Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 13

November 18, 2015

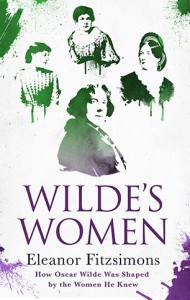

Win a Copy of Wilde’s Women

November 9, 2015

I wrote about a brilliant, exiled Irish writer whose life unravelled – not Oscar but Maeve Brennan

It sometimes takes an outsider’s gaze to capture the essence of a place with an authenticity that lies beyond the sight of the indigenous observer. For this reason, it should have come as no great surprise to readers of The New Yorker when the Long-Winded Lady, columnist and faithful, if eccentric, documenter of life in the eponymous city, was unmasked as Irishwoman Maeve Brennan, an immigrant who had arrived in her mid-twenties. John Updike, among others, realised that this watchful interloper ‘brought New York back to The New Yorker’. In her whimsical contributions to the exalted ‘Talk of the Town’ column, Brennan was rare in establishing a distinct persona, and unique in ensuring that this voice was a female one. Stylish, ambitious and armed with a waspish wit that conjured up recollections of Dorothy Parker, her personality contrasted violently with that of her passive, suburbanite alter-ego.

Between 1954 and 1968, Brennan documented a city in flux, a place where the wrecker’s ball swung in perpetual motion as residents embraced a post-war transience. She too drifted: a self-confessed ‘traveller in residence’, she hopped from short-lease apartment to anonymous hotel suite, or borrowed summer houses from glamorous friends like Gerald and Sara Murphy, Fitzgerald’s models for the Divers in Tender is the Night. In her wake she left little beyond a miasma of cigarette smoke and a trace of expensive scent. As one-time editor at The New Yorker Gardner Botsford observed, Brennan could, ‘like the Big Blonde in the Dorothy Parker story … transport her entire household, all her possessions and her cats – in a taxi’. In her story ‘The Last Days of New York City’, published in The New Yorker in 1955, Brennan confessed: ‘All my life, I suppose, I’ll be running out of buildings just ahead of the wreckers’.

Although rarely absent from New York State, Brennan used fiction to return to her native Ireland, which she had left while still in her teens. In The Visitor, her posthumously published novella, she explains why: ‘Home is a place in the mind,’ she writes, ‘when it is empty it frets’. Yet, her memories were never those of a misty-eyed romantic. Born within a year of the failed Easter Rising of 1916, to a staunch Republican father who was in prison at the time but was later appointed Secretary of the Irish Legation to Washington, Brennan was tangled up in political turmoil for much of her early life. The precariousness of her existence and the ever-present threat of displacement seep into stories shot through with anxiety and unease. In ‘The Day We Got Our Own Back’, from The New Yorker in 1953, Brennan documents how she watched wide-eyed as her family home was raided:

One afternoon some unfriendly men dressed in civilian clothes and carrying revolvers came to our house, searching for my father, or for information about him.

Throughout her life, she had a horror of being pinned down and she rarely made firm arrangements.

Conventional boundaries between memoir and fiction are rarely observed in Brennan’s revealing Irish stories, many of them collected posthumously in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin, a book compared favourably to Joyce’s Dubliners. Although these tales of lower-middleclass Dublin life appear superficially innocuous, they revealed an unfamiliar malevolence to second– and third-generation Irish-Americans who hankered after a mist-shrouded holy land. Her characters operate furtively, seeing out their thwarted lives in the shadow cast by a stultifying and spiritless Catholic Church.

Conventional boundaries between memoir and fiction are rarely observed in Brennan’s revealing Irish stories, many of them collected posthumously in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin, a book compared favourably to Joyce’s Dubliners. Although these tales of lower-middleclass Dublin life appear superficially innocuous, they revealed an unfamiliar malevolence to second– and third-generation Irish-Americans who hankered after a mist-shrouded holy land. Her characters operate furtively, seeing out their thwarted lives in the shadow cast by a stultifying and spiritless Catholic Church.

From the safety of cosmopolitan New York, Brennan time travelled back to darkened confessionals where guilt-ridden children cowered under the gaze of a vengeful deity, and to the ante-chamber of an enclosed convent where a bereft mother strained to discern the voice of a lost daughter who sang in praise of her unearthly spouse. Teaching nuns, capricious in their accusations, note that the young Brennan was headstrong and wilful, traits that are inappropriate in Irish womanhood. Decades later, in ‘Lessons and Lessons and More Lessons’ from The New Yorker, Brennan described how, in a city where the ‘three-martini lunch’ is commonplace, she hid her glass instinctively when two nuns entered the Greenwich Village restaurant she frequented.

In New York, Brennan embraced her ‘otherness’; as one colleague observed, ‘She wasn’t one of us. She was one of her!’ To strangers, she could appear hard-edged and watchful, yet friends found her warm and generous, voluble and funny. Everyone agreed that she was beautiful. Barely five feet tall and beanpole slim, she looked younger than her years and compensated with vertiginous heels. She tottered along the robustly masculine corridors of The New Yorker offices at West Forty-Third Street, make-up immaculate, hair neatly coiffed and carefully chosen costume exquisitely cut, with a fresh flower in her lapel, generally a rose. She had the ceiling of her office painted Wedgwood blue and threw open her door while she tap-tapped away on her typewriter, a curlicue of smoke rising from the ever-present Camel clenched between her fingers. Her language was defiantly fruity, and the mischievous notes that she slipped under the doors of her male colleagues elicited great explosions of laughter: ‘To be around her was to see style being invented,’ recalled her friend and editor William Maxwell.

An ill-fated stint as fourth wife to fellow New Yorker writer St. Clair McKelway – a hard-drinking, mentally frail man – took her to bohemian Sneden’s Landing, a community of artists and writers that nestled alongside the Hudson in upstate New York. Brennan recast it as ‘Herbert’s Retreat’, a rarefied enclave where privileged New Yorkers partied under the watchful gaze of their derisive Irish servants. With an insider’s familiarity, Brennan used her stories to juxtapose the prudent Catholicism of her countrywomen with the flagrant immorality of their employers. As the beautiful and sophisticated daughter of a diplomat, Brennan enjoyed a status that allowed her to pass in society, yet she had rubbed shoulders with girls who would enter domestic service and must have felt a sneaking solidarity with them. As a former fashion writer with Harper’s Bazaar, it apparently amused her greatly when the trappings of Irish peasantry – shawls and tweed and tealeaves – were adopted as status symbols by wealthy American women.

At times, Brennan grasped onto the trappings of Irishness with a fervour that suggested desperation and displacement. She drank tea obsessively, and although her rented homes rarely featured a kitchen, she insisted on an open fireplace, considering a fire to be a living thing, company almost. When her marriage failed in 1959, she embraced a solitary life, borrowing houses in the Hamptons and walking the Atlantic beach with her dog, Bluebell before returning to the twin comforts of a scalding hot cup of tea and a roaring fire, which she shared with several cats, ‘small heaps of warm dreaming fur all over the furniture and the floor’. In summertime, when the Hamptons filled up, she would return to New York City or travel home to Ireland.

During her chaotic, alcohol-soaked marriage, Brennan wrote little of any worth. When one devoted reader requested more Maeve Brennan stories, she had her editor write to explain that she had shot herself when she was ‘drunk and heartsick’. However, the 1960s heralded a period of intense productivity. Several of her finest stories, set in Dublin and Wexford, feature Rose and Hubert Derdon, a couple who endure a dispiriting marriage: she is furtive and priest-ridden, while he ‘wore the expression of a friend, but of a friend who is making no promises’. Carefully crafted, these stories represent a stingingly accurate documenting of the disappointments that ambush even the most virtuous at every turn. Many of the stories from this period were published in In and Out of Never-Never Land. A number of stories from this collection are set in Forty-eight Cherryfield Avenue, in the well-to-do Dublin suburb of Ranelagh, the home she occupied as a child; William Maxwell described it as her ‘imagination’s home’.

Brennan’s story ‘The Eldest Child’ was selected for Best American Short Stories 1968. Yet even as her writing elicited fresh acclaim, her life began to unravel and she drifted, physically and mentally, becoming unkempt, erratic and paranoid. Homeless and debt-ridden, she took to sleeping on a couch in the ladies room at The New Yorker offices, and she grew paranoid that her toothpaste had been laced with cyanide. When she was institutionalised for a time, one friend testified that she became very Irish, as if the years had fallen away, and with them the carefully crafted veneer. She was discharged once she had established a pharmaceutically induced equilibrium, but she could not be relied on to take her medication and drifted once more, losing touch with friends and colleagues. She was nervously tolerated at the offices of The New Yorker as a legacy of affection and with respect for her talent, but her behaviour grew erratic: she once nursed a sick pigeon in her office and, in a more sinister episode, wrecked the offices of a number of colleagues. Sometimes, she stood outside, handing out cash to bewildered passers-by. Inevitably, she produced little that was worthy of publication. Yet ‘The Springs of Affection’, her longest and, arguably, most powerful story, appeared in The New Yorker in March 1972. Although it is almost entirely autobiographical, Brennan twisted the facts in such a fashion that one aunt was prompted to write the words ‘greatly changed for the worse’ on a photograph of her brilliant niece.

Brennan’s story ‘The Eldest Child’ was selected for Best American Short Stories 1968. Yet even as her writing elicited fresh acclaim, her life began to unravel and she drifted, physically and mentally, becoming unkempt, erratic and paranoid. Homeless and debt-ridden, she took to sleeping on a couch in the ladies room at The New Yorker offices, and she grew paranoid that her toothpaste had been laced with cyanide. When she was institutionalised for a time, one friend testified that she became very Irish, as if the years had fallen away, and with them the carefully crafted veneer. She was discharged once she had established a pharmaceutically induced equilibrium, but she could not be relied on to take her medication and drifted once more, losing touch with friends and colleagues. She was nervously tolerated at the offices of The New Yorker as a legacy of affection and with respect for her talent, but her behaviour grew erratic: she once nursed a sick pigeon in her office and, in a more sinister episode, wrecked the offices of a number of colleagues. Sometimes, she stood outside, handing out cash to bewildered passers-by. Inevitably, she produced little that was worthy of publication. Yet ‘The Springs of Affection’, her longest and, arguably, most powerful story, appeared in The New Yorker in March 1972. Although it is almost entirely autobiographical, Brennan twisted the facts in such a fashion that one aunt was prompted to write the words ‘greatly changed for the worse’ on a photograph of her brilliant niece.

Although Brennan continued as an occasional contributor to ‘Talk of the Town’, her offerings arrived out of the blue with no indication of where she was when she wrote them. In her final outing as the Long-Winded Lady, in January 1981, she described how, walking along Forty-Second Street, she had sidestepped a shadow that she recognised as ‘exactly the same shadow that used to fall on the cement part of our garden in Dublin, more than fifty-five years ago’. That year, she turned up at the offices of The New Yorker, grey-haired and unkempt, and sat quietly in reception on two consecutive days, but no one appeared to recognise her. Maeve Brennan died of heart failure in a New York nursing home on 01 November 1993; she was seventy-six. By then, she had descended into an imaginary existence in which she appeared unaware of her status as a celebrated writer.

Excluded from the canon of important Irish writing for years, she has enjoyed a posthumous revival. Two collections of short fiction, The Springs of Affectionand The Rose Garden, and her revealing novella, The Visitor, are still in print, as is a collected edition of Long-Winded Lady pieces. Jonathan Cape published Angela Bourke’s biography Maeve Brennan: Homesick at The New Yorker in 2004. Since then, several new plays and collections have referenced the work of this significant Irish writer.

~

Photo of Maeve Brennan © Yvonne Jerrold

November 2, 2015

Wilde about Keats

I’m so proud to be a contributor to the wonderful Romanticism Blog – it’s a really brilliant source of information on the Eighteenth Century and the Romantic poets. My latest post for the is a tie-in with my book Wilde’s Women and can be read here or below:

In July 1877, subscribers to the Irish Monthly, a publication subtitled ‘A Magazine of General Literature’, were treated to an entertaining and scholarly article headed ‘The Tomb of John Keats’. The author, a 22-year-old Dubliner, was an undergraduate at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was reading Literae Humaniores, the university’s undergraduate course in Classics. This was his first published prose article and his name was Oscar Wilde.

In this moving tribute to the young poet, which can be read here, Wilde, an avid fan, introduced Keats as ‘one who walks with Spenser, and Shakespeare, and Byron, and Shelley, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning in the great procession of the sweet singers of England’. While allowing that the resting place of ‘this divine boy’, which he had visited earlier that year, was surrounded by beauty, Wilde insisted that Keats’ brief but extraordinary life was not honoured fittingly by the ‘mean grave’ that held his remains.

Describing the emotions that came over him as he stood by Keats’ graveside, Wilde paid florid homage to his hero: ‘I thought of him as of a Priest of Beauty slain before his time; and the vision of Guido’s St. Sebastian came before my eyes as I saw him at Genoa’. He was moved to compose a poem:

HEU MISERANDE PUER (Later renamed THE GRAVE OF KEATS and included in Poems, 1881)

Rid of the world’s injustice and its pain,

He rests at last beneath God’s veil of blue;

Taken from life while life and love were new

The youngest of the martyrs here is lain,

Fair as Sebastian and as foully slain.

No cypress shades his grave, nor funeral yew,

But red-lipped daisies, violets drenched with dew,

And sleepy poppies, catch the evening rain.

O proudest heart that broke for misery!

O saddest poet that the world hath seen!

O sweetest singer of the English land!

Thy name was writ in water on the sand,

But our tears shall keep thy memory green,

And make it flourish like a Basil-tree.

Ever the self publicist, Wilde sent his poem to the eminent poet, patron and politician Lord Haughton, editor of Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats (1848). Inviting Haughton to comment on his tribute, Wilde also petitioned his support for a campaign to replace an ‘extremely ugly’ bas relief of Keats’ head, which had been erected close to his grave, with something befitting ‘a lovely Sebastian killed by the arrows of a lying and unjust tongue’.

Wilde could be fiercely proprietorial in his devotion; he chose ‘Keats House’ as the name for the Chelsea home he shared with artist Frank Miles and suggested that only those who shared Keats’ genius were worthy of copying his distinctive style. Certainly, his own early work resonates with echoes of his predecessor, a similarity that was apparent to his critics. One anonymous and damning review of Poems, published in The Athenaeum, asserted that Wilde’s derivative style grew ‘out of a misunderstanding worship of Keats’, and concluded ‘in spite of some element of grace and beauty’, his poems had ‘no element of endurance’. This proved to be the case.

Keats was a pioneer of aestheticism: ‘What the imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth’, he declared in a letter to his great friend Benjamin Bailey, written in November 1817. Little wonder Wilde insisted: ‘It is in Keats that one discerns the beginning of the artistic renaissance of England’. Again and again, he invoked his hero as a touchstone for the admirable or the unworthy.

Wilde was scathing in ‘Two Biographies of Keats’, a review piece he wrote for the Pall Mall Gazette in September 1887. While he favoured Sidney Colvin’s evaluation over William Rossetti’s ‘great failure’, he chastised the former for drawing attention to Bailey’s toned-down characterisation of Keats as a man of ‘commonsense and gentleness’, insisting ‘we prefer the real Keats, with his passionate wilfulness, his fantastic moods and his fine inconsistence’.

Although The Athenaeum derided it, the depth of Wilde’s devotion was recognised by Keats’ niece Emma Speed, daughter of his brother George who had moved to America in 1818 and settled in Louisville in 1819. Mrs. Speed, described by Wilde as ‘a lady of middle age, with a sweet gentle manner and a most musical voice’, sought him out after he cited her uncle’s poem ‘Answer to a sonnet by J.H. Reynolds’ during a lecture he delivered at the Masonic Temple in Louisville on Tuesday, 21 February 1882. Wilde accepted her invitation to call on her the following day in order to examine the Keats manuscripts in her possession; he recalled this experience in ‘Keats’ Sonnet on Blue’, an erudite article he wrote for the July 1886 issue of The Century Guild Hobby Horse:

I spent most of the next day with her, reading the letters of Keats to her father, some of which were at that time unpublished, poring over torn yellow leaves and faded scraps of paper, and wondering at the little Dante in which Keats had written those marvellous notes on Milton.

Shortly afterwards, in an act of overwhelming generosity, Emma Speed sent him the original manuscript of ‘Answer to a sonnet by J.H. Reynolds’, prompting him to write in response:

What you have given me is more golden than gold, more precious than any treasure this great country could yield me, though the land be a network of railways, and each city a harbour for the galleys of the world.

It is a sonnet I have loved always, and indeed who but the supreme and perfect artist could have got from a mere colour a motive so full of marvel: and now I am half enamoured of the paper that touched his hand, and the ink that did his bidding, grown fond of the sweet comeliness of his character, for since my boyhood I have loved none better than your marvellous kinsman, that godlike boy, the real Adonis of our age…. In my heaven he walks eternally with Shakespeare and the Greeks…

Three years later, on 2 March 1885, Wilde attended a contentious auction in London at which thirty-five of Keats’s love letters to Fanny Brawne were being sold by her son Herbert Lindon. He expressed his disquiet in ‘On the sale by auction of Keats’s love letters’.

These are the letters which Endymion wrote

To one he loved in secret, and apart.

And now the brawlers of the auction mart

Bargain and bid for each poor blotted note,

Ay! for each separate pulse of passion quote

The merchant’s price. I think they love not art

Who break the crystal of a poet’s heart

That small and sickly eyes may glare and gloat.

Is it not said that many years ago,

In a far Eastern town, some soldiers ran

With torches through the midnight, and began

To wrangle for mean raiment, and to throw

Dice for the garments of a wretched man,

Not knowing the God’s wonder, or His woe?

Yet, despite his apparent distaste, Wilde reportedly spent eighteen pounds on one of these letters. Perhaps he regarded himself as a worthy keeper of the flame. In truth, he was.

October 17, 2015

Wilde’s Women in The Irish Times

My book, Wilde’s Women was officially published yesterday, which was Oscar Wilde’s 161st birthday. It was lovely to have the opportunity to mark the occasion with a feature in The Irish Times. There’s a link to it here and I’ve posted it below:

Oscar Wilde: ladies’ man

Oscar may have been gay but many of the key people in his life were women, says author Eleanor Fitzsimons. He also championed women writers and feminists

“Do you have any other ideas?” With these words my endlessly patient agent ended his explanation of why the book proposal his naive new client had devoted the best part of a year to wasn’t generating sufficient interest among publishers. Sure, they admired my writing style and found my subject compelling but, and I’m paraphrasing here, in the cut-throat world of bookselling, they considered my biography of Harriet Shelley, tragic first wife of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, too niche to take a punt on.

It felt at that moment as if the heady days of securing representation, winning a couple of literary prizes and dreaming of one day holding a book in my hands that had my name on the cover had come to an end. But nobody likes to leave an uncomfortable silence and it seemed impolite, if not downright remiss, to admit to having no more ideas at all. And so it was that I blurted out the words “Wilde” and “women”.

What was I thinking? Why would anyone in their right mind choose to write yet another book about Oscar Wilde? Well, unlike poor Harriet, he is universally renowned. Think about it. Not a single day goes by in this, the country of his birth, and in most other countries, without some broadcaster or columnist channelling Wilde’s wit, some theatre director reprising one of his sharp social comedies, or some aspirant author pitching a book about the minutiae of his life. Why shouldn’t I join them?

Oscar Wilde: elusive ego, extraordinary wit and enduring genius

Oscar Wilde: elusive ego, extraordinary wit and enduring geniusAnyway, I wasn’t really going to write about Oscar Wilde at all. I was going to write about the women in his life. “The women,” you ask. “What women? We thought he was gay.” Well, he was, but he was also a loving husband, a besotted boyfriend, an affectionate brother to his lovely little sister, a devoted son, and a brilliant best friend to some very impressive women. In Aspects of Wilde, Vincent O’Sullivan described his friend’s uncommon fondness for women:

I have always found, and find today, his [Wilde’s] warmest admirers among women. He, in his turn, admired women. I never heard him say anything disparaging about any woman, even when some of them required such treatment!

Even Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s beloved Bosie, admitted: “With women he succeeded a great deal better than with men.”

Ever since I first encountered Lady Jane Wilde, Oscar’s flamboyant mother and an enduring heroine in his native Ireland, I’ve been intrigued by the influence she had on her son’s life and work. Jane was a poet, a revolutionary, a feminist and a lifelong campaigner for better access to education for women. She was also an incorrigible snob and a brilliant conversationalist whose Saturday conversazione and literary Wednesdays were always packed. She never doubted the genius of her sons and her wholehearted support may have made them reckless.

Far too little has been written about Wilde’s first love, Florence Balcombe, who left him for Bram Stoker and fought tenaciously to secure her rights to her husband’s literary estate. Best remembered for her beauty, she was described by writer Horace Wyndham as “a charming woman and brim full of Irish wit and impulsiveness”. Wilde found brief happiness and stability with his wife, Constance, mother to his two beloved sons. Beautiful, accomplished, politically active and hugely supportive of her brilliant husband, she did her best to stand by him until the end of her heartbreakingly short life.

As an individualist, Wilde believed that few limits should be placed on anyone’s life. He chose as some of his closest friends, freethinking women who challenged conventional gender roles and pushed their way into the public sphere, ignoring the tut-tutting of a society determined to keep them down. He traded witticisms with these women, promoted their work, collaborated with them on theatrical productions, dedicated stories to them and drew inspiration from their lives. Several of his most outspoken and memorable characters are women: Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Ernest, Mrs Erlynne in Lady Windermere’s Fan, Mrs Allonby in A Woman of No Importance.

While some of Wilde’s friends, Lillie Langtry, Ellen Terry and Sarah Bernhardt, are household names, he also engendered extraordinary loyalty in women who are largely forgotten: witty and vivacious Ada Leverson, who inspired his sparkling dialogue; and kind-hearted Henrietta Vaughan Stannard, who published bestselling novels as John Strange Winter and invented her own line of cosmetics. When Wilde toured America, society women paved his way. When he edited The Woman’s World, a progressive women’s magazine, he invited contributions from feminist campaigners and leading thinkers on gender.

At Oxford, Wilde dedicated his Newdigate Prize winning poem, Ravenna, to George Fleming, nom de plume of playwright and novelist Julia Constance Fletcher; he admitted that he was “attracted by her in every way”. He gave renowned feminist and pacifist Helena Swanwick her start in journalism and she wrote of him: “His extravaganzas had no end, his invention was inexhaustible, and everything he said was full of joy and energy”.

At the height of his fame, Wilde was welcomed into the most fashionable drawing rooms in London. As O’Sullivan put it:

In the upper reaches of English society it was not the men, who mostly did not like him, who made his success, but the women. He was too far from the familiar type of the men. He did not shoot or hunt or play cards; he had wit, and took the trouble to talk and be entertaining.

Yet many of these women distanced themselves after he was imprisoned and poet Alice Meynell, formerly an admirer, declared “while there is a weak omnibus horse at work or a hungry cat I am not going to spend feeling on Oscar”.

The women in Wilde’s Women are deserving of at least one book each, and in some instances these biographies exist. Their lives are fascinating and fraught with the challenges of operating in an oppressively patriarchal world. By examining them collectively in terms of their relationship to Wilde, I hope to bring them to the attention of a new readership, and to expose a neglected facet of the most-talked-about man in the world.

Wilde’s Women by Eleanor Fitzsimons is published by Duckworth Overlook on October 16th

October 9, 2015

In Search of Wilde’s Women

The window of the brilliant Gutter Bookshop in Dublin, where I’m launching my book

I’m delighted to have a feature article on the wonderful http://www.booksbywomen.org website today. Here’s a link to it or you can read it below:

If you were asked to name a man you would not readily associate with women, Oscar Wilde might spring to mind. Due to the relentless focus on his sexuality and the magnitude of the injustice perpetrated against him, Wilde’s life is often examined in terms of his relationships with men.

Yet, as I discovered when researching my book Wilde’s Women, he had a genuine fondness for women and they in turn were drawn to him. As Vincent O’Sullivan, Wilde’s friend and biographer confirmed in Aspects of Wilde:

I have always found, and find today, his [Wilde’s] warmest admirers among women. He, in his turn, admired women. I never heard him say anything disparaging about any woman, even when some of them required such treatment!

Of course, as the second son of the sharp-witted Lady Jane Wilde, how could Oscar be anything but admiring and supportive of strong women? As Speranza, Oscar’s mother became a celebrity long before her son. A revolutionary poet and essayist, an accomplished translator, and a quixotic campaigner for women’s rights, she also insisted that a loyal wife should accommodate her husband’s indiscretions.

Wilde’s life was not short on tragedy and the first of these was the loss of his beloved sister Isola, probably to meningitis, when he was twelve years old and she was not quite ten. The Wilde family was devastated by this loss. Jane had described her daughter as ‘the radiant angel of our home – and so bright and strong and joyous’ and Oscar treasured a lock of her hair until the day he died.

What of romance? Wilde is a gay icon and appears to have been attracted exclusively to men for much of his life, yet as a young man he was involved with several women. His first girlfriend, the extraordinarily beautiful and vivacious Florence Balcombe, dropped him to marry fellow Dubliner Bram Stoker, author of Dracula. The letters and poems he sent her during their two year courtship demonstrate a depth of feeling that might surprise those who believe his only love was Lord Alfred Douglas.

Aged twenty-nine, Wilde married Constance Lloyd, mother to his beloved sons, Cyril and Vyvyan. Although far less flamboyant than her husband, Constance was highly accomplished, politically active and hugely supportive of him. She was devastated by his infidelity, but did everything she could to help him after his arrest. Wilde loved Constance dearly for a time and he mourned her when she died.

Throughout his life, Wilde promoted progressive women. Most notable perhaps are the two years he spent editingThe Woman’s World, which he transformed into ‘the recognised organ for the expression of women’s opinions on all subjects of literature, art, and modern life’. He commissioned leading thinkers and campaigners on gender and women’s rights to explore topics that included access to education and the professions, and voting rights for women. In his monthly ‘Literary and Other Notes’, he enthused about women writers.

Every play Wilde wrote, from Vera, his very first, to The Importance of Being Earnest, which had the working title Lady Lancing, was named for a woman in early drafts. Most feature iconic women characters: Mrs. Erlynne in Lady Windermere’s Fan, Mrs. Allonby in A Woman of No Importance, Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest.

Every play Wilde wrote, from Vera, his very first, to The Importance of Being Earnest, which had the working title Lady Lancing, was named for a woman in early drafts. Most feature iconic women characters: Mrs. Erlynne in Lady Windermere’s Fan, Mrs. Allonby in A Woman of No Importance, Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest.

Through his social comedies, he exposed the deep-rooted hypocrisy that prevailed in patriarchal Victorian society, reserving his most biting commentary for puritanical women who insisted that the strictures imposed on them be applied equally to men. Wilde’s favourite of his plays, according to his friend Ada Leverson, was Salomé. He dreamed of seeing Sarah Bernhardt play the eponymous princess but, sadly, never did.

An ambitious outsider, Wilde understood the importance of befriending society women who presided over the most fashionable and influential drawing rooms in London and beyond. He cultivated friendships with free-thinking, enterprising and intelligent women like Lillie Langtry, one time mistress of the Prince of Wales, and Ellen Terry, one of the most acclaimed actresses of the day, and he delighted aristocratic women with his stories, which he dedicated to them.

Nowhere was the support of powerful women more important than in America, where dozens of wealthy and influential women who delighted in his compelling personality promoted him with enthusiasm.

Wilde provoked extraordinary loyalty in women who are largely forgotten today: witty author and satirist Ada Leverson, and the extraordinarily generous Adela Schuster, who funded him after he was imprisoned. He collaborated on a poem with Polish actress Helena Modjeska, who had fled political persecution, and funded American actress Elizabeth Robbins when she brought the plays of Ibsen to England and staged them herself. He harnessed the epigrammatic language used by women like the extraordinarily popular but largely forgotten novelist Ouida and his work was often compared to hers.

When his popularity was at its height, Wilde was fêted and adored by women from every walk of life. Yet many of them abandoned him during the few years that remained to him after he was released from prison. Many of the warmest and most revealing accounts of him were written by women who remained loyal to the end. Rather than treating Wilde as a brilliant but broken man who paid the highest price for being who he was, we should remember him as feminist and pacifist Helena Swanwick did: ‘His extravaganzas had no end, his invention was inexhaustible, and everything he said was full of joy and energy’.

—

Eleanor Fitzsimons is a researcher, writer and journalist specialising in historical and current feminist issues. She has an MA in Women, Gender and Society from University College Dublin. In 2013, she won the Keats-Shelley Essay Prize with her essay ‘The Shelleys in Ireland’ and she is a contributor to the Romanticism Blog. Her work has been published in a range of newspapers and journals including The Irish Times, the Guardian, History Ireland andHistory Today. She is a regular radio and television contributor. Her first book, Wilde’s Women will be published by Duckworth Overlook on 16 October 2015.

October 6, 2015

Interview with Sean Moncrieff

Click here for a link to my interview on the Sean Moncrieff Show on Newstalk FM yesterdayabout Wilde’s Women

September 20, 2015

Entering The Woman’s World: Oscar Wilde as Editor of a Woman’s Magazine

I am absolutely delighted to have an article on Oscar Wilde as Editor of The Woman’s World magazine, which is based on a paper I delivered to Communities of Communication II in Edinburgh University, 10-11 September 2015, published on the superb Victorian Web. This is an excellent resource for scholars and anyone with an interest in the period. My article is here and reproduced below:

In April 1887, Oscar Wilde accepted the position as editor of The Lady’s World, a high-end, illustrated monthly magazine produced by Cassell and Company. Wilde expressed the opinion to poet Harriet Hamilton King that The Lady’s World was ‘a very vulgar, trivial, and stupid production’ (Complete letters, 332) and, in the face of strong opposition from Cassells, he renamed the magazine The Woman’s World. In a letter to Thomas Wemyss Reid, General Manager of Cassells, he undertook to transform the magazine into ‘the recognised organ for the expression of women’s opinions on all subjects of literature, art, and modern life’ (Complete letters, 297). He vowed that, under his editorship, The Woman’s World would: ‘take a wider range, as well as a high standpoint, and deal not merely with what women wear, but with what they think, and what they feel’ (297).

A reproduction of the magazine cover, the title-page with Wilde’s name, and the binding of The Woman’s World annual volume. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Wilde’s Motivation

It is often assumed that Wilde took on this editorial role simply to secure access to a regular income. Certainly, as a married man of thirty-two with a young family to provide for and exquisite tastes to gratify, he found it impossible to fund the lifestyle he desired out of his unreliable earnings as a freelance reviewer and, by then, occasional lecturer. Although his wife Constance brought a modest allowance to the household, by 1887 the couple’s resources were falling distressingly short of their outgoings and they were looking for tenants for their lovely Tite Street home. Yet, although the weekly salary of six pounds was very welcome, it does not account entirely for Wilde’s motivation in agreeing to accept Cassell’s offer.

As a committed individualist, Wilde believed that women should be allowed far more autonomy than they were afforded by patriarchal Victorian society. He also shared his mother’s opposition to gendered writing, resistance she had expressed in forthright terms when, as a young woman, she had been offered control of the ‘woman’s page’ of The Nation newspaper. Echoing his mother’s distain, Wilde quipped in a letter to Wemyss Reid: ‘artists have sex but art has none’ (Complete letters, 298).

As a regular contributor to several popular periodicals, Wilde must have realised how badly served intelligent, ambitious women were by the plethora of new magazines claiming to represent their interests. In response, he used The Woman’s World to point out the more absurd aspects of gender discrimination, and to facilitate debate on the contentious issues faced by women who were attempting to enter the public sphere. He also offered a platform to emerging women writers who displayed a style that could be considered more edgy than that adopted by their peers.

Wilde’s zeal for his new role was palpable: ‘I am resolved to throw myself into this thing,’ he told Wemyss Reid, ‘I grow very enthusiastic over our scheme’ (Complete letters, 299-300). In ‘Oscar Wilde as Editor’, an article he wrote forHarper’s Weekly in 1913, Arthur Fish, the young man appointed by Cassell and Company as Wilde’s sub-edito, insisted that the ‘keynote’ of The Woman’s World under Wilde’s editorship was no less than ‘the right of woman to equality of treatment with man’ (Fish, 18). Fish also testified that several of the articles on ‘women’s work and their position in politics were far in advance of the thought of the day’ (18).

Contributors

With the help of his well-connected friend Lady Mary Jeune, Wilde compiled a list of potential contributors, among them prominent social activists, literary luminaries and society women, including two princesses. Fish called them ‘a brilliant company of contributors which included the leaders of feminine thought and influence in every branch of work’ (18). Since Wilde had told Wemyss Reid that he intended to make The Woman’s World ‘a magazine that men could read with pleasure, and consider it a privilege to contribute to’ (Complete letters, 297), he also invited several men to submit articles.

The first issue of The Woman’s World appeared in November 1887. A fresh cover design featured Wilde’s name prominently with key contributors listed below. In a significant departure from convention, each article was attributed to its author by name. Wilde also increased the page count from thirty-six to forty-eight, and relegated fashion to the back while promoting literature, art, travel and social studies. Gone entirely were ‘Fashionable Marriages’, ‘Society Pleasures’, ‘Pastimes for Ladies’ and ‘Five o’clock Tea’. In his ‘Literary and Other Notes’, Wilde demonstrated unequivocal support for the greater participation of women in public life. He campaigned for them to be granted access to education and the professions, and argued that the ‘cultivation of separate sorts of virtues and separate ideals of duty in men and women has led to the whole social fabric being weaker and unhealthier than it need be’ (WW, 2 (1897): 390).

The editorial direction Wilde intended to take was signalled by the inclusion in the very first issue of ‘The Position of Women’, a lengthy article from Eveline, Countess of Portsmouth. She welcomed amendments to marriage law designed to reform an institution that, in her view, ‘might and did very often represent to a wife a hopeless and bitter slavery’ (WW, I, 8). In ‘The Fallacy of the Superiority of Man’, published the following month, Laura McLaren, founder of the Liberal Women’s Suffrage Union, asked: ‘If women are inferior in any point, let the world hear the evidence on which they are to be condemned’ (WW, I, 54).

A New Slant on Fashion

Left: Scene from “The Faithful Shepherdess” — the frontispiece to the 1888 Woman’s World. Right: Orlando. Both plates are illustrations to “The Woodland Gods” by Janey Sevilla Campbell. These images and those below coem from the Internet Archive version of a volume in the Stanford University Library. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Although fashion remained a key feature, a conventional round-up of the season’s trends was supplemented with articles on cross-dressing, aesthetic design and rational dress. On the first page of his first edition, Oscar published ‘The Woodland Gods’ a review by the aristocratic Janey Sevilla Campbell, more commonly known as Lady Archibald Campbell, of three cross-dressing dramas staged by her Pastoral Players at her home, Coombe House in Surrey. This article was illustrated with images of Janey dressed as a young man to play Orlando in As You Like It and embracing a woman as Perigot in Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess.

Examples of the large number of conventional illustrations of current fashion, which appeared every month — these from Mrs. Johnstone’s “November fashions.” Left: Morning Costume and Frock with Velvet Yoke — Right: Winter Mantles and Mantlets. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In ‘The Pictures of Sappho’, in April 1888, classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison challenged several gender-based conventions while, in June 1889, ethnographer Richard Heath contributed an article titled ‘Politics in Dress’. A feature on fans as a feminine symbol pointed out that they were originally carried by men as a sign of power, while one on gloves asked why men, once such decorative dressers, had become so ‘sober’. In ‘Women Wearers of Men’s Clothes’, published in January 1889, Irish-born journalist Emily Crawford insisted that women who adopted masculine styles could accomplish ‘heroic duties’, while novelist Ella Hepworth Dixon applauded the ‘semi-masculine and completely appropriate gear’ adopted by women who rode.

Wilde joined the debate in his very first ‘Literary and Other Notes’ by declaring that, in time, ‘dress of the two sexes will be assimilated, as similarity of costume always follows similarity of pursuits’ (WW, I, 40). He also castigated the ‘absolute unsuitability of ordinary feminine attire to any sort of handicraft, or even to any occupation which necessitates a daily walk to business and back again in all kinds of weather’ (I, 40). In his opinion, restrictive clothing prevented women from taking their rightful place alongside men. Insisting that ‘the health of a nation depends very much on its mode of dress’, Wilde described how ‘from the Sixteenth Century to our own day there is hardly any form of torture that has not been inflicted on girls and endured by women, in obedience to the dictates of an unreasonable and monstrous Fashion’ (I, 40).

Education and Employment

Education too was a key focus of The Woman’s World. In January 1888, in his review of Women and Work, a collection of essays by poet and philanthropist Emily Jane Pfeiffer, Wilde quoted Daniel Defoe, who had asked ‘what has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught!’ (WW, I, 135-56) He commissioned articles on the women’s colleges and on Alexandra College in Dublin, an all-girls institution of higher education. He also published a series of articles encouraging those few, fortunate women who had benefitted from access to higher education to explore opportunities opening up to them in the professions.

Several articles in The Woman’s World drew attention to the blight of poverty that afflicted women and their children. In several instances, the authors of these articles proposed solutions that went far beyond the usual ineffectual charitable works. In ‘Something About Needlewomen’, published in May 1888, trade unionist Clementina Black, who had helped establish the Woman’s Trade Union Association, highlighted the plight of impoverished needlewomen who were unable to earn a living wage from the piecework they were given. She encouraged them to combine into cooperatives. In July 1888, in one of several features dealing with Irishwomen, Irish journalist Charlotte O’Connor Eccles drew attention to the alarming conditions endured by Dublin’s women weavers, and insisted that their poverty should be alleviated through education and training. Emily Faithfull, a member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, wrote of the duty of teaching girls some trade, calling or profession.

It is interesting that many of these themes found their way into Wilde’s stories, most notably ‘The Happy Prince’ and ‘The Young King’. His inclusion of the impoverished match-girl in the former must surely represent a nod to the fourteen-hundred women and girls who had gone on strike at the Bryant and May match factory in 1888, refusing to work until their appalling conditions and inadequate wages were improved.

Woman and Politics

Wilde tackled the contentious issue of politics head-on and was unequivocal in his support for the greater participation of women. Reviewing David Ritchie’s Darwinism and Politics in May 1889, he praised that author’s rebuttal of Herbert Spencer’s contention that, should women be admitted to political life, they might do mischief by introducing the ethics of the family into affairs of state: ‘If something is right in a family,’ Wilde countered, ‘it is difficult to see why it is, therefore, without any further reason, wrong in the state’ (WW, II, 390). He commissioned articles on the campaign for women’s suffrage and he helped Lady Margaret Sandhurst in her controversial bid to be elected to the London City Council by publishing in full a speech she had delivered.

Literature

Naturally, literature was a key focus of The Woman’s World. One of Wilde’s most rewarding tasks was the commissioning of new works of fiction from emerging and established women writers. The best article in the December 1887 issue, he told poet Louise Chandler Moulton, would be ‘a story, one page long, by Amy Levy . . . a mere girl, but a girl of genius’ (Moulton, 123). Levy had sent the story unsolicited. In response, Wilde commissioned a second story, two poems and two articles. He also championed South-African-born radical feminist Olive Schreiner who, agitated for greater access to political life and an end to the sexual double standard.

In ‘Literary and Other Notes’, Wilde gave what he called ‘special prominence’ to books written by women. The aesthetic and new woman writers he promoted included E. Nesbit, who he described as ‘a very pure and perfect artist’ (WW, I, 36); and controversial poet Rosamund Marriot Watson, who wrote as Graham R. Tomson. When Tomson became editor of aesthetic magazine Sylvia’s Journal in 1893, it was clear that she had learned much from her association with The Woman’s World.

Reaction to The Woman’s World

So what was the reaction to The Woman’s World under Wilde’s stewardship? In Oscar Wilde and his Mother, published in 1911, Wilde’s friend Anna de Brémont declared, ‘[S]ociety began to take Oscar Wilde seriously when he became editor of The Woman’s World’ (73). She described how the magazine caused a ‘flutter in the boudoirs of Mayfair and Belgravia’. Certainly, Constance and Lady Wilde’s drawing rooms were thronged with would-be contributors. The press response was similarly positive: ‘Mr Oscar Wilde has triumphed,’ declared the Nottingham Evening Post, ‘the first number of the “Woman’s World” has already appeared, and has, I believe, been sold out’. Praising Wilde for ‘striking an original line’, the Times hailed The Woman’s World as ‘gracefully got up…in every respect’.

Rival publication Queen admired the improved appearance and impressive array of contributors. The assessment of the St James’ Gazette must have delighted Wilde. ‘The Women’s World is a capital magazine for a married man to buy,’ its reviewer declared. ‘He tells his wife he got it entirely for her sake; but he may always find some very good reading for himself.’ The Spectator decided: ‘The change is undoubtedly one for the better, in the sense of the higher’. Describing the articles as ‘extremely bright and useful’, the Irish Times recorded how, on the evening of the launch, ‘[T]here was not one in the West End to be had for love or money and impatient people could only get through the interval between Saturday and Monday by borrowing copied from friends. Perhaps the most significant reaction of all came from The Englishwoman’s Review, the organ of the suffragist movement in Britain. While refraining from praising The Woman’s World overtly, it ran notices attracting the attention of readers to more progressive articles.

Disillusionment

Under the terms of his contract, Wilde had agreed to spend two mornings a week in the offices of Cassell & Company. After a while, Arthur Fish could tell ‘by the sound of his approach along the resounding corridor whether the necessary work to be done would be met cheerfully or postponed to a more congenial period’. On a good day, there would be ‘a smiling entrance, letters would be answered with epigrammatic brightness, there would be a cheery interval of talk when the work was accomplished, and the dull room would brighten under the influence of his great personality’ (18).

Fish never doubted Wilde’s commitment to The Woman’s World and he described how hard his boss fought to retain editorial control:

Sir Wemyss Reid, then General Manager of Cassell’s, or John Williams the Chief Editor, would call in at our room and discuss them [issues] with Oscar Wilde, who would always express his entire sympathy with the views of the writers and reveal a liberality of thought with regard to the political aspirations of women that was undoubtedly sincere.

Yet, Wilde’s tenure was short-lived. Much of his disenchantment was born of frustration rather than a lack of commitment: ‘I am not allowed as free a hand as I would like’ (Complete letters, 325), he told his friend Helena Sickert in October 1887. In a letter to Scottish writer William Sharp, he complained: ‘The work of reconstruction was very difficult as the Lady’s World was a most vulgar trivial production, and the doctrine of heredity holds good in literature as in life’(Complete letters, 332).

As early as December 1887, Cassells were objecting to the ‘too literary tendencies’ (Complete letters, 337) of The Woman’s World. In October 1888, Oscar asked the board to authorise the purchase of a story from Frances Hodgson Burnett, but her name never appeared. Nor did four illustrated articles he had hoped to commission from French explorer and archaeologist Madame Jeanne Dieulafoy. Wilde’s despondence deepened when Cassell’s refused to drop the price to sixpence or seven pence in order to attract a wider readership. Fish noticed that his interest was waning: ‘After a few months,’ he remembered, ‘his arrival became later and his departure earlier until at times his visit was little more than a call’. Wilde’s ‘Literary and Other Notes’ disappeared after the fourth issue and, although it was reinstated at Cassell’s instance, he began to miss his deadlines. It may sound trivial but one of the toughest challenges Wilde faced was Cassell’s strict no smoking policy.

Fish had once described his boss as ‘Pegasus in harness’ and now he was pulling at the reigns. A typical day towards the end of his tenure went as follows: ‘He would sink with a sigh into his chair, carelessly glance at his letters, give a perfunctory look at proofs or make-up, ask “Is it necessary to settle anything to-day?” put on his hat, and, with a sad “Good-morning”, depart again’ (The House of Cassell, 134). In April 1889, Wilde informed the Board of Inland Revenue that he would be leaving Cassell & Co. in August. His final ‘Literary and Other Notes’ appeared in June 1889, and by October his name was gone from the cover.

After Wilde’s departure, The Woman’s World reverted to its unadventurous roots. A renewed focus on fashion prompted The Woman’s Penny Paper to scold: ‘To dress is surely not considered the first or the only duty of women, even by their greatest enemies’. The magazine was discontinued shortly afterwards. Wilde had not neglected his own work during his two-year tenure as editor. Dozens of his poems, reviews, essays and stories were accepted by various periodicals during this time and he also published and promoted his first collection of stories, The Happy Prince and Other Tales. The break with Cassells heralded an exceptionally productive period that saw the publication of two further collections of short stories: Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime and Other Stories, and The House of Pomegranates; a collection of essays called Intentions; and The Picture of Dorian Gray, his only novel. While Wilde’s sincerity and sympathy were never in doubt, his interest in coping with the day-to-day challenges of bringing out a magazine on someone else’s behalf certainly was.

References

Chandler Moulton, Louise. The Literary World: a Monthly Review of Current Literature 20.8 (1889): 123-27.

De Brémont, Anna. Oscar Wilde and His Mother: A Memoir. London: Everett & Co. 1911.

Fish, Arthur (A). ‘Oscar Wilde as Editor’ Harper’s Weekly. 58 (1913): 18-20.

Anon. The Story of the House of Cassell. London: Cassell & Co, 1922. 114-46.

Wilde, Oscar, The Complete letters of Oscar Wilde. Eds. Holland, Merlin and Rupert Hart-Davis. London: Fourth Estate, 2000.

Wilde, Oscar (Ed), The Woman’s World. 2 vols. London: Cassell & Company, 1888.

August 18, 2015

Coming Soon….

The reason for neglecting my blog will hit the shops on 16 October 2015, the 161st anniversary of Oscar Wilde’s birth. I’ll be adding a lot of Wilde related posts soon!

April 27, 2014

HARRIET SHELLEY

Harriet Shelley’s engagement ring

I was delighted to be asked to write a post for the excellent new Romanticism Blog, hosted on the http://www.wordsworth.org.uk site. My contribution concerns the short and tragic life of Harriet Shelley, first wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and is reproduced below. It can also be found on the Wordsworth Trust Blog here:

On Thursday, December 12, 1816, a short but intriguing report was carried on page two of The London Times. It read:

“On Tuesday a respectable female, far advanced in pregnancy, was taken out of the Serpentine River and brought to her residence in Queen Street, Brompton, having been missed for nearly six weeks. She had a valuable ring on her finger. A want of honour in her own conduct is supposed to have led to this fatal catastrophe, her husband being abroad”.

Five days earlier, on the evening of Saturday, December 7, 1816, the day that was almost certainly her last, Harriet Shelley, aged twenty-one, wrote a rambling letter filled with self-recrimination. Sometime later, she walked the short distance to Hyde Park and entered the icy waters of the Serpentine. At the time of her death, Harriet had lived apart from her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley – father to their two young children – for more than two years, and the child she carried was almost certainly not his.

During the inquest that was held the following day in the nearby Fox Alehouse, Harriet’s identity and the grim details of her lonely death were obscured, although coroner, John Gell did attempt to close off speculation that she might have been murdered by releasing a statement confirming: ‘The said Harriet Smith had no marks of violence appearing on her body, but how or by what means she became dead, no evidence thereof does appear to the jurors’. An inconclusive verdict of, ‘Found dead in the Serpentine River’ was returned and no mention was made of her obvious pregnancy. She was buried as ‘Harriett Smith’.

Almost six years earlier, on the bitterly cold January day when she first met eighteen-year-old Percy Bysshe Shelley, Harriet Westbrook had been a strikingly pretty, fifteen-year-old pupil at Mrs. Fenning’s boarding school in Clapham; he was brother to two of her schoolmates, Mary and Hellen. Although the fiery young poet unsettled her with his radical notions of atheism, it was to him she turned, after just six months of friendship, when her father was insisting that she remain on at school even though, at sixteen, she would be older than any other girl there.

Although Shelley was keen to help Harriet, he had absolutely no intention of proposing marriage, and assured his good friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg, ‘if I know anything about love, I am NOT in love’. His rash suggestion that they elope to Edinburgh was prompted by a letter from Harriet containing a credible threat of suicide; later, he confided in his friend Elizabeth Hitchiner that, ‘suicide was with her a favourite theme’. After they were married under Scots Law on August 29, 1811, Harriet and Shelley spent three chaotic years criss-crossing England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland in pursuit of his ill-fated notions of social revolution and communal utopia. As their disapproving families had cut off all funds, they struggled to stay out of reach of their creditors.

On 23 June, 1813, Harriet gave birth to a daughter, Eliza Ianthe, known always by her middle name. Parenthood brought fresh anxieties, and their chaotic finances, compounded by Harriet’s reluctance to breastfeed, fuelled fierce arguments. By Christmas, they were spending long periods of time apart. Ironically, it was during this turbulent period that the couple remarried under English law in an attempt to regularise the legality of their relationship. They must have maintained some degree of cordiality, as Harriet became pregnant with their second child that same month. Nevertheless, the marriage was effectively over, and Shelley told Hogg that he, ‘felt as if a dead and living body had been linked together in loathsome and horrible communion’.

The final blow was delivered when Shelley became besotted with sixteen-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. He fled abroad with her, and implored his wife to support this new relationship. He even invited her to join them in Switzerland. Harriet was distraught. She returned to her father’s house and gave birth to baby Charles. For two years, she led a life of quiet desperation, pestered for money by her errant husband and deprived of her infant children, who were sent to the countryside for their health. By spring, 1816, although she engaged little with society, Harriet was pregnant for a third time. The names of several candidates have emerged over the years, but the identity of the father has never been established.

In the decades that followed her death, Harriet Shelley was viciously slandered by supporters of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and strenuous attempts were made to erase all trace of her from Shelley’s life. The notion that Shelley had been tricked into marriage gained currency among those who regarded her as an unequal partner for him. Yet her supporters defended her staunchly, and perhaps the most vehement, though least likely of these was Mark Twain in his persuasive essay, In Defense of Harriet Shelley.

By mining the archives, we can uncover a clear sense of Harriet’s character, and her significance. She was beautiful, clever, witty and kind; fluent in French and competent in Latin; fascinated by history and au fait with current affairs. Yet as a woman of her time, she was afforded no outlet for these accomplishments. There are many recorded instances of her laughing with her husband and teasing him playfully. Yet she was prone to debilitating bouts of depression and, in her blackest moods, contemplated suicide.

The stability that Harriet offered Shelley during their short marriage allowed him to push the boundaries and develop the strong political sensibilities that characterise his work. Although life with him was chaotic, she was unwavering in her support: she accompanied him to Ireland to preach revolution; facilitated his attempts to establish a utopian commune; cared for him when he seemed utterly demented; and bore him children, one of whom would continue his line. The novelist and poet Thomas Love Peacock, who was a good friend to both, described how Harriet, ‘accommodated herself in every way to his tastes. If they mixed in society, she adorned it; if they lived in retirement, she was satisfied; if they travelled, she enjoyed the change of scene.’

Harriet inspired Shelley’s early poems and haunted his later work. He dedicated his masterful, Queen Mab to her, writing: ‘Thou wert the inspiration of my song’. He was haunted by the part he played in her dreadful, lonely death, and confessed to Byron, ‘I know not how I have survived’. His friend and fellow writer Leigh Hunt believed that it: ‘tore his being to pieces’. Perhaps the best testament to Harriet’s lasting influence is the fact that Shelley countered enquiries about the frequent low moods that blighted the remainder of his short life with the words, ‘I was thinking of Harriet’.

Eleanor Fitzsimons is a freelance journalist and researcher. Her work has appeared in publications including, The Irish Times,The Sunday Times, History Ireland and The Guardian, and she has researched documentaries for the Irish national broadcaster, RTÉ. She has an MA in Women, Gender and Society from University College Dublin. In 2013, she won the Keats-Shelley Prize and was runner-up for the Biographers’ Club Tony Lothian Prize with ‘A Want of Honour’, her proposed biography of Harriet Shelley. She is represented by the Andrew Lownie Literary Agency.

March 28, 2014

Virginia & I

Virginia Woolf died on this day (28 March) in 1941. Here’s a piece I wrote about her time (& mine) in Richmond, Surrey. It came second in the Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain writing competition and is featured on the Rate My Words Website:

VIRGINIA & I

Paradise Road. Who could resist? Intuition steers me along this perfectly pleasant street, which, inevitably, falls far short of its designation. Yet there are always gems that glitter in the midst of the mundane, and I am drawn by the kingfisher flash of a blue plaque affixed to the wall of number thirty-four. It reads:

‘In this house, LEONARD and VIRGINIA WOOLF lived, 1915-1924, and founded the Hogarth Press, 1917’

In October, 1914, two years into their marriage, Leonard and Virginia Woolf decamped to Richmond-upon-Thames, a tranquil town that spills down the side of a steep hill until its sprawl is halted by the encircling river. Virginia, aged thirty-two, was particularly fragile having barely survived a bout of melancholia brought on by the stress of completing her first novel, The Voyage Out. Leonard hoped that a fresh start at a safe distance would save her from the destructive whirl of bohemianism.

How extraordinary. I am thirty-two, and I too have just arrived in Richmond with my husband of four years, rucksacks on our backs and buzzing with excitement. It is our first visit, but fired up with the daring that accompanies relative youth, we decide to live here with the ease that one might chose between having a coffee in a Costa or a Starbucks. We start a new chapter, eighty-four years almost to the moment after Leonard and Virginia arrived in our new home town.

We are daring, but not foolish. We want to get the measure of the place before anchoring ourselves too firmly, and look for signs that read ‘to let’ and not ‘for sale’. Virginia was wary too. Although it had nearly done for her, she missed the maelstrom of Bloomsbury life and feared that she would soon tire of the tranquility prescribed by Leonard. They took lodgings at 17, The Green, a lovely Georgian townhouse with a distinctive Dutch gable that lifts it above its neighbours. We walk past it on our way to The Cricketers, seven doors down. Our temporary home is close by: a modest apartment located eighty-four years and five minutes’ walk away in a starter development that overlooks the District line, the link that kept Virginia plugged into the hedonism of London.

Virginia loved to walk; she spent happy hours exploring the contained beauty of Kew Gardens or the rugged antiquity of Richmond Park, or strolling along the tree-lined banks of the Thames as it unwound around these vast green spaces. As winter closed in, the couple sank into the comfort of their first floor drawing room, and read companionably as the soothing pops and hisses of a roaring fire filled their silence. At breakfast, their Belgian landlady, Mrs. Le Grys – who Leonard described as, ‘an extremely nice, plump, excitable flibbertigibbet, about 35 to 40’ – would chat through the menu for the day with a much recovered Virginia.

On January 25, 1915, the day she turned thirty-three, Virginia agreed to three things: to take a lease on Hogarth House, to buy a printing press, and to acquire, ‘a bulldog, probably called John’. We stay too, and buy an airy, inter-war apartment on the very same road, after it has morphed from Paradise to Sheen. Their new home was the right-hand side of a divided Georgian country house; from her attic window, Virginia could see the pagoda in Kew Gardens. Two tumultuous years passed before the printing press arrived, but ‘John’ remained notional.

The move did not go smoothly. Theirs that is, ours is fine. Virginia fell dreadfully ill, and was hospitalised when her errant mind took to conjuring up terrifying hallucinations. In April, she moved to Hogarth House, accompanied by four private nurses, two by day and two by night. She lay in bed, ‘listening to the voices of the dead’ or watching the sunlight, ‘quiver like gold water on the wall’. At times she was demented, lashing out and babbling incoherently.

Wartime air raids terrorised Richmond two decades before our block was built – the Belgian munitions works in Clevedon Road providing an attractive target. Leonard and Virginia retreated to their cellar, where they perched uncomfortably on wooden boxes, clutching torches in unsteady hands as they listened to the whine of the sirens, the screech of falling bombs, and the ‘at-at’ response of anti-aircraft fire. Virginia recorded it all in her diary.

We are spared the horror of aerial bombardment, but live through a national crisis. England is riddled with foot and mouth disease, and towering pyres dominate news broadcasts. Disinfectant-infused mats litter doorways and pavements, and Richmond Park closes in an attempt to protect the herds of red and fallow deer that have roamed freely since 1529. Peace returned, and Virginia recorded the drunken celebrations in her diary. Her words soar like the fireworks that exploded over the Thames: ‘Red and green and yellow and blue balls rose slowly in the air burst, flowered into an oval of light, which dropped into minute grains and expired.’

We commute to conventional jobs, caught up in the swarm that abandons Richmond every working day, but Leonard and Virginia remained at home. They took delivery of a small hand press and an assortment of old typeface, and learned their new trade from a sixteen-page pamphlet. A congenital tremor in Leonard’s hands – a minor inconvenience that kept him safe from a war that killed one of his brothers and left another badly injured -made it impossible to set type, so he ran the press machines instead. Virginia knelt on the drawing room floor, laboriously setting each line, letter-by-letter, word-by-word, and soon discovered that sorting out print was, ‘the work of ages, especially when you mix the h’s with the n’s, as I did yesterday’. Yet it was: ‘exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying’.

Satisfying too was the editorial freedom that allowed the Hogarth Press to print only those books that, ‘the commercial publisher would not look at’. As Two Stories – their first publication, which contained: ‘The Mark on the Wall’ by Virginia Woolf, and, ‘Three Jews’ by Leonard Woolf – rolled off the presses, they saw that the ink had adhered unevenly– thick in places and lacking in others. A failure to proofread allowed a plethora of misspellings and poor punctuation to slip through, but the title page bore the imprint ‘Hogarth Press, Richmond 1917’, and a brand new publishing house was born.

During the seven years that the Hogarth Press operated out of Richmond, sixteen of the thirty-two books published were printed by Leonard and Virginia. These included Kew Gardens, Virginia’s delightfully vibrant evocation of one of her favourite local haunts. The Bloomsbury set provided plenty of material, and the couple turned work away, rejecting T.S. Elliot’s suggestion that they publish Ulysses by a young Dubliner named Joyce. Early success allowed them to buy the building, reuniting its divided halves.

The fleeting contentment that Virginia found in Richmond evaporated; in 1923, she confessed: ‘I sit down baffled and depressed to face a life spent, mute and mitigated in the suburbs’. They relocated to lovely, lively Bloomsbury, and there she enjoyed a period of intense creativity, but war returned and their Mecklenburgh Square flat was destroyed in the Blitz. Virginia was floored, and felt too jaded to re-enter the fray. On March 28, 1941, she left her Sussex home, filled her pockets with stones and walked into the River Ouse. She left behind a last love letter to Leonard, thanking him for, ‘the greatest possible happiness’.

On January 23, 2001, two days short of Virginia’s birthday, I give birth to a tiny, perfect baby boy. I love my London child, but parenthood triggers my own descent into despair. I have never felt as lost and lonely as I do during those days when I push a pram along streets that once held so much joy. Brought low by isolation, and long, empty days spent in the company of a newborn, I spiral down, gripped by debilitating panic attacks that trick me into believing that I am dying and that no-one else will care for my son.

This, despite the fact that my capable and loving husband, who takes over at night and on week-ends, is a twenty-minute train ride away and constantly at the end of a phone line; anxiety cannot easily be rationalised away. I leave Richmond, no longer able to trust myself to be alone with my little one. I close the door on our lovely garden flat, and walk past Leonard and Virginia’s old home on my way to the train station. I will never live here again.

I feel so connected to Virginia. She looms large and I am minute in her shadow, yet I have shared her suburban existence. I would treasure a tiny measure of her brilliance – she burned so very brightly – but I will settle for the modesty of my own talent as long as I can keep hold of the equilibrium that returned to me but eluded her so cruelly.