Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 4

January 14, 2017

Oscar Wilde & The Davis Sisters

The Wilde family was prominent in the Dublin social scene, and well connected with other wealthy Dublin families. One such was the Davis family. Although both Hyman Davis, a dentist, and his wife, Isabella, were Londoners, they spent many years in Dublin and several of their eight children were born there. In the late 1870s, both Willie and Oscar were friendly with Dublin-born James ‘Jimmy’ Davis who, in a chequered career, was alternately a theatre writer, racing correspondent, theatre critic and solicitor.

Jimmy’s younger sister Eliza, who made her name as fashion columnist ‘Mrs Aria’, recorded her recollections of Oscar and Willie in her memoir, My Sentimental Self (1922).

Both Oscar Wilde and Willie Wilde became frequent visitors, and in a public garden which spread its ill-kept lumpish lawn behind our dwelling we often played tennis together: Willie in a shirt showing some desire to be divorced from the top of his trousers, and Oscar in a high hat with his frock-coat tails flying and his long hair waving in the breeze.

Their connection did not end there. Eliza made her name as a journalist, editor of fashion magazine The World of Dress, and author of books on fashion and motoring. When she became involved in a long-term affair with Henry Irving, she suggested, to no avail, that he stage Wilde’s second play, The Duchess of Padua.

Her intervention on Oscar’s behalf may be attributable to their youthful friendship but may also have been rooted in the fact that her older sister Julia, also a participant in their tennis parties, was given her first break in journalism as a result of an attempt to parody Oscar’s work. Eliza wrote:

Julia’s attempt at a parody of a villanelle by Oscar Wilde which had appeared in The World led to an interview with Edmund Yates [editor], who found in it some excuse for encouraging her to take up writing as a career.

adding,

It is a coincidence that her first published lines should have owed their existence to Oscar Wilde.

Eliza Davis Aria gazes at a photo of her sister Julia

In 1906, six years after Oscar’s death, Julia, writing as Frank Danby, published a novel, The Sphinx’s Lawyer. In My Sentimental Self, Eliza described this book as Julia’s attempt ‘to defend the undefendable Oscar Wilde’.

In an astonishing preface to The Sphinx’s Lawyer, addressed to her brother Jimmy, who wrote under the name Owen Hall, and who had fallen out spectacularly with Oscar, Julia declared:

‘Because you “hate and loathe” my book and its subject, I dedicate it to you’. For, incidentally, your harsh criticism has intensified my conviction of the righteousness of the cause I plead, and revolt from your narrow judgment has strengthened me against any personal opprobrium that such pleading may bring upon me’

In the pages that follow, Oscar appears in the guise of Algernon Heseltine, a man treated unjustly by society because he ‘was not as others’ on account of his genius; ‘the applause changed to low suspicious muttering’, Julia observed. It seems certain, given the title of her novel, that Julia’s qualified defence of Oscar was also connected to her great friendship with Ada Leverson, Wilde’s ‘Wonderful Sphinx’.

Yet, although Julia lauded Oscar’s genius and characterised him as a martyr, The Sphinx’s Lawyer was no vindication since she suggested that Heseltine was mad and should ‘have been placed in safety, kept from spreading his disease, from working evil’.

Her descriptions of Oscar, as ‘Heseltine’, facing his accusers, are worth reading:

The fire of his own genius had burnt Algernon’s youth. The light that blazed about him obscured for him the minor rules of meaner men. He saw more largely, amazing visions thronged, all sense of proportion became lost. He was not as others. He felt that, and at first the dazzled world which his personality fascinated saw it too, and applauded. When the applause changed to low suspicious muttering, he became more flamboyant; he was supremely conscious of his gifts.

The end was not swift, yet it was upon him before he knew. He stood before his accusers in the dock as a child might have stood, impudent, bewildered, irresponsible. Those for whom he and his ailments held no meaning found him guilty, and sentenced him to a terrible end. He was as a sick child, morally, mentally, physically, dazed, and failing.

For his fine hands, which had penned epic and philosophy, poem, and drama, there were bundles of tarred oakrum [sic]. When he failed over his task there was darkness, more appalling solitude, less food, stripes. It ought to be incredible, but the whole bare truth is beyond it. The personal degradation to which this man of genius was subjected, the outrages to his glimmering sense and dying manhood, made a martyr to him to those who knew. (104–05)

Sources:

Mrs. Aria London, My Sentimental Self (London, Chapman & Hall, 1922)

Frank Danby, The Sphinx’s Lawyer (New York, F.A. Stokes Company, 1906)

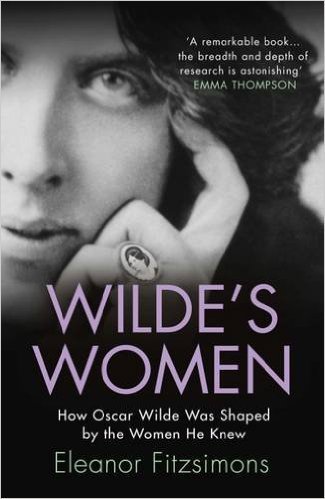

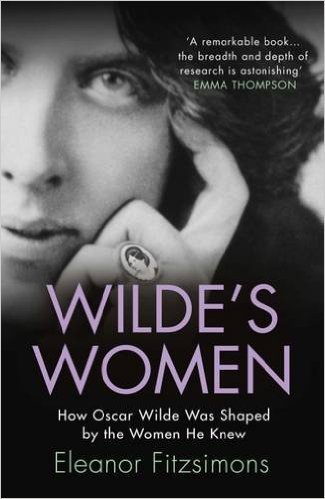

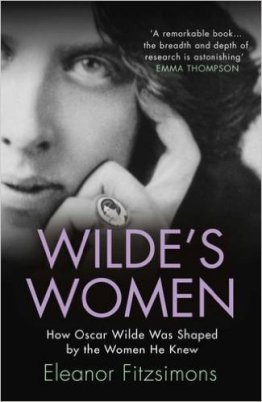

Eleanor Fitzsimons, Wilde’s Women (London, Duckworth & Co., 2015)

January 2, 2017

‘What has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught!’

An excerpt from Wilde’s Women:

[image error]

In his ‘Literary and Other Notes’ column in the January 1888 issue of The Woman’s World, the magazine he edited from 1887 to 1889, Oscar Wilde praised Women and Work, an essay from poet and philanthropist Emily Jane Pfeiffer. He described Pfeiffer’s work, which was subtitled ‘An Essay Treating on the Relation to Health and Physical Development, of the Higher Education of Girls, and the Intellectual or More Systematised Effort of Women,’ as:

‘a most important contribution to the discussion of one of the great social problems of our day’.

Wilde welcomed in particular Pfeiffer’s refutation of Professor George Romane’s preposterous assertion that men and women should be ‘mentally differentiated,’ as outlined in his essay ‘Mental Differences Between Men and Women’.

In order to illustrate his opposition to Romane, Wilde quoted Daniel Defoe:

‘What has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught!’

[image error]

Source:

Oscar Wilde, ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, Volume I, January 1888, pp.135-6

Defoe’s ‘The Education of Women’ is included in English essays from Sir Philip Sidney to Macaulay (1910) F. Collier & Son, p.159

December 24, 2016

‘Nellie Sickert, from her friend Oscar Wilde

On 2 October 1879, Oscar Wilde sent a gift to his young friend Helena Sickert, aged sixteen. It was a copy of Selected Poems of Matthew Arnold, inscribed to ‘Nellie Sickert, from her friend Oscar Wilde’; he described it in the letter he enclosed with the package:

Dear Miss Nellie,

Though you are determined to go to Cambridge, I hope you will accept this volume of poems by a purely Oxford poet. I am sure you know Matthew Arnold already but still I have marked just a few of the things I like best in the collection, in the hope that we may agree about them. ‘Sohrab and Rustom’ is a wonderfully stately epic, full of the spirit of Homer, and ‘Thyrsis’ and ‘The Scholar Gypsy’ are exquisite idylls, as artistic as ‘Lycidas’ or ‘Adonais’: but indeed I think all is good in it.”

Oscar encouraged Helena’s love of poetry and had recited his poem ‘Ravenna’ to her as they sat beneath the gnarled and fragrant apple trees at her home in Neuville near Dieppe in the summer of 1878.

During that holiday, he also invented, ‘poetical nonsense of exactly the right blend’ for her little brothers, Oswald aged seven and Leo, aged five, before joining in with the rough and tumble of their games, as he would one day with his own two sons.

Struck by his unfailing ‘joyousness’, Helena would later recall:

I have never known any grown person who laughed so wholeheartedly and who made such mellow music of it.

When the Sickerts moved to London, Oscar became a welcome visitor who ‘poured out the riches of his talk’ for hours at a time. In her memoir, I Have Been Young, Helena conjured up those delightful days, writing:

When I try to recapture the enchantment I see the big indolent figure, lounging in an easy chair, his face alive with delight in what he was saying, pouring out stories and descriptions whose extravagance piled up and up till they toppled over in a wave of laughter….I can’t remember any of his countless witty sayings, but his laughter I shall hear till I die. His extravaganzas had no end, his invention was inexhaustible, and everything he said was full of joy and energy.

She recognised that the only stimulus Oscar needed to tell a story was to be in the company of good listeners, and she describes him:

…his indolent figure, lounging in an easy chair, his face alive with delight in what he was saying, pouring out stories and descriptions, whose extravagance piled up and up.

Once, when she allowed her scepticism to show, he enquired playfully: ‘You don’t believe me, Miss Nelly? I assure you… well, it’s as good as true.’

Helena Sickert, later Swanwick, went on to have a long and very remarkable life…but that’s another story.

Sources:

H. M. Swanwick, I Have Been Young (London: Victor Gollancz, 1935), p.65

The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. Eds: Merlin Holland & Rupert Hart-Davis, p.83

Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde was shaped by the women he knew by Eleanor Fitzsimons

[image error]

December 22, 2016

Sarah & Maurice Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt with her son Maurice

On 22 December 1864, Sarah Bernhardt gave birth to Maurice, her only child. She named him after her maternal grandfather Moritz Bernardt (the original spelling), although it is entirely possible that she never once met that unreliable vagabond.

Maurice’s father was generally assumed to be Belgian nobleman Charles Joseph Eugène Henri Georges Lamoral, Prince de Ligne, but Sarah refused to be drawn on this and joined in with humorous speculation as to her son’s paternity.

She seemed refreshingly unabashed by her status as a single mother; she gave Maurice her last name and never attempted to conceal his relationship to her, although many women of her time bowed to societal pressure and concealed their children from disapproving eyes.

For more on Sarah and her son Maurice, read any of the following:

Elaine Aston. Sarah Bernhardt: A French Actress on the English Stage.Oxford: 1989

Ruth Brandon. Being Divine: A Biography of Sarah Bernhardt. London: 1991

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale. The Divine Sarah: A Life of Sarah Bernhardt. New York: 1991

Or Wilde’s Women.

[image error]

December 15, 2016

E. Nesbit: ‘A Very Pure and Perfect Artist’

I’m working on a biography of E. Nesbit at the moment and deriving great enjoyment from researching her fascinating life! She was my favourite author in childhood and it is such a pleasure to revisit her stories. Although she’s best known for her children’s stories, her first literary love was poetry, and she sought the approval of Oscar Wilde.

[image error]

Edith Nesbit

In 1886, Nesbit sent Wilde a copy of her collection Lays and Legends and he responded with an encouraging letter, lauding her ambition to ‘give poetic form to humanitarian dreams, and socialist aspirations’.

In Wilde’s very first ‘Literary and Other Notes’ editorial for issue one of The Woman’s World, in November 1887, he reviewed Women’s Voices, an anthology of poetry edited by Elizabeth Sharp, and he described ‘Mrs. Nesbit’ as ‘a very pure and perfect artist’.

In ‘Poet’s Corner’ in the Pall Mall Gazette, Wilde reviewed Nesbit’s ‘remarkable’ collection Leaves of Life. Describing ‘many of her poems’ as ‘true works of art’, he praised her keen eye for nature, ‘exquisite sense of colour’, and ‘delicate ear for music’.

[image error]

Wilde also published three of Nesbit’s poems in The Woman’s World: ‘Christmas Roses’ in December 1888, ‘The Soul to the Ideal’ in July 1889, and ‘Equal Love’ in June 1890. Here’s ‘Christmas Roses’ for the season that’s in it.

THE summer roses all are gone–

Dead, laid in shroud of rain-wet mould;

And passion’s lightning time is done,

And Love is laid out white and cold.

Summer and youth for us are dead,

What do old age and winter bring instead?

They bring us memories of old years,

And Christmas roses, cold and sweet,

Which, washed by not unhappy tears,

I bring and lay beside your feet,

With gifts that come with flowers like these–

Friendship, remembrance of our past, and peace!

Edith Nesbit

More on E. Nesbit and Oscar Wilde can be found in Wilde’s Women.

[image error]

December 12, 2016

The Very Brilliant Miss Mary Story

In his ‘Literary and Other Notes’ in the December 1887 issue of The Woman’s World, the magazine he edited, Oscar Wilde took the opportunity to highlight the success of a Miss Story, the daughter of a Northern Irish clergyman, who had been awarded a literature scholarship by the Royal University in Ireland. She was to receive £100 a year for five years.

Wilde remarked:

It is pleasant to be able to chronicle an item of Irish news that has nothing to do with the violence of party politics or party feeling, and that shows how worthy women are of that higher culture and education which has been so tardily, and in some instances, so grudgingly granted to them.

The Sixth Annual Report of the Royal University of Ireland confirms:

In modern literature, experimental science, and medicine, the highest honours have been carried off by women. In the first of these subjects a young lady – Miss Mary Story – has won the studentship – the highest honour that can be obtained in this University.

Sources:

Oscar Wilde, ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, Volume I, December 1887, p.85

Sixth Annual Report of the Royal University of Ireland, 1888

Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde was Shaped by the Women he Knew by Eleanor Fitzsimons

December 7, 2016

Willa on Wilde

Pulitzer Prize winning author Willa Cather was born in Back Creek Valley (a small farming community close to the Blue Ridge Mountains) in Virginia on 7 December 1873. In September 1895, four months after Oscar Wilde’s conviction and imprisonment, she wrote about him in her (on this occasion unsigned) weekly column for The Courier. She was not at all kind:

Source:

Willa Cather, ‘The Passing Show’, The Courier (Lincoln Nebraska), 28 September 1895, p.7. As featured in Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde was Shaped by the Women he Knew by Eleanor Fitzsimons.

Margot Asquith & The Star Child

In her memoir More Memories, socialite Margot Tennant, who was by then the wife of Scottish Liberal M.P. Herbert Asquith, wrote:

‘On 7th December [1891] I received a letter from Oscar Wilde, saying he had dedicated his new story The Star Child to me’.

Margot first met Oscar at a garden party given by Lady Archibald Campbell. In her memoir, she remembered him as a

‘large, fat, floppy man, in unusual clothes sitting under a fir tree surrounded by admirers’.

Oscar was recounting a ‘brilliant monologue’ at the time in which he compared himself playfully,to Shakespeare. Margot felt compelled to join his circle and afterwards they struck up a lasting friendship while strolling around Janey Campbell’s lovely gardens.

Recalling a ‘brilliant luncheon’ Margot hosted with her husband, poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt wrote in My Diaries; being a Personal narrative of Events 1888-1914:

‘Afterwards, when the rest had gone away, Oscar remained, telling stories to me and Margot’.

During the autumn of 1889, Margot invited Oscar to stay at Glen, her family’s country estate, although she decided he must dislike the countryside since he spent ‘most of his time in the house,’ where he ‘wrote several aphorisms and poems on loose sheets of paper’. The fact that she managed to lose these sheets is indicative of the poor regard she developed for his work: ‘Speaking for myself’, she confessed, ‘I do not think his stories, plays, or poems will live’. Yet, her letter indicates that she was pleased when he dedicated ‘The Star Child’ to her.

This tale, which is included in A House of Pomegranates, appears to borrow from Irish mythology; Wilde’s charmed child possesses some of the qualities associated with the Sidhe, a fairy race described beautifully by his mother, Jane, in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. In Wilde’s tale, two poor woodcutters happen upon a beautiful infant who appears to have fallen from the heavens. Although he grows up to be cruel and haughty, the boy is redeemed once he passes through a series of trials that oblige him to confront his wickedness.

Riders of the Sidhe by John Duncan

Wilde’s tales rarely have conventionally happy endings; although the young man becomes king and rules for three years, his munificence barely touches the unequal society he presides over and he is replaced by a series of despots. The moral of the story is that no matter how beneficent the ruler, the people cannot progress without self-determination.

Margot Asquith too was close to the seat of power. Within months of the publication of A House of Pomegranates, her husband was appointed Home Secretary and in this role he acted as Wilde’s prosecutor. A distant relative by marriage of Lord Alfred Douglas, Margot would have nothing to do with Oscar when he needed her most, although she did remain a loyal friend to Robbie Ross.

You can read ‘The Star Child’ here.

Sources:

Eleanor Fitzsimons, Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde was Shaped by the Women he Knew (Duckworth, 2015)

Margot Asquith, More Memories (London, Cassells & Company,1933)

Dr. Anne Markey, Oscar Wilde’s Fairy Tales: Origins and Contexts (Irish Academic Press, 2011)

December 3, 2016

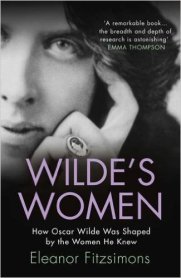

The Funeral of Oscar Wilde 3 December 1900

Oscar Wilde was buried at Bagneux cemetery at 9am on 3 December 1900. His funeral mass was read by Fr. Cuthbert Dunne at the church of Saint-Germain-des- Prés in the presence of fifty-six people, among them ‘five ladies in deep mourning’.

Robbie Ross identified four of these women*: American journalist, novelist, poet and singer Anna de Brémont and her maid; Mme Stuart Merrill, wife of the American symbolist poet who had raised a petition for Oscar’s release; and ‘an old servant girl of Oscar Wilde’s wife’. Richard Ellmann identified the fifth as a Miriam Aldrich, although Horst Schroeder disputes this.** At the head of Oscar’s coffin, Ross placed a wreath of laurels inscribed

‘A tribute to his literary achievements and distinction’

It bore the names of

‘those who had shown kindness to him during or after his imprisonment’

among them Ada Leverson and Adela Schuster. Lord Alfred Douglas interrupted a shooting holiday in Scotland to turn up as chief mourner. According to Wilde’s biographer Richard Ellmann there was an ‘unpleasant scene’ at the graveside that he speculates may have been ‘some jockeying for the role of principal mourner’. He writes that while Wilde’s coffin was being lowered, Douglas almost fell into the grave.

Wilde’s remains were transferred to Père Lachaise in July 1909.

SOURCE:

*From ‘Robert Ross Gives a New Version of the Last Days of Oscar Wilde’, New York Times, 13 March 1910. Also, Anna de Brémont confirms her presence in Oscar Wilde and his Mother.

**Horst Schroeder, Additions and corrections to Richard Ellmann’s Oscar Wilde (Braunschweig Selbstverl, 2002), p.216

Belle Strong & Mr. Wilde

Brilliant Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, author of author of Treasure Island (1883), Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Kidnapped (1886) and much more, died of a cerebral hemorrhage on 3 December 1894, aged just 45.

Oscar Wilde admired Stevenson greatly and called him ‘that delicate artist in language’. In prison, he requested copies of his novels. He also had a connection with Stevenson’s stepdaughter Belle Strong.

Isobel ‘Belle’ Osbourne Strong Field

Stevenson was very fond of Belle and described her thus in 1892:

She is my wife’s daughter, my secretary, my amanuensis, my woman-Friday on my desert island, my finder of things, my last assistance, my oasis, my staff of hope, my grove of peace, my anchor, my haven in a storm. She’s Belle, I suppose.

Here’s an excerpt from Wilde’s Women describing Wilde’s encounter with Belle in San Francisco in 1882:

In San Francisco, Oscar was entertained by Belle Strong, stepdaughter of Robert Louis Stevenson, who hosted a party in his honour in the studio of her artist husband, Joe. Belle thought Oscar ‘very impressive’, adding:

He was charming. His enthusiasm, his frank sincerity, dispelled at once any constraint we may have felt at meeting such a distinguished stranger. We didn’t know that we were listening to one who was acknowledged to be the wittiest man in London. We were exhilarated by his talk, gay, quick, delightfully cordial and almost affectionately friendly.

It was a memorable occasion: ‘When he left we all felt we had met a truly great man’, Belle decided.

Source:

Isobel Osbourne Field, This Life I’ve Loved (New York, Longmans, Green, 1938), p.148

http://robert-louis-stevenson.org/