will always make common cause with women against men’, she wrote in ‘The Spell of the White Elf’, the third story in Keynotes.

While most of Egerton’s heroines are white middle– and upper-class women, in ‘Under Northern Sky’, Marie Larsen, a maidservant, entertains her drunken master with compelling tales in a bid to ensure that her mistress enjoys an uninterrupted night. In doing so, she ‘[takes] the enemy by stratagem’. The emancipated women that populate these dangerous and destabilising stories prompted comparison to Ibsen and sparked intense speculation as to the true identity of their author. Reviewing Egerton’s collection for The Academy in 1894, literary critic William Sharp described her fictional world, where women explore their desires and pursue supportive relationships with other women, as ‘topsy-turvey’.

Although closely associated with the fin-de-siècle New Woman movement, Egerton was uncomfortable with her inclusion: ‘I am embarrassed at the outset by the term ‘New Woman’’, she admitted. In an interview with American periodical Book Buyer, she confessed to having no views on ‘emancipation’ or the ‘woman question’. Unlike true New Woman writers, Egerton adopted an essentialist approach to gender, encouraging women to abandon all ambitions of emulating men in order to focus on the realisation of their own potential. In her epistolary and largely autobiographical novel Rosa Amorosa, she wrote:

Broadly speaking, woman has given most of her energy to a development of masculine qualities, instead of a cultivation to the utmost of the best in herself – as woman – with the object of producing the finest type of womanhood.

Although her exploration of sexual emancipation and self-actualisation resonated with New Woman preoccupations, Egerton shunned notions of equality. Yet, while she envisaged an alternative calling for woman, her forthright language reflected the fury of the burgeoning women’s rights movement. In ‘Now Spring Has Come’, she wrote:

What half creatures we are, we women! – hermaphrodite by force of circumstances, deformed results of a fight of centuries between physical suppression and natural impulses to fulfil our destiny.

Egerton loathed the duplicity of Victorian society, which she summed up in a sardonic letter to her father, writing: ‘sin as you please but don’t be found out it’s all right so long as you don’t shock us by letting us know.’ Little wonder her protagonist in ‘A Cross Line’, the first story in Keynotes, dreams of escape:

A great longing fills her soul to sail off somewhere too – away from the daily need of dinner-getting and the recurring Monday with its washing, life with its tame duties and virtuous monotony.

Although Egerton intended ‘A Cross Line’ to be the last story in her collection, the Bodley Head insisted it go first since, as Professor Margaret Stetz argued:

With its plot based on casual adultery, its references to unwed mothers, and its flattering portrayal of a woman who drinks whiskey, goes fishing alone, and smokes cigarettes, ‘A Cross Line’ […] guaranteed attention for the whole book.

Fearless in her choice of theme, Egerton also subverted conventional genre boundaries that set long-form and short-form fiction apart. Norwegian academic Gerd Bjørhovde insists that readers were ‘as shocked by the way she wrote as by what she wrote’. Her stories spill into each other, chasing themes from first page to last, as she explores the innate wildness of a  woman’s nature and allows her female protagonists to seize opportunities for self-knowledge and control of their destiny. In Discords, her darker and far less successful second collection of stories, Egerton documents the barriers women collide against when attempting to break free from rigid Victorian norms. Here, she explores alcoholism, marital abuse, prostitution and suicide. In ‘Virgin Soil’, the fifth story in the collection, a newly married woman is destroyed by her ignorance of the sex act.

woman’s nature and allows her female protagonists to seize opportunities for self-knowledge and control of their destiny. In Discords, her darker and far less successful second collection of stories, Egerton documents the barriers women collide against when attempting to break free from rigid Victorian norms. Here, she explores alcoholism, marital abuse, prostitution and suicide. In ‘Virgin Soil’, the fifth story in the collection, a newly married woman is destroyed by her ignorance of the sex act.

Only in ‘The Regeneration of Two’, the last story in Discords, does Egerton sound a hopeful note, allowing her protagonist to enjoy a fulfilling, non-marital romance and a gratifying career helping other women. As American scholar Martha Vicinus suggests, this decision to lighten the tone may reflect Egerton’s ‘need to imagine a better world where women work together and men understand and keep their freedom too’. It is telling that she set this story in her beloved Norway rather than Victorian England, where she had made her home by then. While Egerton had plenty of detractors, she had supporters too. In 1895, publisher John Lane, with whom she had a romantic liaison, wrote to her from America, assuring her that her stories were ‘very much in the air’ there. Adopting the title ‘Keynotes’, he published a series of New Woman fiction under the Bodley Head imprint.

Egerton also wrote for quarterly literary periodical The Yellow Book: her story ‘The Lost Masterpiece’ was included in the very first issue in April 1894, and her connection with this publication created an association with the Decadent movement. By echoing Oscar Wilde’s style in several of her stories, and quoting him in an epigram to ‘A Little Gray Glove’, the fourth story in Keynotes, she reinforced Wilde’s association with New Women’s writing. Several passages in ‘A Cross Line’, which imagine a dance in a ‘dream of motion’, take much from Wilde’s Salome, although Egerton’s woman dances for her own pleasure and not in an attempt to satisfy the male gaze:

She can see herself with parted lips and panting, rounded breasts, and a dancing devil in each glowing eye, sway voluptuously to the wild music that rises, now slow, now fast, now deliriously wild, seductive, intoxicating, with a human note of passion in its strain.

This dancing woman is acutely aware of the undermining decorative role she is expected to fill, a common theme in New Woman writing. In a show of solidarity, she wonders if other women feel the same.

Egerton’s association with Wilde, and the consequent discontinuation of The Yellow Book, damaged her reputation. Although she wrote five short story collections, an epistolary collection, one novel, and several plays, she never replicated the success of Keynotes. Her decline coincided with her marriage in 1901 to drama critic and literary agent Reginald Golding-Bright, who was fifteen years her junior. Following his example, she became drama agent to George Bernard Shaw, who produced her first play, and also to Somerset Maugham. Egerton, known by then as Mary Chavelita Bright, passed the final four decades of her long life in relative solitude and died in 1945. As one obituary writer put it:

George Egerton’s death brings back to mind the so-called ‘new woman’ school of fiction of the nineties in which the ‘problems’ of the relations of the sexes for the first time in English literature were put before a somewhat bewildered Victorian public.

Interest in Egerton has grown in recent years but she remains neglected in comparison to contemporaries such as Olive Schreiner, Sarah Grand, and Mona Caird. Yet, her unique brand of feminist writing is worthy of our interest and her revolutionary ideas had a significant influence on several groundbreaking writers, both male and female.

May 12, 2016

Rossetti, Sidonia & Lady Jane Wilde

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, painter, poet and one of the founder members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was born on this day (12 May) in 1828. Oscar Wilde, who was determined to become a poet like his mother, admired Rossetti greatly and strove to associate himself with the Pre-Raphaelite poets, Rossetti in particular. As a young man, his credibility among this group was enhanced greatly by the fact that Lady Jane Wilde had translated the English edition of Willhelm Meinhold’s Sidonia the Sorceress, a key Pre-Raphaelite text, in 1849. Rossetti in particular was said to have referred to and quoted from Jane’s translation ‘incessantly’.

Burne-Jones ‘Sidonia von Bork 1590’

In his review of a 1926 edition of Sidonia, reprinted in Leaves and Fruit, Edmund Gosse stated that it was Rossetti who ‘inoculated the whole Preraphaelite circle with something of his own enthusiasm’ for the book. The association of this text with the Pre-raphaelites was strengthened in 1893, when William Morris’s company Kelmscott Press reprinted and published Jane’s translation of Sidonia the Sorceress. Here’s a beautifully illuminated page from that edition:

reprinted and published Jane’s translation of Sidonia the Sorceress. Here’s a beautifully illuminated page from that edition:

Wilde was fully aware of this connection of course. In a letter sent from Reading jail to his great friend and literary executor Robert Ross in 1896, he mentioned that:

‘my Great-uncle’s Melmoth and my mother’s Sidonia the Sorceress were among the books which entranced him [Rossetti] in his youth.’

Lady Jane Wilde’s translation of Sidonia the Sorceress can be read here. The foremost of Wilde’s Women, her influence on her son Oscar was enormous.

May 9, 2016

Captain Cyril Holland RIP

St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, Richebourg-l’Avoue

On 9 May 1915, Captain Cyril Holland of the Royal Field Artillery was killed in action when shot by a German sniper during the disastrous Battle of Aubers Ridge. He was twenty-nine years old. At the time, his brother Vivian was stationed just three miles away.

Cyril Holland, born Cyril Wilde on 5 June 1885, was the elder son of Oscar and Constance Wilde. A career soldier, in December 1905 he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery and progressed to full Lieutenancy in 1908. He was also a fully qualified interpreter and spoke flawless German.

While serving in India in 1914, Cyril wrote to his brother to explain that, since the death of their father in 1900:

‘my great incentive has been to wipe (the) stain away; to retrieve, if may be, by some action of mine, a name no longer honoured in the land. The more I thought of this, the more convinced I became that, first and foremost, I must be a man. … I am no wild, passionate, irresponsible hero. I live by thought, not by emotion. I ask nothing better than to end in honourable battle for my King and Country.‘

Cyril Holland

For more information click HERE.

May 7, 2016

Speranza’s ‘Saturdays’

Lady Jane Wilde aka Speranza

When Lady Jane Wilde, Oscar’s mother, arrived in London on 7 May 1879, she faced an uncertain future having been left with nothing but debts after the death of her beloved husband, Sir William Wilde. As soon as she recovered her customary ebullience, she revived her Saturday salon and let it be known that she would be at home between five and seven. Visitors came in their droves and, in time, she needed to supplement her ‘Saturdays’ with literary Wednesdays.‘No more successful hostess than Lady Wilde could be found’,

wrote her friend Catherine Hamilton.

‘She managed to put people at their ease, and without talking too much herself, she drew out the best in others’.

Here’s an excerpt from my book, Wilde’s Women, describing these very special gatherings:

When William Butler Yeats persuaded novelist Katharine Tynan to write him a letter of introduction to Lady Jane Wilde, he expressed the hope that he would find her ‘as delightful as her book [Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland]…as delightful as she certainly is unconventional’. To Jane, he was ‘my Irish poet’. In time, he would name Maud Gonne, his great love and muse, ‘The New Speranza’. Yeats, who thought the whole Wilde family ‘very imaginative and learned’, acknowledged that London had few better talkers than Jane. He wrote of her that she ‘longed always perhaps, though certainly amid much self-mockery, for some impossible splendour of character and circumstance’.

Katharine Tynan felt ‘entirely grateful ‘that Jane was ‘very kind to an obscure Irish versifier’. The first gathering she attended took place in the modest house on Park Street in Mayfair that Jane and her elder son Willie took occupancy of towards the end of 1881. Although they had traded up to a more fashionable address, they were obliged to compromise on space and could barely manage the rent on ‘a little house wedged in between another little house and a big public-house at the corner’. When Katharine was greeted by Jane, decked out in ‘a white dress like a Druid priestess, her grey hair hanging down her back’, the first thing that struck her was the gloom. She recounted a humorous anecdote in her memoir, Twenty-Five Years Reminiscences. As she stumbled in the direction Jane indicated: ‘A soft hand took mine and a soft voice spoke. “So fortunate,” said the voice, “that no one could suspect dear Lady Wilde of being a practical joker! There really is a chair”’.

Once they had negotiated the narrow stairway, guests were greeted by Jane or her garrulous elder son, Willie, who bore a striking resemblance to Oscar. On one occasion, an American friend, Anna de Brémont describes how she lost her nerve and hovered on the threshold of the red-tinged semi-darkness until Jane called her by name and rose majestically, ‘her headdress with its long white steamers and glittering jewels giving her quite a queenly air’. The gathering that day consisted of ‘long-haired poets and short-haired novelists – smartly dressed Press women, and not a few richly gowned ladies of fashion’. It was considered, ‘very intellectual’ to be seen at Lady Wilde’s crushes and a cacophony of accents competed to be heard. Local Londoners vied with their Hibernian neighbours and a transatlantic twang dominated at the height of the season when visiting Americans were drawn there by Oscar’s popularity. ‘All London comes to me by way of King’s Road…but the Americans come straight from the Atlantic steamers moored at Chelsea Bridge,’ Jane boasted. Her reception for poet Oliver Wendell Holmes was said to have attracted the cream of literary London.

On that first occasion, Katharine Tynan reported that Jane’s blinds were down in defiance of the bright sunshine outside. Inside, the murk was punctured by the few feeble beams that radiated from a scattering of red-shaded tallow candles ‘arranged so as to cast the limelight on the prominent people, leaving the spectators in darkness’. In almost every account of Jane’s life, it is assumed that vanity was her motivation for keeping her house in darkness so as to distract attention from her ravaged looks. Yet, Catherine Hamilton, among others, testified that her friend remained ‘strikingly handsome’ with ‘glorious dark eyes’ well into her sixties. According to another friend, Henriette Corkran, Jane simply detested ‘the brutality of strong lights’.

Certainly, Jane’s own words support this. She told Oscar that she chose crimson wallpaper punctuated with gleaming golden stars in order to give her home ‘a genial glow’. In her Notes on Men, Women and Books, she expressed approval for Sydney Smith’s aphorism ‘light puts out conversation’, and she also admired romantic poet Samuel Rogers for keeping his dining table in ‘soft shadow’ when most people would have, ‘a vulgar, blinding, flaring glare of gas pouring down upon the heads of the unfortunate, half-asphyxiated guests’.

Although her objective was a ‘genial glow’, the atmosphere at Jane’s Park Street home must have seemed oppressive to some. Pre-Raphaelite painter Herbert Gustav Schmalz, who was rumored to have clashed with Oscar when the latter accused him of leaving one of Jane’s gatherings too early, remembered pastilles of compressed medicinal herbs smoldering on her mantelpiece, and curtain-draped mirrors hanging from ceiling to floor, making it difficult to discern where her room ended and where it began.

As Katharine Tynan’s eyes adjusted to the gloom, she saw that Jane’s walls were crammed with photographs of Oscar in various poses. Their subject arrived shortly afterwards, as he generally did in those early days. In response, the crowd parted, allowing him to bow over his mother’s hand before taking up his favourite position by the chimney-piece, where he struck an aesthetic pose. After a time, he shook off his affectation in order to help his mother pass around the tea. Katherine Tynan declared that, on this and on all such occasions, she found Oscar unfailingly ‘pleasant, kind and interested’; just like his delightful mother.

April 28, 2016

The Sacking of Tite Street

Illustrated Police Budget, May 4, 1895

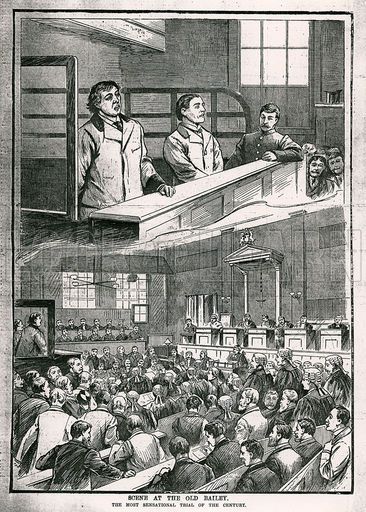

The trial of Oscar Wilde and Alfred Taylor opened on 26 April 1895, in a gloomy courtroom at the Old Bailey, the Central Criminal Court, which was housed at the time in a dispiriting building adjacent to Newgate Gaol. Both men faced counts of gross indecency and conspiracy to procure the commission of acts of gross indecency, although the conspiracy charges were later withdrawn.

Wilde and Taylor had been charged in accordance with Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, commonly referred to as the Labouchère Amendment, which contained no definition of gross indecency and, as a result, outlawed a broad spectrum of homosexual behaviour that was considered less serious than sodomy but was easier to prove. As a consequence, it was regularly exploited by blackmailers.

The ‘Old Bailey’

A bankruptcy sale of the Wilde family’s possessions had been held at their Tite Street home two days earlier. Many items were pilfered during the ensuing melee, including several irreplaceable manuscripts and Wilde’s poignant letters to Constance, which she had kept in a blue leather case. The items that were sold achieved far less than their true value.

An Irish-born publisher gave an account of proceedings to Wilde’s friend and biographer Robert Sherard:

‘I went upstairs and found several people in an empty room, the floor of which was strewn, thickly strewn, with letters addressed to Oscar mostly in their envelopes and with much of Oscar’s easily recognisable manuscript. This looked as though the various pieces of furniture which had been carried downstairs to be sold had been emptied of their contents on to the floor.'[i]

The sacking of the Wildes’ Tite Street home was a terrible humiliation. Wilde’s friend Ada Leverson, one of Wilde’s Women, believed many of those in attendance that day delighted in Oscar’s downfall and wrote:

‘It was already well known that Oscar had bitter enemies as well as a large crowd of friends. And if his chief enemy [Queensberry] was eccentric, many of his jealous rivals were quite unscrupulous.'[ii]

Wilde’s prized books, numbering around two thousand volumes, were bundled together and offered at knockdown prices, making just £130 in total.[iii] Artist James McNeill Whistler sent representatives to buy back a number of his works for less than £40. The nursery was raided and toys belonging to Cyril and Vyvyan were sold, a loss that caused them great distress. In all, the sale raised just £230.

SOURCES:

[i] Sherard, Life of Oscar Wilde, p.359-60

[ii] Leverson, Letters to the Sphinx, p.35

[iii] Donald Mead, ‘Heading for Disaster: Oscar’s Finances’, The Wildean, No. 46, January 2015, p.89

April 22, 2016

Ada Rehan: Wilde’s ‘brilliant & fascinating genius’

Ada Rehan was one of Ireland’s most celebrated actresses but she is barely remembered by us today.

Ada Rehan

Born Delia Crehan in Shannon Street, Limerick on 22 April 1860 (or perhaps 1857), Rehan moved to Brooklyn with her family when she was still a child. Her unconventional name was the result of typographical error made by the Arch Street Theater of Philadelphia, early in her career, when management billed her as Ada C. Rehan. She adopted this as her stage name and gained an international reputation as an excellent Shakespearean actress, doing particularly well in his comedies.

As Rosalind in ‘As You Like It’ (Getty Images)

Statuesque at 5′ 8″, with striking grey-blue eyes and rich dark brown hair, she was much admired. Theatre critic William Winter, who wrote a book about her, recorded that:

‘Her physical beauty was of the kind that appears in portraits of women by Romney and Gainsborough—ample, opulent, and bewitching—and it was enriched by the enchantment of superb animal spirits.’

Of course, there was far more to her than her looks. Oscar Wilde described her as:

‘that brilliant and fascinating genius.’

In 1879, Rehan joined impresario Augustin Daly’s New York based theatre company; she remained his leading lady for twenty years, enjoying enormous success on the stages of America and Europe. For a time, she was considered a worthy rival to the magnificent Sarah Bernhardt.

In September 1891, when Wilde was assembling his cast for the first production of Lady Windermere’s Fan, he wrote to Daly requesting that he consider the part of Mrs. Erlynne for Rehan, insisting:

‘I would sooner see her play the part of Mrs. Erlynne than any English-speaking actress we have, or French actress for that matter,’ [i]

Daly turned him down.

Augustin Daly reading to his company (Rehan is seated on the floor in front of him)

In 1897, after Wilde was released from prison , Daly offered him an advance to write a new play for Rehan, but negotations faltered and Daly died in Paris on 7 June 1899. For Rehan this was as much a personal tragedy as a professional one and she was touched by Wilde’s kindness at this very difficult time, remembering:

‘Oscar Wilde came to me and was more good and helpful than I can tell you – just like a very kind brother…I shall always think of him as he was to me through those few dreadful days’. [ii]

Wilde finally agreed terms with Rehan in February 1900. In return for an advance of £100 with the promised of £200 on acceptance, he agreed to write:

‘a new and original comedy, in three or four acts.’

It was to be produced anonymously:

‘in London at a first-class West-End theatre’. [iii]

Wilde assured Rehan that he would have her play finished by 1 June, but he soon realised that this deadline was wildly optimistic. Although he offered to return her advance, which was long gone by then, he asked that she give some time to raise it. Rehan was disappointed but agreed to the delay. Perhaps inevitably, Wilde never managed to return her money and he was dead before the year was out.

Ada Rehan retired from the stage in 1906, and lived in New York City until her death in 1916. Obituaries were published in the New York Times and the Limerick Chronicle, and she was commemorated more than two decades later when a WWII Liberty ship (a US Navy cargo ship) was named the USS Ada Rehan.

French poet Louis Brauquier with the USS Ada Rehan (from http://www.flickr.com/photos/chartrain)

Ada Rehan is undoubtedly one of Wilde’s Women.

REFERENCES:

[i] Letter to Augustin Daly, August 1897, Complete Letters, p.489

[ii] Robertson, Time Was, p.231

[iii] Russell Jackson, ‘Oscar Wilde’s Contract for a New Play 1900’ in Theatre Notebook, Volume 50, Number 2 contained in Volumes 50-52 (Society for Theatre Research, 1996), p.113

April 20, 2016

Bram Stoker & The Sinking Of RMS Titanic

News of Bram Stoker’s death, on 20 April 1912, was overshadowed somewhat by reports of the sinking of the RMS Titanic five days earlier. This tragedy resonated particularly with Bram’s wife, Florence, who rushed into her husband’s bedroom where he lay dying to tell him of the incident. It must have filled her with dread and evoked painful memories.

RMS Titanic

At 4 a.m. on 13 April 1887, while Florence and her son Noel, aged seven at the time, were sailing from the port of Newhaven in East Sussex to Dieppe on the steamship Victoria, a thick fog had descended, causing the Victoria to hit some jagged rocks. Her bow was ripped open and she sank within two hours. Nineteen passengers lost their lives. As the Victoria went down, there was a scramble to reach the four flimsy lifeboats she carried. Florence and Noel made it on to the third boat and spent twelve hours marooned at sea before they were up picked up by a steam tug and brought ashore at Fécamp in Normandy. The wreck report for the Victoria can be read here and there is a fascinating eyewitness report from the Evening Star newspaper here.

Florence Stoker and her son Noel

Florence was very grateful to have survived the tragedy and the Stoker family made an annual pilgrimage to Fécamp to commemorate the rescue. The incident blighted her life somewhat. When Bram toured America with Henry Irving and his company, he complained of the loneliness of being away from his wife and he always invited her along. Florence, who loved adventure, did join him once, but she never lost her fear of sea travel and the week-long voyage terrified her.

The inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic opened on the day Bram Stoker died, aged sixty-four. It is interesting that his most celebrated work, Dracula, contains an account of the shipwreck of a mysterious Russian ship, albeit under very different circumstances.

For more on Bram, Florence and their relationship read my book Wilde’s Women.

April 19, 2016

Julia Constance Fletcher

In 1876, when she was eighteen, Julia Constance Fletcher, an American-born author who was living in Venice at the time, published A Nile Novel, or Kismet under her pseudonym, George Fleming. It was a huge success and is considered a minor American classic to this day. Months after its publication, Julia bumped into Oscar Wilde, who was holidaying in Rome with friends.

Wilde found Julia absolutely fascinating, particularly when he learned of her brief, tempestuous affair with Byron’s grandson Ralph Gordon Noel Milbanke, thirteenth Baron Wentworth and second Earl Lovelace, who was two decades older than her. There were scandalous whispers of a broken engagement, prompted apparently by Lovelace’s discovery that Julia’s parents were divorced. Afterwards, Lovelace engaged in several desperate but futile attempts to retrieve letters and keepsakes that had belonged to his celebrated grandfather.

There are no confirmed photographs of Julia Constance Fletcher but she is thought to be the woman in the middle

On returning to Oxford, Wilde begged a mutual friend to supply Julia’s address ‘immediately’. Her reply so delighted him that he told his friend she wrote ‘as cleverly as she talks,’ adding, ‘I am much attracted by her in every way’.

When Wilde won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna, he dedicated the published version:

TO MY FRIEND

GEORGE FLEMING,

AUTHOR OF “THE NILE NOVEL,” AND “MIRAGE”

Their friendship endured. A decade later, when he was editor of The Woman’s World, Wilde serialised Julia’s novel The Truth about Clement Ker. In 1894, the year before he was imprisoned, he attended the first night of Mrs. Lessingham, a dramatic exploration of female solidarity that Julia staged in collaboration with pioneering actress Elizabeth Robins.

Julia Constance Fletcher outlived Oscar Wilde by almost four decades. Although she never married, and devoted the latter half of her life to the care of her ailing mother, she had several affairs including one with Siegfried Sassoon’s father, Alfred, who left his wife Theresa for her, although they never lived together.

When war broke out in 1914, Julia worked tirelessly as a volunteer nurse in the military hospitals of Venice. Her wartime services to her adopted nation earned her the Croce de Guerra, the Campaign Ribbon with two stars, the medal for epidemics, the Duke of Aosta’s medal of the Tirza Armata, and the silver medal of military merit. An obituary in The Times of 11 July 1938, lamented the loss of, ‘her brilliant personality and exceedingly witty talk’.

She is deservedly one of Wilde’s Women.

Letter to William Ward, July 1877, Complete Letters, p.58

April 13, 2016

A Poetic friendship: Jane Wilde & William Rowan Hamilton

William Rowan Hamilton

On this day (13 April) in 1855, Jane Wilde met physicist, astronomer and mathematician Sir William Rowan Hamilton at a dinner party hosted by Colonel Thomas Larcom, Under Secretary for Ireland, and his wife Georgina. As both Hamilton and William Wilde were members of the Royal Irish Academy, the former was asked to hand Jane in to dinner. To his astonishment, after practically no introduction at all, this, ‘very odd and original lady’ asked if he would be godfather to her ‘young pagan’. He was further taken aback to learn that this child was to be given:

‘a long baptismal name, or string of names, the two first of which are Oscar and Fingal!’

Although he declined, Jane bore no grudge, and endeared herself by expressing admiration for poetry composed by his late sister Eliza. The next time they met, Hamilton presented Jane with an inscribed copy of Eliza Hamilton’s Poems.

Dunsink Observatory, Dublin

Over lunch at Dunsink Observatory, Hamilton’s home, Jane informed her host that baby Oscar had been baptised the previous day and they drank a toast to his health. Afterwards, he gave her a tour of his atmospheric house, which Eliza had believed to be haunted. Jane expressed a hope that this was true. Yet, although she liked and admired Hamilton, she was unable to hide her resentment at the wealth his eminence had secured and declared:

‘Let a woman be as clever as she may, there is no prize like this for her!’

Hamilton’s correspondence with Jane demonstrate a great regard for her intellect. He felt free to discuss any topic with her and included quotations in Latin and Greek, which he acknowledged need not be translated. He admired her noble nature and regarded her as an ‘entirely truthful person’. His long, rambling letters could be quite flirtatious. In one, he described her as:

‘a very remarkable, a very interesting, and (if I could be forgiven for adding it) a very lovable person.’

Yet, he kept his distance and congratulated her on ‘being so happily married’.

Jane Wilde

The characteristics William Rowan Hamilton admired in Jane Wilde were not generally prized in Victorian women. Describing her as ‘almost amusingly fearless and original and averse’, he admired her determination to ‘make a sensation’. Although their politics were at variance, this formed no barrier to their friendship. While his heart ‘throbbed with sympathy, for the great British Empire’, he argued that this had the advantage of allowing him to understand Jane better, since they shared the experience of sympathising with a whole nation.

Hamilton was an accomplished poet who had, in his youth, been mentored by William Wordsworth. When Jane sent him her sixteen-stanza Shadows from Life, he praised it as ‘wonderfully beautiful’ but suggested several changes, which she made. He also shared it with poet Aubrey de Vere, who declared:

‘She certainly must be a woman of real poetic genius to have written anything so beautiful and also so full of power and grace as the poem you showed me’.

De Vere went on to urge:

‘for the sake both of poetry and Old Ireland you must do all you can to make her go on writing, and publish a volume soon.’

When Hamilton invited both to a ‘Feast of Poets’, he warned Jane not to allow De Vere to convert her to Catholicism, which she found fascinating.

Sources:

Chapter 3 of Wilde’s Women by Eleanor Fitzsimons

Robert Graves. Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, knt., LL. D., D.C.L., M.R.I.A., Andrews professor of astronomy in the University of Dublin, and royal astronomer of Ireland, etc. etc.: including selections from his poems, correspondence, and miscellaneous writings. Volume III, (Dublin, Hodges, Figgis, & Co., 1882-89)

Terence de Vere White. The Parents of Oscar Wilde (London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1967),

April 8, 2016

Beatrix Potter: Teenage Celebrity Spotter

I love stumbling across little anecdotes and insights into the life of Oscar Wilde. Sometimes their source is extraordinary. Take for instance two entries in the journal of Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), author, illustrator, natural scientist, and conservationist. I included them in Wilde’s Women.

Young Beatrix Potter (Hulton Archive, Getty Images)

Potter’s father, Rupert Potter, a lawyer and a keen amateur photographer, was a close friend of the painter Sir John Everett Millais. Beatrix was just seventeen-years-old when she recorded the following in her journal of 1884. Oscar and Constance had been married for less than two months by then:

Saturday, July 12th. Papa and mama went to a ball at the Millais’ a week or two since. There was an extraordinary mixture of actors, rich Jews, nobility, literary, etc. [Cartoonist George] Du Maurier had been to the ball the week before, and Carrie Millais said they thought they had seen him taking sketches on the sly. Oscar Wilde was there. I thought he was a long, lanky melancholy man, but he is fat and merry. His only peculiarity was a black choker instead of a shirt-collar, and his hair in a mop. He was not wearing a lily in his buttonhole, but, to make up for it, his wife had her front covered with great water-lilies

Sir John Everett Millais by Rupert Potter

In 1885, when Beatrix recorded the following, Constance would have been six months pregnant with Cyril:

Sunday March 15th. Saw Oscar Wilde and his wife just going into the Fine Arts to see the Holman Hunt. He is not peculiar as far as I noticed, rather a fine looking gentleman, but inclined to stoutness. The lady was strangely dressed, but I did not know her in time to see well.

Source: Beatrix Potter & Glen Cavaliero (Ed.), Beatrix Potter’s Journal (Harmondsworth, Warne, 1986). A fascinating book full of remarkable observations!